Abstract

Colonoscopy is the principal investigative procedure for colorectal neoplasms because it can detect and remove most precancerous lesions. The effectiveness of colonoscopy depends on the quality of the examination. Bowel preparation is an essential part of high-quality colonoscopies because only an optimal colonic cleansing allows the colonoscopist to clearly view the entire colonic mucosa and to identify any polyps or other lesions. Suboptimal bowel preparation not only prolongs the overall procedure time, decreases the cecal intubation rate, and increases the costs associated with colonoscopy but also increases the risk of missing polyps or adenomas during the colonoscopy. Therefore, a repeat examination or a shorter colonoscopy follow-up interval may be suitable strategies for a patient with suboptimal bowel preparation.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Colorectal neoplasm, Bower preparation, Quality

Core tip: Bowel preparation is one of the most frequent reasons why patients object to participating in screening colonoscopies, and inadequate preparation is a major obstacle to achieving a high-quality colonoscopy. Furthermore, the two most important quality indicators of colonoscopy, the adenoma detection rate and cecal intubation rate, are associated with the quality of bowel preparation. Therefore, bowel preparation is critical for high-quality colonoscopies because only optimal colonic cleansing allows the colonoscopist to view clearly the entire colonic mucosa. A greater awareness of the importance of adequate preparation will lead to the improved quality of colonoscopies.

INTRODUCTION

In 2008, the worldwide estimate of the number of new cases of colorectal cancer was 1233000, with an estimated mortality of 608700[1]. Colonoscopy is currently considered the gold standard diagnostic method for colonic disease and the most effective procedure to screen for colorectal cancer (CRC)[2] for the following reasons: (1) colonoscopy can detect and remove all suspicious colorectal lesions; and (2) if any of the other three recommended screening tests (fecal occult blood test, flexible sigmoidoscopy and double contrast barium enema) are positive, they must be followed by a diagnostic colonoscopy[3,4]. However, approximately 3% to 6% of colorectal cancers are diagnosed between the screening and post-screening surveillance examinations[5-7], and the majority of these interval cancers are believed to originate from missed lesions that were overlooked during the screening colonoscopy[8,9]. According to emerging evidence, the effectiveness of a colonoscopy depends on the quality of the examination[10-12]. Bowel preparation is an essential part of a high-quality colonoscopy because only optimal colonic cleansing allows the colonoscopist to clearly view the entire colonic mucosa (from the anal verge to the ileocecal valve) and to identify any polyps or other lesions. Even small amounts of residual stool could prevent the visualization of clinically important lesions. However, reports show that bowel preparation is inadequate in up to 25% of patients undergoing a colonoscopy[13,14]. It is clear that poor preparation prolongs the overall procedure time, decreases the cecal intubation rates, reduces the detection of colorectal neoplasms and increases the costs associated with colonoscopy.

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines include quality indicators to measure the performance of colonoscopies[10,11]. A number of factors were selected to establish competence in the performance of a colonoscopy and to help define areas for continuous quality improvement. The factors that can be affected by the quality of bowel preparation include (1) cecal intubation, which should be achieved in 90% of all cases and in 95% of screening procedures performed on healthy adults; (2) photo documentation of the cecum and its landmarks (the appendiceal orifice, cecal strap, ileocecal valve); and (3) adenoma detection, that is, adenomas, should be detected by a screening colonoscopy in 25% and 15% of healthy men and women, respectively, who are aged 50 years or older (Table 1). In addition, the ASGE-ACG Task Force recommends that the quality of the bowel preparation should be documented in the procedure report. Currently, there is no standardized system to describe the bowel preparation. The US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer suggests the use of the terms, ‘‘adequate’’ or ‘‘inadequate”; an adequate examination is one that allows for the detection of mass lesions other than small (5 mm) polyps, which are generally not obscured by the preparation[15]. Many clinical studies have used the terms ‘‘excellent’’, ‘‘good”, ‘‘fair’’ and ‘‘poor’’ to rate the quality of bowel preparation[16]. ‘‘Excellent’’ is typically defined as no or minimal solid stool and only small amounts of clear fluid that require suctioning. ‘‘Good’’ is typically used to describe no or minimal solid stool with large amounts of clear fluid that require suctioning. ‘‘Fair’’ generally refers to collections of semisolid debris that are cleared with difficulty. ‘‘Poor’’ generally refers to solid or semisolid debris that cannot be cleared effectively (Figure 1)[16].

Table 1.

Quality indicators that can be impacted by bowel preparation in colonoscopy

| Indicator | Definition | Acceptable level |

| Bowel preparation | Proportion of procedures in which colon cleansing is considered excellent or good | > 90% |

| Adenoma detection rate | Proportion of colonoscopies performed in asymptomatic individuals over 50 in which at least one adenoma has been detected | > 20% |

| (men > 25% and women > 15%) | ||

| Withdrawal time | Mean time from cecal intubation to colonoscopy extraction through the anus | > 6 min |

| Cecal intubation rate | Proportion of procedures in which cecal intubation is achieved | > 95% |

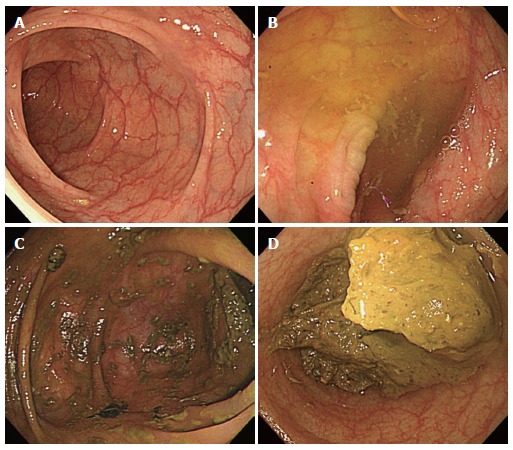

Figure 1.

Representative endoscopic image according to the bowel preparation scale. A: Excellent, there are no or minimal solid stool and only small amount of clear fluid that require suctioning; B: Good, it is used to describe no or minimal solid stool with large amounts of clear fluid that require suctioning; C: Fair, it means the presence of semisolid debris that are cleared with difficulty; D: Poor, it is impossible to observe the colonic mucosa because of solid or semisolid stools.

BOWEL PREPARATION AND COLONOSCOPY EFFICIENCY

The quality of bowel preparation is an important determinant of procedural success. A prospective study of 9223 colonoscopies performed in the United Kingdom that was published in 2004 found that one in five incomplete colonoscopies (failures) was caused by poor bowel preparation[17]. A prospective study of 693 consecutive outpatient colonoscopies identified poor bowel preparation as a significant predictor of prolonged cecal intubation time (≥ 20 min, P = 0.0077)[18]. A prospective study of 909 patients undergoing colonoscopy performed by a single endoscopist reported that an inadequate bowel preparation (fair or poor vs good) was a significantly predicted by a prolonged (≥ 10 min) insertion time [OR = 2.80, 95%CI: 1.41-5.56, P = 0.003][19]. Similarly, another prospective, multicenter study of screening colonoscopy, performed in 3196 individuals aged from 50 to 75 years, reported that a poor-quality bowel preparation was the only variable significantly related to incomplete colonoscopy. Procedural failure rates were significantly higher in patients with poor-quality cleansing (19%) than in patients with an adequate bowel preparation (2%, P = 0.001)[20]. In a retrospective review of 5477 colonoscopies performed by 10 gastroenterologists at a university hospital, Aslinia et al[21] reported that inadequate bowel preparation was a significant predictor of the inability to reach the cecal base (OR = 0.15, 95%CI: 0.12-0.18, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of studies demonstrates an association between bowel preparation and procedural success

| Study | Subjects (n) | Perspective | Outcomes | Results |

| Bowles et al[17] | 9223 | Prospective | Cecal intubation rate | Poor bowel preparation (19.6%) |

| Bernstein et al[18] | 693 | Prospective | Predictor of cecal intubation time (≥ 20 min) | Poor bowel preparation (P = 0.0077) |

| Kim et al[19] | 909 | Prospective | Prolonged insertion time (> 10 min) | Inadequate bowel cleaning |

| (OR = 2.8, 95%CI: 1.41-5.56, P = 0.003) | ||||

| Nelson et al[20] | 3196 | Prospective | Predictor of incomplete colonoscopy | Poor bowel preparation |

| (failure rate = 19.3%, P = 0.001) | ||||

| Aslinia et al[21] | 5477 | Retrospective | Cecal intubation rate | Inadequate bowel preparation |

| (OR = 0.17, 95%CI: 0.14-0.21, P < 0.001) |

OR: Odd ratio.

The quality of bowel preparation also greatly influences the cost of the colonoscopy; notably, it was estimated that inadequate bowel preparation increased the cost of the colonoscopy by 12%-22% (which is attributable to the increased duration of the examination as well as the need for repeated procedures or anticipated surveillance)[22].

Another variable related to the efficiency and quality of the colonoscopy is the colonoscope withdrawal time. A study of 99 patients undergoing colonoscopy reported a shorter mean withdrawal time when the quality of colon cleansing was adequate (4.4 min vs 5.8 min for an inadequate preparation, P < 0.001)[23]. Similarly, Froehlich et al[13] reported a significantly shorter mean withdrawal time in patients with high-quality colon cleansing (n = 3445) than in patients with a poor preparation (n = 360; 9.8 min vs 11.3 min, P < 0.001). In this study, the shorter withdrawal time did not adversely affect the efficacy of the colonoscopy because the detection of polyps was more frequent in patients with a high-quality vs a low-quality cleansing.

BOWEL PREPARATION AND DIAGNOSTIC YIELD

In addition to affecting the speed and the completeness of a colonoscopy, the quality of colon cleansing can affect the detection of adenomas and CRCs. In a retrospective evaluation of more than 5000 colonoscopies performed over a 3.5-year period, Leaper et al[24] identified 17 patients with a missed CRC. Poor bowel preparation was noted in six of these patients, which suggested that cleansing quality might influence the diagnostic yield of a colonoscopy. In a larger retrospective study, Harewood et al[14] analyzed the impact of the quality of the bowel preparation on the detection of polypoid lesions in approximately 93000 colonoscopies recorded in the Clinical Outcome Research Initiative database. Suspected neoplasms were identified in 26490 colonoscopies (29%) overall; detection rates were higher in cases with adequate preparation (rated excellent or good by the endoscopist) than in those with inadequate preparation (fair or poor) (29% vs 26%, P < 0.0001). Although significant lesions (polyps > 9 mm or mass lesions) were detected in approximately 7% of these colonoscopies regardless of the preparation quality (P = 0.82), smaller lesions, ≤ 9 mm, were more likely to be detected when bowel preparation was adequate [15615 cases (22%)] than when it was inadequate [4092 cases (19%), P < 0.0001]. Thus, the detection of a suspected neoplasia was critically dependent on the adequacy of the preparation (OR = 1.21, 95%CI: 1.16-1.25)[14]. These findings were supported by another study of 5832 patients. These investigators reported that the detection of neoplasms, including polyps of any size as well as large lesions (> 10 mm), was associated with the quality of bowel preparation; polyps were detected more frequently in patients with high-quality cleansing than in patients with low-quality cleansing (29% vs 24%, P < 0.007). The identification of polyps of any size was significantly associated with cleansing quality (intermediate-quality vs low-quality preparation: OR = 1.73, 95%CI: 1.28-2.36; high-quality vs low-quality preparation: OR = 1.46, 95%CI: 1.11-1.93). For polyps ≥ 10 mm in size, the OR was 1.83 (95%CI: 1.11-3.05) for intermediate-quality cleansing and 1.72 (95%CI: 1.11-2.67) for high-quality cleansing[13]. Flat and depressed neoplasms, which are common among Japanese populations, are increasingly reported in Western countries[25,26]. Although flat and depressed lesions are rarer than protruding lesions, they more frequently contain advanced neoplasia, including invasive carcinoma[26,27]. In one study, the number of flat lesions detected in patients with inadequate bowel preparation was significantly fewer than in patients with adequate bowel preparation (9 vs 28, P = 0.002)[28].

Medico-legal risks, which are due to colon cancers that are missed due to an improperly performed colonoscopy, are another important consequence of inadequate bowel preparation. Of note, the accurate description and documentation of good colon cleansing are important issues in the malpractice litigation of CRCs discovered after “apparently negative” total colonoscopies[29].

Although guidelines advocate a repeat colonoscopy when a suboptimal bowel preparation is detected[30,31], in practice, shortening the interval to the next colonoscopy is often recommended despite the lack of evidence to support this management approach[32]. To assess the validity of such an approach, the relationship between bowel preparation quality and the risk of missing polyps, adenomas and advanced adenomas during the screening colonoscopy should be investigated.

CONCLUSION

In summary, it is clear that suboptimal bowel preparation not only prolongs the overall procedure time, decreases the cecal intubation rate and increases the costs associated with colonoscopy but also increases the risk of missing polyps or adenomas during the colonoscopy. Bowel preparation is one of the most frequent reasons why patients object to participating in screening colonoscopies, and inadequate preparation is a major obstacle to achieving a high-quality colonoscopy. Therefore, a repeat examination or shorter colonoscopy follow-up interval may be suitable strategies for patients with suboptimal bowel preparations. In the future, large-scale multi-center studies will be needed to evaluate the frequency of missing polyps and adenomas according to the bowel preparation status in average-risk patients undergoing screening colonoscopy and to further describe the risk of developing interval cancer as well as to compare the cost-effectiveness of repeat colonoscopy to the shortening of the colonoscopy follow-up interval in patients with suboptimal bowel preparations.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Rodrigo L, Redondo-Cerezo E, Tanaka S S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ransohoff DF. Colon cancer screening in 2005: status and challenges. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1685–1695. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, Bond J, Burt R, Ferrucci J, Ganiats T, Levin T, Woolf S, Johnson D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignone M, Saha S, Hoerger T, Mandelblatt J. Cost-effectiveness analyses of colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:96–104. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrar WD, Sawhney MS, Nelson DB, Lederle FA, Bond JH. Colorectal cancers found after a complete colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1259–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bressler B, Paszat LF, Chen Z, Rothwell DM, Vinden C, Rabeneck L. Rates of new or missed colorectal cancers after colonoscopy and their risk factors: a population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:96–102. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosokawa O, Shirasaki S, Kaizaki Y, Hayashi H, Douden K, Hattori M. Invasive colorectal cancer detected up to 3 years after a colonoscopy negative for cancer. Endoscopy. 2003;35:506–510. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bond JH. Should the quality of preparation impact postcolonoscopy follow-up recommendations? Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2686–2687. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pabby A, Schoen RE, Weissfeld JL, Burt R, Kikendall JW, Lance P, Shike M, Lanza E, Schatzkin A. Analysis of colorectal cancer occurrence during surveillance colonoscopy in the dietary Polyp Prevention Trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02765-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:873–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:S16–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zwierko M, Rupinski M, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1795–1803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378–384. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:76–79. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, Levin TR, Burt RW, Johnson DA, Kirk LM, Litlin S, Lieberman DA, Waye JD, et al. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1296–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke CA, Church JM. Enhancing the quality of colonoscopy: the importance of bowel purgatives. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:565–573. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.03.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowles CJ, Leicester R, Romaya C, Swarbrick E, Williams CB, Epstein O. A prospective study of colonoscopy practice in the UK today: are we adequately prepared for national colorectal cancer screening tomorrow? Gut. 2004;53:277–283. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.016436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein C, Thorn M, Monsees K, Spell R, O’Connor JB. A prospective study of factors that determine cecal intubation time at colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:72–75. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim WH, Cho YJ, Park JY, Min PK, Kang JK, Park IS. Factors affecting insertion time and patient discomfort during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:600–605. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.109802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson DB, McQuaid KR, Bond JH, Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Johnston TK. Procedural success and complications of large-scale screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:307–314. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.121883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aslinia F, Uradomo L, Steele A, Greenwald BD, Raufman JP. Quality assessment of colonoscopic cecal intubation: an analysis of 6 years of continuous practice at a university hospital. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:721–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1696–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kössi J, Kontula I, Laato M. Sodium phosphate is superior to polyethylene glycol in bowel cleansing and shortens the time it takes to visualize colon mucosa. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1187–1190. doi: 10.1080/00365520310006180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leaper M, Johnston MJ, Barclay M, Dobbs BR, Frizelle FA. Reasons for failure to diagnose colorectal carcinoma at colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2004;36:499–503. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuda S, Veress B, Tóth E, Fork FT. Flat and depressed colorectal tumours in a southern Swedish population: a prospective chromoendoscopic and histopathological study. Gut. 2002;51:550–555. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.4.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross AS, Waxman I. Flat and depressed neoplasms of the colon in Western populations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:172–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'brien MJ, Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Bushey MT, Sternberg SS, Gottlieb LS, Bond JH, Waye JD, Schapiro M. Flat adenomas in the National Polyp Study: is there increased risk for high-grade dysplasia initially or during surveillance? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:905–911. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parra-Blanco A, Nicolas-Perez D, Gimeno-Garcia A, Grosso B, Jimenez A, Ortega J, Quintero E. The timing of bowel preparation before colonoscopy determines the quality of cleansing, and is a significant factor contributing to the detection of flat lesions: a randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6161–6166. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i38.6161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rex DK, Bond JH, Feld AD. Medical-legal risks of incident cancers after clearing colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:952–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Fletcher RH, Stillman JS, O’Brien MJ, Levin B, Smith RA, Lieberman DA, Burt RW, Levin TR, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1872–1885. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Johnson D, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ben-Horin S, Bar-Meir S, Avidan B. The impact of colon cleanliness assessment on endoscopists’ recommendations for follow-up colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2680–2685. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]