Abstract

Background:

The purpose of this study was to compare the functional outcomes and quality of life of older and younger patients with similarly treated distal femur fractures.

Methods:

We conducted an assessment of 57 patients who sustained distal femur fractures (Orthopaedic Trauma Association Type 33B, C) and underwent surgical treatment at our academic medical center. Patients were divided into 2 groups for analysis: an elderly cohort of patients aged 65 or older and a comparison cohort of patients younger than age of 65. A retrospective review of demographics, preoperative ambulatory status, radiographic data, and physical examination data was collected from the medical records. Follow-up functional data were collected via telephone at a mean of 2.5 years (range 6 months-8 years) using a Short Musculoskeletal Functional Assessment (SMFA). All patients underwent standard operative treatment of either nail or plate fixation.

Results:

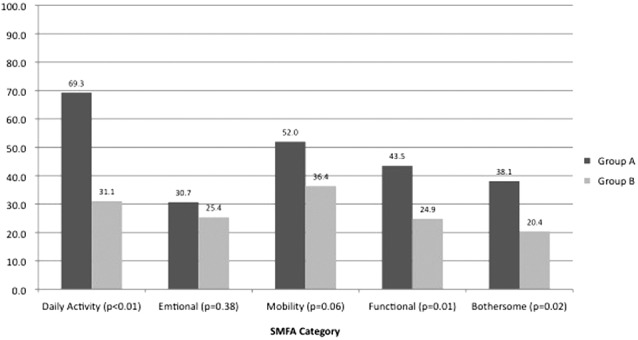

There was no statistical difference in gender, fracture type, surgical technique, surgeon, or institution where the surgery was performed. The percentage of patients with healed fractures at 6-months follow-up was not significantly different between the cohorts. The elderly cohort had slightly worse knee range of motion at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively but there was not a statistically significant difference between the groups. The SMFA Daily Activity, Functional, and Bother indices were significantly worse in the older cohort (P < .01, P = .01, P = .02, respectively). However, there was no significant difference in the SMFA Emotional or Mobility indices.

Conclusion:

Despite lower quality of life and functional scores, this study suggests that relatively good clinical outcomes can be achieved with surgical fixation of distal femoral fractures in the elderly patients. Age should not be used as a determinate in deciding against operative treatment of distal femur fractures in the elderly patients.

Keywords: geriatric trauma, trauma surgery, distal femur fracture, functional outcomes, lower extremity surgery

Introduction

Distal femoral fractures account for approximately 6% of all femoral fractures.1 They tend to occur in a bimodal distribution, with young adults incurring fractures secondary to high-energy trauma and the elderly patients following low-energy trauma.1,2 It is estimated that fractures resulting from low-energy trauma in patients older than 50 years of age account for as much as 85% of all distal femur fractures.2 Moreover, the incidence of such injuries is expected to rise with our aging and increasingly mobile population.1,3

Operative fixation for distal femur fractures in the elderly patients has been utilized with varying success since the 1970s.2 Schatzker et al in their 1974 review of 68 patients with distal femur fractures did not endorse open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) for all patients.4 They recommended cast treatment for all elderly patients with easily reducible fractures.4 Further, they described using internal fixation to treat patients with osteoporosis as “doomed” due to device failure, malunion, and nonunion as frequent complications.4 Largely because of these difficulties, Karpman and Mar in 1995 went as far as recommending above-knee amputations for patients with severe osteoporosis having distal femur fractures.5 However, in the recent years the results of internal fixation, even in the elderly patients, have generally been more favorable than conservative treatment with traction or cast bracing.2,6–8 Although distal femur replacing total knee replacement, angled blade plates, and other methods have been successfully used to treat distal femur fractures in the elderly patients, locked plating and intramedullary nailing remain the current standards of operative care.9–12 Nevertheless, high rates of complications and mortalities continue to be reported in all methods of internal fixation for distal femur fractures in the elderly patients.1,2,8,13

Although multiple studies have assessed the biomechanical properties, functional scores, and complication rates of surgical treatment for distal femur fractures in the elderly patients, few studies have investigated the patient’s quality of life.14 The short- and long-term consequences of distal femur fracture treatment in the elderly patients can have a substantial impact on patients’ quality of life, which is difficult to measure with radiographic and functional scores alone. To our knowledge, no study to date has investigated patients’ quality of life following the surgical treatment of distal femur fractures as stratified by age. Thus, the purpose of this study was to compare functional outcomes and quality of life in old and young patients with similarly treated distal femur fractures. Our null hypothesis was that there would be significant differences in the clinical, radiographical, and overall functional outcomes of older patients as compared to younger patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of all patients who sustained a displaced intra-articular distal femur fractures (Orthopaedic Trauma Association Type 33B, C15) and underwent surgical treatment at our academic medical center based on age. A cohort that included all patients older than age 65 was identified, group A. A second cohort that sustained similar injuries but was younger than age 65 was identified and utilized as a comparison group, group B. Every patient who underwent operative treatment by 1 of the 2 surgeons for a distal femur fracture from 2001 through 2012 at our medical center was called for follow-up (92 patients). Final follow-up was collected via telephone using a Short Musculoskeletal Functional Assessment (SMFA) to assess function and quality of life. All patients gave their informed consent prior to being included into the study; this study was authorized by the local ethical committee and was performed in accordance with the Ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000.

All patients underwent standard operative treatment of either intramedullary nail or locking plate fixation. A retrospective review of demographics, radiographic data, and physical examination data was collected from the medical records. All patients were seen for outpatient follow-up at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. Fracture union was assessed based on radiographic data obtained at each follow-up visit. The presence of preinjury osteoarthritis was determined based on the Kellgren-Lawrence scale.16 Knee flexion and knee extension at each follow-up interval were recorded. Patients were not included in our retrospective review if they were less than 18 years old at the time of initial treatment. Patients were also excluded from this study if they initially sustained a pathologic fracture or if they could not be contacted for the SMFA.

Statistical analysis was conducted to calculate differences between group A and group B. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to determine differences in all SMFA categories, time until observed fracture union, knee range of motion, and radiographic measurements. Fischer exact tests were used to compare differences in gender, intra-articular extension, surgical technique, and complications. Statistical tests were considered to be significant if 2-tailed P < .05.

Results

Fifty-seven patients met the inclusion criteria for this study (Table 1). Eight (21%) patients in Group A had died by before the final follow-up. One patient in group B was excluded due to preinjury lower extremity paralysis. This left 48 patients available for potential follow-up. Group A included 30 patients with an average age of 78 years (standard deviation [SD] 10, range 65-97). Group B included 18 patients with an average age of 47 years (SD 13, range 20-64). Follow-up functional data were collected at a mean of 2.5 years (SD 2.2 years, range 6 months-8 years). There was no statistical difference in gender, fracture type, surgical technique, or follow-up interval (Table 1). The percentage of patients with healed fractures at 6-month follow-up was 94% in group A and 80% in group B. This difference was not significant (P = .78). The elderly cohort had slightly worse range of knee motion at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively but there was not a statistically significant difference between the groups (Table 2). There were more complications in group A (6 of 30, 20%) than in group B (1 of 18, 6%; Table 3). The SMFA’s Daily Activity, Functional, and Bother indices were significantly worse in the older cohort (Figure 1). However, there was no significant difference in the SMFA Emotional or Mobility indices. Group A had a mean alignment of 7.0° valgus while group B had a mean alignment of 6.4° valgus. This difference was not significant (P = .52). Group A had a mean Kellgren-Lawrence score of 2.83 while group B had a mean score of 1.54. This difference was significant (P = .01).

Table 1.

Demographic and Radiographic Information.a

| Group A | Group B | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Met inclusion criteria, n | 38 | 19 | |

| Included for analysis, n | 30 | 18 | |

| Died by latest follow-up, n | 8 | 0 | |

| Mean age | 78 | 47 | <.01 |

| Female, n | 24 (80%) | 11 (61%) | .19 |

| ORIF with plate, n | 12 (67%) | 27 (90%) | .06 |

| Intra-articular extension, n | 7 (23%) | 4 (22%) | 1.00 |

| Mean follow-up interval, years | 2.1 | 2.8 | .35 |

Abbreviation: ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation.

a Group A, 65 years and older; group B, younger than 65 years.

Table 2.

Physical Examination Scores.a

| Group A (Degrees) | Group B (Degrees) | P Value Extension | P value Flexion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-month flexion arc | 1.73-90.96 | 1.07-97.86 | .77 | .17 |

| 6-month flexion arc | 1.30-100.19 | 0.36-105.00 | .44 | .15 |

| 12-month flexion arc | 3.21-99.23 | 1.00-101.59 | .28 | .31 |

a Group A, 65 years and older; group B, younger than 65 years.

Table 3.

Complications.a

| Group | Complication | Age |

|---|---|---|

| Group A | Screw back-out | 65 |

| Painful hardware | 65 | |

| Tear of quadriceps tendon | 66 | |

| DVT | 67 | |

| Nonunion | 69 | |

| Knee stiffness requiring reoperation | 73 | |

| Group B | Infected nonunion | 20 |

Abbreviation: DVT, deep venous thrombosis.

a Group A, 65 years and older; group B, younger than 65 years.

Figure 1.

Mean Short Musculoskeletal Functional Assessment (SMFA) scores. SMFA scores from latest follow-up; lower scores represent better function. Group A, 65 years and older; group B, younger than 65 years.

Discussion

Old and young patients alike had satisfactory outcomes following surgical treatment for distal femur fractures. The percentage of patients with fracture union at 6-month follow-up and the range of motion scores at every interval were not significantly different between the groups. A large proportion of older patients had died at the time of latest follow-up (mean 2.5 years). Although the SMFA’s Daily Activity, Functional, and Bother indices were significantly worse in the older cohort, the Emotional and Mobility indices were not. Overall, we disproved our null hypothesis as many of the assessment parameters were similar between the age groups.

Our mortality rate was similar to that of proximal femoral fractures in the elderly patients.17 Previous studies investigating postoperative function following distal femur fracture repair have also reported high mortality rates for elderly patients following distal femur fracture repair. Dunlop and Brenkel in a 1999 prospective study of 30 elderly patients with intramedullary nails reported a mortality rate of 17% at 6 months and 30% at 1 year.2 Streubel et al reported a 25% 1-year mortality in elderly patients treated surgically for distal femur fractures.13 Kammerlander et al, in a long-term study of 53 elderly patients treated operatively for distal femur fractures, reported that 48.8% of patients died within 5.3 years of surgery.1 The majority of deaths reported in all studies were not attributed to procedure-related complications but rather to unrelated medical problems.1,2,13 Both Kammerlander et al and Streubel et al and reported strong associations between mortality and the presence of medical comorbidities.1,13 Like hip fractures, distal femur fractures in the elderly patients may be a sign of poor overall health rather than a direct cause for mortality.1,13 Similarly, in our study, we are unable to pinpoint the cause of the mortality and whether the fracture contributed to the increased mortality or the presence of associated medical comorbidities.

Although we found that the SMFA’s Daily Activity, Functional, and Bother indices were worse in elderly patients, patients in both the age groups still reported fairly good functional and quality-of-life scores (Figure 1). Furthermore, the percentage of patients healed at 6-month follow-up, range of motion scores at all follow-up intervals, and the rate of complications at 1 year were not statistically different between the age groups. Thus, we contend that for active patients who are healthy enough to survive their first postoperative year, good outcomes can be achieved regardless of age. This is also corroborated in the existing literature. For their surviving patients, Dunlop and Brenkel reported that 85% had excellent or satisfactory function 1 year following surgery.2 Kim et al in a small study of elderly patients with retrograde nails reported that all 13 living patients in their cohort were satisfied with their surgical results at 2-year follow-up.18 We suspect that the decrease in quality of life and functional scores in group A would also be seen in healthy patients older than age 65. Since baseline SMFA scores were not collected, we were unable to prove our supposition that group A had a lower baseline status than group B. However, this was corroborated by Barei et al who report that normative “uninjured” mean SMFA scores for patients older than 60 years are more than twice as high as for patients aged 30 to 44.19 Furthermore, group A had a significantly higher degree of preinjury osteoarthritis than group B which is an established cause of decreased functional status.

One strength of our study was that both group A and group B were largely similar in their makeup. Besides the intentional age difference, there were no statistically significant differences in gender or devices used for fixation. Although the surgical treatment did trend toward more older patients being treated with ORIF, we do not feel that this greatly impacted patient-centered outcomes. Thomson et al, in one of the few studies to use a quality-of-life assessment to evaluate distal femur fracture patients, previously compared patients treated with ORIF to patients treated with intramedullary nails.14 They reported no differences in SMFA scores between patients treated with ORIF and intramedullary nails but did not evaluate differences in age.14

Our study was limited by its retrospective assessment of physical examination and radiographic scores. It was also limited by our ability to contact patients via telephone for SMFA follow-up. The exclusion of patients who we were unable to contact may have introduced bias in our results. This may have led to an underreporting of patient complications and mortality, especially in the older cohort. We were also not able to accurately assess statistical differences in the complication rates between cohorts due to the size of our study. Furthermore, this study did not assess other viable surgical treatments such as knee replacement or fixed angle plating. It is possible that patients treated with other validated modalities would have different SMFA scores.

Despite lower quality of life and functional scores, this study suggests that relatively good clinical outcomes can be achieved with surgical fixation in the elderly patients. The mortality rate following this injury in elderly patients approaches that of hip fractures and physicians should counsel families regarding that fact. We recommend that elderly patients with distal femur fractures should be assessed for surgical candidacy based on their preinjury functional status, medical comorbidities, and mental status. Age should not be a strong consideration in deciding against operative treatment of distal femur fractures in the elderly patients.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The investigation was performed at NYU and Jamaica Hospital medical center

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Brandon Shulman, Bianka Patsalos-Fox, Nicole Lopez, and Sanjit Konda report no disclosures. Nirmal Tejwani is a consultant for Stryker and Zimmer is on the editorial board of Am J Orthopaedics and is a board member of the Federation of Orthopaedic Trauma (FOT). Kenneth Egol is a consultant for and receives royalties from Exactech, receives institutional grants from Synthes, OREF, and Omega, and owns stock in Johnson and Johnson.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Kammerlander C, Riedmuller P, Gosch M, et al. Functional outcome and mortality in geriatric distal femoral fractures. Injury. 2012;43(7):1096–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dunlop DG, Brenkel IJ. The supracondylar intramedullary nail in elderly patients with distal femoral fractures. Injury. 1999;30(7):475–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cornell CN, Ayalon O. Evidence for success with locking plates for fragility fractures. HSS J. 2011;7(2):164–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schatzker J, Home G, Waddell J. The Toronto experience with the supracondylar fracture of the femur, 1966-72. Injury. 1974;6(2):113–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karpman RR, Del Mar NB. Supracondylar femoral fractures in the frail elderly. Fractures in need of treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995(316):21–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shahcheraghi GH, Doroodchi HR. Supracondylar fracture of the femur: closed or open reduction? J Trauma. 1993;34(4):499–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heiney JP, Barnett MD, Vrabec GA, Schoenfeld AJ, Baji A, Njus GO. Distal femoral fixation: a biomechanical comparison of trigen retrograde intramedullary (i.m.) nail, dynamic condylar screw (DCS), and locking compression plate (LCP) condylar plate. J Trauma. 2009;66(2):443–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. El-Kawy S, Ansara S, Moftah A, Shalaby H, Varughese V. Retrograde femoral nailing in elderly patients with supracondylar fracture femur; is it the answer for a clinical problem? Int Orthop. 2007;31(1):83–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Appleton P, Moran M, Houshian S, Robinson CM. Distal femoral fractures treated by hinged total knee replacement in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(8):1065–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Assari S, Kaufmann A, Darvish K, et al. Biomechanical comparison of locked plating and spiral blade retrograde nailing of supracondylar femur fractures. Injury. 2013;44(10):1340–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pearse EO, Klass B, Bendall SP, Railton GT. Stanmore total knee replacement versus internal fixation for supracondylar fractures of the distal femur in elderly patients. Injury. 2005;36(1):163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vallier HA, Immler W. Comparison of the 95-degree angled blade plate and the locking condylar plate for the treatment of distal femoral fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(6):327–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Streubel PN, Ricci WM, Wong A, Gardner MJ. Mortality after distal femur fractures in elderly patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1188–1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thomson AB, Driver R, Kregor PJ, Obremskey WT. Long-term functional outcomes after intra-articular distal femur fractures: ORIF versus retrograde intramedullary nailing. Orthopedics. 2008;31(8):748–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium - 2007: orthopaedic trauma association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10 suppl):S1–S133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16(4):494–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Egol KA, Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD. Handbook of Fractures. 4th ed Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim J, Kang SB, Nam K, Rhee SH, Won JW, Han HS. Retrograde intramedullary nailing for distal femur fracture with osteoporosis. Clin Orthop Surg. 2012;4(4):307–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barei DP, Agel J, Swiontkowski MF. Current utilization, interpretation, and recommendations: the musculoskeletal function assessments (MFA/SMFA). J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10):738–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]