Abstract

Addiction appointment no-shows adversely impact clinical outcomes and healthcare productivity. During 2007–2010, 67 treatment organizations in the Strengthening Treatment Access and Retention program were asked to reduce their no-show rates by using practices taken from no-show research and theory. These treatment organizations reduced outpatient no-show rates from 37.4% to 19.9% (p = .000), demonstrated which practices they preferred to implement, and which practices were most effective in reducing no-show rates. This study provides an applied synthesis of addiction treatment no-show research and suggests future directions for no-show research and practice.

Keywords: addiction, no-shows, attendance, continuous quality improvement, patient adherence

INTRODUCTION

“You cannot treat an empty chair.” (Clark, 2010). No-shows, or missed appointments, represent a common phenomenon in health care (Lasser, Mintzer, Lambert, Cabral, & Bor, 2005). They affect health care productivity as clinicians wait for patients who never arrive (Stone, Palmer, Saxby, & Devaraj, 1999). They also affect outcomes, as missed appointments are correlated with treatment length of stay and abstinence—two predictors of addiction outcomes and health (Craig & Olson, 2004; Leigh, Ogborne, & Cleland, 1984). Appointment no-shows are prevalent in addiction treatment settings, with 29%–42% failing to begin treatment (Weisner, Mertens, Tam, & Moore, 2001) and 15%–50% not returning for a second appointment (Mitchell and Selmes, 2007; McCarty et al., 2007; Festinger, Lamb, Marlowe, & Kirby, 2002).

Studies investigating how to reduce no-show rates have examined the effectiveness of practices such as reducing waiting times and using appointment reminders, along with behavioral engagement strategies such as contingency management and motivational interviewing. Williams, Latta, & Conversano (2008) demonstrated that when wait times were reduced from 13 to 0 days in out-patient mental health settings, no-shows dropped from 52%–18%. Wait times can occur when demand outpaces capacity. Adding more counselors and appointments can accommodate demand for treatment. In other instances, streamlining processes reduces the workload of intake specialists, increasing their capacity to meet higher demand (Sears, Davis, Guydish, & Gleghorn, 2009).

Clinical capacity is poorly utilized when clients fail to attend scheduled appointments. Reminder phone calls are a common practice used to increase appointment attendance in general medicine and dentistry (Lee and McCormick, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 2003; Roth, Kula Jr, Glanos, & Kula, 2004). Using reminder phone calls, however, has produced mixed results in reducing no-shows in addiction treatment (Maxwell et al., 2001; Jackson, Booth, Salmon, & McGuire, 2009). In general health, staff reminder calls reduced no-show rates from 23.1% to 13.6% (Parikh et al., 2010).

While the purpose of the reminder phone calls is to prevent patients from forgetting appointments, the purpose of evidence-based behavioral engagement strategies is to make patients want to attend their appointments. Contingency management and motivational interviewing are two behavioral engagement strategies shown to enhance appointment attendance (Prendergrast, Podus, Finney, Greenwell, & Roll, 2006; Carroll et al., 2006). Contingency management provides financial or other incentives for appointment attendance (Roll, Huber, Sodano, et al, The Psychological Record, 2006) and motivational interviewing techniques seek to help individuals recognize and resolve ambivalence about changing their behavior and build internal motivation to attend their therapeutic sessions (Miller & Rose, American Psychologist, 2009).

Creating a welcoming environment and partnering with referral sources have also been shown to reduce no-show rates, but these practices have received limited attention in the no-show literature. Like all healthcare consumers, people seeking addiction treatment services are more satisfied with well-decorated, clean, and orderly environments, and this is expected to encourage them to return to treatment services (Tsai et al., 2007). A treatment center with an attractive and welcoming environment may also be more appealing to the entities (such as managed care plans and the criminal justice system) that refer clients to treatment.

The collaborative interaction between referral sources and addiction treatment centers is projected to influence addiction consumer engagement patterns (McCarty & Chandler, 2009). For instance, collaborating with referral sources to provide the patient a financial incentive for completing has been shown to reduce treatment no-shows (Chutuape, Katz, & Stitzer, 2001).

Collaborating with referral sources, reducing wait times, making reminder calls, using behavioral engagement strategies, and creating a welcoming environment are all practices that have been shown to reduce no-show rates. However, the practices most effective in reducing no-show rates in addiction treatment settings have not been thoroughly studied. In addition, the practices described in literature have only been tested or developed in isolated settings, with no comparison to other interventions. Accordingly, this study will address two research questions. What practices do addiction treatment organizations choose to implement to prevent no-shows? How do these practices affect no-show rates?

Setting

In 2007, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) launched the national Strengthening Treatment Access and Retention—State Initiative (STAR-SI). Ten states participated in this competitive grant program, with funding from multiple sources. SAMHSA sponsored seven states: Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Ohio, South Carolina, and Wisconsin; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation sponsored New York and Oklahoma; and Montana participated without grant support. Each state recruited treatment agencies to participate in the program. When recruiting treatment organizations, the states were instructed to consider sites with diverse locations (urban and rural) and financial standing (weak and strong) to ensure that results would be generalizable to the broader field of addiction treatment organizations in the United States.

The grant required each STAR-SI state grantee to:

Recruit up to 15 treatment organizations committed to improving organizational processes that affect clients’ access to and or retention in outpatient treatment.

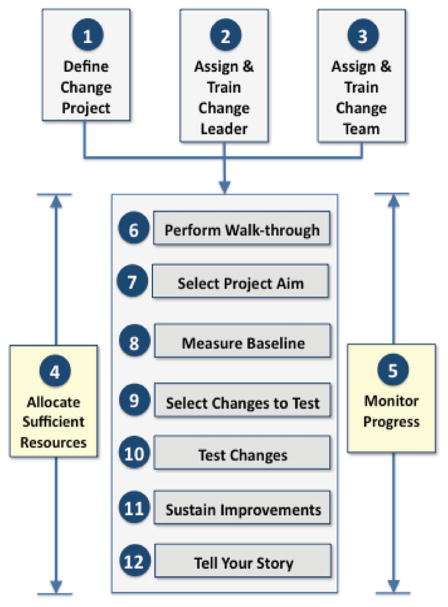

Use a standard set of performance improvement methods, called the NIATx organizational change model (Figure 1), provided by the STAR-SI program to each treatment organization through two face-to-face meetings, monthly webinars, and monthly coaching over a 12-month period.

Establish systems to track progress toward goals.

FIGURE 1.

NIATx organizational change model.

The NIATx organizational change model was used by Rutkowski et al. (2010) to reduce no-shows rates from 43.5% to 24.6% over six months. This research, however, was limited to four treatment organizations in one state (California), and the sample was not large enough to determine which changes to organizational processes produced the best results on no-show rates. Within the STAR-SI program, 67-treatment programs conducted no-show reduction projects. The no-show rate reduction practices applied in this program and their effect on no-show rates is summarized in the analysis.

METHODS

Study Population

The study population included 67 substance use disorder outpatient clinics in 10 states participating in the STAR-SI project.

No-Show Practices Studied

Providers in the STAR-SI project were asked to consider any of the following practices to reduce no-shows: Make reminder calls, try behavioral engagement strategies such motivational interviewing or contingency management, reduce wait-time times, add capacity, streamline admissions, create a welcoming environment through decoration changes, and collaborate with referrers (ask the referring entity to offer an incentive for attendance, or in the case of criminal justice, a penalty for failure to attend.)

Data Collection

From January 2008 to August 2010, STAR-SI treatment organizations self-reported data in quarterly reports submitted to the research team. The reports included the interventions attempted to reduce no-show rates and their no-show rate data. The research team reviewed these reports for completeness and accuracy. The primary dependent variable for this analysis is the no-show rate. The no-show rate definition used was calculated by dividing the number of missed appointments by the number of expected visits (no-shows/scheduled appointments). All organizations eligible for the analysis had no-show projects that extended at least six months. The independent variables were the practices attempted to reduce no-show rates. These practices were coded by author and another researcher independently, cross-checked for consistency, and recoded when discrepancies in coding occurred. Only organizations that had reduced wait times by >10% were designated as implementing the “reducing wait time” practice. The authors also considered the effect of rural versus urban designation on no-show rates, since the lack of public transportation in rural areas reduces health care appointment attendance (Arcury, Preisser, Gesler, & Powers, 2005).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported by percentage for initial no-show rates by urban versus rural designation, treatment organization admission rates, and individual states. An initial analysis of whether the state rural/urban designation is associated with initial and postintervention implementation no-show rates was conducted using an ANOVA analysis. A treatment program was considered rural if its zip code met the criteria established by the United States Department of Agriculture1. The analysis did not include state-specific effects, since regional differences due to no-shows have not been found in the literature and all states implemented a similar organizational change intervention. For no-show practice implementation, descriptive statistics were applied to the frequency of no-show practice use; mean initial no-show and post-no-show rates, as well as the difference between initial and post no-show rates. An ANOVA analysis was conducted to determine the effect the different no-show practices had on the difference between initial and post no-show rates. All analyses were conducted in SPSS (Version 20).

RESULTS

Sixty-seven agencies from ten states were included in the analysis. The number of treatment agencies included in the analysis by state in descending order are: Wisconsin (n = 13); Iowa (n = 10); Oklahoma (n = 8); New York & Montana (n = 7); Ohio (n = 6); and Florida, Illinois, Maine, and South Carolina (n = 4). In the study, there was nearly an equal split between urban and rural treatment agencies, and 62.7% of the treatment organizations had admissions of 101–500 per annum (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline descriptive statistics

| Parameter | No-show rate (STD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment organization location | Urban = 51% (n = 34) | 40% (.128) |

| Rural = 49% (n = 33) | 34% (.154) | |

| Treatment organization admissions (per annum) | 0–100 = 22% (n = 15) | 33% (.157) |

| 101–500 = 62% (n = 42) | 38% (.155) | |

| 500–1000 = 15% (n = 9) | 35% (.061) | |

| 1000+ = 1% (n = 1) | 54% |

| State | No-Show Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Average (STD) | |

| A | 20% | 40% | 32% (.084) |

| B | 12% | 80% | 35% (.200) |

| C | 32% | 40% | 38% (.040) |

| D | 09% | 64% | 37% (.238) |

| E | 15% | 51% | 35% (.152) |

| F | 21% | 65% | 39% (.065) |

| G | 14% | 61% | 32% (.055) |

| H | 22% | 66% | 45% (.042) |

| I | 52% | 54% | 53% (.010) |

| J | 17% | 61% | 36% (.036) |

| Overall | 09% | 80% | 37% (.147) |

No-Show Rate Analysis

The mean difference between initial no-shows, occurring before no-show practice implementation, and post-no-shows, occurring after no-show practice implementation, was +16.48%. (preaverage = 37.4% vs. postaverage = 19.72%) and represented a significant reduction in no-show rates (p = .000) (Table 2). The range of initial no-shows was 71% (9%–80%); and the range of post no-shows was 41% (0%–41%). The initial no-show rate for rural treatment organizations was higher than for urban treatment organizations (40% vs. 34%) (p = .022). However, the implementation of the STAR-SI program eliminated the difference of post no-show rates between rural and urban locations (22% vs. 19%) (p = .271).

TABLE 2.

No-show intervention descriptive statisticsa

| Interventions attempted | nb | Initial no-show (STD) | Post-no-show (STD) | No-show difference (STD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 37.4% (.15) | 20.0% (.11) | 17.4% (.12) | |

| Reminder calls | 42 | 36.3% (.18) | 19.5% (.15) | 16.8% (.12) |

| Behavioral engagement strategies | 11 | 42.8% (.11) | 22.1% (.11) | 20.7% (.12) |

| Reduce wait time | 11 | 41.7% (.19) | 21.2% (.0) | 20.2% (.11) |

| Streamline admissions | 8 | 47.6% (.16) | 27.8% (.03) | 19.8% (.12) |

| Add capacity | 6 | 44.0% (.15) | 19.7% (.09) | 24.3% (.11) |

| Create welcoming environment (through décor changes) | 6 | 28.7% (.12) | 22.8% (.09) | 5.9% (.08) |

| Collaborate with referrers | 4 | 50.0% (.14) | 29.3% (.05) | 20.7% (.09) |

Treatment organizations could implement more than one intervention.

Number of treatment organizations who implemented the intervention.

No-Show Intervention Results

Table 2 lists the frequency of no-show practice implementation and the pre- and post-no-show rates for each practice implemented. The most popular intervention attempted was reminder calls with 64% (n = 42) of treatment agencies attempting them. Treatment organizations that had average initial no-show rates greater than the initial no-show average of 37.4% (Table 2) attempted behavioral engagement strategies such as contingency management and motivational interviewing. They also used strategies to reduce wait time, streamline admissions, add capacity, and collaborate with referral sources. Adding capacity made the greatest average difference between initial and post-no-show rates (difference = 24%).

ANOVA Analysis

An ANOVA analysis (including the seven different practices applied) possessed an r-squared = .227 (df = 65) at p = .029. All practices implemented did have a positive impact on the difference between initial and post no-show rates (Table 2). However, only four factors demonstrated a (p < .10) in the analysis comparing pre- to postpractice implementation differences. These were: creating a welcoming environment (p = .019), reduce wait times, (p = .025), adding capacity (p = .051), and behavioral engagement strategies (p = .046). Creating a welcoming environment through decoration changes was significant, (p = .027), but did have a negative Beta coefficient (Table 3). Organizations that worked on creating a welcoming environment all focused on improving the appearance of the public entrance areas. Examples of interventions used to increase capacity included adding new groups at new times (e.g., evenings and Saturdays) (n = 1); adding new types of groups (e.g., pretreatment and vocational) (n = 2); and adding more appointment slots (n = 3). Those reducing wait times by >10% implemented walk-in appointments (n = 7); double-booked appointments (n = 3); and centralized appointment scheduling (vs. counselor scheduling (n = 1). Behavioral engagement strategies included motivational interviewing (n = 4) and contingency management (n = 7).

TABLE 3.

Multivariate ANOVA analysis

| Variable | B | Sig. | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | .112 | .003 | [.040, .184] |

| Reminder calls | .024 | .225 | [−.027, .113] |

| Create welcoming environment | −.114 | .019 | [−.208, −.019] |

| Add capacity | .099 | .051 | [.000, .198] |

| Reduce wait times | .101 | .025 | [.013, .189] |

| Collaborate with referrers | .067 | .281 | [−.056, .190] |

| Streamline admissions | .010 | .831 | [−.081, .101] |

| Behavioral engagement strategies | .078 | .046 | [.001, .156] |

DISCUSSION

Appointment no-shows have an adverse effect on clinic workflow and clinical outcomes (Lacy, Paulman, Reuter, & Lovejoy, 2004; Craig & Olson, 2004). The 67 treatment organizations applying no-show reduction strategies in the STAR-SI program did make a significant change from 37% initial no-show rate to 20% postintervention (p = .000). The mean initial no-show rate of 37% is higher than no-show rates, of 2%–30%, typically found in general medicine (Parikh et al., 2010). No-show rates in mental health treatment settings of 33% (Lefforge, Donohue, & Strada, 2007) are similar to the no-show rates in addiction treatment settings found in this trial. Treatment organizations participating in the study made a mean reduction in the no-show rate of 17%. This is similar to the no-show rate reduction of 18.9% reported by Rutkowski et al., (2010) in their California-based NIATx study.

Through the ANOVA analysis, the interventions that had a significant positive impact on no-shows were reducing wait times, using behavioral engagement strategies, and adding capacity. In the medical literature, shorter wait times are associated with fewer missed appointments (Parikh et al., 2010). In this research, reducing waiting times by >10% affected no-show rates. This suggests that treatment organizations seeking to reduce no-shows in the early phases of addiction treatment should focus on strategies to reduce waiting times. Some clinics, in an attempt to eliminate waiting times completely, have replaced prescheduled appointments with walk-in appointments or patient-driven scheduling. Two clinics in this study went to solely walk-in appointments, while another five used a mix of walk-in and scheduled appointments. Systematic review by Rose, Ross, & Horwitz (2011) discovered walk-in scheduling systems tend to be more effective with clinics that have existing no-show rates of >15%.

Another wait-time reduction strategy used in the trial was to schedule more individuals for appointments than there were appointment slots available. A common “overbooking” approach is to book two people for one appointment slot. This strategy assumes no-shows will occur and allows for more patients to be scheduled. An analysis by Berg et al. (2011) found that overbooking reduced no-show rates and had minimal implementation costs.

The practice with the lowest initial no-show rate was creating a welcoming environment with a no-show rate of 28.7%. Creating a welcoming environment was also a significant practice, but had a negative Beta weight. This variable was often implemented in isolation during the study and demonstrated what appears to be an incorrect hope that décor changes alone would have a large impact on no-show rates.

In this study, the use of preappointment reminder calls was the most popular intervention and was applied nearly as frequently as all other interventions combined. Use of reminder calls decreased no-show rates on average by 19%. Twenty of the treatment organizations using reminder calls had changes in no-show rates of ≥20%; however; the 14 treatment organizations that had no-show rate deductions of <10% made this intervention insignificant. Anecdotally, coaches in NIATx projects have found that the interpersonal skills of the person making the calls make a difference, as well as the intake staff’s ability to acquire working phone numbers of clients. These factors should be considered in future investigation of the effectiveness of reminder calls in reducing no-show rates.

Study Limitations

Several limitations existed within this trial. First, the data used in this study were based on data acquired from treatment agencies’ electronic administrative data sets, which can be incorrect (Peabody, Luck, Jain, Bertenthal, & Glassman, 2004). To check for data accuracy, each treatment agency in this project was required to collect a sample of no-show data by comparing the electronic appointment schedule with counselor’s paper documentation (treatment logs). Staff investigated cases where the data did not concur. As a result of these inquiries, several treatment organizations and states modified their data collection and reporting methods, and then made these changes effective retroactive to baseline data collection.

Second, all state and treatment organization participants in four of the ten states were self-selected using non-random sample (Florida, Illinois, Ohio, and Wisconsin). Other states used a self-selection process that resulted in 90+% recruitment of addiction treatment organizations in a targeted geographic area (Iowa, New York, Oklahoma, and South Carolina). Since several of the states and treatment organizations were self-selected, the results should be generalized to state and treatment organization populations that have self-selected to reduce no-show rates.

Third, the study did not employ a comparison group to test the relative effectiveness of the NIATx strategy. The study emphasis was on the intervention strategies that addiction treatment organizations could apply to reduce no-show rates. The NIATx strategy, however, has been demonstrated as being effective in improving a variant of no-show rates: patient continuation in treatment (Mc-Carty et al., 2007; Hoffman, Ford II, Choi, Gustafson, & McCarty, 2008).

CONCLUSIONS

Appointment no-shows present problems to both the patient and the treatment organization. In addiction services, employing process-related interventions that can reduce waiting time for services and increase the capacity for services could be beneficial. Nonprocess improvement changes such as improvements to the physical environment should not be addressed in isolation. This study confirms that behavioral engagement strategies do impact appointment show rates and increase the patient’s therapeutic engagement with the clinician. Future studies should test which strategies have the greatest influence on appointment attendance: environmental conditions, reducing wait times, adding capacity, and or behavioral engagement strategies. If reminder calls are being applied to reduce no-shows, data should be simultaneously collected to measure the effectiveness of this strategy.

The study of no-shows has received considerable attention in general medicine, but limited focus in addiction treatment services. The authors hope that this article will prompt further research on the impact of no-shows on addiction treatment services and the most useful interventions for improving show rates. The ultimate benefit of improved show rates is that patients receive better care, experience successful treatment outcomes, and enjoy a better quality of life.

GLOSSARY

- Appointment No-Show

Term to describe whenever a consumer does not attend a scheduled appointment

- Contingency Management

Practice of rewarding patients’ behaviors for following their treatment plans. For this study, Contingency Management was considered any incentive that was given to a consumer for attending two or more appointments

- Motivational Interviewing

A clinical technique that attempts to capture a consumer’s motivation and apply it to clinical treatment. This practice is described in: Rollnick S. and Miller WR. (1995). What is Motivational Interviewing? Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 23(4): 352–334

- Streamline Admissions

A process to reduce the number of steps in the admission process

- Wait-time (for treatment)

The amount of time that transpires between scheduling a treatment appointment or group is scheduled and when the intake appointment actually occurs

Biography

Todd Molfenter has been involved with leading and studying organizational change theory and practice for the past 20 years. His studies include a systems perspective that investigates the impact that government, management, change leaders, technology, and consumers have on the organizational change process. He is currently studying, through National Institutes on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) grants, how payers influence the adoption of evidence-based practices and organizational preparation for health reform. In his personal time, Todd spends time with his wife and two sons in sports activities, traveling, and camping.

Footnotes

Can be found at www.ers.usda.gov

Declaration of Interest

The author reports no conflict of interest.

References

- Arcury TA, Preisser JS, Gesler WM, Powers JM. Access to transportation and health care utilization in a rural region. The Journal of Rural Health. 2005;21(1):31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg B, Murr M, Chermak D, Woodall J, Pignone M, Sandler RS, et al. Estimating the cost of no-shows and evaluating the effects of mitigation strategies. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0272989X13478194. Retrieved from: http://www.ise.ncsu.edu/bdenton/Papers/pdf/Berg-2011c.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape MA, Katz EC, Stitzer ML. Methods for enhancing transition of substance dependent patients from in-patient to outpatient treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;61(2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HW. SAAS National Conference and NIATx Summit. Cincinnati, OH: Keynote speech; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Craig RJ, Olson RE. Predicting methadone maintenance treatment outcomes using the Addiction Severity Index and the MMPI-2 Content Scales (negative treatment indicators and cynism scales) The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(4):823–839. doi: 10.1081/ada-200037548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger DS, Lamb RJ, Marlowe DB, Kirby KC. From telephone to office: Intake attendance as a function of appointment delay. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27(1):131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KA, Ford JH, II, Choi D, Gustafson DH, McCarty D. Replication and sustainability of improved access and retention within the Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;98(1–2):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KR, Booth PG, Salmon P, McGuire J. The effects of telephone prompting on attendance for starting treatment and retention in treatment at a specialist alcohol clinic. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;48(4):437–442. doi: 10.1348/014466509X457469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy NL, Paulman A, Reuter MD, Lovejoy B. Why we don’t come: Patient perceptions on no-shows. Annals of Family Medicine. 2004;2(6):541–545. doi: 10.1370/afm.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser KE, Mintzer IL, Lambert A, Cabral H, Bor DH. Missed appointment rates in primary care: The importance of site of care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2005;16(3):475–486. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefforge NL, Donohue B, Strada MJ. Improving session attendance in mental health and substance abuse settings: A review of controlled studies. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38(1):1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh G, Ogborne AC, Cleland P. Factors associated with patient dropout from an outpatient alcoholism treatment service. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1984;45(4):359–362. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1984.45.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell S, Maljanian R, Horowitz S, Pianka MA, Cabrera Y, Greene J. Effectiveness of reminder systems on appointment adherence rates. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2001;12(4):504–514. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Chandler RK. Understanding the importance of organizational and system variables on addiction treatment services within criminal justice settings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103(Suppl 1):S91–S93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Gustafson DH, Wisdom JP, Ford J, Choi D, Molfenter T, et al. The network for the improvement of addiction treatment (NIATx): Enhancing access and retention. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(2–3):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist. 2009;64(6):527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. A comparative survey of missed initial and follow-up appointments to psychiatric specialties in the United Kingdom. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(6):868–871. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh A, Gupta K, Wilson AC, Fields K, Cosgrove NM, Kostis JB. The effectiveness of outpatient appointment reminder systems in reducing no-show rates. The American Journal of Medicine. 2010;123(6):542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody JW, Luck J, Jain S, Bertenthal D, Glassman P. Assessing the accuracy of administrative data in health information systems. Medical Care. 2004;42(11):1066–1072. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101(11):1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Huber A, Sodano R, Chudzynski JE, Moynier E, Shoptaw S. A comparison of five reinforcement schedules for use of contingency management-based treatment of methamphetamine abuse. The Psychological Record. 2006;56(1):67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa M, Scripa JS, Zastowny TR, Ford JH., II Using a NIATx based local learning collaborative for performance improvement. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2011;34(4):390–398. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose KD, Ross JS, Horwitz LI. Advanced access scheduling outcomes: A systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(13):1150–1159. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JP, Kula TJ, Jr, Glanos A, Kula K. Effect of a computer-generated telephone reminder system on appointment attendance. Seminars in Orthodontics. 2004;10(3):190–193. [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski BA, Gallon S, Rawson RA, Freese TE, Bruehl A, Crevecoeur-MacPhail D, et al. Improving client engagement and retention in treatment: The Los Angeles County experience. Journal of Substance Abuse and Treatment. 2010;39(1):78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears C, Davis T, Guydish J, Gleghorn A. Investigating the effects of San Francisco’s treatment on demand initiative on a publicly-funded substance abuse treatment system: A time series analysis. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2009;41(3):297–304. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2009.10400540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone CA, Palmer JH, Saxby PJ, Devaraj VS. Reducing non-attendance at outpatient clinics. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1999;92(3):114–118. doi: 10.1177/014107689909200304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CY, Wang MC, Liao WT, Lu JH, Sun PH, Lin BYJ, et al. Hospital outpatient perceptions of the physical environment of waiting areas: The role of patient characteristics on atmospherics in one academic medical center. BMC Health Services Research. 2007;7:198. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Mertens J, Tam T, Moore C. Factors affecting the initiation of substance abuse treatment in managed care. Addiction. 2001;96(5):705–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9657056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ME, Latta J, Conversano P. Eliminating the wait for mental health services. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2008;35(1):107–114. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]