Abstract

During mouse development, imprinted X chromosome inactivation (XCI) is observed in preimplantation embryos and is inherited to the placental lineage, whereas random XCI is initiated in the embryonic proper. Xist RNA, which triggers XCI, is expressed ectopically in cloned embryos produced by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). To understand these mechanisms, we undertook a large-scale nuclear transfer study using different donor cells throughout the life cycle. The Xist expression patterns in the reconstructed embryos suggested that the nature of imprinted XCI is the maternal Xist-repressing imprint established at the last stage of oogenesis. Contrary to the prevailing model, this maternal imprint is erased in both the embryonic and extraembryonic lineages. The lack of the Xist-repressing imprint in the postimplantation somatic cells clearly explains how the SCNT embryos undergo ectopic Xist expression. Our data provide a comprehensive view of the XCI cycle in mice, which is essential information for future investigations of XCI mechanisms.

Keywords: X chromosome inactivation, mouse, nuclear transfer, embryo

Introduction

During mouse development, 2 types of X chromosome inactivation (XCI) in female cells ensure the silencing of one of the two X chromosomes in a stage-specific manner. Imprinted XCI, which preferentially inactivates the paternal X, is maintained through the preimplantation stage and is inherited in the placental tissues.1 By contrast, another type of XCI, the so-called random XCI, occurs in cells of the embryo proper after implantation and persists throughout life.2 Both forms of XCI are triggered by Xist, a noncoding RNA that acts on the future inactivated X chromosome in cis.3 Despite this commonality, there is increasing evidence that the mechanisms of initiation and maintenance of these 2 types of XCI are very different. Random XCI involves complicated networks of multiple XCI factors, which often act in a redundant, dose-dependent manner. The Tsix and Xite genes, for example, are specifically involved in random XCI as repressors of XCI.4 Furthermore, there is a series of complex mechanisms for tuning the X-dosage before establishment of random XCI; “pairing,” “counting,” and “choice.”5 Until now, the molecules and underlying mechanisms for random XCI have been studied in depth using systems for the in vitro differentiation of female embryonic stem (ES) cells in mice and humans.6 In contrast to the abundant information on random XCI, the nature and origin of imprinted XCI have yet to be identified despite the distinct Xist expression pattern in preimplantation embryos and cells of the placental lineage. Furthermore, there are conflicting scenarios for the imprinted XCI: the imprint could be of maternal or paternal origin, or both.

Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) is a technique to introduce a somatic cell nucleus into an enucleated oocyte, which can then develop into an embryo and—very inefficiently—into a cloned offspring.7 In mice, analysis of female SCNT-derived embryos for the Xist expression pattern and XCI-specific markers have shown that both X chromosomes were inactivated by ectopic Xist expression.8-10 It has also been reported that Xist is expressed from only the X chromosome in male SCNT embryos.10 Intriguingly, this SCNT-associated perturbation is autonomously corrected after implantation in both embryonic and extraembryonic lineages of both sexes.11,12 A series of experiments using gene knockout and knockdown strategies demonstrated that this ectopic expression of Xist critically affected the development of SCNT embryos because deletion or downregulation of Xist resulted in about a 10-fold increase in the birth rates of cloned offspring.10,11 However, we still do not know why Xist is ectopically expressed in SCNT embryos or how it normalizes its expression after implantation.

This study was undertaken to obtain clues for understanding the mechanisms underlying the cycle of XCI and its SCNT-associated perturbation. We performed a large-scale nuclear transfer (NT) study using different donor cell types throughout the life cycle and examined which genomes repressed or allowed the expression of Xist in the reconstructed embryos.

Results

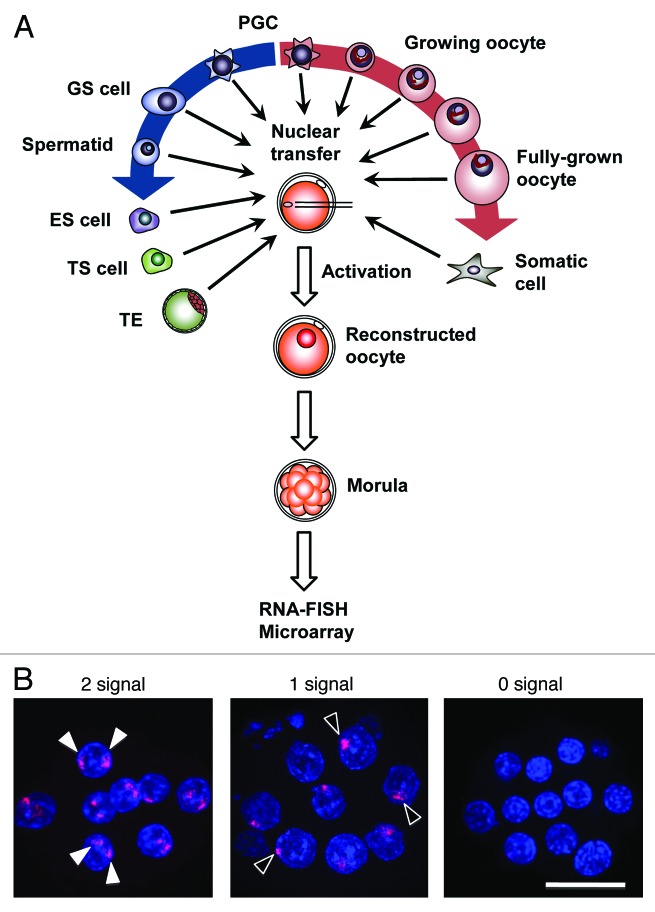

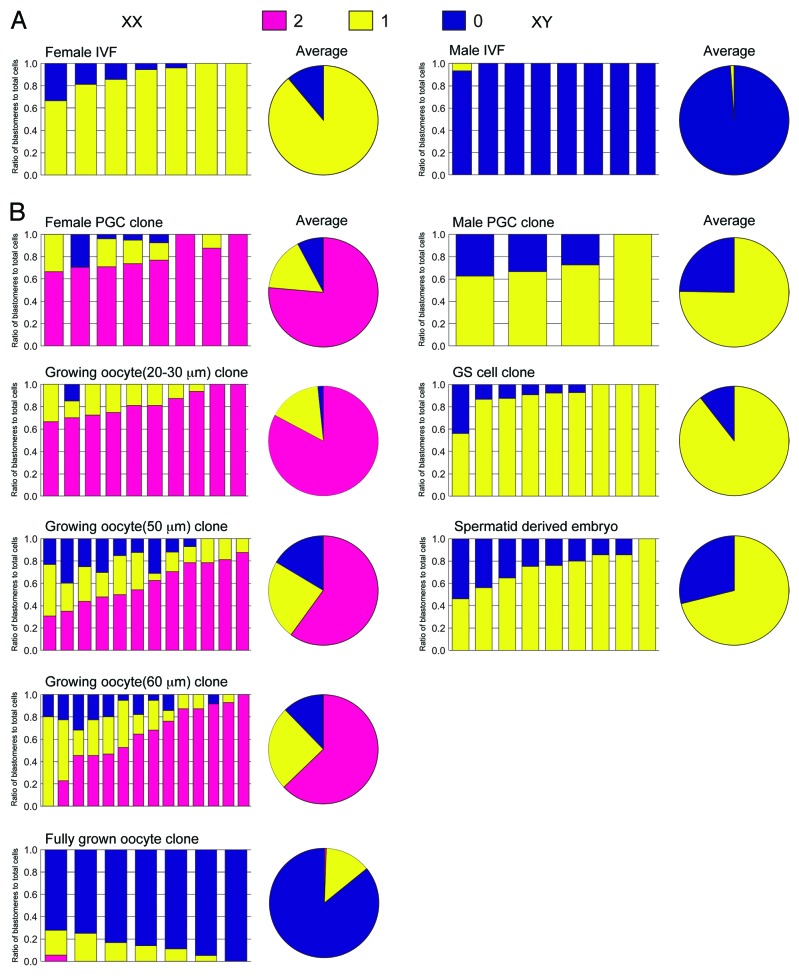

Embryos were reconstructed by NT using different donor cells: primordial germ cells (PGCs) at embryonic day 12.5 (female and male), spermatogonial stem cells (germline stem [GS] cells) (male), spermatids (male), oocytes (20–80 μm diameter, female), ES cells (female and male), trophoblast stem (TS) cells (female and male), trophectoderm (TE) cells of blastocysts (female and male), and somatic cells (cumulus cells and immature Sertoli cells) (Fig. 1A). We evaluated the number of Xist RNA signals in each blastomere by RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNA–FISH) at the morula stage (Fig. 1B). Embryos derived from in vitro fertilization (IVF) were used as controls. About half (7/15) of the IVF embryos consistently showed a single signal in each blastomere and the remaining embryos (8/15) showed no signal, probably representing female and male embryos, respectively (Fig. 2A). In embryos reconstructed with PGC nuclei (PGC embryos), most blastomeres showed Xist RNA signals according to the number of X chromosomes: 1 signal from the XY PGC embryos and 2 signals from the XX PGC embryos, indicating that Xist was expressed from all of the existing alleles (Fig. 2B). Similarly, in XY embryos reconstructed from GS cells or spermatids, most blastomeres showed a single Xist RNA signal (Figs. 1B and 2B). In XX embryos from nongrowing (20–30 μm) or middle-sized growing oocytes (50–60 μm), blastomeres predominantly showed 2 Xist signals, indicating that Xist could also be expressed from these oocyte genomes (Figs. 1B and 2B). However, when embryos were reconstructed from fully grown oocytes (70–80 μm), Xist was completely repressed in most blastomeres (86%; Figs. 1B and 2B; Fig. S1). Thus, all genomes from all the germ cell types, with the exception of mature oocytes, allowed Xist to be expressed at the morula stage (Fig. S1). These observations suggest that Xist expression can only be repressed by some maternal imprint established at the very last stage of oogenesis.

Figure 1. Experimental scheme. (A) Embryos were reconstructed by NT using different donor cell types throughout the life cycle to determine which genomes repressed or allowed the expression of Xist as analyzed by RNA–FISH. (B) Representative images of embryos from left to right: embryo derived from a nongrowing oocyte (20 μm diameter; XX, 2 signals per blastomere); embryo from a GS cell (XY, one signal per blastomere); and embryo from a fully grown oocyte (80 μm; XX, no signal). (Scale bar = 50 μm).

Figure 2. RNA–FISH analysis of Xist in morula embryos reconstructed with nuclei from different types of germ cells. The nuclei of different germ cells were transferred into enucleated oocytes and then the reconstructed embryos were analyzed by RNA–FISH for Xist. The ratio of blastomeres classified according to the number of Xist signals is shown. Each bar in the charts represents a single embryo. The pie charts show the average distributions of blastomeres having 0, 1, or 2 Xist signals. Blastomeres at metaphase (fewer than 10%) were omitted from the data. (A) Embryos derived from IVF. Female and male embryos showed predominantly a single signal and no signal, respectively. The data on female embryos is from Oikawa et al.12 (B) Embryos derived from female germ cells (left column, XX) showed predominantly 2 Xist signals, except for those from fully grown oocytes that showed no signal in the majority of blastomeres. Embryos derived from male germ cells (right column, XY) showed a single Xist signal in most blastomeres. These findings indicate that the Xist-repressing imprint is established at the final stage of oogenesis. The exact ratios of the Xist signal patterns are listed in Figure S1.

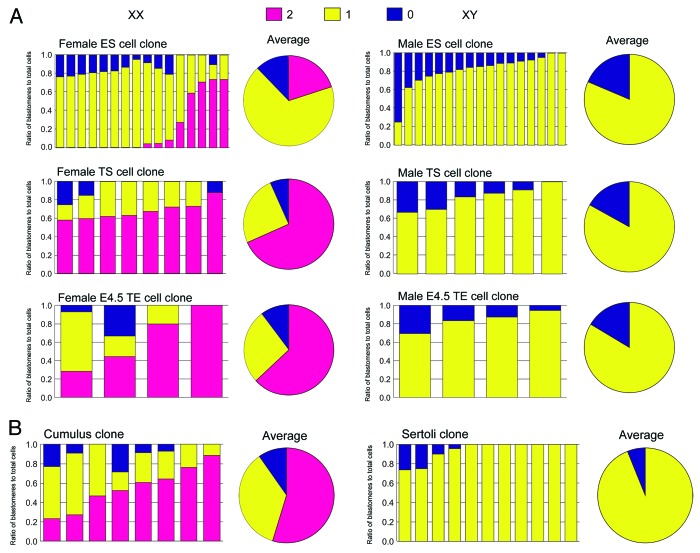

The maternal Xist imprint is maintained after fertilization, as revealed by consistent Xist repression in the putative maternal allele in fertilized embryos.13 Shortly before implantation, the imprinted XCI is thought to be terminated in cells of the inner cell mass (ICM), but not in cells of the TE, as expected from the corresponding XCI pattern reported.1,13 Consistent with this finding, in NT embryos derived from female and male ES cells—derivatives of the ICM—Xist was expressed from all of the existing alleles, although those derived from female ES cells often showed a predominant single-signal pattern for unknown reasons (Fig. 3A). However, NT embryos derived from TS cells—derivatives of the TE—unexpectedly also showed ectopic Xist expression similar to that seen in somatic cell-derived embryos in both sexes (cumulus clone and Sertoli clone) (Fig. 3). These results indicate that the maternal Xist imprint was erased in both extraembryonic and embryonic lineages. In the ICM, reactivation of the paternal X (corresponding to the end of imprinted XCI) is reported to occur at the late blastocyst stage.13 To determine whether this is also true for the TE, we examined Xist expression in embryos reconstructed with TE nuclei from late blastocysts (at embryonic day 4.5). The Xist-repressing imprint had been erased in the TE at the late blastocyst stage, as in the ICM of the same stage (Fig. 3A). We further confirmed the erasure of the Xist imprint in the extraembryonic lineages by ectopic upregulation of Xist in embryos cloned from extraembryonic ectoderm cells at embryonic day 6.5, or from TS cells (Fig. S2). Embryos reconstructed with nuclei from cumulus cells and immature Sertoli cells—representing female and male SCNT embryos, respectively—also showed ectopic Xist expression as described previously (Fig. 3B).10

Figure 3. RNA–FISH analysis of Xist in morula embryos reconstructed with nuclei from different peri- and postimplantation cells. See also the legend for Figure 2. (A) Embryos derived from ES cells or TS cells showed reappearance of Xist expression, indicating that the maternal Xist-repressing imprint had been erased in both embryonic and extraembryonic lineages. This erasure was observed in the TE as early as embryonic day 4.5 (late blastocyst stage). Embryos reconstructed with cumulus cells and immature Sertoli cells, representing female and male SCNT embryos, respectively, also showed ectopic Xist expression as reported previously.10 Exceptionally, female embryos derived from ES cells often showed a predominant single-signal pattern (predominantly yellow) for unknown reasons. (B) Embryos derived from cumulus cells and Sertoli cells. Some of the data on Sertoli cell clones are from Inoue et al.10 and Matoba et al.11 The exact ratios of the Xist signal patterns are listed in Figure S1.

To ensure the preciseness of the results from the female donor cells of the in vitro origin (ES cells and TS cells), we undertook chromosomal analysis for these cell lines. Both cell lines showed normal ploidy (2n = 40) and 2 X chromosomes (Fig. S3).

Discussion

Our large-scale NT study demonstrated that, among the genomes of different donor cells selected throughout the life cycle, only the genome of fully grown oocytes could repress the expression of Xist at the morula stage. This shows equivocally that expression of Xist by zygotic gene activation is its default mode and that this Xist expression can be repressed only by some maternal imprint established at the very last stage of oogenesis. The presence of the maternal imprint was first hypothesized by the observation that the X chromosome from a nongrowing oocyte, but not from a fully grown oocyte, became inactive in the extraembryonic tissue.14 The paternal origin hypothesis represents the “preinactivation model.” It depends on the precocious silencing of some paternal X-linked genes, which is thought to be the consequence of heterochromatinization during meiotic sex chromosome inactivation (MSCI) in the testes.15 Otherwise, imprinted XCI might comprise an initial phase of silencing through MSCI and a subsequent Xist-dependent phase in the zygote.16 Our NT study suggests that there is primarily a strict maternal imprint dependency of imprinted XCI and preinactivation of paternal X-linked genes seems to be dispensable.

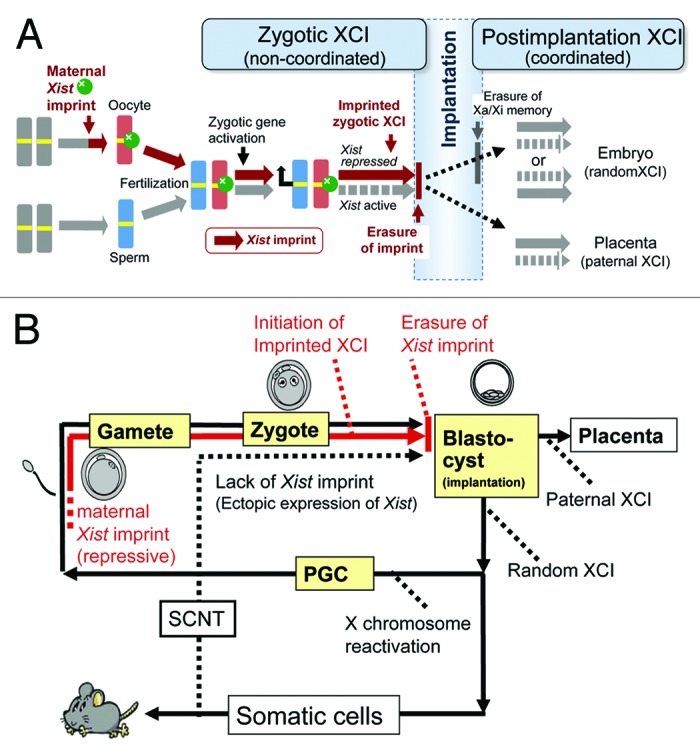

The maternal origin hypothesis mentioned above depended on differential XCI patterns (e.g., marker gene expression on the active X chromosome) of the extraembryonic tissues derived from nongrowing and fully grown oocytes.14 The present study provides the first direct evidence for this maternal Xist-repressing imprint by detecting the deposition of the Xist RNA in the nucleus of preimplantation embryos (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, our findings confine the establishment of the Xist imprint to a narrow window at the last stage of oogenesis at around 70–80 μm diameter in the mouse. The autosomal imprint of maternally imprinted genes is known to be established during oogenesis in an oocyte size-dependent manner.17,18 Although the oocytes from adult female mice showed a slightly slower progression of imprinting than did those in juvenile female mice, the maternal imprint of autosomal imprinted genes was imposed in growing oocytes at sizes between 55 μm and 70 μm.18 Therefore, our findings here imply that the Xist imprint, which is preceded by the maternal autosomal imprinting, is established rapidly while the oocytes are reaching their maximal sizes.

Figure 4. XCI cycle in mice. (A) Two phases of XCI before and after implantation. Our large-scale NT experiments revealed that imprinted XCI in mice is under the strict control of the maternal Xist-repressing imprint established at the last stage of oogenesis (brown). This imprint was erased from both embryonic and extraembryonic (placental) lineages at implantation. Therefore, the preferential inactivation of the paternal X in the placental lineage is not an imprinted XCI in a strict sense. These 2 postimplantation lineages show random or paternal XCI, probably depending on the persistence of the active/inactive (Xa/Xi) memories of earlier blastomere cells (see Discussion). The XCI regulation may be shifted from preimplantation (zygotic) control to postimplantation control at implantation. The latter likely plays a role in the more refined tuning of the X chromosome dosage. (B) X chromosome inactivation cycle and SCNT. The Xist-repressing imprint is established during oogenesis and is inherited by fertilized embryos (red line). The imprint is erased before implantation and remains in neither the embryonic proper nor the placental lineage (see A). The cells in the embryonic lineage undergo random inactivation and are devoid of the imprint. Therefore, after SCNT, ectopic Xist expression occurs in the putative active X in cloned embryos of both sexes.8-10

Until now, the molecular mechanism of imprinted XCI has been unclear. Unlike genomic imprinting, it was reported that the Xist-repressing imprint is independent of DNA methylation, as revealed by the onset of imprinted XCI in fertilized embryos without maternal DNA methyltransferases, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b.19 However, we found that parthenogenetic embryos derived from the same double-knockout oocytes showed moderate Xist expression at the morula stage (Oikawa et al., unpublished data). This may imply that DNA methylation is involved, at least in part, in the repression of Xist in preimplantation embryos and that this might be compensated by some paternally derived factors after zygotic gene activation. Tsix, the antisense counterpart of Xist, does not account for imprinted XCI because it is not expressed until the morula/blastocyst stage, a few days after initiation of imprinted XCI.20,21 Identification of the molecular mechanism of imprinted XCI is essential for confirming the complete erasure of the Xist-repressing imprint in both embryonic and extraembryonic lineages (see below).

We have found recently that Xist is expressed ectopically from the active X chromosomes in SCNT embryos and is then corrected autonomously after implantation.10-12 The timing of the establishment/erasure of the Xist imprint and the strict maternal imprint dependency of imprinted XCI presented here might provide a compelling explanation for these SCNT-specific Xist expression patterns. Somatic cells are postimplantation cells and should therefore be devoid of the Xist imprint. This is why the Xist is ectopically expressed in SCNT embryos of both sexes before implantation (Fig. 4B). Exceptionally, embryos cloned from female ES cells often showed a normal single-signal pattern (Fig. 3A). Although the underlying mechanism is unclear, perhaps some X-chromosome counting mechanism worked in these embryos, as seen in XX androgenetic embryos.22 The autonomous correction of Xist expression in postimplantation SCNT embryos might be explained by the reprogramming of XCI regulation during implantation, as discussed below. Intriguingly, SCNT embryos also showed Xist-independent correction of gene expression profiles, indicating the presence of extensive reprogramming of the genomic state during implantation.23

This NT study has demonstrated that, in mouse embryos, the maternal Xist-repressing imprint is also erased in placental tissues, specifically before day 4.5. Therefore, in a strict sense, the preferential inactivation of the paternal X chromosome in the mouse placentas is not imprinted but may be “biased” or “skewed” (Fig. 4A). It is likely that the X chromosomes of the extraembryonic cells have taken over the active/inactive memories of the parental X chromosome, as do other female cells, independent of the maternal imprint. This assumption is supported by a study reporting the occasional inactivation of the maternal X chromosome in extraembryonic tissues with a paternal Xist deletion.24 By contrast, the parental active/inactive memories are erased completely in the epiblast, leading to random XCI in the embryonic lineage. This has been confirmed experimentally by the occurrence of random XCI in trophoblastic cells that differentiated from female ES cells in vitro.25 Therefore, it is reasonable to consider that XCI regulation shifts systemically from the initial zygotic machinery to the secondary postimplantation regulation.

In this study, we took advantage of NT in the study of epigenetics. In theory, the imprints imposed during gametogenesis are not reprogrammed by NT because they are normally unchanged after fertilization and are inherited by the fertilized embryo. Therefore, it is expected that these reprogramming-resistant memories are carried over to the cloned embryos and that their biological and functional aspects can be analyzed at defined developmental stages. These memories typically include autosomal genomic imprinting that ensures parent-of-origin-specific gene expression,26 and its erasure process during PGC development has been documented comprehensively using NT.27 It is also the case with the Xist imprint analyzed in this study. NT using donor cells throughout the life cycle revealed a more complete picture of the XCI cycle in mice and clearly accounted for unexplained ectopic Xist expression in SCNT embryos (Fig. 4B). We expect that the precisely identified timings of the XCI transitions may provide the fundamental basis for the study of the molecular mechanisms underlying XCI regulation, including those governing the establishment and erasure of the maternal imprint and the reprogramming of the XCI control at implantation.

Materials and Methods

Animals

B6D2F1 (C57BL/6 × DBA/2 hybrid) female mice were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan) and used as donors for oocytes and donor cells. Some donor cells with the same B6D2F1 genetic background were prepared by mating C57BL/6 females with DBA/2 males in our laboratory. The animals were housed under a controlled lighting condition (daily light 07:00–21:00 h) and were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee at the RIKEN Tsukuba Institute and were performed in accordance with the committee’s guiding principles.

Preparation of donor cells

Primordial germ cells as nuclear donors were collected from the gonads of day 12.5 fetuses shortly before NT. Two or 3 fetal gonads were placed in HEPES-buffered potassium simplex optimized medium (KSOM) containing 10% polyvinylpyrrolidone in a micromanipulation chamber and punctured using a fine needle to allow the PGCs to spread into the medium, as described previously.27 Germline stem cells established from neonatal B6D2F1 male mice were a gift from Dr. Takashi Shinohara. These cells were cultured as described previously.28 TS cells were established from a B6 male embryo and were cultured as described previously.29 To obtain extraembryonic ectoderm cells, embryos at the two-cell stage were transferred into the oviducts of ICR strain recipient mice (CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan) on day 1 of pseudopregnancy (induced by mating with a vasectomized male mouse). On embryonic day 6.5, the recipients were sacrificed and the implanted embryos were carefully recovered from the uteri. Extraembryonic ectoderm was isolated using fine forceps and punctured in HEPES-buffered KSOM containing 10% polyvinylpyrrolidone, as described above. Immature Sertoli cells were collected from 3- to 7-d-old male neonates. The cells were prepared as described previously.30 Briefly, the collected testicular cells were treated with 0.1 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.01 mg/ml deoxyribonuclease (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by 0.2 mg/ml trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min at 37 °C. The testicular cell suspension was washed with Ca2+/Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 4 mg/ml bovine serum albumin and were used for injection. Cumulus cells were collected from cumulus–oocyte complexes after treatment with KSOM containing 0.1% bovine testicular hyaluronidase (Calbiochem).

NT

NT was conducted as described previously.31,32 Recipient oocytes were collected from B6D2F1 strain female mice following superovulation and enucleated in HEPES-buffered KSOM containing 7.5 μg/ml cytochalasin B (Calbiochem). Thereafter, the donor cell nuclei were injected into enucleated oocytes using a piezo-driven micromanipulator (PMM-150FU; Prime Tech). After culture in KSOM at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air for 1 h, the injected oocytes were activated in Ca2+-free KSOM containing 2.5 mM SrCl2. The reconstructed embryos were cultured in KSOM containing 5 μg/ml cytochalasin B for 5 h. Finally, embryos were cultured in KSOM containing 50 nM trichostatin A (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h. After washing, the embryos were cultured in KSOM until analysis.

Production of spermatid-derived embryos

Production of spermatid-derived (androgenetic) embryos was conducted as described previously.33 Round spermatids were isolated mechanically from the testes of mature male mice. The cell suspension was washed by centrifugation and stored in GL-PBS medium.34 Oocytes at meiosis II (MII) were preactivated in Ca2+-free KSOM containing 2.5 mM SrCl2 for 20 min. Two spermatid nuclei were injected into individual oocytes advancing to telophase II in HEPES-buffered KSOM at around 40–70 min after oocyte activation. The female nucleus was removed, together with the second polar body, within 4 h after oocyte activation in the presence of cytochalasin B.

Production of embryos reconstructed from oocytes by serial NT

To produce embryos from oocytes at different growth stages, follicular oocytes were collected from the ovaries of adult, 2-, 12-, and 20-d-old mice as described previously.18 After collection, the diameter of the oocytes was measured using an inverted microscope and a calibrated eyepiece graticule scale. Embryos were reconstructed by serial NT.35 Briefly, karyoplasts obtained from the growing oocytes were fused with fully grown enucleated germinal vesicle (GV)-stage oocytes using HVJ-E (GenomeONE-CF). The reconstructed oocytes were matured in TaM (1:1 mixture of α-MEM and TYH) as described previously.36 After 16–18 h, MII chromosomes of in vitro-matured oocytes were transferred to the enucleated, fresh MII oocytes. About 1 h later, they were activated with SrCl2 in the presence of cytochalasin B as described above.

RNA–FISH

RNA–FISH was conducted as described previously.10-12 A probe to detect Xist RNA labeled with Cy3-dCTP by random-primed reverse transcription from in vivo transcribed Xist RNA. Embryos were incubated in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 s on ice and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Hybridization was conducted at 37 °C overnight. The nuclei of embryos were stained with DAPI. Xist signals were observed using a confocal scanning laser microscope (Digital Eclipse C1; Nikon Instruments).

RNA amplification and microarray analysis (Fig. S2)

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) from single blastocysts cultured for 96 h. The RNA was then subjected to 2 rounds of linear amplification using TargetAmp Two-Round Aminoallyl-aRNA Amplification Kits (Epicenter) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For control embryos, single blastocysts generated by IVF37 were subjected to total RNA extraction and 2 rounds of RNA amplification. Amplified RNA was labeled with Cy3 dye (GE Healthcare) and hybridized to a whole mouse genome oligo DNA microarray (4 × 44K; Agilent Technologies) for 16 h at 65 °C according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The scanned images of microarray slides were processed using Feature Extraction software (Agilent Technologies). All raw data were loaded into GeneSpring GX 12 (Agilent Technologies) and transformed by quantile normalization.

Chromosome analysis

ES and TS cells in culture dishes were treated with 25 ng/ml Colcemid for 30 min, and the round cells composed mostly of cells in metaphase were collected, spread onto clean glass slides, allowed to dry in air, and stained with DAPI. Metaphase images were observed under a fluorescent microscope (Axio Photo 2; Carl Zeiss), and karyotype analysis was performed using an Ikaros karyotyping system (Carl Zeiss).

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Mito Kanatsu-Shinohara and Dr Takashi Shinohara for kindly providing the GS cells. We also thank Dr Hitoshi Hiura and Dr Takahiro Arima for their technical advice on the collection of growing oocytes. This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan to Ogura A and Inoue K.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- ICM

inner cell mass

- SCNT

somatic cell nuclear transfer

- TE

trophectoderm

- XCI

X chromosome inactivation

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials may be found here:

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/epigenetics/article/26939

References

- 1.Takagi N, Sasaki M. Preferential inactivation of the paternally derived X chromosome in the extraembryonic membranes of the mouse. Nature. 1975;256:640–2. doi: 10.1038/256640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyon MF. Gene action in the X-chromosome of the mouse (Mus musculus L.) Nature. 1961;190:372–3. doi: 10.1038/190372a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Augui S, Nora EP, Heard E. Regulation of X-chromosome inactivation by the X-inactivation centre. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:429–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JT. Gracefully ageing at 50, X-chromosome inactivation becomes a paradigm for RNA and chromatin control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:815–26. doi: 10.1038/nrm3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masui O, Bonnet I, Le Baccon P, Brito I, Pollex T, Murphy N, Hupé P, Barillot E, Belmont AS, Heard E. Live-cell chromosome dynamics and outcome of X chromosome pairing events during ES cell differentiation. Cell. 2011;145:447–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bermejo-Alvarez P, Ramos-Ibeas P, Gutierrez-Adan A. Solving the “X” in embryos and stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:1215–24. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogura A, Inoue K, Wakayama T. Recent advancements in cloning by somatic cell nuclear transfer. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20110329. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bao S, Miyoshi N, Okamoto I, Jenuwein T, Heard E, Azim Surani M. Initiation of epigenetic reprogramming of the X chromosome in somatic nuclei transplanted to a mouse oocyte. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:748–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nolen LD, Gao S, Han Z, Mann MR, Gie Chung Y, Otte AP, Bartolomei MS, Latham KE. X chromosome reactivation and regulation in cloned embryos. Dev Biol. 2005;279:525–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue K, Kohda T, Sugimoto M, Sado T, Ogonuki N, Matoba S, Shiura H, Ikeda R, Mochida K, Fujii T, et al. Impeding Xist expression from the active X chromosome improves mouse somatic cell nuclear transfer. Science. 2010;330:496–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1194174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matoba S, Inoue K, Kohda T, Sugimoto M, Mizutani E, Ogonuki N, Nakamura T, Abe K, Nakano T, Ishino F, et al. RNAi-mediated knockdown of Xist can rescue the impaired postimplantation development of cloned mouse embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20621–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112664108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oikawa M, Matoba S, Inoue K, Kamimura S, Hirose M, Ogonuki N, Shiura H, Sugimoto M, Abe K, Ishino F, et al. RNAi-mediated knockdown of Xist does not rescue the impaired development of female cloned mouse embryos. J Reprod Dev. 2013;59:231–7. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2012-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okamoto I, Otte AP, Allis CD, Reinberg D, Heard E. Epigenetic dynamics of imprinted X inactivation during early mouse development. Science. 2004;303:644–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1092727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tada T, Obata Y, Tada M, Goto Y, Nakatsuji N, Tan S, Kono T, Takagi N. Imprint switching for non-random X-chromosome inactivation during mouse oocyte growth. Development. 2000;127:3101–5. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huynh KD, Lee JT. Inheritance of a pre-inactivated paternal X chromosome in early mouse embryos. Nature. 2003;426:857–62. doi: 10.1038/nature02222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huynh KD, Lee JT. A continuity of X-chromosome silence from gamete to zygote. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2004;69:103–12. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obata Y, Kono T. Maternal primary imprinting is established at a specific time for each gene throughout oocyte growth. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5285–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiura H, Obata Y, Komiyama J, Shirai M, Kono T. Oocyte growth-dependent progression of maternal imprinting in mice. Genes Cells. 2006;11:353–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiba H, Hirasawa R, Kaneda M, Amakawa Y, Li E, Sado T, Sasaki H. De novo DNA methylation independent establishment of maternal imprint on X chromosome in mouse oocytes. Genesis. 2008;46:768–74. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sado T, Wang Z, Sasaki H, Li E. Regulation of imprinted X-chromosome inactivation in mice by Tsix. Development. 2001;128:1275–86. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sado T, Ferguson-Smith AC. Imprinted X inactivation and reprogramming in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(suppl_1):R59–64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto I, Tan S, Takagi N. X-chromosome inactivation in XX androgenetic mouse embryos surviving implantation. Development. 2000;127:4137–45. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirasawa R, Matoba S, Inoue K, Ogura A. Somatic donor cell type correlates with embryonic, but not extra-embryonic, gene expression in postimplantation cloned embryos. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mugford JW, Yee D, Magnuson T. Failure of extra-embryonic progenitor maintenance in the absence of dosage compensation. Development. 2012;139:2130–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.076497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murakami K, Araki K, Ohtsuka S, Wakayama T, Niwa H. Choice of random rather than imprinted X inactivation in female embryonic stem cell-derived extra-embryonic cells. Development. 2011;138:197–202. doi: 10.1242/dev.056606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inoue K, Kohda T, Lee J, Ogonuki N, Mochida K, Noguchi Y, Tanemura K, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ishino F, Ogura A. Faithful expression of imprinted genes in cloned mice. Science. 2002;295:297. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5553.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, Inoue K, Ono R, Ogonuki N, Kohda T, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ogura A, Ishino F. Erasing genomic imprinting memory in mouse clone embryos produced from day 11.5 primordial germ cells. Development. 2002;129:1807–17. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Miki H, Ogura A, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. Long-term proliferation in culture and germline transmission of mouse male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:612–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka S, Kunath T, Hadjantonakis AK, Nagy A, Rossant J. Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4. Science. 1998;282:2072–5. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogura A, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Noguchi A, Takano K, Nagano R, Suzuki O, Lee J, Ishino F, Matsuda J. Production of male cloned mice from fresh, cultured, and cryopreserved immature Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:1579–84. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wakayama T, Perry AC, Zuccotti M, Johnson KR, Yanagimachi R. Full-term development of mice from enucleated oocytes injected with cumulus cell nuclei. Nature. 1998;394:369–74. doi: 10.1038/28615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Mochida K, Yamamoto Y, Takano K, Kohda T, Ishino F, Ogura A. Effects of donor cell type and genotype on the efficiency of mouse somatic cell cloning. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1394–400. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miki H, Hirose M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Kezuka F, Honda A, Mekada K, Hanaki K, Iwafune H, Yoshiki A, et al. Efficient production of androgenetic embryos by round spermatid injection. Genesis. 2009;47:155–60. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogura A, Yanagimachi R. Round spermatid nuclei injected into hamster oocytes from pronuclei and participate in syngamy. Biol Reprod. 1993;48:219–25. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Obata Y, Maeda Y, Hatada I, Kono T. Long-term effects of in vitro growth of mouse oocytes on their maturation and development. J Reprod Dev. 2007;53:1183–90. doi: 10.1262/jrd.19079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miki H, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Baba T, Ogura A. Improvement of cumulus-free oocyte maturation in vitro and its application to microinsemination with primary spermatocytes in mice. J Reprod Dev. 2006;52:239–48. doi: 10.1262/jrd.17078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mochida K, Ohkawa M, Inoue K, Valdez DM, Jr., Kasai M, Ogura A. Birth of mice after in vitro fertilization using C57BL/6 sperm transported within epididymides at refrigerated temperatures. Theriogenology. 2005;64:135–43. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.