Abstract

Summary

We systematically reviewed the literature on the performance of osteoporosis absolute fracture risk assessment instruments. Relatively few studies have evaluated the calibration of instruments in populations separate from their development cohorts, and findings are mixed. Many studies had methodological limitations making susceptibility to bias a concern.

Introduction

The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature on the performance of osteoporosis clinical fracture risk assessment instruments for predicting absolute fracture risk, or calibration, in populations other than their derivation cohorts.

Methods

We performed a systematic review, and MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, and multiple other literature sources were searched. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied and data extracted, including information about study participants, study design, potential sources of bias, and predicted and observed fracture probabilities.

Results

A total of 19,949 unique records were identified for review. Fourteen studies met inclusion criteria. There was substantial heterogeneity among included studies. Six studies assessed the WHO's Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) instrument in five separate cohorts, and a variety of risk assessment instruments were evaluated in the remainder of the studies. Approximately half found good instrument calibration, with observed fracture probabilities being close to predicted probabilities for different risk categories. Studies that assessed the calibration of FRAX found mixed performance in different populations. A similar proportion of studies that evaluated simple risk assessment instruments (≤5 variables) found good calibration when compared with studies that assessed complex instruments (>5 variables). Many studies had methodological features making them susceptible to bias.

Conclusions

Few studies have evaluated the performance or calibration of osteoporosis fracture risk assessment instruments in populations separate from their development cohorts. Findings are mixed, and many studies had methodological limitations making susceptibility to bias a possibility, raising concerns about use of these tools outside of the original derivation cohorts. Further studies are needed to assess the calibration of instruments in different populations prior to widespread use.

Keywords: Calibration, Fracture, Osteoporosis, Risk assessment, Systematic review

Introduction

Osteoporosis is estimated to affect 200 million people worldwide and the morbidity, mortality, and costs associated with osteoporotic fractures are substantial [1–4]. Treatment of individuals at increased risk for osteoporotic fracture can reduce fracture risk and improve health outcomes; however, most individuals with osteoporosis are unidentified and untreated [5–7]. Many national clinical practice guidelines recommend screening for individuals at risk for osteoporotic fracture to identify individuals who may benefit from treatment [8].

Within the past 20 years, the gold standard test for diagnosing osteoporosis has been dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which measures bone mineral density (BMD). In the past few years, some experts have proposed a shift from use of BMD measures alone to estimation of absolute fracture risk over a period of time by incorporating clinical risk factors to identify individuals at high risk for osteoporotic fracture who may benefit from treatment. This new approach reflects understanding that clinical risk factors, in addition to BMD, have a significant independent impact on fracture risk, and are important to take into account when assessing osteoporotic fracture risk to identify individuals at high risk who may benefit from treatment. The use of clinical fracture risk assessment instruments has been endorsed in several national clinical practice guidelines [8], and is growing among clinicians.

There are multiple clinical fracture risk assessment instruments currently available, including the frequently used World Health Organization's Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) instrument. Many fracture risk assessment instruments have been validated in their development (derivation) populations for prediction of future fracture risk. However, it is important for clinicians, patients, and policymakers to know how well these instruments perform in populations other than their derivation cohort—specifically, how their predicted estimates of absolute fracture risk match observed fracture incidence in different populations in which they may be used—to be confident in their use.

The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature on osteoporosis clinical fracture risk assessment instruments to assess their performance in estimating absolute fracture risk over a given time period; specifically to compare predicted fracture probabilities to observed fracture probabilities (i.e., calibration) at different risk thresholds or categories in populations other than their derivation cohort.

Methods

Data sources and search strategies

We developed literature searches with the assistance of a professional research librarian (AAS) to identify studies that assessed the performance of osteoporosis clinical risk assessment instruments. Our search strategy was designed to identify studies of osteoporosis clinical fracture risk assessment instruments for predicting absolute fracture risk over a period of time, as well as studies of clinical risk assessment instruments for identifying individuals with osteoporosis by DXA criteria. In this study, we report findings for the systematic review of the performance of risk assessment instruments for predicting absolute fracture risk. The search terms used can be found in the complete MEDLINE search strategy which is shown in Supplementary material Table 1. Search strategies for the other databases are available from the authors upon request.

The following databases were searched: OvidSP MEDLINE (1948–June 2011), OvidSP MEDLINE Daily Update (June 2011), OvidSP In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (June 2011), Embase.com Embase (1974–2011), Wiley Cochrane Library (1898–2011), Scopus (1960–2011), ISI Web of Science limited to Proceeding Papers and Meeting Abstracts (1945–2011), ISI BIOSIS Previews limited to Meetings (1969–2011), ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (1861–2011), Health Services Research Projects in Progress (1995–2011), ClinicalTrials.gov (1999–2011), VHL LILACS (1982–2011), VHL IBECS (1999–2009), OpenGrey (1980–2005), and NRR Archives (2000–2007). All database literature searches were performed during June and July 2011.

In addition to database searching, the reference lists of relevant original studies and reviews were scanned to identify any additional relevant studies. Furthermore, individual issues of Osteoporosis International, the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, and Endocrine Reviews, from 1990 to 2011, were handsearched.

Study selection

We developed inclusion and exclusion criteria to select studies for this systematic review of the performance of clinical fracture risk assessment instruments for prediction of absolute fracture risk. We included studies done in adult populations that reported original data; assessed the performance of a clinical fracture risk assessment instrument to predict absolute future fracture risk; and provided predicted and observed fracture probabilities (or sufficient information to determine these probabilities) for different risk thresholds or categories of the instrument evaluated. We included studies of risk assessment instruments that contained a BMD component in addition to clinical risk factors, as long as the instrument had a clinical risk factor component. We included studies published in any language, in any type of adult patient population, in any type of publication (e.g., journal article, abstract, government report, dissertation) with no exclusions for any study participant characteristics.

We excluded studies done in patient populations that were composed of solely individuals with osteoporosis or osteopenia, and studies that did not provide both predicted and observed fracture probabilities (or sufficient data to determine these probabilities) for specific risk instrument thresholds or categories over a period of time. Thus, we excluded studies that only provided “average” predicted and observed probabilities of fracture over time for an entire study population rather than reporting separate performance data for several different risk thresholds or categories, as the “average” performance of an instrument is not sufficiently informative about the risk instrument's performance. For example, a risk assessment instrument could consistently overestimate probability of fracture for individuals of low risk and underestimate probability of fracture for individuals of high risk, and yet have an “average” predicted probability of fracture for the entire study population that is close to the observed probability of fracture; however, this would not be a well-performing instrument. We also excluded studies that presented findings only in units of rate per person-years rather than as a probability over a fixed period of follow-up time. We required that included studies of the performance of risk assessment instruments were done in populations other than the instrument derivation cohort, as the focus of this review was determining how these instruments perform in patients other than those whose data was used to develop the risk assessment instrument. Thus, we did not include studies in which the instruments were developed and validated in the same patients, or in which data from the study population was used in the development of the risk assessment instrument. We also excluded studies with a split-cohort design, in which the instrument was developed in one group of participants within a cohort and tested in a separate group of participants within that cohort.

Studies were assessed for potential inclusion in two stages, title/abstract and full-text. Studies that passed the title/abstract review were retrieved for full-text review. Foreign language studies were translated using the Google Translate translation system. All studies were assessed for inclusion/exclusion at the title/abstract stage by one reviewer (DLE); for any studies for which inclusion versus exclusion was unclear or there were questions about eligibility, a second reviewer (SN) assessed the studies to determine their eligibility for inclusion. All studies that were retrieved for full-text review were reviewed by two reviewers for inclusion (DLE and SN), and any disagreements about eligibility for inclusion were resolved by repeated review and discussion.

Data extraction

Data extracted from studies that met inclusion criteria included study location; year of publication; sociodemographics of participants; participant exclusion criteria; study funding source; study design details; number of study participants and dropouts/deaths; percentage of study participants who had osteoporosis, osteopenia, or history of osteoporotic fracture; risk assessment instrument evaluated and its components; types of fractures assessed; fracture follow-up time period; method of fracture ascertainment; risk assessment instrument thresholds or categories used to identify individuals at different levels of fracture risk; predicted fracture probability associated with each threshold/category; observed fracture probability over study time period for each threshold/category; and analysis details. Data were initially extracted by one author (DLE), and checked for accuracy by another author (SN). We contacted several authors for missing results data— for example, when a figure in an included article showed a graph of predicted and observed fracture probabilities, but exact numbers were not presented.

Data analysis

Due to wide heterogeneity in included study characteristics, including multiple different fracture risk assessment instruments and thresholds/categories evaluated, and diverse populations in which they were assessed, meta-analysis of study findings was not performed. Instead, we qualitatively described study findings, describing different study characteristics and findings regarding the performance of evaluated fracture risk assessment tools in various study populations; and examined potential sources of bias.

Results

Literature search and study selection

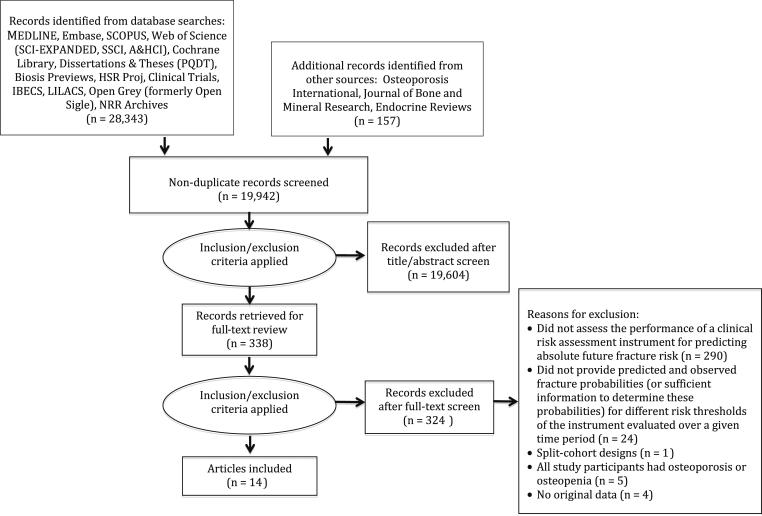

Our literature search identified 19,949 unique records for review. Of these studies, 14 met criteria for inclusion in this systematic review [9–22]. Figure 1 is a flow diagram that shows the number of records identified from databases and other sources; number of studies excluded at each stage of review and reasons for exclusion of full-text records reviewed (for example, 24 studies were excluded for not providing predicted and observed fracture probabilities for different risk thresholds/categories [23–46]); and number of studies that qualified for inclusion.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and study selection

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 details characteristics of the included studies. All included studies were peer-reviewed English-language journal articles published between 2005 and 2011, and all were cohort studies. Two Canadian cohorts were used in multiple studies—the Manitoba BMD cohort (four studies) [10, 14, 18, 20] and Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMOS) cohort (three studies) [10, 15, 17]; several studies assessed risk instrument performance in more than one cohort population. There was considerable heterogeneity among the study characteristics. Six studies assessed the WHO's FRAX instrument [10–12, 14, 16, 22]; two studies each evaluated the original Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada (CAROC) instrument [15, 18], the Garvan Institute fracture risk calculator [11, 15], or the 2001 Kanis risk algorithm (age and hip BMD T-score) [19, 20]; and the remainder of studies each assessed different risk instruments. Several studies assessed multiple risk instruments. Most studies assessed a risk instrument that included a BMD component. Five studies were done in Canada, five in Europe (three in the UK, one in Denmark, and one in Poland), two in the USA, one in Japan, and one in New Zealand. Nine studies included female participants only; and four of the other six studies had predominantly female participants, including three studies using the Manitoba BMD cohort. The average age of study participants ranged from 47 to 74, and sample sizes ranged from 501 to over two million participants. The majority of studies did not report the race/ethnicity of their participants; however, all but one of the studies were conducted in countries with predominantly white populations.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Study, year of publication | Country | Study participant description | Exclusion criteria | Number of participants | Age of participants in years | Sex of participants (% female/male) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bollandetal. 2011 [11] | New Zealand | Healthy New Zealand women age ≥55 years with normal lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) for their age (Z-score >-2) | No femoral neck BMD at baseline; no further data available after baseline visit; major medical condition/s; lumbar spine BMD Z-score <-2; taking treatment for osteoporosis (including hormone replacement therapy) or vitamin D supplements in doses >1,000 IU/day | 1,422 | Mean 74.2 (4.2) | Female (100 %) |

| Czerwinski et al. 2011 [22] | Poland | Convenience sample of 501 women from an urban region of Poland age 50 or older referred for assessment of BMD and clinical risk factors | Older than age 75 in 2009; incomplete documentation of FRAX risk factors; receiving treatment with bone active medication | 501 for FRAX without BMD; 269 for FRAX with BMD | 50–73; mean 61.0 (5.9) | Female (100 %) |

| Hippisley-Cox et al. 2009 [16] | England and Wales | Women and men aged 30-85 years from subset of practices in QResearch database—a large validated primary care database with data from nationally representative general practices in England and Wales | Previous recorded fracture (hip, distal radius, or vertebral); temporary residents; patients with interrupted periods of registration with the practice; individuals without a valid Townsend deprivation score related to the postcode | 878,835 | 40-85 years | Female (52 %); Male (48 %) |

| Leslie et al. 2011 [10] | Canada | Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos) cohort—community-dwelling randomly selected women and men living within 50 km of nine Canadian cities Manitoba Bone Density Program cohort —all women and men in the Province of Manitoba, Canada age 50 years or older at the time of a baseline femoral neck dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) |

Manitoba cohort -subjects who did not have medical coverage from Manitoba Health through 2008 | CaMos cohort - 6,697 Manitoba cohort— 39,603 |

≥50 (both cohorts) Means: CaMos—women 65.8 (8.8); men 65.3 (9.1) Manitoba—women 65.7 (9.8); men 68.2 (10.1) |

CaMos—Female (71 %); Male (29 %) Manitoba—Female (93 %); Male (7 %) |

| Leslie et al. 2010 [14] | Canada | Manitoba Bone Density Program cohort—all women and men in the Province of Manitoba, Canada age 50 years or older at the time of a baseline femoral neck DXA | Subjects who did not have medicalcoverage from Manitoba Health through March 2008 | 39,603 | ≥50: women—mean 65.7 (9.8); men—mean 68.2 (10.1) | Female (93 %); Male (7 %) |

| Tamakietal. 2011 [12] | Japan | Japanese Population-Based Osteoporosis (JPOS) Cohort—women randomly selected from Japanese municipalities | Age <40 years; age >75 years; no femoral neck BMD at baseline; taking osteoporosis drugs; taking hormone replacement therapy | 815 | 40–74; mean 56.7 (9.6) | Female (100 %) |

| Langsetmo et al. 2011 [15] | Canada | CaMos cohort (community-dwelling randomly selected women and men living within 50 km of nine Canadian cities) participants age 55–95 years at baseline who had undergone measurement of BMD and had at least 1 year of follow-up data | Individuals with missing data | 5,758 | 55–95: women—mean 67.70 (7.60); men—mean 67.60 (7.60) | Female (72 %); Male (28 %) |

| Leslie et al. 2010 [18] | Canada | Manitoba Bone Density Program cohort—all women and men in the Province of Manitoba, Canada age 50 years or older at the time of a baseline DXA | Individuals who did not have medical coverage from Manitoba Health during 4/1987 - 3/2008; individuals who did not have lumbar spine and proximal femur DXA results between 5/1998 and 3/2007 | 39,603 | ≥50: women—mean 65.7 (9.8); men—mean 68.2 (10.1) | Female (93 %); Male (7 %) |

| Abrahamsen et al. 2006 [19] | Denmark | Healthy, postmenopausal women 45-58 years of age in the non-hormone replacement therapy arms of The Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study (DOPS), either 3–24 months past last menstrual bleeding or still menstruating but having perimenopausal symptoms including menstrual irregularities with serum follicle-stimulating hormone >2 SD above the premenopausal mean | Diagnosed with metabolic bone disease, including osteoporosis defined as nontraumatic vertebral fractures on x-ray; current estrogen use or estrogen use within the past 3 months; current or past treatment with glucocorticoids > 6 months; current or past malignancy; newly diagnosed or uncontrolled chronic disease; alcohol or drug addiction; received raloxifene, bisphosphonates, or HRT | 872 | 45–58; mean 50.7 (2.9) | Female (100 %) |

| Leslie et al. 2008 [20] | Canada | Women over age 47.5 years from the Manitoba Bone Density Program who underwent baseline femoral neck BMD testing between January 1990 and October 2002 | Men and younger women (<47.5 years) | 20,579 | ≥47.5; mean 64 (10) | Female (100 %) |

| Collins etal. 2011 [21] | United Kingdom | Patients between ages 30 and 85 from 364 UK general practices contributing to The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database | Previous recorded fracture (hip, distal radius, or vertebra); not permanent residents of the United Kingdom; interrupted periods of registration with a practice; individuals without at least one yeafs complete data in their medical record | 2,244,636 for hip fracture endpoint; 2,209,451 for osteoporotic fractures endpoint | 30-85: women—median (IQRc) 48 (37–62); men—median (IQR ) 47 (37-59) | Female (50.6 %); Male (49.4 %) |

| Ettinger et al. 2005 [17] | USA | Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) and CaMos cohorts—community cohorts recruited from population listings of women | NRa | SOF—approximately 7,000b CaMos—approximately 5,000b |

SOF—65–79 CaMos—45–79 |

Female (100 %) |

| Loetal. 2011 [13] | USA | All female members of the Kaiser Permanente Northern California healthcare system aged 50 to 85 years with hip BMD measured during 1997–2003 | Individuals without 1 year of continuous membership both prior to and after DXA; DXA not electronically accessible; missing race/ethnicity; filled bisphosphonate prescription in the year prior to DXA | 94,489 | 50–85; mean 62.8 (8.6) | Female (100 %) |

| van Staa et al. 2006 [9] | UK | Random sample of women aged 50 years and older from the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) | Recent use of oral glucocorticoids; patients from general practices that contribute medical records to both The Health Improvement Network (THIN) and GPRD databases | 32,728 | ≥50 | Female (100 %) |

| Study, year of publication | Race/ethnicity of participants | Participants who had osteoporosis, osteopenia, or prior fracture history at baseline (%) | Risk instruments) evaluated | Types of fractures ascertained | Length of follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bollandetal. 2011 [11] | NRa | Osteoporosis (femoral neck)—11 % Osteopenia (femoral neck)—55 % Prior fracture during adult life (not specified whether osteoporotic) -33.5 % |

1.FRAX—New Zealand, with and without BMDd 2.Garvan Institute fracture risk calculatore |

FRAX: Osteoporotic fractures (shoulder, hip, forearm, and clinical vertebral) Garvan: Osteoporotic fractures (hip, vertebrae (symptomatic), forearm, metacarpal, humerus, scapula, clavicle, distal femur, proximal tibia, patella, pelvis, and sternum) |

Mean 8.8 years (range 0.2–11.4 years) |

| Czerwinski et al. 2011 [22] | NRa | Prior fracture (not specified whether osteoporotic) -30 % Secondary osteoporosis -13 % |

FRAX—United Kingdom (UK) version 3.0 with and without BMDf | Major osteoporotic fractures (hip, clinical vertebral, forearm, and humerus) | 9–12 years |

| Hippisley-Cox et al. 2009 [16] | NRa | NRa | FRAX algorithm—UK version without BMDg | Hip fractures | 10 years |

| Leslie etal. 2011 [10] | NRa | Prior osteoporotic fracture: CaMos: women - 11.3 %; men - 4.9 %; Manitoba: women—13.6 %; men—15.0 % |

1.FRAX—model for Canada with BMDh 2.The updated Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada (CAROC) systemi |

Major osteoporotic fractures (hip, forearm, humerus, and clinical spine) | 10 years |

| Leslie etal. 2010 [14] | NRa | Osteoporosis: women—30.9 %; men—19.3 % Prior osteoporotic fracture: women—13.6 %; men—15 % |

FRAX—model for Canada, with and without femoral neck BMDj | Osteoporotic fractures (hip, clinical vertebral, forearm, and humerus) | 10 years |

| Tamakietal. 2011 [12] | Japanese | Prior osteoporotic fracture: 8 % at hip, vertebrae, distal forearm, or proximal humerus; 11 % at any skeletal sites | FRAX—Japanese version 3.0 with and without BMDk | 1.Major osteoporotic fractures (hip, clinical vertebral, forearm, proximal humerus) 2.Hip fractures |

10 years |

| Langsetmo et al. 2011 [15] | NRa | Prior fracture after age 50: women—12.6 %; men—5.5 % | 1.Dubbo Nomogram (Garvan Institute fracture risk calculator)l 2. The Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada (CAROC) system (original CAROC)m |

1. Low-trauma fractures (fractures of the skull, face, hands, ankles, and feet were excluded) 2. Hip fractures |

Women—mean 8.6 years; Men—mean 8.3 years |

| Leslie etal. 2010 [18] | NRa | Osteoporosis: women—30.9 %; men—19.3 % (using female reference data) vs. 27.9 % (using sex-matched reference data) Prior osteoporotic fracture: women—13.6 %; men—15.0 % |

The Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada (CAROC) system (original CAROC)m | Major osteoporotic fractures (hip, clinical vertebral, forearm, and humerus) | Women—mean 5.4 years (range 0–10 years) Men—mean 4.4 years (range 0–10 years) |

| Abrahamsen et al. 2006 [19] | NRa | Prior fragility fracture (>45 years)—0.6 % | 2001 Kanis risk algorithmicn | Major osteoporotic fractures (hip, clinical vertebral, shoulder, and wrist) | 10 years |

| Leslie et al. 2008 [20] | White (98.1 %) | Osteoporosis (femoral neck)—16.1 % | 1. Ten-year fracture risk according to age-only and age plus BMDo 2. 2001 Kanis risk algorithmp |

Osteoporotic fractures (hip, clinical vertebral, forearm, and proximal humerus) | Mean 4.2 years, maximum 10 years |

| Collins et al. 2011 [21] | NRa | NRa | QFractureScoresq | 1. Osteoporotic fractures (hip, distal radius, and vertebra) 2. Hip fractures |

Osteoporotic fractures—median (IQRc) 5.98 years (2.61–8.50) Hip fractures—median (IQR ) 6.03 years (2.62–8.50) Maximum follow-up 10 years (14.5 % for osteoporotic fractures endpoint; 14.7 % for hip fractures end point |

| Ettinger et al. 2005 [17] | Primarily non-Hispanic white women | NRa | Excel spreadsheet-based model of fracture riskr | 1. Three major osteoporotic non-spinal fractures (hip, humerus, and wrist) 2. Clinical spinal fractures |

5 years |

| Loetal. 2011 [13] | White—76.1 % Asian—13.9 % Hispanic—6.0 % Black—4.0 % |

Osteoporosis (femoral neck)—11.2 % Osteopenia (femoral neck)—49.7 % Prior osteoporotic fracture—10.1 % |

Fracture Risk Calculator (FRC)s | Hip fractures | Median (IQRc) 6.6 years (3.6–8.3) |

| van Staa et al. 2006 [9] | NRa | NRa | A risk score predicting the 5-year risk of fracturet | 1. Femur/hip 2. Clinical vertebral 3. Other clinical osteoporotic fractures (i.e., radius/ulna, humerus, rib, pelvis) |

Mean 5.6 years |

Not reported

Information provided by author

Interquartile range

FRAX—New Zealand version, with and without BMD components: age, gender, BMI, history of personal fracture, history of parental hip fracture, smoking status, glucocorticoid use, alcohol intake, rheumatoid arthritis, secondary osteoporosis, with or without BMD T-score (femoral neck)

Garvan Institute fracture risk calculator components: age, gender, BMD T-score (femoral neck), number of falls in the past year, number of fractures since age 50 years

FRAX—UK version 3.0 with and without bone mineral density (BMD) components: age, sex, weight, height, previous fracture, parental history of hip fracture, current smoker, glucocorticoid use, secondary osteoporosis (history of hyperparathyroidism, diabetes, asthma, or early menopause), with or without BMD T-score (femoral neck)

FRAX without BMD components: age, sex, height, weight, previous fracture, parental history of hip fracture, current smoking, glucocorticoid treatment, rheumatoid arthritis, secondary osteoporosis, use of alcohol (>3 units/day)

FRAX—Canada version with BMD components: age, sex, weight, height, BMD T-score (femoral neck), prior fragility fracture, parental hip fracture, rheumatoid arthritis, secondary osteoporosis, prior glucocorticoid use, current smoking, alcohol use ≥3 units

The updated CAROC system components: age, sex, BMD T-score (femoral neck), prior fragility fracture, glucocorticoid use

FRAX—Canada version, with and without femoral neck BMDcomponents: age, sex, weight, height, prior osteoporotic fracture, rheumatoid arthritis, corticosteroid use, current smoking, alcohol >3 units/day, parental hip fracture, with or without BMD T-score (femoral neck)

FRAX—Japanese version 3.0 with and without BMD components: age, sex, weight, height, current smoker, alcohol 3 or more units daily, secondary osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, glucocorticoid use, previous fragility fracture, parental history of hip fracture, with or without BMD T-score (femoral neck)

Dubbo Nomogram (Garvan Institute fracture risk calculator) components: age, sex, BMD T-score (femoral neck), fracture history after age 50 (low-trauma), falls in the last year

The original CAROC system components: age, minimum BMD T-score (femoral neck, lumbar spine, total hip, trochanter), fracture after age 40, glucocorticoid use

2001 Kanis risk algorithm components: age, BMD T-score (hip)

Ten-year fracture risk algorithm components: age-only and age plus BMD T-score (femoral neck)

2001 Kanis risk algorithm components: age, BMD T-score (femoral neck)

QfractureScores components: men and women—age, BMI, smoking status, recorded alcohol use, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, asthma, at least two prescriptions for tricyclic antidepressants in 6 months prior, at least two prescriptions for corticosteroids in 6 months prior, history of falls, diagnosis of chronic liver disease; women only—parental history of osteoporosis, diagnosis of gastrointestinal malabsorption, diagnosis of other endocrine symptoms, at least two prescriptions of hormone replacement therapy, menopausal symptoms

Excel spreadsheet-based model of fracture risk components: age, height, weight, current smoker, prior non-spine fracture, number of spinal fractures, sister had hip fracture, other had hip fracture, BMDZscore (hip and spine)

Fracture Risk Calculator (FRC) components: age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, femoral neck BMD Z-score, current smoking, alcohol >3 units/day, glucocorticoid exposure, fracture after age 45 years, parent with hip fracture, rheumatoid arthritis, secondary cause of bone loss

A risk score predicting the 5-year risk of fracture components: age, fracture history, fall history, body mass index, smoker, chronic disease (with or without recent general practitioner visit/hospitalization), recent use of central nervous system medication, history of early menopause

Six studies reported the prevalence of osteoporosis by DXA criteria in their study population, with prevalences ranging from 11 to 30.9 %. Ten studies reported prior fracture history of participants, with prevalences ranging from 0.6 to 33.5 %; however, two studies that reported prior fracture prevalences of greater than 30 % did not specify whether they were fragility fractures [11, 22]. Five studies excluded participants who were receiving or had received medical therapy for osteoporosis or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) [11–13, 19, 22], and two studies excluded individuals who had a history of osteoporotic fracture [16, 21]. The majority of studies did not report details about the medical comorbidities or medication use of their study participants; however, several studies reported that their participants were relatively healthy. Most studies reported 10-year fracture outcomes. The majority of studies reported combined probabilities of multiples types of osteoporotic fractures (ex. hip, vertebral, forearm); two studies reported hip fracture probabilities only [13, 16]. Approximately equal numbers of studies ascertained fracture occurrence by medical records review versus study participant self-report.

Performance of clinical risk assessment tools for predicting absolute future fracture risk (calibration)

Table 2 shows individual study findings for predicted and observed probabilities of fracture for different risk thresholds/categories. A slight majority of studies reported good calibration of at least one risk assessment instrument evaluated [9–12, 14, 15, 20, 21], with observed fracture probabilities being close to predicted probabilities at different risk thresholds/categories evaluated; however, two of these studies involved evaluation of the same risk assessment instrument (FRAX) in the same study cohort [10, 14]. Conversely, seven studies reported suboptimal calibration of at least one evaluated risk instrument [11, 13, 16–19, 22].

Table 2.

Study findings and potential sources of bias

| Study first author, year of publication | Risk instrument(s) evaluated | Fracture risk prediction period (years) | Predicted an d observed fracture probabilities for each risk category evaluated |

Method of fracture ascertainment | Percentage of eligible cohort who were lost to follow-up or died during study period | Missing or substituted data for at least one instrument risk factor? (yes/no) | Pharmaceutical industry funding or author disclosure? (yes/no) | Authorship by risk instrument developer? (yes/no) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolland et al. 2011 [11] | 1. The FRAX—New Zealand tool with and without BMD | 10 | Risk categories—deciles of estimated fracture probability | Self-report | 21 % (17 %died, 4 % lost to follow-up) | No | No | No | |||

| 2. Garvan Institute fracture risk calculator | FRAX with BMD—osteoporotic fracturese: | ||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted | Observed (95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.02 | 0.08 (0.03–0.12) | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.04 | 0.09 (0.04–0.14) | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.05 | 0.08 (0.04–0.13) | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.06 | 0.13 (0.07–0.18) | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.07 | 0.15 (0.09–0.21) | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.08 | 0.19 (0.13–0.25) | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.09 | 0.17 (0.11–0.24) | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.1 | 0.17 (0.11–0.23) | |||||||||

| 9 | 0.14 | 0.23 (0.16–0.3) | |||||||||

| 10 | 0.22 | 0.32 (0.24–0.39) | |||||||||

| FRAX without BMD—osteoporotic fracturese: | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted | Observed (95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.03 | 0.07 (0.03–0.11) | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.06 | 0.14 (0.08–0.2) | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.07 | 0.07 (0.03–0.11) | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.08 | 0.12 (0.07–0.17) | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.09 | 0.17 (0.11–0.23) | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.11 | 0.2 (0.13–.26) | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.13 | 0.17 (0.11–0.23) | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.15 | 0.17 (0.11–0.23) | |||||||||

| 9 | 0.18 | 0.2 (0.13–0.26) | |||||||||

| 10 | 0.27 | 0.31 (0.23–0.39) | |||||||||

| FRAX with BMD—hip fracturese: | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted | Observed (95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.002 | 0.007 (0–0.021) | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.005 | 0.014 (0–0.034) | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.008 | 0.014 (0–0.034) | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.012 | 0.042 (0.009–0.075) | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.016 | 0.014 (0–0.034) | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.02 | 0.035 (0.005–0.066) | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.027 | 0.035 (0.005–0.065) | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.036 | 0.035 (0.005–0.066) | |||||||||

| 9 | 0.054 | 0.12 (0.066–0.173) | |||||||||

| 10 | 0.124 | 0.085 (0.039–0.13) | |||||||||

| FRAX without BMD—hip fracturese | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted | Observed (95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.01 | 0 (0–0) | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.018 | 0.014 (0–0.034) | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.024 | 0.021 (0–0.045) | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.029 | 0.035 (0.005–0.065) | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.037 | 0.028 (0.001–0.055) | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.045 | 0.042 (0.009–0.075) | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.055 | 0.063 (0.023–0.103) | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.069 | 0.035 (0.005–0.066) | |||||||||

| 9 | 0.091 | 0.063 (0.023–0.104) | |||||||||

| 10 | 0.171 | 0.099 (0.05–0.148) | |||||||||

| Garvan—osteoporotic fracturese: | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted | Observed (95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.05 | 0.08 (0.03–0.12) | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.08 | 0.13 (0.07–0.18) | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.11 | 0.13 (0.08–0.19) | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.13 | 0.18 (0.12–0.25) | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.15 | 0.15 (0.1–0.21) | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.18 | 0.16 (0.1–0.22) | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.2 | 0.24 (0.17–0.31) | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.24 | 0.27 (0.19–0.34) | |||||||||

| 9 | 0.3 | 0.31 (0.23–0.39) | |||||||||

| 10 | 0.49 | 0.31 (0.23–0.39) | |||||||||

| Garvan—hip fracturese | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted | Observed (95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.004 | 0.007 (0–0.021) | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.01 | 0.028 (0.001–0.055) | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.015 | 0.021 (0–0.045) | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.022 | 0.021 (0–0.045) | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.029 | 0.021 (0–0.045) | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.038 | 0.035 (0.005–0.066) | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.049 | 0.049 (0.014–0.084) | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.066 | 0.07 (0.028–0.113) | |||||||||

| 9 | 0.103 | 0.056 (0.018–0.094) | |||||||||

| 10 | 0.267 | 0.092(0.044–0.139) | |||||||||

| Czerwinski et al. 2011 [22] | FRAX—UK (version 3.0) with and without BMD | 10 | Risk categories—fracture risk by FRAX score percentiles (10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th) | Self–report | 59 % of potentially eligible study cohort could not be recontacted | No | No | Yes | |||

| FRAX without BMD—major osteoporotic fractures: | |||||||||||

| Percentile | Predicted (%) | ||||||||||

| 10 | 4.13 | ||||||||||

| 25 | 5.35 | ||||||||||

| 50 | 8.40 | ||||||||||

| 75 | 13.81 | ||||||||||

| 90 | 17.28 | ||||||||||

| Observed/predicted ratio (95 % CI)—1.79 (1.44–2.21) | |||||||||||

| FRAX with BMD—major osteoporotic fractures: | |||||||||||

| Percentile | Predicted (%) | ||||||||||

| 10 | 3.81 | ||||||||||

| 25 | 5.33 | ||||||||||

| 50 | 8.29 | ||||||||||

| 75 | 13.25 | ||||||||||

| 90 | 18.89 | ||||||||||

| Observed/predicted ratio (95 % CI)—1.94 (1.45–2.54) | |||||||||||

| Hippisley-Cox et al. 2009 [16] | FRAX algorithm—UK version without BMD | 10 | FRAX score risk categories—score deciles | Medical records review | NRa | Yes | No | No | |||

| FRAX without BMD—hip fractures (women): | |||||||||||

| Decile | Mean Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.16 | 0.08 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.16 | 0.08 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.30 | 0.17 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.40 | 0.25 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.54 | 0.33 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.83 | 0.61 | |||||||||

| 7 | 1.37 | 1.06 | |||||||||

| 8 | 2.46 | 1.99 | |||||||||

| 9 | 4.74 | 4.34 | |||||||||

| 10 | 10.07 | 9.33 | |||||||||

| FRAX without BMD—hip fractures (men): | |||||||||||

| Decile | Mean Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.10 | 0.06 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.10 | 0.06 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.20 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.20 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.30 | 0.17 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.40 | 0.24 | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.59 | 0.34 | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.98 | 0.52 | |||||||||

| 9 | 1.76 | 1.36 | |||||||||

| 10 | 3.87 | 3.31 | |||||||||

| Leslie et al. 2011 [10] | 1. Canadian FRAX with BMD | 10 | Risk categories—low (10 %), moderate (10–20 %), and high (>20 %) predicted probability | CaMos—self-report | NRa | Manitoba cohort—yes; | Yes | Yes | |||

| 2. The updated Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada (CAROCc) system | FRAX with BMD—major osteoporotic fractures (Manitoba cohort): | Manitoba—medical records review | CaMos cohort—no | ||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <10 | 6.6 | ||||||||||

| 10–20 | 16.1 | ||||||||||

| >20 | 31.0 | ||||||||||

| Updated CAROCc - major osteoporotic fractures (CaMosb cohort): | |||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <10 | 6.1 | ||||||||||

| 10–20 | 13.5 | ||||||||||

| >20 | 22.3 | ||||||||||

| Leslie et al. 2010 [14] | FRAX—(model for Canada) with and without femoral neck BMD | 10 | First analysis risk categories—quintiles of FRAX-estimated probability | Database/medical records review | NRa | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| FRAX with BMD—osteoporotic fractures (women)c: | |||||||||||

| Quintile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%, 95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 4.39 | 4.61±1.01 | |||||||||

| 2 | 6.53 | 6.55±0.99 | |||||||||

| 3 | 8.92 | 9.02±1.26 | |||||||||

| 4 | 12.77 | 14.99±1.67 | |||||||||

| 5 | 23.03 | 26.51±2.07 | |||||||||

| FRAX with BMD—osteoporotic fractures (men)e: | |||||||||||

| Quintile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%, 95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 3.83 | 4.30±2.56 | |||||||||

| 2 | 5.49 | 4.25±3.03 | |||||||||

| 3 | 7.19 | 13.22±5.05 | |||||||||

| 4 | 9.43 | 11.39±4.57 | |||||||||

| 5 | 15.96 | 18.95±5.47 | |||||||||

| FRAX with BMD—hip fractures (women)e: | |||||||||||

| Quintile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%, 95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.13 | 0.12±0.12 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.46 | 0.47±0.24 | |||||||||

| 3 | 1.15 | 1.18±0.49 | |||||||||

| 4 | 2.86 | 2.96±0.70 | |||||||||

| 5 | 9.55 | 9.82±1.53 | |||||||||

| FRAX with BMD—hip fractures (men)e: | |||||||||||

| Quintile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%, 95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.24 | 0.73±1.43 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.80 | 0.34±0.67 | |||||||||

| 3 | 1.76 | 4.77±3.70 | |||||||||

| 4 | 3.33 | 3.43±2.92 | |||||||||

| 5 | 8.51 | 7.09±3.10 | |||||||||

| Second analysis risk categories—low (<10 %), moderate (10–20 %), high (>20 %) predicted risk | |||||||||||

| FRAX without BMD—osteoporotic fractures (women and men combined)e: | |||||||||||

| Risk category (%) | Predicted (%) Observed (%, 95 % CI) | ||||||||||

| <10 | 6.84 | 6.66±0.62 | |||||||||

| 10-20 | 14.78 | 16.37±1.35 | |||||||||

| >20 | 26.10 | 31.01±2.82 | |||||||||

| Tamaki et al. 2011 [12] | FRAX—Japanese version 3.0 with and without BMD | 10 | Risk categories—quartiles of FRAX-estimated probability | Self-report | NRa | Yes | No | No | |||

| FRAX with FN BMD—major osteoporotic fractures: | |||||||||||

| Quartile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.4 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| 2 | 3.7 | 4.5e | |||||||||

| 3 | 6.1 | 5.8e | |||||||||

| 4 | 11.0 | 9.9 | |||||||||

| FRAX without FN BMD—major osteoporotic fractures: | |||||||||||

| Quartile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| 2 | 3.7 | 5.4e | |||||||||

| 3 | 5.6 | 5.9e | |||||||||

| 4 | 12.0 | 8.9 | |||||||||

| FRAX with BMD—hip fractures: | |||||||||||

| Quartile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.6 | 0.5e | |||||||||

| 4 | 2.2 | 1.5 | |||||||||

| FRAX without BMD—hip fracturese: | |||||||||||

| Quartile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.6 | 0.56 | |||||||||

| 4 | 2.7 | 1.4 | |||||||||

| Langsetmo et al. 2011 [15] | 1. Dubbo Nomogram (Garvan Institute fracture risk calculator) | 10 | Risk categories—quintiles according to risk predicted by the nomogram Hip fractures (women)e: | Self-report; 78 % of fractures with documented confirmation | NRa | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Quintile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%, 95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.6 | 0.4 (0.1–1.3) | |||||||||

| 2 | 1.4 | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | |||||||||

| 3 | 2.4 | 1.6 (0.9–3.0) | |||||||||

| 2. The original Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada (CAROCc) system | 4 | 4.5 | 3.0 (2.0–4.7) | ||||||||

| 5 | 19.2 | 9.7 (7.5–12.5) | |||||||||

| Hip fractures (men)e: | |||||||||||

| Quintile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%, 95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.1 | 0.4 (0.1–2.7) | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.9 | 0.7 (0.2–2.8) | |||||||||

| 4 | 2.0 | 2.6 (1.2–5.8) | |||||||||

| 5 | 10.0 | 10.2 (6.6–15.5) | |||||||||

| Any low-trauma fractures (women)6: | |||||||||||

| Quintile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%, 95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 7.0 | 5.4 (3.9–7.3) | |||||||||

| 2 | 10.7 | 10.3 (8.4–12.8) | |||||||||

| 3 | 14.2 | 14.1 (11.7–16.8) | |||||||||

| 4 | 19.3 | 20.6 (17.7–24.0) | |||||||||

| 5 | 40.5 | 33.4 (29.8–37.3) | |||||||||

| Any low-trauma fractures (men)e: | |||||||||||

| Quintile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%, 95 %CI) | |||||||||

| 1 | 2.9 | 2.7 (1.3–5.3) | |||||||||

| 2 | 4.8 | 3.8 (2.1–6.7) | |||||||||

| 3 | 7.6 | 6.3 (4.0–9.9) | |||||||||

| 4 | 12.6 | 10.0 (6.8–14.5) | |||||||||

| 5 | 30.9 | 25.0 (19.3–32.1) | |||||||||

| Risk categories—low (0–10 %), moderate (10–20 %), and high (>20 %) predicted probability | |||||||||||

| Original CAROCc—major osteoporotic fractures (CaMosb cohort) (women): | |||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <10 | 6.2 | ||||||||||

| 10–20 | 13.8 | ||||||||||

| >20 | 29.7 | ||||||||||

| Original CAROCc—major osteoporotic fractures (CaMosb cohort) (men): | |||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <10 | 5.6 | ||||||||||

| 10–20 | 23.3 | ||||||||||

| >20 | 35.1 | ||||||||||

| Leslie etal. 2010 [18] | The Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada (CAROCc) system (original CAROC) | 10 | Risk categories—low (<10 %), moderate (10–20 %), high (>20 %) predicted probability | Medical records review | NRa | No | Yes | Yes | |||

| Osteoporotic fractures—femoral neck risk category (women): | |||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <10 | 5.6 | ||||||||||

| 10–20 | 10.0 | ||||||||||

| >20 | 23.3 | ||||||||||

| Osteoporotic fractures—femoral neck risk category (men): | |||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <10 | 7.2 | ||||||||||

| 10–20 | 10.7 | ||||||||||

| >20 | 22.3 | ||||||||||

| Osteoporotic fractures—minimum site risk category (women): | |||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <10 | 5.1 | ||||||||||

| 10–20 | 8.2 | ||||||||||

| >20 | 20.8 | ||||||||||

| Osteoporotic fractures—minimum site risk category (men): | |||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <10 | 6.6 | ||||||||||

| 10–20 | 10.7 | ||||||||||

| >20 | 19.5 | ||||||||||

| Abrahamsen et al. 2006 [19] | 2001 Kanis risk algorithm | 10 | Risk categories—fracture risk by BMD T-score at menopause | Verified reports | 16 % left the study or declined to attend 10-year visit | No | No | No | |||

| Osteoporotic fractures: | |||||||||||

| Total hip T-score | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| +1 | 2.4 | 6.3 | |||||||||

| +0.5 | 3.0 | 7.2 | |||||||||

| 0 | 3.8 | 8.2 | |||||||||

| −0.5 | 4.7 | 9.4 | |||||||||

| −1 | 5.9 | 10.7 | |||||||||

| −1.5 | 7.4 | 12.0 | |||||||||

| −2 | 9.2 | 13.6 | |||||||||

| −2.5 | 11.3 | 15.4 | |||||||||

| Leslie et al. 2008 [20] | 1. Ten-year fracture risk according to age-only | 10 | Risk categories (first analysis) - fracture risk by age strata | Medical records review | 5.7 % died; 2.2 % lost to relocation | No | No | No | |||

| Osteoporotic fractures: | |||||||||||

| 2. 2001 Kanis risk algorithm - ten-year fracture risk according to age plus femoral neck T-score | Age | Predicted (%) | Observed-direct (%, SE) | Observed-actuarial (%, SE) | |||||||

| 50 | 6.0 | 6.7 (1.1) | 6.5 (0.5) | ||||||||

| 55 | 7.8 | 6.9 (1.1) | 8.8 (0.6) | ||||||||

| 60 | 10.6 | 10.7 (1.5) | 10.8 (0.7) | ||||||||

| 65 | 14.3 | 10.9 (1.4) | 13.2 (0.9) | ||||||||

| 70 | 18.9 | 15.6 (2.0) | 18.5 (1.1) | ||||||||

| 75 | 22.9 | 25.9 (3.7) | 24.8 (1.8) | ||||||||

| 80 | 26.5 | 41.8 (6.6) | 36.2 (3.9) | ||||||||

| 85 | 27.0 | 45.5 (9.5) | 41.7 (7.4) | ||||||||

| Risk categories (second analysis)—fracture risk by estimated risk strata according to age plus femoral neck T-score | |||||||||||

| Osteoporotic fractures: | |||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed-direct (%, SE) | Observed-actuarial (%, SE) | |||||||||

| 0-4 | 3.2 (1.4) | 3.7 (0.5) | |||||||||

| 5-9 | 7.7 (1.0) | 7.5 (0.5) | |||||||||

| 10-14 | 9.2 (1.0) | 12.1 (0.7) | |||||||||

| 15-19 | 16.1 (1.8) | 16.8 (1.0) | |||||||||

| 20-24 | 22.5 (2.7) | 22.7 (1.6) | |||||||||

| 25-29 | 30.8 (4.1) | 33.3 (2.5) | |||||||||

| >30 | 45.8 (5.1) | 45.4 (3.1) | |||||||||

| Collins et al. 2011 [21] | QFractureScores | 10 | Risk categories—deciles of predicted risk | Medical records review | NRa | Yes | No | No | |||

| Osteoporotic fractures (women)e: | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.41 | 0.34 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.53 | 0.38 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.64 | 0.46 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.81 | 0.58 | |||||||||

| 5 | 1.11 | 0.86 | |||||||||

| 6 | 1.60 | 1.34 | |||||||||

| 7 | 2.40 | 2.18 | |||||||||

| 8 | 3.85 | 3.45 | |||||||||

| 9 | 6.66 | 6.58 | |||||||||

| 10 | 13.71 | 14.43 | |||||||||

| Osteoporotic fractures (men)e: | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.40 | 0.30 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.46 | 0.37 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.51 | 0.38 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.56 | 0.44 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.62 | 0.54 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.69 | 0.59 | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.81 | 0.69 | |||||||||

| 8 | 1.04 | 0.87 | |||||||||

| 9 | 1.64 | 1.73 | |||||||||

| 10 | 4.59 | 4.77 | |||||||||

| Hip fractures (women)e: | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.06 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.11 | 0.14 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.20 | 0.26 | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.39 | 0.51 | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.94 | 1.22 | |||||||||

| 9 | 2.64 | 3.14 | |||||||||

| 10 | 9.12 | 10.19 | |||||||||

| Hip fractures (men)e: | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.02 | 0.05 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.06 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.08 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.12 | 0.17 | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.18 | 0.21 | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.33 | 0.38 | |||||||||

| 9 | 0.74 | 0.92 | |||||||||

| 10 | 3.63 | 3.47 | |||||||||

| Ettinger et al. 2005 [17] | Excel spreadsheet-based model of fracture risk | 5 | Risk categories—one of six levels of predicted fracture risk from model: <2.5, 2.5–4.9, 5–7.4, 7.5–9.9, and 10+% | CaMos—self-report | NRa | No | Yes | Yes | |||

| Any one of three nonspinal fractures (SOFd cohort): | SOFdself-report, with physician adjudication of fracture reports and medical records | ||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <2.5 | 0.8 | ||||||||||

| 2.5–4.9 | 2.1 | ||||||||||

| 5–7.4 | 4.0 | ||||||||||

| 7.5–9.9 | 5.7 | ||||||||||

| 10+ | 9.3 | ||||||||||

| Any one of three nonspinal fractures (CaMosb cohort): | |||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <2.5 | 0.5 | ||||||||||

| 2.5–4.9 | 1.9 | ||||||||||

| 5–7.4 | 1.9 | ||||||||||

| 7.5–9.9 | 3.9 | ||||||||||

| 10+ | 5.4 | ||||||||||

| Clinical spinal fractures (CaMosb cohort): | |||||||||||

| Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | ||||||||||

| <2.5 | 0.7 | ||||||||||

| 2.4–4.9 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| 5–7.4 | 1.4 | ||||||||||

| 7.5–9.9 | 2.4 | ||||||||||

| Lo et al. 2011 [13] | Fracture Risk Calculator (FRC) | 10 | Risk categories—<1, 1–2.9, or 3–4.9 % predicted probability | Medical records review | NRa | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Hip fractures: Predicted probability category (%) | Median predicted probability (%) | Observed probability (%) |

|||||||||

| <1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |||||||||

| 1–2.9 | 1.6 | 2.0 | |||||||||

| 3–4.9 | 3.7 | 5.0 | |||||||||

| van Staa et al. 2006 [9] | A risk score predicting the 5-year risk of fracture | 5 | Risk categories—deciles based on the fracture risk score in each dataset | Confirmed by general practitioner (91 % cases); vertebral fractures confirmed radiographically | NRa | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Femur/hip fractures: | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | |||||||||

| 4 | 1.2 | 0.6 | |||||||||

| 5 | 1.9 | 2.3 | |||||||||

| 6 | 3.4 | 4.0 | |||||||||

| 7 | 4.8 | 4.8 | |||||||||

| 8 | 5.9 | 6.8 | |||||||||

| 9 | 7.4 | 7.4 | |||||||||

| 10 | 12.1 | 11.4 | |||||||||

| Clinical vertebral fractures: | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.4 | 0.6 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.6 | 0.5 | |||||||||

| 9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| 10 | 1.2 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| Other clinical osteoporotic fractures: | |||||||||||

| Decile | Predicted (%) | Observed (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 2.8 | 3.6 | |||||||||

| 2 | 3.2 | 2.1 | |||||||||

| 3 | 3.6 | 3.1 | |||||||||

| 4 | 4.0 | 5.3 | |||||||||

| 5 | 4.4 | 3.2 | |||||||||

| 6 | 4.8 | 5.4 | |||||||||

| 7 | 5.0 | 6.4 | |||||||||

| 8 | 5.5 | 5.3 | |||||||||

| 9 | 6.4 | 6.6 | |||||||||

| 10 | 8.3 | 6.8 | |||||||||

Not reported

Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study

The Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada

Study of Osteoporotic Fractures

Data obtained from author correspondence

The six studies that assessed the calibration of the FRAX risk assessment instrument reported mixed performance. Two of these studies assessed different forms of FRAX in one Canadian cohort, the Manitoba BMD cohort, and these studies found good calibration of FRAX in that cohort [10, 14]. The other four studies that assessed FRAX were performed in different countries (the UK, New Zealand, Japan, and France) [11, 12, 16, 22], and three of these studies reported suboptimal FRAX calibration [11, 16, 22]. Thus, suboptimal calibration of FRAX was found in three of the five separate cohorts in which this tool was evaluated. Three studies assessed the calibration of FRAX with a BMD component as well as without a BMD component, and found comparable performance of the FRAX model with and without a BMD component [11, 12, 22].

Two studies assessed the Garvan Institute fracture risk calculator—one study by Langsetmo and colleagues found the calibration to be generally good, except for overprediction of risk in the highest risk quintiles [15]; another study by Bolland and colleagues found the instrument to be well calibrated for Garvan-defined osteoporotic fractures but overestimate hip fractures [11]. Two studies assessed the original CAROC system and found poor calibration [15, 18]. Two studies assessed the 2001 Kanis risk algorithm that includes age and BMD, with mixed calibration performance findings [19, 20]. One study assessed the QFracturesScores risk instrument, and found good instrument calibration in a large nationally representative cohort in the UK [21]. The remainder of risk assessment instruments in included studies were also assessed in only one study; the findings with respect to the calibration of these other risk assessment instruments assessed were mixed, with some instruments found to have good calibration in the study populations in which they were assessed (e.g., the updated CAROC system) [9, 10, 20], and others found to have poor calibration in the population in which they were assessed [13, 17].

A similar proportion of the relatively simple risk assessment instruments (≤5 clinical variables; including the Garvan Institute fracture risk calculator, 2001 Kanis risk algorithm, and 10-year fracture risk according to age only) evaluated in included studies were found to have good calibration when compared with studies that assessed complex risk assessment instruments (>5 clinical variables; including FRAX, QFractureScores, CAROC system, Fracture Risk Calculator (FRC), an Excel spreadsheet-based model of fracture risk [17], and a risk score predicting the 5-year risk of fracture [9]), with a slight majority of both simple and complex instruments found to have good calibration. There were also no clear differences noted in the proportion of risk assessment instruments with a BMD component versus those without a BMD component found to have good versus poor calibration. Additionally, no clear differences were apparent in the calibration performance of risk assessment instruments evaluated in female versus male study participants, although data for men were limited to only a few studies.

Two out of five studies that exclude participants who had received medical therapy for osteoporosis or hormone therapy reported good calibration of an evaluated risk assessment instrument for fracture prediction, whereas six of the nine studies that did not exclude participants who had received osteoporosis treatment or hormone replacement therapy reported good risk instrument calibration.

Study quality/potential sources of bias

We compared studies on several quality measures to identify potential sources of bias in study findings (Table 2). No clear relationship was apparent between study size (number of study participants) and reported instrument calibration performance. Most studies did not indicate the percentage of the eligible study cohort who were lost to follow-up or died during the fracture risk prediction period. Six included studies were supported by pharmaceutical industry funding or had an author who received support from a pharmaceutical company [9, 10, 14, 15, 17, 18]; no clear relationship was apparent between a pharmaceutical industry relationship and the reported calibration performance of fracture risk assessment instruments. Eight studies had at least one author who was involved in the development of the risk assessment instrument evaluated [9, 10, 13–15, 17, 18, 22]; no clear relationship was apparent between having an author who was involved in risk tool development and reported instrument calibration performance.

A similar proportion of studies that used methods of medical records review to identify fractures reported good risk assessment instrument calibration compared with studies that assessed fractures by participant self-report. Half of included studies were missing data on at least one instrument clinical risk factor, and used substituted data for the missing information [9, 10, 12–16, 21]; a higher proportion of these studies reported good instrument calibration compared with studies that were not missing instrument risk factor data. Most studies used estimation methods (Kaplan–Meier estimates) to estimate observed fracture probabilities over the follow-up period of interest in the absence of follow-up over the entire fracture prediction period of interest for all study participants; however, four studies did not use estimation methods due to performing their analyses on subjects for whom data on fracture outcomes was available for the entire fracture risk prediction period of interest [12, 17, 19, 22]; three of these studies reported suboptimal risk assessment instrument calibration.

Discussion

This systematic review of the performance of osteoporosis clinical fracture risk assessment instruments for predicting absolute future fracture risk in populations other than their development cohorts found that relatively few studies have been performed to date to externally validate the performance of fracture risk assessment instruments, and these studies are heterogeneous in terms of assessing a variety of risk assessment instruments in different patient populations. Of the studies that have been done, findings are mixed with respect to how well instruments perform in terms of observed fracture probabilities matching predicted fracture probabilities, i.e., calibration. Additionally, many of the studies that have assessed the calibration of fracture risk assessment instruments have methodological features making them susceptible to bias, which makes interpretation of their findings more difficult. A recent paper by Kanis et al. highlighted several methodological flaws in some external validation studies of FRAX [47], for example not incorporating the death hazard when assessing the tool's performance. FRAX was the only risk assessment instrument for which we found more than two studies assessing calibration in populations unrelated to the development cohorts—and the studies that evaluated this instrument found mixed performance results. Two of the studies assessing FRAX instrument calibration were performed in one country, Canada; however, both of these studies assessed FRAX's performance in one clinical referral population cohort, the Manitoba BMD cohort—which makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the generalizability of these findings for the general Canadian population [10, 14]. One large study that evaluated the performance of QFractureScores in a nationally representative cohort in the UK found good calibration of this risk assessment instrument [21], providing compelling evidence that this instrument is well calibrated for the general population of the UK. Findings on the performance of other evaluated risk instruments were limited and mixed.

We are not aware of any prior comprehensive systematic review that has assessed the performance of osteoporosis absolute fracture risk assessment instruments by comparing predicted fracture probabilities to observed fracture probabilities (i.e., calibration) in populations other than the risk instrument development cohorts. A more general review on prognostic instruments to identify patients at risk for osteoporotic fractures by Steurer et al. in 2011 [48] highlighted that there have been few validation studies of prognostic instruments to identify patients at risk for osteoporotic fractures, and significant heterogeneity in study characteristics, prediction variables, outcome assessment, and follow-up time periods; however, the review by Steurer et al. excluded the FRAX instrument. Additionally, another recent systematic review of the literature on fracture risk assessment instruments assessed another measure of their performance, specifically their ability to discriminate individuals who fracture from those who do not (i.e., discrimination), using area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) as the performance outcome measure of interest [49]. The prior systematic review done by Nelson et al. in 2010 was part of an evidence update relevant to screening for osteoporosis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and identified eleven studies that reported AUCs for fracture prediction for 11 different risk instruments; AUCs varied from 0.48 to 0.89 [49]. The authors concluded that risk assessment instruments are modest predictors of fracture. Additionally, Nelson et al. found that simple models containing only a few clinical variables performed as well as more complex instruments for fracture prediction [49]. Our study, which compared predicted vs. observed fracture probabilities for risk assessment instruments, provides a different measure of the performance of these instruments—how well calibrated they are. AUCs, although they provide a useful comparison for overall instrument performance in terms of discriminating individuals who fracture from those who do not (i.e., discrimination), do not provide information on risk assessment instrument performance in terms of calibration at specific risk thresholds/categories—which is essential information for a clinician to know when using an instrument [50]. Thus, our findings complement those of the review by Nelson et al. in summarizing the evidence on a different and important measure of the performance of fracture risk assessment instruments. Similar to Nelson et al., our findings indicate mixed performance results for different risk assessment instruments evaluated in various study populations; albeit for a difference measure of instrument performance (calibration rather than discrimination).

Several recent studies that have used AUCs as a performance measure have suggested that simple risk assessment instruments perform as well as more complex instruments for predicting future fracture risk [12, 49, 51]. Our study found that a slight majority of the relatively simple risk assessment instruments (which we defined as five or less clinical variables) evaluated were found to have good calibration, similar to the proportion of complex risk assessment instruments evaluated that were found to have good calibration. We also found no clear differences in the proportion of risk assessment instruments with a BMD component versus those without a BMD component that were found to have good versus poor calibration. Thus, our findings with respect to calibration provide further evidence that simple risk assessment instruments may perform as well as complex instruments; or at least that the literature does not provide compelling evidence that complex risk assessment instruments are necessarily better calibrated than simple instruments. However, it is important to note that although simple risk assessment instruments may perform similarly to complex instruments for a population in which the prevalence of secondary causes of osteoporosis (e.g., prolonged glucocorticoid use) is low, for individuals with secondary causes of osteoporosis these tools will likely not perform as well; such individuals would likely benefit from use of a complex risk assessment instrument.

Our systematic review highlights that conclusive evidence is lacking with respect to the external validity of available fracture risk assessment instruments for predicting future fracture risk in different patient populations in which they may be used. Few studies have been done to assess the external validity of fracture risk assessment instruments, and there are a number of potential sources of bias in most studies that have been done. Despite the dearth of studies demonstrating calibration and external validity of these instruments, they are growing in clinical use and several guidelines groups have recommended their use [8]. More high-quality studies are needed to assess the performance of osteoporosis fracture risk assessment instruments in terms of their calibration in cohorts independent of their development cohorts, in populations representative of those in which they may be used, so that physicians and patients can be confident in their use to make clinical care decisions. Further studies would also help to identify best performing instruments in different patient populations. Additionally, more studies need to be done to assess the performance of risk assessment instruments in men, for whom there is a particular dearth of evidence.

Our study has several limitations. Although we performed an exhaustive literature search, we may have missed some relevant citations, particularly those that were published after our literature search was performed. Additionally, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis of the included studies due to considerable study heterogeneity in key characteristics. Furthermore, the studies included in our systematic review assessed the performance of risk assessment instruments in cohorts from which data on fracture outcomes was primarily collected in the 1990s and the early 2000s, and may not reflect the exact performance of these risk assessment instruments today—as osteoporotic fracture rates are changing over time [52–54], the performance of risk assessment instruments would be expected to change, and the calibration of the instruments would need to be reassessed. In addition, we included studies that included patients on osteoporosis therapy that can reduce fracture risk, which may alter the observed risk. Our study also had several notable strengths. We performed an exhaustive literature search for studies that evaluated the performance of fracture risk assessment instruments by comparing predicted fracture probability to observed fracture probability. We are not aware of any other comprehensive systematic review of the calibration of fracture risk assessment instruments.

In conclusion, our systematic review found that relatively few studies have been done that assess the calibration of fracture risk assessment instruments in populations separate from their development cohorts; of the studies that have been done on this topic, findings are mixed with respect to risk assessment instrument performance, and many studies have methodological limitations that make susceptibility to bias a concern. Further high-quality studies to assess the calibration of risk assessment instruments in populations in which they may be used are needed before the widespread use of individual risk assessment instruments can be recommended.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals who kindly provided requested data from their papers: MJ Bolland, GS Collins, E Czerwinski, B Ettinger, DA Hanley, A Kumorek, WD Leslie, L Langsetmo, and J Tamaki.

Sources of funding Smita Nayak was supported by grant 7R01AR060809-03 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; Susan L. Greenspan was supported by NIH grants P30AG024827 and R01AG028068-01A2.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest None.

Contributor Information

S. Nayak, Swedish Center for Research and Innovation, Swedish Health Services, Swedish Medical Center, 747 Broadway, Seattle, WA 98122-4307, USA

D. L. Edwards, Swedish Center for Research and Innovation, Swedish Health Services, Swedish Medical Center, 747 Broadway, Seattle, WA 98122-4307, USA

A. A. Saleh, Arizona Health Sciences Library, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

S. L. Greenspan, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

References

- 1.Lin JT, Lane JM. Osteoporosis: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:126–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465–475. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacDermid JC, Roth JH, Richards RS. Pain and disability reported in the year following a distal radius fracture: a cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; Rockville: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stafford RS, Drieling RL, Hersh AL. National trends in osteoporosis visits and osteoporosis treatment, 1988–2003. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1525–1530. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen TV, Center JR, Eisman JA. Osteoporosis: underrated, underdiagnosed and undertreated. Med J Aust. 2004;180:S18–S22. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb05908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Osteoporosis is markedly underdiagnosed: a nationwide study from Denmark. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:134–141. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leslie WD, Schousboe JT. A review of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment options in new and recently updated guidelines on case finding around the world. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2011;9:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s11914-011-0060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Staa TP, Geusens P, Kanis JA, Leufkens HG, Gehlbach S, Cooper C. A simple clinical score for estimating the long-term risk of fracture in post-menopausal women. QJM. 2006;99:673–682. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leslie WD, Berger C, Langsetmo L, Lix LM, Adachi JD, Hanley DA, Ioannidis G, Josse RG, Kovacs CS, Towheed T, Kaiser S, Olszynski WP, Prior JC, Jamal S, Kreiger N, Goltzman D. Construction and validation of a simplified fracture risk assessment tool for Canadian women and men: results from the CaMos and Manitoba cohorts. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1873–1883. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1445-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolland MJ, Siu AT, Mason BH, Horne AM, Ames RW, Grey AB, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Evaluation of the FRAX and Garvan fracture risk calculators in older women. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:420–427. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamaki J, Iki M, Kadowaki E, Sato Y, Kajita E, Kagamimori S, Kagawa Y, Yoneshima H. Fracture risk prediction using FRAX(R): a 10-year follow-up survey of the Japanese Population-Based Osteoporosis (JPOS) Cohort Study. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:3037–3045. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1537-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo JC, Pressman AR, Chandra M, Ettinger B. Fracture risk tool validation in an integrated healthcare delivery system. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:188–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leslie WD, Lix LM, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey E, Kanis JA. Independent clinical validation of a Canadian FRAX tool: fracture prediction and model calibration. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2350–2358. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langsetmo L, Nguyen TV, Nguyen ND, Kovacs CS, Prior JC, Center JR, Morin S, Josse RG, Adachi JD, Hanley DA, Eisman JA. Independent external validation of nomograms for predicting risk of low-trauma fracture and hip fracture. CMAJ. 2011;183:E107–114. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Predicting risk of osteoporotic fracture in men and women in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QFractureScores. BMJ. 2009;339:b4229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ettinger B, Hillier TA, Pressman A, Che M, Hanley DA. Simple computer model for calculating and reporting 5-year osteoporotic fracture risk in postmenopausal women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14:159–171. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leslie WD, Lix LM. Simplified 10-year absolute fracture risk assessment: a comparison of men and women. J Clin Densitom. 2010;13:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abrahamsen B, Vestergaard P, Rud B, Barenholdt O, Jensen JE, Nielsen SP, Mosekilde L, Brixen K. Ten-year absolute risk of osteoporotic fractures according to BMD T score at menopause: the Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:796–800. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.020604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leslie WD, Tsang JF, Lix LM. Validation of ten-year fracture risk prediction: a clinical cohort study from the Manitoba Bone Density Program. Bone. 2008;43:667–671. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins GS, Mallett S, Altman DG. Predicting risk of osteoporotic and hip fracture in the United Kingdom: prospective independent and external validation of QFractureScores. BMJ. 2011;342:d3651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Czerwinski E, Kanis JA, Osieleniec J, Kumorek A, Milert A, Johansson H, McCloskey EV, Gorkiewicz M. Evaluation of FRAX to characterise fracture risk in Poland. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2507–2512. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1502-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmed LA, Schirmer H, Fønnebø V, Joakimsen RM, Berntsen GK. Validation of the Cummings' risk score; How well does it identify women with high risk of hip fracture: The Tromsø Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(11):815–822. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azagra R, Roca G, Encabo G, Prieto D, Aguye A, Zwart M, Guell S, Puchol N, Gene E, Casado E, Sancho P, Sola S, Toran P, Iglesias M, Sabate V, Lopez-Exposito F, Ortiz S, Fernandez Y, Diez-Perez A. Prediction of absolute risk of fragility fracture at 10 years in a Spanish population: validation of the WHO FRAX TM tool in Spain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Body JJ, Moreau M, Bergmann P, Paesmans M, Dekelver C, Lemaire ML. Absolute risk fracture prediction by risk factors validation and survey of osteoporosis in a Brussels cohort followed during 10 years (FRISBEE study). Rev Med Brux. 2008;29(4):289–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung EYN, Bow CH, Cheung CL, Soong C, Yeung S, Loong C, Kung A. Discriminative value of FRAX for fracture prediction in a cohort of Chinese postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:871–878. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colon-Emeric CS, Pieper CF, Artz MB. Can historical and functional risk factors be used to predict fractures in community-dwelling older adults? Development and validation of a clinical tool. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13(12):955–961. doi: 10.1007/s001980200133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Laet CE, Van Hout BA, Burger H, Weel AE, Hofman A, Pols HA. Hip fracture prediction in elderly men and women: validation in the Rotterdam study. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(10):1587–1593. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.10.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durosier C, Hans D, Krieg MA, Schott AM. Defining risk thresholds for a 10-year probability of hip fracture model that combines clinical risk factors and quantitative ultrasound: results using the EPISEM cohort. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11(3):397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ensrud KE, Lu LY, Taylor BC, Schousboe JT, Donaldson MG, Fink HA, Cauley JA, Hillier TA, Browner WS, Cummings SR, Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research, Group A comparison of prediction models for fractures in older women: is more better? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2087–2094. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujiwara S, Hamaya E, Goto W, Masunari N, Furukawa K, Fukunaga M, Nakamura T, Miyauchi A, Chen P. Vertebral fracture status and the World Health Organization risk factors for predicting osteoporotic fracture risk in Japan. Bone. 2011;49:520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]