Abstract

Background

Mobile technologies have wide-scale reach and disseminability, but no known studies have examined mobile technologies as a stand-alone tool to improve obesity-related behaviors of at-risk youth.

Purpose

To test a 12-week mobile technology intervention for use and estimate effect sizes for a fully powered trial.

Methods

Fifty-one low-income, racial/ethnic minority girls aged 9–14 years were randomized to a mobile technology (n=26) or control (n=25) condition. Both conditions lasted 12 weeks and targeted fruits/vegetables (FV; weeks 1–4), sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB; weeks 5–8), and 2 screen time (weeks 9–12). The mobile intervention prompted real-time goal setting and self-monitoring and provided tips, feedback, and positive reinforcement related to the target behaviors. Controls received the same content in a written manual but no prompting. Outcomes included device utilization and effect sizes estimates of FV, SSB, screen time, and BMI. Data were collected and analyzed in 2011–2012.

Results

Mobile technology girls used the program on 63% of days and exhibited trends toward increased FVs (+0.88, p=0.08) and decreased SSBs (−0.33, p=0.09). The adjusted difference between groups of 1.0 servings of FV (p=0.13) and 0.35 servings of SSB (p=0.25) indicated small to moderate effects of the intervention (Cohen’s d=0.44 and −0.34, respectively). No differences were observed for screen time or BMI.

Conclusions

A stand-alone mobile app may produce small to moderate effects for FV and SSB. Given the extensive reach of mobile devices, this pilot study demonstrates the need for larger-scale testing of similar programs to address obesity-related behaviors in high-risk youth.

Introduction

Preventing obesity is a priority for all children, but is especially important for racial/ethnic minority and low-income youth who are at highest risk.1,2 In-person interventions comprise the majority of current obesity prevention approaches, but are limited in their cost, sustainability, long-term effectiveness, and reach/disseminability.3,4 Mobile technologies (e.g., smartphones and tablets) have potential for wide-scale reach even among racial/ethnic minority and low-income youth who are just as likely as higher income, white youth to have mobile access through phones and tablets.5,6

While studies suggest that youth like mobile apps for improving their nutrition and activity patterns,7–10 few have examined whether these applications are effective at changing behavior. In addition, the majority of studies have focused on mobile applications as an adjunct to weight loss treatment.9–12 Only one focused on obesity prevention in children across the weight spectrum,8 and no known studies have examined mobile applications as a stand-alone, minimal-contact childhood obesity prevention tool. The purpose of this randomized pilot trial was to test the feasibility and potential efficacy of a 12-week stand-alone mobile technology intervention. The pilot study was not designed to have sufficient power to test for between-group differences, but rather to determine effect size estimates for a fully powered trial.

Methods

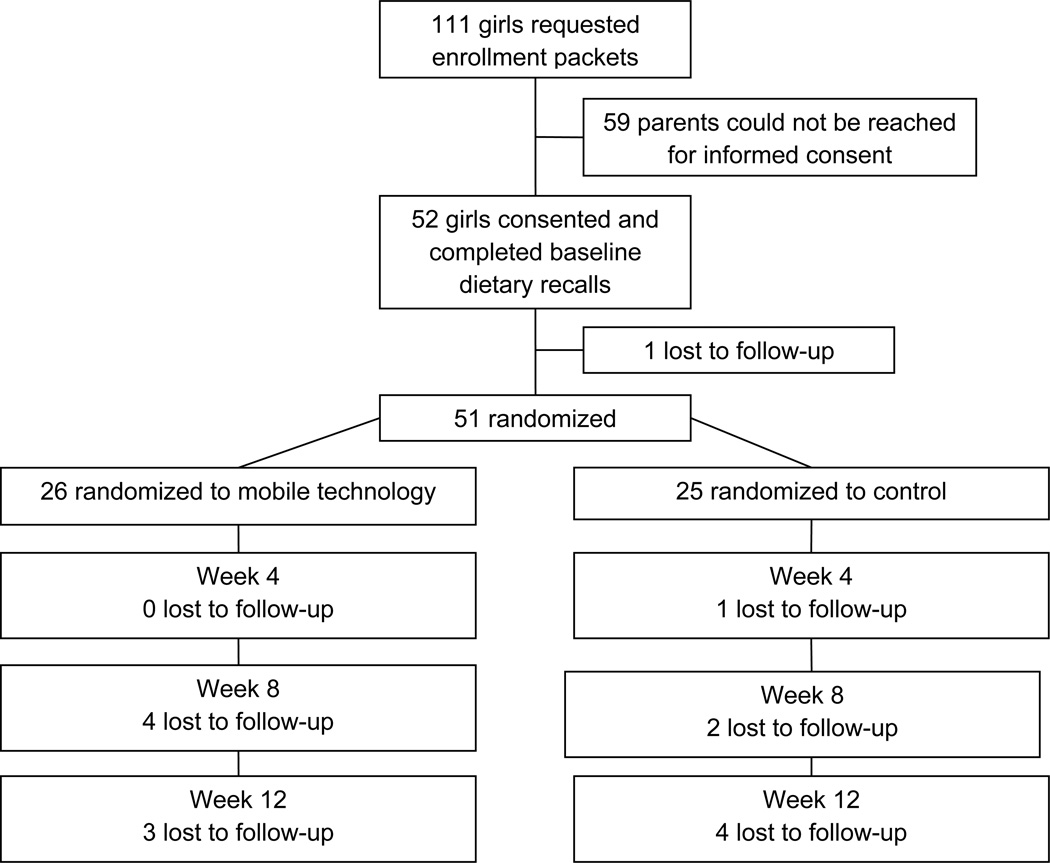

Fifty-one girls were recruited through afterschool programs located in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods and were randomly assigned to a mobile technology (MT; n=26) or control (n=25) condition. Girls aged 9–14 years who were members of the after school program and able to speak/read English and comprehend the program were eligible. Parents gave written informed consent, and girls provided assent. Study procedures were approved by the IRB of the University of Kansas School of Medicine. Participants were randomized between March 2011 and April 2012. Follow-up was completed in July 2012.

Intervention

Both conditions included three 4-week modules that targeted fruits/vegetables (FV; weeks 1–4), sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB; weeks 5–8), and screen time (weeks 9–12).

The MT intervention was delivered on aMyPal A626 handheld computer (ASUS Computer International, usa.asus.com). The device was comparable in size, weight, and appearance to a smartphone and used a Microsoft Windows Mobile 6 operating system. The intervention was grounded in behavioral weight control principles13,14 and developed through extensive formative research that has been described in detail elsewhere.7 In brief, it included goal-setting and planning that required girls to set two daily goals and an accompanying plan for improving the behavior addressed in each module, cues to action and self-monitoring that prompted girls to self-monitor progress toward their goals at five preselected times throughout the day, and feedback and reinforcement on goal-attainment. Use was reinforced through a song-based reward system that provided girls one song per day if they responded to 80% of daily prompts. In an attempt to discourage use of the program beyond the required goal-setting and self-monitoring components, the intervention was intentionally designed without gaming, social media, or text messaging formats that could promote rather than diminish screen time.

Girls randomized to the control condition received manuals at weeks 1 (FV), 5 (SSB), and 9 (screen time). Manuals were comprised of screen shots from each respective module and were identical in content to MT. Unlike MT, the control condition relied on girls to initiate goal-setting, planning, and self-monitoring and did not include action cues or a reward system.

Measures

Girls provided their date of birth, race/ethnicity, and home availability of FV, SSB, and screen time-related devices using standard questions.15–18 The 2010 U.S. Census was used to obtain objective indicators of SES for the Census Tract Area where girls lived.19,20 Use of the MT was obtained from time- and date-stamped records on each handheld computer. FV (baseline and week 4) and SSB (baseline and week 8) were assessed using the standardized 24-hour dietary recall multiple pass method and summarized according to the 2-day means.21–23 One weekday and one weekend recall were collected from >94% of participants. Screen time was measured at baseline and week 12 using the Brief Questionnaire of Television Viewing and Computer Use.24 Height and weight were measured without shoes, socks, or outerwear.

Statistical Analyses

Associations between MT use and behavior change were analyzed using the Generalized Linear Models procedure. Between- and within-group change was compared across groups using an independent sample t-test and paired samples t-test, respectively. Effect size estimates were calculated as the difference in between-group change divided by the pooled SED for each outcome variable.25

Results

Demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Forty-four girls (86.2%) completed week 12. The seven girls lost to follow-up (four MT and three control) did not differ from the 44 completers on baseline age, BMI, total energy, or percentage of calories obtained from fat.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics*

| Construct | Total (n=51) |

Mobile technology (n=26) |

Control (n=25) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 11.3 (1.6) | 11.3 (1.5) | 11.3 (1.7) | |||

| Race, % | ||||||

| African American | 83.7 | 80.8 | 86.9 | |||

| Bi- or Multi-racial | 8.2 | 11.5 | 4.4 | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 6.1 | 7.7 | 4.4 | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.0 | 0.0 | 4.4 | |||

| Ethnicity, % | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latina | 7.8 | 7.7 | 8.0 | |||

| Neighborhood Economic Disadvantage | ||||||

| % Children living in poverty, mean (SD) | 32.4 (16.5) | 33.4 (17.3) | 31.4 (16.2) | |||

| Median annual household income, mean (SD) | $27,388 ($11,196) | $27,854 ($13,992) | $26,900 ($7,552) | |||

| Adults with bachelor degree or above (%) | 5.7 | 6.9 | 4.3 | |||

| Anthropometry, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Height in inches | 59.8 (4.0) | 60.0 (4.1) | 59.5 (3.8) | |||

| Weight in pounds | 120.6 (31.6) | 114.9 (26.2) | 126.8 (36.1) | |||

| BMI | 23.7 (5.7) | 22.5 (4.8) | 25.0 (6.3) | |||

| BMI percentile, %a | ||||||

| <85th | 20.0 | 12.0 | 8.0 | |||

| 85th to <95th | 8.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | |||

| ≥95th | 22.0 | 9.0 | 13.0 | |||

| Dietary intake, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Total energy, kcal | 1,610.3 (597.6) | 1708.1 (658.9) | 1,508.6 (520.2) | |||

| % calories from fat | 35.9 (6.2) | 36.4 (6.5) | 35.4 (5.9) | |||

| Home availability | ||||||

| Fruit available at home, % “never” or “sometimes” | 49.0 | 46.2 | 52.0 | |||

| Vegetables available at home, % “never” or “sometimes” | 29.4 | 23.1 | 36.0 | |||

| Number of SSBs available at home, mean (SD) | 3.0 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.0) | |||

| Fruit drinks/punches, % | 74.5 | 80.8 | 68.0 | |||

| Kool-aid, % | 68.6 | 73.1 | 64.0 | |||

| Non-diet soda, % | 54.0 | 60.0 | 48.0 | |||

| Sweetened tea, % | 47.1 | 50.0 | 44.0 | |||

| Sports drinks, % | 33.3 | 42.3 | 24.0 | |||

| Energy drinks, % | 20.0 | 16.0 | 24.0 | |||

| Number of screen devices at home, mean (SD) | 10.8 (3.9) | 11.3 (3.6) | 10.2 (4.2) | |||

| Televisions | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.4 (1.0) | |||

| Cell phones | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.3 (0.8) | |||

| DVD players | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.0) | 1.8 (1.0) | |||

| Video game consoles | 1.3 (1.1) | 2.0 (0.7) | 1.1 (1.1) | |||

| Computers | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.2 (0.9) | 1.5 (1.0) | |||

There are no statistically differences between groups in any of the baseline demographic characteristics

Calculated using CDC growth charts

DVD, digital video disc

The average rating of MT program enjoyment was 4.5 (SD=0.9). Favorite parts of the MT program were obtaining songs (68.2%) and setting goals (36.4%). The least favorite part of the program was the reminder prompts (31.8%). Girls used the program on 63% of days, responded to 42% of prompts, and earned an average of 23.9 songs (www.ajpmonline.org). A significant association was found between MT use and SSB (r=0.50, p=0.01). Girls responding to more prompts showed greater reductions in SSB at week 8 compared those responding to fewer 6 prompts (mean difference, −0.31 daily servings). No significant associations were seen between MT utilization and FV or screen time-related behaviors.

MT girls exhibited trends toward increased FVs (+0.88, p=0.08) and decreased SSBs (−0.33, p=0.09) (Table 2). The adjusted difference between groups of 1.0 servings of FV (p=0.13) and 0.35 servings of SSB (p=0.25) was not statistically significant but indicated small to moderate effects of the intervention (Cohen’s d=0.44 and −0.34, respectively). No statistically significant differences were observed for screen time or BMI.

Table 2.

Change from baseline in behavioral outcomes by treatment group

| Variable | Group | Time point | Effect size* |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Group |

Within group |

||||||

| Baseline Mean (SD) | Week 4 Mean (SD) | ΔBL to week 4 Mean (SD) | |||||

| Fruits and vegetables, daily servingsa | MT | 2.53 (1.45) | 3.35 (1.81) | 0.88 (2.36) | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| Control | 2.34 (1.55) | 2.32 (1.73) | −0.12 (2.16) | 0.79 | |||

| Baseline Mean (SD) | Week 8 Mean (SD) | ΔBL to week 8 Mean (SD) | |||||

| Sugar-sweetened beverages, daily servingsb | MT | 1.20 (0.92) | 0.87 (0.93) | −0.33 (0.93) | −0.34 | 0.25 | 0.09 |

| Control | 0.95 (0.87) | 1.05 (0.85) | 0.02 (1.14) | 0.94 | |||

| Baseline Mean (SD) | Week 12 Mean (SD) | ΔBL to week 12 Mean (SD) | |||||

| Screen time, hours per day | MT | 3.36 (2.30) | 3.72 (2.44) | 0.32 (2.32) | 0.09 | 0.76 | 0.53 |

| Control | 3.72 (2.28) | 3.77 (1.99) | 0.12 (2.05) | 0.80 | |||

| Baseline Mean (SD) | Week 12 Mean (SD) | ΔBL to week 12 Mean (SD) | |||||

| BMI | MT | 22.47 (4.79) | 22.55 (4.56) | −0.21 (2.20) | 0.03 | 0.91 | 0.66 |

| Control | 25.03 (6.33) | 24.50 (5.93) | −0.27 (1.17) | 0.33 | |||

Cohen’s d in between group change for each outcome variable. Values of 0.80, 0.50, and 0.20 distinguish large, medium, and small effects.

Estimates of daily servings of fruits and vegetables included 100% fruit juice but excluded French fries and other fried potatoes.

Sugar-sweetened beverages were defined as non-diet sodas, fruit drinks and/or punches, sweetened teas, sports or energy drinks, and sweetened coffee drinks.

BL, baseline; MT, mobile technology

Discussion

This is the first known study to examine whether a stand-alone mobile app is effective at changing nutrition and activity behaviors in youth. Results are promising for FV and SSB, with girls in the MT group consuming 1.0 more daily servings of FV and 0.35 fewer daily servings of SSB than girls in the control group. These improvements are equivalent or higher to those found for intensive, in-person studies17,26,27 and are especially important considering the large-scale reach and disseminability of mobile interventions.28

The intervention had no noticeable impact on BMI or screen time, although changes in BMI would not be expected over 12 weeks when weight loss is not addressed. All girls received the screen time intervention last and use declined over time. By week 12, girls used the program on only 48% of days, suggesting that the reward system had lost its appeal. Immediate reinforcement after each prompt in combination with access to a wider selection of songs may increase use and, subsequently, effect sizes, but should be tested in a larger trial. In addition, 7 girls attended the program after school and, anecdotally, they chose computers/social media over exercise. They returned to homes with an average of 11 screen devices and lived in economically deprived neighborhoods where safety and playing outside were likely issues. Additional strategies, including interventions that address environmental barriers, may be warranted to decrease screen time in this population.

Results should be interpreted with caution given the small sample size and the program’s focus on short-term behavior change. While the results are promising for FV and SSB, maintenance of these behaviors and impact on BMI should be examined in a fully powered trial of a longer duration. The reward system was intrinsically linked to the mobile application and it is impossible to separate the reward component from other components of the program. Finally, while the usage rates obtained in this study compare favorably to similar studies,7,8,11,12 maintaining long-term interest in technology-delivered applications remains a challenge and is an important area for future study.

Conclusions

A stand-alone mobile app may produce small to moderate effects for FV and SSB. Given the extensive reach of mobile devices, this pilot study demonstrates the need for larger-scale testing of similar programs to address obesity-related behaviors in high-risk youth.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Acknowledgments

Dr. Nollen was supported by an award that was co-funded by the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) (K12 HD052027) and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute at the NIH (K23 HL090496). The views expressed in this paper do not reflect those of the NIH. We are grateful to Marilyn Ault, Melanie Farmer, Jane Adams, Jason Kroge, David Scherrer, and Phuong Tran of Advanced Learning Technologies in Education Consortia (ALTEC) at the Center for Research on Learning at the University of Kansas for their software programming and artwork, and Xinhua Zhou for data analysis assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Rising social inequalities in U.S. childhood obesity, 2003–2007. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(1):40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kesten JM, Griffiths PL, Cameron N. A systematic review to determine the effectiveness of interventions designed to prevent overweight and obesity in pre-adolescent girls. Obes Rev. 2011;12(12):997–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenhart A. Teens, smartphones, and texting. Washington DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2012. www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Teens-and-smartphones.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madden M, Lenhart A, Duggan M, Cortesi S, Gasser U. Teens and Technology 2013. Washington DC: Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project; 2013. www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Teens-and-Tech.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nollen NL, Hutcheson T, Carlson S, et al. Development and functionality of a handheld computer program to improve fruit and vegetable intake among low-income youth. Health Educ Res. 2013;28(2):249–264. doi: 10.1093/her/cys099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro JR, Bauer S, Hamer RM, Kordy H, Ward D, Bulik CM. Use of text messaging for monitoring sugar-sweetened beverages, physical activity, and screen time in children: a pilot study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;40(6):385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woolford SJ, Barr KL, Derry HA, et al. OMG do not say LOL: obese adolescents’ perspectives on the content of text messages to enhance weight loss efforts. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(12):2382–2387. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolford SJ, Clark SJ, Strecher VJ, Resnicow K. Tailored mobile phone text messages as an adjunct to obesity treatment for adolescents. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16(8):458–461. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.100207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer S, de Niet J, Timman R, Kordy H. Enhancement of care through self-monitoring and tailored feedback via text messaging and their use in the treatment of childhood overweight. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(3):315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Niet J, Timman R, Bauer S, et al. The effect of a short message service maintenance treatment on body mass index and psychological well-being in overweight and obese children: a randomized trial. Pediatric Obesity. 2012;7(3):205–219. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Smith SP. Using goal setting as a strategy for dietary behavior change. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(5):562–566. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foreyt JP, Poston WS., 2nd The role of the behavioral counselor in obesity treatment. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98(10) Suppl 2:S27–S30. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(98)00707-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Atlanta GA: CDC; 2011. www.cdc.gov/yrbs. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, et al. Fit for Life Boy Scout badge: outcome evaluation of a troop and Internet intervention. Prev Med Mar. 2006;42(3):181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Story M, Sherwood NE, Himes JH, et al. An after-school obesity prevention program for African-American girls: the Minnesota GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(1) Suppl 1:S54–S64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson D, Baranowski T, Baranowski J, et al. Boy Scout 5-a-Day Badge: outcome results of a troop and Internet intervention. Prev Med. 2009;49(6):518–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Everson-Rose SA, Skarupski KA, Barnes LL, Beck T, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF. Neighborhood socioeconomic conditions are associated with psychosocial functioning in older black and white adults. Health Place. 2011;17(3):793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendzor DE, Reitzel LR, Mazas CA, et al. Individual- and area-level unemployment influence smoking cessation among African Americans participating in a randomized clinical trial. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(9):1394–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford PB, Obarzanek E, Morrison J, Sabry ZI. Comparative advantage of 3-day food records over 24-hour recall and 5-day food frequency validated by observation of 9- and 10-year-old girls. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94(6):626–630. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson RK, Driscoll P, Goran MI. Comparison of multiple-pass 24-hour recall estimates of energy intake with total energy expenditure determined by the doubly labeled water method in young children. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96(11):1140–1144. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Resnicow K, Odom E, Wang T, et al. Validation of three food frequency questionnaires and 24-hour recalls with serum carotenoid levels in a sample of African-American adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(11):1072–1080. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.11.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitz KH, Harnack L, Fulton JE, et al. Reliability and validity of a brief questionnaire to assess television viewing and computer use by middle school children. J Sch Health. 2004;74(9):370–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beech BM, Klesges RC, Kumanyika SK, et al. Child- and parent-targeted interventions: the Memphis GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(1) Suppl 1:S40–S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klesges RC, Obarzanek E, Kumanyika S, et al. The Memphis Girls’ health Enrichment Multi-site Studies (GEMS): an evaluation of the efficacy of a 2-year obesity prevention program in African American girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(11):1007–1014. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Vogt TM. Evaluating the impact of health promotion programs: using the RE-AIM framework to form summary measures for decision making involving complex issues. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(5):688–694. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]