Abstract

Intestinal homeostasis is maintained by a hierarchy of immune defenses acting in concert to minimize contact between luminal microorganisms and the intestinal epithelial cell surface. The intestinal mucus layer, covering the gastrointestinal tract epithelial cells, contributes to mucosal homeostasis by limiting bacterial invasion. In this study, we used γδ T-cell-deficient (TCRδ−/−) mice to examine whether and how γδ T-cells modulate the properties of the intestinal mucus layer. Increased susceptibility of TCRδ−/− mice to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis is associated with a reduced number of goblet cells. Alterations in the number of goblet cells and crypt lengths were observed in the small intestine and colon of TCRδ−/− mice compared with C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice. Addition of keratinocyte growth factor to small intestinal organoid cultures from TCRδ−/− mice showed a marked increase in crypt growth and in both goblet cell number and redistribution along the crypts. There was no apparent difference in the thickness or organization of the mucus layer between TCRδ−/− and WT mice, as measured in vivo. However, γδ T-cell deficiency led to reduced sialylated mucins in association with increased gene expression of gel-secreting Muc2 and membrane-bound mucins, including Muc13 and Muc17. Collectively, these data provide evidence that γδ T cells play an important role in the maintenance of mucosal homeostasis by regulating mucin expression and promoting goblet cell function in the small intestine.

Keywords: intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, T cell receptor-γδ, mouse mucin

the mammalian gastrointestinal (GI) tract contains a dynamic community of trillions of microorganisms (25). These microorganisms establish a symbiotic relationship with the host, making essential contributions to mammalian metabolism while occupying a protected, nutrient-rich environment (40). However, the close association of a dense bacterial community with intestinal tissues poses a serious risk to the host. Several immune mechanisms must work in concert to limit commensals exposure to the epithelial surface (25).

Mucus covering the GI tract forms the first line of immune defense, providing a barrier through the secretion of mucins, antimicrobial proteins (AMPs) and immunoglobulin A (IgA). The thickness of the mucus layer varies along the GI tract, correlating with the microbial burden found in the respective GI regions (21). The mucus layer is composed of two layers: a firm inner layer and a loose outer layer (2). In the colon, the firmly attached stratified inner layer has been shown to exclude a majority of the bacteria, whereas the loose outer layer serves as a habitat for the intestinal commensal microbiota (13, 36). The secreted mucins are continuously produced by specialized goblet cells that are found in large numbers in the intestinal epithelium (37, 38). Muc2 is the most abundantly expressed secretory mucin in the colon and the small intestine (SI) and constitutes the structural component of the mucus layer. The importance of the mucus barrier stemmed from studies showing that mice deficient in Muc2 develop spontaneous chronic intestinal inflammation (36, 63). In addition, missense mutations in the Muc2 gene, leading to aberrant Muc2 oligomerization and glycosylation, result in decreased barrier function leading to ulcerative colitis (UC)-like chronic inflammation in mice (23), which resembles the morphological and inflammatory changes observed in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Both secreted and cell-surface mucins provide a barrier to potential pathogens (44). Deficiency in the Muc1 cell-surface mucin predisposes mice to intestinal infection (42). Mice deficient in cell-surface Muc13 develop more severe acute colitis in response to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) (57). Mucins are decorated with a dense array of complex O-linked carbohydrates assembled by the sequential action of glycosyltransferases (GTs). The synthesis of mucin oligosaccharides starts with the transfer of N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) to serine (Ser) or threonine (Thr) residues of the mucin core. The oligosaccharides may be extended with galactose (Gal), N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), GalNAc, fucose, or sialic acid (Neu5Ac) (45). Aberrant intestinal mucin expression or glycosylation are also associated with chronic inflammation or colon cancer in humans (56) and susceptibility to colitis in mouse models (1, 17, 59). These studies show that a functional mucus layer is essential to maintain an homeostatic relationship with the microbiota and that changes in mucin biosynthesis may disrupt this protective role. In addition, several pathogens have evolved specific strategies for penetrating mucus to gain access to the epithelial cell surface (44).

A second level of immune protection is provided by a large population of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), with one IEL for every 5–10 epithelial cells (14). IELs bearing the γδ T cell receptor are strategically intercalated between epithelial cells on the basolateral side of the intestinal tight junction barrier and thus ideally positioned to defend against invading bacteria. Although γδ IELs constitute the majority of IELs, up to 60% of IELs in the SI (7), their functions remain poorly understood. Some studies have shown that γδ IELs contribute to the progression of immune-mediated colitis (46, 47); other data suggested that γδ IELs contribute to epithelial restitution following injury (6, 28, 39) by secreting keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) (5, 6) and AMPs (29, 30) during the inflammatory response. The role of γδ IELs in promoting barrier maintenance has been demonstrated by using DSS-treated mice deficient in γδ T cells, TCRδ−/− (11, 28, 30). Analysis of TCRδ−/− mice indicated that γδ T cells are essential for controlling mucosal penetration of commensal bacteria immediately following DSS-induced damage, suggesting that a key function of γδ IELs is to maintain host-microbial homeostasis following acute mucosal injury (29). γδ T cells were shown to regulate epithelial regeneration through coordinate expression of genes involved in immunoregulation, inflammatory cell recruitment, and antibacterial factors in response to commensal bacteria (microbiota) (29). In the SI, the response of γδ T cells to the microbiota was not only observed in the context of mucosal injury, but also during homeostasis (30). The intestinal microbiota was shown to induce the expression of antimicrobial factors, including antibacterial lectin RegIIIγ in SI γδ T cells, promoting the spatial segregation of the microbiota from the host mucosal surface (62). These studies highlighted a role of γδ IELs as essential mediators of host-microbial homeostasis at the intestinal mucosal surface.

Whether γδ T cells contribute to the maintenance of an intact mucus layer in a homeostatic environment and/or following mucosal injury is currently unknown. In this study we aim to shed light on the role of γδ T cells in modulating mucus expression, organization, and glycosylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General materials.

All chemicals in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise specified. The water used in this study was deionized and ultrapure to a resistance of 18.2 MΩ/cm (Barnsted Nanopure Diamond). All imaging in this study was performed on a Carl Zeiss light microscope.

Animals.

C57Bl/6J wild-type (Harlan Labs) and B6.129P2-Tcrdtm1Mom (TCRδ−/−; Jax Laboratories) mice were bred and maintained at a conventional animal unit at the University of East Anglia. All animals were specific pathogen-free and had access to a standard mouse diet and water ad libitum. For all studies, 10- to 20-wk-old, age- and sex-matched mice were used. C57BL/6 mice were used as wild-type controls. TCRδ−/− mice were used as our immune cell-deficient mouse model that has a neomycin-targeted deletion of 4 kb of the Cδ region (32). All animal experiments were conducted in full accordance with the Animal Scientific Procedures Act 1986 under Home Office approval. The animal experiments conducted at Uppsala University were approved by the Swedish Laboratory Animal Ethical Committee in Uppsala and were conducted in accordance with guidelines of the Swedish National Board for Laboratory Animals.

Induction and assessment of colitis.

Colitis was induced by giving 2.5% DSS (wt/vol, molecular mass 35–50 kDa; MP Biomedicals) in drinking water to age-matched male mice for 7 days. The severity of colitis was assessed daily on the basis of clinical parameters such as stool consistency, fecal blood content (detected with a Hemoccult kit; POCT, Angus, UK), and weight loss. These clinical parameters were scored daily with the use of the disease activity index, a scoring method described in detail by Cooper et al. (9). Colon length was measured macroscopically with a millimeter ruler on the final day of the study, as a further measure of severity of colitis. For histological examination, samples of the distal colon were fixed in 10% formalin, processed, and embedded in wax. Sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and blindly scored to assess epithelial injury [scores 0–3; 0 no injury, 1 focal injury, 2 multifocal injury (>2 areas), 3 diffuse injury (>50% of the circumference)]. For each animal, three sections of the distal colon region were scored.

Periodic acid-Schiff and Alcian blue staining.

Acidic mucins were stained with 1% Alcian blue in 3% acetic acid (pH 2.5) for 15 min, followed by two washes in still tap water. Sections were treated with 0.5% periodic acid for 5 min, followed by a further two washes in still tap water. Neutral mucins were stained with Schiff's reagent for 10 min. Tissue sections were washed thoroughly in still tap water. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. The number of goblet cells per crypt was calculated from an average of 10 crypts per tissue section, for 7 mice. Average crypt lengths (μm) were calculated in a similar manner.

Organoid culture and treatment.

Small intestinal organoids were cultured as previously described (52). Briefly, small intestinal crypts were separated from the epithelium (2 mM EDTA) and cultured in a Matrigel matrix plated out in 24-well tissue culture plates. The complete organoid growth medium (DMEM/F12, Pen/strep, N-acetyl cysteine, EGF, B27, N2, Noggin, R-Spondin 1, and Glutamax) was replaced every 3 days, and confluent organoids were passaged every 7 days. Organoids were stimulated with 100 ng/ml recombinant human KGF (Peprotech) in organoid culture medium for 24 h. Average crypt depth and Muc2-positive goblet cells were calculated for 30 crypts per mouse, for three WT mice and three TCRδ−/− mice. Average number of crypts per organoids was calculated for 10 organoids per mouse for three WT mice and three TCRδ−/− mice.

Fluorescence staining.

Organoids or tissue sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 60 min and blocked for unspecific binding. Primary antibody (chromogranin A 1:200, Abcam; IL-33 1:20, Santa Cruz; lysozyme 1:20, Invitrogen; MUC2 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was applied overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibody was applied for 1 h at room temperature. Lectins (PNA 1:250, Vector Laboratories; WGA 1:250, Vector Laboratories; SNA-I 1:30, Vector Laboratories; MAA 1:20, TCS Biosciences) were applied for 2 h at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1:200, Invitrogen).

In vivo mucus thickness measurements.

Mucus thickness measurements were performed in the Department of Medical Cell Biology at the University of Uppsala, Sweden. Mucus thickness was measured in five separate areas by using a glass micropipette connected to a micromanipulator (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany) with a digimatic indicator (IDC Series 543, Mitutoyo, Tokyo, Japan), at an angle of 30–35° to the cell surface. Briefly, the mice were continuously anesthetized with inhalation gas (2.2% isoflurane, 40% oxygen, and 60% nitrogen) and the body temperature was maintained at 37–38°C. The ileum/distal colon was exteriorized and placed over a truncated cone. A mucosal chamber was fitted over the intestine, exposing the mucosa through a hole in the chamber. The luminal surface of the mucus gel was visualized by placing graphite particles (activated charcoal, extra pure, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) on the gel, and the ileum/distal epithelial cell surface was visible through the stereomicroscope (Leica MZ12, Leica, Heerbrugg, Switzerland). Mucus thickness was measured from the charcoal particle surface to the easily identified surface of the colonic epithelium or to the surface of the epithelium between the villi in the ileum, as previously reported (2). Following measurement of the total mucus thickness, the loose mucus layer was removed by gentle suction. The firm mucus layer was measured immediately following suction. Readings were repeated after 60 min. The mucus thickness (T) was then calculated via the formula T = l × sin a, where l is the measurement made and a is the angle of measurement. Ileum and distal colon mucus thickness was measured in the two groups of mice.

Total RNA extraction.

Small intestine and colon epithelial scrapes from C57BL/6 or TCRδ−/− mice were solubilized in TRI Reagent. RNA was phase separated through the addition of chloroform. After centrifugation, RNA was suspended in isopropanol and centrifuged further. The pellet was rinsed in 70% ethanol and centrifuged, before being resuspended in RNase-free water. Total RNA was extracted from organoids by using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, West Sussex, UK), following the manufacturer's instructions. DNase I treatment and RNA cleanup was performed by using the RNase-free DNase Set and RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer's instructions. The purity, integrity, and quantity of RNA was analyzed by use of a NanoDrop ND-1000 and a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies).

Quantitative PCR.

Total RNA was used to generate cDNA using the Qiagen QuantiTect reverse transcription kit. The quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed by use of the Qiagen QuantiFast SYBRr Green PCR kit and run in an ABI7500 TaqMan thermocycler. All samples were run in triplicate or, where possible, quadruplicate for each gene tested. The results were analyzed using the TaqMan SDS system software and Microsoft Excel. Results are representative of the relative quantitation to 18S RNA by using the formula 2−ΔCt. Primers for the target genes tested are shown in Table 1. Alignment and suitability of the primers were checked with http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/index.cgi?LINK_LOC=BlastHome.

Table 1.

Primer sequences of target genes used for qRT-PCR expression analysis

| Gene | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|

| Reference gene | |

| 18S | F 5′CACGGGAAACCTCACCCGGC3′ |

| R 5′CGGGTGGCTGAACGCCACTT3′ | |

| Mucin genes | |

| Muc1 | F 5′TCCTTGCCCTGGCAGTGTGC3′ |

| R 5′CCGCCAAAGCTGCCCCAAGT3′ | |

| Muc2 | F 5′GGCCTCACCACCAAGCGTCC3′ |

| R 5′TGGGCTGGCAGGTGGGTTCT3′ | |

| Muc3 | F 5′GGTCTTCCATGAAACAGACACAGT3′ |

| R 5′TGAAGGCCAGCCTCAGCAGGA3′ | |

| Muc4 | F 5′TTGCACCTGTCCCCCCTGCCT3′ |

| R 5′GTTCGCCACCGAGGCGTTGA3′ | |

| Muc5AC | F 5′CTGCCCCAAAGGCACCTTCTTAGA3′ |

| R 5′TGGGTGCAGGTGCAAATGGCC3′ | |

| Muc6 | F 5′TGCATGCTCAATGGTATGGT3′ |

| R 5′TGTGGGCTCTGGAGAAGAGT3′ | |

| Muc12 | F 5′GGGACGCTGACCTGCGTGAA3′ |

| R 5′TTGGGGCACACGCATTGGGG3′ | |

| Muc13 | F 5′GCGGTGGAAGCACAGGTCCC3′ |

| R 5′TGCTGACCGTGAAGGGGCTG3′ | |

| Muc17 | F 5′CACACTGGGGCAGAAGGGCG3′ |

| R 5′AGGCAGAGGCACTGGGGTCC3′ | |

| Muc19 | F 5′ACTGGAACCACAGCCAAATC3′ |

| R 5′CTACGGCCTGTTTTTCGGTA3′ | |

| Glycosyltransferase genes | |

| C1GalT1 | F 5′ACTTAGCTCTGGGAAGGTGCATGG3′ |

| R 5′ACAGCATCCAGGACCCTCTATGGGA3′ | |

| C1GalT2 | F 5′TGGAGCCGTTCTAGATGCGGAAAA3′ |

| R 5′GGGGCTTGCAGATGGTGATGCT3′ | |

| C2GnT1 | F 5′GCTTGATAGGAACTTGGCAGCAC3′ |

| R 5′CACCTTCTGGATTTCTTCTGGGTC3′ | |

| C2GnT2 | F 5′ACCTTCACTCCACATCACTCACGG3′ |

| R 5′TTATTCAGCAGAGCCTGGGTCACC3′ | |

| C2GnT3 | F 5′GCCGCTGTTCTTGCTGTTTTG3′ |

| R 5′AGTCACTTGTCATCGCCACGA3′ | |

| C3GnT | F 5′GGCCAGATTCTCCTCTCTCAAACG3′ |

| R 5′AGTGCTCCGCTGTCCAGTCCA3′ | |

| Glyco-genes | |

| IL-33 | F 5′TCCTGTCTGTATTGAGAAACCTGA3′ |

| R 5′TTATGGTGAGGCCAGAACGG3′ | |

| B3GALT5 | F 5′TCACTCACCGGCTGCTCTTT3′ |

| R 5′TGAGCCATCTTTGCCGAGTA3′ | |

| CD48 | F 5′TGGGAACTGGATTTCAAGGTCAT3′ |

| R 5′TCAGACTCGAAGATTGTCTTTGT3′ | |

| CD74 | F 5′GGCTAGAGCCATGGATGACC3′ |

| R 5′CACAGGTTTGGCAGATTTCGG3′ | |

| LGALS1 | F 5′TCAATCATGGCCTGTGGTCT3′ |

| R 5′ATGGGCATTGAAGCGAGGAT3′ | |

| COLEC12 | F 5′AGGTTTGGTATTCAGGAGGGG3′ |

| R 5′GGTGAGATGTCTCCATGCCA3′ | |

| LUM | F 5′ATCCAGAGGCTGGCGTGATT3′ |

| R 5′TCTGTGACCTTACTCTCTTGACAC3′ | |

| ANG4 | F 5′TGGCCAGCTTTGGAATCACTG3′ |

| R 5′ACAGTATCTGTCGTCCCGGCC3′ | |

| Sialyltransferase genes | |

| ST3Gal-I | F 5′GCCCACTATGCCAGACACTT3′ |

| R 5′TCAGCAGAGTCAAACCCAGC3′ | |

| ST3Gal-III | F 5′TGCTGCGGTCATGTAGGAAA3′ |

| R 5′CAGCGGAGTCAAGGGAAAGA3′ | |

| ST3Gal-IV | F 5′GGCTCTGGTCCTTGTTGTTG3′ |

| R 5′TCCCTAGAACGGTTGCCAAAA3′ | |

| ST3Gal-VI | F 5′CACCCCAAAAGCGCAGATTTATT3′ |

| R 5′CCTGCCTGAAACAGAGTCCAA3′ | |

| ST6Gal-I | F 5′TAGACGGGGACGTATCGGA3′ |

| R 5′AAAAACCATCTCAGCATCCGGC3′ | |

| ST6Gal-II | F 5′CTAGCCAGCAGGTTTTGTCCA3′ |

| R 5′AAAGAGCATTCGTTGTCGCC3′ | |

| ST6GAINAc-I | F 5′TGTTAGGGACCAGCCATCCA3′ |

| R 5′ATGAACTGGCACCTGGAATC3′ | |

| ST6GAINAc-II | F 5′CGGATGTTGTTGCTCGTTGC3′ |

| R 5′AGTCGGCTCTTTCTGTTTTCC3′ |

F, forward; R, reverse.

The primers used for Muc gene expression were designed based on sequences reported in http://www.medkem.gu.se/mucinbiology/databases/db/Mucin-mouse.htm.

Ninhydrin colorimetric assay.

Sialic acid concentration in tissue samples was determined as previously described (65). SI and colon mucus scrapes were collected from C57BL/6 and TCRδ−/− mice and immediately frozen on dry ice. Samples were diluted in water to 1 mg/ml, and 333 μl of each sample and standard was mixed with 333 μl glacial acetic acid and 333 μl acidic ninhydrin solution, vortexed, and briefly centrifuged to collect the sample at the bottom of the tube. Samples and standards were boiled for 10 min before cooling under a cold stream of water. All samples and standards were briefly centrifuged and transferred to cuvettes. The absorbance at 470 nm was immediately measured with a Hitachi spectrophotometer. Sample concentration was calculated against the sialic acid standard curve.

Alkaline borohydrate colorimetric assay.

O-glycan concentration in tissue samples was determined as previously described (10), and 100 μl of each sample and standard was mixed with 120 μl alkaline 2-cyanoacetamide reagent and boiled at 100°C for 30 min. To this 1 ml of 0.6 M borate buffer was added, vortexed, and briefly centrifuged. Each standard and sample was added to an opaque 96-well plate in triplicate and fluorescence was measured at λ = 420 nm, with an excitation of λ = 320 nm, by use of a plate reader. Sample concentration was estimated against the N-acetylgalactosamine standard curve.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses of all experimental data, except the responses of organoids to KGF, were performed by Student's t-test. The effect of the experimental conditions on the measured response in cultured organoids, i.e., crypt depth (in μm), number of crypts per organoid or number of goblet cells per crypt, was evaluated by using a nested model with fixed effects. The model comprised four factors: the experimental trial with three levels corresponding to each of the three replicated experiments; the mouse strain with two levels, WT and TCRδ−/−, the sampling time with two levels, 0 and 24 h, and the treatment, which was nested with time, with two levels, none in control cultured organoids or KGF added in stimulated organoids. The random error of the crypt depth was assumed to have a normal distribution, N(0,σ), whereas the error of both the number of crypts per organoid or number of goblet cells per crypt was assumed to have a Poisson distribution. The logarithmic transformation of the modeled quantities was required in all cases to homogenize the variance of the crypt depth and to linearize the models for the number of crypts per organoid or number of goblet cells per crypt. The effect of the experimental factors was considered significant if the P value associated to the value of the χ2 statistic was smaller than 0.05. Models were fitted by using the “genmode” procedure of the statistical package SAS 9.3.

RESULTS

TCRδ−/− mice have altered goblet cell numbers and crypt depths compared with C57BL/6 WT mice.

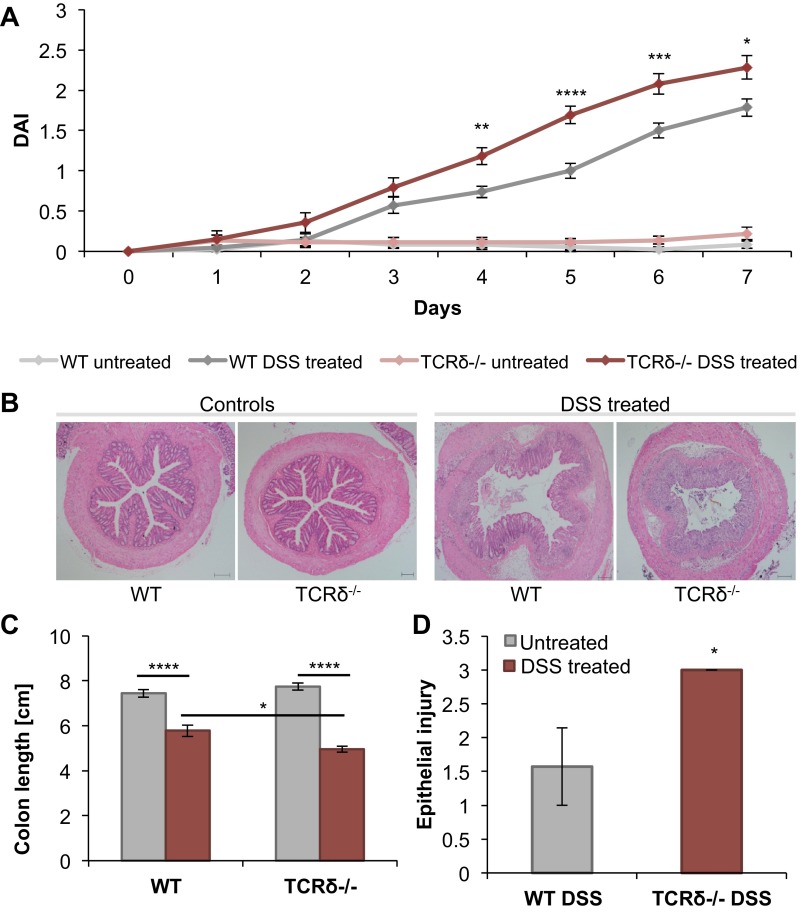

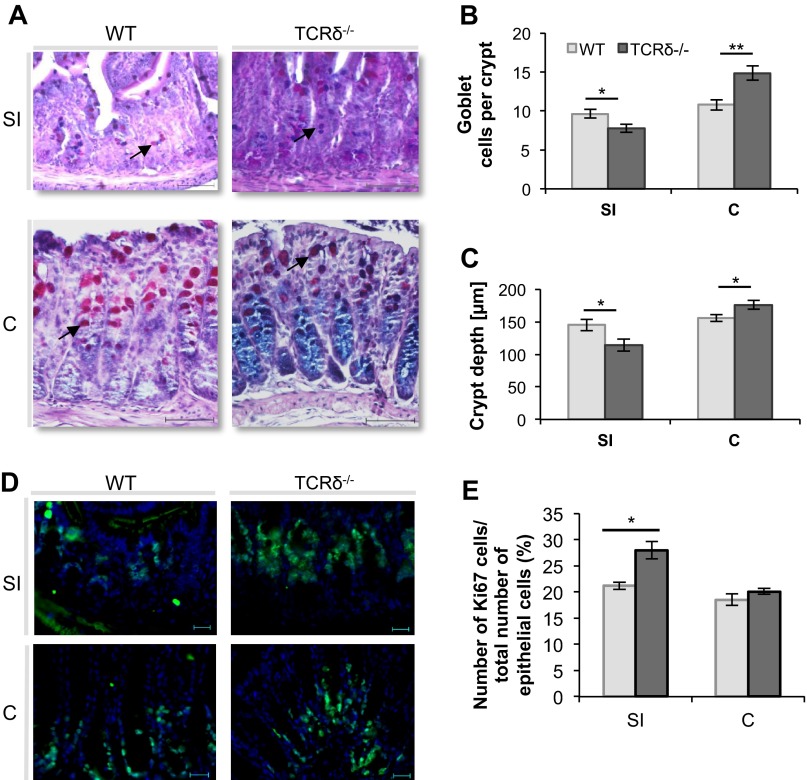

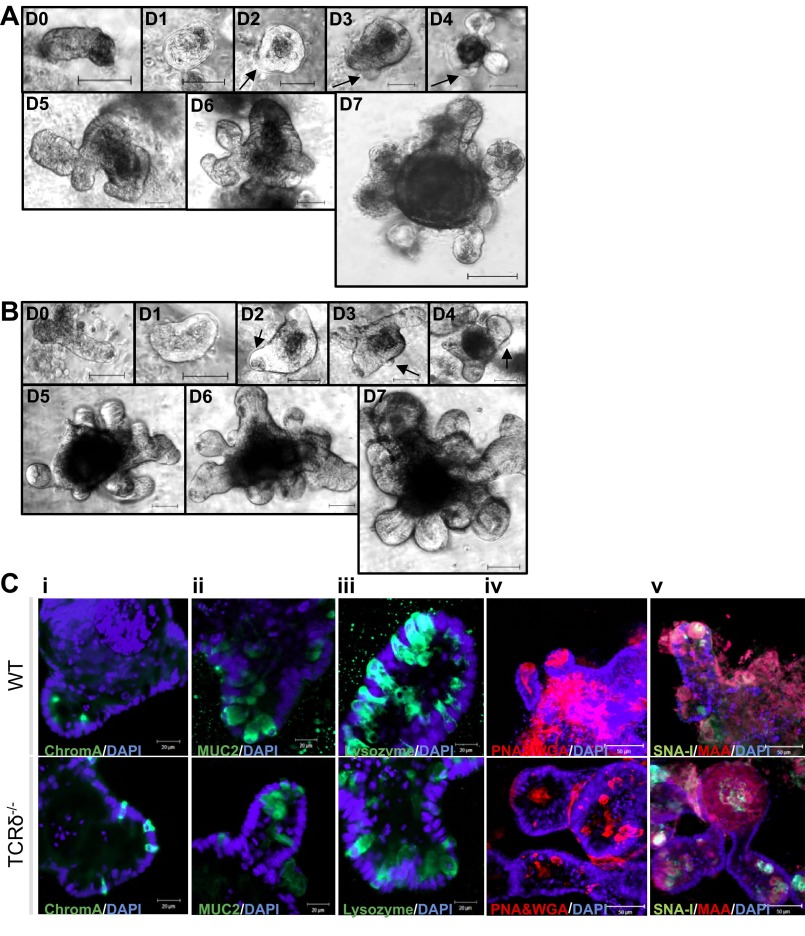

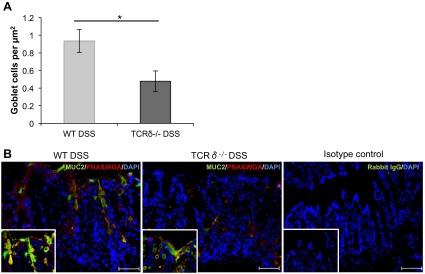

As reported earlier (6, 38), TCRδ−/− mice showed increased susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis compared with WT mice (Fig. 1). TCRδ−/− mice rapidly developed severe colitis (Fig. 1, A and B), had significantly shortened colons (Fig. 1C), and displayed increased epithelial injury in response to the 2.5% DSS treatment for 7 days (Fig. 1D), compared with WT mice. To investigate whether alterations in the mucus of TCRδ−/− mice may contribute to their increased susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis, the morphology of intestinal crypts and frequency of mucin-filled goblet cells was first determined in WT and TCRδ−/− mice by periodic acid-Schiff and Alcian blue staining (Fig. 2A). There was a marked decrease in the number of mucin-filled goblet cells per crypt in the SI (P = 0.024) of TCRδ−/− mice (Fig. 2B) whereas a significant increase was observed in the colon (P = 0.0048), compared with WT mice (Fig. 2B). The data correlate with decreased crypt depth in the SI (P = 0.036) and increased crypt depth in the colon (P = 0.044) of TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 2C). The latter is unlikely to be due to differences in cell proliferation since immunostaining with anti-Ki-67 (Fig. 2D), an antibody directed against proliferating cells, showed a significant increase in proliferating cells in the SI (P = 0.02) of TCRδ−/− mice, but similar abundance in the colon, compared with WT mice (Fig. 2E). Following 2.5% DSS treatment for 7 days, TCRδ−/− mice showed a significant reduction in mucin-filled goblet cells (P = 0.03) in the distal colon compared with WT mice (Fig. 3A). The model of acute DSS-induced colitis used in our studies did not cause inflammation in the SI in both groups of mice (histological scores of 0; data not shown). Consistent with mucin-filled goblet cell counts, Muc2 protein fluorescence staining of distal colon tissue sections was reduced in DSS-treated TCRδ−/− mice compared with DSS-treated WT mice (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 1.

TCRδ−/− mice are more susceptible to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis than wild-type (WT) mice. TCRδ−/− and WT mice (n = 13) were given 2.5% DSS in drinking water for 7 days. The disease activity index (DAI) score for all 4 groups of mice (WT untreated, WT DSS-treated, TCRδ−/− untreated, and TCRδ−/− DSS-treated) was calculated daily on the basis of stool consistency, fecal blood content, and weight loss (A). Tissue sections for all 4 groups of mice were stained with hematoxylin and eosin Y (H&E) for histological analysis (B). Colon length was measured with a millimeter ruler on the final day of the DSS study (C). The extent of epithelial injury was scored blindly from H&E-stained tissue sections of the distal colon of DSS-treated WT and TCRδ−/− mice (D). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Fig. 2.

Mucin-filled goblet cell counts and crypt depth measurements in the small intestine (SI) and colon (C) of TCRδ−/− and WT mice. SI and colon tissue of WT and TCRδ−/− mice (n = 7) was stained with periodic acid-Schiff and Alcian blue (PAS/AB) (A). Average mucin-filled goblet cell (arrow indicates mucin-filled goblet cell) number (B) and crypt depth (C) were calculated from 10 crypts per mouse tissue, for 7 mice. SI and colon tissue of WT and TCRδ−/− mice (n = 3–5) was stained with anti-Ki67 (D) and the percentage of proliferating cells was determined from this (E). Magnification, ×400; scale bars, 50 μm. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Fig. 3.

Mucin-filled goblet cell counts and Muc2 staining in the colon of WT and TCRδ−/− mice following DSS treatment. Average mucin-filled goblet cell numbers (n = 6) were calculated from tissue area measurements. *P < 0.05. Distal colon sections of DSS-treated WT and TCRδ−/− mice (n = 3) were stained with anti-MUC2 (green) and counterstained with PNA and WGA (red) and DAPI (blue). Rabbit IgG represents the isotype control. Magnification, ×200; scale bars, 100 μm; Inset magnification, ×400.

TCRδ−/− mice display an apparent intact mucus layer.

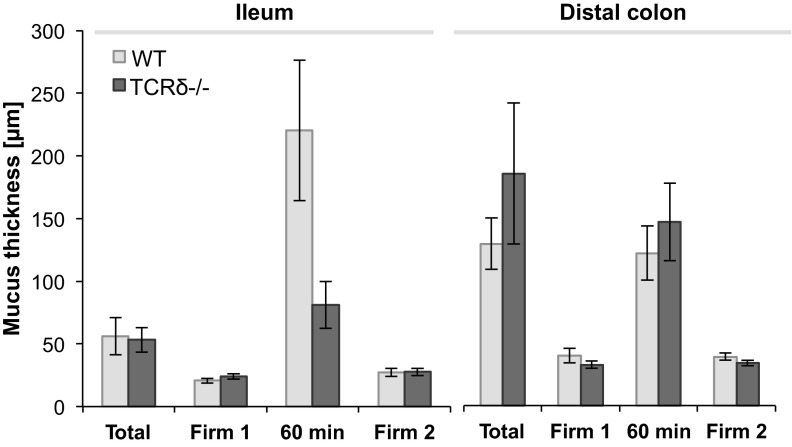

To determine whether the lack of γδ T cells and the resulting alteration in goblet cell numbers may impact on the architecture and thickness of the mucus layers of TCRδ−/− mice, mucus measurements were performed in vivo in the ileum and distal colon of WT and TCRδ−/− mice (Fig. 4). The intestinal mucus layer was visualized by the addition of charcoal to the exposed surface. The total mucus layer thickness, as measured with micropipettes, was found to be 56 ± 14 μm (n = 8) and 53 ± 9 μm (n = 7) in the ileum of WT and TCRδ−/− mice, respectively. Total mucus thickness in the distal colon of WT and TCRδ−/− mice was found to be 135 ± 21 μm (n = 6) and 194 ± 59 μm (n = 8), respectively. The loose mucus layer could be easily aspirated, showing that TCRδ−/− mice possess a distinct outer mucus layer, as shown for WT mice, leaving a thin firmly adherent ileum layer of 23 ± 2 μm and distal colon layer of 34 ± 2 μm, compared with 20 ± 1 μm and 41 ± 6 μm in WT mice, respectively. These results indicate that both firm and loose mucus layer thickness is similar in WT and TCRδ−/− mice. Regeneration of the loose mucus layer occurred over a 60-min period following removal of the loose layer, as reported earlier in the ileum and colon of rats, mice, and human explants (2, 20, 48). The thickness of the firm mucus layer was measured at the end of the regeneration process and found to be maximally 6.6 μm different to initial ileum and colon firm mucus thickness, confirming that the procedure did not impact on the integrity of the mucus architecture. These data indicate that the gross molecular organization of the mucus layer is similar in WT and TCRδ−/− mice. Similarly, no changes in the concentration of mucus-associated IgA were observed between the two groups of mice (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

In vivo mucus measurements in the ileum and distal colon of TCRδ−/− and WT mice. Mucus thickness (n = 7) was measured in vivo using a micropipette connected to a micromanipulator. Total mucus thickness (Total) indicates the thickness of the firm and loose layer. After removal of the loose layer, firm layer thickness was immediately measured (Firm 1). The mucus layer was allowed to regenerate and measured (60 min). The firm mucus layer was measured again after a second removal (Firm 2) to confirm its steady state.

TCRδ−/− mice display altered mucin expression and glycosylation.

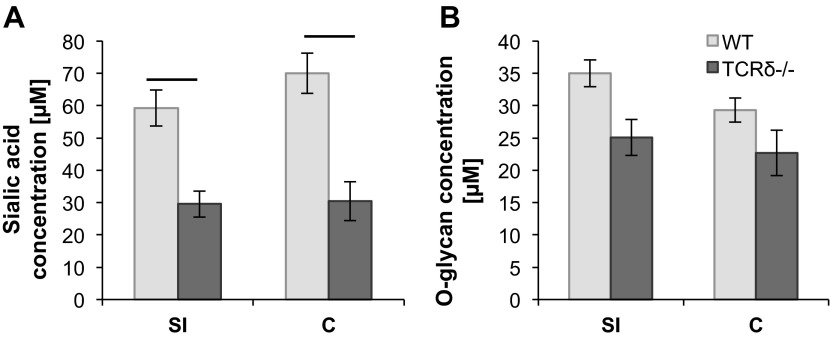

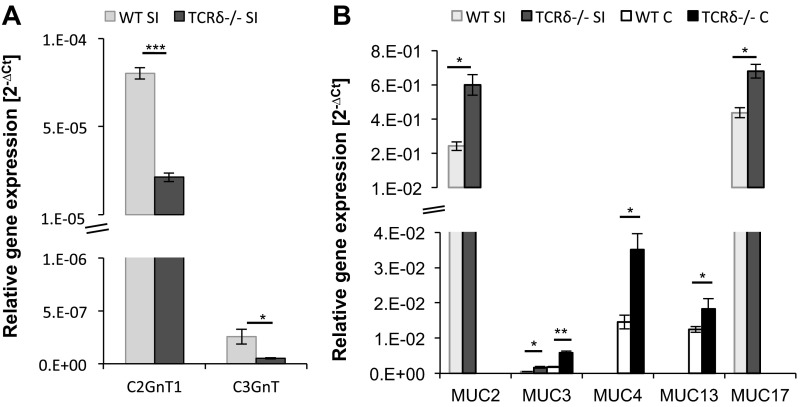

Secreted and cell-surface mucins are the main glycoproteins found in the intestinal mucus barrier. Mucins are decorated with a dense array of complex O-linked carbohydrates assembled by the sequential action of GTs. To further investigate potential variation in mucus composition in TCRδ−/− mice, O-glycan and sialic acid concentrations were determined biochemically from mucus of the SI and colon of both groups of mice. This analysis revealed that the amount of sialic acid was significantly lower in TCRδ−/− mice in both the SI (P = 0.047) and the colon (P = 0.031) (Fig. 5A), compared with WT mice, whereas no significant changes were observed in the amount of O-linked oligosaccharide chains between the two groups of mice (Fig. 5B). The O-glycan structures present in mucin consist predominantly of core 1–4 mucin-type O-glycans containing GalNAc, Gal, and GlcNAc (45). In humans, the majority of colonic mucin glycans terminated with Neu5Ac are made up of core-3 and core-4 structures (18, 24, 51), whereas murine colonic mucins are characterized by core-1 and core-2 structures with only low amounts of core-3 and core-4 type glycans (31, 61). In the human SI, the main mucin core structure is core-3, whereas in murine SI mucins core-1 and core-2 glycan structures predominate (24, 27, 60). These core structures are further elongated and frequently modified by fucose or sialic acid residues (4). Each sequential step is catalyzed by different GT isozymes (49). We analyzed expression of GT genes involved in the synthesis of the main core structures (C1GalT1, C1GalT2, C2GnT1, C2GnT2, C2GnT3, and C3GnT) and sialyltransferases (STs) involved in chain elongation (ST3Gal-I, ST3Gal-III, ST3Gal-IV, ST3Gal-VI, ST6Gal-I, ST6Gal-II, ST6GalNAc-I, and ST6GalNAc-II), by qRT-PCR. In mouse, C1GalTs, C2GnT1, C2GnT2, and C3GnT1 are expressed in the colon, whereas C1GalTs, C2GnT1, C2GnT3, and low amounts of C3GnT1 are found in the SI (58, 64, 66). Our analysis showed that core-1 C1GalT1 and C1GalT2 displayed the highest GT expression levels, albeit not significantly different between the two groups of mice (data not shown), in agreement with the increased proportion of core 1 structures (31, 61). Significant differences in gene expression between WT and TCRδ−/− mice were observed for core-2 C2GnT1 and core-3 C3GnT. In the SI tissue, C2GnT1 (P = 0.00013) and C3GnT (P = 0.045) gene expression was significantly lower in TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 6A). In the colon, GT gene expression was similar between the two groups of mice (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Sialic acid and O-glycan concentration analysis in the SI and colon of WT and TCRδ−/− mouse mucus. Sialic acid concentration was determined by ninhydrin colorimetric assay for SI and C tissue (n = 5) (A). O-glycan concentration was determined by alkaline borohydrate colorimetric assay for SI and C tissue (n = 6) (B).

Fig. 6.

Glycosyltransferase and mucin expression analysis in the SI and colon of WT and TCRδ−/− mice. Glycosyltransferase (GT) gene expression of the SI of WT and TCRδ−/− mice (n = 3) was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and is represented as relative gene expression (2−ΔCt) (A). Gene expression of Muc1, Muc2, Muc3, Muc4, Muc5AC, Muc6, Muc12, Muc13, Muc17, and Muc19 was analyzed in the SI and colon of WT and TCRδ−/− mice (n = 3) by qRT-PCR, and represented as the relative gene expression (2−ΔCt) (B). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Next, we measured the mRNA expression of the main intestinal mucins, Muc1, Muc2, Muc3, Muc4, Muc5ac, Muc6, Muc12, Muc13, Muc17, and Muc19, in the colon and SI of TCRδ−/− and WT mice. The secreted Muc2 mucin and the membrane-bound Muc13 and Muc17 mucins are the major mucins expressed in the intestine under normal physiological conditions in humans and mice (34, 38). In agreement with this, the Muc2 and Muc17 mucins were the most highly expressed in both the SI and colon of both groups of mice. There were significant differences in mRNA expression of the secreted gel-forming Muc2 and the membrane-bound Muc3, Muc4, Muc13, and Muc17 between WT and TCRδ−/− mice. In the SI, significantly higher gene expression of Muc2 (P = 0.024), Muc3 (P = 0.048), and Muc17 (P = 0.034) was observed in TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 6B). In the colon, significantly higher gene expression of Muc3 (P = 0.0043), Muc4 (P = 0.047), and Muc13 (P = 0.016) was shown in TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 6B). Taken together these findings suggest a role for γδ T cells in the regulation of mucin expression. Whether this is due to mediators of γδ T cells that directly or indirectly promotes mucin biosynthesis requires further investigation.

TCRδ−/− SI crypt organoid cultures support the role of γδ T cells in modulating the epithelium.

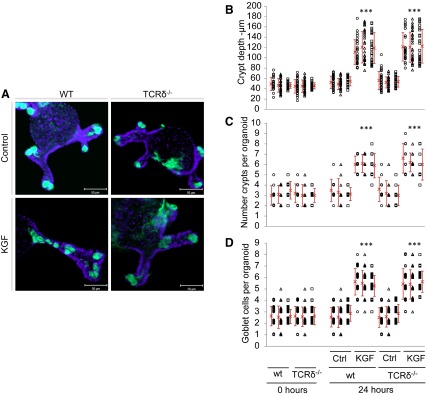

To investigate the possible mechanisms leading to reduced goblet cell numbers and altered mucin expression levels in the SI of TCRδ−/− mice, and to uncouple the potential impact of γδ T cells on intestinal crypts in WT mice, SI crypts were isolated from WT and TCRδ−/− mice and maintained in Matrigel culture for 61 days. Budding crypts and the central lumen of the organoid structures consist of a single layer of polarized epithelial cells, in agreement with previous reports (52). The growth pattern of TCRδ−/− SI crypts was similar to that of WT SI crypts (Fig. 7, A and B). SI crypts for fluorescence staining were cultured for 4 days to produce organoids composed of numerous newly formed crypts that could be characterized on the basis of differentiation and integrity markers. Similar phenotypic characteristics were observed between the two groups of mice (Fig. 7C). Enteroendocrine cells (chromogranin A staining, Fig. 7Ci) were scattered throughout the crypt. Goblet cells (MUC2 staining, Fig. 7Cii) were observed in the lower third of the crypt, whereas Paneth cells (lysozyme staining, Fig. 7Ciii) were seen along the whole length of the crypt. Lectin staining (PNA and WGA, Fig. 7Civ; SNA-I and MAA, Fig. 7Cv) confirmed expression of extended sugar chains in cultured organoid structures of both groups of mice. The frequency of goblet cells, as determined by anti-MUC2 fluorescence staining of TCRδ−/− crypt organoid cultures, was similar to the organoid cultures from WT mice. We thus hypothesized that the higher number of goblet cells observed in SI tissue of WT mice, compared with TCRδ−/− mice, required the presence of γδ T cells, which are absent in the WT organoid cultures. KGF plays a critical role in intestinal epithelial growth and maintenance (26, 33), and DSS-activated γδ T cells express KGF in the intestinal mucosa (6). KGF causes an increase in goblet cell number in the rat intestine (15, 26). Thus we investigated whether WT and TCRδ−/− SI organoids would respond to KGF in a similar manner.

Fig. 7.

TCRδ−/− SI crypts display similar growth patterns and differentiation and integrity characteristics compared with WT organoids. Images of SI crypts (n = 30–40) that form a cyst (D1) and then further develop through budding of new crypts (arrows) from the cyst body (D2–D7). A: day 0–day 7 images of C57BL/6 WT crypts. (B) day 0–day 7 images of TCRδ−/− crypts. Magnification ×200; scale bars, 50 μm. SI organoids from both groups of mice (n = 30–40) were stained with anti-chromogranin A (ChromA, Ci), anti-MUC2 (Cii), anti-lysozyme (Ciii), PNA and WGA (Civ), and SNA-I and MAA (Cv) lectins. Organoids were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Magnification ×400.

The overall analysis of the experimental conditions on the measured organoid response (Fig. 8A) showed that all responses, i.e., crypt depth (Fig. 8B), number of crypts that make up an organoid (Fig. 8C), and the number of Muc2-positive goblet cells per crypt (Fig. 8D), increased significantly (P < 0.001) in crypts cultured for 24 h with KGF added into the growth medium whereas no significant effect of the mouse strain, sampling time, or experimental trial was observed in any case. These results are consistent with the responses observed in rat tissue (15, 26), and the phenotype observed in WT tissue (Fig. 2), supporting the functional role of KGF in vivo. Furthermore, goblet cell distributions changed in response to KGF stimulation, with goblet cells being located not just in the lower third of the crypt, but distributed along the entire crypt depth. The average factor (2.2) by which the crypt depth increased when cultured with KGF (Fig. 8B) was very similar to the average factor (2.1) by which the goblet counts increased (Fig. 8D), which may suggest that the increase in the number of goblet cells may be the consequence of the increase in the overall number of cells in larger crypts, and thus KGF may be involved in crypt size development without affecting crypt structure. The rapidity (24 h) of the observed response is in accordance with the cell cycle time of the SI crypt proliferating zone being 9–13 h (50). These findings support a role of KGF-producing cells, which include γδ T cells, in modulating crypt and mucus properties, consistent with the exacerbation of the impact of DSS-treatment in the absence of the γδ T cell-signaling pathway in TCRδ−/− mice.

Fig. 8.

Treatment of WT and TCRδ−/− SI organoids with keratinocyte growth factor (KGF). MUC2-stained organoids grown in normal culture medium (control) and culture medium supplemented with KGF for 24 h. Organoids were counterstained with DAPI (blue) (A). Magnification, ×400. Crypt depth (μm) (B), number of crypts per organoid (C), and counts of goblet cells per crypt (D), measured in in vitro organoids from WT and TCRδ−/− mice at the initial experimental time and after 24 h in culture medium with and without KGF. Different symbols represent measurements obtained in each experimental condition (n ≈ 30) of the 3 biological replicated experiments. Symbols in C and D are stacked up to represent the number of organoids or crypts with that count. Red cross and vertical bars represent the average and standard deviation, respectively. ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

In accordance with previous studies (6, 38), TCRδ−/− mice were found to be more susceptible to DSS-induced colitis than WT mice. It has been shown that γδ T cells aid in the limitation of opportunistic penetration of commensal bacteria across the mucosal surface, a phenomenon seen at early time points of injury by DSS-induced colitis (29). γδ IEL activation appears to be dependent on epithelial cell-intrinsic MyD88, a key mediator of microbial-host cross talk, suggesting that epithelial cells supply microbial cues to γδ IELs (16). Given the role played by the mucus layer in limiting bacterial penetration, we hypothesized that γδ T cells may reinforce mucus barrier function, thereby decreasing the likelihood of detrimental tissue invasion.

Goblet cell depletion is a characteristic feature of many forms of infectious and noninfectious colitis, particularly UC, although it is not known whether it is a cause or consequence of inflammation (43). Depletion can occur due to decreases in goblet cell number, decreases in mucin biosynthesis, and/or increases in mucin secretion not matched by increased biosynthesis. Our results suggest that goblet cell depletion contributes to the more severe inflammation seen in mice lacking γδ T cells during colitis. Additionally, analysis of in vivo mucus thickness revealed that firm and loose mucus thickness is similar in TCRδ−/− and WT mice, despite differences in goblet cell numbers, which may suggest an alteration in the rate of mucus production or secretion. Expression analysis of the intestinal mucin and core GT genes showed major differences occurring in the SI of TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT mice. This highly altered SI phenotype, compared with the colon, could be associated with the higher abundance of IELs in the SI [1 IEL for every 10 intestinal epithelial cells (IECs)] compared with the large intestine (1 IEL for every 40 IEC) (3).

The addition of O-glycans is a posttranslational modification characteristic of secreted and membrane-bound mucins. Mucin glycosylation is characterized by common core structures, which are variously elongated and terminated, comprising the basis for structural diversity of glycans. Two of the most common mucin-type O-glycans in mouse intestinal mucins are based on the core-1 and core-2 structures (31, 61). Here C1GalT1 and C1GalT2 were most highly expressed in both groups of mice. Expression of both C2GnT1 and C3GnT was found to be downregulated in the SI of TCRδ−/− compared with WT mice. Furthermore, mucin sialylation was affected in TCRδ−/− mice. However, this change did not correlate with changes in gene expression, as expression levels of the STs were similar. The STs constitute a family of ∼20 members (22). For O-linked mucin glycans, each tissue expresses one or more of the ST3Gal I/II and the ST6GalNAc I-VI enzymes that form the NeuAcα2–3Galβ1–3 (NeuAcα2–6)GalNAcαThr/Ser sequence, the most common O-linked glycan (8). Rather than displaying a differential regulation in ST expression, the change in mucin sialylation observed in TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT mice may instead be the result of altered bacterial colonization in TCRδ−/− mice. γδ IELs of the SI have been shown to produce innate antimicrobial factors in response to resident bacterial “pathobionts” that penetrate the intestinal epithelium (29). Such a response is reduced in TCRδ−/− mice, allowing a different bacterial population to colonize the SI. Indeed gut bacteria, in particular pathogens, have evolved to utilize host sialic acids as a nutrient source (55) and a major strategy for colonization and pathogenesis of mammalian mucosal surfaces. Utilization of sialic acid by bacteria promotes bacterial survival in mucosal niche environments in several ways (41). Determining the composition of the mucosa-associated microbiota in TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT littermates will help assess the association between sialic catabolism and pathogenesis.

Numerous studies have described mucin abnormalities in IBD and cancer, in both animal models and patients. Significantly higher gene expression of gel-forming Muc2 was observed in the SI of TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT mice. Muc2 is the most abundantly expressed secretory mucin in the intestine and is stored in bulky apical granules of the goblet cells that form the characteristic goblet cell thecae (19). The mucin-containing granules can be secreted from the apical surface both constitutively and in response to a variety of stimuli. In addition, goblet cells can undergo so-called compound exocytosis, an accelerated secretory event resulting in acute release of central mucin granules (12). Since γδ T cells protect against the invasion of intestinal tissues by resident bacteria, specifically during the first few hours after a bacterial encounter (29), increased bacterial translocation in TCRδ−/− mice could trigger increased secretory activity of goblet cells, as recently reported in the case of colonic ischemia (35). A higher mucin secretion rate could explain the normal mucus layer thickness and organization in TCRδ−/− mice despite alterations in goblet cell numbers. The maintenance of an apparent intact mucus layer is consistent with previous studies reporting that the bacterial penetration in the TCRδ−/− mice did not arise from increased nonspecific barrier permeability (29). Muc13 and Muc17 mucins are the main membrane-bound mucins expressed in the intestine under normal physiological conditions (34, 38). In the colon, significantly higher levels of membrane-bound Muc3, Muc4, and Muc13 mRNA were seen in TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT mice. Muc13 has recently been shown to have a protective role in the colonic epithelium of mice with disruption or inappropriate expression of Muc13 gene predisposing to infectious and inflammatory disease and inflammation-induced cancer (57). Upregulation of Muc13 gene expression may be an epithelial protective mechanism induced by the host in the absence of γδ T cells. Our data also showed significantly higher levels of Muc17 mRNA in the SI of TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT mice. In humans, this region of the membrane-bound mucin gene cluster has been implicated in genetic susceptibility to IBD (53). Muc17 expression is lost in inflammatory and early and late neoplastic conditions in the colon (54). In light of these findings, upregulation of Muc17 observed in TCRδ−/− mice compared with WT mice may suggest a protective mechanism in the SI epithelium. The differential expression of mucin genes in the SI and colon of TCRδ−/− may contribute to their increased susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis.

The differentiation, activation, and functional specialization of IELs are controlled by interactions with other cell types and soluble factors. In particular, activated but not resting γδ T cells (5) can produce KGF, a unique feature of this T cell population (6). It has been reported that intestinal γδ T cells are activated in vivo to express KGF after DSS treatment and that intestinal epithelial cell proliferation is decreased in TCRδ−/− mice following DSS treatment (6). Here we showed that KGF treatment can increase goblet cell numbers in organoid cultures from TCRδ−/− mice, in line with previous reports showing an increase in goblet cell number and trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) protein expression in the rat intestine (15). This new evidence shows that γδ T cell-derived KGF could form a component in this protective mechanism.

γδ IELs are involved in the regulation of the mucosal microenvironment in response to intestinal disease, including IBD, celiac disease, graft-vs.-host disease, and parasite infection (14, 39). However, the precise role of γδ IELs remains controversial. Our data demonstrating that TCRδ−/− mice showed alteration in mucin expression and glycosylation, and goblet cell numbers, suggest that the lack of γδ IELs may compromise the nature of the mucosa-associated microbial community and/or the ability of the mucosa to cope with pathosymbionts, resulting in increased vulnerability to epithelial damage.

GRANTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and the Swedish Research Council (04X-08646). This research was funded by the BBSRC Institute Strategic Programme IFR/08/01: Integrated Biology of the Gastrointestinal Tract and BB/J004529/1: The Gut Health and Food Safety ISP. O. I. Kober was supported by a BBSRC Doctoral Training Grant award (BB/F016816/1) to the Institute of Food Research.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

O.I.K. and D.A. performed experiments; O.I.K. and C.P. analyzed data; O.I.K., C.P., L.H., and N.J. interpreted results of experiments; O.I.K. and C.P. prepared figures; O.I.K. and N.J. drafted manuscript; O.I.K., L.H., S.R.C., and N.J. edited and revised manuscript; S.R.C. and N.J. conception and design of research; N.J. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Richard Croft and Simon Deakin for technical help with animal work. We also thank Louise Wakenshaw and Isabelle Hautefort for help with DSS studies, and James Sington for help with the histological scoring of mouse tissue.

REFERENCES

- 1.An G, Wei B, Xia B, McDaniel JM, Ju T, Cummings RD, Braun J, Xia L. Increased susceptibility to colitis and colorectal tumors in mice lacking core 3-derived O-glycans. J Exp Med 204: 1417–1429, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atuma C, Strugala V, Allen A, Holm L. The adherent gastrointestinal mucus gel layer: thickness and physical state in vivo. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G922–G929, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beagley KW, Fujihashi K, Lagoo AS, Lagoo-Deenadaylan S, Black CA, Murray AM, Sharmanov AT, Yamamoto M, McGhee JR, Elson CO, Kiyono H. Differences in intraepithelial lymphocyte T cell subsets isolated from murine small versus large intestine. J Immunol 154: 5611–5619, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergstrom KS, Xia L. Mucin-type O-glycans and their roles in intestinal homeostasis. Glycobiology 23: 1026–1037, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boismenu R, Havran WL. Modulation of epithelial cell growth by intraepithelial gamma delta T cells. Science 266: 1253–1255, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Chou K, Fuchs E, Havran WL, Boismenu R. Protection of the intestinal mucosa by intraepithelial gamma delta T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 14338–14343, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheroutre H, Lambolez F, Mucida D. The light and dark sides of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 445–456, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comelli EM, Head SR, Gilmartin T, Whisenant T, Haslam SM, North SJ, Wong NK, Kudo T, Narimatsu H, Esko JD, Drickamer K, Dell A, Paulson JC. A focused microarray approach to functional glycomics: transcriptional regulation of the glycome. Glycobiology 16: 117–131, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper HS, Murthy SN, Shah RS, Sedergran DJ. Clinicopathologic study of dextran sodium sulfate experimental murine colitis. Lab Invest 69: 238–249, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowther RS, Wetmore RF. Fluorometric assay of O-linked glycoproteins by reaction with 2-cyanoacetamide. Anal Biochem 163: 170–174, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalton JE, Cruickshank SM, Egan CE, Mears R, Newton DJ, Andrew EM, Lawrence B, Howell G, Else KJ, Gubbels MJ, Striepen B, Smith JE, White SJ, Carding SR. Intraepithelial gammadelta+ lymphocytes maintain the integrity of intestinal epithelial tight junctions in response to infection. Gastroenterology 131: 818–829, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deplancke B, Gaskins HR. Microbial modulation of innate defense: goblet cells and the intestinal mucus layer. Am J Clin Nutr 73: 1131S–1141S, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dicksved J, Schreiber O, Willing B, Petersson J, Rang S, Phillipson M, Holm L, Roos S. Lactobacillus reuteri maintains a functional mucosal barrier during DSS treatment despite mucus layer dysfunction. PLoS One 7: e46399, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelblum KL, Shen L, Weber CR, Marchiando AM, Clay BS, Wang Y, Prinz I, Malissen B, Sperling AI, Turner JR. Dynamic migration of gammadelta intraepithelial lymphocytes requires occludin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 7097–7102, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Estivariz C, Gu LH, Gu L, Jonas CR, Wallace TM, Pascal RR, Devaney KL, Farrell CL, Jones DP, Podolsky DK, Ziegler TR. Trefoil peptide expression and goblet cell number in rat intestine: effects of KGF and fasting-refeeding. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 284: R564–R573, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frantz AL, Rogier EW, Weber CR, Shen L, Cohen DA, Fenton LA, Bruno ME, Kaetzel CS. Targeted deletion of MyD88 in intestinal epithelial cells results in compromised antibacterial immunity associated with downregulation of polymeric immunoglobulin receptor, mucin-2, and antibacterial peptides. Mucosal Immunol 5: 501–512, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu J, Wei B, Wen T, Johansson ME, Liu X, Bradford E, Thomsson KA, McGee S, Mansour L, Tong M, McDaniel JM, Sferra TJ, Turner JR, Chen H, Hansson GC, Braun J, Xia L. Loss of intestinal core 1-derived O-glycans causes spontaneous colitis in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 1657–1666, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill DJ, Clausen H, Bard F. Location, location, location: new insights into O-GalNAc protein glycosylation. Trends Cell Biol 21: 149–158, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grootjans J, Hundscheid IH, Lenaerts K, Boonen B, Renes IB, Verheyen FK, Dejong CH, von Meyenfeldt MF, Beets GL, Buurman WA. Ischaemia-induced mucus barrier loss and bacterial penetration are rapidly counteracted by increased goblet cell secretory activity in human and rat colon. Gut 62: 250–258, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustafsson JK, Ermund A, Johansson ME, Schutte A, Hansson GC, Sjovall H. An ex vivo method for studying mucus formation, properties, and thickness in human colonic biopsies and mouse small and large intestinal explants. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302: G430–G438, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansson GC. Role of mucus layers in gut infection and inflammation. Curr Opin Microbiol 15: 57–62, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harduin-Lepers A, Mollicone R, Delannoy P, Oriol R. The animal sialyltransferases and sialyltransferase-related genes: a phylogenetic approach. Glycobiology 15: 805–817, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heazlewood CK, Cook MC, Eri R, Price GR, Tauro SB, Taupin D, Thornton DJ, Png CW, Crockford TL, Cornall RJ, Adams R, Kato M, Nelms KA, Hong NA, Florin TH, Goodnow CC, McGuckin MA. Aberrant mucin assembly in mice causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and spontaneous inflammation resembling ulcerative colitis. PLoS Med 5: e54, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmen JM, Olson FJ, Karlsson H, Hansson GC. Two glycosylation alterations of mouse intestinal mucins due to infection caused by the parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Glycoconj J 19: 67–75, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol 10: 159–169, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Housley RM, Morris CF, Boyle W, Ring B, Biltz R, Tarpley JE, Aukerman SL, Devine PL, Whitehead RH, Pierce GF. Keratinocyte growth factor induces proliferation of hepatocytes and epithelial cells throughout the rat gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Invest 94: 1764–1777, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurd EA, Holmen JM, Hansson GC, Domino SE. Gastrointestinal mucins of Fut2-null mice lack terminal fucosylation without affecting colonization by Candida albicans. Glycobiology 15: 1002–1007, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inagaki-Ohara K, Chinen T, Matsuzaki G, Sasaki A, Sakamoto Y, Hiromatsu K, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Nawa Y, Yoshimura A. Mucosal T cells bearing TCRgammadelta play a protective role in intestinal inflammation. J Immunol 173: 1390–1398, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ismail AS, Behrendt CL, Hooper LV. Reciprocal interactions between commensal bacteria and gamma delta intraepithelial lymphocytes during mucosal injury. J Immunol 182: 3047–3054, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ismail AS, Severson KM, Vaishnava S, Behrendt CL, Yu X, Benjamin JL, Ruhn KA, Hou B, DeFranco AL, Yarovinsky F, Hooper LV. Gammadelta intraepithelial lymphocytes are essential mediators of host-microbial homeostasis at the intestinal mucosal surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 8743–8748, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ismail MN, Stone EL, Panico M, Lee SH, Luu Y, Ramirez K, Ho SB, Fukuda M, Marth JD, Haslam SM, Dell A. High-sensitivity O-glycomic analysis of mice deficient in core 2 β1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases. Glycobiology 21: 82–98, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Itohara S, Mombaerts P, Lafaille J, Iacomini J, Nelson A, Clarke AR, Hooper ML, Farr A, Tonegawa S. T cell receptor delta gene mutant mice: independent generation of alpha beta T cells and programmed rearrangements of gamma delta TCR genes. Cell 72: 337–348, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwakiri D, Podolsky DK. Keratinocyte growth factor promotes goblet cell differentiation through regulation of goblet cell silencer inhibitor. Gastroenterology 120: 1372–1380, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johansson ME, Ambort D, Pelaseyed T, Schutte A, Gustafsson JK, Ermund A, Subramani DB, Holmen-Larsson JM, Thomsson KA, Bergstrom JH, van der Post S, Rodriguez-Pineiro AM, Sjovall H, Backstrom M, Hansson GC. Composition and functional role of the mucus layers in the intestine. Cell Mol Life Sci 68: 3635–3641, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johansson ME, Hansson GC. The goblet cell: a key player in ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Gut 62: 188–189, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johansson ME, Phillipson M, Petersson J, Velcich A, Holm L, Hansson GC. The inner of the two Muc2 mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 15064–15069, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johansson MEV. Fast renewal of the distal colonic mucus layers by the surface goblet cells as measured by in vivo labeling of mucin glycoproteins. PLoS One 7: 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim YS, Ho SB. Intestinal goblet cells and mucins in health and disease: recent insights and progress. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 12: 319–330, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komano H, Fujiura Y, Kawaguchi M, Matsumoto S, Hashimoto Y, Obana S, Mombaerts P, Tonegawa S, Yamamoto H, Itohara S, Nanno M, Ishikawa H. Homeostatic regulation of intestinal epithelia by intraepithelial gamma delta T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 6147–6151, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koropatkin NM, Cameron EA, Martens EC. How glycan metabolism shapes the human gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol 10: 323–335, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis AL, Lewis WG. Host sialoglycans and bacterial sialidases: a mucosal perspective. Cell Microbiol 14: 1174–1182, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McAuley JL, Linden SK, Png CW, King RM, Pennington HL, Gendler SJ, Florin TH, Hill GR, Korolik V, McGuckin MA. MUC1 cell surface mucin is a critical element of the mucosal barrier to infection. J Clin Invest 117: 2313–2324, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGuckin MA, Hasnain SZ. There is a ‘uc’ in mucus, but is there mucus in UC? Gut 63: 216–217, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGuckin MA, Linden SK, Sutton P, Florin TH. Mucin dynamics and enteric pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol 9: 265–278, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moran AP, Gupta A, Joshi L. Sweet-talk: role of host glycosylation in bacterial pathogenesis of the gastrointestinal tract. Gut 60: 1412–1425, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nanno M, Kanari Y, Naito T, Inoue N, Hisamatsu T, Chinen H, Sugimoto K, Shimomura Y, Yamagishi H, Shiohara T, Ueha S, Matsushima K, Suematsu M, Mizoguchi A, Hibi T, Bhan AK, Ishikawa H. Exacerbating role of gammadelta T cells in chronic colitis of T-cell receptor alpha mutant mice. Gastroenterology 134: 481–490, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park SG, Mathur R, Long M, Hosh N, Hao L, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. T regulatory cells maintain intestinal homeostasis by suppressing gammadelta T cells. Immunity 33: 791–803, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petersson J, Schreiber O, Hansson GC, Gendler SJ, Velcich A, Lundberg JO, Roos S, Holm L, Phillipson M. Importance and regulation of the colonic mucus barrier in a mouse model of colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300: G327–G333, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petrosyan A, Ali MF, Cheng PW. Glycosyltransferase-specific Golgi-targeting mechanisms. J Biol Chem 287: 37621–37627, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Potten CS. Stem cells in gastrointestinal epithelium: numbers, characteristics and death. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 353: 821–830, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robbe C, Capon C, Coddeville B, Michalski JC. Structural diversity and specific distribution of O-glycans in normal human mucins along the intestinal tract. Biochem J 384: 307–316, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459: 262–265, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Satsangi J, Jewell DP, Bell JI. The genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 40: 572–574, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Senapati S, Ho SB, Sharma P, Das S, Chakraborty S, Kaur S, Niehans G, Batra SK. Expression of intestinal MUC17 membrane-bound mucin in inflammatory and neoplastic diseases of the colon. J Clin Pathol 63: 702–707, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Severi E, Hood DW, Thomas GH. Sialic acid utilization by bacterial pathogens. Microbiology 153: 2817–2822, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sheng YH, Hasnain SZ, Florin TH, McGuckin MA. Mucins in inflammatory bowel diseases and colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 27: 28–38, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sheng YH, Lourie R, Linden SK, Jeffery PL, Roche D, Tran TV, Png CW, Waterhouse N, Sutton P, Florin TH, McGuckin MA. The MUC13 cell-surface mucin protects against intestinal inflammation by inhibiting epithelial cell apoptosis. Gut 60: 1661–1670, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stone EL, Ismail MN, Lee SH, Luu Y, Ramirez K, Haslam SM, Ho SB, Dell A, Fukuda M, Marth JD. Glycosyltransferase function in core 2-type protein O glycosylation. Mol Cell Biol 29: 3770–3782, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stone EL, Lee SH, Ismail MN, Fukuda M. Characterization of mice with targeted deletion of the gene encoding core 2 beta 1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-2. Methods Enzymol 479: 155–172, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thomsson KA, Hinojosa-Kurtzberg M, Axelsson KA, Domino SE, Lowe JB, Gendler SJ, Hansson GC. Intestinal mucins from cystic fibrosis mice show increased fucosylation due to an induced Fucalpha1–2 glycosyltransferase. Biochem J 367: 609–616, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomsson KA, Holmen-Larsson JM, Angstrom J, Johansson ME, Xia L, Hansson GC. Detailed O-glycomics of the Muc2 mucin from colon of wild-type, core 1- and core 3-transferase-deficient mice highlights differences compared with human MUC2. Glycobiology 22: 1128–1139, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vaishnava S, Yamamoto M, Severson KM, Ruhn KA, Yu X, Koren O, Ley R, Wakeland EK, Hooper LV. The antibacterial lectin RegIIIgamma promotes the spatial segregation of microbiota and host in the intestine. Science 334: 255–258, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van der Sluis M, De Koning BA, De Bruijn AC, Velcich A, Meijerink JP, Van Goudoever JB, Buller HA, Dekker J, Van Seuningen I, Renes IB, Einerhand AW. Muc2-deficient mice spontaneously develop colitis, indicating that MUC2 is critical for colonic protection. Gastroenterology 131: 117–129, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xia L. Core 3-derived O-glycans are essential for intestinal mucus barrier function. Methods Enzymol 479: 123–141, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yao K, Ubuka T. Determination of sialic acids by acidic ninhydrin reaction. Acta Med Okayama 41: 237–241, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yeh JC, Ong E, Fukuda M. Molecular cloning and expression of a novel beta-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase that forms core 2, core 4, and I branches. J Biol Chem 274: 3215–3221, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]