Abstract

Recent studies implicate the muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase muscle RING finger-1 (MuRF1) in inhibiting pathological cardiomyocyte growth in vivo by inhibiting the transcription factor SRF. These studies led us to hypothesize that MuRF1 similarly inhibits insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I)-mediated physiological cardiomyocyte growth. We identified two lines of evidence to support this hypothesis: IGF-I stimulation of cardiac-derived cells with MuRF1 knockdown 1) exhibited an exaggerated hypertrophy and, 2) conversely, increased MuRF1 expression-abolished IGF-I-dependent cardiomyocyte growth. Enhanced hypertrophy with MuRF1 knockdown was accompanied by increases in Akt-regulated gene expression. Unexpectedly, MuRF1 inhibition of this gene expression profile was not a result of differences in p-Akt. Instead, we found that MuRF1 inhibits total protein levels of Akt, GSK-3β (downstream of Akt), and mTOR while limiting c-Jun protein expression, a mechanism recently shown to govern Akt, GSK-3β, and mTOR activities and expression. These findings establish that MuRF1 inhibits IGF-I signaling by restricting c-Jun activity, a novel mechanism recently identified in the context of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Since IGF-I regulates exercise-mediated physiological cardiac growth, we challenged MuRF1−/− and MuRF1-Tg+ mice and their wild-type sibling controls to 5 wk of voluntary wheel running. MuRF1−/− cardiac growth was increased significantly over wild-type control; conversely, the enhanced exercise-induced cardiac growth was lost in MuRF1-Tg+ animals. These studies demonstrate that MuRF1-dependent attenuation of IGF-I signaling via c-Jun is applicable in vivo and establish that further understanding of this novel mechanism may be crucial in the development of therapies targeting IGF-I signaling.

Keywords: insulin-like growth factor I, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, cardiac hypertrophy, muscle RING finger-1, Akt

muscle ring finger-1 (MuRF1) is a muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase localized to multiple regions of the cardiomyocyte, where it affects the function and stability of numerous proteins (2, 23, 27, 29, 38). MuRF1 localized to the sarcomeric M-line polyubiquitinates and directs the proteasomal degradation of a number of proteins, including troponin I, β-myosin heavy chain, and myosin-binding protein C (16, 22). Cytoplasmic MuRF1 in cardiomyocytes interacts with the transcription factor c-Jun and promotes specifically the degradation of phospho-c-Jun upon ischemia-reperfusion injury (23). MuRF1 also localizes to the perinuclear region of the cardiomyocyte, where it interacts with receptor for activated protein kinase C-1, inhibiting the translocation of protein kinase C-ϵ (PKCϵ) to focal adhesions following stimulation with G protein-coupled receptor agonists (2). In the nucleus, MuRF1 interacts with glucocorticoid modulary element-binding protein-1, a nuclear transcriptional regulator (27). Recent studies in skeletal myocytes have shown that MuRF1 also localizes to the plasma membrane beneath the neuromuscular junction in vivo, promoting nicotinic acetylcholine receptor turnover during atrophy (38), suggesting that MuRF1 may have yet-unknown functions at the cardiomyocyte plasma membrane in regulating membrane protein turnover and endocytosis.

These studies illustrate MuRF1's widespread effect on cardiomyocyte structure, gene expression, and signaling. Our laboratory has further conveyed MuRF1's key role in the myocardium by showing that MuRF1 inhibits pathological cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload in vivo (53). Mechanistically, we established that MuRF1 achieves hypertrophy attenuation by binding to and inhibiting the transcriptional factor serum response factor (SRF), an inducer of prohypertrophic gene expression (53). In addition, we have found that MuRF1 loss in the mouse heart blocks hypertrophy regression following the reversal of transaortic constriction (TAC), indicating that MuRF1 is required for induction of cardiac atrophy (55). Furthermore, increased expression of MuRF1 has been shown to inhibit growth and expression of pathological hypertrophy markers in response to phenylephrine, angiotensin II, endothelin-1, and serum in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVM) (2). Together, these studies have identified MuRF1 as a key regulator limiting cardiomyocyte growth in response to pathological stimuli.

We hypothesized that MuRF1 might also inhibit physiological cardiac hypertrophy, which is a process mediated by IGF-I signaling. Physiological cardiac hypertrophy, such as that which occurs in an athlete's heart in response to repetitive exercise, develops in response to IGF-I, a ligand synthesized and secreted by the liver in response to growth hormone that targets the cardiomyocyte (26). IGF-I binds to its tyrosine kinase receptor (IGF-IR) on the surface of cardiomyocytes, leading to the activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling cascade (4). Akt is a serine/threonine kinase central to the kinase cascade activated by IGF-I (44). Knockout of Akt inhibits cardiac hypertrophy in response to exercise (9), illustrating Akt's importance in promoting physiological hypertrophy. Conversely, acute cardiac-specific transgenic expression of Akt has been shown to induce hypertrophy without dysfunction (40). Together, these studies show that Akt expression itself, in addition to its activation through IGF-I signaling, is imperative for the development of physiological cardiac hypertrophy.

In this study, we examine the role of MuRF1 in physiological cardiomyocyte growth. We show that MuRF1 inhibits IGF-I-dependent growth in cardiomyocytes and limits the total protein expression of Akt, GSK-3β, and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). We go on to illustrate that the attenuation of IGF-I signaling by MuRF1 requires c-Jun, where c-Jun activity is necessary for enhanced IGF-I signaling, which was observed when MuRF1 was knocked down. These data show for the first time that c-Jun can be regulated in an IGF-I-dependent manner in cardiomyocytes and provide new evidence supporting the role of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling in cardiomyocyte growth and survival. Importantly, we establish that MuRF1 limits this newfound activity of c-Jun. Finally, we go on to show that MuRF1 acts to limit cardiac hypertrophy induced by voluntary wheel running exercise in the mouse, indicating that MuRF1-dependent limitation of IGF-I signaling is applicable in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, adenovirus transduction, and IGF-I treatment.

HL-1 cells, a continuously proliferating cardiomyocyte cell line derived from an atrial tumor, were maintained as published previously (7, 51). Before cells were cultured, tissue culture vessels were coated with a mixture of 0.02% gelatin (wt/vol)-0.5% fibronectin (vol/vol) for ∼30 min. HL-1 cells were trypsinized using 0.05% trypsin with EDTA, seeded on the gelatin/fibronectin-coated dishes at a dilution between 1:5 and 1:2, and allowed to adhere overnight in Claycomb medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% norepinephrine, and 1% l-glutamine. After culturing for at least 24 h, medium was changed to serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and HL-1 cells were treated with adenovirus at the multiplicity of infections (MOIs) and for the times indicated. Transient knockdown of MuRF1 was achieved using recombinant adenoviruses expressing scrambled shRNA control (Adshscrambled) or shRNA-MuRF1 (custom made by Vector Biolabs, Philadelphia, PA). shRNA sense sequence used for MuRF1 knockdown was GATCC-GCTCTGATCCTCCAGTACA-TTCAAGAGA-TGTACTGGAGGATCAGAGC-TTTTTTAGATCTA. Increased MuRF1 expression was achieved using previously described adenoviruses expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) or myc-tagged MuRF1/bicistronic GFP (22). Following adenovirus transduction, cells were treated with IGF-I (suspended in PBS), which was then added to serum-free DMEM at a final concentration of 10 nM.

Isolation and culturing of NRVM. NRVM were isolated using the Worthington Neonatal Cardiomyocyte Isolation System (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, dissected hearts were minced and digested using the provided trypsin solution overnight at 4°C. The next day, the digested tissue was oxygenated and warmed to 30°C, at which time trypsin inhibitor was added and incubated for 5 min. Cells were released using a standard plastic sterological pipette, and triturate supernatant was filtered through the cell strainer provided. The filter was then washed twice with L15 medium containing collagenase (provided), where filtrate was collected in the same tube as strained cells. Collagenase digestion was allowed to occur for 20 min at room temperature (rt), after which cells were collected by centrifugation. Cardiomyocytes were reconstituted in medium 199 (M199) supplemented with 15% FBS and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin and seeded on six-well dishes coated with 40 μg/ml fibronectin at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/well. Cells were cultured for 48 h, after which the medium was changed to M199 without serum. After 24-h starvation, increased MuRF1 expression was achieved using previously described adenoviruses expressing GFP or myc-tagged MuRF1/bicistronic GFP (22) in serum-free M199. Following adenovirus transduction, cells were treated with 10 nM IGF-I in PBS in serum-free M199.

JNK inhibitor treatment.

HL-1 cardiomyocytes were treated with the JNK inhibitor SP-600125, as described previously (23). Briefly, cardiomyocytes were transduced with adenovirus, treated with SP-600125 for 30 min, and then challenged with IGF-I. At the concentration and the times indicated, SP-600125 did not elicit any visible cell death or changes in cell density.

Fluorescence microscopy.

HL-1 cells were cultured on optically active flexible-membrane six-well culture plates (Flexcell International, Hillsborough, NC) coated with gelatin/fibronectin. Following transduction with GFP-expressing adenovirus and IGF-I stimulation, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS and membranes cut into 1 × 1 cm sections and mounted onto glass slides with medium containing DAPI. Fluorescent imaging was carried out using a Leica DMIRB inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) and a Hamamatsu (Bridgewater, NJ) Orca ER camera with a ×40 objective lens. Pixel/mm scale was set in Image J using an image of a 1-mm graticule taken with the Hamamatsu Orca ER camera under the ×40 objective lens of the Leica DMIRB inverted fluorescence microscope. Cardiomyocyte area was determined using Image J software, in which a minimum of 200 cells in replicate wells in each experimental group was measured.

RT-PCR determination of mRNA expression.

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer's protocols (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was made using the High Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). One microliter of cDNA product was then amplified on an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System in 12 μl of final volume using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix. The PCR reaction mix included 0.6 μl of mouse-specific Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems) for MuRF1 (Mm01185221_m1), ryanodine receptor 1 (RYR1; Mm01175211_m1), insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 (Igfbp5; Mm00516037_m1), and MAPK13 (Mm00442488_m1). 18S (Hs99999901_s1) was used as a reference gene. Raw threshold cycle (CT) values were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method, where CT values were first normalized to 18S and then normalized to either vehicle control (RYR1, Igfbp5, and MAPK13) or adenovirus control (MuRF1). Fold change values (calculated by the formula 2−ΔΔCT) were used as final expression data.

Antibodies and immunoblot.

Cells were lysed in the presence of 2× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), 1× phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science), and 0.2 M glycerol-2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored at −80°C. Fifteen to twenty-five micrograms of protein was resolved on either 4–12 or 10% NuPAGE gels (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), transferred to Immobilon-polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA), blocked in 2% ECL-blocking reagent (GE Healthcare Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) in 1× TBST for 30 min, and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. After washing, horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody was added to the polyvinylidene difluoride membranes for 1 h at rt. Signal was detected using ECL Prime (GE Healthcare Amersham), and final immunoblot results were acquired using hyperfilm (GE Healthcare Amersham). Densitometry analysis was performed using Quantity One 1-D Analysis Software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Antibodies recognizing Akt, phosphorylated (p)-Akt (Ser473 and Thr308; catalog nos. 9272, 9271, and 9275, 1:1,000), c-Jun, and p-c-Jun (Ser63, Ser73, and Thr91) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (catalog nos. 9165, 9261S, 9164S, and 2303S at 1:500). Antibodies recognizing GSK-3α/β and p-GSK-3β (Ser9; catalog nos. 44-610 and 44-600G; Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) were used at 1:4,000 and 1:1,000 dilutions, respectively. Anti-MuRF1 was purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN; catalog no. AF5366, 1:250 dilution), and anti-β-actin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. A5441, 1:4,000).

Animals.

MuRF1−/− mice (129S/C57BL6) and α-MHC-MuRF1 (cardiac-specific) transgenic mice (DBA/C57BL6) aged 8–16 wk were used as described (53, 56). After 5 wk of monitored wheel running exercise (or sham exercise), mice were euthanized and hearts flash-frozen and stored at −80°C or perfusion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee for animal research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Unloaded voluntary wheel running and conscious echocardiographic analysis.

Female mice were assigned to either unloaded (no resistance) wheel running or sedentary control groups, as described previously (54). Mice were randomly assigned to running or sham control groups and monitored in parallel by echocardiography on conscious mice using a Visual Sonics Vevo 770 and 2100 ultrasound biomicroscopy system at baseline, 2 wk, and 5 wk, as described previously (55, 56).

Histology and cross-sectional cardiomyocyte area analysis.

Fixed cardiac tissue was processed for paraffin embedding, sectioned, and stained with standard hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). H & E-stained slides were scanned using an Aperio Scanscope and exported using Aperio Imagescope software (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA). Paraffin-embedded cardiac sections were stained with a TRITC-labeled lectin, as described previously (53), and cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area was measured using Image J software. A minimum of 15 random fields at ×200 magnification in the left ventricle were imaged via fluorescent microscopy from at least three different hearts.

Measurement of exercise statistics.

Exercise wheel use was measured using a Mity 8 Cyclocomputer (model CC-MT400), recording running time, average speed, and distance. Running statistics were recorded daily.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR determination of mRNA expression from heart tissue.

Whole heart tissue was homogenized in RLT Plus Lysis buffer, containing β-mercaptoethanol at a 1:100 dilution, from Qiagen's RNeasy Kit. Total RNA was isolated from whole heart lysate using the RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer's protocols. cDNA was made using the High Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems). One microliter of cDNA product was then amplified on an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System in 12 μl of final volume using the TftbaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix. The PCR reaction mix included 0.6 μl of mouse-specific Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems) for either brain natriuretic peptide (BNP; Mm00435304_g1), atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP; Mm01255747_g1), smooth muscle actin (Mm00808218_g1), TATA box-binding protein (Tbp; Mm00446971_m1), or hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt; Mm01545399_m1). Raw CT values were analyzed according to the ΔCT method using multiple reference genes (Tbp and Hprt). ΔCT values for each gene were calculated by normalizing to the average CT value over all experimental groups. Reference gene correction factors for each animal were calculated by taking the geometric mean of Tbp and Hprt ΔCT values for that animal. Final expression data for each target gene were calculated by dividing the ΔCT value by the reference gene correction factor. Expression data for BNP, ANF, and smooth muscle actin were averaged over three animals per experimental group.

Statistics.

All statistical analysis was performed using Sigma Plot software (Systat Software, Chicago, IL). A two-way ANOVA test was used to determine the source of variation when data included two independent variables. For in vivo studies, the two variables were defined as genotype and exercise assignment group (sedentary or running). Differences between specific groups were determined using a multiple-comparison posttest via the Holm-Sidak method, using the all-pairwise procedure. For in vivo cardiomyocyte area experiments, n values were defined as the total number of measured cells from separate ×200 images, at least two slides per animal, where there were three animals per experimental group. A minimum of 180 cardiomyocytes in total over all three animals per experimental group were measured. Significance level for all statistical analysis was set at P < 0.05. For in vitro studies, the two variables were defined as adenovirus and treatment. Interactions between the two variables were reported when significant (P < 0.05), and the F-statistic (regression variable from the dependent variable mean/residual regression variation) and degrees of freedom (DF) were reported.

Differences between specific groups were determined using a multiple-comparison posttest via the Holm-Sidak method using the all-pairwise procedure. For experiments using JNK inhibitor pretreatment, a three-way ANOVA test was used to determine the source of variation because three independent variables (adenovirus, pretreatment, and treatment) were identified. Interactions between all three variables, as well as pairwise interactions between variables, were reported when significant.

For in vitro cardiomyocyte area experiments, n values were defined as the total number of measured cells from at least two separate slides from three independent wells, where at least 200 cardiomyocytes per treatment group in total were measured. For in vitro RT-PCR experiments, n values were defined as expression data for each gene within each treatment group from three independent experiments. For in vitro immunoblot experiments, each treatment group is represented in three lanes, with each lane from one independent experiment, and n = 1 was defined as one lane. Significance level for all statistical analysis was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

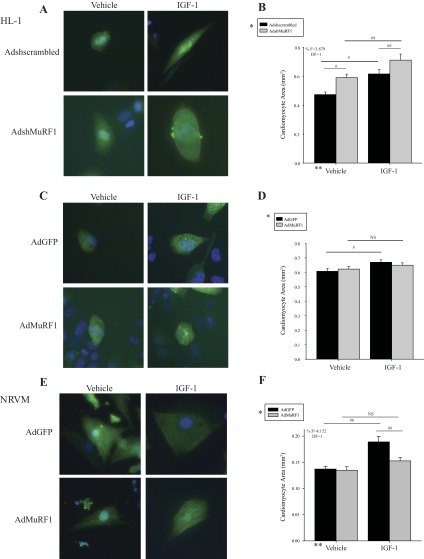

MuRF1 inhibits IGF-I-dependent cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by its effects on Akt signaling in vitro. To determine MuRF1's role in IGF-I-induced cardiomyocyte growth, HL-1 cardiomyocytes were transduced with a GFP adenovirus expressing scrambled shRNA (Adshscrambled) or shRNA specific for MuRF1 (AdshMuRF1) and challenged to IGF-I stimulation (Fig. 1A). Analysis of cellular surface area after IGF-I challenge revealed that decreasing MuRF1 (AdshMuRF1) results in an enhanced cell growth compared with vehicle-treated control cells (49.6 vs. 30.1%; Fig. 1B). In addition, there was a significant interaction between the adenovirus and treatment variables to produce these results (F = 3.879, DF = 1), providing evidence that knockdown of MuRF1 (AdshMuRF1) is required for this enhanced IGF-I-dependent growth (Fig. 1A). Conversely, increasing MuRF1 appeared to inhibit IGF-I cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (Fig. 1C). Compared with IGF-I-treated vehicle-treated cells, whose areas increased with IGF-I, IGF-I stimulation did not result in significant growth in cardiomyocytes when MuRF1 expression was increased (Ad-MuRF1; Fig. 1D). In the same manner as HL-1 cardiomyocytes, we identified that increasing MuRF1 in NRVMs also completely inhibited IGF-I-dependent cardiomyocyte growth (Fig. 1E), where statistical analysis showed that there was a significant interaction between variables (F = 4.152, DF = 1; Fig. 1F). Taken together, these studies illustrate MuRF1's inhibition of IGF-I-dependent growth in both cardiac-derived cells and primary cardiomyocytes in vitro.

Fig. 1.

Knockdown of muscle RING finger-1 (MuRF1) enhances and increased expression of MuRF1 represses IGF-I-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in HL-1 and neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVM). A: MuRF1 was knocked down using AdshMuRF1 in HL-1 cells, with Adshscrambled as control, at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 60 for 24 h in serum-free DMEM, followed by treatment with 10 nM IGF-I for 18 h. Cells were fixed and observed with a fluorescent microscope using a ×40 objective lens. Shown are representative images of vehicle- or IGF-I-treated HL-1 cardiomyocytes transduced with either Adshscrambled or AdshMuRF1. B: cardiomyocyte area (mm2) measurements of vehicle- or IGF-I-treated HL-1 cardiomyocytes transduced with either Adshscrambled or AdshMuRF1, averaged over ≥200 cardiomyocytes. C: MuRF1 was increased in expression using AdMuRF1, with AdGFP (green fluorescent protein) as a control, at a MOI of 25 for 24 h in serum-free DMEM, followed by treatment with IGF-I for 18 h. Shown are representative fluorescent images of vehicle- or IGF-I-treated HL-1 cardiomyocytes transduced with either AdGFP or AdMuRF1. D: cardiomyocyte area (mm2) measurements of vehicle- or IGF-I-treated HL-1 cardiomyocytes transduced with either AdGFP or AdMuRF1 in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRVM). E: MuRF1 was increased in expression using AdMuRF1, with AdGFP as a control, at a MOI of 25 for 24 h in serum-free medium 199 (M199), followed by treatment with IGF-I for 18 h. Shown are representative fluorescent images of vehicle- or IGF-I-treated cardiomyocytes transduced with either AdGFP or AdMuRF1. F: cardiomyocyte area (mm2) measurements of vehicle- or IGF-I-treated NRVM transduced with either AdGFP or AdMuRF1. A 2-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance. *Significance on level of adenovirus group; **significance on level of treatment group; %significant interaction between adenovirus and treatment groups. The F statistic and degrees of freedom (DF) were reported when dependence between groups was found to be a significant source of variation. Black bars, vehicle; gray bars, IGF-I-treated cells. Cardiomyocyte area measurements are represented as mean area ± SE. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.001, significance between groups as determined using a pairwise posttest.

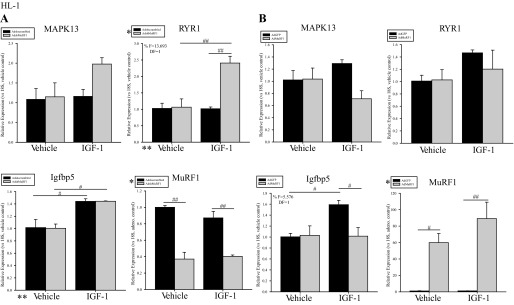

Since Akt is central in IGF-I signal transduction in vivo, we investigated MuRF1's regulation of Akt-associated regulated genes by qRT-PCR analysis. Mitogen-activated kinase 13 (MAPK13), RYR1, and Igfbp5 mRNA levels were assayed (Fig. 2) on the basis of their differential expression in transgenic cardiac Akt mice at 14 days of age (40). After 18 h of IGF-I stimulation, an approximately twofold increase in MAPK13 and RYR1 expression was seen in HL-1 when MuRF1 expression was decreased 60% using AdshMuRF1 (Fig. 2A). Specifically, statistical analysis showed that enhanced RYR1 expression required the interaction between MuRF1 knockdown (AdshMuRF1) and IGF-I treatment (F = 13.693, DF = 1) (Fig. 2A). Conversely, increased MuRF1 expression resulted in decreased MAPK13 expression (40%) and complete inhibition of IGF-I-driven RYR1 expression in HL-1 cells (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the combined effects of increased MuRF1 expression (Ad-MuRF1) and IGF-I treatment led to significantly decreased Igfbp5 expression (F = 5.576, DF = 1; Fig. 2B). Together, these data support our proposed model that MuRF1 regulates IGF-I-dependent cardiomyocyte growth in part by regulating Akt activity.

Fig. 2.

IGF-I-dependent expression of genes associated with Akt activity is inhibited by MuRF1 in HL-1 cells. A: AdshMuRF1 and control Adshscrambled were used at MOI of 60 for 24 h in serum-free DMEM to knockdown MuRF1 in HL-1 cardiomyocytes, and transduced cells were treated with 10 nM IGF-I for 18 h. RNA was isolated and cDNA generated for use in measuring expression of MuRF1, MAPK13, ryanodine receptor 1 (RYR1), IGF-binding protein 5 (Igfbp5), and 18S reference gene. Shown are RT-PCR data for each of these genes in vehicle- or IGF-I-treated HL-1 cardiomyocytes transduced with either Adshscrambled or AdshMuRF1. B: AdMuRF1 and control AdGFP were used at MOI of 25 in HL-1 cells for 24 h in serum-free DMEM to increase MuRF1, and transduced cells were treated with 10 nM IGF-I for 18 h. Shown are RT-PCR data for MuRF1, MAPK13, RYR1, Igfbp5, and 18S reference gene in cardiomyocytes transduced with either AdGFP or AdMuRF1 and treated with either vehicle or IGF-I. Raw threshold cycle (CT) values from 3 independent experiments were normalized to their respective 18S values, averaged over the experimental group, and subsequently normalized to either to vehicle control (MAPK13, RYR1, and Igfbp5) or adenovirus control (MuRF1). Final data are represented as mean fold change ± SE. A 2-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance. *Significance on level of adenovirus group; **significance on level of treatment group; %significant interaction between adenovirus and treatment groups. The F statistic and DF were reported when dependence between groups was found to be a significant source of variation. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.001, significance between groups as determined using a pairwise posttest.

MuRF1 inhibits total akt, GSK3β, and mTOR protein levels in IGF-I induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.

Like other ubiquitin ligases, MuRF1 has been shown to preferentially recognize posttranslational modification of substrates with phosphate (phosphorylation) to target the substrates by polyubiquitination, which are then rapidly degraded by the proteasome (23). This results in the rapid negative feedback of signaling that occurs commonly in biology, although the recognition of the ubiquitin proteasome system in this process is just emerging. With evidence that MuRF1 inhibits IGF-I-dependent cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and development of an Akt-specific gene expression profile, we next investigated MuRF1's regulation of IGF-I signal transduction at the protein level, given the role of ubiquitin ligases in regulating signal transduction (34).

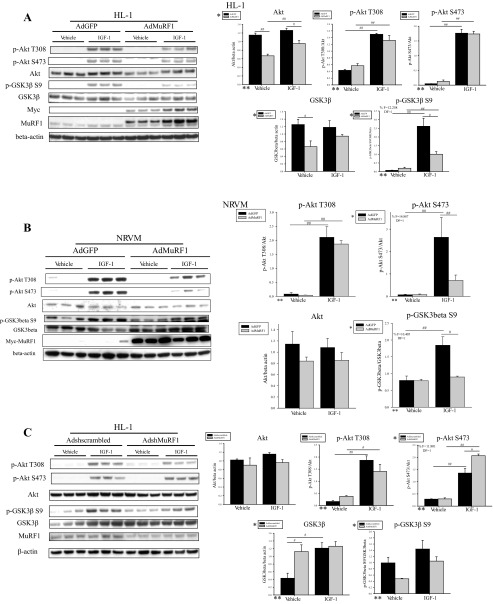

Since the fully active form of Akt is dually phosphorylated at threonine 308 (Thr308) and serine 473 (Ser473) and phosphorylates downstream effector proteins (4), we first investigated how MuRF1 regulates Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 3). We found that increasing MuRF1 resulted in a significant decrease in total Akt protein levels in vehicle- and IGF-I-treated cells but not phosphorylated Akt (Thr308 and Ser473; Fig. 3A). Phosphorylation of Akt at Thr308 was also unaffected by increased MuRF1 expression (Ad-MuRF1) in the presence of IGF-I in NRVM (Fig. 3B). Although inhibition of phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 in the presence of IGF-I was observed with increased MuRF1 expression (F = 14.887, DF = 1) in NRVM (Fig. 3B), unchanged phosphorylation of Akt at Thr308 suggests that MuRF1's primary role in inhibiting Akt activity is not via Akt's phosphorylation. Similar to the inhibition of total Akt protein expression by MuRF1, the total protein expression of GSK-3β, an immediate downstream effector of Akt (4), was decreased significantly in vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 3A). Phosphorylation (at Ser9) of GSK-3β was also inhibited, where a significant interaction between increased MuRF1 expression and IGF-I treatment was observed (F = 12.258, DF = 1; Fig. 3A), showing that signaling downstream of Akt is limited by MuRF1. Increased MuRF1 expression in NRVM was also required for inhibition of IGF-I-dependent phosphorylation of GSK-3β at Ser9 (F = 10.405, DF = 1; Fig. 3B), showing that MuRF1-dependent inhibition of Akt activity occurs in both cardiac-derived cells and primary cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 3.

MuRF1 inhibits protein expression of Akt and GSK-3β in IGF-I-stimulated HL-1 and NRVM cardiomyocytes. A: HL-1 cells were transduced with AdMuRF1 or control AdGFP at MOI of 25 for 24 h in serum-free DMEM to increase MuRF1 expression, followed by treatment with 10 nM IGF-I for 30 min. Immunoblots using whole cell lysates from 3 independent experiments are shown for p-Akt Ser473, p-Akt Thr308, Akt, GSK-3β, and p-GSK-3β Ser9. Primary antibody against myc was used to assess adenovirus-dependent expression of myc-MuRF1, and immunoblot for MuRF1 was done to determine endogenous protein levels. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of Akt, p-Akt Ser473, p-Akt Thr308, GSK-3β, and p-GSK-3β Ser9 is shown for vehicle- or IGF-I-treated cardiomyocytes transduced with either AdGFP or AdMuRF1. Total protein levels were normalized to β-actin, and phosphorylated protein levels were normalized first to β-actin and then to total protein levels. B: NRVM were transduced with AdMuRF1 or control AdGFP at MOI of 25 for 24 h in serum-free M199 to increase MuRF1 expression, followed by treatment with 10 nM IGF-I for 30 min. Immunoblots using whole cell lysates from 3 independent experiments are shown for p-Akt Ser473, p-Akt Thr308, Akt, GSK-3β, and p-GSK-3β Ser9. Primary antibody against myc was used to assess adenovirus-dependent expression of myc-MuRF1. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of Akt, p-Akt Ser473, p-Akt Thr308, and p-GSK-3β Ser9 is shown for vehicle- or IGF-I-treated cardiomyocytes transduced with either AdGFP or AdMuRF1. Total protein levels were normalized to β-actin, and phosphorylated protein levels were normalized first to β-actin and then to total protein levels. C: HL-1 cardiomyocytes were transduced with either AdshMuRF1 or control Adshscrambled at MOI of 30 for 48 h in serum-free DMEM, followed by treatment with 10 nM IGF-I for 30 min. Akt and GSK-3β expression and phosphorylation in whole cell lysates from 3 independent experiments were assessed by immunoblot using primary antibodies raised against total Akt or GSK-3β and p-Akt Ser473, p-Akt Thr308, and p-GSK-3β Ser9, as indicated. Primary antibody against MuRF1 was used to confirm knockdown. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of Akt, p-Akt Ser473, p-Akt Thr308, GSK-3β, and p-GSK-3β Ser9 is shown for vehicle- or IGF-I-treated cardiomyocytes transduced with either Adshscrambled or AdshMuRF1. Densitometry analysis is represented as means ± SE. A 2-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance. *Significance on level of adenovirus group; **significance on level of treatment group; %significant interaction between adenovirus and treatment groups. The F statistic and DF were reported when dependence between groups was found to be a significant source of variation. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.001, significance between groups as determined using a pairwise posttest.

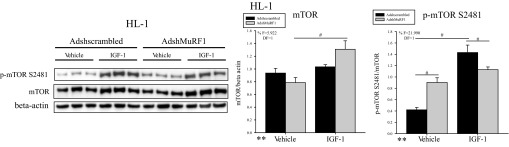

We next investigated how decreasing MuRF1 affects total and phosphorylated Akt and GSK-3β proteins in IGF-I-stimulated HL-1 cells. Surprisingly, we identified only a significant increase in p-Akt Ser473, where knockdown of MuRF1 was required for enhanced phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 in the presence of IGF-I (F = 11.801, DF = 1; Fig. 3C). p-Akt-Thr308 remained unchanged with MuRF1 knockdown in HL-1 cardiomyocytes stimulated with IGF-I (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the enhanced IGF-I-induced cardiomyocyte growth was not due to differences in the fully phosphorylated (active) form of Akt. Changes in only the Ser473-phosphorylated form of Akt in the presence of IGF-I led us to hypothesize that the total protein expression of mTOR was being altered when MuRF1 was decreased, since mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) phosphorylates Akt at Ser473 (44). Furthermore, inhibition of mTOR phosphorylation by increasing MuRF1 expression under basal conditions has been shown to occur in cardiomyocytes (5). We found that IGF-I treatment increased total protein levels of mTOR only in the presence of decreased MuRF1 (AdshMuRF1) (F = 5.922, DF = 1) (Fig. 4). Interestingly, whereas MuRF1 knockdown induced increased mTOR phosphorylation at Ser2481 in vehicle-treated cardiomyocytes, IGF-I treatment induced p-mTOR to be significantly decreased (F = 21.990, DF = 1) with the concomitant increase in total mTOR (Fig. 4). Since phosphorylated mTOR is part of the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) (44), these data suggest that MuRF1 inhibits mTORC1 basally, consistent with recently published reports (5), but that IGF-I treatment may shift MuRF1's inhibitory activity of mTOR from mTORC1 to mTORC2. Finally, immunoblot analysis of GSK-3β showed that decreasing MuRF1 expression increased total protein expression of GSK-3β in vehicle-treated cardiomyocytes, but neither GSK-3β nor p-GSK-3β Ser9 was different between AdshMuRF1 and its control after IGF-I stimulation (Fig. 3B). Together, our protein expression findings suggest that increasing MuRF1 expression may be inhibiting IGF-I growth by its effects on total Akt and GSK-3β, whereas MuRF1 knockdown releases this inhibition of IGF-I signaling by promoting total protein expression of mTOR and, by extension, mTORC2.

Fig. 4.

MuRF1 knockdown in HL-1 cardiomyocytes induces total mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) protein levels to increase upon IGF-I stimulation. HL-1 cardiomyocytes were transduced with either AdshMuRF1 or control Adshscrambled at MOI of 30 for 48 h in serum-free DMEM, followed by treatment with 10 nM IGF-I for 30 min. Total and phosphorylated (Ser2481) mTOR were measured by immunoblot of whole cell lysates from 3 independent experiments. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of mTOR and p-mTOR Ser2481 is shown for vehicle- or IGF-I-treated cardiomyocytes transduced with either Adshscrambled or AdshMuRF1. Total protein levels were normalized to β-actin, and phosphorylated protein levels were normalized first to β-actin and then to total protein levels. Densitometry analysis is represented as means ± SE. A 2-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance. **Significance on level of treatment group; %significant interaction between adenovirus and treatment groups. The F statistic and DF were reported when dependence between groups was found to be a significant source of variation. #P < 0.05, significance between groups as determined using a pairwise posttest.

MuRF1 inhibits c-Jun protein expression and phosphorylation in the presence of IGF-I. Recent studies have implicated that the sirtuin SIRT6 inhibits IGF-I/Akt signaling and the development of cardiac hypertrophy by targeting c-Jun (43). Sundaresan et al. (43) went on to show that c-Jun promotes the mRNA expression of numerous proteins involved in IGF-I signaling, including Akt, GSK-3β, and mTOR. Therefore, they demonstrated that inhibition of c-Jun by SIRT6 inhibited the expression of key components of IGF-I signaling. We also investigated the role of c-Jun in IGF-I signaling in cardiomyocytes because of our recent discovery that c-Jun is a MuRF1 substrate (23). In these previous studies, we identified that MuRF1 inhibited ischemia-reperfusion-induced cell death (apoptosis) by preventing JNK signaling. Since MuRF1 preferentially recognized phospho-c-Jun, it was able to bind activated c-Jun and direct its polyubiquitination, which then was recognized by the 26S proteasome and degraded (23). By degrading the c-Jun transcription factor, it prevented downstream signaling and apoptosis. This preferential mechanism by which phosphorylated intermediates are preferentially recognized by ubiquitin ligases and targeted for degradation by posttranslational ubiquitination is becoming more evident in biology and was a possible mechanism in IGF-I signaling through c-Jun. Therefore, we next investigated how this mechanism identified in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury may have a role in IGF-I-mediated physiological cardiac hypertrophy.

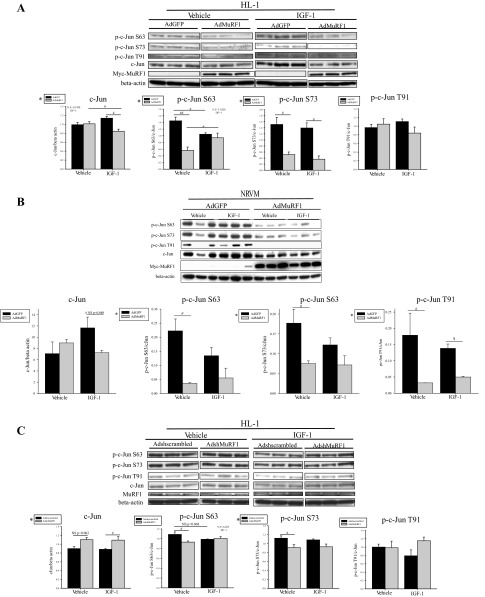

We first identified that MuRF1 inhibits IGF-I-stimulated HL-1 cells and total and phosphorylated c-Jun (p-Ser63-c-Jun and p-Ser73-c-Jun) expression levels (Fig. 5A), consistent with MuRF1's inhibition of the expression of c-Jun-mediated genes Akt, GSK-3β, and mTOR (Figs. 3 and 4) after IGF-I stimulation. Similarly, increasing MuRF1 in NRVM resulted in a decrease in phosphorylated c-Jun (Ser63, Ser73, and Thr91) in vehicle-treated cardiomyocytes and p-Thr91-c-Jun specifically in the presence of IGF-I (Fig. 5B). Conversely, when MuRF1 was decreased in HL-1 cardiomyocytes, total c-Jun expression was significantly increased in the presence of IGF-I (Fig. 5C). This is consistent with MuRF1's ability to bind c-Jun and polyubiquitinate it, which then targets it for proteasome-dependent degradation, as described recently (23). Since c-Jun is a transcription factor that drives expression of Akt, GSK-3β, and mTOR (43), our observation that Akt, GSK-3β, and mTOR total protein levels are inhibited by MuRF1 is consistent with the MuRF1-dependent limitation of c-Jun in IGF-I-stimulated cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 5.

MuRF1 inhibits cardiomyocyte c-Jun protein levels and phosphorylation in the presence of IGF-I in HL-1 and NRVM cardiomyocytes. A: MuRF1 expression was increased in HL-1 cells using AdMuRF1 and control AdGFP at MOI of 25 for 24 h in serum-free DMEM, followed by treatment with 10 nM IGF-I for 30 min. c-Jun expression and phosphorylation in whole cell lysates from 3 independent experiments were assessed by immunoblot using primary antibodies raised against total c-Jun, p-c-Jun Ser63, p-c-Jun Ser73, and p-c-Jun Thr91 as indicated. Primary antibody against myc was used to confirm adenovirus-dependent expression of myc-MuRF1. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of c-Jun, p-c-Jun Ser63, p-c-Jun Ser73, and p-c-Jun Thr91 is shown for vehicle- or IGF-I-treated cardiomyocytes transduced with either AdGFP or AdMuRF1. Total protein levels were normalized to β-actin, and phosphorylated protein levels were normalized first to β-actin and then to total protein levels. B: AdshMuRF1 and control Adshscrambled were used at MOI of 30 for 48 h in serum-free DMEM to knockdown MuRF1 in HL-1 cardiomyocytes, followed by IGF-I treatment for 30 min. Immunoblot using whole cell lysates from 3 independent experiments are shown for c-Jun, p-c-Jun Ser63, p-c-Jun Ser73, and p-c-Jun Thr91. MuRF1 primary antibody was used to confirm knockdown. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of c-Jun, p-c-Jun Ser63, p-c-Jun Ser73, and p-c-Jun Thr91 is shown for vehicle- or IGF-I-treated cardiomyocytes transduced with either Adshscrambled or AdshMuRF1. Total protein levels were normalized to β-actin, and phosphorylated protein levels were normalized first to β-actin and then to total protein levels. C: NRVM were transduced with AdMuRF1 or control AdGFP at MOI of 25 for 24 h in serum-free M199 to increase MuRF1 expression, followed by treatment with 10 nM IGF-I for 30 min. Immunoblots using whole cell lysates from 3 independent experiments are shown for c-Jun, p-c-Jun Ser63, p-c-Jun Ser73, and p-c-Jun Thr91. Primary antibody against myc was used to assess adenovirus-dependent expression of myc-MuRF1. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of c-Jun, p-c-Jun Ser63, p-c-Jun Ser73, and p-c-Jun Thr91 is shown for vehicle- or IGF-I-treated cardiomyocytes transduced with either AdGFP or AdMuRF1. Densitometry analysis is represented as means ± SE. A 2-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance. *Significance on level of adenovirus group; %significant interaction between adenovirus and treatment groups. The F statistic and DF were reported when dependence between groups was found to be a significant source of variation. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.001, significance between groups as determined using a pairwise posttest.

MuRF1-dependent regulation of IGF-I-dependent cardiomyocyte growth is JNK dependent.

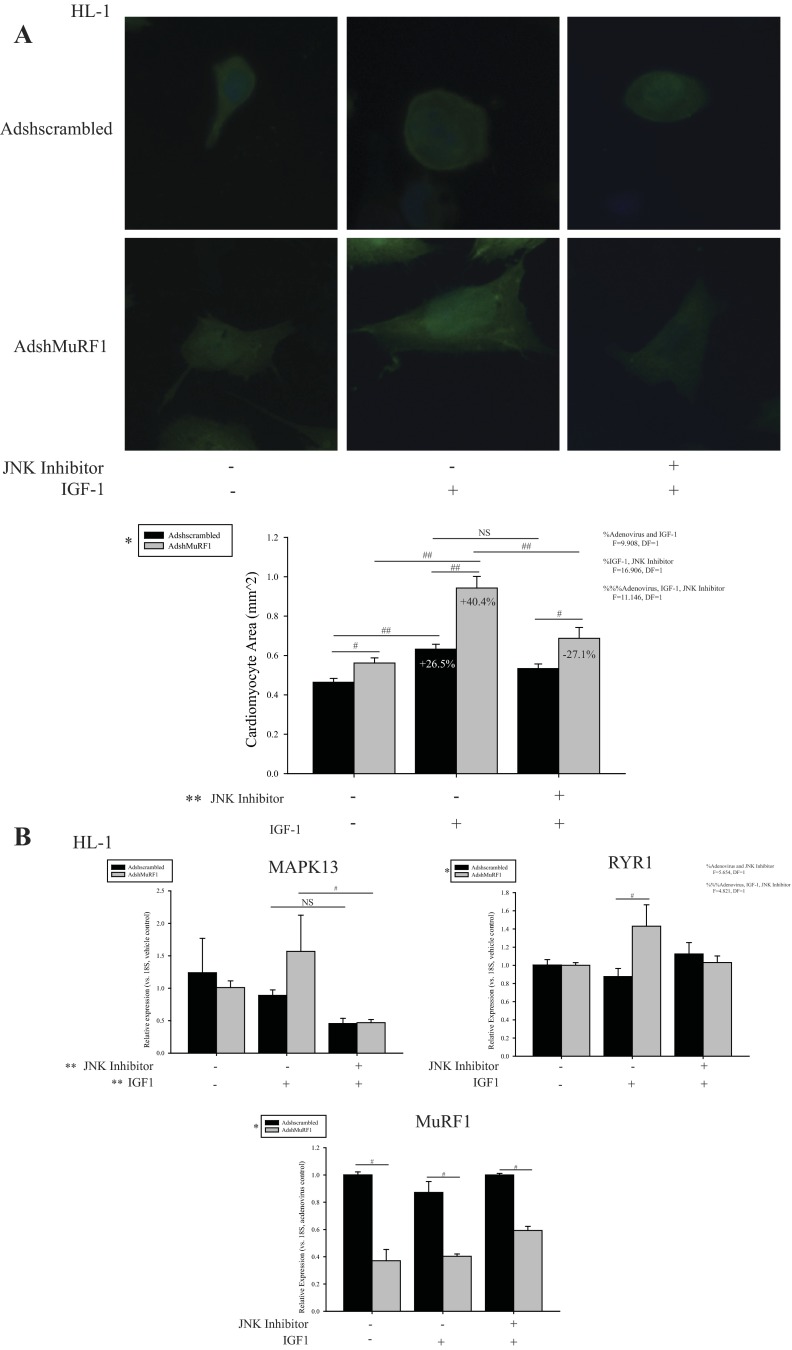

To further support our hypothesis that MuRF1 inhibits IGF-I signaling in a c-Jun-dependent manner, we next determined whether inhibiting JNK, a kinase well known to phosphorylate and activate c-Jun (30), would block MuRF1's ability to inhibit IGF-I-induced cardiomyocyte growth (Fig. 6). First, we identified that the JNK inhibitor SP-600125 was able to prevent the exaggerated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy stimulated by IGF-I that is observed when MuRF1 is transiently knocked down (Fig. 6A). Importantly, JNK inhibitor treatment acted only to limit IGF-I-dependent growth (decreasing area by 27.1%) in cardiomyocytes with decreased MuRF1 (AdshMuRF1), having no effect on the IGF-I-dependent growth on control cells (Adshscrambled) (Fig. 6A). In addition, decreased MuRF1 expression (AdshMuRF1), JNK inhibitor pretreatment, and IGF-I treatment together were required to produce these results (F = 11.146, DF = 1; Fig. 6A). Consistent with these data, MAPK13 expression was inhibited in cardiomyocytes treated with JNK inhibitor only in cells with decreased MuRF1 (AdshMuRF1; Fig. 6B). Furthermore, IGF-I-dependent enhancement of RYR1 by knockdown of MuRF1 was lost with JNK inhibition (Fig. 6B), abrogating AdshMuRF1's augmentation of RYR1 expression seen in Fig. 2. Together, these data illustrate that MuRF1's regulation of IGF-I-induced growth and Akt-specific gene expression are dependent on JNK signaling. Overall, these data illustrate a role for MuRF1 in regulating IGF-I-induced cardiac hypertrophy in part through its regulation of JNK/c-Jun activity. In the context of our previous studies indicating that MuRF1 inhibits JNK signaling by directly interacting and ubiquitinating cardiac c-Jun to target it for proteasome-dependent degradation (23), the present data illustrate a role for this mechanism in IGF-I-induced cardiac hypertrophy as well.

Fig. 6.

Exaggerated IGF-I-dependent cardiomyocyte growth and Akt-associated gene expression with MuRF1 knockdown requires JNK activity in HL-1 cells. A: MuRF1 was knocked down using AdshMuRF1, with Adshscrambled as control, in HL-1 cells at MOI of 60 for 24 h in serum-free DMEM, followed by pretreatment with 10 μM SP-600125 (JNK inhibitor) for 30 min. Cardiomyocytes were subsequently treated with 10 nM IGF-I for 18 h. Cells were fixed and observed using a fluorescent microscope with a ×40 objective lens. Shown are representative images and quantification of cardiomyocyte area (mm2) averaged over ≥200 cells/group. Cardiomyocyte area measurements are represented as mean area ± SE. B: AdshMuRF1 and control Adshscrambled were used in HL-1 cells at MOI of 60 for 24 h in serum-free DMEM to knock down MuRF1 in HL-1 cardiomyocytes. Transduced cells were pretreated with 10 μM SP-600125 (JNK inhibitor) for 30 min, followed by treatment with 10 nM IGF-I treatment for 18 h. RNA was isolated and cDNA generated for use in measuring expression of MuRF1, MAPK13, RYR1, and 18S reference gene. Raw CT values from 3 independent experiments were normalized to their respective 18S values, averaged over the experimental group, and subsequently normalized to either vehicle control (MAPK13, RYR1, and Igfbp5) or adenovirus control (MuRF1). Final data is represented as mean fold change ± SE. Shown are RT-PCR data for each of these genes in cardiomyocytes transduced with either Adshscrambled or AdshMuRF1 and treated with vehicle or both JNK inhibitor and IGF-I. A 3-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance. *Significance on level of adenovirus group; **significance on level of pretreatment group; %significant interactions between either the adenovirus, pretreatment, or treatment groups as indicated; %%%significant interaction between all 3 groups. The F statistic and DF were reported when dependence between groups was found to be a significant source of variation. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.001, significance between groups as determined using a pairwise posttest.

MuRF1 inhibits exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vivo.

Since MuRF1 inhibits IGF-I signaling in both cardiac-derived and primary cardiomyocytes in vitro, we next determined whether MuRF1 similarly inhibits IGF-I signaling in vivo. The development of physiological cardiac hypertrophy in response to regular exercise occurs through IGF-I signaling (4). So we next challenged MuRF1−/− and MuRF1 Tg+ mice and their sibling-matched wild-type controls to voluntary unloaded wheel running for 5 wk to understand the role of MuRF1-dependent inhibition of IGF-I signaling in vivo.

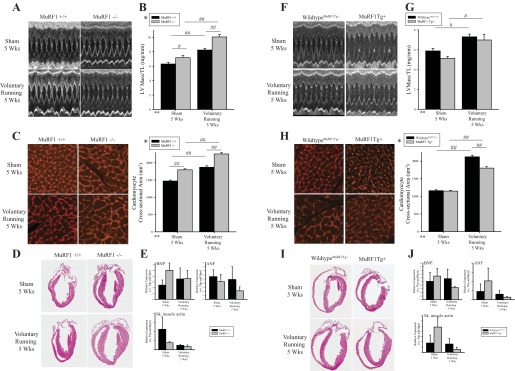

Echocardiographic analysis performed at baseline and 5 wk of voluntary running revealed that MuRF1−/− hearts exhibited significant increases in left ventricular (LV) anterior and posterior wall thickness and LV mass compared with wild-type control and sham animals (Table 1 and Fig. 7, A and B). Indicators of systolic function (EF% and FS%) did not change over the course of the experiment (Table 1). Consistent with an exaggerated cardiac hypertrophy, MuRF1−/− hearts exhibited a significant increase in LV mass/tibia length and cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area (Fig. 7, C and D). In contrast, the anterior and posterior wall thickness of MuRF1 Tg+ hearts did not increase in size significantly after 5 wk of voluntary running compared with matched wild-type control hearts by echocardiographic analysis of wall thickness (Table 2 and Fig. 7, F and G), with MuRF1 Tg+ heart cardiomyocyte cross-sectional areas exhibiting significantly less cardiomyocyte hypertrophy compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 7,H and I). These echocardiographic and histological analyses illustrate MuRF1's negative regulation of physiological hypertrophy after 5 wk of voluntary running at the level of the whole heart and cardiomyocyte.

Table 1.

Echocardiographic analysis of conscious MuRF1+/+ and sibling-matched WT control mice at baseline and 5 wk after voluntary running (or sham conditions)

| M-mode Measurement | MuRF1+/+ Baseline Sham (n = 7) | MuRF1−/− Baseline Sham (n = 10) | MuRF1+/+ Baseline Running (n = 7) | MuRF1−/− Baseline Running (n = 9) | MuRF1+/+ 5 Wk Sham (n = 8) | MuRF1 −/− 5 Wk Sham (n = 10) | MuRF1+/+ 5 Wk Running (n = 9) | MuRF1−/− 5 Wk Running (n =10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV AWTD | 1.07 ± 0.01 | 1.07 ± 0.01 | 1.04 ± 0.01 | 1.06 ± 0.01 | 1.04 ± 0.01 | 1.17 ± 0.01* | 1.29 ± 0.02* | 1.44 ± 0.04* |

| LVEDD | 2.91 ± 0.09 | 2.85 ± 0.04 | 3.13 ± 0.07 | 2.80 ± 0.14 | 3.04 ± 0.05 | 2.94 ± 0.08 | 2.95 ± 0.09 | 2.94 ± 0.06 |

| LV PWTD | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.02 | 1.01 ± 0.01 | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 1.01 ± 0.02 | 1.06 ± 0.02* | 1.20 ± 0.03* | 1.33 ± 0.02* |

| LV AWSTS | 1.73 ± 0.01 | 1.71 ± 0.03 | 1.76 ± 0.05 | 1.76 ± 0.03 | 1.72 ± 0.03 | 1.81 ± 0.02 | 1.99 ± 0.03* | 2.12 ± 0.06* |

| LVEDS | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.24 ± 0.03 | 1.40 ± 0.04 | 1.28 ± 0.08 | 1.38 ± 0.03 | 1.33 ± 0.05 | 1.36 ± 0.06 | 1.31 ± 0.04 |

| LV PWTS | 1.54 ± 0.02 | 1.52 ± 0.03 | 1.57 ± 0.01 | 1.55 ± 0.03 | 1.53 ± 0.03 | 1.54 ± 0.03 | 1.67 ± 0.03** | 1.81 ± 0.05* |

| LV Vol;d | 32.8 ± 2.6 | 31.0 ± 1.30 | 39.1 ± 2.1 | 30.4 ± 3.5 | 36.7 ± 1.5 | 33.7 ± 2.1 | 34.2 ± 2.4 | 33.6 ± 1.5 |

| LV Vol;s | 4.16 ± 0.43 | 3.76 ± 0.25 | 4.57 ± 0.01 | 4.26 ± 0.70 | 4.97 ± 0.29 | 4.55 ± 0.40 | 4.87 ± 0.56 | 4.38 ± 0.32 |

| %EF | 87.4 ± 0.5 | 87.9 ± 0.5 | 86.7 ± 0.7 | 86.3 ± 0.8 | 86.5 ± 0.6 | 86.6 ± 0.6 | 86.0 ± 0.8 | 87.1 ± 0.7 |

| %FS | 55.7 ± 0.6 | 56.4 ± 0.7 | 55.1 ± 0.86 | 54.2 ± 1.0 | 54.7 ± 0.7 | 54.7 ± 0.7 | 54.1 ± 0.9 | 55.4 ± 1.0 |

| HR | 610 ± 9 | 646 ± 10 | 641 ± 13 | 629 ± 9 | 651 ± 16 | 688 ± 6 | 663 ± 9 | 660 ± 7 |

Data are means ± SE. WT, wild type; LV AWTD, left ventricular anterior wall thickness in diastole; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LV PWTD, left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole; AWSTS, anterior wall thickness in systole; LVEDS, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; LV PWTS, left ventricular posterior wall thickness in systole; LV Vol;d, left ventricular volume in diastole; LV Vol;s, left ventricular volume in systole; %FS, %fractional shortening, calculated as (LVEDD − LVESD)/LVEDD × 100; %EF, %ejection fraction calculated as (end Simpson's diastolic volume − end Simpson's systolic volume)/end Simpson's diastolic volume × 100; HR, heart rate. Rarely, mice stopped running and were excluded from further study (preventing a repeated-measures statistical analysis). LV mass index [(ExLVD3d − LVED3d) × 1.055]. A 1-way ANOVA was performed to compare among all 8 groups.

P < 0.01 vs. all other groups;

P < 0.05 vs. all baseline.

Fig. 7.

MuRF1 regulates physiological cardiac hypertrophy induced by exercise training in MuRF1−/− and MuRF1 Tg+ mice in vivo. MuRF1−/−, MuRF1 Tg+, and sibling-matched wild-type control mice (MuRF1+/+, wild-typeMuRF1Tg+) were assigned randomly to either sedentary or running groups, where running groups were provided with an in-cage exercise wheel for 5 wk and sedentary groups were not. Cardiac growth and function were measured by echocardiography. A: representative M-mode images, containing at least 10 waveforms, from echocardiography of sedentary and running MuRF1+/+ and MuRF1−/− mice. B: left ventricular (LV) mass measurements, as measured by echocardiography, normalized to tibia length (TL) for MuRF1+/+ and MuRF1−/− mice assigned to either sedentary or running groups were also analyzed. C: perfused and fixed paraffin-embedded heart sections from sedentary and running MuRF1−/− and wild-type control mice were stained with lectin-TRITC, imaged using fluorescent microscopy to visualize cardiomyocytes, and cross-sectional area was analyzed from >180 cardiomyocytes from ≥3 animals/group. D: histological analysis of hemotoxylin and eosin was also performed. E: RNA was isolated from whole heart tissue from sedentary and running MuRF1+/+ and MuRF1−/− cDNA generated, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), atrial natriuretic peptide (ANF), smooth muscle (sm) actin, TATA box-binding protein (Tbp), and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt) expression were determined, where both Tbp and Hprt were used as reference genes. Raw CT values were normalized to the average CT value over all groups within each genotype pair to calculate ΔCT values. ΔCT values for each animal were then divided by their respective reference gene correction factor (geometric mean of Tbp and Hprt ΔCT values) to obtain final expression data for target genes (BNP, ANF, and sm actin). Three animals (n = 3) per group were used. A 2-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance. F: representative M-mode images, containing at least 10 waveforms, from echocardiography of sedentary and running MuRF1 Tg+ and wild-typeMuRF1Tg+. G: LV mass measurements, as measured by echocardiography, normalized to TL for MuRF1 Tg+ and wild-typeMuRF1Tg+ mice assigned to either sedentary or running groups were also analyzed. H: perfused and fixed paraffin-embedded heart sections from sedentary and running MuRF1 Tg+ and wild-typeMuRF1Tg+ control mice were stained with lectin-TRITC, imaged using fluorescent microscopy to visualize cardiomyocytes, and cross-sectional area was analyzed from >180 cardiomyocytes from ≥3 animals/group. I: histological analysis of hemotoxylin and eosin was also performed. J: RNA isolated from whole heart tissue from sedentary and running wild-typeMuRF1Tg+, MuRFTg+ mice cDNA was generated, and BNP, ANF, sm actin, Tbp, and Hprt expression was determined, where both Tbp and Hprt were used as reference genes (as described above). A 2-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance. *Significance on level of genotype group; **significance on level of exercise (sedentary or running) group; %significant interaction between genotype and exercise groups. The F statistic and DF were reported when dependence between groups was found to be a significant source of variation. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.001, significance between groups as determined using a pairwise posttest.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic analysis of conscious MuRF1 Tg+ and sibling-matched WT control mice at baseline and 5 wk after voluntary running (or sham conditions)

| M-Mode Measurement | MuRF1 WT Baseline Sham (n = 10) | MuRF1 Tg ± Baseline Sham (n = 10) | MuRF1 WT Baseline Running (n = 10) | MuRF1 Tg ± Baseline Running (n = 10) | MuRF1 WT 5 Wk Sham (n = 9) | MuRF1 Tg ± 5 Wk Sham (n = 10) | MuRF1 WT 5 Wk Running (n = 8) | MuRF1 Tg ± 5 Wk Running (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV AWTD | 1.04 ± 0.02 | 0.86 ± 0.02& | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 0.85 ± 0.02& | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 0.90 ± 0.02& | 1.22 ± 0.03* | 1.07 ± 0.03** |

| LVEDD | 2.51 ± 0.09* | 2.9 ± 0.10 | 2.7 ± 0.08 | 3.02 ± 0.07 | 2.73 ± 0.09 | 3.03 ± 0.05 | 2.66 ± 0.09 | 2.86 ± 0.11 |

| LV PWTD | 1.04 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.02& | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 0.81 ± 0.02& | 1.07 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 1.22 ± 0.03* | 1.02 ± 0.04** |

| LV AWSTS | 1.72 ± 0.04 | 1.46 ± 0.02 | 1.67 ± 0.04 | 1.48 ± 0.03 | 1.73 ± 0.03& | 1.51 ± 0.03* | 1.89 ± 0.04* | 1.68 ± 0.04* |

| LVEDS | 1.09 ± 0.05* | 1.68 ± 0.06&& | 1.28 ± 0.09* | 1.76 ± 0.07&& | 1.17 ± 0.05 | 1.75 ± 0.05&& | 1.23 ± 0.09 | 1.65 ± 0.11&& |

| LV PWTS | 1.56 ± 0.05 | 1.26 ± 0.02 | 1.51 ± 0.05 | 1.25 ± 0.03 | 1.63 ± 0.04 | 1.33 ± 0.02 | 1.77 ± 0.07* | 1.41 ± 0.04§ |

| LV Vol;d | 23.0 ± 1.8 | 32.9 ± 3.1&& | 28.0 ± 2.1 | 36.2 ± 2.0&& | 28.2 ± 2.3 | 36.3 ± 1.6&& | 26.5 ± 2.1 | 31.9 ± 2.8&& |

| LV Vol;s | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 8.4 ± 0.8&& | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 9.5 ± 0.9&& | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 9.3 ± 0.7&& | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 8.4 ± 1.5&& |

| %EF | 88.3 ± 0.6 | 74.3 ± 1.1&& | 84.9 ± 2.0 | 74.1 ± 1.6&& | 88.4 ± 0.5 | 74.2 ± 1.2&& | 85.6 ± 2.0 | 75.0 ± 2.2&& |

| %FS | 56.5 ± 0.6 | 41.9 ± 1.0&& | 53.1 ± 2.1 | 42.0 ± 1.4&& | 57.0 ± 0.7 | 42.2 ± 1.1&& | 53.9 ± 2.3 | 42.9 ± 1.8&& |

| HR | 704 ± 9 | 705 ± 9 | 731 ± 8 | 718 ± 14 | 750 ± 8 | 737 ± 13 | 754 ± 10 | 739 ± 7 |

Data are means ± SE. Rarely, mice stopped running and were excluded from further study (preventing a repeated-measures statistical analysis. A 1-way ANOVA was performed to compare among all 8 groups.

P < 0.01 vs. all other groups;

P < 0.05 vs. all other groups (except for MuRF1 WT baseline sham);

P < 0.01 vs. MuRF1 WT baseline groups;

P < 0.01 vs. all WT groups;

P < 0.05 vs. all other groups by MuRF1 WT baseline sham and MuRF1 Tg+ 5 wk sham. LV mass index [(ExLVD3d − LVED3d) × 1.055].

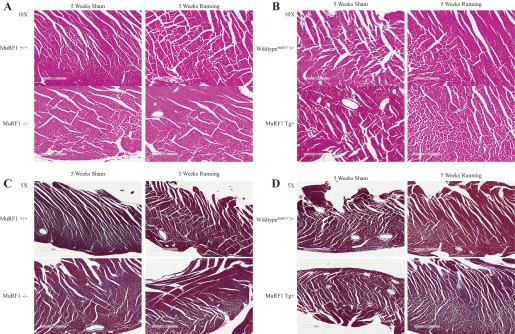

To further analyze the type of cardiac hypertrophy that the MuRF1−/− and MuRF1 Tg+ hearts were undergoing, we quantified the expression of genes upregulated in cardiac pathological hypertrophy, including brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), and smooth muscle actin, which by qRT-PCR were unchanged in cardiac tissue from MuRF1−/− running mice. Neither MuRF1−/− or MuRF1 Tg+ hearts demonstrated significant increases in gene expression after running (Fig. 7, E and J, respectively). No inflammatory or fibrotic remodeling was identified by histological analysis of MuRF1−/− or MuRF1 Tg+ heart (Fig. 8, A and B, respectively). Both the lack of pathological cardiac hypertrophy makers and the absence of any histological pathology in these studies illustrate that both MuRF1−/− and MuRF1 Tg+ hearts respond to voluntary running by undergoing physiological hypertrophy, a process driven by IGF-I-mediated cell signaling in vivo.

Fig. 8.

High-power histological analysis of MuRF−/−, MuRF1 Tg+, and sibling wild-type control hearts. A and B: hematoxylin and eosin staining of representative cardiac sections from MuRF1−/− (A) and MuRF1 Tg+ mice (B) after 5 wk of sham or running challenge. C and D: Masson's trichrome staining of representative cardiac sections from MuRF1−/− (C) and MuRF1 Tg+ mice (D) after 5 wk of sham or running challenge.

Daily analysis of the running time, average speed, and total distance was collected for each of the groups analyzed. Interestingly, both the MuRF1−/− and MuRF1 Tg+ mice ran the same amount of time as their strain-matched controls (Tables 3 and 4, respectively). Interestingly, the MuRF1−/− mice ran significantly farther than their matched control wild-type littermates for the entire 5-wk duration of the study (Table 3). Consistent with this, MuRF1−/− mice ran significantly further distances during weeks 2–5 (Table 3). In contrast, MuRF1 Tg+ mice ran the same speed and distance compared with their wild-type controls, which suggests that the MuRF1−/− mice have an enhanced cardiovascular system due to their differences in cardiac and/or muscle due to the absence of MuRF1 (Table 4). Since MuRF1 Tg+ mice were not exercise inhibited, these studies suggest that skeletal muscle MuRF1 may be responsible in part for this finding.

Table 3.

Voluntary wheel running exercise performance of MuRF1+/+ and MuRF1−/− mice

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Overall (Weeks 1–5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Running time, min/day | ||||||

| MuRF1+/+ | 329.8 ± 28.8 | 348.4 ± 18.5 | 323.0 ± 25.4 | 359.8 ± 19.3 | 341.3 ± 16.3 | 343.1 ± 14.8 |

| MuRF1−/− | 349.9 ± 28.8 | 375.5 ± 24.6 | 325.1 ± 24.3 | 384.5 ± 17.0 | 382.3 ± 31.1 | 363.7 ± 18.7 |

| Speed, mph | ||||||

| MuRF1+/+ | 2.80 ± 0.199 | 3.30 ± 0.161 | 3.31 ± 0.171 | 3.59 ± 0.146 | 3.64 ± 0.169 | 3.31 ± 0.142 |

| MuRF1−/− | 3.46 ± 0.224* | 4.84 ± 1.71 | 4.52 ± 0.303* | 4.92 ± 0.256# | 4.92 ± 0.407* | 4.47 ± 0.279* |

| Distance, km | ||||||

| MuRF1+/+ | 10.1 ± 1.2 | 12.2 ± 0.93 | 11.2 ± 0.96 | 13.9 ± 0.87 | 13.1 ± 0.91 | 12.1 ± 0.73 |

| MuRF1−/− | 13.0 ± 1.7 | 19.0 ± 2.1* | 15.6 ± 1.83* | 19.5 ± 1.32* | 19.9 ± 2.5* | 17.2 ± 1.5* |

Data are expressed as means ± SE. MuRF1+/+, n = 8–9/wk; MuRF1−/−, n = 8/wk. Rarely, mice stopped running and were excluded from further study (preventing a repeated-measures statistical analysis). Student's t-test was performed to compare MuRF1−/− with WT control animals.

P ≤ 0.05;

P < 0.001 MuRF1+/+ vs. MuRF1−/−.

Table 4.

Voluntary wheel running exercise performance of WTMuRF1 Tg+ and MuRF1Tg+ mice

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Overall (Weeks 1–5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Running time, min/day | ||||||

| WTMuRF1Tg+ | 419.4 ± 19.0 | 383.0 ± 31.2 | 332.5 ± 26.1 | 309.4 ± 38.4 | 324.4 ± 37.5 | 357.0 ± 20.0 |

| MuRF1Tg+ | 387.9 ± 35.1 | 361.9 ± 35.8 | 351.7 ± 31.7 | 342.2 ± 38.8 | 378.7 ± 51.8 | 366.2 ± 32.5 |

| Speed, mph | ||||||

| WTMuRF1Tg+ | 3.20 ± 0.179 | 4.29 ± 0.188 | 3.92 ± 0.197 | 3.83 ± 0.146 | 4.29 ± 0.216 | 3.87 ± 0.141 |

| MuRF1Tg+ | 3.38 ± 0.177 | 4.14 ± 0.281 | 4.36 ± 0.373 | 4.13 ± 0.417 | 4.50 ± 0.298 | 4.09 ± 0.286 |

| Distance, km | ||||||

| WTMuRF1Tg+ | 14.0 ± 0.82 | 17.6 ± 1.6 | 14.1 ± 1.6 | 12.5 ± 1.8 | 14.9 ± 2.3 | 14.5 ± 1.1 |

| MuRF1Tg+ | 14.0 ± 1.2 | 15.8 ± 1.1 | 15.8 ± 1.6 | 15.6 ± 2.7 | 17.2 ± 2.1 | 15.7 ± 1.4 |

Data are expressed as means ± SE. WTMuRF1Tg+, n = 6–8/wk; MuRF1Tg+, n = 7/wk. Rarely, mice stopped running and were excluded from further study (preventing a repeated-measures statistical analysis). Student's t-test was performed to compare MuRF1−/− with WT control animals. No differences between groups were identified (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Increases in cardiac workload induce the mammalian heart to grow by a process called cardiac hypertrophy that can be induced by either pathological or physiological stimulation. One pathological stimulus that commonly induces cardiac hypertrophy is sustained hypertension, which increases the heart's susceptibility to failure (19). The ability of the muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase MuRF1 to inhibit pathological cardiac hypertrophy has been published recently (2, 53). Growth of primary NRVM with angiotensin II, endothelin-1, or norepinephrine (activators of signaling pathways that drive pathological hypertrophic remodeling) has been reported to be inhibited by MuRF1 by virtue of MuRF1-dependent inhibition of PKCϵ (2). In vivo, TAC, a method used to mimic the pressure overload observed during chronic hypertension of MuRF1−/− mice, resulted in exaggerated cardiac hypertrophy (53). Furthermore, increased activity of the transcription factor SRF was observed with increased MuRF1 expression in cardiomyocytes, which showed that MuRF1 inhibition of SRF contributes to MuRF1's effect on cardiac growth following TAC (53). We have reported recently that MuRF1 and MuRF2 are functionally redundant in regulating physiological hypertrophy by regulating E2F1-mediated gene expression (57). These reports establish MuRF1's widespread inhibitory effect on pathological myocardial growth signaling on the level of both protein kinases (PKCϵ) and transcription factors (e.g., SRF). Because of this broad activity of MuRF1 in limiting these signal transduction cascades, we posited that MuRF1 would also inhibit the signal transduction cascades distinctly activated by physiological cardiac stimuli.

Cardiomyocyte growth induced by physiological stimuli such as repetitive exercise and pregnancy is beneficial because the changes in size and strength, enhanced vascular perfusion, and metabolism associated with cardiac hypertrophy occur without the adverse long-term effects seen in pathological hypertrophy (13). Physiological stimuli trigger the release of growth hormone (GH) that subsequently induces the production of IGF-I in the liver. At the molecular level, elevated circulating GH and IGF-I drive physiological cardiac hypertrophy (33). Considerable effort has been made to delineate prohypertrophic IGF-I signaling pathways in the myocardium. Circulating IGF-I is the main source of IGF-I for the cardiomyocyte. Although it has been shown that cardiomyocytes themselves transiently release IGF-I in response to exercise, this pool of IGF-I contributes to the hypertrophy effect to a much lesser extent than circulating IGF-I (3, 14, 45). At the cardiomyocyte plasma membrane, IGF-I binds to and activates the IGF-I and insulin receptor tyrosine kinases, which subsequently activate PI3Ks (26). PI3Ks catalyze the formation of PIP3, inducing phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) translocation to the plasma membrane. The crucial step in IGF-I signaling transduction is PDK1-dependent phosphorylation of Akt1, the main isoform of Akt in the heart (Akt2 is also present, but to a lesser extent) at Thr308 (28, 41). This hypophosphorylated form of Akt is fully activated by phosphorylation at Ser473 by mTORC2 (44). Akt promotes protein translation by phosphorylating and inhibiting GSK-3β, an inhibitor of the translation elongation initiation factor-2Bϵ (1, 18, 41) and phosphorylating mTOR, promoting the formation of mTORC1 and subsequent mTORC1-dependent activation of ribosome biosynthesis and protein translation (44).

In the present study, we detail for the first time the ability of MuRF1 to inhibit physiological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by acting on a novel regulator of IGF-I signaling, the transcription factor c-Jun. We show that when MuRF1's expression was knocked down, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy was enhanced, whereas increased MuRF1 inhibited cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (Fig. 1). To date, only a few endogenous molecular inhibitors of IGF-I signaling in cardiomyocytes have been described, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which acts as a phosphatase for PIP3 and Akt (8, 39), and FOXO3a, which activates transcription of genes involved in cardiac atrophy, including MuRF1 (42), indicating that inhibition of IGF-I signaling by MuRF1 in the myocardium is a novel finding. We expanded on MuRF1's role in inhibiting IGF-I-dependent hypertrophy by showing that MuRF1 inhibits Akt-associated gene expression (Fig. 2). If MuRF1 acts at the level of Akt or higher in the signaling pathway, we expected that MuRF1 would limit Akt phosphorylation; however, our findings suggested that Akt phosphorylation was not the main method by which MuRF1 inhibited Akt activity (Fig. 3) despite the observation that phosphorylation of GSK-3β, a direct target of Akt, was inhibited by MuRF1 (Fig. 3). These findings are consistent with the findings of Chen et al. (5), who demonstrated that increased MuRF1 expression in adult mouse cardiomyocytes did not alter basal levels of phosphorylated Akt. Instead, we observed that MuRF1 inhibited total Akt, GSK-3β (Fig. 3), and mTOR expression in the presence of IGF-I (Fig. 4). Interestingly, quantitative differences in MuRF1's effects on p-Akt Ser473 and p-c-Jun Thr91 were seen between NRVM and HL-1 cardiac-derived cells, reflecting possible differences in these cell systems. Since phosphorylation sites are targeted by different kinases, these minor differences may suggest differences between these cardiomyocyte model systems. Whereas NRVM are primary ventricular cells, presumed to more accurately reflect cell signaling changes in cardiac hypertrophy, HL-1 cells are derived from a cardiac atrial myxoma (CV50) tumor and are therefore of atrial origin and are immortalized cancer cells despite their mature contractile phenotype (7, 51). In addition, IGF-I-dependent MuRF1 regulation of mTOR suggested that IGF-I switches MuRF1-dependent inhibition from mTORC1 to mTORC2 (Fig. 4). Together, MuRF1's regulation of three independent proteins involved in the IGF-I pathway indicated that MuRF1-dependent inhibition of IGF-I-dependent hypertrophy and signaling was independent of Akt activation and likely involved transcriptional regulation.

There are a growing number of examples of ubiquitin ligases that regulate signal transduction by recognizing phosphorylated (activated) downstream substrates (for further details, see the recent review in Ref. 34). In the JNK signaling pathway alone, at least six proteins with ubiquitin ligase activity have been described, including MEKK1, Fbw7, DCX, itch, MuRF1, and atrogin-1/MAFbx (17, 23, 25, 31, 50, 58, 59). Interestingly, MEKK1 is a MAPK3K in the JNK signaling pathways that phosphorylates MAP2K, which in turn phosphorylates JNK, which then phosphorylates c-Jun (37). MEKK1 then acts as the ubiquitin ligase that preferentially polyubiquitinates phospho-c-Jun to target its degradation (25, 58). This novel mechanism of inhibiting signaling is not surprising, given the need for signaling to be inhibited quickly. Posttranslational modification is one of the few systems with the agility to act on this fact, and the ubiquitin proteasome system is one of few (possibly only) posttranslational modification systems that can then degrade its substrate to inhibit further signaling. In multiple cell types, inhibition of apoptosis mediated by JNK signaling is inhibited by ubiquitin ligases such as MEKK1 (NIH3T3 cells), FBw7 (neurons), DCXhDET1-hCOP1 (U2Os, HEK293T), and itch (T cells) (10–12, 15, 32, 49, 52). Although the mechanism described here is novel for the heart and IGF-I signaling, it is likely that it occurs more commonly than has been reported, given the growing number of cell types and disease processes it is being identified in.

Since a recently published study identified Akt1, GSK-3β, and mTOR in a number of cardiac genes, the promoter regions of which are bound and activated by c-Jun (43), we hypothesized that MuRF1 achieves its limitation of Akt, GSK-3β, and mTOR protein levels by inhibiting c-Jun in the presence of IGF-I. We were especially interested in c-Jun-dependent regulation of IGF-I signaling since our laboratory recently identified MuRF1's ability to inhibit JNK signaling through MuRF1's direct interaction with and degradation of c-Jun (23). In that study, we showed that in the context of ischemia-reperfusion injury, increased c-Jun degradation (by MuRF1) resulted in the inhibition of ischemia-reperfusion-induced cell death and cardiomyocyte dysfunction (23). In the present study, we found that increasing MuRF1 expression decreased total c-Jun levels when cardiomyocytes were stimulated with IGF-I; in parallel, MuRF1 reduced the amount of phosphorylated c-Jun that was present (Ser73 and Thr91) (Fig. 5). Conversely, we found that total c-Jun protein levels were increased in the presence of IGF-I when MuRF1 was knocked down (Fig. 5). Using a c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor, we then demonstrated that JNK (an activator of c-Jun) activity is required for the exaggerated IGF-I-mediated cardiomyocyte growth and Akt-associated gene expression observed when MuRF1 is knocked down (Fig. 6). Taken together, these studies suggest that MuRF1 limits IGF-I cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and signaling in part by its inhibition of JNK signaling. This mechanism is likely through MuRF1-dependent proteasome degradation of c-Jun, newly identified as a transcription factor responsible for transcription of multiple genes in the myocardium involved in the IGF-I pathway (43). c-Jun's importance in MuRF1-dependent regulation of IGF-I hypertrophy is not altogether surprising since IGF-I-induced JNK activation has been reported previously in cardiomyocytes (47) and in the maintenance of cardiac hypertrophy (20). An additional direct role of JNK signaling during physiological hypertrophy has come from recent studies describing cardiac-specific ASK1−/− mice, a MAPKKK that activates JNK and p38 (46). In response to swimming, ASK1−/− demonstrated enhanced cardiac hypertrophy, which was not affected by p38 inhibition (46), thus implicating JNK signaling as a primary mediator of physiological cardiac hypertrophy.

Exercise training induces the release of IGF-I from the liver, leading to activation of IGF-I signaling in the myocardium and cardiac growth, with limited adverse effects on cardiac function (48). In an effort to understand MuRF1-dependent regulation of endogenous IGF-I signaling in the myocardium in vivo, we submitted MuRF1−/− and MuRF1Tg+ and their littermate controls (MuRF1+/+ and wild-typeMuRF1Tg+, respectively) to voluntary wheel running exercise to increase circulating IGF-I in these animals by natural means. We discovered that loss of MuRF1 (MuRF1−/−) caused exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy to be exaggerated without pathological remodeling being provoked (Fig. 7). Conversely, exaggerated cardiac growth in response to exercise was lost in MuRF1Tg+ animals and blunted on the level of cardiomyocyte-specific growth (Fig. 7). These data confirm that MuRF1-dependent regulation of IGF-I signaling is applicable in whole animal models and provide additional evidence for the importance of the ubiquitin proteasome system in the heart. The role of ubiquitin ligases in the regulation of IGF-I signaling in the myocardium in vivo is the latest in the growing literature implicating the ubiquitin proteasome system in maintenance of cardiac function (34, 36). Mice lacking the ubiquitin ligase and protein chaperone carboxyl terminus of heat shock protein 70-interacting protein (CHIP) exhibit an exaggerated cardiac hypertrophy in as little as 1 wk and as much as 5 wk of running, which parallels increases in increased phosphorylated Akt after IGF-I stimulation in vitro (54). Although these studies suggest an inhibitory role of CHIP in Akt activation, Akt was not found to be a direct CHIP substrate, which has yet to be identified. The ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 has recently been found to regulate physiological cardiac hypertrophy induced by both IGF-I/GH injections and wheel running exercise by ubiquitination-dependent coactivation of Forkhead proteins (24). Interestingly, another recent study identified that aging MuRF1-knockout mice exhibit a spontaneous cardiac hypertrophy, lacking observable pathological remodeling after 6 mo of age, paralleling increases in phosphorylated Akt (21). The mechanism underlying these spontaneous changes in the MuRF1-knockout mouse hearts remains largely unknown, but the mechanistic relationship between MuRF1 and Akt activation was implicated in that model. Although in contrast we found that increased phosphorylated Akt was not evident over the transient knockdown periods used in the current study, we observed increases in cardiac size in MuRF1−/− compared with MuRF1+/+ mice in our sedentary controls (Fig. 7) and incremental, spontaneous increases in cardiomyocyte size with transient MuRF1 knockdown in vitro (Fig. 1), the latter of which indicating how closely the cultured cells in this study parallel in vivo findings. Regulation of cardiac growth by MuRF1 has recently been identified to contribute to cardiac disease in humans. Patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy were found to have three MuRF1 variants, including two missense and one deletion, which produce MuRF1 protein with impaired sarcomeric localization and ability to autoubiquitinate and ubiquitinate multiple substrates (5). Mechanistic studies showed that mTOR signaling is altered specifically in cardiomyocytes expressing these MuRF1 variants (5), confirming that the effect we observed in IGF-I-dependent regulation of mTOR signaling by MuRF1 in this study is relevant in human disease. Taken together, these emerging studies implicate the ubiquitin proteasome system and ubiquitin ligases, such as MuRF1 especially, as critical regulators of IGF-I signaling, with additional components likely to be found. Our current study, as well as recently published reports, illustrate the importance of studying the mechanisms by which ubiquitin ligases limit prohypertrophic signaling in the heart, especially for development of therapies for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and heart failure.

GRANTS

This study was supported by grants from the American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic Affiliate (12PRE11480009 to K. M. Wadosky), the University of North Carolina Royster Society of Fellows (UNC William R. Kenan, Jr. Fellowship to J. E. Rodríguez), the PreDoctoral Training Program in Integrative Vascular Biology (T32-HL069768 to to J. E. Rodríguez), the Jefferson-Pilot Fellowship in Academic Medicine (to M. S. Willis), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01-HL-104129 to M. S. Willis), and a Fondation Leducq Grant (to M. S. Willis).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interests, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.M.W., J.E.R., R.L.H., J.-N.M., and M.S.W. performed the experiments; K.M.W., J.E.R., R.L.H., J.-N.M., B.W., and M.S.W. analyzed the data; K.M.W., J.E.R., R.L.H., J.-N.M., B.W., and M.S.W. interpreted the results of the experiments; K.M.W., J.E.R., B.W., and M.S.W. prepared the figures; K.M.W., J.-N.M., and M.S.W. drafted the manuscript; K.M.W., J.E.R., J.-N.M., B.W., and M.S.W. edited and revised the manuscript; K.M.W., J.E.R., R.L.H., J.-N.M., B.W., and M.S.W. approved the final version of the manuscript; J.E.R. and M.S.W. contributed to the conception and design of the research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. William Claycomb for gifting the HL-1 cells used in this study and for guidance in detailing their care and use. We also thank Michael Chua and Dr. Neal Kramarcy of the Michael Hooker Microscopy Facility at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for their advice and expertise in obtaining fluorescent cell images and Sarah Edwards for editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antos CL, McKinsey TA, Frey N, Kutschke W, McAnally J, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Hill JA, Olson EN. Activated glycogen synthase-3 beta suppresses cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 907–912, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arya R, Kedar V, Hwang JR, McDonough H, Li HH, Taylor J, Patterson C. Muscle ring finger protein-1 inhibits PKC{epsilon} activation and prevents cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Cell Biol 167: 1147–1159, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker J, Liu JP, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Role of insulin-like growth factors in embryonic and postnatal growth. Cell 75: 73–82, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernardo BC, Weeks KL, Pretorius L, McMullen JR. Molecular distinction between physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy: experimental findings and therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol Ther 128: 191–227, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen SN, Czernuszewicz G, Tan Y, Lombardi R, Jin J, Willerson JT, Marian AJ. Human molecular genetic and functional studies identify TRIM63, encoding Muscle RING Finger Protein 1, as a novel gene for human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 111: 907–919, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claycomb WC, Lanson NA, Jr, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Izzo NJ., Jr HL-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2979–2984, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crackower MA, Oudit GY, Kozieradzki I, Sarao R, Sun H, Sasaki T, Hirsch E, Suzuki A, Shioi T, Irie-Sasaki J, Sah R, Cheng HY, Rybin VO, Lembo G, Fratta L, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Benovic JL, Kahn CR, Izumo S, Steinberg SF, Wymann MP, Backx PH, Penninger JM. Regulation of myocardial contractility and cell size by distinct PI3K-PTEN signaling pathways. Cell 110: 737–749, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeBosch B, Treskov I, Lupu TS, Weinheimer C, Kovacs A, Courtois M, Muslin AJ. Akt1 is required for physiological cardiac growth. Circulation 113: 2097–2104, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickens M, Rogers JS, Cavanagh J, Raitano A, Xia Z, Halpern JR, Greenberg ME, Sawyers CL, Davis RJ. A cytoplasmic inhibitor of the JNK signal transduction pathway. Science 277: 693–696, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong C, Yang DD, Tournier C, Whitmarsh AJ, Xu J, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. JNK is required for effector T-cell function but not for T-cell activation. Nature 405: 91–94, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong C, Yang DD, Wysk M, Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. Defective T cell differentiation in the absence of Jnk1. Science 282: 2092–2095, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorn GW., 2nd The fuzzy logic of physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension 49: 962–970, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Efstratiadis A. Genetics of mouse growth. Int J Dev Biol 42: 955–976, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang D, Elly C, Gao B, Fang N, Altman Y, Joazeiro C, Hunter T, Copeland N, Jenkins N, Liu YC. Dysregulation of T lymphocyte function in itchy mice: a role for Itch in TH2 differentiation. Nat Immunol 3: 281–287, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fielitz J, Kim MS, Shelton JM, Latif S, Spencer JA, Glass DJ, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Myosin accumulation and striated muscle myopathy result from the loss of muscle RING finger 1 and 3. J Clin Invest 117: 2486–2495, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao M, Labuda T, Xia Y, Gallagher E, Fang D, Liu YC, Karin M. Jun turnover is controlled through JNK-dependent phosphorylation of the E3 ligase Itch. Science 306: 271–275, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]