Abstract

The purpose of this study was to describe a novel approach to calculating service use costs across multiple domains of service for homeless populations. A randomly-selected sample of homeless persons was interviewed in St. Louis, MO and followed for two years. Service- and cost-related data were collected from homeless individuals and from the agencies serving them. Detailed interviews of study participants and of agency personnel in specific domains of service (medical, psychiatric, substance abuse, homeless maintenance, homeless amelioration services) were conducted using a standardized approach. Service utilization data were obtained from agency records. Standardized service-related costs were derived and aggregated across multiple domains from agency-reported data. Housing status was not found to be significantly associated with costs. Although labor intensive, this approach to cost estimation allows costs to be accurately compared across domains. These methods could potentially be applied to other populations.

Keywords: Homeless, service use, cost, psychiatric disorders, alcohol use disorders, drug use disorders, longitudinal

Introduction

Homeless populations have broad and complex needs and thus require a wide range of services. Homeless populations utilize a variety of services that generate cost, including housing programs, psychiatric and substance abuse treatment, case management, medical care, and incarceration. Estimated treatment and other service use costs for homeless populations have ranged from as low as $7,000 to as high as $50,000 per person annually (Gilmer, Stefancic, Ettner, Manning, & Tsemberis, 2010; Basu, Kee, Buchanan, & Sadowski, 2012; Larimer et al., 2009). Compared to the general population, homeless individuals have more frequent, lengthy, and costly medical and psychiatric hospitalizations (Salit, Kuhn, Hartz, Vu, & Mosso, 1998; Martell, et al., 1992; Hwang, Weaver, Aubry, & Hoch, 2011). Although requiring a large range of services with complex needs, homeless populations are largely uninsured and rely excessively on costly acute care services (Fleischman, 1992; O’Connell, 1999; Hwang et al., 2011; Kushel, Vittinghoff, & Haas, 2001; Kushel, Perry, Bangsberg, Clark, & Moss, 2002; Pearson, Bruggman, & Haukoos, 2007; Baggett, O’Connell, Singer, & Rigotti, 2010). Accurate cost estimates are needed to fully develop strategies for efficient delivery of services to homeless populations.

Inconsistent research methods and imprecise cost estimation approaches have likely contributed to the wide range of service cost estimates provided for homeless populations. Much of the literature studies subgroups, such as those with serious mental illness, substance use disorders, or HIV (Basu, et al., 2012). Studies assessing costs in the context of an experimental study (Jones, et al., 2003) are unlikely to coincide with costs in a natural setting. Selective inclusion of services in cost estimation promotes further variation in cost estimates. The majority of existing cost studies have based their estimates on billing and administrative systems (Larimer, et al., 2009; Gilmer, et al., 2010; Poulin, Maguire, Metraux, & Culhane, 2010; Basu, et al., 2012). The degree to which billing or administrative data sources reflect actual resource use depends on the idiosyncrasies of the system from which the data are drawn, and resulting estimates may not be comparable across systems.

The study that estimates costs for the most comprehensive range services is perhaps by Poulin and colleagues in Philadelphia (Poulin, et al., 2010). The authors estimated costs of services to a chronically homeless population in an observational study rather than as part of an intervention study. Unit costs for service types were estimated based on average costs from citywide databases. A limitation of that study is that it omits the costs of medical services, which are relatively high in homeless populations (Kushel, et al., 2002; Kuno, Rothbard, Averyt, & Culhane, 2000; Salit, et al., 1998; Culhane, Metraux, & Hadley, 2002; Culhane, Gross, Parker, Poppe, & Sykes, 2008; Rosenheck, 2000; Martinez & Burt 2006; Larimer, et al., 2009). Although deriving unit costs at a city level represents a substantial improvement over previous research designs, these estimates did not account for variation across different agencies providing the same services. That study also did not include individuals who did not use services, because the sample was developed from service databases.

The primary aim of this article is to describe a method for deriving service cost data across multiple domains of care for homeless populations and present findings for a sample of homeless individuals in St. Louis, Missouri. A naturalistic, longitudinal population-based study of a homeless sample estimated economic service costs using a agency-level perspective by combining data on self report of service use, unit costs for services, and service utilization estimates from agency records.

Materials and Methods

Sample

Currently homeless individuals were recruited for this study. Current homelessness was defined as having no current fixed address and having spent the previous 14 nights without a place of one’s own, such as in a public shelter or in some other unsheltered location or on the streets. Those who had spent the last 14 days in inexpensive transient lodging (e.g., “flophouses”) were included if they had been there for more than 30 days. Individuals who had stayed in a public shelter or unsheltered location during the last 14 days were also included but only if they had stayed less than half of those days temporarily with friends or relatives or in temporary single-room-occupancy facilities (North, et al., 2004). This project was approved in advance by the Institutional Review Board of Washington University School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

This homeless sample was randomly selected from shelters and street routes, using methods previously developed (North, Eyrich, Pollio, & Spitznagel, 2004; Smith, North, & Spitznagel, 1992; Smith, North, & Spitznagel, 1993). Recruitment and baseline assessment of participants occurred between October 1999 and May 2001. The majority (80%) were selected randomly from 12 homeless shelters proportionate to shelter size using randomly-generated computerized schedules. The remaining 20% were recruited from street locations along 16 computer-randomized street routes where homeless people frequently travel; interviewers traversed these routes by foot using randomized starting points and approached all individuals they encountered for potential participation. These individuals were screened for recent housing history, and those eligible were invited to participate in the study. Of 435 eligible homeless individuals invited to participate in the study, 35 did not enroll, yielding a 92% baseline participation rate.

Participants were tracked for two years using methods described elsewhere (North, Pollio, Perron, Eyrich, & Spitznagel, 2012). Of the baseline sample of 400, 29 were classified as ineligible for re-assessment at one or both follow-up points because of death (n=5), severe illness, (n=6), or incarceration (n=18); 288 (72%) were successfully tracked over two years, and of the 371 who were eligible for follow-up reassessments, 255 (68%) were reassessed in both follow-up years with complete data. No significant baseline differences were detected between those tracked and not tracked through the entire two years of study follow-up or between those with all three annual study assessments completed versus those missing one or more assessments in baseline characteristics (North, et al., 2012).

Measures

Study measures provided both self-report and agency-report data. Self report was used to obtain data on individual characteristics, including current and past mental health problems, and services used. Provider agencies reported individual intensity of service utilization and cost information.

Baseline self-report measures

At baseline, a structured interview was administered including sociodemographic sections of the National Comorbidity Study (Kessler, et al., 1994) interview, the substance abuse sections of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Substance Abuse Module for DSM-III-R (Cottler & Compton, 1993), the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (Robins, Cottler, Bucholz, & Compton, 1995), and the Homeless Supplement to the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (North, et al., 2004). These structured interviews elicited detailed information on psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses and substance use patterns, including both lifetime and past year history, as well as amount and types of services used during the previous year. After the interview, a urine sample was obtained and immediately tested using OnTrak Abuscreen rapid assays (Roche Diagnostic Systems Inc., 1991) for the presence of cocaine, opiates, amphetamine, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines.

Follow-up self-report measures

Detailed self-report information on housing status and service use was collected, as well as a urine sample for rapid drug screening, from all participants using detailed interviews at one and two years after the baseline assessments. At each assessment, participants were asked about their housing status and about the amount and types of services they used during the previous year. Participants were considered stably housed at the end of each year if they responded that they had been housed in their own place for the previous 30 days and for most of the past year.

Deriving service costs

Data were collected from four types of agencies providing services to the homeless population: substance abuse treatment agencies, mental health treatment facilities, medical centers (including inpatient, outpatient, and emergency treatment facilities), and homeless shelters. Services in the geographical area where the study was conducted are coordinated through a government-funded agency, the Homeless Services Network Board of the Homeless Service Division of the City of St. Louis Department of Human Services (Coordinated Strategy to Prevent Homelessness, 2012). The Homeless Services Network Board comprises approximately fifty social and human service agencies that meet monthly to coordinate the various types of services offered, to create a comprehensive service continuum to the homeless population in the metropolitan area. Of 29 agencies providing services to this population, 23 participated in this study and one ceased to exist shortly after the study began, yielding an 82% agency participation rate. Among the participating agencies, 12 provided substance abuse programs, 9 provided mental health programs, 6 provided general medical care, and 12 provided night/day sheltering (7 of which also offered substance abuse services and 4 specialized in mental health services) (North, Eyrich, Pollio, & Thirthalli, 2005). Two types of data were collected from participating agencies and individuals: service unit cost data and service utilization data.

Service unit costs

Service unit cost data were obtained and costs were derived using a methodology developed at RTI International, known as the Substance Abuse Services Cost Analysis Program (SASCAP) (Zarkin, Dunlap, & Homsi, 2004). Earlier versions of the SASCAP method have been used to estimate costs in numerous other settings, including methadone (Zarkin, et al., 2004; French, Bradley, Calingaert, Dennis, & Karuntzos, 1994) and other drug abuse treatment programs (Anderson, Bowland, Cartwright, & Bassin, 1998), employee assistance programs (French, Dunlap, Zarkin, & Karuntzos, 1998), and community-based drug prevention interventions (Norton, 1998). The SASCAP method was also used to estimate the service costs of communal services for people with mental illness at the St. Louis Independence Center in a subset of service providers from the current study (Cowell, et al., 2003).

For the current study, the investigative team first worked with service providers of the participating agencies to establish commonly understood definitions of the services provided, activities conducted, and agency job types, to standardize the SASCAP for the participating agencies. Next, data were collected from each program’s director and chief financial officer using the SASCAP. Financial data were collected, including information on staff salaries and benefits, hours worked, non-labor costs, and information on which staff deliver which services and for how long. Then, average hourly wage was estimated and the wage was “loaded” with indirect labor and non-labor costs (e.g., utilities, buildings, supplies, and administrative personnel). Labor inputs were assessed for a typical week of program operations and then extrapolated to the full year. Algorithms were then used to obtain service unit costs per hour.

The SASCAP method has several advantages over alternative costing approaches. First, the instrument is designed to collect economic rather than accounting costs of resources used, and thus includes the full value of all resources, regardless of whether they are donated, subsidized, or entirely paid for by the program. Second, because the instrument collects costs using standardized procedures, costs can be readily aggregated over many service providers. Third, rather than providing only the average cost per client, the method is one of the few that also estimates the cost of a defined unit of a service (e.g., the cost of an hour of individual counseling). As a result, the results can be combined with detailed service utilization data (e.g., hours of individual counseling) to yield comprehensive estimates of service utilization costs. Fourth, the method has been shown to be less burdensome than, but often as accurate as, more intensive methods, such as staff maintaining detailed time diaries (Zarkin, Dunlap, Wedehase, & Cowell, 2008).

Service utilization

To collect data from agencies on services obtained by the study participants, a structured instrument was used. This instrument was tailored to the situation of the agency or service provider, with the unit of analysis being each study participant’s data on service utilization history at that agency during specified periods of time. The instrument consisted of multiple parts, individually selected for each type of service provider: 1) background/characteristics of the provider, including information on staff demographics, education, and level of experience; where services are provided; patterns of referral to and from the provider; and integration and linkage of services to other providers; 2) client-specific information, including date of first and last contact, number of contacts, client’s diagnosis at first and last contact, how the client was referred, list of services provided, family involvement, and the composition of the treatment team; and 3) financial aspects of treatment, including prior authorization (e.g., for hospitalization, what and to whom was reported to third party reimbursement agencies) and financial arrangements (e.g., direct fee for service, salary, capitation fees, and out-of-pocket vs. insurance payment). This instrument required less than 30 minutes to administer, including all subcomponents of the interview. It was administered annually for each participant at each agency covering service use history for that individual in the last 12 months, providing a complete picture of service utilization for each study participant in each study year.

For individual service-use data, access to service records was negotiated independently at each agency, because of differences in procedures and personnel (e.g., full complement of medical records technicians and computerized records systems at large medical centers, vs. handwritten logs of daily guests at shelters). When necessary, agencies were offered project staff assistance in automating service use records. Because baseline study recruitment proceeded for more than one year, individual service use data were collected from agencies quarterly for approximately 100 study participants receiving their annual interviews in each quarter of the year. Once systems were in place for the transfer of data to project staff, the staff contacted all participant agencies quarterly and provided informed consent and release of information forms for the participants interviewed in that quarter. Standardized data collection forms were completed for each client at each agency for the 12 months preceding the date of the study participant interview, and this procedure was repeated quarterly throughout all three waves of data collection. Thus, a complete picture of service utilization was obtained for each participant for the 12 months prior to the baseline interview and the next 24 months ending with the final interview (Pollio, North, Eyrich, Foster, & Spitznagel, 2006).

Creation of variables

Despite efforts to obtain data from agencies in the format developed for collection of the data, several agencies delivered their data in their own unique format. For these agencies, project staff worked to convert data from these agencies into the systematic format being used for this study to allow equivalent data from all the agencies to be merged into a consistent unified database for comprehensive data analysis.

All service use data received were grouped into three general categories: shelter data, State of Missouri Department of Mental Health (DMH) data, and medical/psychiatric provider data. Shelter data were defined as data from any agency that provided a bed or meals, and/or case management. Examples of additional services provided by shelters are individual therapy, group counseling, occupational therapy, vocational rehabilitation, clothing assistance, and referrals for classes or legal services. For agencies providing substance abuse treatment, mental health treatment, or “longer-term” housing for the mentally ill that reported to or received payment from the state DMH, records were collected directly from the DMH. Agencies providing medical care delivered service use data in computerized records.

In this process, various decisions were made to ensure the best fit of the data with the format being utilized, and, when necessary, project staff conferred with data managers of these agencies regarding the format needed for the data to conform to the format of the project’s database.

Some agencies provided data for specific services separately, and this detail permitted the most representative classification of these services in the project database to preserve an accurate calculation of service use and costs. For example, across all medical service agencies, each visit for treatment was categorized as an inpatient, outpatient, or emergency visit and then further designated as a surgical, medical, psychiatric, or substance abuse service. Additional outpatient categories of laboratory, radiological, and ancillary services were included. The cost of all services used at each individual visit was provided by the agency. Thus, whether the service was received at an outpatient neighborhood clinic or at a hospital, all services were categorized in the same manner.

The agency database contained variables describing numbers of units of use and associated costs for a variety of types of services for substance abuse and other mental health and medical care, basic subsistence needs including housing and food, and services such as vocational and housing services to help people attain stable housing. Service-use and cost variables in the merged database created from all individual service-use data provided by agencies were grouped into several main categories of service types. Housing status variables were created to represent participants’ housing status for each year of the study. All of these variables are defined in Table 1. Variables were also created to represent baseline lifetime diagnoses of alcohol use disorder, legal problems, cocaine use disorder, or serious mental illness (SMI). SMI was defined as meeting lifetime criteria for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression. The Consumer Price Index for urban consumers was used to adjust cost estimates to 2013 US dollars.

Table 1.

Main variables used in the analysis

| Service types |

|

Medical services. These include medical emergency care visits, medical inpatient and outpatient care, use of medical supplies, and pharmaceutical services. Psychiatric services. These are services related to assessment and treatment of psychiatric illness, including psychiatric inpatient, outpatient, and emergency care, psychiatric day treatment programs, and psychopharmaceutical services. Specific components of these services include individual and group psychotherapy, psychotropic medication management, and psychiatric case management. Substance abuse services. These services represent substance abuse treatment including inpatient, residential, and outpatient care. Specific components of these services include individual and group psychotherapy for substance abuse and psychotropic medication management for substance abuse as well as self-help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous. Homeless maintenance services. These services relate to the maintenance of individuals while they are homeless, including food (e.g., soup kitchens and food pantries), transportation services, and public and temporary housing services such as nighttime sheltering and transitional housing. Homeless amelioration services. These services relate to the amelioration of homelessness including housing services, vocational rehabilitation, and legal aid services. Total services. These services represent the sum of the five types of service variables above. Acute mental health services. These services refer to acute psychiatric and substance abuse services, including emergency and inpatient care for psychiatric and substance use disorders. Outpatient mental health services. These services refer to psychiatric and substance abuse services provided in non-emergent outpatient settings. |

| Housing status |

| Housed during Year 1. Report of having stable housing for most of the first follow-up year and for the last 30 days of that year. |

| Housed during Year 2. Regardless of housing status in the first year, stable housing was reportedly obtained for most of the second follow-up year and for the last 30 days of that year. |

| Combined Years 1 and 2 housed. Housed status in the first year was concatenated with housed status in the second year to create a variable representing all housed years. (Note that some of the individuals housed in the second year were also housed in the first year and others were not housed in the first year. Hence, this variable does not represent individuals. It represents the total number of housed years among the members of the sample.) |

| Combined Years 1 and 2 unhoused. Unhoused status in the first year was concatenated with unhoused status in the second year to create a variable representing all unhoused years. (Again, this variable represents the total number of unhoused years, not individuals.) |

Data analysis

Agency service utilization data were mapped and aggregated to the list of services reported in the current study. Analyses were conducted in SAS (Version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Because the agencies provided data only on individual services used, it could not necessarily be assumed that lack of service data meant that services were not used, because of the possibility that agencies did not provide all data on the study participants. To manage potentially missing agency data, all missing agency values were first cross referenced with self-reported binary indicators of any service use from participant interviews. If the self-reported service-use data indicated no service use, the corresponding missing agency service use values were assumed to represent zero use of those services. If self-reported service-use data were also missing or if self-reported service-use data indicated some service use the agency data were considered missing. Missing data were imputed by a multiple-imputation analysis (PROC MI in SAS). Multiple imputation procedures replace each missing value with a set of plausible values that represent the uncertainty about the right value to impute using the mean conditional on observed values of other variables that are specified based on known associations with the variables to be imputed. The observed variables specified for the imputation procedure were age, sex, ethnic minority, housing status over the two-year follow-up period, and self-report or urine test evidence of cocaine or alcohol use or diagnosis, because they were associated with service use.

Finally, multiple regression modeling was used to examine differences in costs (dependent variable) by housing status (independent variable), simultaneously controlling for baseline variables including gender, age, race, lifetime alcohol use disorder, lifetime cocaine use disorder, and lifetime diagnosis of serious mental illness. (To address potential effects introduced by non-normal variables in these analyses, a parallel series of Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U tests was conducted for comparison of costs using the same list of dependent variables without covariates, which cannot be used in this type of nonparametric analysis. This procedure did not yield any meaningful differences in findings from those of the multiple regression models, and thus the findings from the multiple regression models are presented with the assumption that the results are not altered by potential non-normality of data.)

Results

Table 2 provides the baseline characteristics of the sample. The majority of the sample had the following demographic characteristics: African-American, male, and having at least a high school education. Many participants had a lifetime history of “legal trouble” (64%), alcohol use disorder (59%), cocaine use disorder (45%), or serious mental illness (32%).

Table 2.

Baseline sample characteristics

| Demographic variable | n/N (%) | mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Males | 187/255 (73%) | |

|

| ||

| Age (years) | 42 (10) | |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 46/249 (18%) | |

| Black | 191/249 (77%) | |

| Other | 12/249 (5%) | |

|

| ||

| High school graduate or equivalent | 149/249 (60%) | |

|

| ||

| Years of education (GED=12) | 12 (2) | |

|

| ||

| Ever married | 114/249 (46%) | |

|

| ||

| Currently married | 13/249 (5%) | |

|

| ||

| Lifetime legal problems | 158/246 (64%) | |

|

| ||

| Recent legal problems | 55/249 (22%) | |

|

| ||

| Lifetime alcohol use disorder | 151/254 (59%) | |

|

| ||

| Lifetime cocaine use disorder | 113/253 (45%) | |

|

| ||

| Lifetime serious mental illness | 82/255 (32%) | |

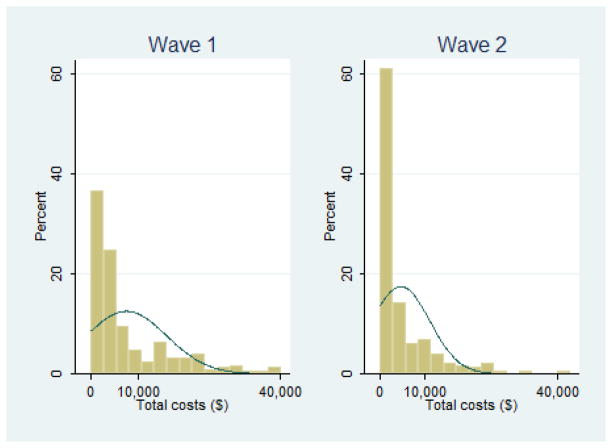

Table 3 provides total costs and costs by service categories by year. The mean (SD) total costs in adjusted dollars of all services per person was $7,811 (10,421) in Year 1 and $5,519 (11,321) in Year 2. There were no significant differences in costs between the two years. The maximum total cost of services used by any individual in the sample in adjusted dollars was $102,698 adjusted in Year 1 and $121,016 in Year 2. The total costs of services utilized by these 255 homeless individuals was $3,393,895 over two years. Figure 1 shows histograms of both waves of data for total costs, with normal plots superimposed. For the sake of legibility, extreme cost values are omitted. The data are skewed because of outliers and the fact that a large proportion of participants had relatively low costs. Nearly all participants, however, used at least some service: 98.4% in year 1 and 94.2% in year 2 (results not shown).

Table 3.

Mean adjusted costs per participant by service domain over time and in housed vs. unhoused years

| Service type | Year 1 (n=255) | Year 2 (n=255) | Housed years 1 and 2 combined (n=190) | Unhoused years 1 and 2 combined (n=320) | All years 1 and 2 combined (n=510) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | 2,568 | 3,461 | 4,147 | 2,342 | 6,029 |

| Psychiatric | 2,150 | 1,155 | 1,260 | 1,186 | 3,305 |

| Substance | 1,642 | 362 | 741 | 1,157 | 2,004 |

| Homeless maintenance | 640 | 183 | 265* | 499* | 1,029 |

| Homeless amelioration | 257 | 2 | 213 | 80 | 324 |

| Total of above | 7,811 | 5,518 | 7,055 | 6,432 | 13,329 |

| Acute behavioral health | 2,671 | 443 | 946 | 1,920 | 3,114 |

| Outpatient mental health | 295 | 155 | 197 | 214 | 450 |

Housed and unhoused years were compared in multivariate logistic regressions (one model for each category listed in the table) predicting cost, controlling for sociodemographics (gender, age, ethnic minority status) and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses (alcohol use disorder, cocaine use disorder, serious mental illness) at baseline,

p<.05.

Figure 1.

Histogram and normal plot of wave 1 and wave 2 total costs

Note: Values greater than $50,000 omitted (1 in wave 1, 3 in wave 2).

Service costs were compared for the service categories in housed and unhoused years. In a series of multivariate regression models controlling for baseline variables that were significantly associated with services in the nonparametric bivariate analyses, including sociodemographic characteristics (sex and ethnic minority status) and lifetime psychiatric diagnosis (alcohol use disorder, cocaine use disorder, and serious mental illness), to compare costs (dependent variable) by current year housing status (independent variable), only homeless maintenance service costs varied significantly by housing status, with greater cost in unhoused years (β=262.27, SE=76.71, df=1, t=3.42, p<.001). Neither total service costs nor costs of service categories differed significantly between the two study years. Also, there were no differences by housing status in total costs or in costs of service categories when the two years were examined separately.

Discussion

A signal contribution of the current study is that service costs were accurately derived across a large set of service providers. This approach closely tracked the value of resources used. To our knowledge, applying the SASCAP costing approach to multiple agency domains in a single study has not yet been accomplished in the published literature. Using a consistent method of cost data across several service sectors ensures standardization of the types of data included in cost estimates and derivation of the estimates across sectors. This standardization is particularly important for homeless populations that have multiple types of services needs and utilize other systems, necessitating the collection of comparable data across various service sectors for accurate costing.

The costing method used in the current study represents an alternative and possibly preferable approach over the most frequently used current alternative, deriving costs from administrative billing or reimbursement data. Deriving costs from administrative data does not consider the value of the resources used to provide services, reflecting ongoing concerns about the adequacy of third-party reimbursement in the literature (e.g., Cunningham, McKenzie, & Taylor, 2006). The limitation of administrative sources for assignment of unit costs was apparent in the current study, which demonstrated that multiple funding sources pay for the same services in different agencies (some within the same sectors of care), and that there is substantial variation in reimbursement rules and rates across those funding sources. For example, mental health services may be funded by both Medicaid and local sources, whereas substance abuse services may be funded by a federal block grant. These funding sources vary in many dimensions, even insofar as which providers may be qualified to bill for services (e.g., Buck, 2011).

The research sample included in this study of homeless service costs is more representative than samples provided by administrative databases. Administrative databases include only individuals who use the services; individuals not using the services are not represented. Costs per person are thus overestimated by an indeterminate amount based on the amount of underrepresentation of individuals with zero service use. To an extent, combining multiple administrative data sets across multiple sectors of care (e.g., as done by Poulin and colleagues) in the costing exercise increases the representation of very low service utilizers, because individuals using just one service unit in one database are included in the overall sample. Even using this method, however, the cost-per-person estimates are not free of this source of inflation caused by non-inclusion of zero service users.

In the current study, although the analysis of costs across time periods and for subpopulations yielded relatively few significant differences, the correspondence of the findings with the published literature on service use and the intuitive nature of the specific differences found suggests validity for these methods. For example, higher homeless maintenance costs (e.g., for shelter use) associated with homelessness compared to having stable housing is logical, because people without housing have greater needs for maintenance services.

Although the overall cost findings reported in the current study are strikingly close to the one other population-based study to date (Poulin, et al., 2010) (both report approximately $7,000/year in aggregate individual service costs), this appears to be more coincidental than representing a common end point of these two methodologies. At a minimum, the previously noted underrepresentation of service nonusers in administrative databases inflates the cost per person by an uncertain amount. Additionally, chronically homeless populations are likely to have higher costs, and the Poulin et al. study was limited to chronic homelessness. Although some oversampling of chronic homeless is unavoidable is community samples, the current study also included participants who are more recently homeless.

One weakness shared by both the current study and the Poulin et al. study is the lack of data collection for a significant sector of care—in this one, the criminal justice system, and in Poulin et al. study, the medical care sector. These omissions suggest that both studies may have underestimated the total annual cost per person. Because the omitted sectors were significant cost drivers, both studies have likely underestimated aggregate costs substantially. It is also likely that omission of sectors of care plays an important role in the comparison between housed and unhoused individuals. In the current study, costs in every sector of care except medical decreased over time. Because medical costs were the single largest aggregate sector cost, their inclusion could have changed the significance of the Poulin et al. study finding that people who gain housing have lower service costs than those who do not. Nevertheless we caught approximately 80% of all mainstream providers in the geographic region.

Additional study limitations deserve mention. Some agencies declined to participate in the research and thus their data were not included; in these cases, unit cost estimates from other agencies were used. The current study uses a combination of self-report and administrative report is used, and to the degree that these are not concordant, bias may result (Pollio et al., 2006). However, the current study mitigates this by only using self-report data for indicators of whether any service of a particular type is used; moreover, there is no indication that any bias would be different across housing groups. Some client-level agency service use data were missing from participating agency records provided to the study, this being due to the manner in which the data were collected. The current study could not reliably estimate what proportion of service use data agreed with the self-report data because the available data could not be used to distinguish between a missing data point and a zero. The administrative service data report service use and intensity but not why previously engaged clients did not receive services for a particular period of time. Nor could these data indicate why clients in the study sample had never received a service. Although, state-of-the-art imputation methods were used in the case of missing administrative data, they are potentially subject to error. Data received in proprietary formats had to be converted to the standardized formats used for the study. Although quality assurance procedures were followed, converting the data to a standardized format is an extra step in the analysis that may have introduced error. Although the comparison of the housed and unhoused years with cost variables controlled for a rich set of covariates, it is possible that additional observed or unobserved factors correlated both with service costs and housing status were not included in the models. Finally, participant costs (e.g. opportunity cost of time) and benefits (e.g. value of utility gained from engaging in services) were omitted, as is typical in the health services research literature.

Although a decade has passed since the data for this study were collected, the methods used to derive costs are still state-of-the-art for addiction services. Any potential effects of the passage of time on the findings are unknown; this is an issue that is inherent in all data collected, whether the findings are published in 2003 or a decade later.

The current study represents an important step forward in developing methods that accurately represent costs associated with services for homeless populations. Compared to using administrative cost data, data collection requires study staff to be trained and is time consuming. Further research is required to clarify the gains in precision from this improved method over less extensive costing methods using administrative data. Future research needs to incorporate all sectors of care in estimating aggregate costs for homeless populations. This recommendation holds for naturalistic costing studies like the current one as well as cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit intervention studies. Because the homeless samples in this and other studies include a small number of outliers with extremely high service costs, future research is required to help understand who these individuals are and the factors associated with their very high costs. Finally, because the variables used in the comparison here have intrinsic limitations, future research is needed to examine cost differences for more nuanced questions. For example, the analysis here assumed that being housed is a monolithic construct. Inquiry into whether certain housing situations have greater impact on other service costs may help determine housing policy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Brian S. Fuehrlein, Email: fuehrlein@ufl.edu, University of Florida Department of Psychiatry, PO Box 100383, Gainesville, FL 32610.

Alexander J. Cowell, RTI International, 3040 Cornwallis Rd, PO Box 12194, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-2194.

David E. Pollio, University of Alabama, School of Social Work, 25 Little Hall, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487-0314.

Lori Y. Cupps, Washington University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, 660 S Euclid Ave. Campus Box 8134, St. Louis, MO 63011.

Margaret E. Balfour, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, TX 75390.

Carol S. North, VA North Texas Health Care System and University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center, 6363 Forest Park Rd., Suite 651, Dallas, TX 75390-8828.

References

- Anderson DW, Bowland BJ, Cartwright WS, Bassin G. Service-level costing of drug abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15(3):201–211. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggett TP, O’Connell JJ, Singer DE, Rigotti NA. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: A national study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(7):1326–1333. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Kee R, Buchanan D, Sadowski LS. Comparative cost analysis of housing and case management program for chronically ill homeless adults compared to usual care. Health Services Research. 2012;47(1 part 2):523–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck JA. The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the affordable care act. Health Affairs. 2011;30(8):1402–1410. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coordinated Strategy to Prevent Homelessness. The United States Conference of Mayors; Apr 30, 2012. http://www.usmayors.org/bestpractices/homeless/st_louis_mo.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Compton WM. Advantages of the CIDI family of instruments in epidemiological research of substance use disorders. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1993;3:109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cowell AJ, Pollio DE, North CS, Stewart AM, McCabe MM, Anderson DW. Deriving service costs for a clubhouse psychosocial rehabilitation program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2003;30(4):323–340. doi: 10.1023/a:1024085200791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culhane DP, Metraux S, Hadley T. Public service reductions associated with the placement of homeless people with severe mental illness in supportive housing. Housing Policy Debate. 2002;13:107–163. [Google Scholar]

- Culhane DP, Gross KS, Parker WD, Poppe B, Sykes E. Accountability, cost-effectiveness, and program performance: progress since 1998. National Symposium on Homelessness Research.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham P, McKenzie K, Taylor EF. The struggle to provide community-based care to low-income people with serious mental illnesses. Health Affairs. 2006;25(3):694–705. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischman S. Chronic Disease in the Homeless. New York: Springer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- French MT, Bradley CJ, Calingaert B, Dennis ML, Karuntzos GT. Cost analysis of training and employment services in methadone treatment. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1994;17(2):107–120. [Google Scholar]

- French MT, Dunlap LJ, Zarkin AG, Karuntzos GT. The costs of an enhanced employee assistance program (EAP) intervention. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1998;21:227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer TP, Stefancic A, Ettner SL, Manning WG, Tsemberis A. Effect of full-service partnerships on homelessness, use and costs of mental health services, and quality of life among adults with serious mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):645–652. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SW, Weaver J, Aubry T, Hoch JS. Hospital costs and length of stay among homeless patients admitted to medical, surgical, and psychiatric services. Medical Care. 2011;49(4):350–354. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318206c50d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K, Colson PW, Holter MC, Lin S, Valencia E, Susser E, Wyatt RJ. Cost-effectiveness of critical time intervention to reduce homelessness among persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(6):884–890. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.6.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the united states. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno E, Rothbard AB, Averyt J, Culhane DP. Homelessness among persons with serious mental illness in an enhanced community-based mental health system. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:1012–1016. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.8.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(2):200–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community based study. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(5):778–784. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, Atkins DC, Burlingham B, Lonczak HS, Tanzer K, Ginzler J, Clifasefi SL, Hobson WG, Marlatt A. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(13):1349–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell JV, Seitz RS, Harada JK, Kobayashi J, Sasaki VK, Wong C. Hospitalization in an urban homeless population: the Honolulu urban homeless project. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1992;116(4):299–303. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-4-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez TE, Burt MR. Impact of permanent supportive housing on the use of acute care health services by homeless adults. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:992–999. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Eyrich KM, Pollio DE, Foster DA, Cottler LB, Spitznagel EL. The homeless supplement to the diagnostic interview schedule: test-retest analyses. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:184–191. doi: 10.1002/mpr.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Eyrich KM, Pollio DE, Spitznagel EL. Are rates of psychiatric disorders in the homeless population changing? American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:103–108. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Pollio DE, Perron B, Eyrich KM, Spitznagel EL. The role of organizational characteristics in determining patterns of utilization of services for substance abuse, mental health, and shelter by homeless people. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;3:571–586. [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Black M, Pollio DE. Predictors of successful tracking over time in a homeless population. Social Work Research. 2012;36(2):153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Norton E. Threshold Analysis of AIDS Outreach and Intervention. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell J. The Boston Healthcare Program. Boston: 1999. Utilization and Costs of Medical Services by Homeless Persons: A Review of the Literature and Implications for the Future. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Bruggman AR, Haukoos JS. Out-of-hospital and emergency department utilization by adult homeless patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007;50(6):646–652. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollio DE, North CS, Eyrich KM, Foster DA, Spitznagel EL. A comparison of agency-based and self-report methods of measuring services across an urban environment by a drug-abusing homeless population. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2006;15:46–56. doi: 10.1002/mpr.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin SR, Maguire M, Metraux S, Culhane DP. Service use and costs for persons experiencing chronic homelessness in Philadelphia: a population-based study. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(11):1093–1098. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RO, Bergstralh EJ, Schmidt L, Jacobsen SJ. Comparison of self-reported and medical record health care utilization measures. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1996;49(9):989–995. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for the DSM-IV (DIS-IV) Washington University; St. Louis: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Roche Diagnostic Systems Inc. Abuscreen OnTrak Rapid Assays for Drug Abuse User’s Manual and Product Literature. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R. Cost-effectiveness of services for mentally-ill homeless people: the application of research to policy and practice. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1563–1570. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salit SA, Kuhn EM, Hartz AJ, Vu JM, Mosso AL. Hospitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(24):1734–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806113382406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EM, North CS, Spitznagel EL. A systematic study of mental illness, substance abuse, and treatment in 600 homeless men. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 1992;4:111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Smith EM, North CS, Spitznagel EL. Alcohol, drugs and psychiatric comorbidity among homeless women: an epidemiologic study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1993;54:82–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkin GA, Dunlap LJ, Homsi G. The substance abuse services cost analysis program (SASCAP): a new method for estimating drug treatment services costs. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2004;27(1):35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zarkin GA, Dunlap LJ, Wedehase B, Cowell AJ. Evaluation and Program. 2008. The effect of alternative staff time data collection methods on drug treatment service cost estimates. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]