Abstract

Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) is a multifunctional protein with important roles in regulation of inflammation and angiogenesis. It is produced by various cell types, including endothelial cells (EC). However, the cell autonomous impact of PEDF on EC function needs further investigation. Lung EC prepared from PEDF-deficient (PEDF−/−) mice were more migratory and failed to undergo capillary morphogenesis in Matrigel compared with wild type (PEDF+/+) EC. Although no significant differences were observed in the rates of apoptosis in PEDF−/− EC compared with PEDF+/+ cells under basal or stress conditions, PEDF−/− EC proliferated at a slower rate. PEDF−/− EC also expressed increased levels of proinflammatory markers, including vascular endothelial growth factor, inducible nitric oxide synthase, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, as well as altered cellular junctional organization, and nuclear localization of β-catenin. The PEDF−/− EC were also more adhesive, expressed decreased levels of thrombospondin-2, tenascin-C, and osteopontin, and increased fibronectin. Furthermore, we showed lungs from PEDF−/− mice exhibited increased expression of macrophage marker F4/80, along with increased thickness of the vascular walls, consistent with a proinflammatory phenotype. Together, our data suggest that the PEDF expression makes significant contribution to modulation of the inflammatory and angiogenic phenotype of the lung endothelium.

Keywords: angiogenesis, inflammation, thrombospondin, Wnt signaling, adherens junctions

angiogenesis is a multistep process involving the growth of new blood vessels from preexisting capillaries, and it is crucial for the normal development and function of lung. Angiogenesis is tightly regulated by a balanced production of pro- and antiangiogenic factors. Alterations in this balance may impact proangiogenic and proinflammatory properties of vasculature and contribute to various pathologies (15). Survival, adhesion, proliferation, tube formation, and migration of endothelial cells (EC) are essential in angiogenesis (17). Function of EC in angiogenesis is modulated by production of various pro- and antiangiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), thrombospondin-1 (TSP1), and pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) (23, 35, 46). However, the contribution of these factors to regulation of lung vascular homeostasis and pathologies remains poorly understood.

PEDF is a 50-kDa glycoprotein and belongs to serine protease inhibitor family of proteins (3, 36). It was first identified in cultured fetal retinal pigment epithelial cells (41). PEDF is also expressed in other ocular cell types, including Müller cells, pericytes, and EC (40). PEDF influences the function and pathogenesis of various tissues, including liver, kidney, heart, prostate, and lung, due to its various biological activities (8, 12, 22, 43). PEDF is an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and is neuroprotective. It inhibits the migration of EC in response to proangiogenic factors (10) and induces apoptosis of human EC by activating p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and caspases (5, 22). Increased PEDF expression in the retina results in attenuation of neovascularization through modulation of canonical Wnt signaling (30). PEDF also has anti-inflammatory activity, and its expression in diabetic rat inhibits the expression of proinflammatory factors through inhibition of NF-κB activity (45).

PEDF plays an important role in regulation of angiogenesis and inflammation through its coordinated activity with proangiogenic and inflammatory factors, including VEGF. Alterations in this coordinated activity and dysfunction in the regulation of VEGF and PEDF expression have been implicated in pathogenesis of various diseases with a neovascular component, including age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and cancer. These alterations have been generally associated with increased expression of VEGF, while that of PEDF is suppressed (1, 46), favoring a proangiogenic and inflammatory state. However, the contribution of such alterations to various lung pathologies requires further investigation.

An important role for VEGF in lung development, integrity, and function has been previously demonstrated. Attenuation of VEGF activity, through inhibition of its receptor in the lung, results in increased apoptosis and development of emphysema (21). However, the role of PEDF in lung development and vascular homeostasis has not been previously studied. To gain new insight into PEDF function in the lung, we investigated the specific role of PEDF in the lung endothelium. We prepared lung EC from PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice. Here we show PEDF deficiency increased EC migration along with increased adhesion to various extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. We also showed that PEDF deficiency was associated with attenuation of capillary morphogenesis of lung EC. Mechanistically, PEDF−/− lung EC expressed increased levels of inflammatory markers, including VEGF, VCAM-1, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), concomitant with increased nitric oxide (NO) production. Furthermore, we showed that the levels of inflammatory proteins were altered, and the thickness of vessel wall was increased in lungs from PEDF−/− mice. Thus endothelium expression of PEDF is essential for maintaining the inflammatory and angiogenic properties of the lung.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals and culture of lung EC.

All experiments were carried out in accordance with and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Immortomice expressing a temperature-sensitive SV40 large T antigen were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). The PEDF−/− mice were crossed with the Immortomice and screened as previously described (51). Lungs from three 4-wk-old PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− Immortomice were dissected and kept in serum free-Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing penicillin and streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The lungs were pooled, rinsed with DMEM, minced into small pieces in a 60-mm tissue culture dish using sterile razor blades, and digested with 5 ml of collagenase type I (1 mg/ml in serum-free DMEM; Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) for 45 min at 37°C. After digestion, DMEM with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added, and cells were collected by centrifugation. The cellular digests were filtered through a double layer of sterile 40-μm nylon mesh (Sefar America, Hanover Park, IL) and centrifuged at 400 g for 10 min to collect cells. Cells were washed twice with DMEM containing 10% FBS and were resuspended in 1.5 ml of medium (DMEM with 10% FBS) containing anti-rat magnetic beads coated with anti-platelet endothelial cell adhesion modecule 1 (PECAM-1) antibody (MEC13.3; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), as previously described (37). The cells and beads were incubated at 4°C for 1 h with continuous mixing. After affinity binding, magnetic beads were washed six times with DMEM with 10% FBS. The bound cells were plated into a single well of a 24-well plate coated with 2 μg/ml of human fibronectin (BD Biosciences) using 0.5 ml of EC growth medium. The EC growth medium is DMEM containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 2 mM sodium pyruvate, 20 mM HEPES, 1% nonessential amino acids, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin, freshly added heparin at 55 U/ml (Sigma), 100 μg/ml endothelial growth supplement (Sigma), and murine recombinant interferon-γ (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at 44 U/ml. Cells were incubated at 33°C with 5% CO2 and progressively passaged to larger plates. Cells were normally maintained in 60-mm dishes coated with 1% gelatin prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The majority of experiments described here were performed with two separate isolations of cells and repeated twice.

RNA purification and real-time quantitative PCR analysis.

The total RNA from PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC was extracted using mirVana PARIS kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To extract total RNA from lung tissue, lung was removed from postnatal day 28 (P28) PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice. Total RNA was extracted from lung tissue using mirVana PARIS kit (Invitrogen). cDNA synthesis was performed from 1 μg of total RNA using Sprint RT Complete-Double PrePrimed kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). One microliter of each cDNA (dilution 1:10) was used as a template in quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays, performed in triplicate of three biological replicates on Mastercycler Realplex (Eppendorf) using the SYBR-Green qPCR Premix (Clontech). Amplification parameters were as follows: 95°C for 2 min; 40 cycles of amplification (95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 40 s); dissociation curve step (95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 15 s, 95°C for 15 s). Primer sequences for PEDF were 5′-GCCCAGATGAAAGGGAAGATT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGGGCACTGGGCATTT-3′ (reverse); for interleukin (IL)-1β, 5′-GTTCCCATTAGACAACTGCACTACA-3′ (forward), and 5′- CCGACAGCACGAGGCTTTT-3′ (reverse); and for monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, 5′-GTCTGTGCTGACCCCAA GAAG-3′ (forward), and 5′-TGGTTCCGATCCAGGTTTTTA-3′ (reverse). Standard curves were generated from known quantities for each of the target gene of linearized plasmid DNA. Ten times dilution series were used for each known target, which were amplified using SYBR-Green qPCR. The linear regression line for nanograms of DNA was determined from relative fluorescent units at a threshold fluorescence value to quantify gene targets from cell extracts by comparing the relative fluorescent units at the threshold fluorescence value to the standard curve, normalized by the simultaneous amplification of RpL13a, a housekeeping gene. Primer sequences for RpL13a were 5′-TCTCAAGGTTGTT CGGCTGAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAGACGCCCCAGGTA-3′ (reverse).

Cell proliferation and apoptosis.

For cell proliferation assays, cells (1 × 104) were plated in triplicate in multiple sets of 60-mm tissue culture plates. Cells were fed every other day for 2 wk, and the cell numbers were determined on the days not fed in triplicates using a hemocytometer. Apoptotic cell death was determined by TdT-dUTP terminal nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining. TUNEL staining was performed using Click-iT TUNEL, as recommended by the supplier (Invitrogen). Positive cells were counted using a fluorescence microscope and reported as a percentage of apoptotic cells. The rate of DNA synthesis was measured using Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 kit, as recommended by the supplier (Invitrogen). The assay measures incorporation of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU), a nucleoside analog of thymidine, during cell proliferation. PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− lung EC were plated at 5 × 105 cells on 60-mm tissue culture dishes and were incubated with 10 μM EdU in PC medium for 1 h at 33°C. DNA synthesis was analyzed by measuring incorporated EdU using the FACSscan Caliber flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Ten thousand cells were analyzed for each sample, and three independent experiments were performed with two different isolation of EC.

Indirect immunofluorescence staining.

Lung EC (1 × 105) were plated on glass coverslips coated with 2 μg/ml of fibronectin. The next day, cells were rinsed with PBS, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min on ice, washed twice with PBS. Cells were incubated in PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature for permeabilization. After washing cells with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) twice, cells were incubated with anti-vinculin (1:100; Sigma), FITC-phallodin (1:200; Sigma), and DAPI (Invitrogen, D1306; 10 μg/ml) for 40 min at 37°C. Anti-VE-cadherin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and β-catenin (BD Biosciences) were also used. After washing three times with PBS, cells were incubated with appropriate CY3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) at 37°C for 40 min. Cells were washed three times with PBS, mounted, and photographed using a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (Axiophot, Zeiss, Germany) equipped with a digital camera.

Scratch wound assays.

Cells (4 × 105) were plated on 60-mm tissue culture dishes and allowed to reach confluence (2–3 days). After aspirating the medium, cell layers were wounded using a 1-ml micropipette tip. Plates were then rinsed with PBS fed with growth medium containing 5-FU (100 ng/ml, Sigma) to exclude the potential contribution of differences in cell proliferation. The wounds were photographed at 0, 24, and 48 h. The distance migrated as percent of total distance was determined by taking five equally spaced measurements at time 0 and at each subsequent time point for each wound and calculating the distance migrated as a percentage of the total wounded area. Each sample was performed in triplicate on at least three independent occasions using two different isolations of EC, with similar results.

Transwell migration assays.

Transwell filters (Costar 3422) were coated with 2 μg/ml of fibronectin in PBS overnight at 4°C, rinsed with PBS, and then blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. Serum-free DMEM (0.5 ml) was added to a well of a 24-well plate, and the Transwell was inserted into each well. Cells (1 × 105) in 100 μl of serum free-medium were added to the top of each Transwell membrane and incubated for 3 h at 37°C in a tissue culture incubator. Following incubation, the medium was aspirated, and the upper side of the membrane wiped with a cotton swab. The cells that had migrated through the membrane were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Ten high-power fields (×200) were counted for each condition, and the average number of cells migrated per field was determined.

Capillary morphogenesis assays.

Tissue culture plates (35 mm) were coated with 0.5 ml of Matrigel (10 mg/ml; BD Biosciences) and allowed to harden at 37°C for at least 30 min. Cells were removed by trypsin-EDTA, washed with DMEM containing 10% FBS, and resuspended at 2 × 105 cells/ml in EC growth medium without serum. Cells (2 × 105) in 2 ml were applied to the Matrigel-coated plates, incubated at 33°C, and photographed after 18 h with a Nikon microscope in digital format. For quantitative assessment of the data, the mean numbers of branch points were determined by counting the number of branch points in five high-power fields (×100). Longer incubation times did not further improve the degree of capillary morphogenesis.

Cell adhesion assays.

Various concentrations of fibronectin, vitronectin, collagen type I, and collagen type IV (BD BioSciences) prepared in TBS (20 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) with Ca2+ and Mg2+ (2 mM each; TBS with Ca/Mg) were coated on 96-well plates (50 μl/well; Nunc Maxisorbe plates, Fisher Scientific) overnight at 4°C. Plates were rinsed four times with 200 μl of TBS with Ca/Mg and blocked with 200 μl of 1% BSA prepared in TBS with Ca/Mg for at least 1 h at room temperature. Cells were prepared using 2 ml of cell dissociation solution (Sigma), washed with TBS, and resuspended at 5 × 105 cells/ml in freshly prepared HBS (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6, and 4 mg/ml BSA). After blocking, plates were rinsed with TBS with Ca/Mg once, and 50 μl of cell suspension were added to each well containing 50 μl of TBS with Ca/Mg. The cells were allowed to adhere to the plate for 2 h at 37°C. The nonadherent cells were removed by gently washing the plate four times with TBS containing Ca/Mg until there were no cells left in wells coated with BSA. The number of adherent cells in each well was quantified by measuring the cellular phosphatase activity, as previously described (51). All samples were done in triplicates.

FACScan analysis.

Monolayers of lung EC on 60-mm tissue culture dishes were washed once with PBS containing 0.04% EDTA and incubated with 2 ml of nonenzymatic cell dissociation solution (Sigma). Cells were removed from the dish, washed with PBS, fixed with 2% PFA on ice for 30 min, and washed with PBS. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in 0.5 ml of TBS with 1% BSA containing an appropriate dilution of primary antibodies, as recommended by the supplier, and incubated on ice for 30 min. For vascular EC markers, cells were incubated with anti-PECAM-1, anti-endoglin, anti-ICAM-2 (BD Biosciences), anti-VE-cadherin (Enzo Life Sciences), anti-ICAM-1 (Santa Cruz; sc-1511), anti-VCAM-1 (Millipore; CBL1300), anti-VEGF receptors (VEGFR1 and VEGFR2; R&D Systems), or FITC-conjugated B4 lectin (Sigma). For integrin expression analysis, anti-α1-integrin (BD Biosciences), anti-α2- (H293, sc-9089), α3- (N-19, sc-6588), α5- (C-19, sc-6593), α7- (R&D Systems), β1- (M-106, sc-8678), and β8-integrin (H-160, sc-25714) (Santa Cruz) and α6- (MAB1378) and αvβ3-integrin (MAB1976Z) (Millipore) antibodies were used. The cells were washed with TBS containing 1% BSA and then incubated with the appropriate FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200) on ice for 30 min. After the incubation, the cells were washed twice with TBS containing 1% BSA and resuspended in 0.5 ml of TBS containing 1% BSA. FACScan analysis was performed on a FACScaliber flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Western blot analysis.

Cells (6 × 105) were plated in 60-mm tissue culture dishes and incubated until they reached ∼90% confluence (2–3 days). The cells were then rinsed once with serum-free DMEM and incubated in EC growth medium without serum for 2 days. Conditioned medium (CM) was collected and centrifuged to remove cell debris. The cells were also lysed in 0.1 ml of lysis buffer [50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2, with 1% Triton X-100, 1% NP-40, and protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL)]. For lysate from lung tissue, lungs were removed from P28 PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice. The lung tissue was rinsed with TBS and lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were determined using bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Samples were adjusted for protein content, mixed with an appropriate volume of 6 × SDS-sample buffers, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (4–20% Tris-glycine gels, Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and the membrane was blocked with blocking buffer (0.05% Tween 20 and 5% skim milk in TBS). For phospho-endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), the membrane was blocked in 5% BSA in TBS buffer containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST). The following primary antibodies were used: anti-tenacin-C (AB19013; Millipore); fibronectin (H-300, sc-9068) and eNOS (C-20, sc-654) (Santa Cruz); osteopontin and SPARC (R&D Systems); TSP1 (A6.1, Neo Markers, Fremont, CA); phospho-eNOS (Ser 1177) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA); β-catenin, iNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), and TSP2 (BD Biosciences); zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and occludin (Invitrogen); F4/80 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA); and milk fat globule epidermal growth factor-8 (MFG-E8) (R&D Systems). Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer (as recommended by the supplier) and incubated with the membrane overnight at 4°C. Blots were washed with TBST and incubated with appropriate secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody. The blots were then washed with TBST and developed by enhanced chemiluminescence method (GE Healthcare). The blot was stripped and incubated with anti-β-actin (Sigma) antibody for loading control.

PEDF expression.

The lenti viruses expressing GFP or PEDF were obtained from Dr. Olga Volpert (Northwestern University). For transduction of PEDF−/− lung EC, lenti viruses at multiplicity of infection of 20 or 40 were added to the culture medium in the presence of 8 μg/ml of polybrene (Sigma) for overnight. The next day, medium was removed, and cells were fed with fresh medium. After 72 h, PEDF level was determined by Western blot analysis.

Analysis of VEGF levels.

VEGF protein levels produced by PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC were determined using a Mouse VEGF Immunoassay kit (R&D Systems). Cells were plated at 6 × 105 cells on 60-mm tissue culture dishes and allowed to reach ∼90% confluence. The cells were then rinsed once with serum-free DMEM and were grown in serum-free medium for 2 days. CM was centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min to remove cell debris, and 50 μl were used in the VEGF immunoassay. The assay was performed in triplicates, as recommended by the manufacturer, and was normalized to the number of cells. The amount of VEGF was determined using a standard curve generated with known amounts of VEGF in the same experiment. These experiments were repeated three times with two different isolations of cells.

Analysis of NO levels.

Lung EC (5 × 103 cells in 100 μl per well) were plated on black wall clear bottom 96-well plates to measure NO level and cell number. The next morning, the medium was changed to EC medium containing 30 μM 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate (Invitrogen; D-23842). Following 40-min incubation at 33°C, the medium was replaced with fresh EC medium, and the incubation continued for 20 min. The wells were washed with TBS, each well was resuspended in 100 μl of TBS, and the absorbance was read at 495/515 nm in triplicates and repeated twice with similar results. The number of viable cells in each well was measured by a colorimetric determination at 490 nm using CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell proliferation assay (Promega, Madison, WI).

Processing of lungs for histological studies and immunohistochemistry.

Lungs from P28 PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice were removed, inflated, fixed with formalin overnight, and processed for paraffin sectioning. Sections (5 μm each) were placed on slides, and some slides were stained with movat pentachrome. Four PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice were killed, and two sections were prepared from each mouse. Pictures of randomly selected pulmonary arterial and venule in matched regions of slides were taken in eight different high-power fields (×200). Areas of inner and outer vessel were measured using Image J software (National Institutes of Health; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). Vessel thickness was calculated by subtracting the area of inner vessel from the area of outer vessel. For immunohistochemical staining, four PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice were killed, and multiple sections from same regions per each mouse were examined. Paraffin sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated. Antigen unmasking was performed using antigen-unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sections were then washed in PBS and incubated for 15 min in PBS blocking buffer (PBS containing 1% BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 0.2% skim milk powder). The sections were incubated overnight with anti-PECAM-1 (1:150; R&D Systems). The sections were then incubated with indocarbocyanine (CY3)-labeled secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and photographed. The intensity of signal was determined by measuring the area of fluorescence via Image J, and the ratio of vascular area was determined via AngitoTool (52), using equal-timed exposures of four high-power fields (×400).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical differences between two groups were evaluated with Student's unpaired t-test (two-tailed). For the comparison of multiple groups, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett's test was performed. Mean values ± SE are shown. P < 0.05 is considered significant.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of lung EC from PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice.

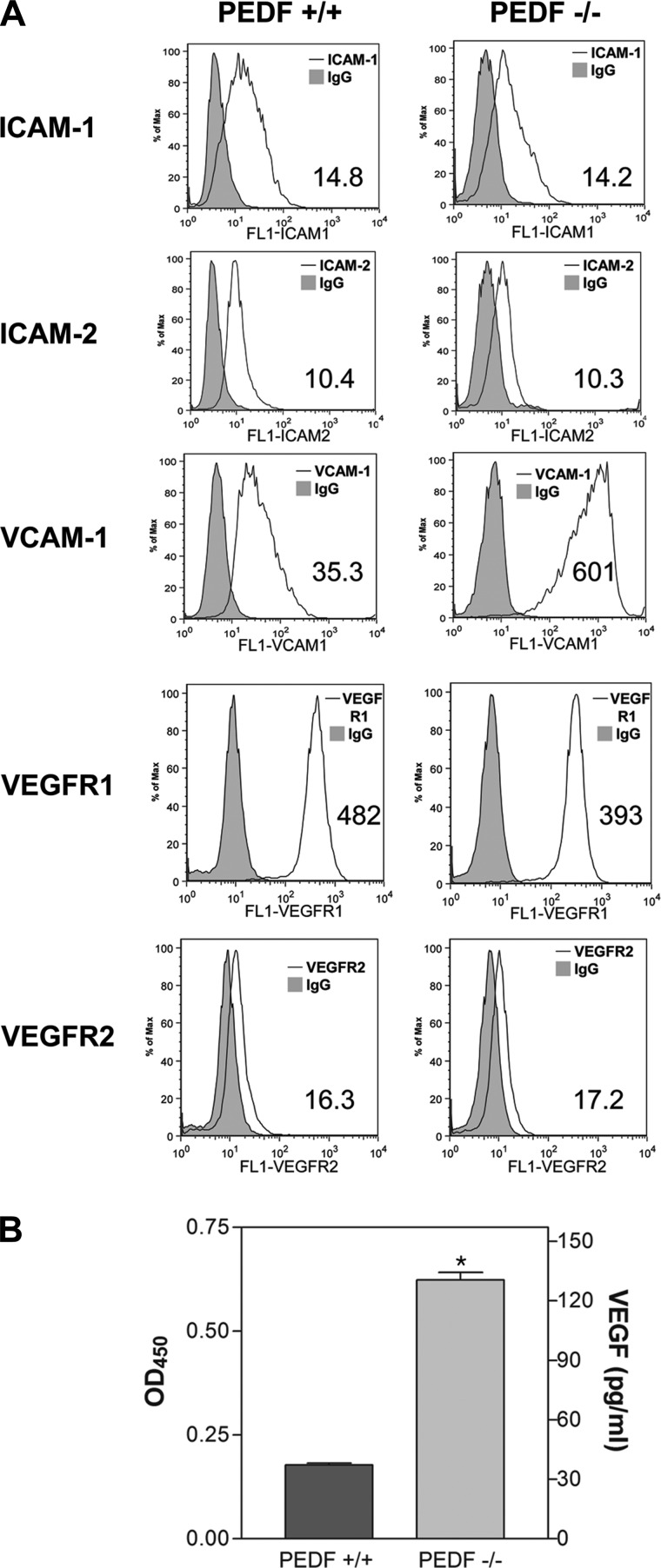

Figure 1A shows the morphology of EC prepared from PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− Immortomice. PEDF+/+ EC showed more elongated and spindly morphology compared with PEDF−/− EC when plated on gelatin-coated plates. Next, we determined PEDF mRNA expression level in PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC by real-time qPCR analysis. In PEDF+/+ EC, mRNA of PEDF was expressed, whereas it was not expressed in PEDF−/− EC as expected (Fig. 1B). We also determined the levels of PEDF secreted by PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC. In CM from PEDF+/+ EC, PEDF was detected by Western blot analysis, but not detected in CM from PEDF−/− EC as expected (Fig. 1C). We measured expression levels of EC markers to confirm that these cells maintain their EC characteristics (Fig. 1D). PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC exhibited a similar level of VE-cadherin expression, while endoglin and B4-lectin levels were lower in PEDF−/− EC compared with PEDF+/+ cells. PECAM-1 expression was also lower in PEDF−/− EC compared with PEDF+/+ EC (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, we determined the expression level of ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 by FACS analysis. PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− cell showed similar level of ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 expression (Fig. 2A). However, the level of VCAM-1 in PEDF−/− EC was higher than in PEDF+/+ EC (Fig. 2A). We also measured expression levels of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 in both cell types. Expression levels of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 were similar in PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC (Fig. 2A). However, PEDF−/− EC secreted four times more VEGF compared with PEDF+/+ EC (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 1.

Isolation and characterization of mouse lung microvascular endothelial cells (EC). A: pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF)+/+ and PEDF−/− lung EC cultured on gelatin-coated plates. Cells were photographed using a phase microscope in digital format at low magnification (top; ×40) and high magnification (bottom; ×100). Please note the elongated, spindly morphology of PEDF+/+ cells compared with PEDF−/− cells (arrowheads). B: mRNA expression of PEDF in lung EC prepared from PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice. Three independent experiments were performed with triplicate samples. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). P < 0.05. C: level of PEDF in conditioned medium (CM) collected from lung EC. PEDF+/+ lung EC secreted PEDF in CM, whereas PEDF−/− lung EC did not. D: lung EC prepared from PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice were examined for expression of endoglin, B4-lectin, VE-cadherin, and platelet EC adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM-1) by FACScan analysis. The shaded areas show staining in the presence of control IgG. The geometric mean values are shown in the bottom corner of each graph. Similar results were observed with another isolation of EC.

Fig. 2.

Expression of EC markers and production of VEGF in lung EC. A: expression of other EC markers in PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− lung EC. The expression of ICAM-1, ICAM-2, VCAM-1, VEGFR1, and VEGFR2 was determined by FACS analysis using specific antibodies. Shaded areas show control IgG staining. The geometric mean values are shown in the bottom corner of each graph. B: production of VEGF in PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− lung EC. Level of VEGF was determined using an ELISA method. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). OD450, 450-nm optical density. *P < 0.05.

PEDF−/− lung EC are more migratory.

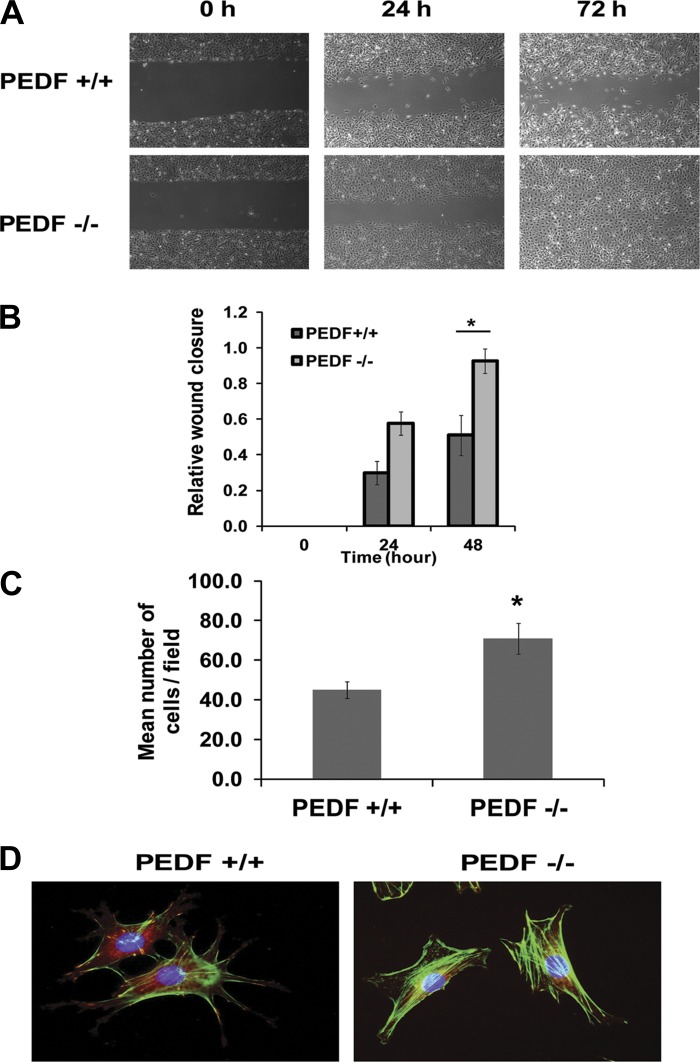

Migratory activity of EC is crucial during angiogenesis and generally suppressed in the presence of endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis, including PEDF. We next asked whether lack of PEDF impacts the migration of EC. Confluent monolayers of PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC were wounded, and wound closure was monitored over time. A significant wound closure was observed in PEDF−/− EC after 72 h, whereas wounds in PEDF+/+ EC were not completely closed (Fig. 3A). The quantification of wound closure is shown in Fig. 3B. Similar results were observed in Transwell migration assays (Fig. 3C). The enhanced migratory activity of PEDF−/− EC was further confirmed by examining the organization of actin and focal adhesions. More actin stress fibers and fewer focal adhesions were visible in PEDF−/− EC compared with PEDF+/+ EC (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

The impact of PEDF deficiency on the migration and formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions in lung EC. A: cell migration was determined by scratch wounding of a lung EC monolayer, and wound closure was monitored by photography. A representative experiment is shown. B: the quantitative assessment of the data in A. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05. C: Transwell migration of lung EC. Please note that the PEDF−/− lung EC were significantly more migratory compared with PEDF+/+ cells. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05. D: examination of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions in lung EC. Lung EC were stained with anti-vinculin, phalloidin, and DAPI (×630). Please note reduced number of focal adhesions and increased actin stress fibers in PEDF−/− EC.

PEDF−/− EC grow at a slower rate.

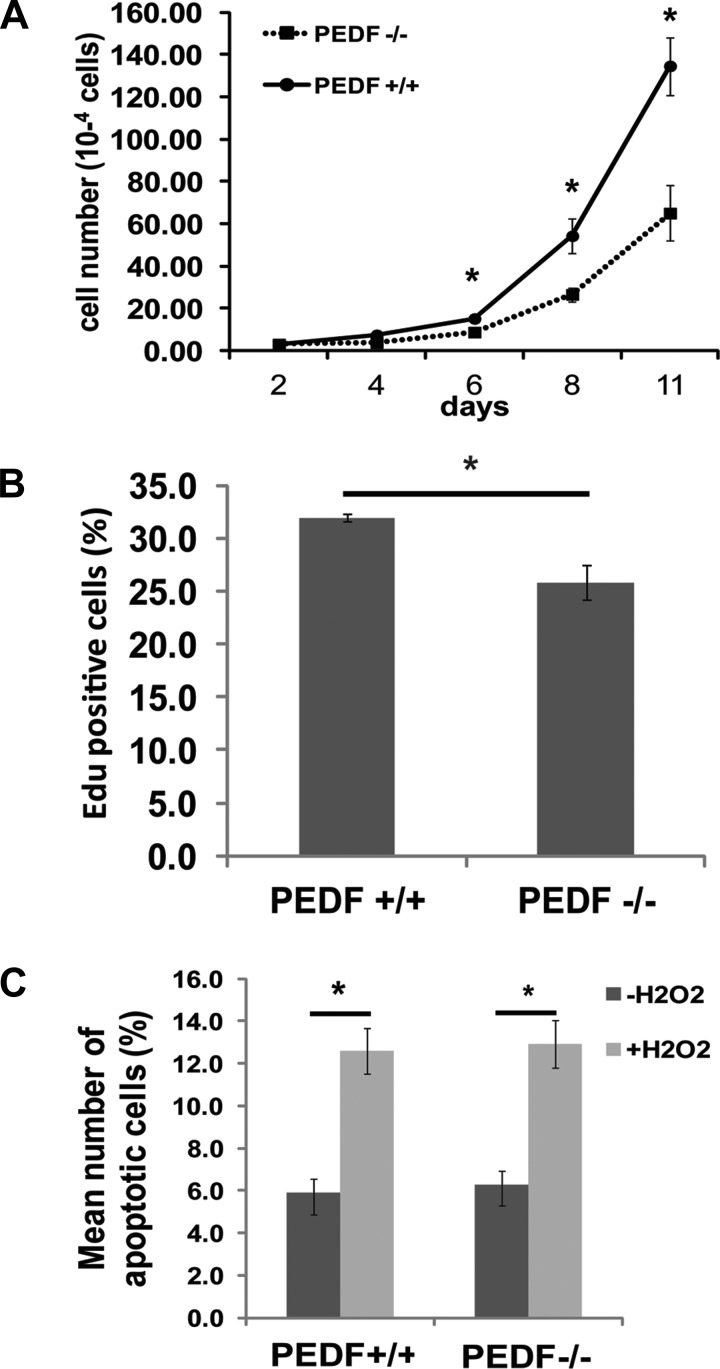

The impact of PEDF deficiency on proliferation of EC was determined by counting the number of cells for 2 wk. Figure 4A shows a significant decrease in the growth of PEDF−/− EC compared with PEDF+/+ EC. To examine whether the decreased growth in PEDF−/− EC was due to a decrease in the rate of DNA synthesis, the percentage of cells undergoing active DNA synthesis was determined by measuring the percentage of EdU-positive cells by FACS analysis. PEDF−/− EC showed decreased rate of DNA synthesis compared with PEDF+/+ EC (Fig. 4B). The effect of PEDF deficiency on apoptosis of EC was also examined by TUNEL assay. PEDF−/− EC exhibited a similar level of apoptosis compared with PEDF+/+ EC. When EC were challenged with H2O2, there was no significant difference in apoptosis rate between the two cell types (Fig. 4C). Similar results were also observed by examining the level of cleaved caspase-3 (not shown).

Fig. 4.

The effect of PEDF deficiency on proliferation and apoptosis of lung EC. A and B: the rate of EC proliferation was determined by counting the number of cells in triplicates after different days in culture (A) and by analyzing the rate of DNA synthesis by FACScan flow cytometer analysis (A and B). EdU, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine. C: the rate of apoptosis was determined by TdT-dUTP terminal nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining. Positive cells were counted using a fluorescence microscope and calculated as percentage of total cell number per field. As an apoptotic stimulus, H2O2 in EC growth medium was added for 24 h. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

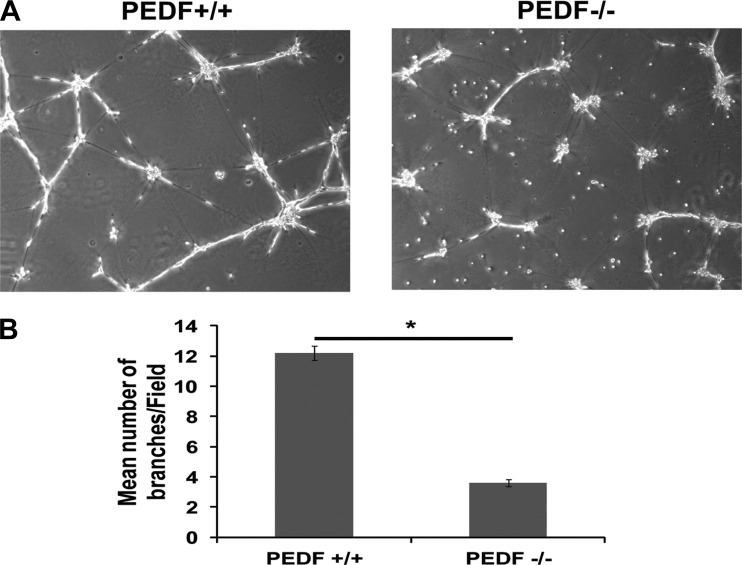

Attenuation of capillary morphogenesis in PEDF−/− lung EC.

EC undergo capillary morphogenesis when plated in Matrigel, which is a crucial feature of angiogenesis. PEDF+/+ EC exhibited well-organized capillary-like networks in Matrigel, whereas PEDF−/− EC failed to undergo capillary morphogenesis (Fig. 5A). The quantification of the data is shown in Fig. 5B. We next determined the effect of PEDF reexpression in PEDF−/− EC capillary morphogenesis. Reexpression of PEDF in PEDF−/− EC restored their ability to undergo capillary morphogenesis (Fig. 6A). The quantification of the data is shown in Fig. 6B.

Fig. 5.

PEDF−/− lung EC fail to undergo capillary morphogenesis. A: PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− lung EC were plated in Matrigel and photographed in digital format. B: the quantitative assessment of the data. Values are the mean number of branch points from 5 high-power fields (×100) ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05.

Fig. 6.

Reexpression of PEDF restored capillary morphogenesis of PEDF−/− EC. A: PEDF+/+ EC were infected with lenti viruses (LV) encoding vector control, and PEDF−/− EC were infected with LV encoding vector control or PEDF at a multiplicity of infection of 20 (LV 20) or 40 (LV 40) for the reexpression of PEDF. The next day, medium was removed, and cells were fed with fresh medium. After 72 h, cells were plated in Matrigel and photographed in digital format. B: the quantitative assessment of the data. Data are the mean number of branch points from 5 high-power fields (×100) ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05.

PEDF−/− EC are more adherent.

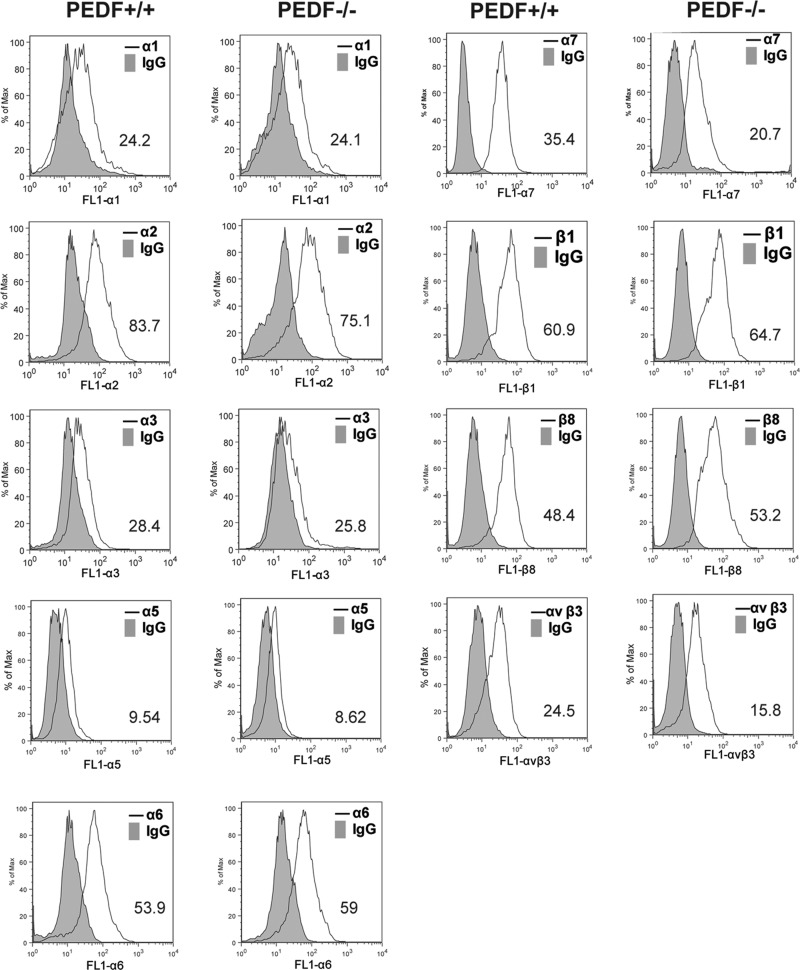

Alterations in migration of PEDF−/− EC implied that the deficiency in PEDF may affect adhesion of EC. We next investigated adhesion of PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC to various ECM proteins, including collagen I, collagen IV, fibronectin, and vitronectin. PEDF−/− EC adhered more strongly to collagen IV, fibronectin, and vitronectin compared with PEDF+/+ EC. Neither PEDF+/+ nor PEDF−/− cells adhered to collagen I (Fig. 7). Thus PEDF deficiency had a significant impact on interaction of lung EC with various ECM proteins. These results suggested that lack of PEDF may affect expression levels and/or activity levels of various cell surface integrins involved in adhesion and migration. Expression levels of various integrins were determined by FACScan analysis (Fig. 8). PEDF−/− EC expressed decreased levels of α3-, α7-, and αvβ3-integrins. PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC expressed similar levels of α1-, α2-, α5-, α6-, β1-, and β8-integrins. The mean fluorescence intensities are shown in each panel.

Fig. 7.

PEDF−/− lung EC exhibited enhanced adhesion to various extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. Adhesion of lung EC to collagen I (A), collagen IV (B), fibronectin (FN; C), and vitronectin (D) was determined by measuring number of adherent cells in each well coated with various concentration of ECM proteins. Number of adherent cells was quantified by measuring the cellular phosphatase activity as described in materials and methods. Values are means ± SE.

Fig. 8.

Expression of integrins in retinal EC. α1-, α2-, α3-, α5-, α6-, α7-, β1-, β8-, and αvβ3-integrin expression on lung EC was determined by FACS analysis. The geometric mean values are shown at the bottom corner of each graph. Similar results were observed using another isolation of EC.

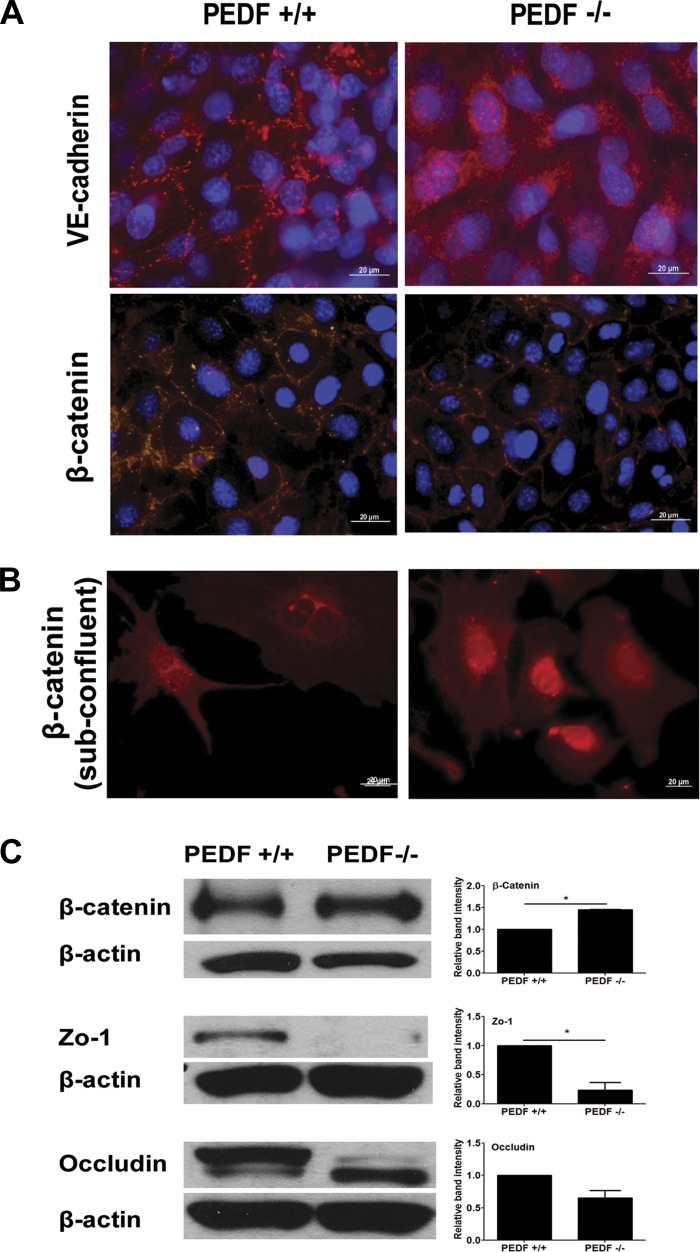

Localization of VE-cadherin and β-catenin.

VE-cadherin is a major component of the vascular EC adherens junctions and has a pivotal role in maintaining the integrity of vascular wall (19). VE-cadherin localized at sites of cell-cell contacts in PEDF+/+ EC as expected. However, VE-cadherin exhibited a diffused localization over the whole surface of PEDF−/− EC (Fig. 9A). The localization of β-catenin was also examined by immunofluorescence staining in confluent and subconfluent cells. In confluent cells, PEDF+/+ EC showed more punctate staining pattern compared with PEDF−/− EC. PEDF−/− EC exhibited more intact staining pattern at junction area (Fig. 9A). In subconfluent cells, PEDF−/− EC exhibited an increase in the level of β-catenin localized in the nucleus. However, a strong nuclear localization of β-catenin was not observed in PEDF+/+ EC (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Cellular localizations of VE-cadherin and β-catenin in confluent cells (A) and β-catenin in subconfluent cells (B) were determined. PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− lung EC were grown on FN-coated chamber slides and stained with specific antibodies and DAPI, as outlined in materials and methods. Scale bar indicates 20 μm. C: expression levels of β-catenin, zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), and occludin in confluent cells were determined by Western blot analysis. The β-actin was used for loading control. Relative band intensity was measured for quantification. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

The expression of ZO-1, occluding, and β-catenin was also determined by Western blot analysis of total cell lysates. Cell lysates were prepared from confluent cells for examining ZO-1, occluding, and β-catenin levels. PEDF−/− EC exhibited a lower level of ZO-1 compared with PEDF+/+ EC. Although occludin levels were similar in PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC, the size of the protein was different, suggesting changes in phosphorylation state. The total level of β-catenin was increased in PEDF−/− EC compared with PEDF+/+ EC (Fig. 9C). The increased expression and nuclear localization of β-catenin in PEDF−/− EC is consistent with activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in the absence of PEDF, as previously suggested (31).

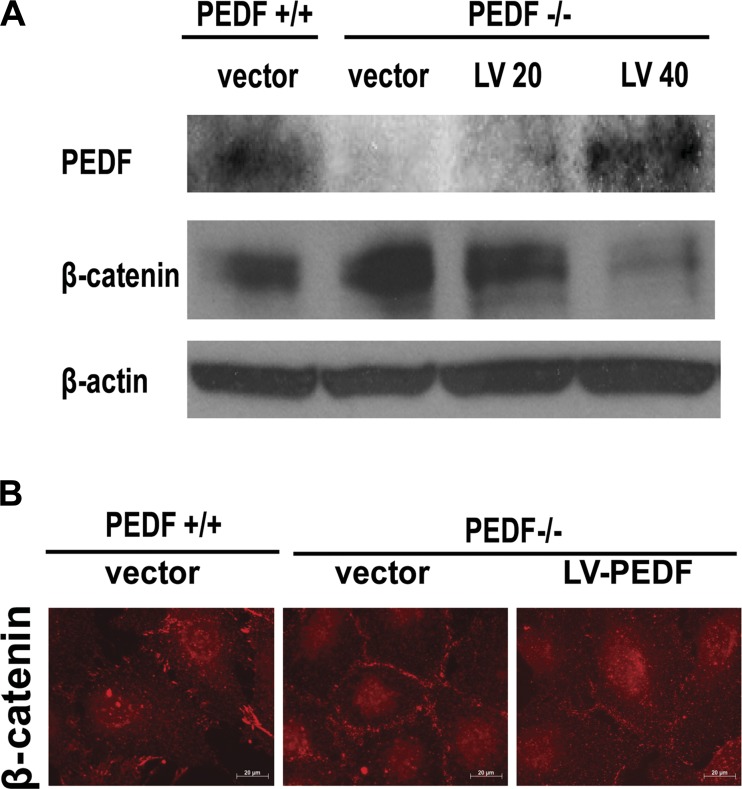

We next determined the effect of PEDF reexpression in PEDF−/− EC. When PEDF was reexpressed in PEDF−/− EC, the expression of β-catenin was suppressed (Fig. 10A) compared with PEDF−/− EC transduced with vector control. In addition, junctional localization of β-catenin was similar to PEDF+/+ EC, exhibiting less intact, more punctate pattern, compared with PEDF−/− EC transduced with vector control (Fig. 10B). Thus PEDF expression has a significant impact on β-catenin expression and localization.

Fig. 10.

PEDF reexpression restored expression and localization of β-catenin in PEDF−/− EC. A: PEDF and β-catenin levels were determined by Western blot analysis. PEDF+/+ EC were infected with LV encoding vector control, and PEDF−/− EC were infected with LV encoding vector control or PEDF at a multiplicity of infection of 20 or 40. The β-actin was used for loading control. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results. B: cellular localization of β-catenin in PEDF+/+ EC transfected with vector control, and PEDF−/− EC transfected with controls or PEDF. Scale bar indicates 20 μm.

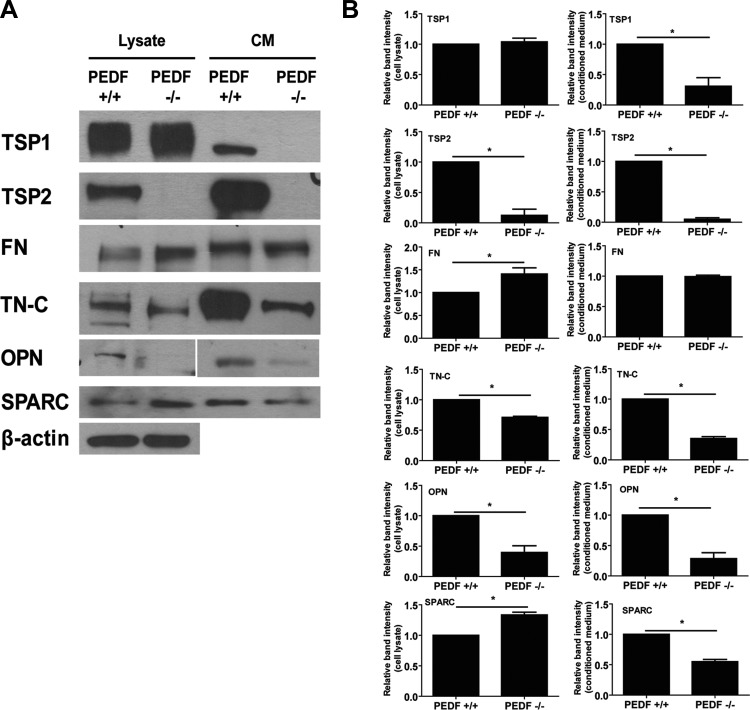

Altered production of ECM proteins in PEDF−/− EC.

The PEDF deficiency-mediated EC defects may be related to alteration of the synthesis and interaction with ECM proteins. TSP1 is a member of the TSP family of matricellular proteins with potent antiangiogenic and inflammatory activity (35). PEDF−/− EC expressed slightly more TSP1 in their lysate. However, secreted TSP1 in CM collected from PEDF−/− EC was not detectable, whereas PEDF+/+ EC secreted significant amounts (Fig. 11). TSP2 is also antiangiogenic and is closely related to TSP1. PEDF−/− EC did not express detectable levels of TSP2 in their lysates or CM (Fig. 11). We also determined the expression of other ECM proteins, including fibronectin, tenascin-C, osteopontin, and SPARC. PEDF−/− EC produced more cell-associated fibronectin than PEDF+/+ EC. However, both cell types exhibited similar level of secreted fibronectin in CM. Tenascin-C and osteopontin levels decreased in PEDF−/− EC compared with PEDF+/+ cells. Although PEDF−/− EC expressed more cell-associated SPARC than PEDF+/+ EC, the level of SPARC in CM of PEDF−/− EC was lower. Thus overall level of SPARC was not altered by PEDF deficiency (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Altered production of ECM proteins in PEDF−/− EC. A: level of ECM proteins in PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− lung EC was determined by Western blot analysis. The CM and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for thrombospondin-1 (TSP1), TSP2, FN, tenascin-C (TN-C), osteopontin (OPN), and SPARC using specific antibodies. The β-actin was used for loading control. B: quantifications are shown using relative band intensities. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

PEDF deficiency impacts expression of NO synthase and NO production.

NO is a major player in VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, and eNOS is the major source of NO production in the endothelium. Inhibition of eNOS activity attenuates capillary morphogenesis in vitro and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis in vivo (26, 39). Although iNOS is more efficient in NO production, it is generally associated with inflammatory conditions, and it is recognized as a marker of inflammation. We determined the expression and phosphorylation of eNOS in PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− EC by Western blot analysis. Both cell types expressed similar level of total eNOS. However, phosphorylation of eNOS was significantly decreased in PEDF−/− EC compared with PEDF+/+ EC (Fig. 12A). In contrast, the levels of iNOS and nNOS were dramatically increased in PEDF−/− EC (Fig. 12A), which corresponded to a twofold increase in NO level compared with PEDF+/+ EC (Fig. 12B).

Fig. 12.

Alterations in the expression of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) in PEDF−/− lung EC. A: phospho-endothelial NOS (p-eNOS), total eNOS, inducible NOS (iNOS), and neuronal NOS (nNOS) in cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. Phosphorylation of eNOS was attenuated in PEDF−/− lung EC. Expression level of iNOS and nNOS was increased in PEDF−/− lung EC. The β-actin was used for loading control. These experiments were repeated using two different isolations of EC with similar results. B: intracellular nitric oxide (NO) level in lung EC was measured using 4-amino-5-methylamino-2',7'-difluorofluorescein diacetate (DAF-FM). Please note a significant increase in intracellular NO level in PEDF−/− lung EC compared with PEDF+/+ lung EC. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

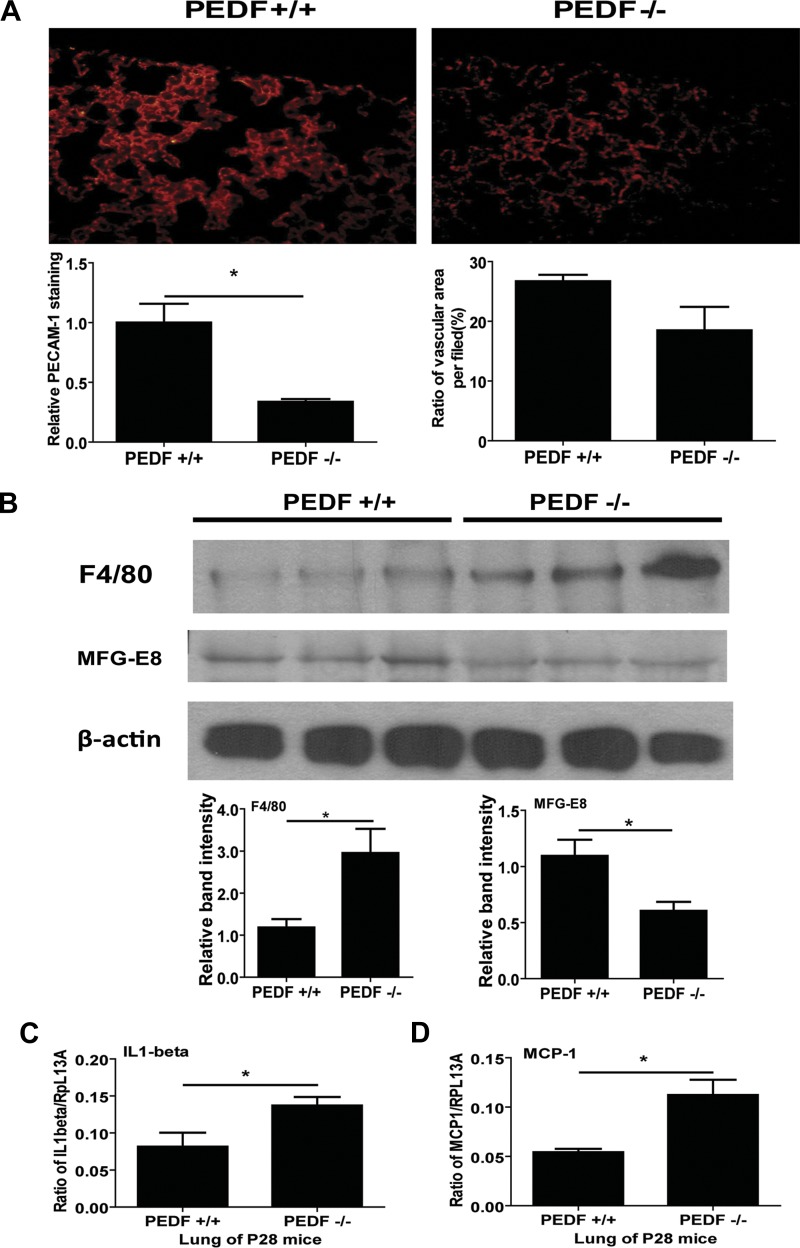

Decreased PECAM-1 expression and enhanced expression of inflammatory markers in the lung of PEDF−/− mice.

We examined PECAM-1 expression in lung sections prepared form PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice by immunofluorescence staining.

In PEDF−/− lungs, a lower intensity of PECAM-1 staining was detected, consistent with decreased PECAM-1 expression in PEDF−/− lung EC. However, the ratio of vascular area in the lung of PEDF−/− mice was not significantly lower than in the lung of PEDF+/+ mice (Fig. 13A). Monoclonal antibody for F4/80 was used to detect the cell surface glycoprotein marker of macrophages to access the inflammation status of lungs from PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice (32, 33). In the lung of PEDF−/− mice, expression level of F4/80 was significantly elevated compared with that of PEDF+/+ mice.

Fig. 13.

A: lung sections from postnatal day 28 (P28) PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice were stained with anti-PECAM-1, and fluorescence images were obtained in digital format (×400). Vascular PECAM-1 intensity in lung from PEDF−/− mice was lower compared with lungs from PEDF+/+ mice. Values are means ± SE (n = 4). *P < 0.05. These results were consistent with reduced PECAM-1 levels detected in PEDF−/− lung EC. Vascular areas in lung from PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− were not significantly different. B: expression level of F4/80 and milk fat globule epidermal growth factor-8 (MFG-E8) was determined by Western blot analysis of lung lysates prepared from P28 PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice. β-Actin was used for loading control. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05. C and D: mRNA expressions of inflammatory cytokines in lung of P28 PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice were investigated by quantitative real-time PCR method. Interleukin (IL)-1β (C) and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 (D) levels are shown. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05. Please note increased expression of these cytokines in the lungs from PEDF−/− mice.

We also examined the expression of MFG-E8 in lungs from PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice. In lungs of mice with acute lung injury, MFG-E8 level is decreased, and exogenous treatment with recombinant MFG-E8 alleviates acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) instillation (2). Expression of MFG-E8 was also decreased in PEDF−/− mice compared with PEDF+/+ mice (Fig. 13B). To further determine the inflammation status of lungs from PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice, mRNA levels of MCP-1 and IL-1β were also accessed by quantitative real-time PCR. The levels of IL-1β (Fig. 13C) and MCP-1 (Fig. 13D) were significantly increased in the lungs from PEDF−/− mice compared with PEDF+/+ mice.

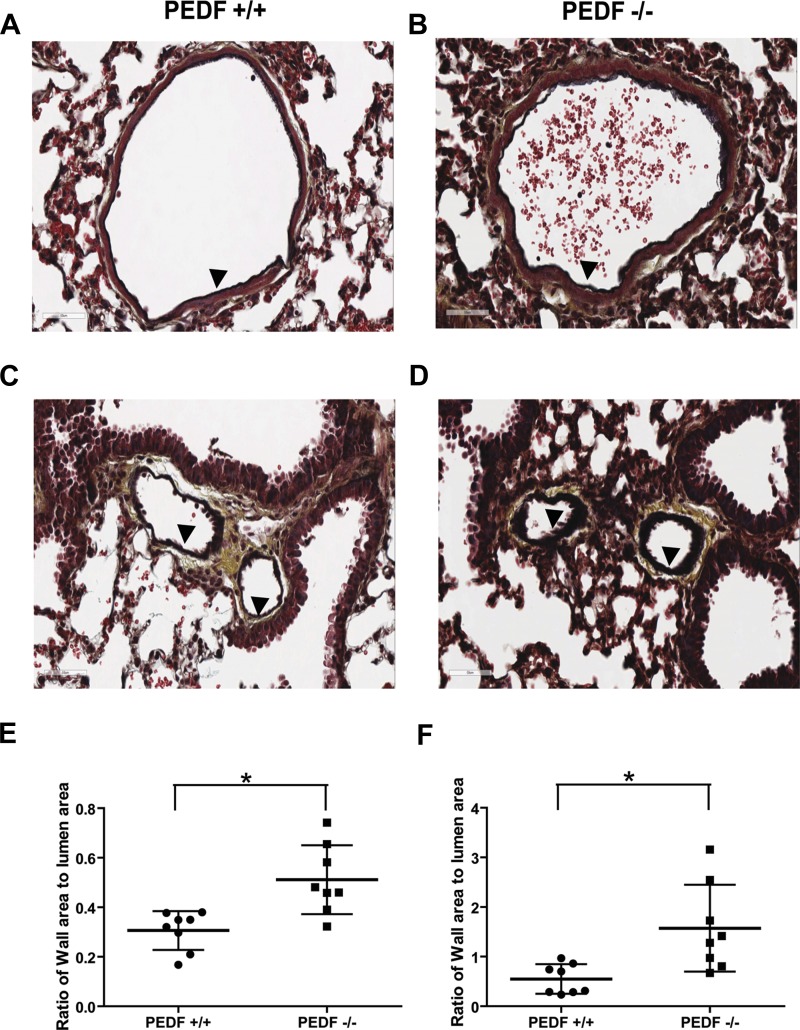

The morphology of arterioles and venules in lung tissue were examined in sections stained by movat pentachrome. The arteriole wall in PEDF−/− mice was thicker than in PEDF+/+ mice (Fig. 14, A and B). The similar result was also observed in venules (Fig. 14, C and D). The ratios of wall area to lumen area in vessels were quantified (Fig. 14, E and F). Vessel wall area in the lung of PEDF−/− mice was elevated compared with that in PEDF+/+ mice. However, the area of lumen in arterioles and venules was not significantly different in PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice (not shown).

Fig. 14.

Vascular abnormities in PEDF−/− lungs. Histological lung sections were prepared from P28 PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice and stained with pentachrome movat. Arterioles are shown in A and B. Venules are shown in C and D. A and C are sections from PEDF+/+ mice, and B and D are sections from PEDF−/− mice. Sections were obtained from comparable areas of lung tissue. Magnifications are ×400. Arrowheads indicate vessel wall in arterioles and venules. Ratio of vessel wall area to lumen area is shown in E (arteriole) and F (venules) (n = 8). *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Here we addressed the cell autonomous effects of PEDF in the development and function of lung endothelium using PEDF+/+ and PEDF−/− mice and lung EC prepared from these mice. We found PEDF−/− lung EC were more migratory, proliferated at a slower rate, failed to undergo capillary morphogenesis, adhered more strongly to ECM proteins, and exhibited altered junctional properties, along with a significant increase in β-catenin expression and nuclear localization. The PEDF−/− EC also produced increased levels of VEGF, altered ECM protein production, and expressed significantly higher levels of nNOS and iNOS with increased intracellular NO levels. In vivo, we observed decreased levels of PECAM-1 staining and increased levels of inflammatory cytokines including MCP-1 and IL-1β, and F4/80 a marker of inflammatory macrophages. The level of MFG-E8, a protein with anti-inflammatory activity, was also decreased in lungs of PEDF−/− mice. These observations were also consistent with increased thickness of blood vessel walls in lungs from PEDF−/− mice. Together our results support the proangiogenic and proinflammatory characteristics of lung endothelium in the absence of PEDF.

Expression of PEDF in lung endothelium has been studied to address the question of whether lung endothelium produces PEDF. In human lung biopsies, PEDF is expressed in lung alveolus, and its expression was colocalized with EC within microvessels (8). In contrast, PEDF was not included in the list of EC-enriched genes when expressed sequence tags obtained from lung EC fraction was analyzed to identify genes enriched in EC by Favre et al. (14). However, mRNA expression of PEDF was detected by real-time qPCR method in lung EC isolated from PEDF+/+ mice, and secreted PEDF was detected in CM collected from PEDF+/+ lung EC by Western blot analysis. Thus PEDF is expressed and secreted by lung EC.

Migration is fundamental to the ability of EC to form new blood vessels. The enhanced migration observed in PEDF−/− EC is consistent with the antiangiogenic activity of PEDF and increased levels of VEGF by PEDF−/− EC. The PEDF antimigratory effect of PEDF has been previously demonstrated in human bone marrow EC (4). Cell migration is also closely associated with the formation of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers. PEDF−/− EC also showed increased levels of actin stress fibers and reduced number of focal adhesions, consistent with their migratory phenotype (11, 29). The increased formation of actin stress fibers has been reported in rat microvascular lung EC after exposure to cigarette smoke to induce inflammation and human dermal microvascular EC incubated with inflammatory cytokines (32, 34). Thus the increased actin stress fiber formation in PEDF−/− lung EC are consistent with the anti-inflammatory activity of PEDF, and its deficiency may be conducive to production of inflammatory mediators.

We observed a fourfold increase in the amount of VEGF produced by PEDF−/− lung EC compared with PEDF+/+ lung EC. In addition, expression of VCAM-1, another marker of inflammation, was also increased in PEDF−/− lung EC. Others have shown that exposure of mice to LPS results in inflammation and increased expression of VEGF in the lung (20). Furthermore, VCAM-1 expression is increased in LPS-treated mouse lung EC compared with nontreated cells (28). Thus PEDF deficiency in the lung endothelium may promote the progression of inflammation.

In lungs, iNOS has been known for its crucial role during inflammation. iNOS is upregulated by various inflammatory mediators, including tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon-γ, and LPS. NO level is increased by upregulation of iNOS expression in various inflammatory lung diseases, including bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The lung iNOS is considered the major NO-producing source in inflammatory pathways (38). In human retinal pericytes, PEDF attenuates iNOS expression and NO production induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein (50). In this study, the expression of iNOS and NO levels was significantly increased in PEDF−/− lung EC. Taken together, PEDF may mediate its anti-inflammatory activity in the lung by regulating expression level of iNOS, perhaps through the attenuation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway, decreasing iNOS expression.

PEDF inhibits canonical Wnt signaling through interaction with LRP6 receptor and regulates production of proangiogenic and proinflammatory factors, including VEGF (31). Activation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway is followed by the nuclear translocation of β-catenin, which drives the expression of target genes (6). We observed a significant increase in nuclear localization of β-catenin in PEDF−/− lung EC. In addition, the expression of iNOS is regulated by Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in hepatocytes and some cancer cells (13). Thus our results suggest that upregulation of iNOS and VEGF in PEDF−/− lung EC results from the activation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway, as previously demonstrated for another member of the serine protease inhibitor family (31).

PEDF is also known as contact inhibitory factor for its ability to arrest growth when cells reach confluence. Incubation of human umbilical vein EC with PEDF antibody enhanced their proliferation (25). However, PEDF−/− EC exhibited slower proliferation and DNA synthesis compared with PEDF+/+ EC. When iNOS is overexpressed in human coronary artery smooth muscle cell and human umbilical vein EC, their proliferation is decreased (7). In addition, iNOS-mediated NO overproduction results in inhibition of DNA synthesis (42). Therefore, the increased expression of iNOS and production of NO may also be attributed to the attenuation of DNA synthesis and proliferation of PEDF−/− EC.

The PEDF−/− lung EC were more adherent on collagen IV, fibronectin, and vitronectin. The alteration in adhesive properties of PEDF−/− lung EC may be contributed, at least in part, to decreased expression of tenascin-C. Tenascin-C has antiadhesive activity through binding of the FN type III repeat and interfere with cell binding to fibronectin (44). Osteopontin also has antiadhesive activity. In endothelial progenitor cells, osteopontin decreases cell adhesion (47). Thus decreased production of tenascin-C and osteopontin may contribute to altered cell adhesion properties of PEDF−/− EC. TSP1 and TSP2 are also ECM proteins with important roles in angiogenesis and inflammation. They have similar structural domains and exhibit antiangiogenic activity (16), but their expression is differentially regulated during angiogenesis (24). Here, expression of TSP2 was dramatically downregulated in PEDF−/− EC. A decrease in secreted level of TSP1 was also observed in PEDF−/− EC, despite similar expression of cell-associated TSP1. Thus PEDF deficiency had a modest effect on the expression of TSP1, but completely suppressed TSP2 expression. These results imply that PEDF is involved in the regulation of TSP expression and perhaps their posttranslational processing (27).

F4/80 is a cell surface glycoprotein on the macrophages, and elevation of its level in the tissue suggests enhanced recruitment of macrophages (33). Lungs from PEDF−/− mice exhibited a proinflammatory phenotype revealed by a significant increase in the level of F4/80 antigen. In addition, the level of MFG-E8 was decreased in the lungs from PEDF−/− mice. MFG-E8 is a secreted molecule involved in the clearance of apoptotic cells, along with anti-inflammatory activity, especially in the lung (9). After acute lung injury is induced by LPS instillation in mice, MFG-E8 mRNA and protein levels were attenuated in the lung (2). These results suggest that lack of PEDF may be associated with the proinflammatory state of the lung in PEDF−/− mice. PEDF may inhibit inflammation by suppressing macrophage activation and ameliorates macrophage recruitment by inhibiting MCP-1 expression (48, 49). These results are consistent with our finding and a regulatory role for PEDF in lung inflammation.

Inflammation in the lung results in remodeling of the vascular structure. When inflammation is induced in the lung by infection, vessel wall thickness increases (18). We observed a significant increase in the vessel wall thickness of the lungs from PEDF−/− mice. These results further support an important role for PEDF in modulation of the inflammatory state of the lung. These results in lung are also consistent with those previously reported in the pancreas of PEDF−/− mice (12).

In summary, our studies demonstrated that lack of PEDF promotes the migratory activity of lung of EC consistent with the proposed PEDF antiangiogenic activity. Furthermore, the absence of PEDF in EC was associated with the onset of an inflammatory phenotype. Lack of PEDF contributed to elevation of VEGF, iNOS, and VCAM-1 levels in EC. The absence of PEDF also impacted the proliferation, adhesion, and capillary morphogenesis of EC. These were concomitant with significant changes in the ECM proteins produced by EC, and activation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway. In vivo, PEDF deficiency was associated with an increase in vessel wall thickness and onset of inflammatory phenotypes in the lung. Together these results demonstrate an important role for PEDF expression in regulation of the proangiogenic and proinflammatory phenotype of the lung endothelium.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants R01 EY-016995, RC4 EY-021357, P30EY-016665, R21 EY-023024, and P30 CA-014520 University of Wisconsin (UW) Paul P. Carbone Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Institutes of Health and an unrestricted departmental award from Research to Prevent Blindness. N. Sheibani is a recipient of a Research Award from American Diabetes Association, 1–10-BS-160, and Retina Research Foundation. E. S. Shin is supported by a UW-Madison UW-Milwaukee Inter Campus grant and predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association, 12PRE12030099.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: E.S.S., C.M.S., and N.S. conception and design of research; E.S.S. and C.M.S. performed experiments; E.S.S., C.M.S., and N.S. analyzed data; E.S.S., C.M.S., and N.S. interpreted results of experiments; E.S.S. prepared figures; E.S.S. drafted manuscript; E.S.S., C.M.S., and N.S. edited and revised manuscript; E.S.S., C.M.S., and N.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Stan Wiegand from Regeneron for providing us with the PEDF null mice. We also thank Dr. SunYoung Park for assistance with VEGF determinations.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahn JK, Moon HJ. Changes in aqueous vascular endothelial growth factor and pigment epithelium-derived factor after ranibizumab alone or combined with verteporfin for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 148: 718–724, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aziz M, Matsuda A, Yang WL, Jacob A, Wang P. Milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor-factor 8 attenuates neutrophil infiltration in acute lung injury via modulation of CXCR2. J Immunol 189: 393–402, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Becerra SP, Sagasti A, Spinella P, Notario V. Pigment epithelium-derived factor behaves like a noninhibitory serpin. Neurotrophic activity does not require the serpin reactive loop. J Biol Chem 270: 25992–25999, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bernard A, Gao-Li J, Franco CA, Bouceba T, Huet A, Li Z. Laminin receptor involvement in the anti-angiogenic activity of pigment epithelium-derived factor. J Biol Chem 284: 10480–10490, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen L, Zhang SSM, Barnstable CJ, Tombran-Tink J. PEDF induces apoptosis in human endothelial cells by activating p38 MAP kinase dependent cleavage of multiple caspases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 348: 1288–1295, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 149: 1192–1205, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cooney R, Hynes SO, Duffy AM, Sharif F, O'Brien T. Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer of nitric oxide synthase isoforms and vascular cell proliferation. J Vasc Res 43: 462–472, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cosgrove GP, Brown KK, Schiemann WP, Serls AE, Parr JE, Geraci MW, Schwarz MI, Cool CD, Worthen GS. Pigment epithelium-derived factor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170: 242–251, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cui T, Miksa M, Wu R, Komura H, Zhou M, Dong W, Wang Z, Higuchi S, Chaung W, Blau SA, Marini CP, Ravikumar TS, Wang P. Milk fat globule epidermal growth factor 8 attenuates acute lung injury in mice after intestinal ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181: 238–246, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dawson DW, Volpert OV, Gillis P, Crawford SE, Xu H, Benedict W, Bouck NP. Pigment epithelium-derived factor: a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Science 285: 245–248, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Devallière J, Chatelais M, Fitau J, Gérard N, Hulin P, Velazquez L, Turner CE, Charreau B. LNK (SH2B3) is a key regulator of integrin signaling in endothelial cells and targets α-parvin to control cell adhesion and migration. FASEB J 26: 2592–2606, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Doll JA, Stellmach VM, Bouck NP, Bergh AR, Lee C, Abramson LP, Cornwell ML, Pins MR, Borensztajn J, Crawford SE. Pigment epithelium-derived factor regulates the vasculature and mass of the prostate and pancreas. Nat Med 9: 774–780, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Du Q, Park KS, Guo Z, He P, Nagashima M, Shao L, Sahai R, Geller DA, Hussain SP. Regulation of human nitric oxide synthase 2 expression by Wnt beta-catenin signaling. Cancer Res 66: 7024–7031, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Favre CJ, Mancuso M, Maas K, McLean JW, Baluk P, McDonald DM. Expression of genes involved in vascular development and angiogenesis in endothelial cells of adult lung. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1917–H1938, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Han RNN, Stewart DJ. Defective lung vascular development in endothelial nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. Trends Cardiovasc Med 16: 29–34, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hiscott P, Paraoan L, Choudhary A, Ordonez JL, Al-Khaier A, Armstrong DJ. Thrombospondin 1, thrombospondin 2 and the eye. Prog Retin Eye Res 25: 1–18, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holderfield MT, Hughes CCW. Crosstalk between vascular endothelial growth factor, notch, and transforming growth factor-β in vascular morphogenesis. Circ Res 102: 637–652, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hopkins N, Cadogan E, Giles S, McLoughlin P. Chronic airway infection leads to angiogenesis in the pulmonary circulation. J Appl Physiol 91: 919–928, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Julie G. Breaking the VE-cadherin bonds. FEBS Lett 583: 1–6, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karmpaliotis D, Kosmidou I, Ingenito EP, Hong K, Malhotra A, Sunday ME, Haley KJ. Angiogenic growth factors in the pathophysiology of a murine model of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L585–L595, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kasahara Y, Tuder RM, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Le Cras TD, Abman S, Hirth PK, Waltenberger J, Voelkel NF. Inhibition of VEGF receptors causes lung cell apoptosis and emphysema. J Clin Invest 106: 1311–1319, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kawaguchi T, Yamagishi S, Itou M, Okuda K, Sumie S, Kuromatsu R, Sakata M, Abe M, Taniguchi E, Koga H, Harada M, Ueno T, Sata M. Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits lysosomal degradation of Bcl-xL and apoptosis in HepG2 cells. Am J Pathol 176: 168–176, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee CG, Ma B, Takyar S, Ahangari F, DelaCruz C, He CH, Elias JA. Studies of vascular endothelial growth factor in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 8: 512–515, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin Tn Kim GM, Chen JJ, Cheung WM, He YY, Hsu CY. Differential regulation of thrombospondin-1 and thrombospondin-2 after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Stroke 34: 177–186, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matsumoto K, Ishikawa H, Nishimura D, Hamasaki K, Nakao K, Eguchi K. Antiangiogenic property of pigment epithelium-derived factor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 40: 252–259, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morais C, Ebrahem Q, Anand-Apte B, Parat MO. Altered angiogenesis in caveolin-1 gene-deficient mice is restored by ablation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am J Pathol 180: 1702–1714, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nita-Lazar A, Haltiwanger RS. Methods for analysis of O-linked modifications on epidermal growth factor-like and thrombospondin type 1 repeats. In: Methods in Enzymology, edited by Minoru F. New York: Academic, 2006, p. 93–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O'Dea KP, Dokpesi JO, Tatham KC, Wilson MR, Takata M. Regulation of monocyte subset proinflammatory responses within the lung microvasculature by the p38 MAPK/MK2 pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L812–L821, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oviedo PJ, Sobrino A, Laguna-Fernandez A, Novella S, Tarín JJ, García-Pérez MA, Sanchís J, Cano A, Hermenegildo C. Estradiol induces endothelial cell migration and proliferation through estrogen receptor-enhanced RhoA/ROCK pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol 335: 96–103, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Park K, Jin J, Hu Y, Zhou K, Ma JX. Overexpression of pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits retinal inflammation and neovascularization. Am J Pathol 178: 688–698, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Park K, Lee K, Zhang B, Zhou T, He X, Gao G, Murray AR, Ma JX. Identification of a novel inhibitor of the canonical Wnt pathway. Mol Cell Biol 31: 3038–3051, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Qiao J, Huang F, Naikawadi RP, Kim KS, Said T, Lum H. Lysophosphatidylcholine impairs endothelial barrier function through the G protein-coupled receptor GPR4. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L91–L101, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Savale L, Tu L, Rideau D, Izziki M, Maitre B, Adnot S, Eddahibi S. Impact of interleukin-6 on hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and lung inflammation in mice. Respir Res 10: 6, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schweitzer KS, Hatoum H, Brown MB, Gupta M, Justice MJ, Beteck B, Van Demark M, Gu Y, Presson RG, Jr, Hubbard WC, Petrache I. Mechanisms of lung endothelial barrier disruption induced by cigarette smoke: role of oxidative stress and ceramides. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L836–L846, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sheibani N, Frazier WA. Thrombospondin-1, PECAM-1, and regulation of angiogenesis. Histol Histopathol 14: 285–294, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Steele FR, Chader GJ, Johnson LV, Tombran-Tink J. Pigment epithelium-derived factor: neurotrophic activity and identification as a member of the serine protease inhibitor gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90: 1526–1530, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Su X, Sorenson CM, Sheibani N. Isolation and characterization of murine retinal endothelial cells. Mol Vis 9: 171–178, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sugiura H, Ichinose M. Nitrative stress in inflammatory lung diseases. Nitric Oxide 25: 138–144, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tang Y, Scheef EA, Gurel Z, Sorenson CM, Jefcoate CR, Sheibani N. CYP1B1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase combine to sustain proangiogenic functions of endothelial cells under hyperoxic stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 298: C665–C678, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tombran-Tink J, Barnstable CJ. PEDF: a multifaceted neurotrophic factor. Nat Rev Neurosci 4: 628–636, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tombran-Tink J, Chader GG, Johnson LV. PEDF: a pigment epithelium-derived factor with potent neuronal differentiative activity. Exp Eye Res 53: 411–414, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tomko RJ, Jr, Azang-Njaah NN, Lazo JS. Nitrosative stress suppresses checkpoint activation after DNA synthesis inhibition. Cell Cycle 8: 299–305, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ueda S, Yamagishi S, Matsui T, Jinnouchi Y, Imaizumi T. Administration of pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits left ventricular remodeling and improves cardiac function in rats with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Pathol 178: 591–598, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Van Obberghen-Schilling E, Tucker RP, Saupe F, Gasser I, Cseh B, Orend G. Fibronectin and tenascin-C: accomplices in vascular morphogenesis during development and tumor growth. Int J Dev Biol 55: 511–525, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang JJ, Zhang SX, Mott R, Chen Y, Knapp RR, Cao W, Ma JX. Anti-inflammatory effects of pigment epithelium-derived factor in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1166–F1173, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang S, Gottlieb JL, Sorenson CM, Sheibani N. Modulation of thrombospondin 1 and pigment epithelium-derived factor levels in vitreous fluid of patients with diabetes. Arch Ophthalmol 127: 507–513, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yu M, Liu Q, Yi K, Wu L, Tan X. Effects of osteopontin on functional activity of late endothelial progenitor cells. J Cell Biochem 112: 1730–1736, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zamiri P, Masli S, Streilein JW, Taylor AW. Pigment epithelial growth factor suppresses inflammation by modulating macrophage activation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 3912–3918, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang SX, Wang JJ, Dashti A, Wilson K, Zou MH, Szweda L, Ma JX, Lyons TJ. Pigment epithelium-derived factor mitigates inflammation and oxidative stress in retinal pericytes exposed to oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J Mol Endocrinol 41: 135–143, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang SX, Wang JJ, Dashti A, Wilson K, Zou MH, Szweda L, Ma JX, Lyons TJ. Pigment epithelium-derived factor mitigates inflammation and oxidative stress in retinal pericytes exposed to oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J Mol Endocrinol 41: 135–143, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ziehr J, Sheibani N, Sorenson CM. Alterations in cell-adhesive and migratory properties of proximal tubule and collecting duct cells from bcl-2−/− mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F1154–F1163, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zudaire E, Gambardella L, Kurcz C, Vermeren S. A computational tool for quantitative analysis of vascular networks. PLos One 6: e27385, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]