Abstract

Obesity associated with metabolic derangements (ObM) worsens the prognosis of patients with coronary artery stenosis (CAS), but the underlying cardiac pathophysiologic mechanisms remain elusive. We tested the hypothesis that ObM exacerbates cardiomyocyte loss distal to moderate CAS. Obesity-prone pigs were randomized to four groups (n = 6 each): lean-sham, ObM-sham, lean-CAS, and ObM-CAS. Lean and ObM pigs were maintained on a 12-wk standard or atherogenic diet, respectively, and left circumflex CAS was then induced by placing local-irritant coils. Cardiac structure, function, and myocardial oxygenation were assessed 4 wk later by computed-tomography and blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) MRI, the microcirculation with micro-computed-tomography, and injury mechanisms by immunoblotting and histology. ObM pigs showed obesity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance. The degree of CAS (range, 50–70%) was similar in lean and ObM pigs, and resting myocardial perfusion and global cardiac function remained unchanged. Increased angiogenesis distal to the moderate CAS observed in lean was attenuated in ObM pigs, which also showed microvascular dysfunction and increased inflammation (M1-macrophages, TNF-α expression), oxidative stress (gp91), hypoxia (BOLD-MRI), and fibrosis (Sirius-red and trichrome). Furthermore, lean-CAS showed increased myocardial autophagy, which was blunted in ObM pigs (downregulated expression of unc-51-like kinase-1 and autophagy-related gene-12; P < 0.05 vs. lean CAS) and associated with marked apoptosis. The interaction diet xstenosis synergistically inhibited angiogenic, autophagic, and fibrogenic activities. ObM exacerbates structural and functional myocardial injury distal to moderate CAS with preserved myocardial perfusion, possibly due to impaired cardiomyocyte turnover.

Keywords: autophagy, apoptosis, inflammation

the constellation of obesity-metabolic derangements (ObM) often accompanies insulin resistance (IR), hypertension, and atherogenic dyslipidemia and afflicts almost a quarter of the patient population with coronary artery disease (CAD) (8). ObM confers a worse prognosis in patients with CAD (8, 23, 25), yet the underlying cardiac pathophysiological mechanisms are ill defined. Clinically, ObM is associated with increased inducible myocardial ischemia among patients with subclinical atherosclerosis (35), possibly due to increased myocardial metabolic demands and/or decreased efficiency of glucose utilization. Indeed, obesity and IR, major components of ObM, increase free fatty acid (FFA) use and decrease cardiac efficiency (26), which may interfere with cardiac energy usage adaption during an ischemic insult, and thereby exacerbate myocardial injury.

Autophagy is a critical catabolic process that degrades dysfunctional organelles and cytoplasmic components, and recycles amino acids under starvation. This protective mechanism serves to ameliorate tissue injury by disposing of damaged cellular structures and can thereby limit cell death in chronically ischemic myocardium (36), a condition of insufficient oxygen and nutrition resembling starvation. In contrast, autophagy may be impaired in conditions associated with excessive nutrition availability like hypercholesterolemia (13) and obesity (37), which might conceivably blunt autophagy and interfere with myocardial adaptation to CAD. Given its stipulated impact on injurious cellular turnover mechanisms, ObM might interfere with myocardial remodeling, but its effect on myocardial adaptation to coronary artery stenosis (CAS) is incompletely understood.

Resting coronary blood flow is usually well preserved until a CAS exceeds 70% luminal area obstruction (33) and becomes hemodynamically significant, although microvascular functional reserve (response to challenge) might be attenuated during obstructions greater than 50%. Nevertheless, early adaptive alterations detectable distal to intermediate CAS, associated with relatively preserved structure and perfusion, might afford discerning subtle impairments in this process.

Therefore, this study aimed to test the hypothesis that ObM exacerbates myocardial structural and functional injury in intermediate CAS, in association with inhibited autophagy and augmented apoptosis. We studied both in vivo and ex vivo hearts of Ossabaw pigs, a unique large animal model that progressively develops ObM (10).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Littermate Ossabaw pigs (Swine Resource, Indiana University) were randomized to four groups (n = 6 each): lean-sham, ObM-sham, lean-CAS, and ObM-CAS. Lean and ObM pigs started at the age of 3 mo had 16 wk of standard chow or an atherogenic diet (5B4L; Purina Test Diet, Richmond, IN) (21), respectively. CAS was induced by local-irritant coils placed in the left circumflex (LCX) coronary artery after 12 wk of diet (6). To prevent mortality due to fibrillation or thrombosis, amiodarone (200 mg/day) and aspirin (325 mg/day), respectively, were given orally 2 days before stenting and for 14 days after. Four weeks later, fasting blood samples were collected, and the pigs studied with MRI (for myocardial oxygenation) followed by multidetector computed-tomography (MDCT; for cardiac structure, function, and myocardial perfusion) 2 days later. Three days after the in vivo studies, pigs were euthanized (100 mg/kg iv pentobarbital sodium; Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, IA), hearts were removed, and left ventricle (LV) tissue from the area-at-risk distal to the coil was immediately shock-frozen and stored at −80°C, preserved in formalin, or prepared for micro-CT studies. Myocardial autophagy, apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, microvascular architecture, and fibrosis were then assessed.

Systemic Measurements

Blood pressure and heart rate were measured with an intra-arterial catheter during MDCT studies; heart rate was also monitored during MRI. Rate-pressure product (RPP), an index of myocardial oxygen consumption (14), was calculated by heart rate × systolic blood pressure × 10−2. Circulating levels of the plasma renin activity (PRA), leptin, and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 were tested as previously described (12, 41), and total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides by standard procedures (Roche). Systemic oxidative stress was evaluated by levels of 8-isoprostanes (EIA; Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI).(21) Intravenous glucose-tolerance test preceded CT scanning (10), with homeostasis model assessment of (HOMA-IR) serving as an index of IR (12).

In Vivo Imaging Studies

For each in vivo study, animals were weighed, induced with IM Telazol (5 mg/kg) and xylazine (2 mg/kg), intubated, and ventilated with room air. Anesthesia was maintained by ketamine (0.2 mg·kg−1·min−1) and xylazine (0.03 mg·kg−1·min−1) during CT scans, and inhaled isoflurane (1% to 2%) during MRI (due to its shorter procedure).

MRI.

BOLD-MRI (Signa EXCITE 3T; GE, Waukeshau, WI) was applied under 1% to 2% isoflurane anesthesia to evaluate myocardial oxygenation. Briefly, four to five axial-oblique BOLD images were acquired using Gated Fast Gradient Echo sequence with TR/TE/number of echoes/matrix size/field of view/slice thickness/flip angle = 6.8 ms/1.6–4.8 ms/8/128 × 128/35/0.5 cm/30°. The study was then repeated during infusion of adenosine (400 μg·kg−1·min−1) through the ear vein catheter. Data was processed in MATLAB 7.10 (MathWorks, Natick, MA) (31) to estimate the BOLD index, R2*. A region of interest (ROI) was traced at the lateral LV wall area-at-risk in T2*-weighted images, obtained under resting conditions and during adenosine infusion.

MDCT.

Sixty-four-slice MDCT (Somatom Definition-64; Siemens Medical Solution, Forchheim, Germany) scanning was performed 2 days after MRI to evaluate cardiac structure and function (30). Briefly, microvascular perfusion and function were evaluated in two 6-mm-thick parallel mid-LV levels. A bolus injection of contrast media (Iopamidol-370; 0.33 ml/kg over 2 s) into the right atrium was followed by a 50-s flow study (end-diastolic scans triggered every 1–3 heart beats), which was repeated 15 min later during a 5-min intravenous adenosine infusion (400 μg·kg−1·min−1). Subsequently, the entire LV was scanned 20 times throughout the cardiac cycle (cine sequence) to obtain cardiac systolic and diastolic functions and LV muscle mass (LVMM).

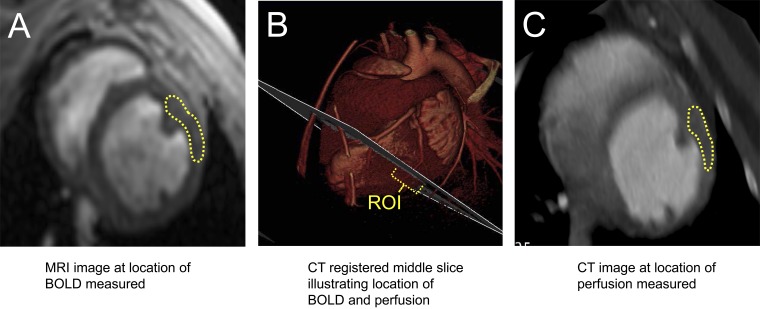

Images were analyzed with Analyze (Biomedical Imaging Resource; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) (30, 42). For LVMM, the borders of the end-diastolic LV endocardium and epicardium were traced at each tomographic level to sum the products of myocardial volume and specific gravity (41). LV cavity was also traced at end diastole and systole to calculate stroke volume, cardiac index (cardiac output per swine body surface area) (18), and LV ejection fraction (41). Systemic vascular resistance (SVR) was calculated as mean arterial pressure/(cardiac output). Early (E) and late (A) LV filling rates were calculated from the change in LV cavity volume during the cardiac cycle (41). Myocardial perfusion and microvascular permeability index were calculated from time-attenuation curves obtained before and during adenosine infusion from the lateral LV wall myocardium, as described (6). For MRI and CT, we selected similar lateral wall ROIs distal to the LCX stent (“area-at-risk”) (Fig. 1) based on anatomic landmarks. CAS was assessed in MDCT images as the decrease in luminal LCX diameter at the most stenotic compared with a stenosis-free segment (24). Myocardial vascular resistance was calculated as mean arterial pressure/(myocardial perfusion).

Fig. 1.

A–C: illustration of the selected levels and coregistration of MRI and computed tomography (CT) images. ROI, region of interest. BOLD, blood oxygenation level dependent.

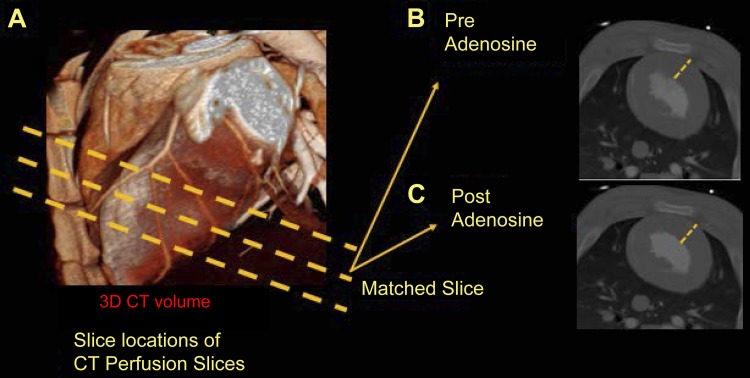

For regional cardiac function, wall thickness was measured in CT images obtained using the cine sequence at systole and diastole. The LV myocardium was manually traced at each level and phase (TeraRecon, Foster City, CA). The three-dimensional volume was fitted to a 17-segment polar map following the American Heart Association consensus and cardiac segments assigned to coronary artery perfusion territories (7). In addition, end-diastolic thickness (in the same lateral wall locations) was also measured on MDCT perfusion images acquired before and after adenosine infusion (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A–C: illustration of the selected levels and coregistration of MRI and CT images. 3D, 3-dimensional.

Fat measurement.

Intra-abdominal adipose tissue was expressed as volume and fraction (21, 22, 39). With the use of Analyze, the attenuation range of subcutaneous fat tissue was used to automatically threshold the adipose tissue through the entire image. Subsequently, an ROI was traced internally to the abdominal muscular wall. Intra-abdominal fat was calculated as a percentage of the selected abdominal area. For pericardial fat volume, ROI traced around the heart on the MDCT-derived cross-sections were expanded proportionally within the chest wall, bordered by the thoracic musculature and descending thoracic aorta. Pericardial fat was expressed as ratio to the entire cardiac volume.

In Vitro Studies

Angiogenic activity was evaluated by Western blotting of VEGF, its receptor fetal liver kinase (Flk)-1 (all Santa Cruz; 1:200), and myocardial hypoxia by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α.

Inflammation was investigated by double staining for macrophage markers CD163 (Serotec; 1:500) and iNOS (Millipore, 1:100) and by protein expression of IL-6 (Abcam; 1:1,000), total and phospho-NF-κB (p65), and TNF-α (all Santa-Cruz; 1:200). Cardiomyocyte-specific expression of iNOS was detected by double staining with Connexin-43.

Myocardial redox status was evaluated by in-situ production of superoxide anion, detected by dihydroethidium (DHE; 20 μM/l; Sigma) and by protein expression of the P47 (Santa Cruz; 1:200) and GP91 (Millipore; 1:500) subunits of NAD(P)H oxidase, and mitochondrial function by uncoupling protein-2 (UCP2; Abcam; 1:500).

Autophagy was assessed by protein expression of sirtuin-1 (SIRT1; Abcam; 1:5,000), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR; CST; 1:1,000), unc-51-like kinase-1 (ULK1; Abcam; 1:500), Beclin-1 (CST; 1:1,000), autophagy-related gene (Atg)-12 (CST; 1:1,000), and microtubule-associated protein-1 light-chain (LC)3 (LC3B; Abcam; 1:500).

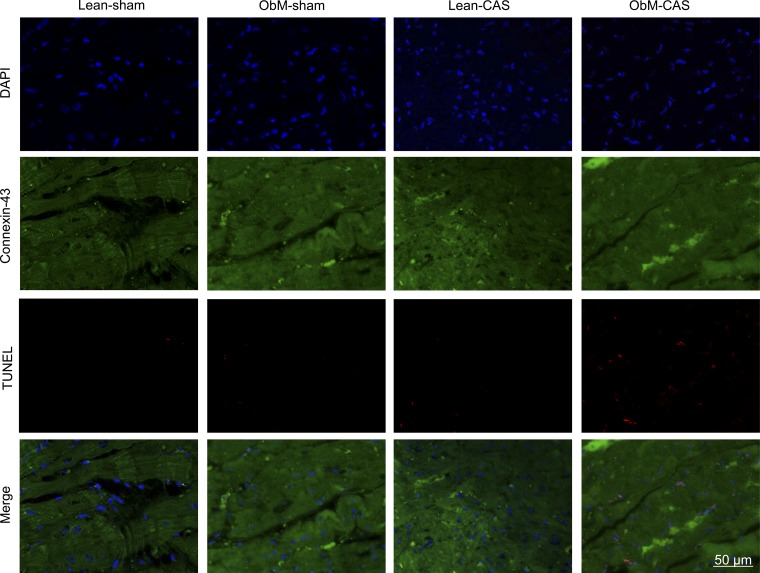

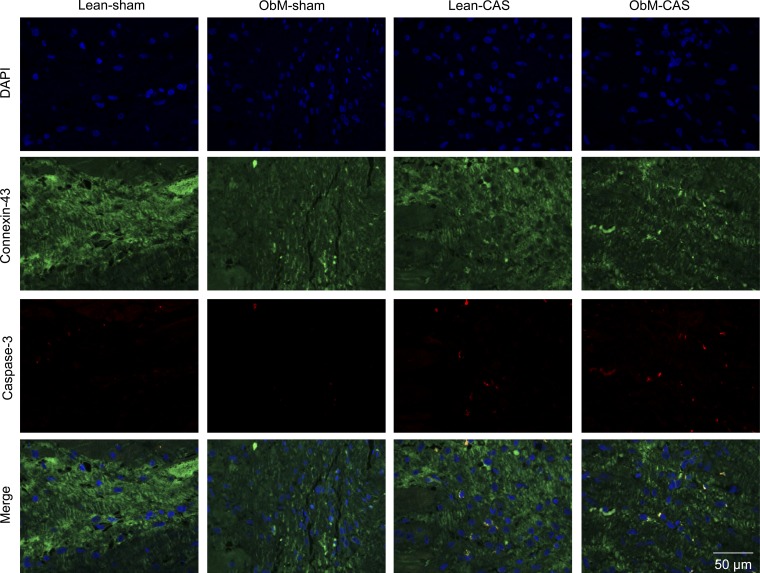

Apoptosis was evaluated by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and cleaved (active) caspase-3, each costained with Connexin-43, as well as expression of phospho-Akt (pAKT; CST; 1:1,000), Bcl-2 (Lifespan Biosciences; 1:1,000), and Bcl-xL and Bax (both Santa Cruz; 1:200).

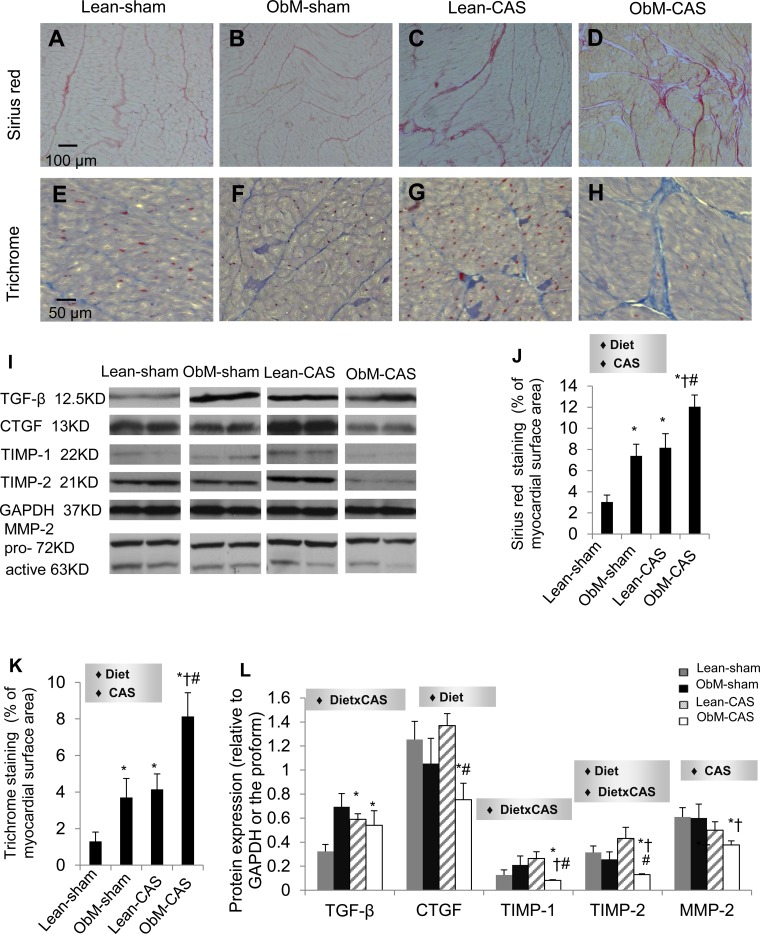

Fibrosis was studied by Sirius-red and trichrome staining, and protein expressions of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β; Santa Cruz; 1:1,000), connective tissue growth-factor (CTGF; BioVision; 1:500), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1 and TIMP-2 (Santa-Cruz, 1:200), and matrix-metalloproteinase (MMP)-2.

For Western blotting, GAPDH was used as loading control, except for pro-MMP-2, p-NF-κB, and total Akt for the corresponding activated proteins.

Micro-CT.

A side branch of the LCX coronary artery was perfused with a radio-opaque polymer (Microfil MV122; Flow Tech) under physiological pressure, and a transmural portion of the lateral wall myocardium distal to CAS then dissected and scanned (27, 30, 43). Subepicardial and subendocardial microvessels (MV) were counted and classified (27) by size using Analyze as small (diameters, 20–200 μm), medium (201–300 μm), or large (301–500 μm) (43).

Histology.

Staining performed in 5-μm-thick myocardial cross-sections was semiautomatically quantified in 15 random fields by a computer-aided image analysis program (MetaMorph; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) (30) and expressed as fraction of surface area or of total cells stained with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are expressed as means ± SE. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the effects of CAS and diet as well as their interactions (diet × CAS), followed by Tukey's test as appropriate. Comparisons within groups were performed using the paired Student's t-test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP software package version 9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Systemic Characteristics

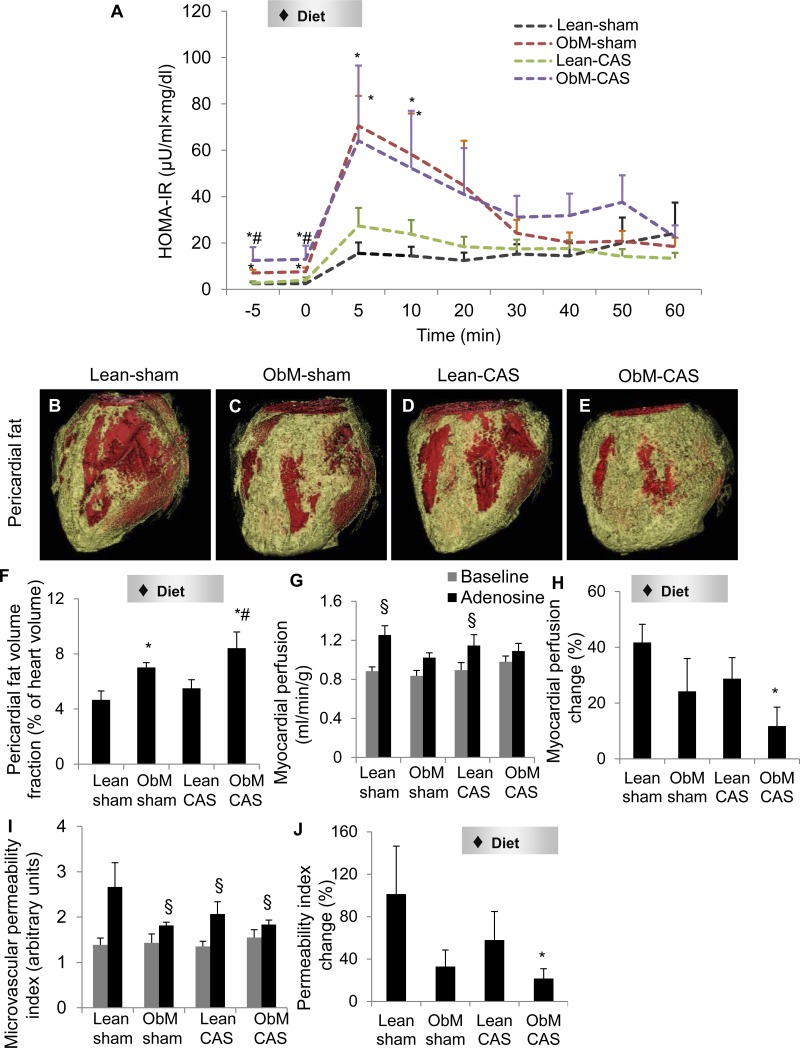

ObM diet increased body weight and visceral fat accumulation, elevated cholesterol fractions (Table 1), and induced IR compared with lean pigs, reflected by increased basal insulin levels and HOMA-IR (Table 1; Fig. 3A). MAP, heart rate, and RPP were unaffected by either diet or CAS, and nor were their responses to adenosine (Table 2). ObM diet increased peripheral level of leptin in both sham and CAS compared with Lean-sham, and MCP-1 in ObM-sham. Plasma TNF-α, endothelin-1, 8-epi-Isoprostane, and PRA were unchanged.

Table 1.

Metabolic, systemic, and cardiac traits of pigs with ObM and CAS

| Sham |

CAS |

P Value for Two-way ANOVA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean | ObM | Lean | ObM | Diet | CAS | Diet × CAS | |

| Body weight, kg | 34.0 ± 4.1 | 46.4 ± 4.6* | 34.6 ± 2.6 | 51.8 ± 2.1* # | 0.0009 | 0.06 | 0.33 |

| Intra-abdominal fat, % | 25.9 ± 3.4 | 41.2 ± 2.6* | 30.9 ± 2.8 | 44.1 ± 1.0* # | 0.0007 | 0.25 | 0.75 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | |||||||

| Total | 93.5 ± 2.2 | 513.8 ± 85.0* | 91.8 ± 9.4 | 435.4 ± 90.5* # | <.0001 | 0.54 | 0.56 |

| LDL | 34.7 ± 2.4 | 320.7 ± 67.0* | 32.8 ± 3.6 | 277.0 ± 61.4* # | <.0001 | 0.63 | 0.65 |

| HDL | 54.0 ± 1.5 | 185.0 ± 19.4* | 54.2 ± 6.2 | 148.8 ± 33.5* # | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| LDL/HDL | 0.6 ± 0.06 | 1.7 ± 0.2* | 0.6 ± 0.06 | 1.9 ± 0.3* # | <.0001 | 0.65 | 0.53 |

| Triglycerides | 24.0 ± 8.2 | 40.3 ± 17.6 | 24.2 ± 6.7 | 47.8 ± 15.7 | 0.14 | 0.77 | 0.78 |

| Insulin, μU/ml | 0.3 ± 0.07 | 0.8 ± 0.1* | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.6* # | 0.0076 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| MAP, mmHg | 113.0 ± 8.6 | 102.8 ± 13.2 | 102.0 ± 7.2 | 105.3 ± 6.8 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 0.61 |

| HR, beats/min | 64.0 ± 4.9 | 64.8 ± 8.5 | 59.0 ± 1.1 | 61.2 ± 5.2 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 0.88 |

| RPP, mmHg·beats−1·min−1 | 95.1 ± 12.3 | 88.1 ± 14.2 | 80.2 ± 4.9 | 84.1 ± 8.8 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.52 |

| Plasma renin activity, ng·ml−1·h−1 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.2 ± 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| Leptin, ng/ml | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 12.0 ± 1.3* | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 14.4 ± 4.0* | 0.0177 | 0.43 | 0.94 |

| Plasma TNF-α, pg/ml | 53.3 ± 15.8 | 57.2 ± 13.9 | 47.7 ± 11.1 | 47.4 ± 8.2 | 0.88 | 0.55 | 0.89 |

| Plasma monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, pg/ml | 280.4 ± 29.7 | 436.6 ± 65.0* | 251.7 ± 69.6 | 410.7 ± 59.7 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

| Endothelin-1, pg/ml | 30.0 ± 1.3 | 49.8 ± 11.7 | 32.0 ± 1.4 | 49.8 ± 12.1 | 0.07 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| 8-Epi-isoprostane, pg/ml | 398.4 ± 108.1 | 451.6 ± 114.0 | 355.3 ± 59.1 | 1247.1 ± 371.3 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Left ventricular muscle mass, g | 51.7 ± 4.0 | 54.5 ± 7.4 | 54.7 ± 3.3 | 65.7 ± 4.2 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.42 |

| E/A | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.11 |

| Stroke volume, ml | 39.3 ± 2.6 | 34.5 ± 5.0 | 35.5 ± 1.9 | 38.9 ± 4.4 | 0.86 | 0.48 | 0.36 |

| Cardiac index, l·min−1·m2−1 | 3.2 ± 0.05 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.05 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.47 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 63.3 ± 5.7 | 61.5 ± 3.2 | 57.6 ± 2.1 | 61.0 ± 3.3 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.44 |

| Systemic vascular resistance, mmHg·min−1·l−1 | 45.4 ± 2.4 | 49.0 ± 7.5 | 48.5 ± 4.3 | 50.1 ± 11.0 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 1.00 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 6 each. ObM, obesity-metabolic derangements; MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate; RPP, rate-pressure product.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-sham;

P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-coronary artery stenosis (CAS).

Fig. 3.

Insulin resistance, cardiac remodeling, and myocardial perfusion. Intravenous glucose tolerance tests indicated insulin resistance in obesity-metabolic derangements (ObM; A). Representative CT images (B–E) and quantification (F) of pericardial fat (yellow) are shown. Basal myocardial perfusion was not different among the groups, whereas the response to adenosine was blunted in ObM pigs (G and H), suggesting microvascular dysfunction. The response of microvascular permeability to adenosine was also diminished in ObM pigs, implicating impaired integrity (H). I: microvascular permeability index. J: permeability index change in response to adenosine. HOMA-IR, homeostasis-model-assessment insulin resistance; CAS, coronary artery stenosis. ♦Significant effect by 2-way ANOVA; *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-sham; #P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-CAS; §P ≤ 0.05 vs. baseline.

Table 2.

Hemodynamic data before and after adenosine during computed tomography scanning

| Sham |

CAS |

P Value for Two-way ANOVA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean | ObM | Lean | ObM | Diet | CAS | Diet × CAS | |

| MAP, mmHg | |||||||

| Baseline | 113.0 ± 8.6 | 102.8 ± 13.2 | 102.0 ± 7.2 | 105.3 ± 6.8 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 0.61 |

| Adenosine | 95.9 ± 12.1 | 87.8 ± 12.6 | 88.7 ± 5.8 | 90.5 ± 5.9 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.59 |

| Change, % | −15.7 ± 5.1 | −14.9 ± 2.9 | −12.8 ± 1.8 | −13.9 ± 2.5 | 0.96 | 0.54 | 0.76 |

| HR, beats/min | |||||||

| Baseline | 64.0 ± 4.9 | 64.8 ± 8.5 | 59.0 ± 1.1 | 61.2 ± 5.2 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 0.88 |

| Adenosine | 102 ± 6.1 | 89.8 ± 11.8 | 92.0 ± 7.0 | 88.8 ± 5.7 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.24 |

| Change, % | 63.6 ± 19.7 | 41.2 ± 15.9 | 56.6 ± 14.1 | 46.2 ± 5.3 | 0.26 | 0.95 | 0.68 |

| RPP, mmHg·beats−1·min−1 | |||||||

| Baseline | 95.1 ± 12.3 | 88.1 ± 14.2 | 80.2 ± 4.9 | 84.1 ± 8.8 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.52 |

| Adenosine | 121.1 ± 9.0 | 103.5 ± 15.3 | 107.1 ± 8.4 | 105.3 ± 11.3 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.49 |

| Change, % | 30.6 ± 10.2 | 20.9 ± 11.4 | 34.1 ± 9.0 | 25.2 ± 2.4 | 0.30 | 0.65 | 0.96 |

| Myocardial vascular resistance, mmHg/(ml·min−1·g−1) | |||||||

| Baseline | 167.7 ± 13.3 | 162.1 ± 16.1 | 158.3 ± 20.7 | 142.0 ± 11.9 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.75 |

| Adenosine | 96.5 ± 8.7 | 113.3 ± 8.5 | 105.3 ± 10.4 | 108.9 ± 6.2 | 0.26 | 0.81 | 0.46 |

| Change, % | −42.1 ± 4.6 | −29.0 ± 5.8 | −32.2 ± 3.8 | −21.8 ± 5.7* | 0.0359 | 0.11 | 0.79 |

Values are means ± SE.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-sham.

Hemodynamics and Cardiac Function

LVMM, stroke volume, cardiac index, ejection fraction, E/A ratio, and SVR were not influenced by diet or CAS (Table 1), nor were end-diastolic wall thickness (representing regional function) and its response to adenosine (Table 3). CAS decreased end-diastolic apical lateral thickness in ObM but not lean pigs compared with ObM sham (Table 4), whereas other walls were unaffected. Although basal and post-adenosine myocardial perfusion were unchanged by either factor, its response to adenosine (myocardial perfusion change percentage) was only diminished in ObM-CAS by the ObM diet (Fig. 3, G and H). ObM diet also reduced the responses of permeability index (Fig. 3, I and J) and MVR to adenosine (Table 2) in ObM-CAS. Therefore, ObM hampered myocardial microvascular function, which was magnified by the presence of CAS.

Table 3.

Change in left ventricular thickness in response to adenosine measure with computed tomography at end diastole

| Sham |

CAS |

P Value for Two-way ANOVA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean | ObM | Lean | ObM | Diet | CAS | Diet × CAS | |

| Septum, mm | |||||||

| Baseline | 7.3 ± 0.6 | 7.3 ± 0.4 | 7.2 ± 0.8 | 7.7 ± 0.1 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.64 |

| Adenosine | 7.5 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 0.5 | 7.4 ± 0.9 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.68 |

| Change, % | 2.5 ± 2.6 | 1.3 ± 5.5 | 1.3 ± 3.6 | 0.1 ± 2.8 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 1.00 |

| Anterior wall, mm | |||||||

| Baseline | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 6.3 ± 0.5 | 0.65 | 0.99 | 0.76 |

| Adenosine | 7.2 ± 0.9 | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 0.88 | 0.38 | 0.62 |

| Change, % | 9.3 ± 5.2 | 22.0 ± 20.5 | 6.7 ± 7.7 | 0.8 ± 2.6 | 0.74 | 0.24 | 0.36 |

| Lateral wall, mm | |||||||

| Baseline | 8.7 ± 0.5 | 8.3 ± 0.7 | 7.9 ± 0.3 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 0.86 | 0.55 | 0.35 |

| Adenosine | 9.2 ± 0.7 | 9.5 ± 0.4 | 8.6 ± 0.5 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 0.68 | 0.23 | 0.92 |

| Change, % | 5.0 ± 3.1 | 15.1 ± 8.9 | 8.6 ± 8.5 | 3.0 ± 4.5 | 0.71 | 0.49 | 0.21 |

Values are means ± SE.

Table 4.

Change in left ventricular thickness measured with computed tomography during the cardiac cycle

| Sham |

CAS |

P Value for Two-way ANOVA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean | ObM | Lean | ObM | Diet | CAS | Diet × CAS | |

| Middle inferolateral, mm | |||||||

| End diastole | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 8.0 ± 1.7 | 6.8 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 0.7 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.34 |

| End systole | 11.3 ± 0.7 | 10.3 ± 1.0 | 9.0 ± 0.8 | 9.4 ± 0.7 | 0.70 | 0.09 | 0.41 |

| Change, % | 88.3 ± 33.7 | 45.7 ± 29.9 | 33.9 ± 12.8 | 49.3 ± 10.0 | 0.54 | 0.26 | 0.20 |

| Middle anterolateral, mm | |||||||

| End diastole | 9.0 ± 1.5 | 9.0 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 0.6 | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 0.76 | 0.97 | 0.76 |

| End systole | 15.0 ± 1.5 | 13.5 ± 1.0 | 11.8 ± 0.6 | 12.8 ± 0.7 | 0.82 | 0.06 | 0.21 |

| Change, % | 73.4 ± 22.7 | 50.2 ± 10.6 | 36.7 ± 13.5 | 41.3 ± 13.8 | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.37 |

| Apical lateral, mm | |||||||

| End diastole | 7.3 ± 0.3 | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 6.6 ± 0.2† | 0.56 | 0.0400 | 0.15 |

| End systole | 12.0 ± 1.2 | 11.5 ± 0.9 | 10.8 ± 0.5 | 10.6 ± 0.7 | 0.69 | 0.20 | 0.83 |

| Change, % | 65.5 ± 21.9 | 42.4 ± 16.1 | 55.7 ± 13.3 | 61.0 ± 9.3 | 0.55 | 0.77 | 0.35 |

Values are means ± SE.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. ObM-sham.

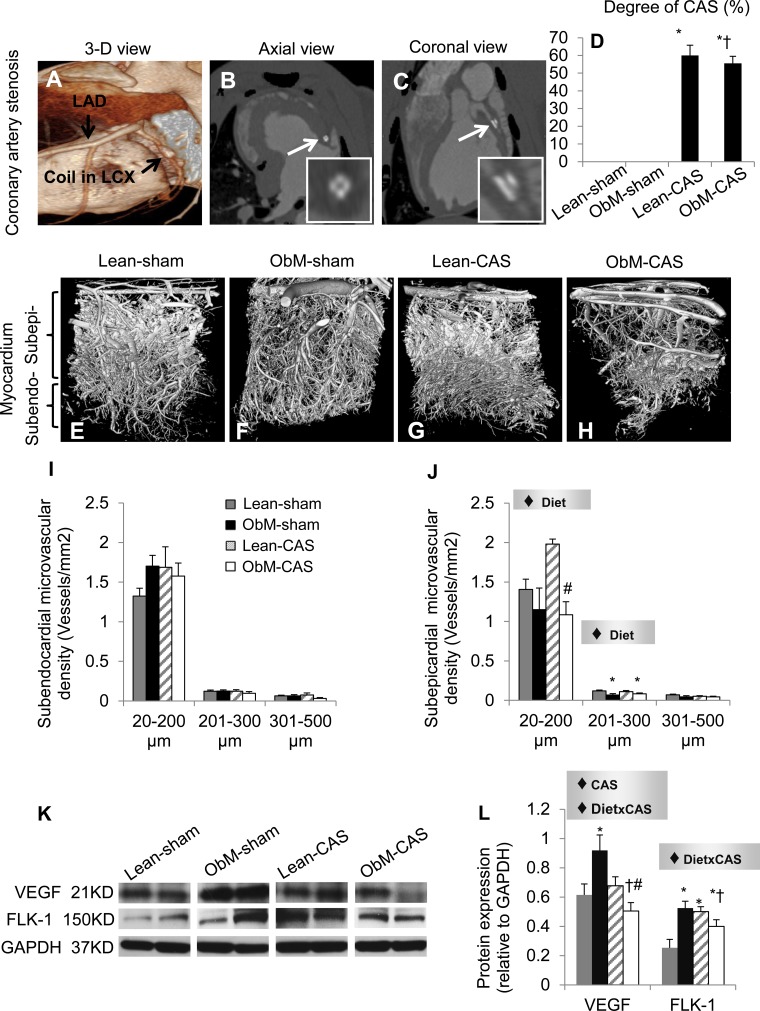

Vascular Structure and Cardiac Adiposity

Comparable moderate stenoses were achieved in Lean-CAS and ObM-CAS pigs (Fig. 4, A–D), and ObM diet similarly thickened epicardial fat in both sham and CAS pigs (Fig. 3, B–F). Although subendocardial MV density was unchanged, ObM diet blunted the density of subepicardial small and medium-size vessels in CAS compared with Lean-CAS and Lean-sham, respectively (Fig. 4, E–J). Moreover, although CAS and ObM alone upregulated the expression of VEGF and FLK-1, ObM-CAS suppressed VEGF and FLK-1 compared with its controls, mediated by the effects of CAS and its synergistic interaction with diet (Fig. 4, K and L). Taken together, coexistence of ObM and CAS interfered with maintenance of myocardium microcirculation.

Fig. 4.

Cardiac vascular remodeling. Representative 3-dimensional tomographic images of CAS (A–C) and the myocardial microcirculation (E–H) and quantification of CAS (D), subendocardial (I), and subepicardial (J) microvascular density are shown. K and L: myocardial protein expression of VEGF and fetal liver kinase (FLK)-1. LCX, left circumflex. ♦Significant effect by 2-way ANOVA; *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-sham; †P ≤ 0.05 vs. ObM-sham; #P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-CAS. Subendo, subendocardial; Subepi, subepicardial.

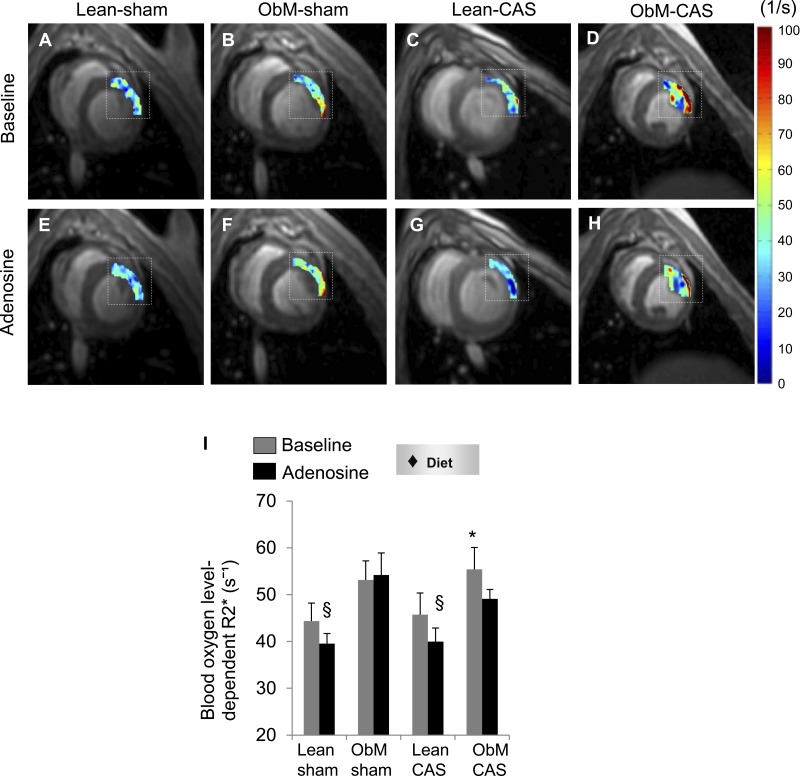

Myocardial Oxygenation

In concert with its effects on microvascular function and microcirculation, ObM diet elevated basal lateral wall R2* only in CAS. Moreover, although their ΔR2* was comparable (data not shown), the R2* responses observed in lean pigs were diminished in ObM and ObM-CAS pigs (Fig. 5, A–I), suggesting ObM diet-elicited myocardial hypoxia.

Fig. 5.

Myocardial oxygenation in ObM-CAS. Blood oxygen level-dependent MRI (dashed box indicates region of interest; A–H) and R2* quantification (I) showed hypoxia. ♦Significant effect by 2-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-sham; §P ≤ 0.05 vs. baseline.

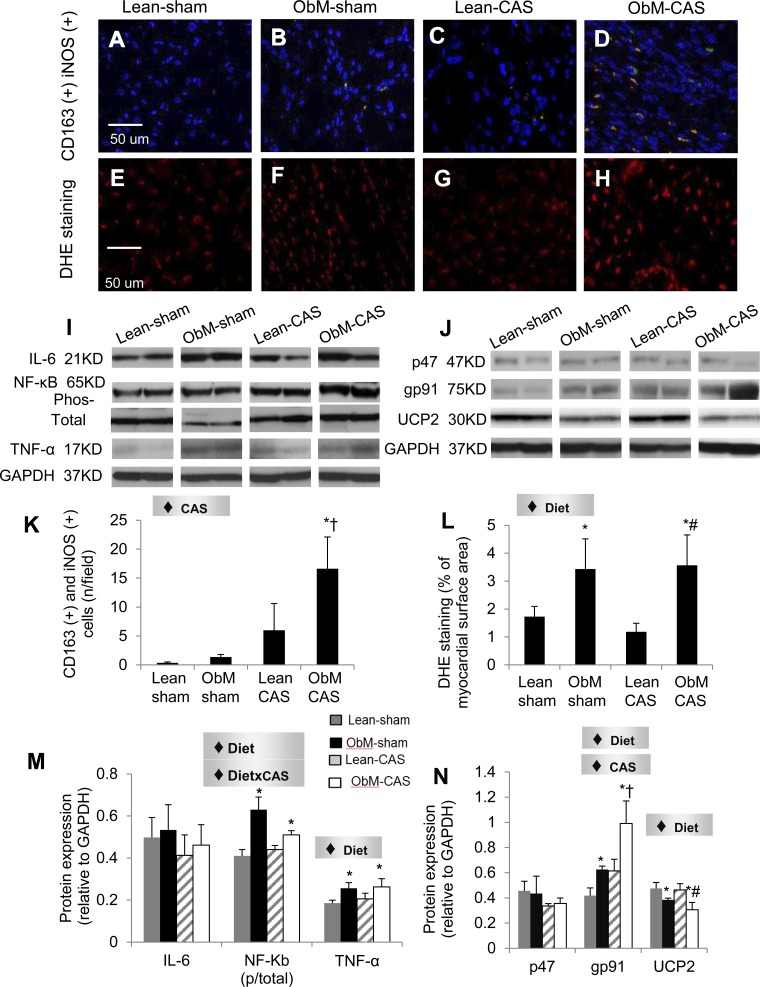

Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

CAS magnified the myocardial infiltration of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages only in ObM pigs (Fig. 6) and cardiomyocyte iNOS immunoreactivity in both lean and ObM pigs (Fig. 7). Diet also uniformly stimulated the iNOS immunoreactivity (Fig. 7) and expression of TNF-α (Fig. 6M). Interestingly, increased ratio of phospho-to-total NF-κB in ObM-sham was suppressed by the interaction diet × CAS. Diet also increased DHE staining and elevated the expression of gp91, which was further aggravated by CAS (Fig. 6N). Furthermore, UCP2, an important mitochondrial antioxidant (9), was suppressed by diet in both sham and CAS pigs (Fig. 6N). These data suggest additive effects of ObM and CAS on inflammation and oxidative stress, which may contribute to distinct injuries in ObM-CAS.

Fig. 6.

Myocardial inflammation and oxidative stress. CD163 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) double staining (A–D, K) and myocardial protein expression of inflammatory mediators (I, M) IL-6, NF-κB (phosphorylated and total), and TNF-α are shown. Dihydroethidium (DHE; E–H, L) staining, and protein expression of oxidative stress markers (J, N) P47, GP91, and the mitochondrial uncoupling protein-2 (UCP2) protein expression was normalized to GAPDH, except for phosphor/total NF-κB. ♦Significant effect by 2-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-sham; †P ≤ 0.05 vs. ObM-sham; #P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-CAS.

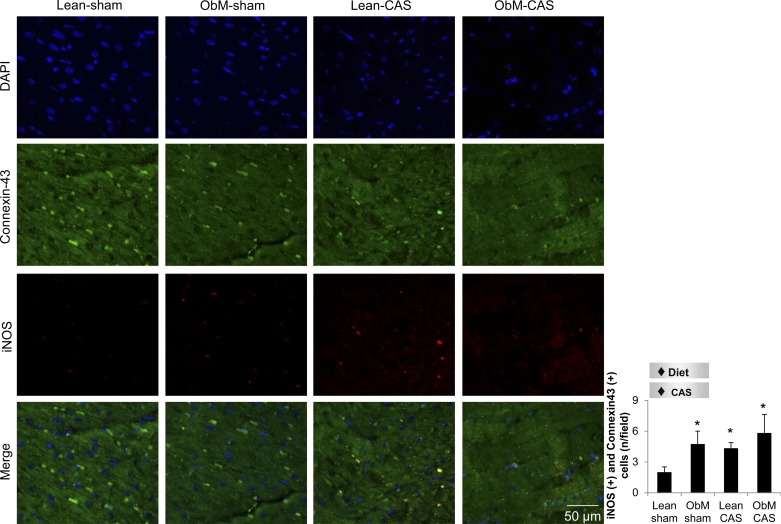

Fig. 7.

Representative images for costaining of iNOS (red) and connexin-43 (green) and its quantification. ♦Diet, significant effect of ObM diet; ♦CAS, significant effect of CAS. *P < 0.05 vs. Lean-sham. DAPI, 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

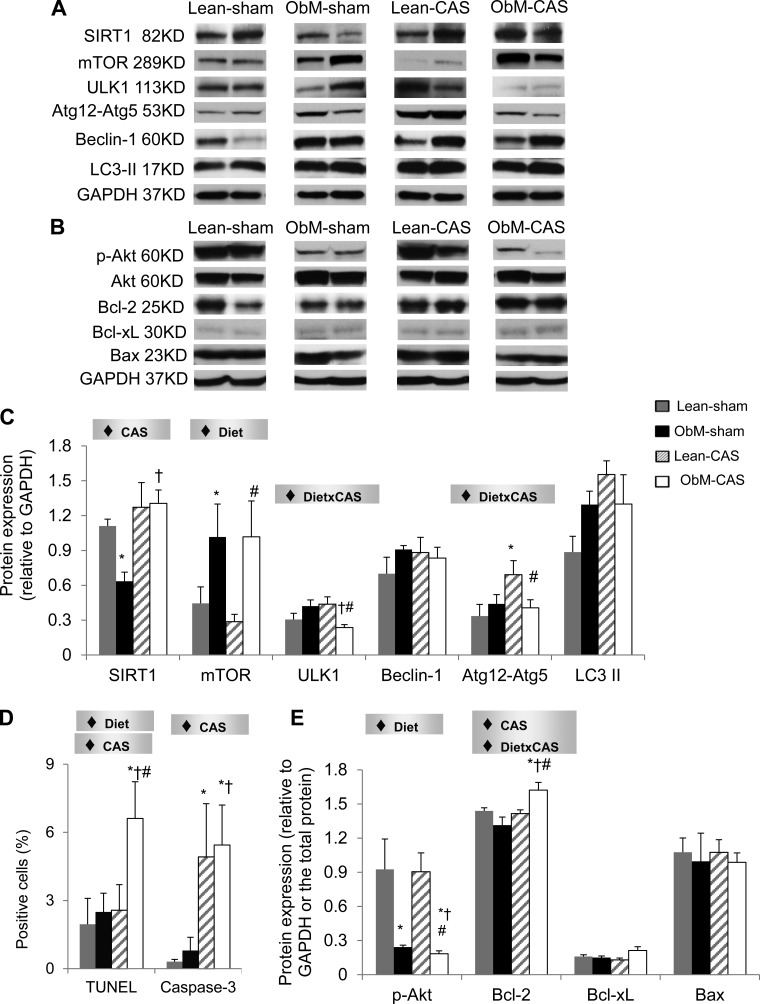

Autophagy and Apoptosis

SIRT1, a key sensor of energy availability (20), was elevated by CAS in ObM pigs compared with ObM-sham, in which its expression contrarily declined (Fig. 8), suggesting excessive nutrient availability in ObM-sham that was deprived by CAS. This was accompanied by upregulation of Atg12-Atg5 in Lean-CAS, indicating increased autophagic activity. However, diet enhanced the expression of mTOR, a major inhibitor of autophagy, and interacted with CAS to attenuate ULK1 and autophagy initiators Atg12-Atg5. These data showed that ObM counteracts the pro-autophagic effect of CAS and may thereby disrupt cellular recycling.

Fig. 8.

Myocardial autophagy and apoptosis. Myocardial protein expression of autophagy-related proteins including sirtuin-1 (SIRT1), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), unc-51-like kinase-1 (ULK1), Beclin-1, autophagy-related gene (Atg)-12, and microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain (LC) 3II (A, C) is shown. Quantification of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and caspase-3 costained with Connexin-43 (D; see Supplemental Figs. S4 and S5) and myocardial expression of Akt, B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), B-cell lymphoma-extra-large (Bcl-xL), and Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) (B, E) are shown. ♦Significant effect by 2-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-sham; †P ≤ 0.05 vs. ObM-sham; #P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-CAS.

CAS and diet stimulated apoptosis in ObM-CAS by raising the numbers of Caspase-3 and TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes (Figs. 8D, 9, and 10). In addition, ObM inhibited the expression of the survival factor p-Akt in sham-ObM and further in ObM-CAS compared with ObM-sham. Therefore, both ObM and CAS had pro-apoptotic effects. Interestingly, the apoptosis inhibitor Bcl-2 was also upregulated in ObM-CAS by the effects of CAS and diet × CAS, possibly as a compensatory response to pronounced apoptosis in this group (Fig. 8D). Bcl-xL and Bax expression were unaltered (Fig. 8).

Fig. 9.

Representative images of TUNEL (red) and Connexin-43 (green) double staining. Quantification is shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 10.

Representative images of caspase-3 (red) and Connexin-43 (green) double staining. Quantification is shown in Fig. 8.

Myocardial Fibrosis

ObM diet and CAS magnified both Sirius red and trichrome staining, both of which were most pronounced in ObM-CAS (Fig. 11). Interestingly, although expression of TGF-β was upregulated in both Lean-CAS and ObM-CAS, other profibrotic mediators, CTGF, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and MMP-2, were uniformly reduced only in ObM-CAS, by the effects of diet, CAS, or their interaction. Given marked interstitial fibrosis formation in ObM-CAS, downregulation of fibrotic mediators in these animals may imply completion of active myocardial remodeling.

Fig. 11.

Myocardial fibrosis. Sirius red (A–D) and Trichrome (E–H) staining and quantifications (J and K) are shown; myocardial protein expression of the fibrogenic factors (I, L) transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1 and TIMP-2, and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 is shown. ♦Significant effect by 2-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-sham; †P ≤ 0.05 vs. ObM-sham; #P ≤ 0.05 vs. Lean-CAS.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that experimental ObM, characterized by visceral obesity, hyperlipidemia, and IR, interferes with myocardial remodeling in moderate CAS. Importantly, we observed synergistic interactions between the ObM and CAS to blunt compensatory angiogenic, autophagic, and fibrogenic activities in the myocardium, which may affect the adequacy and progression of cardiac remodeling. These findings may implicate ObM in the pathophysiological mechanisms of CAD and in its maladaptation to otherwise moderate ischemic insults.

Coronary blood flow often does not decline until CAS exceeds 70% luminal area obstruction (33), although hyperemic responses to adenosine might be blunted distal to intermediate lesions of 50–70%. In contrast with Lean-CAS pigs that had preserved myocardial hemodynamics and microvasculature, ObM-CAS, which bore comparable occlusion of the coronary artery, reduced microvascular function and density and inhibited compensatory angiogenic activities. Such effects may account for the association of ObM with increased inducible myocardial ischemia observed in patients with subclinical atherosclerosis (35). Indeed, the magnitude of stenosis may be discordant with the degree of ischemia (5, 29), where ObM might modulate myocardial remodeling downstream to CAS. Considering the unchanged oxygen consumption (RPP), myocardial hypoxia in ObM-CAS (R2*) might be at least partially secondary to ObM-induced MV dysfunction (2). In addition, interference of ObM-induced IR with adaptive switches of glucose utilization during myocardial ischemia from FFA metabolism to the more efficient fuel glucose may also play a role (34). This hypothesis was supported by the observation that pAkt, a critical promoter of glucose metabolism (32), was markedly repressed by ObM. Therefore, deregulation of glucose utilization by co-existence of ObM and CAS diminished energy availability in ObM-CAS, as reflected by reciprocal expression patterns of SIRT1 in ObM-sham. Moreover, enriched pericardial fat by ObM may also aggravate myocardial hypoxia compared with Lean-CAS (28).

Similar to the kidney of obese pigs (21), ObM alone tended to increase angiogenic activity in the ObM myocardium. Nevertheless, neovessels in ObM often exhibit impaired integrity and thus may facilitate tissue damage distal to CAS by allowing extravasation of inflammatory cells and mediators, which as a result further exacerbates microvascular function and formation. This notion is supported by diminished responses of perfusion and permeability index to adenosine only in ObM-CAS and suppressed angiogenic activity by synergistic interaction of ObM and CAS, although overall contractile and diastolic cardiac function in ObM-CAS was relatively preserved. Additionally, ObM additively enhanced oxidative stress (DHE staining, gp91 expression) in CAS, which further degrades VEGF. Inhibited expression of UCP2 by ObM also underscores its potential association with mitochondrial dysfunction (4), which may disrupt MV maintenance and repair in ObM-CAS.

To ameliorate cellular damage, autophagy limits apoptosis (36) by allowing recycling amino acids under nutrient deprivation conditions, such as CAS. This mechanism, however, was disarrayed in ObM-CAS. In addition to chronic lipid load (19) and elevated cytokines (16) that may blunt autophagy in ObM, cardiac mTOR signaling is activated in hypercholesterolemia (13) and persists in hyperinsulinemia (15, 44), thus counteracting activated autophagy in CAS, which subsequently leads to accumulation of damaged mitochondria and cardiomyocyte apoptosis (36). NF-κB activates autophagy, and its downregulation has been shown to induce a switch from autophagy to apoptosis, as we observed in ObM-CAS (17). Moreover, decreased activation of the survival factor Akt also amplifies cell death and loss of functional components, which aggravates post-stenotic cardiac remodeling (1). Indeed, interstitial fibrosis was magnified in ObM-CAS compared with Lean-CAS. Alas, except for the increased expression of TGF-β, downregulation of multiple other fibrotic mediators in ObM-CAS suggests earlier completion of fibrotic process in these animals,. Thus ObM offsets protective autophagic activity by CAS, induces apoptosis, interferes with tissue remodeling, and thus may play a critical role in the cascade and progression of cardiac injury in ObM-CAS.

Limitations

The present study design did not allow defining effects of individual components of the ObM constellation on myocardial structure and function. Indeed, our preclinical swine model of ObM successfully recapitulates the complexity of human disease and thus allows elucidating myocardial pathophysiology at the early stage of CAS. We evaluated the effects of ObM in moderate CAS because measureable differences in myocardial remodeling are easier to detect before severe ischemia and fibrosis set in. Further studies are needed to evaluate its impact on higher grades of CAS and in humans. The temporal effects of ObM-CAS on the renin-angiotensin system and fibrogenic pathways also warrant additional investigation.

In summary, our study demonstrated exacerbation of myocardial pathophysiological changes distal to moderate CAS in experimental ObM. ObM inhibited myocardial autophagy that was upregulated by CAS alone, which may in turn exacerbate MV dysfunction, apoptosis, and tissue remodeling. These observations suggest that in subjects with ObM, intermediate coronary artery obstructions, which might often be considered hemodynamically insignificant, might in fact be consequential and impair downstream myocardial structure and function. These issues need to be considered in patient management decisions.

GRANTS

This study was partly supported by National Institute of Health Grants DK-73608, HL-77131, HL-121561, and C06-RR018898. Z.-L. Li was supported by the China Scholarship Council under the authority of the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: Z.-L.L. and L.O.L. conception and design of research; Z.-L.L., B.E., X.Z., J.R.W., and H.T. performed experiments; Z.-L.L., B.E., X.Z., A.E., J.R.W., H.T., A.L., S.W., and L.O.L. analyzed data; Z.-L.L., B.E., X.Z., A.E., J.R.W., H.T., A.L., S.W., and L.O.L. interpreted results of experiments; Z.-L.L. prepared figures; Z.-L.L. drafted manuscript; Z.-L.L., A.L., S.W., and L.O.L. edited and revised manuscript; Z.-L.L., B.E., X.Z., A.E., J.R.W., A.L., S.W., and L.O.L. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldi A, Abbate A, Bussani R, Patti G, Melfi R, Angelini A, Dobrina A, Rossiello R, Silvestri F, Baldi F, Di Sciascio G. Apoptosis and post-infarction left ventricular remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 165–174, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bender SB, Tune JD, Borbouse L, Long X, Sturek M, Laughlin MH. Altered mechanism of adenosine-induced coronary arteriolar dilation in early-stage metabolic syndrome. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 234: 683–692, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berwick ZC, Dick GM, Moberly SP, Kohr MC, Sturek M, Tune JD. Contribution of voltage-dependent K+ channels to metabolic control of coronary blood flow. J Mol Cell Cardiol 52: 912–919, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bugger H, Abel ED. Molecular mechanisms for myocardial mitochondrial dysfunction in the metabolic syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond) 114: 195–210, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bugiardini R, Merz CNB. Angina with “normal” coronary arteries a changing philosophy. JAMA 293: 477–484, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caceres VHU, Lin J, Zhu XY, Favreau FD, Gibson ME, Crane JA, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Early experimental hypertension preserves the myocardial microvasculature but aggravates cardiac injury distal to chronic coronary artery obstruction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H693–H701, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, Pennell DJ, Rumberger JA, Ryan T, Verani MS. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation 105: 539–542, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly CA, Hildebrandt P, Bertrand M, Ferrari R, Remme W, Simoons M, Fox KM, Investigators E Adverse prognosis associated with the metabolic syndrome in established coronary artery disease: data from the EUROPA trial. Heart 93: 1406–1411, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diano S, Horvath TL. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) in glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Mol Med 18: 52–58, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyson MC, Alloosh M, Vuchetich JP, Mokelke EA, Sturek M. Components of metabolic syndrome and coronary artery disease in female ossabaw swine fed excess atherogenic diet. Comp Med 56: 35–45, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ervin RB. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults 20 years of age and over, by sex, age, race and ethnicity, and body mass index: United States, 2003–2006. Natl Health Stat Report 13: 1–7, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galili O, Versari D, Sattler KJ, Olson ML, Mannheim D, McConnell JP, Chade AR, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Early experimental obesity is associated with coronary endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H904–H911, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glazer HP, Osipov RM, Clements RT, Sellke FW, Bianchi C. Hypercholesterolemia is associated with hyperactive cardiac mTORC1 and mTORC2 signaling. Cell Cycle 8: 1738–1746, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gobel FL, Norstrom LA, Nelson RR, Jorgensen CR, Wang Y. The rate-pressure product as an index of myocardial oxygen consumption during exercise in patients with angina pectoris. Circ Res 57: 549–556, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez CD, Lee MS, Marchetti P, Pietropaolo M, Towns R, Vaccaro MI, Watada H, Wiley JW. The emerging role of autophagy in the pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus. Autophagy 7: 2–11, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris J, De Haro SA, Master SS, Keane J, Roberts EA, Delgado M, Deretic V. T helper 2 cytokines inhibit autophagic control of intracellular mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunity 27: 505–517, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Q, Wang Y, Li T, Shi K, Li Z, Ma Y, Li F, Luo H, Yang Y, Xu C. Heat shock protein 90-mediated inactivation of nuclear factor-kappaB switches autophagy to apoptosis through becn1 transcriptional inhibition in selenite-induced NB4 cells. Mol Biol Cell 22: 1167–1180, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelley KW, Curtis SE, Marzan GT, Karara HM, Anderson CR. Body surface area of female swine. J Anim Sci 36: 927–930, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koga H, Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. Altered lipid content inhibits autophagic vesicular fusion. FASEB J 24: 3052–3065, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F, Messadeq N, Milne J, Lambert P, Elliott P, Geny B, Laakso M, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1 alpha. Cell 127: 1109–1122, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Woollard JR, Wang S, Korsmo MJ, Ebrahimi B, Grande JP, Textor SC, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Increased glomerular filtration rate in early metabolic syndrome is associated with renal adiposity and microvascular proliferation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F1078–F1087, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li ZL, Woollard JR, Ebrahimi B, Crane JA, Jordan KL, Lerman A, Wang SM, Lerman LO. Transition from obesity to metabolic syndrome is associated with altered myocardial autophagy and apoptosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 1132–1141, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marroquin OC, Kip KE, Kelley DE, Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Merz CNB, Sharaf BL, Pepine CJ, Sopko G, Reis SE, Investigators W Metabolic syndrome modifies the cardiovascular risk associated with angiographic coronary artery disease in women—A report from the Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Circulation 109: 714–721, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng V, Chinnaiyan K, Chow BJW, Delago A, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J, Kaufmann P, Maffei E, Raff G, Shaw LJ, Villines T, Berman DS, Investigators C Age- and Sex-Related Differences in All-Cause Mortality Risk Based on Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography Findings Results From the International Multicenter CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter Registry) of 23,854 Patients Without Known Coronary Artery Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 849–860, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nigam A, Bourassa MG, Fortier A, Guertin MC, Tardif JC. The metabolic syndrome and its components and the long-term risk of death in patients with coronary heart disease. Am Heart J 151: 514–520, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson LR, Herrero P, Schechtman KB, Racette SB, Waggoner AD, Kisrieva-Ware Z, Dence C, Klein S, Marsala J, Meyer T, Gropler RJ. Effect of obesity and insulin resistance on myocardial substrate metabolism and efficiency in young women. Circulation 109: 2191–2196, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez-Porcel M, Lerman A, Ritman EL, Wilson SH, Best PJM, Lerman LO. Altered myocardial microvascular 3D architecture in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Circulation 102: 2028–2030, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamarappoo B, Dey D, Shmilovich H, Nakazato R, Gransar H, Cheng VY, Friedman JD, Hayes SW, Thomson LEJ, Slomka PJ, Rozanski A, Berman DS. Increased pericardial fat volume measured from noncontrast CT predicts myocardial ischemia by SPECT. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 3: 1104–1112, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tonino PAL, Fearon WF, De Bruyne B, Oldroyd KG, Leesar MA, Lee PNV, MacCarthy PA, van′t Veer M, Pijls NHJ. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol 55: 2816–2821, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urbieta Caceres VH, Lin J, Zhu XY, Favreau FD, Gibson ME, Crane JA, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Early experimental hypertension preserves the myocardial microvasculature but aggravates cardiac injury distal to chronic coronary artery obstruction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H693–H701, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warner L, Glockner JF, Woollard J, Textor SC, Romero JC, Lerman LO. Determinations of renal cortical and medullary oxygenation using blood oxygen level-dependent magnetic resonance imaging and selective diuretics. Invest Radiol 46: 41–47, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whiteman EL, Cho H, Birnbaum MJ. Role of Akt/protein kinase B in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13: 444–451, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson RF, Marcus ML, White CW. Prediction of the physiologic significance of coronary arterial lesions by quantitative lesion geometry in patients with limited coronary artery disease. Circulation 75: 723–732, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witteles RM, Fowler MB. Insulin-resistant cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 51: 93–102, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong ND, Rozanski A, Gransar H, Miranda-Peats R, Kang XP, Hayes S, Shaw L, Friedman J, Polk D, Berman DS. Metabolic syndrome and diabetes are associated with an increased likelihood of inducible myocardial ischemia among patients with subclinical atherosclerosis. Diabetes Care 28: 1445–1450, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan L, Vatner DE, Kim SJ, Ge H, Masurekar M, Massover WH, Yang GP, Matsui Y, Sadoshima J, Vatner SF. Autophagy in chronically ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 13807–13812, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang L, Li P, Fu SN, Calay ES, Hotamisligil GS. Defective hepatic autophagy in obesity promotes ER stress and causes insulin resistance. Cell Metab 11: 467–478, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu CM, Lin H, Yang H, Kong SL, Zhang Q, Lee SWL. Progression of systolic abnormalities in patients with “isolated” diastolic heart failure and diastolic dysfunction. Circulation 105: 1195–1201, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X, Li ZL, Woollard JR, Eirin A, Ebrahimi B, Crane JA, Zhu XY, Pawar A, Krier JD, Jordan KL, Tang H, Textor SC, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Obesity-metabolic derangement preserves hemodynamics but promotes intra-renal adiposity and macrophage infiltration in swine renovascular disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F265–F276, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou FF, Yang Y, Xing D. Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL play important roles in the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. FEBS J 278: 403–413, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu XY, Daghini E, Chade AR, Napoli C, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Simvastatin prevents coronary microvascular remodeling in renovascular hypertensive pigs. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1209–1217, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu XY, Daghini E, Chade AR, Versari D, Krier JD, Textor KB, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Myocardial microvascular function during acute coronary artery stenosis: effect of hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. Cardiovasc Res 83: 371–380, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu XY, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Bentley MD, Chade AR, Sica V, Napoli C, Caplice N, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Antioxidant intervention attenuates myocardial neovascularization in hypercholesterolemia. Circulation 109: 2109–2115, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12: 21–35, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]