Summary

IκB proteins are the primary inhibitors of NF-κB. Here, we demonstrate that sumoylated and phosphorylated IκBα accumulates in the nucleus of keratinocytes and interacts with histones H2A and H4 at the regulatory region of HOX and IRX genes. Chromatin-bound IκBα modulates Polycomb recruitment and imparts their competence to be activated by TNFα. Mutations in the Drosophila IκBα gene cactus enhance the homeotic phenotype of Polycomb mutants, which is not counteracted by mutations in dorsal/NF-κB. Oncogenic transformation of keratinocytes results in cytoplasmic IκBα translocation associated with a massive activation of Hox. Accumulation of cytoplasmic IκBα was found in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) associated with IKK activation and HOX upregulation.

Introduction

NF-κB plays a crucial role in biological processes, such as native and adaptive immune responses, organ development, cell proliferation, apoptosis, or cancer (Naugler and Karin, 2008; Vallabhapurapu and Karin, 2009). NF-κB activation depends on the IKK-mediated degradation of the NF-κB inhibitors, IκB proteins, that takes place in the cytoplasm and results in the translocation of the NF-κB transcription factor to the nucleus, where it activates gene expression. Recent studies demonstrate the existence of alternative nuclear functions for regulatory elements of the pathway (reviewed in Espinosa et al., 2011), but their biological implications remain poorly understood. Recently, it has been demonstrated that nuclear IκBβ binds the promoter of NF-κB target genes following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation to prevent IκBα-mediated inactivation, thereby sustaining cytokine expression in immune cells (Rao et al., 2010). Numerous studies have reported nuclear translocation of IκBα (Aguilera et al., 2004; Arenzana-Seisdedos et al., 1997; Huang and Miyamoto, 2001; Wuerzberger-Davis et al., 2011) and various partners for nuclear IκBα, including histone deacetylases (HDACs) and nuclear corepressors, have been identified (Aguilera et al., 2004; Espinosa et al., 2003; Viatour et al., 2003). In fibroblasts, nuclear IκBα associates with the promoter of Notch target genes correlating with their transcriptional repression, which is reverted by TNFα (Aguilera et al., 2004). Nevertheless, the mechanisms that regulate association of IκB to the chromatin and its repressive function remain unknown.

IκBα-deficient mice die around day 5 because of skin inflammation associated with high levels of IL1β and IFN-γ in the dermis, CD8+ T cells, and Gr-1+ neutrophils infiltrating the epidermis, as well as altered keratinocyte differentiation (Beg et al., 1995; Klement et al., 1996; Rebholz et al., 2007), similar to keratinocyte-specific IκBα-deficient mice (IκBαk5Δ/k5Δ) (Rebholz et al., 2007). In all cases, disruption of TNFα signaling rescued the skin phenotype (Shih et al., 2009), suggesting that lethality was associated with an excessive inflammatory response, likely due to increased NF-κB activity. However, mice expressing different IκBα mutants that are equally able to repress NF-κB in the skin showed divergent phenotypes. Specifically, mice expressing the nondegradable IκBα mutant, IκBαS32-36A, developed skin tumors resembling SCC (van Hogerlinden et al., 1999), whereas mice carrying a predominantly nuclear form of IκBα show no overt skin defects (Wuerzberger-Davis et al., 2011).

Skin differentiation depends on the correct establishment and maintenance of specific gene expression patterns, including genes of the HOX family, which in the basal progenitor cells are repressed by EZH2, the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) (Ezhkova et al., 2009, 2011). PRC2 is composed by EZH2, the WD-repeat protein EED, RbAp48, and the zinc-finger protein SUZ12 (Zhang and Reinberg, 2001). Methylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) by EZH2 imposes gene silencing in part by triggering recruitment of PRC1 (Cao et al., 2002; Min et al., 2003) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). Here, we investigate an alternative function for IκBα in the regulation of skin homeostasis, development, and cancer.

Results

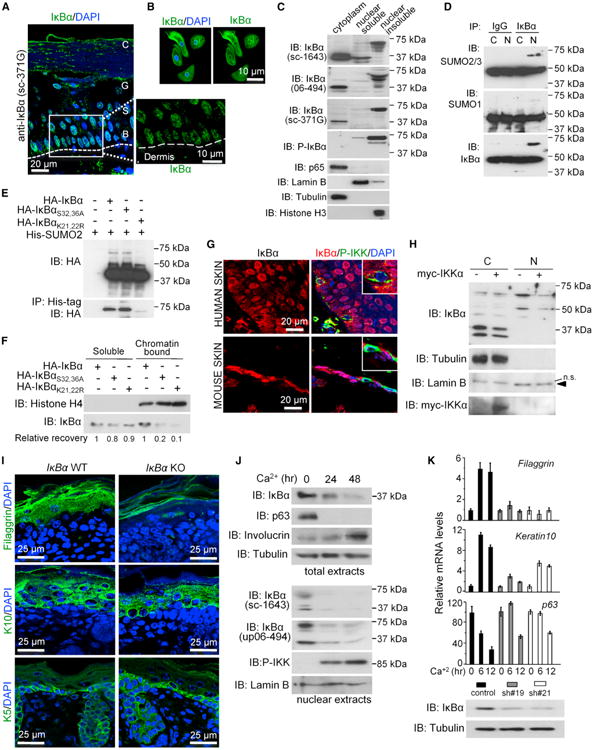

Phosphorylated and Sumoylated IκBα Localizes in the Nucleus of Keratinocytes

To investigate the physiological role for nuclear IκBα, we performed an initial screen to determine its subcellular distribution in human tissues. We found that IκBα localizes in the cytoplasm of most tissues and cell types as expected (Figure S1A available online); yet, a distinctive nuclear staining of IκBα was found in human (Figure 1A) and mouse skin sections (Figures 1A, S1A, and S1C), more prominently in the keratin14+ basal layer keratinocytes. IκBα distribution became more diffused in the supra-basal layer of the skin and gradually disappeared in the more differentiated cells. Specificity of nuclear IκBα staining was confirmed using skin sections from newborn IκBα-knockout (KO) mice (Figure S1B) and different anti-IκBα antibodies and blocking peptides (Figure S1C). By immunofluorescence (IF) and immunoblot (IB), we detected IκBα protein in both the cytoplasmic and the nuclear/chromatin fractions of human (Figures 1B and 1C) and mouse (Figure S1D) keratinocytes. Interestingly, nuclear IκBα displayed a shift in its electrophoretic mobility (≈60 kDa) detected by different anti-IκBα antibodies, including the anti-phospho-S32-36-IκBα antibody. We next precipitated IκBα from nuclear and cytoplasmic keratinocyte extracts and determined whether this low IκBα mobility was a result of ubiquitin or SUMO modifications. We found that nuclear IκBα was specifically recognized by anti-SUMO2/3, but not anti-SUMO1 or anti-ubiquitin antibodies (Figure 1D; data not shown). Hereafter, we will refer to this nuclear IκBα species as phosphoSUMO-IκBα (PS-IκBα). By cotransfection of different SUMO plasmids in HEK293T cells, we demonstrated that SUMO2 was integrated to HA-IκBα at K21,22 (Figure S1E), independently of S32,36 phosphorylation (Figure 1E). By subcellular fractionation, we found that most HA-PS-IκBα was distributed in the nucleus of HEK293T cells (data not shown), and both K21,22R and S32,36A IκBα mutants showed reduced association with the chromatin (Figure 1F). These results suggest that phosphorylation and sumoylation are both required for IκBα nuclear functions in vivo. Of note, PS-IκBα levels were always low in HEK293T cells when compared with keratinocytes, even in overexpression conditions and cell lysates directly obtained under denaturing conditions (see inputs in Figures 1E and S1E).

Figure 1. Phosphorylated and Sumoylated IκBα Is Found in the Nucleus of Normal Basal Keratinocytes.

(A) Immunodetection of IκBα (green) in normal human skin and detail of basal layer. B, basal; S, spinous, G, granular; and C, cornified layers of epidermis. Dashed line indicates the dermis interphase. DAPI was used for nuclear staining.

(B) IF of IκBα in primary human keratinocytes.

(C) Subcellular fractionation of human keratinocytes followed by IB with the indicated antibodies.

(D) IκBα was immunoprecipitated from primary murine keratinocyte extracts followed by IB with the indicated antibodies.

(E) IB analysis of His-tag precipitates from HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids. SUMO2 is incorporated in IκBα when K21,22 are present.

(F) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated IκBα plasmids and processed following the ChIP protocol to obtain the whole chromatin fraction that was analyzed by IB.

(G) IF of IκBα and P-IKK in skin sections. Cells with P-IKK staining do not contain nuclear IκBα.

(H) IB analysis of keratinocytes transduced with myc-IKKαEE or control.

(I) IF analysis of the indicated differentiation markers in skin sections of WT and IκBα KO newborn mice.

(J) IB analysis of indicated proteins in control or Ca2+-treated murine keratinocytes. Total and nuclear/chromatin fractions are shown.

(K) Determination of Filaggrin, K10, and p63 mRNA levels in control and IκBα KD keratinocytes following Ca2+ treatment. Expression levels are relative to Gapdh and compared to control cells. Error bars indicate SD. IκBα protein levels were analyzed by IB. Data correspond to one representative of three experiments. N, nuclear; C, cytoplasmic.

See also Figure S1.

It is well known that IKK activity regulates the cytoplasmic levels of IκBα. By double staining of skin sections, we found that the few cells that were positive for active IKK contained IκBα, but this IκBα was excluded from the nucleus (Figure 1G). To directly investigate whether IKK regulates subcellular distribution of IκBα, we transduced primary murine keratinocytes with lentiviral IKKαEE. We found that active IKKα induced a decrease in the nuclear levels of PS-IκBα as determined by IB (Figure 1H) and IF (Figure S1G). Additional experiments comparing the effects of both IKK isoforms demonstrated that IKKαEE was more efficient than IKKβEE in decreasing nuclear PS-IκBα levels (60% ± 5% compared with 16% ± 9% reduction; p < 0.001) (Figure S1F).

To directly address whether IκBα was required for normal skin differentiation, we performed IF analysis using different markers comparing IκBα wild-type (WT) and KO newborn skins. Consistent with previous reports, IκBα-deficient mice do not show any obvious skin defect at birth with a normal K5-positive basal layer, although we observed a slight reduction in the thickness of the K10-positive suprabasal epidermal layer. Most importantly, IκBα mutant skins showed a severe reduction of the more differentiated layer of cells identified by the accumulation of filaggrin granules (Figure 1I). This is a cause for impaired barrier function (Palmer et al., 2006). Next, we aimed to distinguish between cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous effects of IκBα deficiency by using an in vitro system for keratinocyte differentiation induced by high Ca2+ exposure (Hennings et al., 1980). In this model, we found that keratinocyte differentiation was associated with a decrease in both IκBα and PS-IκBα levels and activation of nuclear IKK (Figures 1J and S1H). Notably, knockdown (KD) of IκBα disturbs in vitro keratinocyte differentiation as indicated by the impaired K10 and filaggrin induction in response to Ca2+, which was accompanied by sustained expression of the progenitor marker p63 (Figure 1K). Together, these results strongly suggest that IκBα plays a cell-autonomous function in skin differentiation.

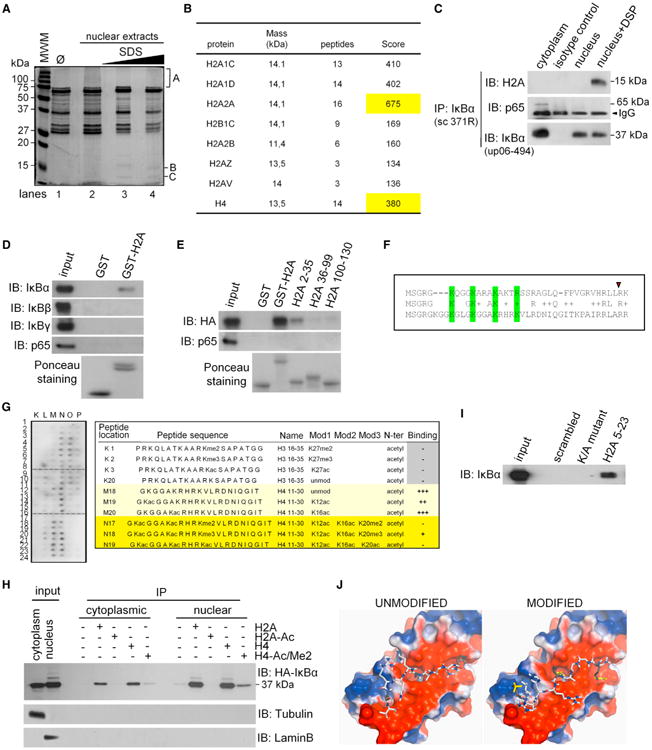

IκBα Directly Binds to the N-Terminal Tail of Histones H2A and H4

To further investigate the mechanisms underlying nuclear IκBα functions, we searched for nuclear proteins that directly associate with IκBα. Using GST-IκBα and human keratinocyte nuclear extracts in pull-down (PD) experiments, we isolated proteins of estimated molecular weights of 15 and 14 kDa that were identified by mass spectrometry as histones H2A and H4 (Figures 2A and 2B). Interaction between histones H2A and H4 and IκBα was further confirmed by coprecipitation of endogenous proteins from keratinocyte nuclear extracts. Of note, the NF-κB subunit p65 was absent from nuclear IκBα precipitates but coprecipitated in the cytoplasmic fraction (Figure 2C). By PD assays, we determined the specificity of IκBα binding compared to other IκB homologs (Figure 2D) and mapped the IκBα-binding domain of histone H2A to be between amino acids 2 and 35 (Figure 2E). Preincubation of IκBα with p65 prevented its association with histones (Figure S2A), suggestive of mutually exclusive complexes.

Figure 2. IκBα Binds Histones H2A and H4.

(A) PD experiment using GST-IκBα and native (lane 2) or denatured-renatured (lanes 3–4) human keratinocyte nuclear extracts. One representative gel stained with Coomassie blue is shown (n = 3).

(B) Purification and analysis of B and C bands identified as histones H2A and H4 by mass spectrometry. Table indicates the number of peptides identified and their score factor. The highest score is highlighted.

(C) Coprecipitation from DSP-crosslinked nuclear extracts from human keratinocytes.

(D and E) PD using different GST-H2A proteins and total lysates from HEK293T cells expressing the indicated proteins.

(F) ClustalW alignment of the conserved KXXXK/R motifs in the N terminus of histones H2A and H4. Conserved K and R residues are in green. Red triangle indicates the last AA included in GST-H2A 2-35.

(G) Histone peptide array hybridized with nuclear HEK293T extracts expressing HA-IκBα. One informative area of the blot image and the relative binding of selected peptides are shown.

(H) Coprecipitation of cytoplasmic and nuclear HA-IκBα expressed in HEK293T cells with the indicated histone H2A and H4 peptides.

(I) HA-IκBα was precipitated using the indicated histone H2A peptide, the K/A mutant, or scrambled peptide. In (G), (H), and (I), cell lysates were denatured-renatured previous to the precipitation to disrupt preformed complexes.

(J) Model for binding of the histone H4 peptide (unmodified or modified) to consecutive ankyrin repeats of IκBα (3KXXXK).

See also Figure S2.

Comparative sequence analysis of the IκBα-binding region of histone H2A (AA1–36) and the homologous region of H4 revealed the presence of a motif (3KXXXK/R) that was absent from other histone and nonhistone proteins (Figure 2F). To further study IκBα binding specificity, we screened a histone peptide array using nuclear HA-IκBα expressed in HEK293T cells as bait. We found that IκBα bound to peptides containing AA11–30 of histone H4, but not the corresponding region of histone H3. Most importantly, binding of IκBα to H4 was prevented by the combination K12/K16Ac and K20Ac or Me2 (Figure 2G). Because the equivalent peptides from histone H2A were not included in the array, we performed parallel precipitation experiments using biotin-tagged peptides (AA5–23) of histone H2A and H4 (Figures 2H and 2I). We found that IκBα association was prevented by K12Ac, K16Ac, and K20me2 of histone H4 or the equivalent modifications of the H2A peptide (Figure 2H) and also when all K/R residues in the 3KXXXK motif were changed into A (Figure 2I). Of note that in these experiments histone-bound HA-IκBα was mostly identified as a nonsumoylated band, which opens the possibility that posttranslation modifications are not essential to mediate this interaction in vitro. However, parallel binding experiments using keratinocyte extracts, PS-IκBα, showed a preferential binding to the histone peptides compared with the cytoplasmic 37 kDa IκBα form (Figure S2B). Together, these results strongly suggest that only PS-IκBα can bind the chromatin, but in HEK293T cells this molecule is then desumoylated in vivo or as a consequence of the experimental processing.

To gain further insights into the molecular basis of IκBα binding to histones, we completed the structure of IκBα obtained from the Protein Data Bank (ID code 1IKN), which lacked part of the ankyrin repeat (AR) 1, using RAPPER (Depristo et al., 2005) and performed docking studies with AutoDock Vina (Trott and Olson, 2010) of the histone H4 peptide, GKGGAKRHRKV, that contains most of the KXXXK domain. Docking calculations showed two deep pockets for K interaction in IκBα located between ARs 1-2 and 2-3 and an additional shallower patch between AR3 and 4. Overall, the peptide bound in a clearly negative region on the IκBα surface (Figure 2J), with higher affinity than the modified peptide that was acetylated in the first and second K residues (K12 and K16). We experimentally validated that ARs of IκBα participate in histone binding because the lκBαΔ55-106 mutant, lacking part of AR1, failed to bind GST-H2A (Figure S2C). Similarly, this association was prevented by 1% deoxycholate (Figure S2D), as described for interactions involving the ARs of IκBα (Baeuerle and Baltimore, 1988; Savinova et al., 2009).

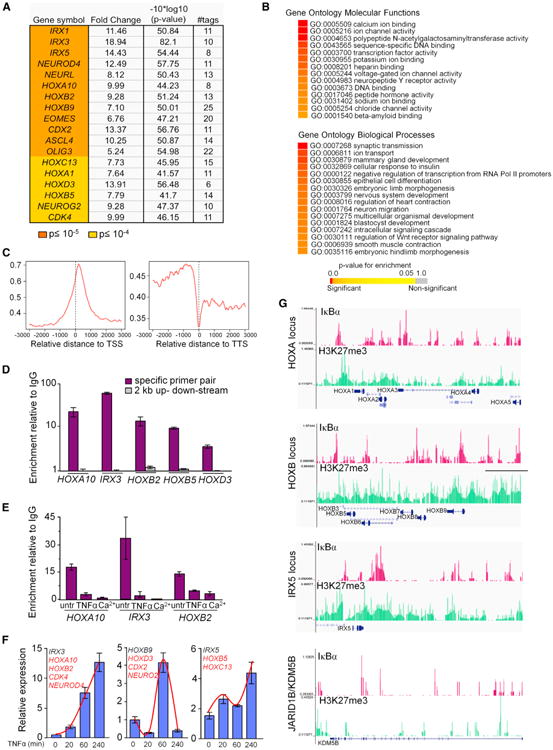

IκBα Is Specifically Recruited to the Regulatory Regions of Developmental Genes

To identify putative PS-IκBα target genes, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) using chromatin extracts from primary human keratinocytes and anti-IκBα antibody. We identified 2,778 enriched peaks, corresponding to 2,433 Ensembl genes that were significantly enriched with p values ≤ 10−5. Gene ontology analysis showed that a significant proportion of genes participate in biological processes associated with embryonic development and cell differentiation. IκBα targets included genes of the HOX and IRX families, ASCL4, CDX2, NEUROD4, OLIG3, and NEURL, among others (Figures 3A and 3B). Annotation of the peak genomic positions to the closest gene demonstrated that many peaks were positioned immediately after the transcription start site (TSS), with a sharp decrease near the transcription termination site (TTS) (Figure 3C), whereas others were located far from promoter regions. Some of the latter overlapped with regions enriched in H3K4me1, a histone mark associated with enhancer regions (data not shown). Randomly selected IκBα targets were confirmed by conventional chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using primers flanking the regions identified in the ChIP-seq experiment (Figure 3D). Consistent with its overall effects on IκBα levels, sustained Ca2+ treatment caused the loss of IκBα from all tested gene promoters (Figure 3E). Similarly, short treatment with TNFα released chromatin-bound IκBα in keratinocytes, as we previously found in fibroblasts (Aguilera et al., 2004). However, we did not detect a general effect of TNFα on PS-IκBα levels, but we consistently found a partial redistribution of PS-IκBα to the soluble nuclear fractions (Figure S3A). Next, we investigated whether TNFα and Ca2+ modulated HOX and IRX transcription in keratinocytes. All tested IκBα targets (n = 12) were robustly induced by TNFα treatment (up to 12-fold) following different kinetics (Figures 3F) and to a lesser extent (up to 3-fold) by Ca2+ treatment (Figure S3B) or IκBα KD (Figure S3C). Interestingly, 1 hr of TNFα treatment prevented Ca2+-induced differentiation of murine keratinocytes (Figure S3D), supporting the notion that PS-IκBα integrates inflammatory signals with skin homeostasis (see Discussion). We also tested whether p65 participated in HOX or IRX gene activation by TNFα. By ChIP analysis, we did not find any recruitment of p65 to IκBα target genes after TNFα treatment, in contrast to a canonical NF-κ;B target gene promoter (Figure S3E). However, we detected low amounts of p65 at HOX genes under basal conditions that might contribute to gene repression (Dong et al., 2008), although the function of chromatin-bound p65 at regions distant from the TSS of both NF-κB targets and nontargets is unresolved. Binding of p65 to HOX and IRX was reduced after TNFα treatment, suggesting that p65 was redistributed from noncanonical to canonical NF-κB targets once activated.

Figure 3. Analysis and Identification of IκBα Target Genes.

(A) Developmentally related genes selected from IκBα targets identified in ChIP-seq analysis. Fold change over the random background is indicated.

(B) Functional enrichment of target genes with p value cutoff ≤ 10−5 based on gene ontology (GO) as extracted from Ensembl database using GiTools. Enriched categories are represented in heatmap with the indicated color-coded p value scale.

(C) Graphs show the relative distance to the nearest ChIPed region, 3 kb upstream and downstream of the RefSeq gene's TSS and TTS.

(D) Validation of the identified DNA regions (−222 to −200 for HOXA10, −9,380 to −9,360 for HOXB2, +6,166 to +6,186 for HOXB5, +4,451 to+4,471 for HOXB3, and −18,820 to −18,800 for IRX3) by conventional ChIP. Amplification of 2 kb distant regions was used as negative controls.

(E) ChIP analysis of IκBα after 20 min of TNFα or 48 hr Ca2+ treatments. In (D) and (E), graphs represent mean enrichment relative to nonspecific immunoglobulin G (IgG) (n = 2).

(F) Expression levels of IκBα target genes following TNFα treatment analyzed by qRT-PCR. Gene represented is in black, whereas genes following the same kinetics are indicated in red.

(G) ChIP-seq profiles of endogenous IκBα occupancy in three enriched loci (HOXA, HOXB, and IRX5) and one negative locus (JARID1B/KDM5B) compared to H3K27me3 (from the UW ENCODE Project) in keratinocytes. (D–F) Bars represent mean, and error bars indicate SD.

See also Figure S3.

Silencing of HOX genes in keratinocytes involves PRC2 and its core component the H3K27 methyltransferase EZH2 (Ezhkova et al., 2009; Mejetta et al., 2011). To explore a putative association between IκBα and PRC2 function, we crossed our list of 2,433 IκBα targets with available ChIP-seq data from keratinocytes. Approximately 50% of IκBα targets corresponded to genes enriched for the H3K27me3 mark (Figures 3G and S3F), although IκBα targeted only 13% of the H3K27 trimethylated genes. Most importantly, genomic sequences occupied by IκBα essentially overlapped with those regions containing high H3K27me3 levels (Figure 3G). We also found a statistically significant overlap (p<10−16) between IκBα target genes and PRC targets in ES cells (Birney et al., 2007; Ku et al., 2008) (Figure S3G).

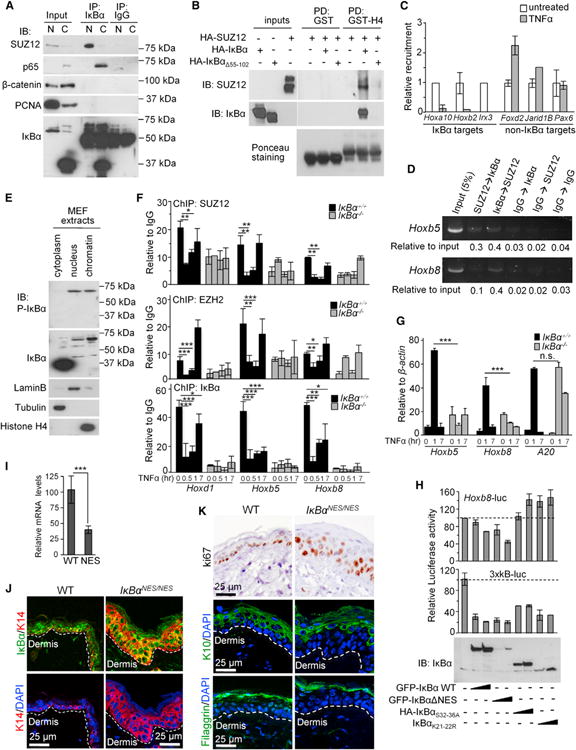

IκBα Interacts with and Regulates Association of PRC2 to Target Genes in Response to TNFα

In the mass spectrometry analysis of proteins that associate with GST-IκBα, we identified a few peptides corresponding to chromatin modifiers, such as EZH2 and SUZ12, and SIN3A (Figure S4A). Specificity of IκBα interactions with PRC2 elements, but also IκBα association to the PRC1 protein BMI1, was confirmed by PD assays (Figure S4B). SUZ12 was able to interact with nuclear IκBα, whereas p65 specifically associated with cytoplasmic IκBα in the IP experiments (Figure 4A). Importantly, exogenous wild-type IκBα, but not an IκBα mutant that failed to bind histones, facilitated the association of SUZ12 to GST-H4 (Figure 4B). Moreover, ChIP experiments demonstrated that TNFα treatment induced the dissociation of SUZ12 from IκBα target regions, but not non-IκBα targets (Figure 4C). Sequential ChIP experiments demonstrated that IκBα and SUZ12 simultaneously bound to IκBα target genes (Figure 4D). To test the functional relevance of IκBα in PRC-mediated repression, we used WT murine embryonic fibroblast (MEFs), which expressed detectable levels of PS-IκBα (Figure 4E) and IκBα KO MEFs. By ChIP-on-chip experiments using three different IκBα antibodies, we confirmed that several Hox genes were also targets of IκBα in MEFs (Table S1). By ChIP, we found that SUZ12 and EZH2 bound IκBα targets efficiently in WT MEFs but only weakly in IκBα KO MEFs (Figure 4F, time 0). In WT cells, TNFα treatment induced a significant but temporary release of SUZ12 and EZH2 from these loci, which peaked after 30– 60 min of treatment (Figure 4F). The binding of PRC2 proteins at Hox genes inversely correlated with the expression of these Hox genes (Figure 4G). In contrast, IκBα KO cells failed to activate Hox transcription in response to TNFα (Figure 4G), which is consistent with a defective release of PRC2 proteins (Figure 4F). Unexpectedly, we did not detect changes in H3K27me3 levels in these Hox genes upon TNFα treatment at any of the time points studied (20 min, 2 hr, and 7 hr) (data not shown), likely reflecting the high stability of this histone modification (De Santa et al., 2007). Supporting the possibility that activation of IκBα targets is independent of the enzymatic activity of EZH2, a 24 hr treatment with the EZH2 inhibitor DZNep does not affect Hoxb8 or Irx3 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels in keratinocytes (data not shown). Together, these results suggest that transcriptional repression-activation of these genes does not strictly depend on EZH2 enzymatic activity but rather PRC2 release might modulate the dissociation of PRC1 or HDACs (van der Vlag and Otte, 1999) that associate with more dynamic chromatin modifications. In agreement with this possibility, histone H3 is rapidly acetylated following TNFα treatment at different Hox gene promoters (Figure S4C).

Figure 4. IκBα Interacts with and Regulates Association of PRC2 in Response to TNFα.

(A) IB analysis of IκBα precipitates from nuclear and cytoplasmic primary murine keratinocyte extracts. Five percent of the input and 25% of the IP was loaded in all cases except for detection of IκBα input that represents 0.5%.

(B) PD using GST-H4 and cell lysates from HEK293T expressing different combinations of HA-IκBα and SUZ12.

(C) Relative recruitment assessed by ChIP of SUZ12 to different genes 40 min after TNFα in primary murine keratinocytes.

(D) Sequential ChIP using the indicated combinations of antibodies. An analysis of two different Hox regulatory regions is shown.

(E) IB analysis of WT fibroblasts showing the presence of cytoplasmic and nuclear IκBα.

(F) Relative chromatin binding of PRC2 and IκBα in WT and IκBα KO MEFs treated with TNFα. ChIP values were normalized by IgG precipitation.

(G) Relative levels of the indicated genes in WT and IκBα KO MEFs.

(H) Luciferase assays to determine the effect of different IκBα constructs on the activity of HoxB8 compared to the 3xκB reporter. Lower panels show expression levels of different constructs.

(I) Expression levels of HoxB8 in the skin of WT and IκBαNES/NES mice by qRT-PCR (n = 2).

(J and K) Analysis of skin sections from 7- to 8-week-old WT and IκBαNES/NES mice by IF. K14 labels the basal layer keratinocytes (J). Immunostaining of ki67, the suprabasal marker K10, and filaggrin (K). Throughout the figure, bars represent mean, and error bars indicate SD.

See also Figure S4 and Table S1.

To further study the involvement of NF-κB in the regulation of IκBα targets by TNFα, we attempted to use different mutant MEFs, including the p65, Ikkα, Ikkβ, and the triple p65;p50;c-Rel KO. We found that TNFα induced Hox and Irx expression in both p65 and Ikkβ KO cells (Figure S4D) suggesting that it was NF-κB independent. However, specific mutants contained variable levels of IκBα and PS-IκBα (Figures S4E and S4F), which make a more accurate quantitative analysis unproductive. Interestingly, phosphorylation of nuclear IκBα was not reduced in the Ikkα or Ikkβ KO cells (Figures S4F), indicating that other kinases are involved in generating PS-IκBα. Only triple KO cells, which essentially lacked IκBα (Figure S4G) and the Ikkα-deficient MEFs, showed a strong defect on Hox and Irx transcription (Figures S4D and S4H). To better understand the contribution of NF-κB to Hox regulation, we next performed luciferase reporter assays measuring the ability of different IκBα mutant proteins to repress a Hoxb8-promoter construct compared with a reporter containing three consensus sites for NF-κB (3xκB). We found that WT IκBα and the nuclear IκBαNES mutant (Huang et al., 2000) significantly repressed both promoters. However, mutations that affect chromatin-association (Figure 1F) prevented Hoxb8 repression but still inhibited the expression of the 3×κB reporter (Figure 4H). Consistently, Hoxb8 mRNA levels were significantly reduced in the skin of mice expressing IκBαNES (Wuerzberger-Davis et al., 2011) (Figure 4I). Moreover, these animals showed an expansion of the K14-positive basal layer of keratinocytes containing nuclear IκBα (Figure 4J), associated with increased proliferation measured by ki67 staining and impaired differentiation as indicated by the reduced thickness of the suprabasal K10-expressing layer (Figure 4K).

Genetic Interaction between IκBα/cactus and polycomb in Drosophila

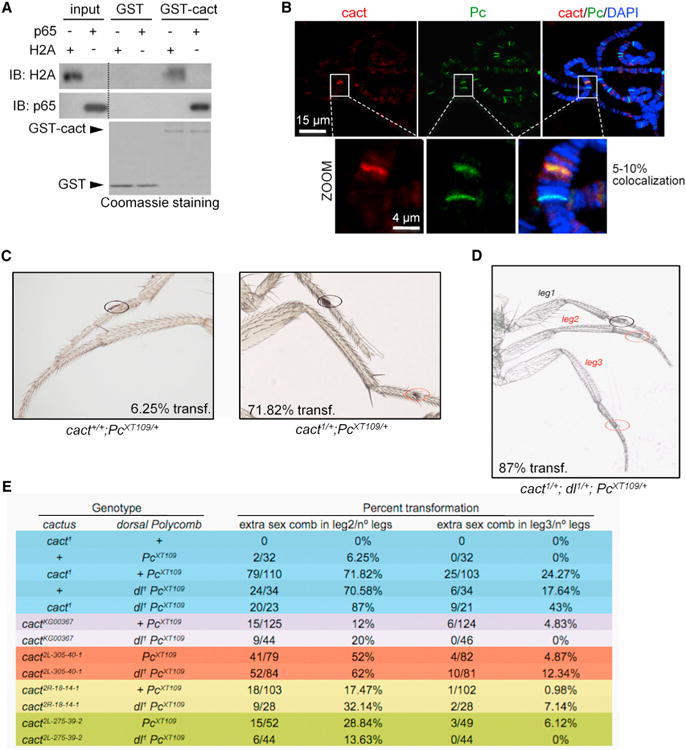

Polycomb group (PcG) IκB and NF-κB proteins are conserved from flies to humans. In addition, Drosophila contains one Hox cluster, compared with four clusters in vertebrates, which facilitates studying genetic interactions. We first confirmed that the single Drosophila IκB homolog, cactus (cact) (Geisler et al., 1992), maintained the capacity to associate with histones (Figure 5A). By IF, we detected colocalization of cactus and Polycomb (Pc), a PRC1 protein that is essential for the repressive PRC2 function, in specific bands of polytene chromosomes (Figure 5B). Most of the cactus staining overlapped with Pc, but only a few Pc-positive bands contained cactus. Based on our mammalian data, our first attempt was to generate single PRC2 mutants and combine them with cactus-deficient mutants. All mutants were tested in heterozygosis because homozygous mutations in cactus or PcG genes are lethal.

Figure 5. Mutations in cactus/IκBα Enhances the Homeotic Phenotype of Heterozygous Pc Mutants in Drosophila melanogaster.

(A) PD using GST-cactus and detection of p65 expressed in HEK293T or H2A from a histone-enriched extract.

(B) Representative image of a double IF for cact and Pc in Drosophila salivary polytene chromosomes. Selected region is shown in the magnification. cact-positive bands always overlap Pc staining.

(C) The percent of mutant adults with “extra sex comb” in legs 2 and 3 (red circles) was measured in at least 100 legs of flies heterozygous for 12 cact mutations in two different Pc−/+ mutant backgrounds.

(D) Representative image of the homeotic phenotype induced by cact in Pc mutants, which is enhanced by heterozygous mutation of dorsal. In (C) and (D), the percentage of flies with “extra sex combs” in leg 2 is indicated.

(E) Frequency of the homeotic phenotypes corresponding to the number of “extra sex combs” in second and third leg in flies with the indicated cactus, dorsal, and Polycomb mutations.

See also Tables S2 and S3.

We found that heterozygous mutations in PRC2 genes (e.g., the null mutations of E(z)) as well as the composed E(z) and cact exhibit no overt homeotic phenotypes. In contrast, heterozygous Pc mutants exhibit a variety of characteristic homeotic transformations, including the partial transformation of the second and third (mesothoracic and metathoracic) legs toward first (also known as prothoracic) legs that in males are characterized by the presence of sex combs. Modifications of this phenotype (also called “extra sex comb”) have been extensively used as a functional assay to validate new PcG proteins in vivo. Thus, we tested the effect of reducing cact on Pc-induced homeotic transformation using 12 recessive mutations of cact and two independently generated Pc alleles. All cact mutant alleles, but more prominently cact1, enhanced the “extra sex comb” phenotype of Pc mutations (Pc3 and PcXT109) (Figure 5C; Table S2).

Because cells lacking cact exhibit massive nuclear localization of the transcription factor dorsal (dl, Drosophila NF-κB/Rel/p65 ortholog) during postembryonic stages (Lemaitre et al., 1995), we tested whether enhancement of homeotic defect of Pc by cact mutations is due to increased dorsal activity. Because stability of cact is under NF-κB/Dorsal control (Kubota and Gay, 1995), we anticipated that for phenotypes due to increased dorsal, dl mutations would counteract cact mutations, whereas for phenotypes independent of dorsal, reducing dl should yield phenotypes similar to that of cact mutants. We found that heterozygous dl mutations significantly enhanced the extra sex comb transformation phenotype of Pc heterozygotes (Table S3), similar to the effect of cact mutations. Furthermore, by generating triple heterozygous strains carrying the null allele of dorsal (dl1), the PcXT109 allele and different cact alleles, we found that most of the triple heterozygous cact;dl;Pc exhibited similar or stronger homeotic phenotypes than double heterozygotes for dl;Pc and cact;Pc of a particular allelic combination (Figures 5D and 5E). Note that the smaller number of animals scored in the triple heterozygotes also reflects the higher lethality of this genotype. These data support our finding that IκB/cactus cooperates with Polycomb-mediated repression, independently of NF-κB/dorsal, which is relevant for the regulation of epidermal development in the fly.

Requirement of IκBα for Keratinocyte Transformation and HOX Upregulation

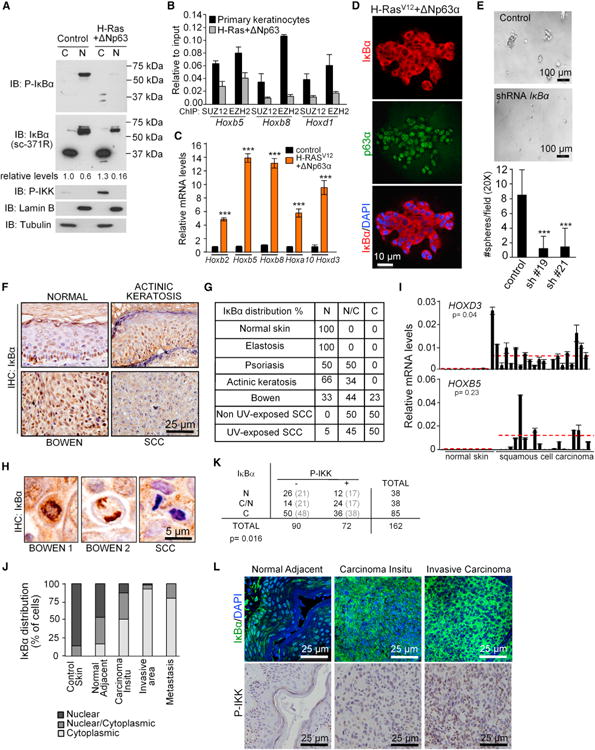

Deregulated HOX expression is a common trait in cancer (De Souza Setubal Destro et al., 2010; Hassan et al., 2006; Yamatoji et al., 2010; Zhai et al., 2007), including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). To study whether IκBα participates in Hox deregulation of SCC, we induced transformation of primary murine keratinocytes by expressing mutant H-RasV12 plus ΔNp63α using retroviral infection (Keyes et al., 2011). We found that PS-IκBα, which was consistently detected in the nuclear fraction of control-transduced keratinocytes, was mainly lost in transduced cells associated with P-IKK induction (Figure 6A). By ChIP assay, we found that binding of SUZ12 and EZH2 at IκBα targets was significantly decreased in these cells (Figure 6B), concomitant with a massive increase in IκBα target gene expression (Figure 6C). Furthermore, transformed keratinocytes growing in three-dimensional (3D) matrigel cultures showed a complete cytoplasmic distribution of IκBα (Figure 6D), whereas IκBα KD abrogated the capacity of transformed keratinocytes to grow in matrigel (Figure 6E), similar to the nontransformed cells. These results suggest that accumulation of cytoplasmic IκBα favors oncogenic transformation.

Figure 6. IκBα Accumulates in the Cytoplasm after Keratinocyte Transformation Associated with Hox Induction.

(A) IB analysis of IκBα in the subcellular fractions of primary and H-Ras/ΔNp63α transformed keratinocytes.

(B) ChIP analysis of PRC2 recruitment on the indicated genes in control and transformed keratinocytes.

(C) Expression levels of the indicated genes relative to Gapdh.

(D) IF of IκBα in the transformed keratinocytes growing in 3D cultures.

(E) Transformation capacity of H-Ras/ΔNp63α transduced keratinocytes in control or IκBα KD cells. Image of 3Dcultures (upper panels) and graph represents the number of spheres from 5 × 103 cells after 5 days in culture (lower panel). Sixteen fields (20×) from two independent experiments were counted.

(F and G) Analysis by immunohistochemistry of IκBα distribution in different human skin lesions. (G) Table indicates the percent of nuclear (N), diffuse (N/C), or cytoplasmic (C) distribution in the analyzed samples.

(H) Chromosomal localization of IκBα in mitotic cells from Bowen's disease samples, but not in SCC cells.

(I) Expression analysis of the indicated genes by qRT-PCR. Red line indicates the mean expression in normal and SCC samples. Significance of the differences was determined using Student's t test analysis.

(J) IκBα distribution in control and different grades of tumor progression in a collection of 112 human urogenital SCC samples.

(K) Correlation between subcellular distribution of IκBα and P-IKK levels in this group of patients. Statistical significance of the association was determined by a chi-square test.

(L) Representative images showing IκBα and P-IKK staining indifferent lesions from the same patient. In(C) and (E) ***p < 0.001, as determined by Student's t test analysis. In (B), (C), (E), and (I), bars represent mean, and error bars indicate SD.

We further explored this possibility by analyzing the subcellular distribution of IκBα protein in a tissue microarray (TMA) that included different human nonmalignant or premalignant skin lesions (n = 21), skin cancer (n = 32), and normal control samples (n = 3). We detected nuclear IκBα in different nonmalignant/noninflammatory lesions and normal skin samples. In noninvasive tumors, such as actinic keratosis and Bowen's disease, a variable proportion of cells displayed localization of IκBα in the cytoplasm, but most of them retained nuclear IκBα, including chromosomal staining of the mitotic keratinocytes (Figure 6H). In more aggressive cutaneous SCC, around 50% of the tumor cells showed a complete loss of nuclear IκBα and accumulation of cytoplasmic IκBα (Figures 6F and 6G). By qRT-PCR, we measured the mRNA levels of several IκBα targets in 21 SCC and 13 normal skin samples. We found that HOXD3 was significantly increased in human SCC compared with normal skin (p = 0.04). We also detected a consistent upregulation of HOXB9 and HOXB5 that did not reach statistical significance due to the dispersion between samples (Figure 6I; data not shown).

We extended our study to a cohort of 112 patients with urogenital SCC at different stages of tumor progression. We found that cytoplasmic IκBα accumulation started before the stage of tumor invasion, but total loss of nuclear IκBα was most predominant in the invasive areas of the tumors and in the metastases. The significance of the correlations was p < 0.0001 for normal adjacent versus in situ tumor, p < 0.0001 for in situ compared with infiltrating tumors, and p = 0.3 when comparing the tumor with the metastasis, using the Fisher's exact test (Figures 6J and 6L). Cytoplasmic accumulation of IκBα significantly associated with IKKα activation in these samples (Figures 6K and 6L).

Discussion

Here, we show that IκBα plays a function in the chromatin associated with repression of developmental genes, including the HOX and IRX families. We focused our study on the skin keratinocytes, where we found a significant accumulation of nuclear IκBα; however, this mechanism is not exclusive of this cell type and operates at least also in fibroblasts. In addition, we deciphered part of the mechanism of IκBα-mediated repression that involves posttranslational IκBα modifications and association with histones H2A/H4 and Polycomb proteins. The evolutionary conservation of this mechanism is illustrated by the strong homeotic phenotype of double Polycomb and cactus mutants in Drosophila.

Compiled data on NF-κB signaling demonstrate that IκBα plays a major role as inhibitor of the p65/p50 dimer and termination of NF-κB signal after stimulation. In the latter, establishment of a nuclear IκBα-NF-κB transient ternary complex actively facilitates dissociation of NF-κB from specific binding sites in the DNA (Zabel and Baeuerle, 1990), leading to the notion that IκBα and chromatin binding are irreconcilable. Our experiments demonstrate that a specific fraction of IκBα that is phosphorylated at S32,36 and posttranslationally modified by SUMO2 at K21,22 is able to bind the histones. Sumoylation of IκBα had been previously described, but the functional relevance of this modification was mainly unknown (Desterro et al., 1998). Although phosphorylation of S32,36 is the instructive mark that targets IκBα for K21,22 ubiquitination and its subsequent degradation by the proteasome, we now propose that K21,22 sumoylation protects phosphorylated IκBα from degradation, thus generating an unexpected functional IκBα species. Whether calcium-induced degradation of PS-IκBα involves its desumoylation and subsequent ubiquitylation, and which modifications in both IκBα and histones are imposed by TNFα and induce PS-IκBα release from the chromatin, is currently under investigation.

Our data suggest that other IκB homologs cannot compensate IκBα chromatin function because Hoxb5 and Hoxb8 failed to be induced by TNFα in IκBα KO cells. However, expression of IκBβ from the IκBα locus compensates most of the defects of IκBα deficiency (Cheng et al., 1998), which suggest that a specific fraction of IκBβ (i.e., hypophosphorylated nuclear IκBβ) might overlap nuclear IκBα functions in the skin or that ectopic IκBβ affects regulation of cytokines that mediate lethality in IκBα KO models (Rebholz et al., 2007). It is the strong association between inflammation and the skin phenotype that has impaired distinguishing between cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous effects of IκBα deletion on keratinocyte differentiation. Our data indicate that IκBα plays an essential role in this process, as shown by the strong decrease in the number of Filaggrin-expressing cells in the skin of IκBα KO newborn mice, which results in a defective skin barrier that might explain the massive inflammatory response observed in these animals after cytokine exposure. Moreover, this function is cell autonomous as indicated by our in vitro data. However, in transformed keratinocytes and human SCC, IκBα is accumulated in the cytoplasm associated with tumor progression and increased HOX expression, which is consistent with the tumorigenic phenotype of mice expressing the chromatin binding-defective IκBα super-repressor mutant in the skin (Dajee et al., 2003; van Hogerlinden et al., 1999, 2004). We propose that accumulation of IκBα in the cytoplasm, or even in the nucleoplasm as it is observed after TNFα exposure, contributes to gene activation by sequestering nuclear repressors. In contrast, knockin mice carrying a nuclear IκBα mutant do not show defective skin function or signs of SCC, even in aged mice (data not shown). Although we cannot exclude the involvement of NF-κB in the IκBα mutant phenotypes, these reports and our data support the concept that nuclear IκBα through Hox/Irx regulation might provide a platform to integrate control of barrier integrity with cytokine response, while preventing cell transformation.

On the other hand, extensive in silico analysis of the IκBα target promoters failed to reveal any enrichment of specific sequences that could mediate binding specificity, which is coherent with the absence of known DNA elements that recognize PRC2 in mammalian genes and is different from Drosophila genes that contain PRE elements (Simon et al., 1993). Instead, our data show that IκBα binds the chromatin in regions enriched for H3K27me3, which is antagonized by specific combinations of histone H2A/H4 modifications. Such H2A/H4 modifications are involved in skin differentiation (Frye et al., 2007) and are known to regulate chromatin structure (Kimura et al., 2002; Shogren-Knaak et al., 2006; Suka et al., 2002), which could be connected with the IκBα function described here.

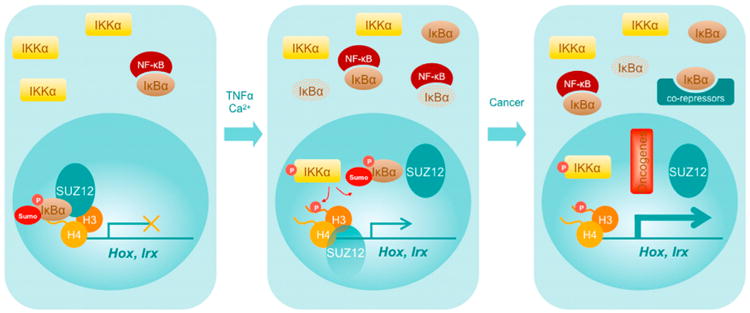

Based on our results, we propose a model (Figure 7) in which nuclear PS-IκBα negatively regulates transcription of developmentally related genes in collaboration with Polycomb proteins. Keratinocyte differentiation or TNFα treatment result in the loss of chromatin-associated IκBα and Polycomb release, associated with a moderate or temporary activation of Hox and Irx transcription, respectively. Upon oncogenic transformation, nuclear IκBα is lost, but it accumulates in the cytoplasm, leading to a massive activation of Hox and Irx genes, likely related with cytoplasmic retention of negative regulators of gene transcription (Aguilera et al., 2004; Viatour et al., 2003). Future studies will focus on establishing the exact histone code that is recognized by IκBα and the elements involved in its regulation, both in physiological and pathological situations.

Figure 7. Model for Nuclear IκBα Function in Normal and Transformed Cells.

In brief, sumoylated and phosphorylated IκBα binds the chromatin of noninduced and nontransformed cells to maintain gene repression, which is relieved after cytokine induction or keratinocyte transformation. Release of IκBα from the chromatin is, at least in part, mediated by IKKα and results in PRC dissociation and specific gene activation. These effects are maximized by stimuli that lead to tumorigenesis.

Experimental Procedures

Tissue Samples

Human tissue samples were obtained from the archive of the Pathology Department of the Hospital del Mar with the consent of Bank Tumor Committee, following Spanish Ethical regulations and guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient identity remained anonymous. Mouse samples were obtained from pathogen-free mice colonies that included C57Bl6/J, CD1, IκBα-deficient (Beg et al., 1995), and IκBαNES/NES mice (Wuerzberger-Davis et al., 2011). The Animal Care Committee of Generalitat de Catalunya, USCD and University of Wisconsin approved all procedures.

Cell Fractionation

Cells were lysed in 10 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, and 0.05% NP40at pH 7.9 for 10 min on ice and spun at 3,000 rpm. Supernatants were the cytoplasmic fraction. Pellets were lysed in 5 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, and 26% glycerol at pH 7.9, sonicated 5 s three times, left on ice 20 min, and then centrifuged 15 min at 13,000 rpm to recover the soluble nuclear fractions. Pellets included the non-soluble chromatin-enriched fraction.

Coimmunoprecipitation Assay and Peptide Array

For precipitation of nuclear extracts, nuclei were either crosslinked with dithiobis succinimidyl propionate (DSP, Pierce) 15 min at room temperature and then sonicated in a bioruptor (Diagenode) in 1% SDS-containing buffer and then neutralized by 1% Triton X-100, or directly sonicated in RIPA buffer plus protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 10 mM N-ethyl maleimide. In both cases, nuclear lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min and then incubated with 5 μg of the indicated antibodies. Precipitates were captured with 35 ml of protein A-sepharose, extensively washed, and analyzed by IB. In most of the experiments, we used the Clean-Blot IP Detection Kit instead of standard secondary antibodies, which is optimized for postimmunoprecipitation IB.

Histone peptides were synthesized as biotinylated N-terminal and C-terminal amides (Peptides and Elephants). Peptides were incubated overnight at 4°C with the indicated cell extracts and precipitated with streptavidin-sepharose beads (Amersham) for 45 min. Denatured HEK293T nuclear extracts were used to hybridize a histone peptide array from Active Motif (N.13001). Peptide composition can be found at http://www.activemotif.com/catalog/667/histone-peptide-array and includes different combinations of acetylated, methylated, or unmodified peptides.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation, ChIP-on-Chip, and ChIP-Seq

Cells were subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) as previously described (Aguilera et al., 2004). Briefly, formaldehyde crosslinked cell extracts were sonicated, and chromatin fractions were incubated with sc-371, sc-371G, sc-1643 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or 06-494 (Upstate) anti-lκBα antibodies in RIPA buffer and precipitated with protein A/G-sepharose (Amersham). Crosslinkage was reversed, and DNA was analyzed by PCR, sequenced, or labeled to hybridize the Mouse BCBC PromoterChip 5 from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/EPConDB/). Data obtained were analyzed with AFM 4.0 software (Breitkreutz et al., 2001). Anti-IκBα antibody 06-494 (Upstate) was used for ChIP-seq, and 6 ng of precipitated chromatin from human keratinocytes was directly sequenced in these experiments. Data are deposited at the GEO database with accession numbers GSM744581 and GSE24011. For mapping, peak calling, and functional enrichment analysis, see the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Up to now, the only known function for IκBα is as a repressor of NF-κB. We now demonstrate that IκBα plays an alternative role in the chromatin through binding to histones H2A and H4 and regulation of polycomb-dependent transcriptional repression. Consistent with the functional relevance of polycomb-associated IκBα function, Cactus/IκBα deficiency affects Drosophila development. In mammals, we found that IκBα regulates keratinocyte differentiation and transformation associated with altered Hox/IRX expression.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Sumoy, D. Otero, and J. Lozano from the CRG Microarray Service for the analysis of ChIP-on-chip data and the Proteomics and Genomics facilities at PRBB. We also thank M. Karin and G. Ghosh from UCSD and F. Meijlink from the Hubrech Laboratory for valuable reagents, A. Mas, R. Viñas, S. Cuartero, M.L. Espinàs, G. Marfany, R. García, J. Bertran, C. Rius, F. Torres, and J. Inglés-Esteve for experimental and technical support, and B. Alsina, S. Aznar Benitah, and all members of the lab for helpful discussions. M.M. is an investigator of the Sara Borrell program (CD09/00421). E.L.A. is a recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from the Department of Education, Universities and Research of the Basque Government (BFI-2011), and V.R. was a recipient of FIMIM predoctoral fellowship. L.E. is an investigator at the Carlos III program. This work was supported by a grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI041890), Fundación Mutua Madrileña, AGAUR (SGR23), and RTICCS/FEDER (RD06/0020/0098 and RD12/0036/0054). M.D. was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (BFU2009-09074 and MEC-CONSOLIDER CSD2007-00023), Generalitat Valenciana (PROMETEO 2008/134), and a grant from European Union Research (UE-HEALH-F2-2008-201666). J.V-F. was funded by a MICINN grant (CTQ2008-00755) and the EC VPH (no. FP7-2007-IST-223920).

Footnotes

Accession Numbers: The GEO accession number for the ChIP-on-chip and ChIP-seq reported in this paper are GSM744581 and GSE24011, respectively.

Supplemental Information: includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, four figures, and three tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2013.06.003.

References

- Aguilera C, Hoya-Arias R, Haegeman G, Espinosa L, Bigas A. Recruitment of IkappaBalpha to the hes1 promoter is associated with transcriptional repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16537–16542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404429101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Turpin P, Rodriguez M, Thomas D, Hay RT, Virelizier JL, Dargemont C. Nuclear localization of I kappa B alpha promotes active transport of NF-kappa B from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:369–378. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. I kappa B: a specific inhibitor of the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Science. 1988;242:540–546. doi: 10.1126/science.3140380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg AA, Sha WC, Bronson RT, Baltimore D. Constitutive NF-kappa B activation, enhanced granulopoiesis, and neonatal lethality in I kappa B alpha-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2736–2746. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, Guigó R, Gingeras TR, Margulies EH, Weng Z, Snyder M, Dermitzakis ET, Thurman RE, et al. ENCODE Project Consortium; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center; Washington University Genome Sequencing Center; Broad Institute; Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitkreutz BJ, Jorgensen P, Breitkreutz A, Tyers M. AFM 4.0: a toolbox for DNA microarray analysis. Genome Biol. 2001;2 doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-8-software0001. SOFTWARE0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R, Wang L, Wang H, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science. 2002;298:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1076997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JD, Ryseck RP, Attar RM, Dambach D, Bravo R. Functional redundancy of the nuclear factor kappa B inhibitors I kappa B alpha and I kappa B beta. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1055–1062. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dajee M, Lazarov M, Zhang JY, Cai T, Green CL, Russell AJ, Marinkovich MP, Tao S, Lin Q, Kubo Y, Khavari PA. NF-kappaB blockade and oncogenic Ras trigger invasive human epidermal neoplasia. Nature. 2003;421:639–643. doi: 10.1038/nature01283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santa F, Totaro MG, Prosperini E, Notarbartolo S, Testa G, Natoli G. The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing. Cell. 2007;130:1083–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza Setubal Destro MF, Bitu CC, Zecchin KG, Graner E, Lopes MA, Kowalski LP, Coletta RD. Overexpression of HOXB7 homeobox gene in oral cancer induces cellular proliferation and is associated with poor prognosis. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:141–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depristo MA, de Bakker PI, Johnson RJ, Blundell TL. Crystallographic refinement by knowledge-based exploration of complex energy landscapes. Structure. 2005;13:1311–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desterro JM, Rodriguez MS, Hay RT. SUMO-1 modification of IkappaBalpha inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell. 1998;2:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Jimi E, Zhong H, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Repression of gene expression by unphosphorylated NF-kappaB p65 through epigenetic mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1159–1173. doi: 10.1101/gad.1657408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa L, Inglés-Esteve J, Robert-Moreno A, Bigas A. IkappaBalpha and p65 regulate the cytoplasmic shuttling of nuclear corepressors: cross-talk between Notch and NFkappaB pathways. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:491–502. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa L, Bigas A, Mulero MC. Alternative nuclear functions for NF-κB family members. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:446–459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezhkova E, Pasolli HA, Parker JS, Stokes N, Su IH, Hannon G, Tarakhovsky A, Fuchs E. Ezh2 orchestrates gene expression for the stepwise differentiation of tissue-specific stem cells. Cell. 2009;136:1122–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezhkova E, Lien WH, Stokes N, Pasolli HA, Silva JM, Fuchs E. EZH1 and EZH2 cogovern histone H3K27 trimethylation and are essential for hair follicle homeostasis and wound repair. Genes Dev. 2011;25:485–498. doi: 10.1101/gad.2019811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye M, Fisher AG, Watt FM. Epidermal stem cells are defined by global histone modifications that are altered by Myc-induced differentiation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler R, Bergmann A, Hiromi Y, Nüsslein-Volhard C. cactus, a gene involved in dorsoventral pattern formation of Drosophila, is related to the I kappa B gene family of vertebrates. Cell. 1992;71:613–621. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan NM, Hamada J, Murai T, Seino A, Takahashi Y, Tada M, Zhang X, Kashiwazaki H, Yamazaki Y, Inoue N, Moriuchi T. Aberrant expression of HOX genes in oral dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma tissues. Oncol Res. 2006;16:217–224. doi: 10.3727/000000006783981080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennings H, Michael D, Cheng C, Steinert P, Holbrook K, Yuspa SH. Calcium regulation of growth and differentiation of mouse epidermal cells in culture. Cell. 1980;19:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TT, Miyamoto S. Postrepression activation of NF-kappaB requires the amino-terminal nuclear export signal specific to IkappaBalpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4737–4747. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4737-4747.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TT, Kudo N, Yoshida M, Miyamoto S. A nuclear export signal in the N-terminal regulatory domain of IkappaBalpha controls cytoplasmic localization of inactive NF-kappaB/IkappaBalpha complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1014–1019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes WM, Pecoraro M, Aranda V, Vernersson-Lindahl E, Li W, Vogel H, Guo X, Garcia EL, Michurina TV, Enikolopov G, et al. ΔNp63α is an oncogene that targets chromatin remodeler Lsh to drive skin stem cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A, Umehara T, Horikoshi M. Chromosomal gradient of histone acetylation established by Sas2p and Sir2p functions as a shield against gene silencing. Nat Genet. 2002;32:370–377. doi: 10.1038/ng993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klement JF, Rice NR, Car BD, Abbondanzo SJ, Powers GD, Bhatt PH, Chen CH, Rosen CA, Stewart CL. IkappaBalpha deficiency results in a sustained NF-kappaB response and severe widespread dermatitis in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2341–2349. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku M, Koche RP, Rheinbay E, Mendenhall EM, Endoh M, Mikkelsen TS, Presser A, Nusbaum C, Xie X, Chi AS, et al. Genomewide analysis of PRC1 and PRC2 occupancy identifies two classes of bivalent domains. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K, Gay NJ. The dorsal protein enhances the biosynthesis and stability of the Drosophila I kappa B homologue cactus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3111–3118. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B, Meister M, Govind S, Georgel P, Steward R, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. Functional analysis and regulation of nuclear import of dorsal during the immune response in Drosophila. EMBO J. 1995;14:536–545. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejetta S, Morey L, Pascual G, Kuebler B, Mysliwiec MR, Lee Y, Shiekhattar R, Di Croce L, Benitah SA. Jarid2 regulates mouse epidermal stem cell activation and differentiation. EMBO J. 2011;30:3635–3646. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min J, Zhang Y, Xu RM. Structural basis for specific binding of Polycomb chromodomain to histone H3 methylated at Lys 27. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1823–1828. doi: 10.1101/gad.269603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naugler WE, Karin M. NF-kappaB and cancer-identifying targets and mechanisms. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CN, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Zhao Y, Liao H, Lee SP, Goudie DR, Sandilands A, Campbell LE, Smith FJ, et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:441–446. doi: 10.1038/ng1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao P, Hayden MS, Long M, Scott ML, West AP, Zhang D, Oeckinghaus A, Lynch C, Hoffmann A, Baltimore D, Ghosh S. IkappaBbeta acts to inhibit and activate gene expression during the inflammatory response. Nature. 2010;466:1115–1119. doi: 10.1038/nature09283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebholz B, Haase I, Eckelt B, Paxian S, Flaig MJ, Ghoreschi K, Nedospasov SA, Mailhammer R, Debey-Pascher S, Schultze JL, et al. Crosstalk between keratinocytes and adaptive immune cells in an IkappaBalpha protein-mediated inflammatory disease of the skin. Immunity. 2007;27:296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savinova OV, Hoffmann A, Ghosh G. The Nfkb1 and Nfkb2 proteins p105 and p100 function as the core of high-molecular-weight heterogeneous complexes. Mol Cell. 2009;34:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih VF, Kearns JD, Basak S, Savinova OV, Ghosh G, Hoffmann A. Kinetic control of negative feedback regulators of NF-kappaB/RelA determines their pathogen- and cytokine-receptor signaling specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9619–9624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812367106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shogren-Knaak M, Ishii H, Sun JM, Pazin MJ, Davie JR, Peterson CL. Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science. 2006;311:844–847. doi: 10.1126/science.1124000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J, Chiang A, Bender W, Shimell MJ, O'Connor M. Elements of the Drosophila bithorax complex that mediate repression by Polycomb group products. Dev Biol. 1993;158:131–144. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suka N, Luo K, Grunstein M. Sir2p and Sas2p opposingly regulate acetylation of yeast histone H4 lysine16 and spreading of heterochromatin. Nat Genet. 2002;32:378–383. doi: 10.1038/ng1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M. Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:693–733. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vlag J, Otte AP. Transcriptional repression mediated by the human polycomb-group protein EED involves histone deacetylation. Nat Genet. 1999;23:474–478. doi: 10.1038/70602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hogerlinden M, Rozell BL, Ahrlund-Richter L, Toftgård R. Squamous cell carcinomas and increased apoptosis in skin with inhibited Rel/nuclear factor-kappaB signaling. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3299–3303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hogerlinden M, Rozell BL, Toftgård R, Sundberg JP. Characterization of the progressive skin disease and inflammatory cell infiltrate in mice with inhibited NF-kappaB signaling. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viatour P, Legrand-Poels S, van Lint C, Warnier M, Merville MP, Gielen J, Piette J, Bours V, Chariot A. Cytoplasmic IkappaBalpha increases NF-kappaB-independent transcription through binding to histone deacetylase (HDAC) 1 and HDAC3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46541–46548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuerzberger-Davis SM, Chen Y, Yang DT, Kearns JD, Bates PW, Lynch C, Ladell NC, Yu M, Podd A, Zeng H, et al. Nuclear export of the NF-κB inhibitor IκBα is required for proper B cell and secondary lymphoid tissue formation. Immunity. 2011;34:188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamatoji M, Kasamatsu A, Yamano Y, Sakuma K, Ogoshi K, Iyoda M, Shinozuka K, Ogawara K, Takiguchi Y, Shiiba M, et al. State of homeobox A10 expression as a putative prognostic marker for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel U, Baeuerle PA. Purified human I kappa B can rapidly dissociate the complex of the NF-kappa B transcription factor with its cognate DNA. Cell. 1990;61:255–265. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90806-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y, Kuick R, Nan B, Ota I, Weiss SJ, Trimble CL, Fearon ER, Cho KR. Gene expression analysis of preinvasive and invasive cervical squamous cell carcinomas identifies HOXC10 as a key mediator of invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10163–10172. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Reinberg D. Transcription regulation by histone methylation: interplay between different covalent modifications of the core histone tails. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2343–2360. doi: 10.1101/gad.927301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.