Abstract

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) detached from both primary and metastatic lesions represent a potential alternative to invasive biopsies as a source of tumor tissue for the detection, characterization and monitoring of cancers. Here we report a simple yet effective strategy for capturing CTCs without using capture antibodies. Our method uniquely utilized the differential adhesion preference of cancer cells to nanorough surfaces when compared to normal blood cells and thus did not depend on their physical size or surface protein expression, a significant advantage as compared to other existing CTC capture techniques.

Keywords: Cancer, circulating tumor cell, nanotopography, biomaterials, microfabrication

Over the last decade, there has been great interest in utilizing peripheral blood circulating tumor cells (CTCs) to predict response to therapy and overall survival of patients with overt or incipient metastatic cancers.1-2 CTCs are shed by both primary and metastatic lesions and they are thought to contribute to hematogenous spread of cancer to distant sites.3-4 It has been demonstrated that the presence of elevated CTC levels is negatively correlated with prognosis in patients with metastases of the breast, prostate, lung, and colon.5-6 Despite the clinical and pathophysiological importance of CTCs, the current molecular and cellular understanding of CTCs is extremely poor, largely due to the fact that the current techniques to isolate and characterize these rare cells are limited by low yield and purity, complex techniques, and expensive proprietary equipments, compounded by the currently employed techniques yielding little phenotypic and molecular information about the CTCs themselves.7-8

So far, different approaches have been used to isolate CTCs, which can be divided into two groups: cell size-based isolation using membrane filters or microfluidic sieves9-11 and immunoaffinity purification using immunomagnetic beads1,12 or microfluidic chips2,13-18 conjugated with antibodies against surface markers of cancer cells. Even though these approaches have been used to demonstrate the presence of CTCs in patients with metastatic cancer, each of these approaches has intrinsic major limitations. Briefly, size-based separation of CTCs is hampered by the fact that CTCs are not universally larger than all leukocytes and leukocytes clot filter pores or are collected along with CTCs thereby contaminating the isolate. For immunoaffinity purification, a monoclonal antibody against the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) is most commonly used because of its nearly universal expression on cells of epithelial origin and its absence from blood cells. However, surface expression of EpCAM on CTCs might be more heterogeneous than initially anticipated (e.g., due to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition) and even absent altogether in some tumor types (such as melanoma).19-20 Thus, positive isolation and enrichment of CTCs based on their EpCAM expression can potentially result in a substantial loss of informative CTCs.21-22 To avoid the biases of selecting cells based on their EpCAM expression alone, immunoaffinity-based negative depletion methods to remove CD45+ leukocytes and thereby enrich residual CTCs have also been employed.23-24 Although this strategy has the potential to purify CTCs regardless of cancer cell surface markers, the extremely low prevalence of CTCs can significantly limit the yields of purified CTC fractions achieved by negative selection.23-24

Herein, by taking advantage of the differential adhesion preference of cancer cells to nanorough surfaces when compared to normal blood cells, we report a simple, yet effective strategy for capturing CTCs regardless of their physical size and without using any capture antibody. To this end, we have recently developed a simple yet precisely-controlled method to generate random nanoroughness on glass surfaces using reactive ion etching (RIE)25 (see Experimental Section; Fig. 1A&B). RIE-based nanoscale roughening of glass surfaces is consistent with a process of ion-enhanced chemical reaction and physical sputtering.26 In our previous work, we had shown that bare glass surfaces treated with RIE for different periods of time could acquire different levels of roughness (as characterized by the root-mean-square roughness Rq; Rq = 1 - 150 nm) with a nanoscale resolution.25 Integrating RIE with photolithography, spatially patterned nanorough islands could be generated on glass surfaces. Thus, by precisely controlling both techniques, photolithography and RIE, we could specify the location, shape, area, and nanoroughness levels of different nanorough regions on glass surfaces (Fig. S1A). In this work, we successfully demonstrated that our RIE-generated nanorough surfaces could efficiently capture different kinds of cancer cells (i.e., MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, Hela, PC3, SUM-149) without using any capture antibody. Our cancer cell capture strategy with the nanorough glass surface uniquely utilized the differential adhesion preference of cancer cells to nanorough surfaces when compared to normal blood cells, and thus it did not depend on the cancer cells’ physical size or surface protein expression, a significant advantage as compared to other existing CTC capture techniques.

Figure 1.

Intrinsic nanotopological sensing for capture of cancer cells. (A&B) Schematic of nanotopography generated by RIE on glass surfaces. Inserts show a zoom-in (left) and a SEM (right) images of cancer cells captured on nanorough glass surfaces. (C) SEM images of glass surfaces with their RMS nanoroughness indicated. (D-G) Cancer cells spiked in growth media at a concentration of 105 mL-1captured on glass surfaces 1 hr after cell seeding. D shows fluorescence images of MCF-7 cells captured on glass surfaces coated with (bottom) or without (top) EpCAM antibodies. MCF-7 cells were stained for nuclei (DAPI; green) for visualization and enumeration. E-G plotted capture yields of MCF-7 (E), MDA-MB-231 (F), and other cancer cell lines (G) as a function of nanoroughness. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m; n = 4).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Differential Adhesion Preference of Cancer Cells to Nanorough Surfaces

Using RIE-generated nanorough glass surfaces, we first examined the differential adherence preference of cancer cells to nanorough glass surfaces. Two breast cancer cell lines, MCF-7 (EpCAM-positive, or EpCAM+) and MDA-MB-231 (EpCAM-negative, or EpCAM-) were seeded as single cells on a glass surface patterned with nanorough islands or letters (Rq = 70 nm). Phase-contrast images of cancer cells taken 24 hrs after cell seeding showed both cell types adhering selectively to patterned nanorough regions (Fig. S1A). Quantitative analysis revealed that adhesion selectivity, defined as the ratio of the number of cells adhered to nanorough regions and the total number of cells attached to the whole glass surface, was 96.1% and 95.2% for MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, respectively (Fig. S1B), suggesting strong segregation of cancer cells for adherance to nanorough surfaces, regardless of their EpCAM expression status. We further performed the EdU proliferation assay for cancer cells, and our data suggested that proliferation rate of cancer cells increased with nanoroughness (Fig. S1C).

Effcient Capture of Cancer Cells without Using Capture Antibodies

To examine specifically whether the RIE-generated nanorough glass surfaces could achieve efficient capture of cancer cells without using any capture protein bait, we prepared two sets of unpatterned nanorough glass surfaces: one coated with anti-EpCAM antibody and the other unprocessed. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells spiked in 500 μL growth media were seeded at a concentration of 105 cells mL-1 on nanorough glass surfaces. After different periods of incubation (0.5 - 8 hrs), glass samples were rinsed gently to remove floating cells, and the remaining adherent cells were stained with DAPI for visulization and enumeration (Fig. 1D & Fig. S2A). Cancer cell capture yield, defined as the ratio of the number of cancer cells captured on glass surfaces to the total number of cells initially seeded, was quantified as a function of both incubation time and nanoroughness Rq. Our results in Fig. S2 and Fig. 1D-F revealed significant enhancements of cancer cell capture yield and speed by nanorough surfaces, and such improvements appeared to increase with nanoroughness Rq but were independent of anti-EpCAM antibody coating. For example, bare uncoated nanorough glass surfaces with Rq = 150 nm captured 80% MCF-7 and 73% MDA-MB-231 cells within 1 hr of cell incubation. In distinct contrast, only 14% MCF-7 and 10% MDA-MB231 cells were captured on bare smooth glass surfaces (Rq = 1 nm) over the same period of time. Importantly, the contribution to additional cancer cell capture using anti-EpCAM antibody coating was relatively insignificant, especially when Rq > 50 nm (Fig. 1E-F). We further performed capture assays using other cancer cell lines, including Hela cervical cancer cells, PC3 prostate cancer cells, and SUM-149 inflammatory breast cancer cells, and similar significant enhancements of cancer cell capture yield and speed by nanorough surfaces were observed (Fig. 1G). Taken together, our results demonstrated that RIE-generated nanoroughness on glass surfaces enhances cancer cell capture yield up to 80% within 1 hr of cell incubation, regardless of EpCAM expression on cancer cell surfaces and without using any capture antibody coating.

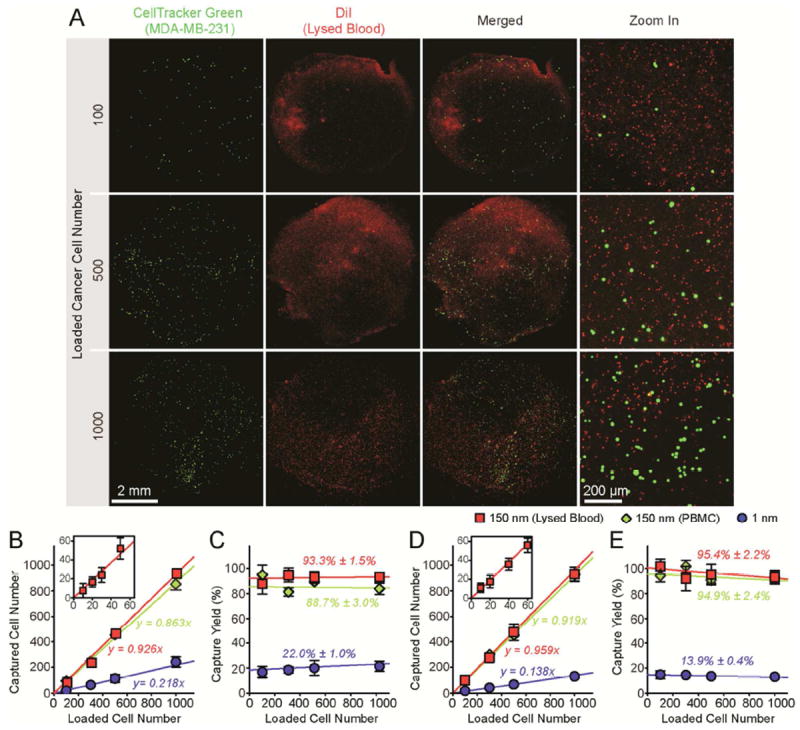

To evaluate the efficiency of our RIE-generated nanorough substrates for capturing rare CTCs from blood specimens without using capture antibody, we conducted capture assays for known quantities of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (n = 10 - 1,000) spiked in 500 μL culture media containing peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs; cancer cells mixed with PBMCs at a constant ratio of 1:1) (Fig. S3) or 500 μL lysed human blood (Fig. 2). Target cancer cells and background cells (PBMCs or leukocytes in lysed blood) were first labeled with CellTracker Green and Δ9-DiI, respectively, before they were mixed and used for 1-hr cell capture assays with nanorough glass surfaces (Rq = 150 nm). As shown in Fig. 2, high capture yields were achieved with nanorough glass surfaces for both EpCAM+ MCF-7 and EpCAM- MDA-MB-231 cells, even at low cancer cell concentrations and for both PBMC and lysed blood samples (Fig. 2B-E). On average, capture yields were 88.7% ± 3.0% and 93.3% ± 1.5% for MCF-7 cells mixed with PBMCs and spiked in lysed blood, respectively (Fig. 2B&C), while for MD-MB-231 cells, capture yields were 94.9% ± 2.4% and 95.4% ± 2.2% for the PBMC and lysed blood samples, respectively (Fig. 2D&E). In contrast, control experiments using smooth glass substrates (Rq = 1 nm) with cancer cells spiked in culture media showed much lower capture yields for both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (22.0% ± 1.0% for MCF-7 and 13.9% ± 0.4% for MDA-MB-231) (Fig. 2B-E), again confirming the efficiency of nanorough substrates for capturing cancer cells.

Figure 2.

Capture and enumeration of cancer cells. (A) Representative fluorescence and merged microscopic images showing known quantities of MDA-MB-231 cells as indicated spiked in lysed blood captured on nanorough glass surfaces (Rq = 150 nm) 1 hr after cell seeding. Target MDA-MB-231 cells were labeled with CellTracker Green before spiked in lysed blood that was pre-stained with DiI. (B-E) Regression analysis of 1-hr capture efficiency for MCF-7 (B&C) and MDA-MB-231 (D&E) cells on smooth (Rq = 1 nm) and nanorough (Rq = 150 nm) glass surfaces. In A-E, known quantities of cancer cells (n = 10 - 1,000) were spiked in 500 mL growth media containing PBMCs or 500 mL lysed blood as indicated. For PBMC samples, cancer cells were mixed with PBMCs at a constant ratio of 1:1. Insets in B&D show correlations between captured cell number and loaded cell number for n = 10 - 60, indicating efficient capture of low abundant CTCs. Solid lines represent linear fitting. Error bars represent ± s.e.m. (n = 4).

We further studied systematically the effect of admixtures of cancer cells with other background cells on the efficiency and purity of cancer cell capture on uncoated nanorough glass surfaces (Rq = 150 nm) by varying the ratio of MDA-MB-231 and PBMCs from 1:1 to 1:200, with the MDA-MB-231 cell number fixed at 1,000 (Fig. 3A). Our 1-hr cell capture assay results in Fig. 3 showed that capture yields of MDA-MB-231 were preserved with admixture and were as high as 93.6%. Thus, the capture yield was not affected strongly by the proportion of background PBMCs (Fig. 3B&C). Interestingly, capture yields of PBMCs by uncoated nanorough glass surfces remianed low and were gradually decreased from 16.7% to 4.1% when the ratio of MDA-MB-231 and PBMCs decreased from 1:1 to 1:200 (Fig. 3C). Not surprisingly, as the absolute numbers of PBMCs captured on nanorough glass surfaces increased when the ratio of MDA-MB-231 and PBMCs decreased from 1:1 to 1:200, capture purity of MDA-MB-231 cells was significantly decreased from 84% to 14% (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Effect of cellular background on capture yield and purity of cancer cells. (A) Fluorescence and merged microscopic images showing CellTracker Green-labeled MDA-MB-231 cells and DiI-stained PBMCs captured on nanorough glass surfaces (Rq = 150 nm) 1 hr after cell seeding. The ratio of cancer cells and PBMCs was varied as indicated. (B-D) Captured cell number (B), capture yield (C) and purity (D) of MDA-MB-231 cells on nanorough glass surfaces (Rq = 150 nm) as a function of the ratio of MDA-MB-231 cells to PBMCs. Results were obtained 1 hr after cell seeding. In A-D, a fixed number of cancer cells (1,000) were mixed with PBMCs in growth media to achieve cell ratios from 1:1 to 1:200. Error bars represent ± s.e.m. (n = 4).

Cell Adhesion Strength Measurements

Our results in Fig. 2 & Fig. 3 showed a significantly different levels of preference between cancer cells and PBMCs to adhere to nanorough glass surfces, which suggested an interesting possibility that adhesion strength of cancer cells might be affected by nanotopographic sensing, while adhesion of PBMCs might not be sensitive to nanotopographic cues. To examine this possibility, we developed a microfluidic channel using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) integrated with smooth (Rq = 1 nm) or nanorough (Rq = 100 nm) glass substrates for direct measurements of adhesion strength of cancer cells and PBMCs (see Experimental Section; Fig. 4A & Fig. S4).27 A low density of cancer cells (MCF-7, MBA-MB-231 and PC3 cells) or PBMCs was seeded uniformly inside the microfluidic channel for 12 hrs before they were exposed to constant directional fluid shear (0.1 - 120 dyne cm-2) for 5 min. We quantified fractions of cancer cells and PBMCs remained adherent on smooth and nanorough substrates after their treatments with this sustained 5-min directional fluid shear.28 Our data demonstrated that indeed, cancer cells attached on nanorough surfaces could withstand much greater fluidic shear stress than on the smooth surface, regardless of EpCAM expression on cancer cell surfaces (Fig. 4B-D & Fig. S4). Adhesion strength of cancer cells, defined as the fluidic shear stress at which 50% of cancer cells initially attached on glass surfaces would detach after exposed to fluid shear for 5 min,29 was significantly greater for cancer cells adhering on the nanorough surface than the smooth one (Fig. 4F). As expected, adhesion strength of PBMCs to both smooth and nanorough glass surfaces was low, and they could easily be washed away even under a shear stress < 1 dyne cm-2, consistent with our observation that most PBMCs were still floating on both smooth and nanorough glass surfaces even after 12 hrs of incubation (data not shown). Measurements of adhesion strength of cancer cells and PBMCs after 1 hr of incubation had been difficult, as most cells were still floating and not attach to glass surfaces, likely attributable to the confined microfluidic environment. Together, our results in Fig. 5 demonstrated that nanotopographic surfaces could significantly enhance adhesion strength of cancer cells, regardless of their EpCAM expression. Adhesion of PBMCs to uncoated glass surfaces appeared to be not sensitive to nanotopographic cues.

Figure 4.

Effect of nanotopological sensing on cell adhesion strength. (A) Schematic of a microfluidic channel integrated with smooth or nanorough glass substrates for quantifications of cell adhesion strength. Insert shows adherent cancer cells in the channel under sustained directional fluid shear. (B-E) Fraction of MCF-7 (B), MBA-MB-231 (C), PC3 (D) and PBMCs (E) remained adherent on smooth (Rq = 1 nm) or nanorough (Rq = 100 nm) substrates after 5-min exposures to sustained directional fluid shear. Low densities of cancer cells or PBMCs were seeded into microfluidic channels and cultured for 12 hrs before PBS was flowed continuously along the channel to exert fluid shear stress on cells. (F) Adhesion strength of MCF-7, MBA-MB-231 and PC3 cells on smooth (Rq = 1 nm) or nanorough (Rq = 100 nm) substrates. Solid lines in B-E represent logistic (B-D) or exponential (E) fitting to guide eyes. Error bars represent ± s.e.m. (n = 4). Statistical analysis was performed by employing the Student’s t-test. ** indicates p < 0.01.

Figure 5.

Effect of nanotopological sensing on focal adhesion (FA) formation of MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of MDA-MB-231 cells adherent on smooth (Rq = 1 nm) and nanorough (Rq = 100 nm) glass surfaces after 24 hr of culture. Cells were co-stained for nuclei (DAPI; blue), actin (red), and vinculin (green). (B-E) Cell area (B), total FA area per cell (C), average single FA area (D) and number of FAs per cell area (FA density; E) of MDA-MB-231 cells adherent on smooth (Rq = 1 nm) and nanorough (Rq = 100 nm) glass surfaces after 24 hr of culture. Error bars represent ± s.e.m. (n > 30). Statistical analysis was performed by employing the Student’s t-test. ** indicates p < 0.01.

Nanotopological Sensing through Focal Adhesions

To investigate the possible mechanotransductive mechanism for nanotopographic sensing of cancer cells, we examined focal adhesions (FAs) of EpCAM+ MCF-7 and EpCAM- MDA-MB-231 cells plated as single cells on both smooth and nanorough glass surfaces. Published data indicate that integrin-mediated FA signaling, critical for many cellular functions and strongly dependent on their nanoscale molecular arrangement and dynamic organization, may play an important role in regulating cellular mechanosensitivity to nanotopography.30 After 24 hrs in culture, both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells exhibited distinct FA formation and organization on the smooth and nanorough glass surfaces, as characterized by immunofluorescence staining of vinculin, a FA protein (Fig. 5 & Fig. S5). On smooth glass surfaces where Rq = 1 nm, mature and prominent vinculin-containing FAs formed primarily on the periphery of both cancer cells. By comparison, on nanorough surfaces with Rq = 150 nm, both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells exhibited randomly distributed, punctate FAs of small cross-sections throughout the entire cell spread area. Morphometric analysis of cell populations showed that on nanorough glass surfaces, both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells had smaller mean cell spread area and single FA area and less total number of FAs and total FA area per cell than on the smooth surface (Fig. 5B-E & Fig. S5B-E). The molecular arrangement and dynamic organization of integrin-mediated FAs of both cancer cells appeared sensitive and responsive to local presentation of nanotopographical cue and hence might result in their distinct adhesion behaviors on nanorough surfaces as demonstrated in this work.

CONCLUSION

In summary, here we report for the first time a simple yet effective strategy for highly sensitive and specific capture of different types of cancer cells using RIE-generated nanorough glass surfaces. Our cancer cell capture strategy uniquely utilized the differential adhesion preference of cancer cells to nanorough surfaces when compared to normal blood cells and thus did not depend on their physical size or surface protein expression, a significant advantage as compared to other existing CTC capture techniques. Previous studies have reported different micro- and nanostructured surfaces for capture of CTCs;14-15 however, to achieve efficient capture of CTCs, these surfaces still require functionalization with capture proteins to recognize cancer cells.

Given the vast phenotypic differences between MCF7, MDA-231, and PC3, we surmise that our cancer cell capture strategy is very likely to be applicable to many different cancer cell types and can potentially provide a promising solution to study intratumor phenotypic heterogeneity at the single-cell level using patient CTCs for diagnostics and therapy.31-32 In spite of the strong adhesion preference of cancer cells for our RIE-generated nanorough surfaces, the capture purity achieved so far with nanorough glass surfaces is still suboptimal. Our future efforts will be directed toward integrating nanorough glass surfaces with microfluidic components such as chaotic mixers to improve both capture yield and purity for CTCs. Exploiting the differential adhesion preference of cancer cells for nanorough surfaces when compared to normal blood cells is a promising strategy to achieve their efficient capture at very low costs and is expected to lead to better isolation and enrichment strategies for live CTCs from cancer patient’s blood specimens, critical for informative analysis of CTCs and for accurate diagnosis, therapeutic choices, and prognosis and for fundamental understanding of cancer metastasis.

METHODS

Fabrication of Nanorough Glass Samples

For patterned nanorough glass samples, photoresist was first spin-coated on glass wafers (Borofloat 33, Plan Optik, Elsoff, Germany) and patterned using photolithography. The glass wafer was then processed with RIE (LAM 9400, Lam Research, Fremont, CA) for different periods of time to generate nanoscale surface roughness (ranging from 1 nm to 150 nm) on the open regions of the glass wafer, where the photoresist had previously been developed and dissolved. The RIE process condition was selected as: SF6 (8 sccm), C4F8 (50 sccm), He (50 sccm), Ar (50 sccm), chamber pressure (1.33 Pa), bias voltage (100 V), and radio frequency power (500 W), with the resulting glass etch rate as about 50 nm/min. After the RIE process, photoresist was striped using solvents, and the glass wafer was cleaned using distilled water. For unpatterned nanorough glass samples, bare glass wafers were directly processed with RIE under the same RIE condition as described above. The glass wafers were then cut into small pieces (1.5 cm × 1.5 cm) using the ADT7100 dicing saw (Advanced Dicing Technologies Ltd., Yokneam, Israel). Before assays with cells, every glass sample was bonded to a 1-cm thick PDMS structure that had a circular opening (diameter 6 mm) at its center using vacuum grease (Dow Corning Corp., Midland, MI).

Surface Characterization Using Atomic Force Microscope

Nanoroughness of the glass surfaces was measured at room temperature with the Veeco NanoMan Atomic Force Microscope (AFM, Digital Instruments Inc., Santa Barbara, CA) using a non-contact, tapping mode and standard Si tapping mode AFM tips with a scan rate of 1 Hz. The resulting map of the local surface height was represented using AFM topographs. The nanoroughness of each glass sample was characterized by the root mean square (RMS) roughness Rq of the local surface height over the scanned areas collected using the AFM topographs.

Cell Culture and Reagents

Hela and MCF-7 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in growth media consisting of high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biological, Atlanta, GA), 0.5 μg mL-1 Fungizone (Invitrogen), 5 μg mL-1 Gentamicin (Invitrogen), 100 units mL-1 penicillin, and 100 μg mL-1 streptomycin. PC-3 and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in growth media (RPMI-1640, ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biological), 0.5 μg mL-1 Fungizone (Invitrogen), 5 μg mL-1 Gentamicin (Invitrogen), 100 units mL-1 penicillin, and 100 μg mL-1 streptomycin. SUM149 cells were cultured in growth media (Ham’s F-12 w/L-glutamine, Fisher Scientific, Hanover Park, IL) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biological), 0.5 μg mL-1 Fungizone (Invitrogen), 5 μg mL-1 Gentamicin (Invitrogen), 5 μg mL-1 Insulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 1 μg mL-1 Hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 units mL-1 penicillin, and 50 μg mL-1 streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 100% humidity. Fresh 0.25% trypsin-EDTA in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was used to re-suspend cells.

Anti-EpCAM Antibody Coating

Glass Surfaces were functionalized with anti-EpCAM antibodies using avidin-biotin chemistry. Briefly, glass substrates were first treated with O2 plasma for 1-2 min and modified with 4% (v/v) 3-mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane (Sigma-Aldrich) in ethanol at room temperature for 30-45 min. After rinsed with ethanol, the glass surfaces were treated with N-ymaleimidobutyryloxy succinimide ester (GMBS, 1 mM or 0.28%; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) in ethanol for 15 min. After rinsed with PBS, the glass surfaces were treated with 10 μg/ml Neutravidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS at room temperature for 30 min, leading to immobilization of Neutravidin onto GMBS. The glass surfaces were rinsed with PBS to remove excess free avidin. Finally, biotinylated anti-EpCAM antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml in PBS with 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA; Equitech-Bio Inc, Kerrville, TX) and 0.09% (w/v) sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the glass samples for 15-30 min. The glass substrates were washed with PBS, air dried and stored at ambient temperature for up to three weeks till later use.

Human Blood Specimen Collection and Processing

Human blood specimens were obtained from healthy donors and collected into EDTA-contained vacutainer according to a standard protocol. Human blood specimens were processed and assayed within 6 hr after collection. To lyse blood, RBC Lysis Buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) was added to whole blood at a 10:1 v/v ratio. After incubation for 10 min at room temperature, the Lysis Buffer was diluted with 20-30 mL PBS to stop the reaction. Then the solution was centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min to remove supernatant. The cell pellet was re-suspended in an equivalent volume of cell growth medium, before the sample was used for capture assays.

SEM Specimen Preparation

Cell samples were washed three times with 50 mM Na-cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3; Sigma-Aldrich), fixed for 1 hr with 2% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in 50 mM Na-cacodylate buffer, and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol concentrations through 100% over a period of 1.5 hr. Dehydration in 100% ethanol was performed three times. Afterwards, dehydrated substrates were dried with liquid CO2 using a super critical point dryer (Samdri®-PVT-3D, Tousimis, Rockville, MD). Samples were mounted on stubs, sputtered with gold palladium, observed and photographed under a Hitachi SU8000 Ultra-High Resolution SEM machine (Hitachi High Technologies America, Inc., Pleasanton, CA).

Immunofluorescence Staining of Focal Adhesions

In brief, cells were incubated in an ice-cold cytoskeleton buffer (50 mM NaCl, 150 mM sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 μg mL-1 aprotinin, 1 μg mL-1 leupeptin, and 1 μg mL-1 pepstatin) for 1 min and then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) in the cytoskeleton buffer for 1 min. Detergent-extracted cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in PBS for 30 min and washed three times with PBS. Fixed cells were then incubated with 10% goat serum (Invitrogen) for 1 hr, and then incubated with a primary antibody to vinculin produced in mouse (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hr, and stained with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 hr. Alexa Fluor 555 conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen) and DAPI were used to visualize F-actin and nucleus, respectively.

Quantitative Analysis of Cell Spread Area and Focal Adhesion

Immunofluorescence images of actin cytoskeleton and vinculin were obtained using the Carl Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope equipped with the AxioCam camera (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY) and a 40× objective (1.3 NA, oil immersion; EC Plan NEOFLUAR). Images were captured using the Axiovision Software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) and processed using custom-developed MATLAB programs (Mathworks, Natick, MA). To determine spread area of each cell, the Canny edge detection method was used to binarize actin fibers and FAs, and then image dilation, erosion, and fill operations were used to fill in gaps between white pixels. The resultant white pixels were summed to quantify cell area. To quantify FA number and area for each cell, the grayscale vinculin image was thresholded to produce a black and white FA image from which the white pixels, representing FAs, were counted and summed.

EdU Cell Proliferation Assay

MDA-MB-231 cells were first starved at confluence in the growth medium supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum (Invitrogen) for 48 hr to synchronize cell cycle before trypsinization. Synchronized cells were re-plated on glass substrates and recovered in the complete growth medium for 12 to 24 hr, and were then exposed to 4 μM 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU; Invitrogen) in the growth medium for 9 hr. Cells were then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Science) in PBS, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, blocked with 10% goat serum, and stained with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated azide targeting alkyne groups in EdU that was incorporated in newly synthesized DNA. Cells were co-stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) to visualize cell nucleus.

Quantification of Capture Yields of Cancer Cells

Prior to cell capture assays, targeted cancer cells were labeled with CellTracker Green (Invitrogen) before they were mixed with Δ9-DiI (Invitrogen)-stained background cells (PBMCs or leukocytes in lysed blood). The total cell number in each sample was first determined using a hemocytometer, and the desired cell concentration was then prepared by serially diluting the original cell suspension with fresh culture media. The cell suspenssions were then loaded onto PDMS microwells (with a diameter of 6 mm) assembled onto the nanrough glass surfaces. After incubation at 5% CO2 and 37°C for different durations (0.5-8 hr), the glass samples were rinsed gently with PBS to remove floating cells. The adherent substrate-immobilized cells were then imaged using fluorescence microscopy (Nikon Eclipse Ti-S, Nikon, Melville, NY) equipped with an electron multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD) camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Specially, sequential brightfield and fluorescent images were taken using a 10× (Ph1 ADL, numerical aperture or N.A. = 0.25, Nikon) objective. To quantify cancer cell capture yield and purity, the whole surface area of glass samples was scanned on a motorized stage (ProScan III, Prior Scientific, Rockland, MA). The images obtained from scanning were stitched using microscopic analysis software (NIS-Element BR, Nikon). Image processing software ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was then used to determine the number of cells attached to glass surfaces.

Fabrication of PDMS Microfluidic Channels for Cell Adhesion Strength Measurements

The PDMS microfluidic channel was fabricated using soft lithography and replica molding. Briefly, a silicon master for microfluidic channels was fabricated using photolithography and deep reactive ion etching (DRIE; STS Deep Silicon Etcher, Surface Technology Systems, Newport, UK). The silicon master was then silanized with (tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2,-tetrahydrooctyl)-1-trichlorosilane vapor (United Chemical Technologies, Bristol, PA) for 4 hrs under vacuum to facilitate subsequent release of the PDMS microfluidic channel from the silicon master. PDMS prepolymer (Sylgard 184, Dow-Corning, Midland, MI) was then prepared by thoroughly mixing the monomer with the curing agent (with the w/w ratio of 10:1), poured onto the silicon master and cured at 110 °C for 30 min. Fully cured PDMS channel was peeled off from the silicon mold, and the excessive PDMS was trimmed using a razor blade. The PDMS microfluidic channel used in this study had a channel width W of 2 mm, a channel total length L of 6 mm, and a channel height H of 80 μm. For the smooth (Rq = 1 nm) glass substrate, the PDMS microfluidic channel was bound to the glass substrate using the oxygen plasma-assisted bonding process. For nanorough glass substrates, a device holder composed of two pieces of polyacrylate plates was home-machined to sandwich the PDMS channel and the nanorough glass substrate using screws at the four corners of the polyacrylate plates. Two through-holes were drilled on the top polyacrylate plate to align with the inlet and outlet holes of the PDMS microfluidic channel, thus allowing a convenience connection of tubings to the microfluidic channel. The complete assembly using polyacrylate plates to hold the PDMS microfluidic channel could endure a back pressure of about 50 psi without leaking.

Cell Adhesion Strength Measurements

To measure cell adhesion strength, cancer cells (MCF-7, MBA-MB-231 or PC3 cells) in growth media were first injected into the microfluidic channel by pipette and the cells were allowed to adhere to the bottom glass substrate in an incubator for 12 hrs. An optimized cell loading density (1 × 106 cells mL-1) was used to ensure a uniform seeding of single cells on the substrate. The microfluidic channel was then connected to a syringe pump, and a constant flow of PBS was injected into the channel to exert directional fluid shear stress on cells. To remove floating cells before cell adhesion strength measurements, PBS was flowed into the channel with a very low flow rate (10 μL min-1 for 1 min, then 30 μL min-1 for 1 min). Then the flow rate was increased to a designated value (50-1500 μL min-1) and maintained constant for 5 min to exert a constant directional fluid shear stress on cells. During the assay, detachment of cells was monitored with the Carl Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope using a 10× objective (0.3 NA; EC Plan NEOFLUAR®; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging). Phase-contract images were recorded at 10 sec intervals for a total period of 5 min. The numbers of adherent cells on glass substrates before and after their treatments with this sustained 5-min directional fluid shear were quantified from the recorded microscope images using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The fluidic shear stress (τ0) exerted on cells was calculated using the equation τ0 = (6μQ) / (WH2), where μ is the viscosity of culture media (~10-3 Pa s), Q is the flow rate, and W and H are the microfluidic channel width and height, respectively. Adhesion strength of cells was defined as the fluidic shear stress at which 50% of cells initially attached on glass surfaces would detach after exposed to fluid shear for 5 min. Adhesion strength of PBMCs was examined as a control using the same method but without the low flow rate pre-washing step, as most PBMCs were still floating 12 hrs after cell seeding and were easily washed away with a extreme low shear stress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation (ECCS 1231826; Fu), the UM-SJTU Collaboration on Biomedical Technologies (Fu), the UM Comprehensive Cancer Center Prostate SPORE Pilot Project (NIH/NCI 5 P50 CA069568-15; Fu), the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research (MICHR) (2 UL1 TR000433-06; Fu), and the department of Mechanical Engineering of the University of Michigan (Fu). S. D. Merajver and L. Bao are supported in part by the Avon Foundation, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health. We thank Thomas P. Shanley for providing blood specimens and Nien-Tsu Huang and Katsuo Kurabayashi for help with cell imaging. The Lurie Nanofabrication Facility at the University of Michigan, a member of the National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network (NNIN) funded by the National Science Foundation, is acknowledged for support in microfabrication.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Additional information and graphics as described in the text. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Matera J, Miller MC, Reuben JM, Doyle GV, Allard WJ, Terstappen LWMM, et al. Circulating Tumor Cells, Disease Progression, and Survival in Metastatic Breast Cancer. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:781–791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, Bell DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, Smith MR, Kwak EL, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky A, et al. Isolation of Rare Circulating Tumour Cells in Cancer Patients by Microchip Technology. Nature. 2007;450:1235–1239. doi: 10.1038/nature06385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein CA. Parallel Progression of Primary Tumours and Metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:302–312. doi: 10.1038/nrc2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pantel K, Alix-Panabieres C, Riethdorf S. Cancer Micrometastases. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:339–351. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wicha MS, Hayes DF. Circulating Tumor Cells: Not All Detected Cells Are Bad and Not All Bad Cells Are Detected. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pantel K, Brakenhoff RH, Brandt B. Detection Clinical Relevance and Specific Biological Properties of Disseminating Tumour Cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:329–340. doi: 10.1038/nrc2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu M, Stott S, Toner M, Maheswaran S, Haber DA. Circulating Tumor Cells: Approaches to Isolation and Characterization. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:373–382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.den Toonder J. Circulating Tumor Cells: The Grand Challenge. Lab Chip. 2011;11:375–377. doi: 10.1039/c0lc90100h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vona G, Sabile A, Louha M, Sitruk V, Romana S, Schütze K, Capron F, Franco D, Pazzagli M, Vekemans M, et al. Isolation by Size of Epithelial Tumor Cells: A New Method for the Immunomorphological and Molecular Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:57–63. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64706-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan SJ, Lakshmi RL, Chen P, Lim W-T, Yobas L, Lim CT. Versatile Label Free Biochip for the Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells from Peripheral Blood in Cancer Patients. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;26:1701–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng S, Lin H, Lu B, Williams A, Datar R, Cote R, Tai Y-C. 3d Microfilter Device for Viable Circulating Tumor Cell (Ctc) Enrichment from Blood. Biomed Microdevices. 2011;13:203–213. doi: 10.1007/s10544-010-9485-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talasaz AH, Powell AA, Huber DE, Berbee JG, Roh K-H, Yu W, Xiao W, Davis MM, Pease RF, Mindrinos MN, et al. Isolating Highly Enriched Populations of Circulating Epithelial Cells and Other Rare Cells from Blood Using a Magnetic Sweeper Device. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3970–3975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813188106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stott SL, Hsu C-H, Tsukrov DI, Yu M, Miyamoto DT, Waltman BA, Rothenberg SM, Shah AM, Smas ME, Korir GK, et al. Isolation of Circulating Tumor Cells Using a Microvortex-Generating Herringbone-Chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18392–18397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012539107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, Liu K, Liu J, Yu ZTF, Xu X, Zhao L, Lee T, Lee EK, Reiss J, Lee Y-K, et al. Highly Efficient Capture of Circulating Tumor Cells by Using Nanostructured Silicon Substrates with Integrated Chaotic Micromixers. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2011;50:3084–3088. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S-K, Kim G-S, Wu Y, Kim D-J, Lu Y, Kwak M, Han L, Hyung J-H, Seol J-K, Sander C, et al. Nanowire Substrate-Based Laser Scanning Cytometry for Quantitation of Circulating Tumor Cells. Nano Lett. 2012;12:2697–2704. doi: 10.1021/nl2041707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams AA, Okagbare PI, Feng J, Hupert ML, Patterson D, Göttert J, McCarley RL, Nikitopoulos D, Murphy MC, Soper SA. Highly Efficient Circulating Tumor Cell Isolation from Whole Blood and Label-Free Enumeration Using Polymer-Based Microfluidics with an Integrated Conductivity Sensor. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8633–8641. doi: 10.1021/ja8015022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sekine J, Luo SC, Wang S, Zhu B, Tseng HR, Yu HH. Functionalized Conducting Polymer Nanodots for Enhanced Cell Capturing: The Synergistic Effect of Capture Agents and Nanostructures. Adv Mater. 2011;23:4788–4792. doi: 10.1002/adma.201102151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bichsel CA, Gobaa S, Kobel S, Secondini C, Thalmann GN, Cecchini MG, Lutolf MP. Diagnostic Microchip to Assay 3d Colony-Growth Potential of Captured Circulating Tumor Cells. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2313–2316. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40130d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thiery JP. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions in Tumour Progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A Perspective on Cancer Cell Metastasis. Science. 2011;331:1559–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.1203543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Bolt J, van der Spoel P, Elstrodt F, Schutte M, Martens JWM, Gratama J-W, Sleijfer S, Foekens JA. Anti-Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule Antibodies and the Detection of Circulating Normal-Like Breast Tumor Cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:61–66. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van der Auwera I, Peeters D, Benoy IH, Elst HJ, Van Laere SJ, Prove A, Maes H, Huget P, van Dam P, Vermeulen PB, et al. Circulating Tumour Cell Detection: A Direct Comparison between the Cellsearch System, the Adnatest and Ck-19/Mammaglobin Rt-Pcr in Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;102:276–284. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang L, Lang JC, Balasubramanian P, Jatana KR, Schuller D, Agrawal A, Zborowski M, Chalmers JJ. Optimization of an Enrichment Process for Circulating Tumor Cells from the Blood of Head and Neck Cancer Patients through Depletion of Normal Cells. Biotechnol and Bioeng. 2009;102:521–534. doi: 10.1002/bit.22066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tkaczuk K, Goloubeva O, Tait N, Feldman F, Tan M, Lum Z-P, Lesko S, Van Echo D, Ts’o P. The Significance of Circulating Epithelial Cells in Breast Cancer Patients by a Novel Negative Selection Method. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111:355–364. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9771-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen W, Villa-Diaz LG, Sun Y, Weng S, Kim JK, Lam RH, Han L, Fan R, Krebsbach PH, Fu J. Nanotopography Influences Adhesion, Spreading, and Self-Renewal of Human Embryonic Stem Cells. ACS Nano. 2012;6:4094–4103. doi: 10.1021/nn3004923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metwalli E, Pantano CG. Reactive Ion Etching of Glasses: Composition Dependence. Nucl Instrum Meth B. 2003;207:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon KW, Choi SS, Lee SH, Kim B, Lee SN, Park MC, Kim P, Hwang SY, Suh KY. Label-Free, Microfluidic Separation and Enrichment of Human Breast Cancer Cells by Adhesion Difference. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1461–1468. doi: 10.1039/b710054j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam RHW, Sun YB, Chen WQ, Fu JP. Elastomeric Microposts Integrated into Microfluidics for Flow-Mediated Endothelial Mechanotransduction Analysis. Lab Chip. 2012;12:1865–1873. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21146g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallant ND, Michael KE, Garcia AJ. Cell Adhesion Strengthening: Contributions of Adhesive Area, Integrin Binding, and Focal Adhesion Assembly. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2005;16:4329–4340. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun Y, Chen CS, Fu J. Forcing Stem Cells to Behave: A Biophysical Perspective of the Cellular Microenvironment. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:519–542. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longo DL. Tumor Heterogeneity and Personalized Medicine. New Engl J Med. 2012;366:956–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1200656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marusyk A, Almendro V, Polyak K. Intra-Tumour Heterogeneity: A Looking Glass for Cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:323–334. doi: 10.1038/nrc3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.