Abstract

Background

Congenital heart disease (CHD) has a multifactorial etiology, but a genetic contribution is indicated by heritability studies. To investigate the spectrum of CHD with a genetic etiology, we conducted a forward genetic screen in inbred mice using fetal echocardiography to recover mutants with CHD. Mice are ideally suited for these studies, given they have the same four-chamber cardiac anatomy that is the substrate for CHD.

Methods and Results

Ethylnitrosourea mutagenized mice were ultrasound interrogated by fetal echocardiography using a clinical ultrasound system, and fetuses suspected to have cardiac abnormalities were further interrogated with an ultra-high frequency ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM). Scanning of 46,270 fetuses revealed 1,722 with cardiac anomalies, with 27.9% dying prenatally. Most of the structural heart defects can be diagnosed using the UBM, but not with the clinical ultrasound system. Confirmation with analysis by necropsy and histopathology showed excellent diagnostic capability of UBM for most CHD. Ventricular septal defect was the most common CHD observed, while outflow tract and atrioventricular septal defects were the most prevalent complex CHD. Cardiac/visceral organ situs defects were observed at surprisingly high incidence. The rarest CHD found was hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), a phenotype never seen in mice previously.

Conclusions

We developed a high throughput two-tier ultrasound phenotyping strategy for efficient recovery of even rare CHD phenotypes, including the first mouse models of HLHS. Our findings support a genetic etiology for a wide spectrum of CHD and suggest the disruption of left-right patterning may play an important role in CHD.

Keywords: fetal echocardiography, ultra-high frequency ultrasound biomicroscopy, congenital heart defects, mouse mutagenesis, HLHS

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is one of the most common birth defects, with up to 1% incidence in live births. The heritable nature of CHD is indicated by the increased recurrence risk for CHD, and the observation that syndromic forms of CHD are often associated with chromosomal anomalies, such as 22q11 deletion in DiGeorge syndrome. However, investigations into the genetic basis of CHD has been challenging, given CHD is often sporadic. Even when there is strong evidence of heritability, there may be variable penetrance and variable expressivity. This could reflect the confounding effects of genetic heterogeneity in the human population. In addition, evidence suggests environmental factors can contribute to CHD, indicating a multifactorial etiology to CHD.

Studies in mice have expanded our knowledge of genes that can cause CHD. Mice are well suited for modeling CHD, as they have the same cardiac anatomy as humans, with four chamber hearts and distinct left-right asymmetries that provide separate pulmonary-systemic circulation required for oxygenation of blood. These structures are the major targets of CHD. While knockout mice have yielded new insights into the genetic etiology of CHD, the analysis is limited to one gene at a time. In comparison, forward genetic screens using ethylnitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis can greatly accelerate novel gene discovery. With ENU mutagenesis, every animal by design harbors many mutations. Thus with focused phenotyping, gene discovery can proceed rapidly and without a priori gene bias. By conducting such screens in an inbred mouse strain background, the confounding effects of genetic heterogeneity can be minimized1.

We previously conducted a small-scale mouse forward genetic screen to recover CHD mutants using the Acuson clinical ultrasound system for noninvasive fetal echocardiography2, 3. While echocardiography is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosing CHD, the poor imaging resolution of the Acuson restricted the ultrasound assessments to analysis of hemodynamic function. As a result specific CHD diagnosis could only be made after necropsy and histopathology examination. While CHD mutants were successfully recovered, these limitations compromised the efficacy of the screen and some CHD phenotypes may be missed.

In this study, we incorporated the dual use of the Acuson and the Vevo2100 ultrahigh frequency ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) for cardiovascular phenotyping to recover CHD mutants in a large-scale mouse mutagenesis screen. In contrast to our previous study, the Vevo2100 with its much higher resolution, allowed direct diagnosis of structural heart defects. We could diagnose a wide spectrum of CHD and recovered the first mouse models of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), a rare phenotype never seen in mice previously.

Methods

ENU Mutagenesis and Mouse Breeding

All studies were conducted under an approved Institute Animal Care and Use Committee protocol of the University of Pittsburgh. C57BL/6J males were ENU mutagenized as previously described with G1 males backcrossed to 4–6 G2 daughters and the resulting G3 fetuses were ultrasound scanned in utero2, 3. All offspring from one G1 male were tracked as a distinct pedigree.

Ultrasound Imaging and Doppler Echocardiography

Pregnant G2 dams were sedated with isoflurane, and ultrasound scanned using the Acuson Sequoia C512 with a 15 MHz transducer. Litters with abnormal fetuses were then further scanned using the Vevo2100 UBM with 40MHz transducer for specific CHD diagnosis. The protocol used for ultrasound scanning, including the method for mapping the fetus position in utero is described in Supplemental Methods.

Necropsy, Micro-CT/Micro-MRI Imaging and Histopathology Examinations

Fetuses or neonates were collected and fixed in 10% formalin, then examined by necropsy, micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (micro-MRI) and episcopic fluorescence image capture (EFIC)4, a histopathology examination. EFIC served as the gold standard for CHD diagnosis. All CHD diagnoses were reviewed by a panel of pediatric cardiologists and a pathologist (See Supplemental Methods).

Efficacy of Ultrasound CHD Diagnosis

Efficacy of cardiovascular phenotyping with Acuson vs. Vevo2100 was assessed by Chi-square analysis, with significance set at p < 0.05. The positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of Vevo2100 ultrasound for CHD diagnosis were calculated as described in Supplemental Methods. Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Pregnant dams from our ENU mutagenized C57BL6/J mouse colony were ultrasound scanned using the Acuson ultrasound system equipped with a 15 MHz transducer. The large 2D imaging window (25mm×20mm) provided direct visualization of multiple fetuses, while the small footprint of the transducer facilitated rapid scanning. This allowed quick determination of the total number of embryos in a litter, and their relative orientation in the uterine horn. Together with the spectral Doppler/color flow imaging capability, abnormal fetuses can be readily identified based on the finding of hemodynamic perturbation, hydrops, or growth restriction. The fewer litters with abnormal fetuses identified are further interrogated in a second tier analysis using the higher resolution Vevo2100 (30um axial × 75um lateral resolution vs. Acuson’s 300–500 um resolution)5,6. The Vevo2100 has a much smaller imaging window (15mm×14mm) that allows visualization of only one fetus at a time, but its ultra-high 2D resolution equipped with the same color flow imaging capability as the Acuson5 allows direct diagnosis of structural heart defects.

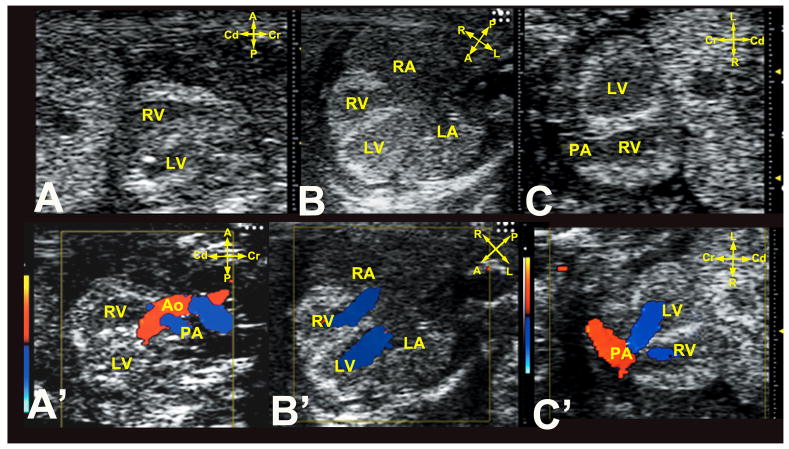

Vevo2100 scanning was conducted using 40MHz transducer with three diagnostic imaging planes, including sagittal (Figure 1A,A′), transverse four-chamber (Figure 1B,B′) and frontal imaging planes (Figure 1C,C′). To determine heart and stomach situs, scans were conducted using two of three orthogonal imaging planes defined by the embryo’s body axes2. Abnormal fetuses were rescanned on multiple days and if deemed inviable to term, they were harvested preterm. Subsequently, necropsy, micro-CT/micro-MRI and/or histopathology examinations were used to confirm the CHD diagnosis. Typically scans with the Acuson had ultrasound exam time of 55±16(SD) sec/fetus for normal fetuses (median: 52sec; range 34sec ~100 sec; based on 68 litters with 434 normal fetuses), and 64±15(SD) sec/fetus for abnormal fetuses (median: 61sec; range: 32sec~105 sec; based on 57 litters with 107 abnormal fetuses). The second tier interrogation of the abnormal fetuses using the Vevo2100 had much longer exam time of 1049±297(SD) sec/fetus (median: 1035sec; range: 600sec~1500sec; based on 27 abnormal fetuses in 20 litters). Overall, 20 litters can be ultrasound scanned per day, with 15 minutes or less required for a litter of 6–8 fetuses, with longer scan times for litters with abnormal fetuses.

Figure 1. Ultrasound imaging planes for cardiovascular phenotying.

Cardiac diagnosis with the UBM is carried out using sagittal (A,A′), transverse four-chamber (B,B′), and frontal (C,C′) imaging planes. Note the anterior-posterior (A–P) axis is equivalent to the body’s dorsal-ventral axis.

A, anterior; P, posterior; L, left; R, right; Cr, cranial; Cd, caudal.

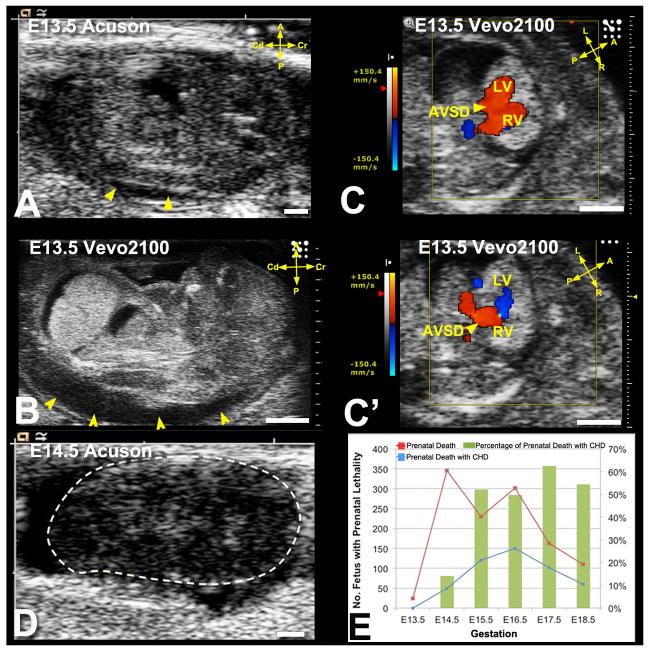

Fetuses were scanned from E13.5–E18.5, with a mean of E15.2±1.4(SD) and median of E15.5. As ventricular chamber and outflow tract (OFT) septation are not completed until E13.5–14.5, scanning at E13.5–15.5 should minimize false positive CHD diagnosis that might reflect developmental delay. Also problematic with earlier scans is echogenicity of blood in younger embryos (due to nucleated erythrocytes), making it difficult to visualize the endocardial lumen, detracting from the otherwise high UBM 2D spatial resolution. Given these considerations, our fetal ultrasound screening was predominantly conducted at E14.5–E15.5, with earlier scans conducted if dead embryos were observed at E14.5–E15.5 (Figure 2A–D).

Figure 2. Ultrasound detection of prenatal lethality.

(A–D) Acuson (A) and Vevo2100 (B) imaging of an E13.5 fetus showed hydrops (A,B, arrowheads). Vevo2100 also showed AVSD (arrowhead in C) with common valve regurgitation (C′ arrowhead). This fetus was found dead the next day (D).

(E). Prenatal death with and without CHD detected by ultrasound screening.

Scale bar=1mm.

Prevalence of Developmental Anomalies Identified by Ultrasound Phenotyping

Using the two-tier ultrasound phenotyping strategy, we screened 46,270 G3 fetuses from 1,381 G1 pedigrees (August, 2010–March, 2012). We identified 2,590 abnormal fetuses exhibiting a spectrum of cardiac and noncardiac defects (Supplemental Table S1 and Figure S1). Cardiac anomalies were found in 1,722 fetuses (3.7%), which accounted for 66.5% of all developmental anomalies detected. In contrast, the incidences of extracardiac defects were much lower ranging from 2–8% (Supplemental Table S1). These included craniofacial defects, limb anomalies, body wall closure defects, and laterality defects including heterotaxy with discordant left-right heart and stomach positioning and also situs inversus totalis (dextrocardia/dextrogastria) (Supplemental Table S1).

Association of Prenatal Lethality and Growth Restriction with Cardiac Defects

The majority of fetuses with severe cardiovascular defects were observed to expire between E15.5 to term, while less than 20% of deaths at E14.5 were associated with CHD (Figure 2E). Cardiac anomalies were overall enriched in mutants with noncardiac defects (Supplemental Table S1). Thus cardiac defects were found in 80.3% of mutants with body wall closure defects and 92.3% of mutants with heterotaxy. Growth retardation was also highly associated with cardiac defects, with 88.7% of growth-restricted fetuses exhibiting cardiac defects. More than 25% of fetuses (481/1722; 27.9%) with cardiac defects died prenatally, showing the importance of screening prenatally. This included 15.1% (260/1722) fetuses found dead with follow-up ultrasound scans and 12.8% (221/1722) fetuses harvested prenatally given pending death was indicated with ultrasound presentations such as hydrops, pericardial effusion, dilated heart with bradycardia/arrhythmia, and/or severe inflow or outflow regurgitation (Figure 2A–D; also see Supplemental Movie 1A–D).

Recovery of a Wide Spectrum of Structural Heart Defects

A wide spectrum of CHD was recovered from the ultrasound screen (Table 1). This included OFT defects, left or right heart obstructive lesions, cardiac septation defects, coronary fistulas (Figure 3, Supplemental Movie 2A–D) and cardiac situs anomalies. In 90 pedigrees, two or more G3 fetuses were observed to have the same structural heart defect phenotype. Such pedigree with multiple affected fetuses were curated in the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) database as part of the Bench to Bassinet collection of mutant mouse lines (http://www.informatics.jax.org/searchtool/Search.do?query=b2b&submit=Quick+Search) and the sperm from the G1 males were cryopreserved at the Jackson Laboratory (Supplemental Table S2). The most common structural heart defect observed was ventricular septal defect (VSD) (50%), while amongst complex CHD phenotypes, OFT defects were the most common (36.1%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Efficiency of Cardiovascular Phenotyping with Acuson vs. Vevo2100

| Ultrasound Diagnosis | Acuson* | Vevo2100* | p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal Echocardiography Findings n=(1,457)‡ | |||

| Cardiac Structural Defects (n=352; 24%) | |||

| Septal Defects | 17 (4.8%) | 241 (68.5%) | <0.01 |

| VSD | 15 (4.3%) | 176 (50%) | <0.01 |

| AVSD | 2 (0.6%) | 65 (18.5%) | <0.01 |

| Outflow Tract Defects | 12 (3.4%) | 127 (36.1%) | <0.01 |

| DORV/Overriding Aorta | 9 (2.6%) | 75 (21.3%) | <0.01 |

| -With VSD | 9 (2.6%) | 57 (16.2%) | <0.01 |

| -With AVSD | 0 (0%) | 18 (5.1%) | <0.01 |

| -With pulmonary stenosis | 0 (0%) | 17 (4.8%) | <0.01 |

| PTA/PA | 3 (0.9%) | 38 (10.8%) | <0.01 |

| -With VSD | 3 (0.9%) | 25 (7.1%) | <0.01 |

| -With AVSD | 0 (0%) | 13 (3.7%) | <0.01 |

| TGA | 0 (0%) | 14 (4.0%) | <0.01 |

| -With VSD | 0 (0%) | 13 (3.7%) | <0.01 |

| -With AVSD | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1.000 |

| -With pulmonary stenosis | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1.000 |

| Left Heart Obstruction Lesions | 7 (2.0%) | 23 (6.5%) | <0.01 |

| Mitral Atresia/Stenosis | 0 (0%) | 8 (2.3%) | <0.05 |

| Aortic Atresia/Stenosis/Coarctation | 7 (2.0%) | 15 (4.3%) | 0.083 |

| Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.1%) | 0.133 |

| Right Heart Obstruction Lesions | 10 (2.8%) | 50 (12.2%) | <0.01 |

| Tricuspid Atresia/Hypoplasia | 0 (0%) | 15 (4.3%) | <0.01 |

| Pulmonary Stenosis | 10 (2.8%) | 35 (9.9%) | <0.01 |

| Hypoplastic Right Heart Syndrome | 0 (0%) | 11 (3.1%) | <0.01 |

| Coronary Artery Fistula | 4 (1.1%) | 8 (2.3%) | 0.244 |

| Cardiac Situs Anomalies | 0 (0%) | 40 (11.4%) | <0.01 |

| Dextrocardia | 0 (0%) | 34 (9.7%) | <0.01 |

| Mesocardia | 0 (0%) | 6 (1.7%) | <0.05 |

| Non-Specific Abnormal Findings (n=1105) | |||

| Total Arrhythmia | 262 | 262 | 1.000 |

| Without Structural Defects | 103 | 103 | 1.000 |

| Total Hydrops/Pericardial Effusion | 598 | 635 | 0.113 |

| Without Structural Defects | 344 | 364 | 0.362 |

| Total Hemodynamic Perturbations§ | 1,010 | 1,030 | 0.110 |

| Mild Without Structural Defects | 670 | 690 | 0.382 |

Values in parentheses represent percentage of affected fetuses amongst 352 fetuses identified as having CHD based on two-tier ultrasound scanning.

p values from Chi-square analysis.

1,457 fetuses identified with cardiac defects by two-tier ultrasound screening.

Hemodynamic pertubations including IFT and OFT increased velocity and regurgitation.

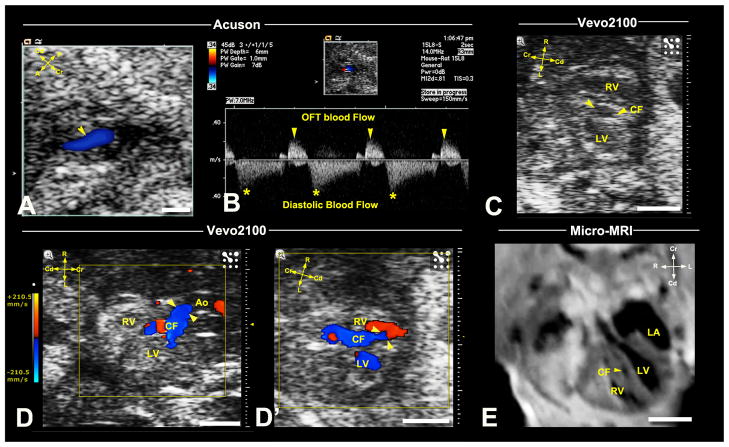

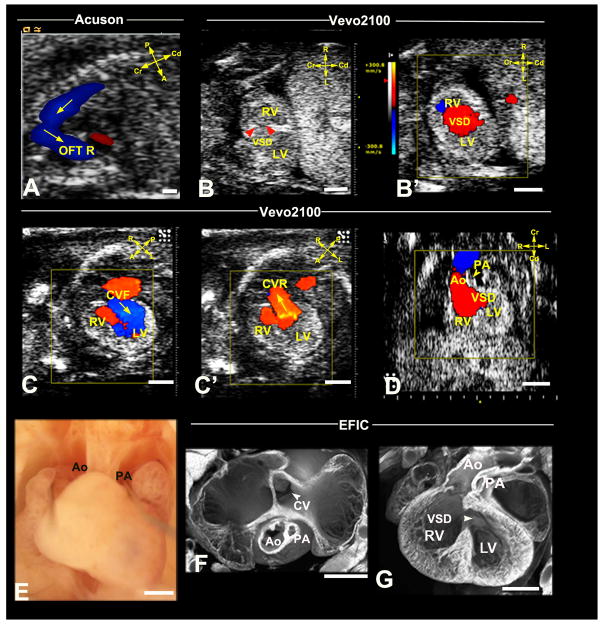

Figure 3. Ultrasound detection of coronary fistula.

Acuson imaging detected an E16.5 fetus with abnormal blood flow (arrowhead) associated with the OFT (A), which spectral Doppler showed occurred at diastole (B). Vevo2100 (C,D,D′) imaging in the frontal view revealed a vessel in the ventricular septum (C), which color flow confirmed is a coronary fistula (CF) originating from the aortic root (arrowheads in D), connecting to the RV (arrowheads, D′). This vessel was also visualized by micro-MRI (E,arrowhead). Scale bar=1mm.

Outflow Tract Anomalies

The most common OFT anomaly was double outlet right ventricle (DORV)/overriding aorta (21.3%). Shown in Figure 4 is a fetus exhibiting DORV with anterior placement of the aorta and subpulmonary VSD, a phenotype clinically referred to as Taussig-Bing sub-type of DORV. This mutant also exhibited heterotaxy with abnormal right-sided, rather than left-sided stomach (Supplemental Movie3A–E). Also observed was persistent truncus arteriosus (PTA) (Figure 5A–E) and transposition of the great arteries (TGA) (Table 1). Given the very small size of the fetal mouse heart, even with the higher resolution of the Vevo2100, DORV was not reliably distinguished from overriding aorta, nor is PTA always distinguishable from pulmonary atresia. Therefore, we grouped DORV with overriding Ao, and PTA with pulmonary atresia (Table 1).

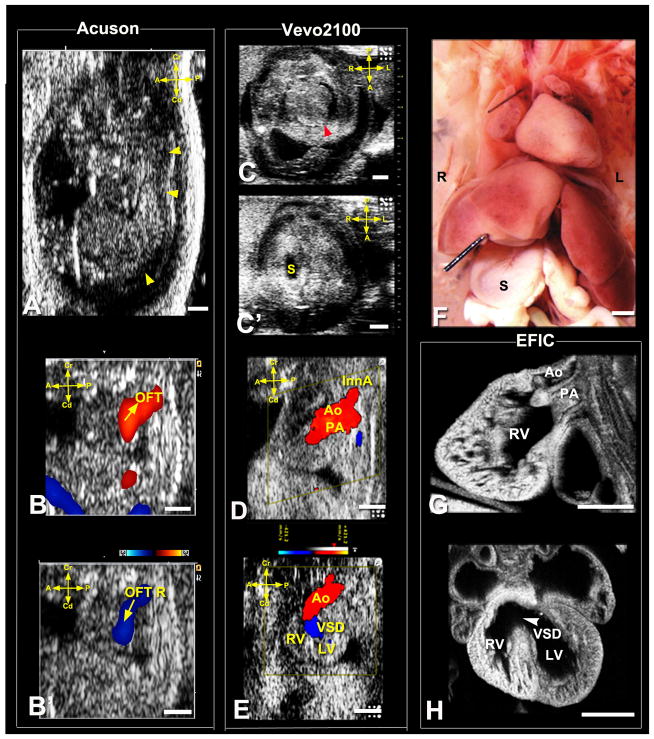

Figure 4. Ultrasound diagnosis of heterotaxy with Taussig-Bing DORV.

Acuson imaging (A,B,B′) showed an E15.5 fetus with hydrops (arrowheads) and OFT regurgitation (OFT R). Vevo2100 imaging (C,C′) showed heterotaxy with heart apex on left (C,arrowhead) and stomach to right (S,C′), which was confirmed by necropsy (F). Vevo2100 (D,E) and EFIC (G,H) imaging showed aorta (Ao) anterior and PA posterior with both outflows connected to RV (D,G,E), with large VSD (E,H).

L, left; R, right; InnA, innominate artery; Scale bar=1mm.

Figure 5. Ultrasound diagnosis of persistent truncus arteriosus.

Acuson spectral Doppler showed an E17.5 fetus OFT regurgitation (A,arrowhead; OFT asterisks, forward flow). Vevo2100 revealed a single OFT overriding the ventricular septum with a VSD (arrowhead B). This was associated with OFT regurgitation, indicated by red forward and blue reverse blood flow (B,B′), further confirmed with necropsy (C) and EFIC histology (D,E). A single OFT (CT in C,D) was observed overriding the septum with ventricular noncompaction, a perimembranous (D,arrowhead) and muscular VSDs (arrowheads in D,E).

Scale bar=1mm.

Atrioventricular Septal Defects and Right/Left Heart Obstructive Lesions

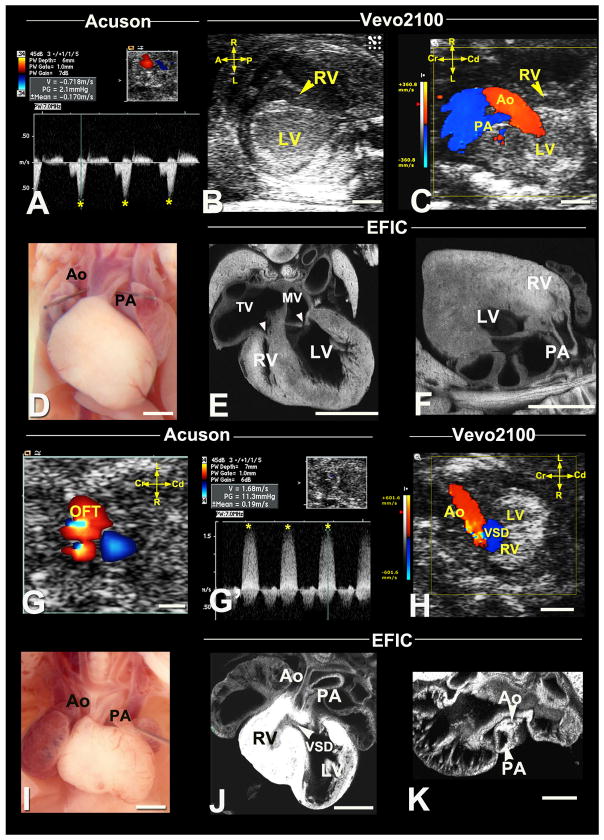

Atrioventricular septal defects (AVSD) were also commonly observed in our screen, especially in conjunction with OFT anomalies (Figure 6; Supplemental Movie4A–E) (Table 1). Secundum atrial septal defect and foramen ovale were not distinguishable and were not tracked. Amongst right heart obstructive lesions, pulmonary stenosis was the most common. We observed some cases of hypoplastic right heart syndrome and also hypoplastic tricuspid (Figure 7A–F). Amongst left heart obstructive lesions, the most common was aortic stenosis/coarctation (Figure 7G–K). Most unexpected was the finding of fetuses with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) (Figure 8).

Figure 6. Diagnosis of DORV with hypoplastic PA and AVSD.

Acuson imaging detected an E16.5 fetus OFT regurgitation (OFT R in A). Vevo2100 imaging (B,B′) revealed a RV-LV shunt, indicating a VSD (arrowheads B). Vevo2100 imaging in the transverse view (C,C′) showed IFT forward (C,arrow) and regurgitant (C′,arrow) flow, while the sagittal view (D) showed majority of the aorta connects to the RV with an adjacent small vessel (arrowhead, PA) and a VSD. Necropsy (E) and EFIC histology (F,G) revealed a hypoplastic PA (E–G) and large VSD (arrowhead,G). A common atrioventricular valve (CV in F) was observed in the transverse view (F).

CVF, CVR: common atrioventricular valve forward flow, reverse flow. Scale bar=1mm.

Figure 7. Diagnosis of right and left heart obstructive lesions.

(A–F) Hypoplastic right heart syndrome.

Acuson Doppler imaging detected an E17.5 fetus with increased velocity in the IFT (A, asterisks). Vevo2100 revealed a hypoplastic RV (B,C) with hypoplastic PA. Necropsy (D) of the stillborn pup confirmed hypoplastic PA, with EFIC imaging (E,F) also showing a hypoplastic RV, hypoplastic tricuspid valve (TV) compared to the mitral valve (MV) (arrowheads,E) and hypoplastic PA connected to RV (arrowhead,F).

(G–K) Hypoplastic ascending aorta with VSD.

Acuson color flow revealed an E17.5 fetus with OFT aliasing (G), which spectral Doppler (G′) showed high velocity (G′,asterisks). Vevo2100 color flow (H) revealed aortic stenosis with VSD, consistent with the spectral Doppler (G′) findings. Necropsy (I) and EFIC (J,K) histology showed hypoplastic ascending aorta. Also note the VSD (J) and small RV with hypertrophy (J). Scale bar=1mm.

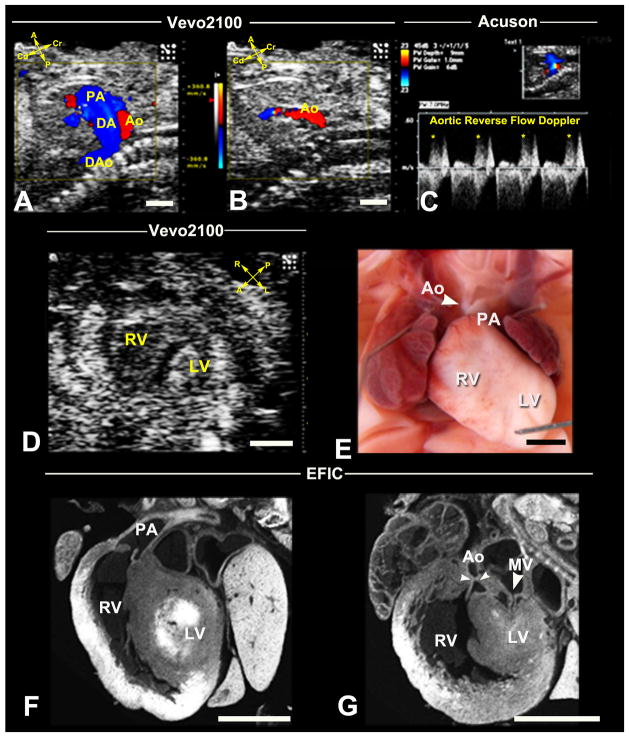

Figure 8. Recovery of HLHS mutant by ultrasound phenotyping.

Vevo2100 in sagittal view (A) showed an E16.5 fetus with reversed aortic blood flow. This is seen in diastole (B), and was confirmed by spectral Doppler (C). Vevo2100 imaging in the short axis view (D) showed hypoplastic LV. Necropsy of the stillborn pup (E) revealed hypoplastic aorta and small LV, confirmed by EFIC histology (F,G) to be HLHS with small mitral valve orifice, small LV and hypoplastic aorta.

DA, ductus artery; DAo, descending aorta. Scale bar=1mm.

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome

HLHS is one of the rarest phenotypes recovered in our screen - 4 HLHS fetuses were identified from over 46,000 fetuses scanned. This was derived from three independent G1 pedigrees. HLHS is characterized by underdevelopment of the left side of the heart, including hypoplasia of the left ventricle (LV), the mitral valve, the aorta and aortic arch (Figure 8). This phenotype has never been observed in mice previously. In mutant line 635, ultrasound diagnosed one fetus with HLHS at E14.5, which was confirmed with follow up ultrasound analysis on subsequent days. Color flow imaging showed reverse aortic flow from the descending to ascending aorta (Figure 8A–C). Mitral valve atresia was indicated by lack of color inflow, while 2D imaging showed a very small LV with little or no lumen (Figure 8D). This mutant was stillborn and necropsy revealed hypoplastic ascending aorta (Figure 8E), with subsequent EFIC histopathology showing small LV with almost no lumen, hypoplastic ascending aorta and hypoplastic mitral valve. These findings together confirmed the ultrasound diagnosis of HLHS (Figure 8F,G) (Supplemental Movie5A–C). Heritability of the HLHS phenotype was demonstrated in this mutant line with the recovery of two HLHS mutants from 62 offspring screened. In the other two mutant lines, only a single HLHS fetus was found amongst 18 and 29 offspring interrogated, respectively. Given the rarity of HLHS, all three HLHS mutant lines were curated in MGI and sperm was cryopreserved at the Jackson Laboratory.

Congenital Heart Defects Associated with Laterality Defects

As visceral organ situs can be determined by ultrasound phenotyping with the Vevo2100, we assessed situs anomalies as a part of the routine CHD phenotyping workflow. Surprisingly, over half (49/90) of the mutant lines with CHD exhibited laterality defects (Supplemental Table S2). This included fetuses with situs inversus totalis with mirror symmetric visceral organ situs, and heterotaxy with randomized visceral organ situs. Nearly all heterotaxy mutants had complex CHD, which was readily detected by echocardiography (see example in Figure 4). In contrast, mutants exhibiting situs inversus totalis generally did not have CHD, although some had VSDs.

Efficacy of Congenital Heart Defect Diagnosis with the UBM vs. Acuson

We compared the efficacy of the Acuson vs. the UBM in CHD diagnosis, by examining the ultrasound findings obtained in 1,457 abnormal fetuses that were scanned using both ultrasound systems (Table 1). UBM was significantly better in detecting structural heart anomalies, such as septal defects (p<0.01), OFT defects (p<0.01), left heart obstructive lesions (p<0.01), right heart obstructive lesions (p<0.01), and cardiac situs anomaly (p<0.01). We noted some structural heart defects were only detected with the UBM, including HLHS, HRHS, mitral valve atresia/stenosis, tricuspid atresia/stenosis, mesocardia/dextrocardia, and TGA (Table 1). However, there was no difference in the efficiency for detection of hemodynamic perturbations, such as regurgitant flow or velocity increase in the inflow tract (IFT) or OFT, and other non-specific cardiac indications encompassing arrhythmia, hydrops/pericardial effusion (Table 1).

Accuracy of Congenital Heart Defect Diagnoses by Vevo2100 Ultrasound

The efficacy of Vevo2100 ultrasound phenotyping of CHD was evaluated using EFIC histopathology as the gold standard for structural heart defect diagnosis (Table 2). In total, 524 fetuses interrogated by two-tier ultrasound screening were evaluated by EFIC imaging (Supplemental Figure S2). This included 277 fetuses identified with cardiac lesions, 161 fetuses identified as without CHD from amongst these same litters with the affected fetuses, and 86 fetuses initially Acuson identified with abnormal findings, but subsequently Vevo2100 scanned and diagnosed as without CHD. This combined analysis of 277 fetuses with cardiac lesions and 247 fetuses without cardiac defects showed negative predictive value (NPV) ranging from 80.9%–100% (Table 2, Supplemental Table S3). In contrast, positive predictive value (PPV) varied from 60%–100%, with the lowest associated with aortic anomalies, tricuspid anomalies and coronary fistulas (Table 2, Supplemental Table S3), indicating the latter defects were missed more frequently.

Table 2.

Accuracy of Vevo2100 Ultrasound Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease*

| CHD diagnosis | True positive diagnosis | True negative diagnosis | False positive diagnosis | False negative diagnosis | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Septal Defects† | 156 | 292 | 7 | 69 | 95.7% | 80.9% |

| Outflow Tract Defects‡ | 105 | 376 | 18 | 25 | 85.4% | 93.8% |

| HLHS§ | 4 | 520 | 0 | 0 | 100% | 100% |

| HRHS|| | 7 | 513 | 2 | 2 | 77.8% | 99.6% |

| MS/MA# | 6 | 514 | 2 | 2 | 75% | 99.6% |

| AS/AA/COA** | 9 | 489 | 6 | 20 | 60% | 96.1% |

| Tricuspid Hypoplasia/Atresia | 6 | 510 | 4 | 4 | 60% | 99.2% |

| Pulmonary Stenosis | 9 | 499 | 1 | 15 | 90% | 97.1% |

| Coronary Artery Fistula | 5 | 508 | 2 | 9 | 71.4% | 98.3% |

| Cardiac Situs Defects | 18 | 501 | 0 | 5 | 100% | 99% |

| Total Diagnoses | 325 | 4722 | 42 | 151 |

Total number of fetuses/pups analyzed =524, including 277 identified by Vevo ultrasound as with CHD+161 littermates of the affected fetuses but Vevo ultrasound identified as without CHD + 86 fetuses from litters Vevo ultrasound identified as without CHD (see Figure S2).

VSD, AVSD.

TGA, DORV and PTA/PA,

HLHS= hypoplastic left heart syndrome,

HRHS=hypoplastic right heart syndrome.

MS/MA= mitral valve stenosis/mitral valve atresia,

AS/AA/COA= aortic stenosis/aortic atresia/coarctation.

Overall, our analysis showed excellent diagnostic capability of Vevo2100 ultrasound for most CHD. For septal defects, PPV (95.7%) was high, but NPV (80.9%) was lower. This mainly reflects the failure to detect very small VSDs. For OFT defects, even though NPV (93.8%) was high, we observed PPV of only 85.4%. Thus amongst 130 OFT defects diagnosed by EFIC, 25 were missed by the Vevo2100 ultrasound scans; these largely comprised of TGAs and DORVs. We found HLHS as the only CHD diagnosis with 100% accuracy (Table 2, Supplemental Table S3). For cardiac situs, PPV of 100% was observed with 99% NPV, a reflection of high accuracy of Vevo2100 ultrasound in determining cardiac situs. In 5 of 23 cases of dextrocardia missed by Vevo2100 ultrasound, all were associated with situs inversus totalis.

Discussion

Our study showed the efficacy of noninvasive mouse fetal ultrasound imaging with the Acuson and Vevo2100 ultrasound systems for cardiovascular phenotyping. The Acuson allowed high throughput screening for quick identification of abnormal fetuses, with subsequent UBM interrogation for specific CHD diagnosis. Scan time of approximately 18 min/abnormal fetus was required for the UBM, but only 1 min/fetus with the Acuson. Previous studies by Phoon et al using another UBM instrument reported scan time of approximately 1 hr per litter6, consistent with our observation. The ultrasound system used in the previous studies could not diagnose specific structural heart defects given the lack of color flow Doppler function, but nevertheless, their hemodynamic assessments showed the outflow cushions perform valve-like function critical for survival of the early mouse embryo7.

Using Vevo2100 equipped with color flow Doppler, while we observed NPV for most CHDs was >93%, PPV varied with low diagnostic capability for valvular defects, coronary artery fistulas and small VSDs. These findings are similar to those reported in human fetal ultrasound studies8. Comparison of CHD diagnosis achieved with Vevo2100 vs. post-mortem micro-CT imaging showed similar high diagnostic accuracy for most CHDs, except for aortic arch anomalies and situs defects9. Current UBM technology cannot visualize the small aortic arch vessels, but these can be detected by contrast enhanced micro-CT9. Micro-CT also gave high accuracy in detection of situs anomalies, as the animal’s left-right axis can be predictably fixed during CT-scanning9. In contrast, the fetus orientation in utero during ultrasound scanning is highly variable.

Recovery of CHD Mutants by Fetal Ultrasound Phenotyping

Our screen encompassing over 46,000 fetuses is one of the largest CHD screen to date. We observed a 3.7% incidence of cardiac defects and curated and cryopreserved over 90 mutant mouse lines with CHD. We observed CHD is highly associated with growth retardation, and extracardiac anomalies. This is consistent with clinical studies showing intrauterine growth restriction being a significant risk factor for CHD10, and the report that CHD is linked with chromosomal abnormalities, suboptimal growth, and extracardiac malformations10. We found >25% of fetuses with cardiac defects died prenatally, with many expiring between E15.5 and E16.5, equivalent to 8–12 week gestation human embryos11. Interestingly, clinical studies have shown higher fetal death associated with CHD in human fetuses <15 weeks and an overall increase in CHD incidence in fetuses dying before term8, 12, 13.

With fetal ultrasound imaging, we recovered at-risk fetuses which otherwise would be missed in a postnatal screen. Moreover, with identification of fetuses with CHD by ultrasound, we could exercise more caution in recovering stillborn pups, which otherwise might be cannibalized by the mother. We note another study screened for CHD mutants in a mouse mutagenesis screen with postnatal collection of stillborn pups and conducting phenotyping by histopathology14. While CHD mutants can be recovered in this manner, it is not high throughput and a significant fraction of the CHD mutants would be missed. Our analysis of stillborn pups showed only 13% had CHD, most of which were isolated VSDs (unpublished observations).

Wide Spectrum of CHD Recovered from the Mutagenesis Screen

The most prevalent cardiac defect found was VSD, observed in 50% of the CHD mutants, half of which were isolated VSDs. VSD is also the most common CHD observed clinically, suggesting a large number of genes may contribute to VSD15. OFT anomalies (36%) and AVSD (19%) were the most common complex CHD. Amongst OFT defects, DORV was the most common, accounting for more than 50% of the OFT anomalies observed. DORV is also one of the most common OFT anomalies seen in patients with CHD. Surprisingly, we did not observe Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), but TOF has been observed in knockout mouse models, albeit with variable penetrance16.

Another unexpected finding was the large number of CHD mutants with laterality defects, with dextrocardia/mesocardia seen in 11% of CHD mutants. In comparison, human clinical studies17 showed laterality defects accounts for only 3% of all CHD. As our study showed heterotaxy mutants often died prenatally from complex CHDs, human conceptuses with complex CHD associated with heterotaxy may be underrepresented in the clinical population. Indeed, studies have shown an excess of complex lesions in human fetuses with CHD that did not survive to term15. Together, these findings suggest genes regulating left-right patterning may play an important role in complex CHD.

Mouse Models of HLHS

HLHS was the rarest CHD phenotype recovered, with an incidence of 1.1% amongst CHD mutants in our screen. HLHS is also clinically rare, the prevalence varying depending on the patient population8,15. The recovery of HLHS mutants was made possible both by the scale of our screen and the efficacy of the UBM in yielding hemodynamic and structural information. Although HAND-1 null mutant mice have hypoplastic LV18, they do not exhibit all three essential features of HLHS. It should be noted our screen was designed to recover recessive mutations, but only 4 HLHS fetuses were recovered from over 100 fetuses ultrasound scanned in three independent pedigrees, which is inconsistent with a monogenic recessive etiology. We note clinical studies have shown HLHS is genetically heterogeneous and possibly with a multigenic etiology19.

Genetic Contribution to Congenital Heart Disease

Findings from our forward genetic screen support a genetic etiology for a wide spectrum of CHD, including VSD, the most common cardiac defects and HLHS, one of the most severe CHDs. While our screen was conducted using a two-generation backcross breeding scheme designed to recover recessive mutations, every G1 pedigree is estimated to have more than 20 deleterious mutations20. This provides a genomic context for modeling some of the complex genetics of CHD seen in the human population, including CHD with a multigenic etiology. Perhaps this accounts for our success in recovering HLHS mutants.

One CHD phenotype thus far not observed in our screen is Ebstein’s anomaly, a CHD involving malformation of the tricuspid valve. It is one of the rarest CHD estimated at a prevalence of 1 in 200,000. As this CHD phenotype should be readily detectable by UBM, failure to find Ebstein’s anomaly could simply reflect insufficient sample size. Alternatively strain background effects may be a contributing factor. Various clinical and animal model studies have indicated a genetic etiology for Ebstein’s anomaly21, but this CHD also has been linked to environmental exposures22, suggesting possible involvement of genetic and environmental factors.

Limitation

While fetal ultrasound scans can be initiated in early gestation (<E15.5), care must be exercised to ensure the anomalies detected do not represent developmental delay. Yet another limitation is the potential failure to recover isolated small VSDs and vascular anomalies such as coronary fistula and valvular defects. While such defects could be readily diagnosed by the UBM, they may be missed by the initial Acuson scans in a two-tier screen.

Conclusion

We showed noninvasive fetal echocardiography can serve as a sensitive and high throughput imaging modality for CHD diagnosis. Our forward genetic screen using fetal ultrasound imaging has provided evidence of a genetic etiology for a wide spectrum of CHD, including HLHS. While our breeding scheme was optimized for detection of recessive mutations, our findings suggest a more complex multigenic etiology for HLHS and perhaps other CHD. We propose ENU mutagenesis using inbred mice can provide an ideal genomic context to interrogate and model the complex genetics of human CHD.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Summary.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is one of the most common birth defects. Investigations into the genetic etiology of CHD has been challenging, given the sporadic nature, and variable penetrance and expressivity of CHD. Further complications come from indications that environmental factors also may contribute to CHD. To interrogate the genetic etiology of CHD, we undertook a forward genetic screen in chemically mutagenized C57BL6 inbred mice to recover CHD mutants. A two-tier ultrasound screening protocol was developed involving initial scans using the Acuson clinical ultrasound system to identify fetuses with cardiac defects, followed by detailed scans of the abnormal fetuses for CHD diagnosis using the ultrahigh frequency Vevo2100 ultrasound biomicroscopy. We scanned 46,270 fetuses and identified 1,722 with cardiac defects, over 25% of which died prenatally. A wide spectrum of CHD was observed, most of which could be diagnosed using the Vevo2100, but not with the Acuson. Confirmation of the CHD diagnosis with necropsy and histopathology showed excellent diagnostic capability of UBM for most CHD. Ventricular septal defect was the most common CHD observed, while outflow tract and atrioventricular septal defects were the most prevalent complex CHD. Laterality defects including heterotaxy were observed at surprisingly high incidence. The rarest CHD found was hypoplastic left heart syndrome, a phenotype never seen in mice previously. Our findings support a genetic etiology for a wide spectrum of CHD and suggest mouse fetal echocardiography together with forward genetic screens can be used to interrogate and model the complex genetics of human CHD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Chien-Fu Chang, Cheng Cui and Maliha Zahid for data analyses and Dr You Li for helpful discussions and manuscript review. We also thank Dr. Wei Chen for consultation on the statistical analysis.

Sources of Funding

Funded by NIH UO1HL098180.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Justice MJ. Capitalizing on large-scale mouse mutagenesis screens. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:109–115. doi: 10.1038/35038549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen Y, Leatherbury L, Rosenthal J, Yu Q, Pappas MA, Wessels A, Lucas J, Siegfried B, Chatterjee B, Svenson K, Lo CW. Cardiovascular phenotyping of fetal mice by noninvasive high-frequency ultrasound facilitates recovery of ENU-induced mutations causing congenital cardiac and extracardiac defects. Physiol Genomics. 2005;24:23–36. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00129.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu Q, Shen Y, Chatterjee B, Siegfried BH, Leatherbury L, Rosenthal J, Lucas JF, Wessels A, Spurney CF, Wu YJ, Kirby ML, Svenson K, Lo CW. ENU induced mutations causing congenital cardiovascular anomalies. Development. 2004;131:6211–6223. doi: 10.1242/dev.01543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenthal J, Mangal V, Walker D, Bennett M, Mohun TJ, Lo CW. Rapid high resolution three dimensional reconstruction of embryos with episcopic fluorescence image capture. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2004;72:213–223. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tobita K, Liu X, Lo CW. Imaging modalities to assess structural birth defects in mutant mouse models. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2010;90:176–184. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji RP, Phoon CK. Noninvasive localization of nuclear factor of activated T cells c1−/− mouse embryos by ultrasound biomicroscopy-Doppler allows genotype-phenotype correlation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nomura-Kitabayashi A, Phoon CK, Kishigami S, Rosenthal J, Yamauchi Y, Abe K, Yamamura K, Samtani R, Lo CW, Mishina Y. Outflow tract cushions perform a critical valve-like function in the early embryonic heart requiring BMPRIA-mediated signaling in cardiac neural crest. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1617–1628. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00304.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marek J, Tomek V, Skovranek J, Povysilova V, Samanek M. Prenatal ultrasound screening of congenital heart disease in an unselected national population: A 21-year experience. Heart. 2011;97:124–130. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.206623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim AJ, Francis R, Liu X, Devine WA, Ramirez R, Anderton SJ, Wong LY, Faruque F, Gabriel GC, Chung W, Leatherbury L, Tobita K, Lo CW. Microcomputed tomography provides high accuracy congenital heart disease diagnosis in neonatal and fetal mice. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:551–559. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez-Delboy A, Simpson LL. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of congenital heart disease and intrauterine growth restriction: A case-control study. J Clin Ultrasound. 2007;35:376–381. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otis EM, Brent R. Equivalent ages in mouse and human embryos. Anat Rec. 1954;120:33–63. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerlis LM. Cardiac malformations in spontaneous abortions. Int J Cardiol. 1985;7:29–46. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(85)90170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman JI. Incidence of congenital heart disease: II. Prenatal incidence. Pediatr Cardiol. 1995;16:155–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00794186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamp A, Peterson MA, Svenson KL, Bjork BC, Hentges KE, Rajapaksha TW, Moran J, Justice MJ, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Moskowitz IP, Beier DR. Genome-wide identification of mouse congenital heart disease loci. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3105–3113. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1890–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makki N, Capecchi MR. Cardiovascular defects in a mouse model of HOXA1 syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:26–31. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu L, Belmont JW, Ware SM. Genetics of human heterotaxias. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:17–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFadden DG, Barbosa AC, Richardson JA, Schneider MD, Srivastava D, Olson EN. The Hand1 and Hand2 transcription factors regulate expansion of the embryonic cardiac ventricles in a gene dosage-dependent manner. Development. 2005;132:189–201. doi: 10.1242/dev.01562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinton RB, Martin LJ, Rame-Gowda S, Tabangin ME, Cripe LH, Benson DW. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome links to chromosomes 10q and 6q and is genetically related to bicuspid aortic valve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1065–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balling R. ENU mutagenesis: Analyzing gene function in mice. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2001;2:463–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.2.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Digilio MC, Bernardini L, Lepri F, Giuffrida MG, Guida V, Baban A, Versacci P, Capolino R, Torres B, De Luca A, Novelli A, Marino B, Dallapiccola B. Ebstein anomaly: Genetic heterogeneity and association with microdeletions 1p36 and 8p23.1. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:2196–2202. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lupo PJ, Langlois PH, Mitchell LE. Epidemiology of Ebstein anomaly: Prevalence and patterns in Texas, 1999–2005. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1007–1014. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.