Abstract

Rationale

Social play behavior is a characteristic form of social behavior displayed by juvenile and adolescent mammals. This social play behavior is highly rewarding, and of major importance for social and cognitive development. Social play is known to be modulated by neurotransmitter systems involved in reward and motivation. Interestingly, psychostimulant drugs, such as amphetamine and cocaine, profoundly suppress social play, but the neural mechanisms underlying these effects remain to be elucidated.

Objective

In this study we investigated the pharmacological underpinnings of amphetamine- and cocaine-induced suppression of social play behavior in rats.

Results

The play-suppressant effects of amphetamine were antagonized by the alpha-2 adrenoreceptor antagonist RX821002 but not by the dopamine receptor antagonist alpha-flupenthixol. Remarkably, the effects of cocaine on social play were not antagonized by alpha-2 noradrenergic, dopaminergic or serotonergic receptor antagonists, administered either alone or in combination. The effects of a subeffective dose of cocaine were enhanced by a combination of subeffective doses of the serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine, the dopamine reuptake inhibitor GBR12909 and the noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine.

Conclusions

Amphetamine, like methylphenidate, exerts its play-suppressant effect through alpha-2 noradrenergic receptors. On the other hand, cocaine reduces social play by simultaneous increases in dopamine, noradrenaline and serotonin neurotransmission. In conclusion, psychostimulant drugs with different pharmacological profiles suppress social play behavior through distinct mechanisms. These data contribute to our understanding of the neural mechanisms of social behavior during an important developmental period, and of the deleterious effects of psychostimulant exposure thereon.

Keywords: Social play, Adolescence, Amphetamine, Cocaine, Dopamine, Serotonin, Noradrenaline, Alpha-2 adrenoceptor

Introduction

The young of many mammalian species, including humans, display a characteristic form of social interaction known as social play behavior or rough-and-tumble play (Panksepp et al. 1984; Vanderschuren et al. 1997; Pellis and Pellis, 2009). Social play behavior is of major importance for social and cognitive development (Potegal and Einon, 1989; Van den Berg et al. 1999; Baarendse et al. 2013). Furthermore, social play is highly rewarding. It is an incentive for maze learning, operant conditioning and place conditioning in rats and primates (for reviews see Vanderschuren 2010; Trezza et al. 2011) and it is modulated through neurotransmitter systems implicated in the positive subjective and motivational effects of food, sex and drugs of abuse (Trezza et al. 2010; Siviy and Panksepp, 2011). However, the underlying neurobiological mechanisms of social play behavior are still incompletely understood.

The abundance of social play behavior is an expression of the marked changes in social behavior that take place during post-weaning development (Spear, 2000; Nelson et al. 2005). Interestingly, the increased importance of interactions with peers during this phase of life (i.e., the juvenile and adolescent stages in rodents, roughly equivalent to childhood 0 and adolescence in humans) co-incides with other changes in behavior, such as increased risk-taking and experimenting with drugs of abuse (Casey and Jones, 2010; Blakemore and Robbins, 2012). Especially in the early stages of use, drugs are often experienced in a social setting (Boys et al. 2001; Newcomb and Bentler 1989), because of their presumed ability to facilitate interaction with peers, peer acceptance and group cohesion. However, drug use can have negative consequences for social behavior (for review, see Young et al. 2011). Therefore, investigating the effects of drugs of abuse on social play behavior serves two purposes. First, it increases our knowledge of the neural substrates of social play behavior. Second, it provides important information about how drugs of abuse affect the quality of social interactions during an important period of social development.

In rodent and primate studies, the psychostimulant drugs amphetamine, methylphenidate and cocaine have been shown to interfere with various social behaviors (Schiørring, 1979; Mizcek and Yoshimura, 1982; Beatty et al. 1982; -1984; Thor and Holloway, 1983; Sutton and Raskin, 1986; Ferguson et al. 2000; Vanderschuren et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2010). In particular, these psychostimulants profoundly decrease social play behavior in adolescent rats, without affecting general social interest (Beatty et al. 1982, 1984; Thor and Holloway, 1983; Sutton and Raskin, 1986; Ferguson et al. 2000; Vanderschuren et al. 2008). We have previously found that the play-suppressant effects of methylphenidate are mediated by stimulation of alpha-2 adrenoceptors, but that they are independent of dopaminergic neurotransmission (Vanderschuren et al. 2008). However, the mechanisms by which amphetamine and cocaine inhibit social play behavior are unknown (Beatty et al. 1984).

It is well established that amphetamine and cocaine increase the synaptic concentrations of dopamine, noradrenaline and serotonin (5-HT), by stimulating their release and inhibiting their reuptake, respectively (Heikkila et al. 1975; Ritz and Kuhar, 1989; Rothman et al. 2001). In addition, there is recent evidence to suggest that amphetamine and cocaine also facilitate exocytotic dopamine release (Venton et al. 2006; Aragona et al. 2008; Daberkow et al. 2013). The relative effectiveness of amphetamine and cocaine on monoamine neurotransmission differs, however. Whereas amphetamine preferentially enhances noradrenaline and dopamine neurotransmission, cocaine most profoundly inhibits the reuptake of 5-HT and dopamine (Ritz and Kuhar, 1989; Rothman et al. 2001). Therefore, we investigated the pharmacological mechanisms through which amphetamine and cocaine reduce social play behavior in rats. On the basis of our previous findings (Vanderschuren et al. 2008), and the pharmacological profiles of amphetamine and cocaine, we hypothesized that amphetamine suppresses social play through stimulation of alpha-2 adrenoceptors, but that the effect of cocaine on social play relies on dopamine and/or 5-HT mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) arrived in our animal facility at 21 days of age and were housed in groups of four in 40 × 26 × 20 cm (l x w x h) Macrolon cages under controlled conditions (temperature 20–21 °C, 55±15% relative humidity, and 12/12 h light cycle with lights on at 7.00 hours). Food and water were available ad libitum. All animals were experimentally naive and were used only once (i.e., different groups of rats were used for each experiment). All experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Utrecht University and were conducted in agreement with Dutch laws (Wet op de Dierproeven, 1996) and European regulations (Guideline 86/609/EEC).

Drugs

(+)-Amphetamine sulphate (0.05–0.5 mg/kg, s.c.) was obtained from O.P.G.(Utrecht, The Netherlands). Cocaine hydrochloride (0.5–7.5 mg/kg, s.c.), the dopamine receptor antagonist alpha-flupenthixol dihydrochloride (0.125 mg/kg, i.p.), the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY100635 maleate (0.1 mg/kg, s.c.), the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100907 (0.2 mg/kg, s.c.) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Schnelldorf, Germany). The alpha-2 adrenoreceptor antagonist RX821002 hydrochloride (0.2 mg/kg i.p.), the 5-HT2 receptor antagonist amperozide hydrochloride (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.), the 5-HT1/2 receptor antagonist methysergide maleate (2.0 mg/kg, s.c.) the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist ondansetron hydrochloride (2.0 mg/kg, i.p.), the 5-HT reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine hydrochloride (1–3 mg/kg, s.c.), the dopamine reuptake inhibitor GBR12909 dihydrochloride (3 mg/kg, s.c.) and the noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine hydrochloride (0.1–0.3 mg/kg, i.p.) were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Avonmouth, UK). All drugs were dissolved in saline, except for GBR12909 which was dissolved in sterile water and M100907 which was dissolved in saline containing 10% Tween 80 (Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany). Amphetamine and cocaine were injected 30 min before the test. The antagonists were administered 30 min before amphetamine or cocaine except for RX821002, which was administered 15 min before amphetamine and cocaine. The reuptake inhibitors were injected 30 min before the test.

We used doses of dopamine-, 5-HT- and noradrenaline receptor antagonists and reuptake-inhibitors that had no effect on social play by themselves (Homberg et al. 2007; Trezza and Vanderschuren 2008b; Vanderschuren et al. 2008). Drug doses and pretreatment intervals were based on our previous work, literature and pilot experiments. Solutions were freshly prepared on the day of the experiment and administered in a volume of 2 ml/kg. When an experiment involved a combination of antagonists or reuptake inhibitors, the different compounds were dissolved and injected separately to prevent interaction of two or more drugs in the same solution. Because of the importance of the neck area in the expression of social play behavior (Pellis and Pellis 1987; Siviy and Panksepp 1987), subcutaneous injections were administered in the flank.

Procedures

All behavioral procedures were conducted as previously described (Vanderschuren et al. 2008; Trezza et al. 2008a). Briefly, the experiments were performed in a sound attenuated chamber under dim light conditions. The testing arena consisted of a Plexiglas cage measuring 40 × 40 × 60 cm (l x w x h), with approximately 2 cm of wood shavings covering the floor. At 26–28 days of age, rats were individually habituated to the test cage for 10 min on each of the 2 days before testing. On the test day, the animals were socially isolated for 3.5 h before testing, to enhance their social motivation and thus facilitate the expression of social play behavior during testing. This isolation period has been shown to induce a half-maximal increase in the amount of social play behavior (Niesink and Van Ree 1989; Vanderschuren et al. 1995a; -2008). At the appropriate time before testing, pairs of animals were treated with drugs or vehicle. The test consisted of placing two animals into the test cage for 15 min. The animals in a pair did not differ more than 10 g in body weight. Since dominance status has a profound influence on the intensity and structure of social play (Pellis et al. 1997), and drug effects can be different in dominant versus subordinate animals (e.g. Panksepp et al. 1985; Knutson et al. 1996), animals in a test pair had no previous common social experience (i.e., they were not cage mates), to minimize the influence of dominance/subordination relationships on social play and the effects of drugs thereon. The behavior of the animals was videotaped and analysis from the video tape recordings was performed afterwards by an observer blind to treatment. Behavior was assessed per pair of animals using Observer 3.0 software (Noldus Information Technology BV, Wageningen, The Netherlands).

In rats, a bout of social play behavior starts with one rat soliciting (‘pouncing’) another animal, by attempting to nose or rub the nape of its neck. The animal that is pounced upon can respond in different ways: if the animal fully rotates to its dorsal surface, ‘pinning’ is the result, i.e., one animal lying with its dorsal surface on the floor with the other animal standing over it. From this position, the supine animal can initiate another play bout, by trying to gain access to the other animal’s neck. Thus, during social play, pouncing is considered an index of play solicitation, while pinning functions as a releaser of a prolonged play bout (Panksepp and Beatty 1980; Pellis and Pellis 1987; Poole and Fish 1975). Pinning and pouncing frequencies can be easily quantified and are considered the most characteristic parameters of social play behavior in rats (Panksepp and Beatty 1980; Trezza et al. 2010). During the social encounter, animals may also display social behaviors not directly associated with play, such as sniffing or grooming the partner’s body (Panksepp and Beatty, 1980; Vanderschuren et al. 1995). Since social play behavior in rats strongly depends on the playfulness of its partner (Pellis and McKenna 1992; Trezza and Vanderschuren 2008a), both animals in a play pair received the same drug treatment and a pair of animals was considered as one experimental unit. The following parameters were therefore scored per pair of animals:

-

Social behaviors related to play:

Frequency of pinning

Frequency of pouncing

-

Social behaviors unrelated to play:

Time spent in social exploration: the total amount of time spent in non playful forms of social interaction (i.e., one animal sniffing or grooming any part of the partner’s body).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. To assess the effects of single or combined treatments on social play behavior, data were analyzed using one- or two-way ANOVA. ANOVAs were followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test, where appropriate.

Results

The play-suppressant effects of amphetamine are mediated by activation of alpha-2 noradrenergic but not dopamine receptors

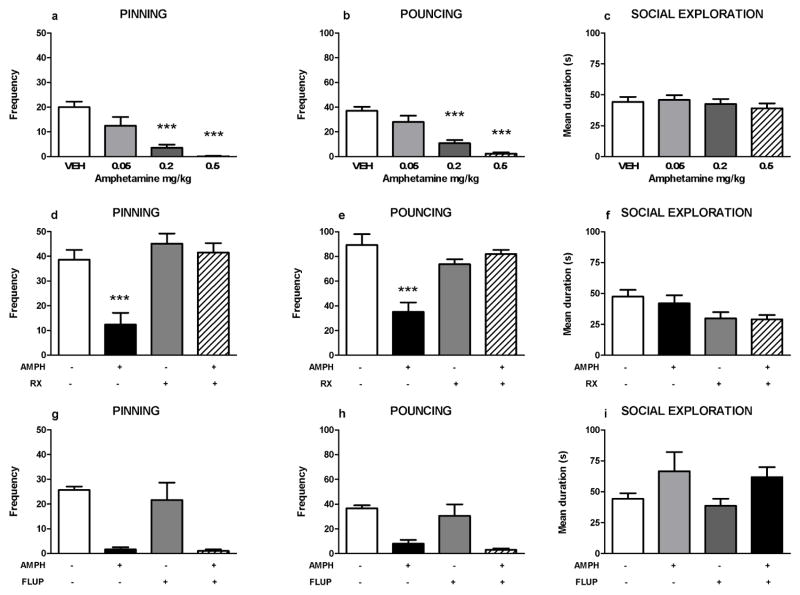

Amphetamine (amph; 0.2 and 0.5 mg/kg) significantly reduced pinning and pouncing, with no effect on social exploration (pinning: F(amph)3,28=16.58, p<0.001; pouncing F(amph)3,28=23.12, p<0.001; social exploration: F(amph)3,28=0.53, NS, figure 1a–c). We previously found that the reduction in social play behavior induced by treatment with methylphenidate was prevented by pretreatment with the alpha-2 adrenoceptor antagonist RX821002, but not the dopamine receptor antagonist alpha-flupenthixol (Vanderschuren et al. 2008). Therefore, we investigated whether RX821002 and alpha-flupenthixol altered the effect of the lowest effective dose of amphetamine (0.2 mg/kg) on social play. Pretreatment with RX821002 (0.2 mg/kg) blocked the effects of amphetamine on social play behavior (figure 1d–e). After saline pretreatment, amphetamine significantly reduced pinning and pouncing frequencies, whereas no significant differences between amphetamine- and vehicle-treated rats were found after pretreatment with RX821002 (pinning: F(RX)1,28=18.09, p<0.001; F(amph)1,28=12.72, p= 0.001; F(RX x amph)1,28=7.29, p= 0.01; pouncing: F(RX)1,28=5.94, p= 0.02; F(amph)1,28=12.86, p= 0.001; F(RX x amph)1,28=23.75, p<0.001). RX821002 reduced social exploration, but amphetamine did not influence this effect (social exploration: F(RX)1,28= 8.40, p= 0.01; F(amph)1,28=0.36, NS; F(RX x amph)1,28=0.21, NS; figure 1f). Pretreatment with alpha-flupenthixol (flup; 0.125 mg/kg) did not affect the reduction in pinning and pouncing induced by amphetamine (pinning: F(flup)1,20=0.42, NS; F(amph)1,20=38.57, p<0.001; F(flup x amph)1,20=0.22, NS); pouncing: F(flup)1,20=0.28, NS; F(amph)1,20=30.31, p<0.001; F(flup x amph)1,20=0.01, NS; figure 1g–h). In this experiment, amphetamine-treated rats spent more time in social exploration than vehicle-treated animals (social exploration: F(flup)1,20=0.30, NS; F(amph)1,20=5.71, p= 0.03; F(flup x amph)1,20=0.001, NS; figure 1i).

Figure 1.

Effect of noradrenergic and dopaminergic antagonists on amphetamine-induced suppression of social play behavior. Amphetamine (amph, s.c.) dose-dependently reduced pinning (a) and pouncing (b) without affecting social exploration (c). The effect of amphetamine (0.2 mg/kg) was blocked by the alpha-2 adrenoreceptor antagonist RX821002 (rx, 0.2 mg/kg, i.p.), pinning (d) pouncing (e) social exploration (f). The effect of amphetamine on pinning (g), pouncing (h) and social exploration (i) was not blocked by the dopamine antagonist alpha-flupenthixol (flup, 0.125 mg/kg, i.p.). Bars show the frequency (mean+SEM) of pinning and pouncing and the mean duration spent on social exploration (s) of the different treatment groups. + indicates couples of animals treated with the test compound, − indicates couples treated with the corresponding vehicle. N=6–8 couples per treatment group. One or two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test, ***p<0.001.

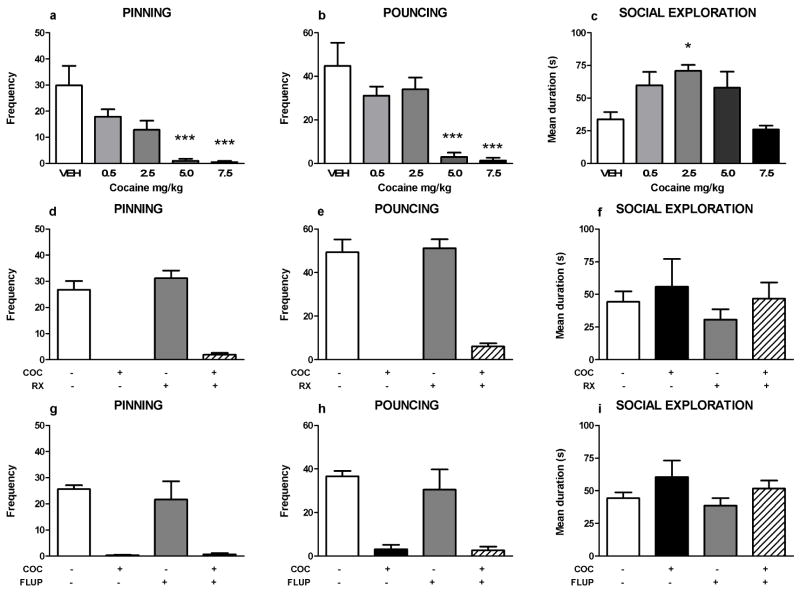

The play-suppressant effects of cocaine are not blocked by administration of dopamine, noradrenaline or 5-HT receptor antagonists

Cocaine (5.0–7.5 mg/kg) reduced pinning (F(coc)4,35=8.91, p<0.001) and pouncing (F(coc)4,35=10.12, p<0.001; figure 2a–b), whereas 2.5 mg/kg cocaine increased social exploration (F(coc)4,35=5.86, p=0.001; figure 2c). Since pretreatment with the RX821002, but not alpha-flupenthixol, blocked the effects of methylphenidate (Vanderschuren et al. 2008) and amphetamine (above) on social play, we next investigated whether these drugs also altered the effect of cocaine on social play. The reduction in social play induced by the lowest effective dose of cocaine (5.0 mg/kg) was not altered by pretreatment with RX821002 (0.2 mg/kg, pinning: F(RX)1,31=0.90, NS; F(coc)1,31=71.00, p<0.001; F(RX x coc)1,31=0.15, NS; pouncing: F(RX)1,31=0.90, NS; F(coc)1,31=76.78, p<0.001; F(RX x coc)1,31=0.16, NS; social exploration: F(RX)1,31=0.99, NS; F(coc)1,31=1.45, NS; F(RX x coc)1,31= 0.04, NS; figure 2d–f) or alpha-flupenthixol (0.125 mg/kg, pinning: F(flup)1,20=0.26, NS; F(coc)1,20=42.11, p<0.001; F(flup x coc)1,20=0.37, NS; pouncing: F(flup)1,20=0.45, NS; F(coc)1,20=37.66, p<0.001; F(flup x coc)1,20=0.32, NS; social exploration: F(flup)1,20=0.82, NS; F(coc)1,20=3.42, NS, F(flup x coc)1,20=0.85, NS; figure 2g–i).

Figure 2.

Effects of noradrenergic and dopaminergic antagonists on cocaine-induced suppression of social play behavior. Cocaine (coc, s.c.) dose-dependently suppressed pinning (a) and pouncing (b) and increased social exploration (c). The alpha-2 adrenoreceptor antagonist RX821002 (rx, 0.2 mg/kg, i.p.) and the dopamine receptor antagonist alpha-flupenthixol (flup, 0.125 mg/kg, i.p.) did not counteract the effects of cocaine (COC, 5 mg/kg) on pinning (d,g) and pouncing (e,h). Social exploration was unaffected by the treatments (f,i). Bars show the frequency of pinning and pouncing and the mean duration spent on social exploration (s) of the different treatment groups (mean+SEM). + indicates couples of animals treated with the test compound, − indicates couples treated with the corresponding vehicle. N=4–8 couples per treatment group. One or two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

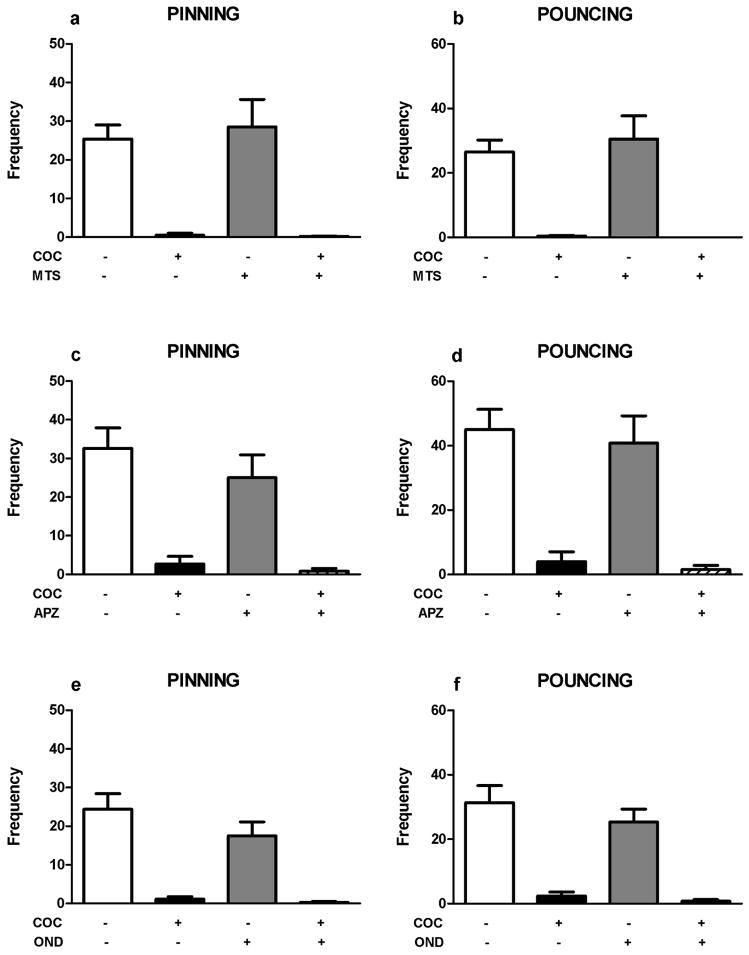

Next, we assessed the involvement of 5-HT receptor stimulation in the play-supressant effect of cocaine. Neither the 5-HT1/2 receptor antagonist methysergide (mts; 2 mg/kg, pinning: F(mts)1,28=0.30, NS; F(coc)1,28=44.00, p<0.001; F(mts x coc)1,28=0.19, NS; pouncing: F(mts)1,28=0.20, NS; F(coc)1,28=48.64, p<0.001; F(mts x coc)1,28=0.29, NS; figure 3a–b), nor the 5-HT2 receptor antagonist amperozide (apz; 0.5 mg/kg, pinning: F(apz)1,20=1.50, NS; F(coc)1,20=49.55, p<0.001; F(apz x coc)1,20=0.57, NS; pouncing: F(apz)1,20=0.40, NS; F(coc)1,20=58.62, p<0.001; F(apz x coc)1,20=0.03, NS; figure 3c–d), the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist ondansetron (ond; 1.0 mg/kg, pinning: F(ond)1,28=2.04, NS; F(coc)1,28=55.59, p<0.001; F(ond x coc)1,28=1.22, NS; pouncing: F(ond)1,28=1.27, NS; F(coc)1,28=62.68, p<0.001; F(ond x coc)1,28=0.42, NS; figure 3e–f), the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY100365 (way; 1 mg/kg, pinning: F(way)1,28=3.99, NS; F(coc)1,28=68.00, p<0.001; F(way x coc)1,28=3.50, NS; pouncing: F(way)1,28=2.66, NS; F(coc)1,28=96.05, p<0.001; F(way x coc)1,28=3.08, NS; figure 3g–h) or the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100907 (m100; 0.2 mg/kg, figure 3i–j) altered the effect of cocaine on social play, with no effect on social exploration (Table 1). M100907 itself reduced pinning (F(m100)1,28=4.77, p= 0.04; F(coc)1,28=17.26, p<0.001; F(m100 x coc)1,28=4.77, p= 0.04; figure 3i), but not pouncing (F(m100)1,28=1.98, NS; F(coc)1,31=37.71, p<0.001; F(m100 x coc)1,28= 0.81, NS; figure 3j) or social exploration (Table 1), whereas ondansetron altered social exploration (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Effects of 5-HT receptor antagonists on cocaine-induced suppression of social play behavior. 5-HT antagonists (methysergide: mts, 5HT1/2 antagonist, 2 mg/kg, s.c.; amperozide: apz, 5HT2 antagonist, 0.5 mg/kg, i.p.; ondansetron: ond, 5HT3 antagonist, 1.0 mg/kg, i.p.; WAY100365: way, 5HT1a antagonist, 0.1 mg/kg, s.c.; M100907: m100, 5HT2a antagonist, 0.2 mg/kg, s.c.) did not counteract the suppression of social play behavior induced by cocaine (coc, 5 mg/kg, s.c.): pinning (a,c,e,g,i), pouncing (b,d,f,h,j). Bars show the frequency (mean+SEM) of pinning and pouncing and the mean duration spent on social exploration (s) of the different treatment groups. + indicates couples of animals treated with the test compound, − indicates couples treated with the corresponding vehicle. N=5–8 couples per treatment group. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

Table 1.

Social exploration data and statistics

| Drug class | Drug | Mean ± SEM | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT antagonists | Methysergide (mts, 5HT1/2 antagonist, 2 mg/kg, s.c.) | veh-veh: 294,49 ± 35,13 veh-coc: 341,31 ± 22,99 mts-veh: 283,20 ± 28,67 mts-coc: 305,89 ± 39,85 |

F(mts)1,28=0.52, NS F(coc)1,28=1.16, NS F(mts x coc)1,28=0.14, NS |

| Amperozide (apz, 5HT2 antagonist, 0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) | veh-veh: 44,98 ± 11,88 veh-coc: 44,49 ± 7,75 apz-veh: 38,66 ± 6,23 apz-coc: 40,86 ± 7,32 |

F(apz)1,20=0.30, NS F(coc)1,20=0.01, NS F(apz x coc)1,20=0.02, NS |

|

| Ondansetron (ond, 5HT3 antagonist, 1.0 mg/kg, i.p.) | veh-veh: 212,67 ± 12,22 veh-coc: 274,41 ± 17,12 ond-veh: 239,98 ± 16,20 ond-coc: 219,10 ± 23,49 |

F(ond)1,28=5.43, p= 0.03 F(coc)1,28=1.33, NS F(ond x coc)1,28=0.62, NS |

|

| WAY100365 (way, 5HT1a antagonist, 0.1 mg/kg, s.c.) | veh-veh: 92,18 ± 10,94 veh-coc: 74,95 ± 8,15 way-veh: 70,17 ± 10,08 way-coc: 56,25 ± 13,29 |

F(way)1,28=3.12, NS F(coc)1,28=0.19, NS F(way x coc)1,28=0.02, NS |

|

| M100907 (m100, 5HT2a antagonist, 0.2 mg/kg, s.c.) | veh-veh: 147,70 ± 13,91 veh-coc: 137,75 ± 23,40 m100-veh: 186,13 ± 25,88 m100-coc: 105,48 ± 17,24 |

F(m100)1,28=0.02, NS F(coc)1,28=4.81, NS F(m100 x coc)1,28=2.93, NS |

|

| Combinations of antagonists |

RX821002 (rx, α2-adrenoreceptor antagonist, 0.2 mg/kg, i.p.) methysergide (meth, 5HT1/2 antagonist, 2 mg/kg, s.c.) |

veh-veh: 304,00 ± 25,72 veh-coc: 216,22 ±19,02 rx + meth-veh: 281,77 ± 29,44 rx + meth-coc: 281,28 ± 34,05 |

F(rx + meth)1,25=0.59, NS F(coc)1,25=2.51, NS F(rx + meth x coc)1,28=2.46, NS |

|

α-flupenthixo (flup, dopamine antagonist, 0.125 mg/kg, i.p.) methysergide (meth, 5HT1/2 antagonist, 2 mg/kg, s.c.) |

veh-veh: 282,61 ± 27,66 veh-coc: 267,1825 ± 21,71 flup + meth-veh: 314,69 ± 34,75 flup + meth-coc: 298,90 ± 27,10 |

F(flup + meth)1,28=1.28, NS F(coc)1,28=0.31, NS F(flup + meth x coc)1,28=0.00, NS |

|

|

RX821002 (rx, α2-adrenoreceptor antagonist, 0.2 mg/kg, i.p.) α-flupenthixol (flup, dopamine antagonist, 0.125 mg/kg, i.p.) methysergide (meth, 5HT1/2 antagonist, 2 mg/kg, s.c.) |

veh-veh: 291,49 ± 22,24 veh-coc: 264,89 ± 22,06 rx + flup + meth-veh: 326,00 ± 41,38 rx + flup + meth-coc: 368,29 ± 43,57 |

F(rx + flup + meth)1,28=4.14, NS F(coc)1,28=0.05, NS F(rx + flup + meth x coc)1,28=1.03, NS |

|

| Combinations of reuptake inhibitors | fluoxetine (f3, SSRI*, 3 mg/kg, s.c.) | veh-veh: 243,06 ± 27,31 veh-coc: 339,91 ± 20,70 f3-veh: 319,86 ± 39,745 f3-coc: 322,99 ± 31,36 |

F(f3)1,27=3.40, NS F(coc)1,27=1.79, NS F(f3 x coc)1,27=0.65, NS |

|

fluoxetine (f3, SSRI, 3 mg/kg, s.c.) GBR12909 (g3, DARI# 3 mg/kg, s.c.) |

veh-veh: 241,31 ± 19,18 veh-coc: 256,80 ± 20,32 f3 + g3-veh: 270,42 ± 35,49 f3 + g3-coc: 282,83 ± 26,07 |

F(f3 + g3)1,28=1.12, NS F(coc)1,28=0.29, NS F(f3 + g3 x coc)1,28=0.00, NS |

|

|

fluoxetine (f3, SSRI, 3 mg/kg, s.c.) GBR12909 (g3, DARI 3 mg/kg) atomoxetine (a0.1, NARI$, 0.1 mg/kg, i.p.) |

veh-veh: 291,49 ± 20,80 veh-coc: 264,89 ± 20,64 f3 + g3 + a0.1-veh: 326,00 ± 38,70 f3 + g3 + a0.1-coc: 368,29 ± 40,76 |

F(f3 + g3 + a0.1)1,26=9.35, p= 0.01 F(coc)1,26= 0.03, p= NS F(f3 + g3 + a0.1 x coc)1,26=1.85, p= NS |

SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor,

DARI: dopamine reuptake inhibitor,

NARI: noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor.

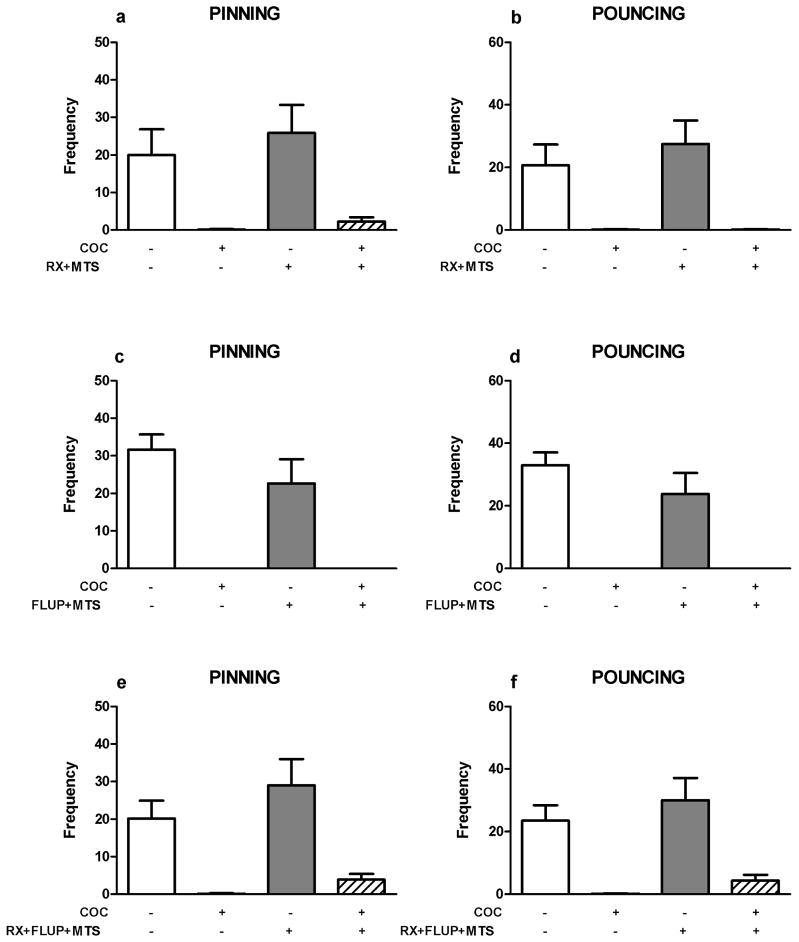

We then hypothesized that the effect of cocaine is mediated by redundant monoaminergic mechanisms. To test this possibility, we investigated the effect of pretreatment with combinations of two or three monoamine receptor antagonists on the play-suppressant effect of cocaine. Pretreatment with a combination of RX821002 (0.2 mg/kg) and methysergide (2 mg/kg, figure 4a–b), a combination of alpha-flupenthixol (0.125 mg/kg,) and methysergide (2 mg/kg, figure 4c–d), or a combination of RX821002 (0.2 mg/kg), alpha-flupenthixol (0.125 mg/kg) and methysergide (2 mg/kg, figure 4e–f) did not affect the reduction in pinning (F(mts + rx)1,25=0.57, NS; F(coc)1,25=16.59, p<0.001; F(mts + rx x coc)1,25=0.12, NS; F(flup + mts)1,28=1.39, NS; F(coc)1,28=50.56, p<0.001; F(flup + mts x coc)1,28=1.39, NS; F(rx + flup + mts)1,28=0.15, NS; F(coc)1,28=27.47, p<0.001; F(rx + flup + mts x coc)1,28=0.35, NS) and pouncing (F(mts + rx)1,25=0.82, NS; F(coc)1,25=17.99, p<0.001; F(mts + rx x coc)1,25=0.14, NS; F(flup + mts)1,28=1.37, NS; F(coc)1,20=51.51, p<0.001; F(flup + mts x coc)1,28=1.37, NS; F(rx + flup + mts)1,28=1.47, NS; F(coc)1,28=30.57, p<0.001; F(rx + flup + mts x coc)1,28=0.06, NS), induced by cocaine (5.0 mg/kg). These drug combinations did not affect social exploration (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Effects of combinations of monoaminergic antagonists on the play suppressant effects of cocaine (coc, 5 mg/kg, s.c.). A combination of RX821002 (rx, α2-adrenoreceptor antagonist, 0.2 mg/kg, i.p.) + methysergide (mts, 5-HT1/2 receptor antagonist, 2 mg/kg, s.c.), a combination of α-flupenthixol (flup, dopamine receptor antagonist, 0.125 mg/kg, i.p.) + methysergide (mts, 5-HT1/2 receptor antagonist, 2 mg/kg, s.c.) and a combination of RX821002 (rx, α2-adrenoreceptor antagonist, 0.2 mg/kg, i.p.) + α-flupenthixol (flup, dopamine receptor antagonist, 0.125 mg/kg, i.p.) + methysergide (mts, 5-HT1/2 receptor antagonist, 2 mg/kg, s.c.) did not antagonize the reduction in pinning (a,c,e) and pouncing (b,d,f) induced by cocaine. Bars show the frequency (mean+SEM) of pinning and pouncing and the mean duration spent on social exploration (s) of the different treatment groups. + indicates couples of animals treated with the test compounds, − indicates couples treated with the corresponding vehicles, N=7–8 couples per treatment group.

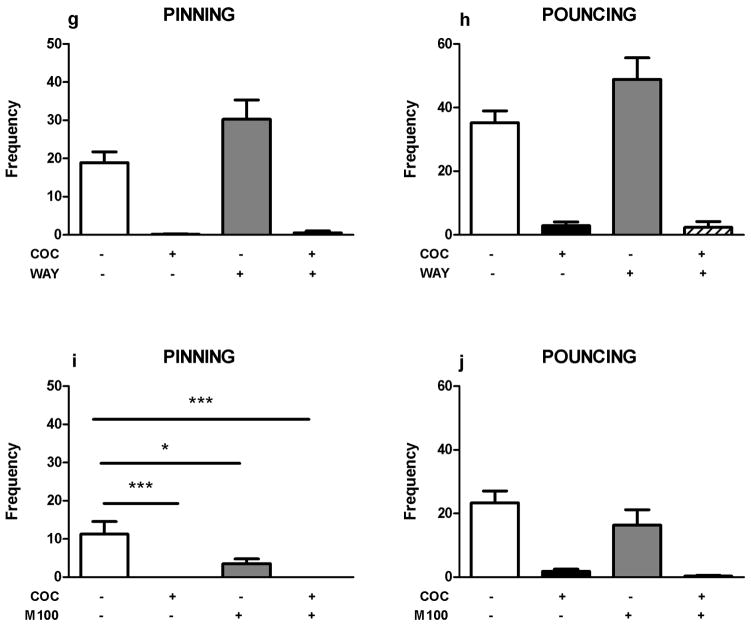

The play-suppressant effects of cocaine are mediated by simultaneous blockade of dopamine, noradrenaline and 5-HT neurotransmission

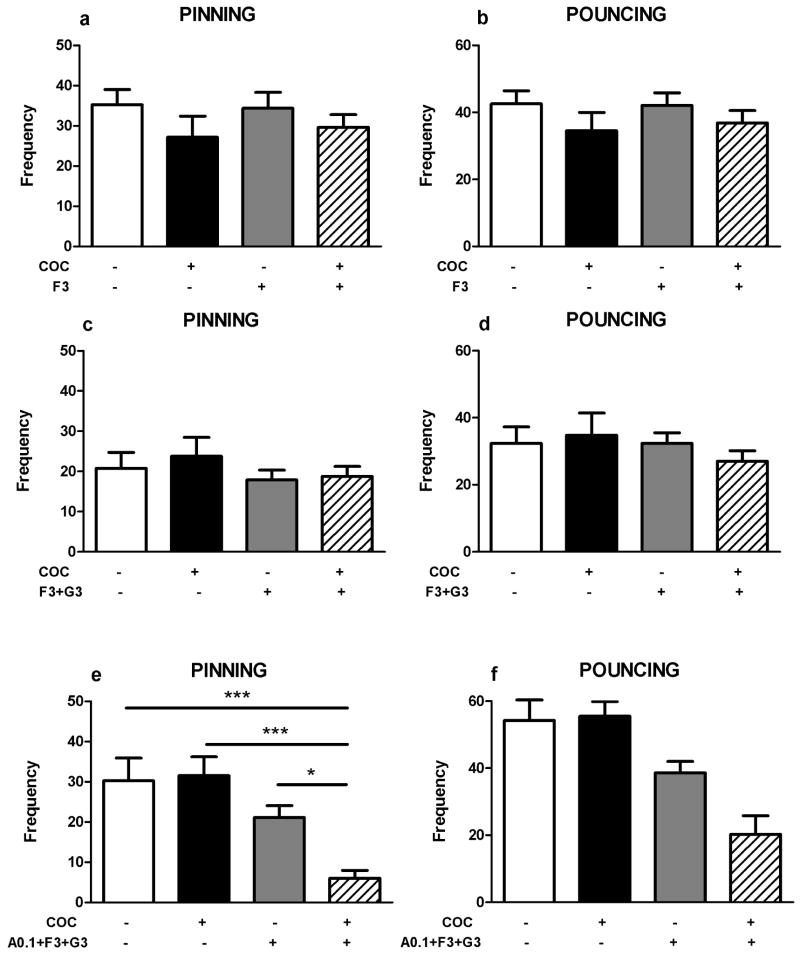

The data presented in figures 2–4 did not identify the dopamine, noradrenaline or 5-HT receptor mechanism through which cocaine exerts its effect on social play. To test whether monoamine reuptake is at all involved in the effect of cocaine, we investigated the effects of combined subeffective doses of cocaine and monoamine reuptake inhibitors on social play. The effect of a subeffective dose of cocaine (0.5 mg/kg) on pinning and pouncing was not changed by treatment with either a subeffective dose of the 5-HT reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine (f3; 3 mg/kg, pinning: F(f3)1,27=2.44, NS; F(coc)1,27=0.04, NS; F(f3 x coc)1,28=0.17, NS; pouncing: F(f3)1,27=2.41, NS; F(coc)1,28=0.05, NS; F(f3 x coc)1,27=0.11, NS; figure 5a–b), or by a combination of subeffective doses of the 5-HT reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine (3 mg/kg) and the dopamine reuptake inhibitor GBR12909 (g3; 3 mg/kg, pinning: F(f3 + g3)1,28=0.30, NS; F(coc)1,28=1.23, NS; F(f3 + g3 x coc)1,28=0.09, NS; pouncing: F(f3 + g3)1,28=0.10, NS; F(coc)1,28=0.68, NS; F(f3 + g3 x coc)1,28=0.68, NS; figure 5c–d). Combined administration of fluoxetine, GBR12909 and the noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine (a0.1; 0.1 mg/kg) reduced pinning (F(f3 + g3 + a0.1)1,26=20.08, p<0.001; F(coc)1,26=3.23, NS) and pouncing (F(f3 + g3 + a0.1)1,26=23.72, p<0.001; F(coc)1,26=2.67, NS; F(f3 + g3 + a0.1 x coc)1,26=3.51, NS), and increased social exploration (Table 1). Importantly, a significant interaction between the combination of reuptake inhibitors and a subeffective dose of cocaine was found for pinning (F(f3 + g3 + a0.1 x coc)1,26=4.46, p= 0.05; figure 5e–f). Post-hoc analyses revealed that pinning was reduced in animals treated with the reuptake inhibitors plus a subeffective dose of cocaine compared to the other groups (figure 5e). These results suggest that combined blockade of the reuptake of dopamine, noradrenaline and 5-HT underlies the effect of cocaine on social play behavior in rats.

Figure 5.

Effect of (combinations of) subeffective doses of monoamine reuptake inhibitors and a subeffective dose of cocaine on social play. Combined administration of a subeffective dose of fluoxetine (f3, serotonin reuptake inhibitor, 3 mg/kg, s.c.) and a subeffective dose of cocaine (coc, 0.5 mg/kg, s.c.) or combined administration of a subeffective dose of fluoxetine (f3, serotonin reuptake inhibitor, 3 mg/kg, s.c.) and GBR12909 (g3, dopamine reuptake inhibitor, 3 mg/kg, s.c.) together with a subeffective dose of cocaine (coc, 0.5 mg/kg, s.c.) had no effects on pinning (a,c) and pouncing (b,d). Combined administration of a subeffective dose of fluoxetine (f3, serotonin reuptake inhibitor, 3 mg/kg, s.c.) + GBR12909 (g3, dopamine reuptake inhibitor, 3 mg/kg) + atomoxetine (a0.1, noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, 0.1 mg/kg, i.p.) together with a subeffective dose of cocaine (COC, 0.5 mg/kg, s.c.) significantly reduced pinning (e) but not pouncing (f). Bars show the frequency (mean±SEM) of pinning and pouncing and the mean duration spent on social exploration (s) of the different treatment groups. + indicates couples of animals treated with the test compounds, − indicates couples treated with the corresponding vehicles. N=6–8 couples per treatment group. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

Discussion

The present study investigated the pharmacological mechanisms underlying the effects of amphetamine and cocaine on social play behavior. We found that low doses of amphetamine and cocaine suppressed social play behavior in adolescent rats. These effects were behaviorally specific, since both psychostimulants did not consistently alter social exploratory behavior. The effects of amphetamine on social play depended on alpha-2 noradrenaline but not dopamine receptors. In contrast, the effects of cocaine on social play depended on simultaneous increases in dopamine, noradrenaline and 5-HT neurotransmission.

We have previously shown that the reduction in social play induced by the dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor methylphenidate was reversed by pretreatment with the alpha-2 adrenoceptor antagonist RX821002, but not the alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonist prazosine, the beta adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol or the dopamine receptor antagonist alpha-flupenthixol. Furthermore, the play-suppressant effect of methylphenidate was mimicked by the selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine but not by the selective dopamine reuptake inhibitor GBR12909 or the dopamine receptor agonist apomorphine (Vanderschuren et al. 2008). In line with these findings, the play-suppressant effects of amphetamine were blocked by RX821002, but not alpha-flupenthixol. These findings are consistent with previous observations that the dopamine receptor antagonist haloperidol, the alpha-1 adrenoreceptor antagonist phenoxybenzamine, the beta adrenoreceptor antagonist propranolol and the combined alpha-1 and dopamine D2 receptor antagonist chlorpromazine were ineffective in counteracting the effects of amphetamine on social play behavior (Beatty et al. 1984), and that haloperidol and chlorpromazine did not counteract the disruptive effects of amphetamine and cocaine on social behavior in primates (Miczek and Yoshimura 1982). Together, these data show that the play suppressant effects of amphetamine, like methylphenidate, are mediated by activation of alpha-2 adrenoreceptors, and are independent of dopaminergic neurotransmission.

Cocaine inhibits the reuptake of dopamine, 5-HT and, to a lesser extent, noradrenaline (Heikkila et al. 1975; Ritz and Kuhar 1989; Rothman et al. 2001). We found that administration of the dopamine receptor antagonist alpha-flupenthixol, the alpha-2 adrenoreceptor antagonist RX821002 or the 5-HT receptor antagonists amperozide (5-HT2), methysergide (5-HT1/2), ondansetron (5-HT3), WAY100365 (5-HT1A) and M100907 (5-HT2A) did not antagonize the reduction in social play behavior induced by cocaine, indicating that it is not likely that one single monoamine receptor mechanism underlies this effect of cocaine. In keeping with these findings, it has previously been found that the reduction in social interaction induced by cocaine in rats was not antagonized by pretreatment with amperozide (Rademacher et al. 2002), and that cocaine-induced social deficits in primates were not altered by pretreatment with chlorpromazine or haloperidol (Miczek and Yoshimura 1982). Interestingly, combinations of methysergide and RX821002, methysergide and alpha-flupenthixol, or a combination of methysergide, RX821002 and alpha-flupenthixol did not counteract the effect of cocaine on social play, which suggests that the play-suppressant effect of cocaine is not exerted through redundant monoamine receptor mechanisms. Since at least 14 subtypes of 5-HT receptors exist (Boess and Martin 1994), the possibility remains that a combination of drugs antagonizing different 5-HT receptors is effective in counteracting the play-suppressant effects of cocaine. To identify which monoamines were involved in the effects of cocaine on social play, we tested the effects of subeffective doses of monoamine reuptake inhibitors administered in combination with a subeffective dose of cocaine. We found that a combination of subeffective doses of the dopamine, noradrenaline and serotonin reuptake inhibitors GBR12909, atomoxetine and fluoxetine modestly reduced social play, which was potentiated by a subeffective dose of cocaine. However, fluoxetine alone or a combination of fluoxetine and GBR12909 were ineffective, and co-administration of a subeffective dose of cocaine with either fluoxetine or fluoxetine plus GBR12909 did not reduce social play either. Since cocaine has much lower affinity for the noradrenaline transporter than for the dopamine or 5-HT transporter (Ritz and Kuhar, 1989; Rothman et al. 2001), we did not test the effects of atomoxetine combined with fluoxetine, GBR12909 and/or cocaine. We have previously shown that atomoxetine and fluoxetine, at doses higher than those used here, reduced play behavior, while GBR12909 did not alter social play (Homberg et al. 2007; Vanderschuren et al. 2008). Together, these findings suggest that simultaneous increases in synaptic concentrations of all three monoamines underlie the inhibitory effect of cocaine on social play behavior, although the specific receptors involved remain to be elucidated. Intracranial infusion studies may be helpful in clarifying the mechanism of action by which cocaine inhibits social play behavior.

Social play behavior is a highly vigorous form of social behavior with a strong locomotor component (Panksepp et al. 1984; Vanderschuren et al. 1997; Pellis and Pellis 2009), and amphetamine and cocaine are known to evoke locomotor hyperactivity (Wise and Bozarth 1987). It may therefore be that the psychostimulant-induced suppression of play is the result of behavioral competition, i.e. that the exaggerated hyperactivity induced by amphetamine and cocaine prevents the animals from engaging in a meaningful social interaction. However, we think that this possibility is unlikely, for two reasons. First, the reduction in social play behavior was induced by lower doses of amphetamine and cocaine than those typically used to induced psychomotor hyperactivity (e.g. Sahakian et al. 1975; White et al. 1998), even when taking into account that the sensitivity to psychostimulant drugs may be different for periadolescent vs adult rats (for review see Schramm-Sapyta et al. 2009). Second, the psychomotor hyperactivity induced by amphetamine and cocaine strongly depends on dopaminergic neurotransmission (e.g. Kelly et al. 1975; White et al. 1998), whereas their effects on social play behavior are dopamine-independent (Beatty et al. 1984; Vanderschuren et al. 2008; present study). Third, we have previously shown that the effects of methylphenidate on social play and its psychomotor stimulant effects can be dissociated (Vanderschuren et al. 2008).

One may argue that the play-suppressant effects of amphetamine and cocaine reflect an occlusion of social reward. Thus, the positive subjective effects of the psychostimulants could substitute for rewarding effects of social play, so that the animals would no longer need to seek out a social source of positive emotions. Along similar lines, it has been suggested that amphetamine may substitute for the rewarding effects of pair bond formation in prairie voles, and vice versa (Liu et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2011). We do not think that this is the explanation for the present findings, however, for two reasons. First, whereas the rewarding effects of psychostimulant drugs rely on dopaminergic mechanisms (e.g. Veeneman et al. 2011; Veeneman et al. 2012; for reviews see Wise 2004; Pierce and Kumaresan 2006), their effects on social play do not. Second, non-psychostimulant drugs of abuse, such as opiates, nicotine and ethanol, as well as drugs that enhance endocannabinoid signaling actually enhance social play (for reviews see Trezza et al. 2010; Siviy and Panksepp 2011). It would then be difficult to conceive why some euphorigenic drugs increase, whereas other reduce social play, if their positive subjective effects would substitute for those of social play behavior.

An alternative interpretation of the play-suppressant effect of amphetamine and cocaine is that these psychostimulants are anxiogenic (File and Seth, 2003). However, amphetamine and cocaine did not affect social exploratory behavior, which is the standard parameter used in the social interaction test of anxiety (File and Seth, 2003). Moreover, pharmacological analysis of social play behavior has consistently shown that anxiolytic or anxiogenic drugs do not invariably increase or reduce social play, respectively (Vanderschuren et al. 1997). On the contrary, our recent experiments have shown that doses of nicotine and ethanol, that increase social play in both familiar and unfamiliar environments, did not affect anxiety as tested on the elevated plus maze. Conversely, the standard anxiolytic drug diazepam, which did have an anxiolytic effect on the elevated plus maze, reduced social play, but increased social exploration (Trezza et al. 2009). Thus, it is highly unlikely that the reduction in social play induced by cocaine and amphetamine is secondary to an anxiogenic effect of these drugs.

Several hypotheses can be put forward to explain the effects of psychostimulants on social play behavior. First, on the basis of their effectiveness in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and the comparable pharmacological profile of the effects of amphetamine and methylphenidate on social play behavior (Vanderschuren et al. 2008; present study) and the stop signal task (Eagle and Baunez 2010), it can be hypothesized that the play suppressant effects of psychostimulants are the result of enhanced or exaggerated behavioral inhibition. That is, through increasing inhibitory control over behavior, psychostimulant drugs may enhance attention for non-social stimuli in the environment, causing the animals to engage less in vigorous playful interactions, that are accompanied by reduced attention for, potentially important, environmental stimuli. Second, and in contrast, psychostimulant-induced increases in tonic noradrenergic neurotransmission may promote disengagement from ongoing (playful) behaviors and facilitate the switching of behaviors (Aston-Jones and Cohen 2005). This may impact social play behavior, that requires appropriate behavioral responses from both partners of a dyad. Third, the play suppressant effect of psychostimulants can be explained by the notion that they increase the intensity of behavior. As not all behaviors can be intensified to the same degree, this causes a narrowing down of the behavioral repertoire with simple behaviors being favored over complex behaviors, such as social play (Lyon and Robbins 1975). One needs to bear in mind though, that the present findings add a layer of complexity over the possible behavioral mechanisms of psychostimulant-induced suppression of social play. That is, since amphetamine and methylphenidate reduce social play through a distinct pharmacological mechanism of action than cocaine does, it is well conceivable that the behavioral underpinnings of these effects also differ between different psychostimulant drugs. In this regard, it is worth mentioning that amphetamine and cocaine suppressed pouncing (i.e. play solicitation) and pinning (the most prominent response to pouncing in rats this age, i.e. response to play solicitation) with comparable potency. This is somewhat in contrast with a previous study that showed that amphetamine affects pouncing at lower doses than responding to pouncing by rotating to supine (i.e. pinning) (Field and Pellis 1994). It may therefore well be that subcomponents of social play (i.e. pouncing, and the different possible defense strategies) are also differentially affected by amphetamine and cocaine.

In summary, we show here that amphetamine, like methylphenidate, exerts its play-suppressant effect through stimulation of alpha-2 adrenoreceptors. Cocaine, on the other hand, exerts its effect through simultaneous increases in dopamine, noradrenaline and 5-HT neurotransmission. Positive social interactions in young individuals are essential for emotional well-being and for social and cognitive development. Moreover, the inability to assign a positive subjective value to social stimuli may be a key process in the pathophysiology of childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders characterized by aberrant social interactions. Our present study advances our understanding of how psychostimulant drugs negatively impact upon social interactions in young individuals. This work has relevance for our understanding of the neural mechanisms of normal social development, as well as childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders with a prominent social dimension, such as autism, disruptive behavior disorders and schizophrenia. Moreover, given the emergence of drug use during early adolescence, increasing our understanding of how psychostimulant drugs affect social behavior has obvious repercussions for the etiology of substance abuse.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01 DA022628 (L.J.M.J.V.), Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) Veni grant 91611052 (V.T.) and Marie Curie Career Reintegration Grant PCIG09-GA-2011-293589 (V.T.).

References

- Aragona BJ, Cleaveland NA, Stuber GD, Day JJ, Carelli RM, Wightman RM. Preferential enhancement of dopamine transmission within the nucleus accumbens shell by cocaine is attributable to a direct increase in phasic dopamine release events. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8821–8831. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2225-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: Adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baarendse PJJ, Counotte DS, O’Donnell P, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Early social experience is critical for the development of cognitive control and dopamine modulation of prefrontal cortex function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty WW, Costello KB, Berry SL. Suppression of play fighting by amphetamine: effects of catecholamine antagonists, agonists and synthesis inhibitors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1984;20:47–755. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(84)90194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty WW, Dodge AM, Dodge LJ, Panksepp J. Psychomotor stimulants, social deprivation and play in juvenile rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;16:417–422. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boess FG, Martin IL. Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:275–317. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boys A, Marsden J, Strang J. Understanding reasons for drug use amongst young people: a functional perspective. Health Educ Res. 2001;16:457–469. doi: 10.1093/her/16.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM. Neurobiology of the adolescent brain and behavior: implications for substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1189–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daberkow DP, Brown HD, Bunner KD, Kraniotis SA, Doellman MA, Ragozzino ME, Garris PA, Roitman MF. Amphetamine paradoxically augments exocytotic dopamine release and phasic dopamine signals. J Neurosci. 2013;33:452–463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2136-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle DM, Baunez C. Is there an inhibitory-response-control system in the rat? Evidence from anatomical and pharmacological studies of behavioral inhibition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:50–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SA, Frisby NB, Ali SF. Acute effects of cocaine on play behaviour of rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2000;11:175–179. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200004000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field EF, Pellis SM. Differential effects of amphetamine on the attack and defense components of play fighting in rats. Physiol Behav. 1994;56:325–330. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File SE, Seth P. A review of 25 years of the social interaction test. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463:35–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila RE, Orlansky H, Mytilineou C, Cohen G. Amphetamine: evaluation of d- and l-isomers as releasing agents and uptake inhibitors for 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine in slices of rat neostriatum and cerebral cortex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;194:47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homberg JR, Schiepers OJG, Schoffelmeer ANM, Cuppen E, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Acute and constitutive increases in central serotonin levels reduce social play behaviour in peri-adolescent rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;195:175–182. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0895-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys AP, Einon DF. Play as a reinforcer for maze-learning in juvenile rats. Anim Behav. 1981;29:259–270. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Panksepp J, Pruitt D. Effects of fluoxetine on play dominance in juvenile rats. Aggr Behav. 1996;22:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Aragona BJ, Young KA, Dietz DM, Kabbaj M, Mazei-Robison M, Nestler EJ, Wang Z. Nucleus accumbens dopamine mediates amphetamine-induced impairment of social bonding in a monogamous rodent species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1217–1222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911998107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Young KA, Curtis JT, Aragona BJ, Wang Z. Social bonding decreases the rewarding properties of amphetamine through a dopamine D1 receptor-mediated mechanism. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7960–7966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1006-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon M, Robbins TW. The action of central nervous system stimulant drugs: A general theory concerning amphetamine effects. In: Essman WB, Valzelli L, editors. Current developments in psychopharmacology. Vol. 2. Spectrum; New York: 1975. pp. 79–163. [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Yoshimura H. Disruption of primate social behavior by d-amphetamine and cocaine: differential antagonism by antipsychotics. Psychopharmacology. 1982;76:163–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00435272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EE, Leibenluft E, McClure EB, Pine DS. The social re-orientation of adolescence: a neuroscience perspective on the process and its relation to psychopathology. Psychol Med. 2005;35:163–174. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Substance use and abuse among children and teenagers. Am Psy. 1989;44:242–248. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesink RJM, Van Ree JM. Involvement of opioid and dopaminergic systems in isolation-induced pinning and social grooming of young rats. Neuropharmacology. 1989;28:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(89)90038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normansell L, Panksepp J. Effects of morphine and naloxone on play-rewarded spatial discrimination in juvenile rats. Dev Psychobiol. 1990;23:75–83. doi: 10.1002/dev.420230108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J, Siviy S, Normansell L. The psychobiology of play: theoretical and methodological perspectives. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1984;8:465–492. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J, Beatty WW. Social deprivation and play in rats. Behav Neural Biol. 1980;30:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(80)91077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J, Jalowiec J, DeEskinazi FG, Bishop P. Opiates and play dominance in juvenile rats. Behav Neurosci. 1985;99:441–453. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.99.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis SM, McKenna MM. Intrinsic and extrinsic influences on play fighting in rats: effects of dominance, partner’s playfulness, temperament and neonatal exposure to testosterone propionate. Behav Brain Res. 1992;50:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis SM, Field EF, Smith LK, Pellis VC. Multiple differences in the play fighting of male and female rats. Implications for the causes and functions of play. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:105–120. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis SM, Pellis VC. Play-fighting differs from serious fighting in both target of attack and tactics of fighting in the laboratory rat Rattus norvegicus. Aggress Behav. 1987;13:227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Pellis SM, Pellis VC. The playful brain: venturing to the limits of neuroscience. Oneworld Publications; Oxford: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Kumaresan V. The mesolimbic dopamine system: the final common pathway for the reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:215–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole TB, Fish J. Investigation of playful behavior in Rattus norvegicus and Mus musculus (Mammalia) J Zool. 1975;175:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Potegal M, Einon D. Aggressive behaviors in adult rats deprived of playfighting experience as juveniles. Dev Psychobiol. 1989;22:159–172. doi: 10.1002/dev.420220206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher DJ, Schuyler AL, Kruschel CK, Steinpreis RE. Effects of cocaine and putative atypical antipsychotics on rat social behavior. An ethopharmacological study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00904-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Kuhar MJ. Relationship between self-administration of amphetamine and monoamine receptors in brain: comparison with cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248:1010–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, et al. Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin. Synapse. 2001;39:32–41. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW, Morgan MJ, Iversen SD. The effects of psychomotor stimulants on stereotypy and locomotor activity in socially-deprived and control rats. Brain Res. 1975;84:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90975-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiørring E. Social isolation and other behavioral changes in groups of adult vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) produced by low, nonchronic doses of d-amphetamine. Psychopharmacology. 1979;64:297–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00427513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm-Sapyta NL, Walker QD, Caster JM, Levin ED, Kuhn CM. Are adolescents more vulnerable to drug addiction than adults? Evidence from animal models. Psychopharmacology. 2009;206:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1585-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy SM, Panksepp J. Sensory modulation of juvenile play in rats. Dev Psychobiol. 1987;20:39–55. doi: 10.1002/dev.420200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy SM, Panksepp J. In search of the neurobiological substrates for social playfulness in mammalian brains. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1821–1830. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton ME, Raskin LA. A behavioral analysis of the effects of amphetamine on play and locomotor activity in the post-weaning rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;24:455–461. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90541-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor DH, Holloway WR., Jr Play soliciting in juvenile male rats: effects of caffeine, amphetamine and methylphenidate. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1983;19:725–727. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Cannabinoid and opioid modulation of social play behavior in adolescent rats: Differential behavioral mechanisms. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008a;18:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Bidirectional cannabinoid modulation of social behavior in adolescent rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008b;197:217–227. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Baarendse PJJ, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Prosocial effects of nicotine and ethanol in adolescent rats through partially dissociable neurobehavioral mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2560–2573. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Baarendse PJJ, Vanderschuren LJMJ. The pleasures of play: Pharmacological insights into social reward mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Campolongo P, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Evaluating the rewarding nature of social interactions in laboratory animals. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2011;1:444–458. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg CL, Pijlman FT, Koning HA, Diergaarde L, Van Ree JM, Spruijt BM. Isolation changes the incentive value of sucrose and social behaviour in juvenile and adult rats. Behav Brain Res. 1999;106:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJMJ, Niesink RJM, Spruijt BM, Van Ree JM. Effects of morphine on different aspects of social play in juvenile rats. Psychopharmacology. 1995a;117:225–231. doi: 10.1007/BF02245191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJMJ, Spruijt BM, Hol T, Niesink RJM, Van Ree JM. Sequential analysis of social play behavior in juvenile rats: effects of morphine. Behav Brain Res. 1995b;72:89–95. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJMJ, Niesink RJM, Van Ree JM. The neurobiology of social play behavior in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:309–326. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJMJ, Trezza V, Griffioen-Roose S, Schiepers OJG, Van Leeuwen N, De Vries TJ, et al. Methylphenidate disrupts social play behavior in adolescent rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2946–2956. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJMJ. How the brain makes play fun. Am J Play. 2010;2:315–337. [Google Scholar]

- Veeneman MMJ, Boleij H, Broekhoven MH, Snoeren EMS, Guitart Masip M, Cousijn J, Spooren W, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Dissociable roles of mGlu5 and dopamine receptors in the rewarding and sensitizing properties of morphine and cocaine. Psychopharmacology. 214:863–876. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2095-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeneman MMJ, Broekhoven MH, Damsteegt R, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Distinct contributions of dopamine in the dorsolateral striatum and nucleus accumbens shell to the reinforcing properties of cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:487–498. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venton BJ, Seipel AT, Phillips PEM, Wetsel WC, Gitler D, Greengard P, Augustine GJ, Wightman RM. Cocaine increases dopamine release by mobilization of a synapsin-dependent reserve pool. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3206–3209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4901-04.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White FJ, Joshi A, Koeltzow TE, Hu XT. Dopamine receptor antagonists fail to prevent induction of cocaine sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18:26–40. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Bozarth MA. A psychomotor stimulant theory of addiction. Psychol Rev. 1987;94:469–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:483–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KA, Gobrogge KL, Wang Z. The role of mesocorticolimbic dopamine in regulating interactions between drugs of abuse and social behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:498–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]