Abstract

Purpose

To describe the clinical and molecular findings of an Italian family with a new mutation in the choroideremia (CHM) gene.

Methods

We performed a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination, fundus photography, macular optical coherence tomography, perimetry, electroretinography, and fluorescein angiography in an Italian family. The clinical diagnosis was supported by western blot analysis of lymphoblastoid cell lines from patients with CHM and carriers, using a monoclonal antibody against the 415 C-terminal amino acids of Rab escort protein-1 (REP-1). Sequencing of the CHM gene was undertaken on genomic DNA from affected men and carriers; the RNA transcript was analyzed with reverse transcriptase-PCR.

Results

The affected men showed a variability in the rate of visual change and in the degree of clinical and functional ophthalmologic involvement, mainly age-related, while the women displayed aspecific areas of chorioretinal degeneration. Western blot did not show a detectable amount of normal REP-1 protein in affected men who were hemizygous for a novel mutation, c.819+2T>A at the donor splicing site of intron 6 of the CHM gene; the mutation was confirmed in heterozygosity in the carriers.

Conclusions

Western blot of the REP-1 protein confirmed the clinical diagnosis, and molecular analysis showed the new in-frame mutation, c.819+2T>A, leading to loss of function of the REP-1 protein. These results emphasize the value of a diagnostic approach that correlates genetic and ophthalmologic data for identifying carriers in families with CHM. An early diagnosis might be crucial for genetic counseling of this type of progressive and still untreatable disease.

Introduction

Choroideremia (CHM; MIM# 303100) is a rare X-linked recessive disease characterized by progressive loss of vision due to the degeneration of choroids, retinal pigment epithelium, and photoreceptors of the retina [1]. Male patients usually develop night blindness in childhood, followed by progressive loss of peripheral vision in the second and third decades of life and potentially culminating in blindness. Central visual acuity is unaffected until the final stage of the disease, when concentric widespread chorioretinal atrophy develops. Female carriers are usually asymptomatic, but at fundus examination, patchy areas of chorioretinal degeneration, due to random X-inactivation (lyonization), can be observed [2]. CHM has an estimated prevalence of 1 in 100,000 and occurs in about 4% of the blind population, and is the second leading cause of hereditary and progressive night blindness after retinitis pigmentosa [3,4].

The disease is caused by mutations in the CHM gene, mapped at chromosome Xq21.2, which is expressed in many tissues, including the retina, choroid, retinal pigment epithelium, and lymphocytes [5]. The CHM gene consists of 15 exons spanning approximately 150 Kb of genomic DNA and encodes an intracellular protein of 653 amino acids, called Rab escort protein-1 (REP-1) [6]. Rab proteins are low-weight guanosine triphosphatase molecules that regulate intracellular vesicular transport. REP-1 is the A component of Rab geranylgeranyltransferase (GGTase) and is involved in the post-translational lipid modification of many intracellular proteins, playing an important role in the process of trafficking between various vesicular compartments of the cell [7,8].

To date, the majority of the mutations found in the CHM gene result in either the truncation of REP-1 product or its complete absence and include large deletions, translocations, and various small mutations (nonsense, frameshift, and splicing mutations) [3,9-15]. Affected men show similar clinical phenotypes in all patients independent of the mutation. The carriers reveal variable severity of the disease depending on the lyonization in the retinal cells, which determines the amount of protein produced. The absence of functional protein, independent of the causative mutation, opens up the possibility of performing the clinical diagnosis of CHM with semiquantitative western blotting of REP-1, followed by DNA and RNA analysis of the CHM gene. In this report, we describe a new in-frame mutation in a splicing site of the CHM gene, identified in an Italian patient with CHM and his family members and the related ocular findings. The study also aims to evaluate the possibility of using western blot analysis to confirm the clinical diagnosis of CHM.

Methods

Subjects

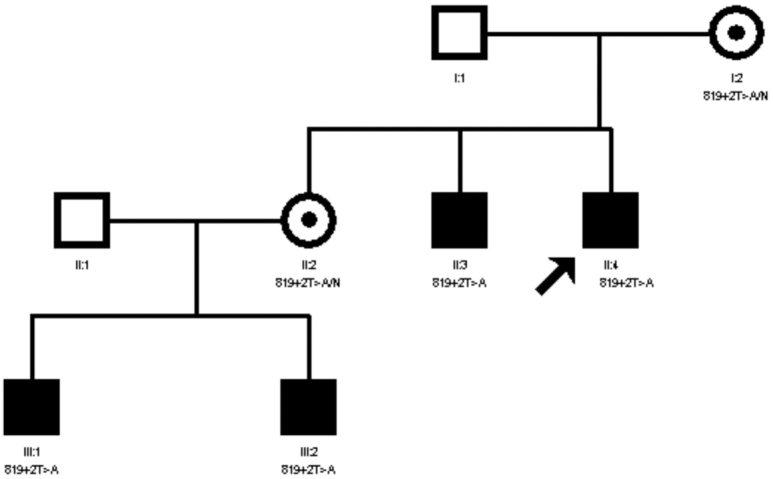

One proband and five family members: three affected male (age 7-43) and two female carriers (age 44-75), all in good general health except for ocular findings in affected males, were recruited from NESMOS Department-Ophthalmology, School of Medicine and Psychology, University “La Sapienza”, Rome, Italy (Figure 1). All the family members were contacted, and after informed consent, according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, was received, a complete ophthalmological examination and a genetic analysis were performed in all six individuals.

Figure 1.

Pedigree of an Italian family with choroideremia. Squares and circles indicate males and females, respectively, and the darkened symbols represent the affected members. The patient above the arrow is the proband. Under the symbol (square or circle) of each subject are two rows of information: individual identifier (I:1, I:2, etc.) and genotype for the CHM mutation.

Ophthalmological studies

Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), slit-lamp biomicroscopy, and fundus examination were performed in all family members. Fundus photographs were acquired with Canon retinography (Canon CR-DRi non-mydriatic retinal camera, Tokyo, Japan). Macular optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans were evaluated with Stratus OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditech, Dublin, CA). Visual fields were examined with the Humphrey Field Analyzer HFA II 750 (Carl Zeiss Meditech) with the 30–2 SITA standard program. Full-field electroretinography (ERG) was performed using the Lace System (EREV 2000), according to the standards of the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV). Fluorescein angiography was performed with Heidelberg retinal angiography (HRA, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany).

Determination of Rab escort protein-1 levels

The levels of expression of the REP-1 protein were determined with western blot analysis using specific mouse monoclonal REP-1 antibody, clone 2F1 (SC-23905, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Dallas, TX) against the 415 C-terminal amino acids of REP-1 [16,17] and anti-beta actin (A2066; Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) for normalization. Protein lysates were obtained from Epstein Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) of the proband, his family members, and controls. LCLs were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL, Grand Island NY), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml HEPES buffer Fluka Holdings AG, Buchs, Switzerland), and 100 U/ml streptomycin and maintained in a 37 °C incubator (Forma Scientific LABEQUIP LTD, Markham, Ontario, Canada) in 5% CO2 atmosphere and 100% nominal humidity. The cells were washed with DPBS (14190-094, Dulbecco’s phosphate buffer saline without CaCl2, and MgCl2; GIBCO by life technologies, Grand Island, NY ) buffer plus 0.1 mM Na3VO4, and the cell pellets were lysed in Laemmli buffer (0.125 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) containing protease inhibitors. Lysates were boiled for 2 min, sonicated, and quantitated with the Bradford assay. From each sample 50 μg of total protein plus 5% β-mercaptoethanol were size-fractionated using the NuPage Novex system from Invitrogen (Carlsband, CA). After incubation with a peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody, the immunoreactive bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) on autoradiographic film.

Mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes or LCLs using standard organic extraction procedures. Briefly: the DNA samples were purified with phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and precipitated with ethanol using UltraPure™ Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1, v/v; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. DNA samples were stored below -20°C until use. To screen the CHM gene for mutations, all the exons and splice junctions were amplified using the primers designed by Yip et al. [14].

PCR reactions for direct sequencing of 50 ng of genomic DNA were performed in 50 µl volumes containing 200 μM of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP), 0.3 mM of each primer, and 1.25 units of AmpliTaq Gold® DNA Polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY) in PCR buffer. Amplification of cDNA for sequencing was done as described for genomic DNA, except that 1 ng of each primer was used. QIAquick spin columns (Qiagen, Mississauga, Canada) were used to purify the PCR products to be sequenced. Purified PCR products were sequenced in forward and reverse directions using the BigDye Terminator chemistry and an ABI Prism 3100 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Messenger RNA (mRNA) was extracted from LCLs using the Oligotex Kit (Qiagen), in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol, and was reverse transcribed to cDNA using an oligo-p(dT) primer and Accuscript RT transcriptase (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA). Synthesis of the second strand was performed with specific primers [9]: 2 µl of the proband’s and the female carrier’s cDNA were used as template in a total volume of 50 µl containing 20 pmol each primer (forward and reverse), 10X Taq DNA polymerase buffer (500 mM Tris/HCl, 100 mM KCl, 50 mM [NH4]2SO4, 20 mM MgCl2), 200 µM each deoxynucleotide, and 2 U Taq DNA polymerase. PCR products were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, excised, and sequenced.

Results

Clinical phenotype

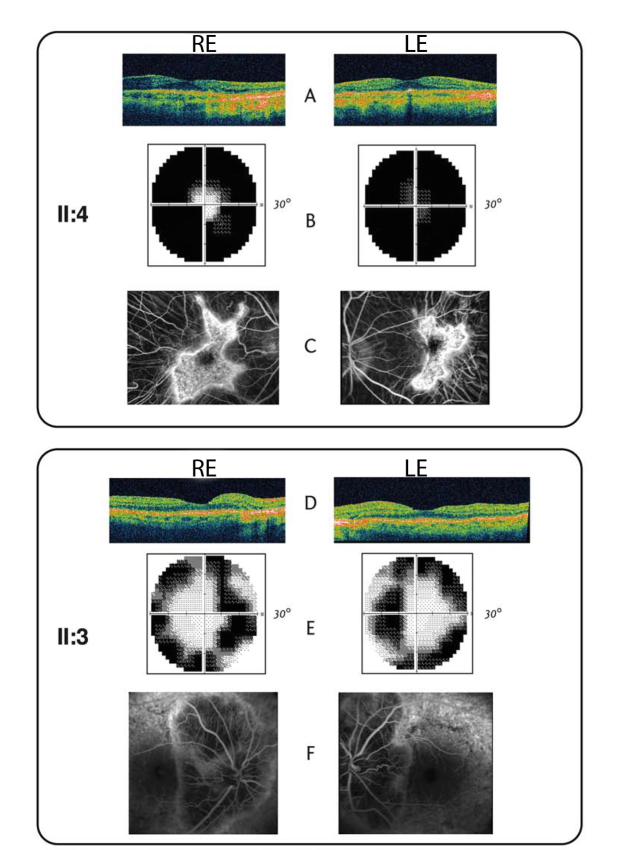

Patient II:4

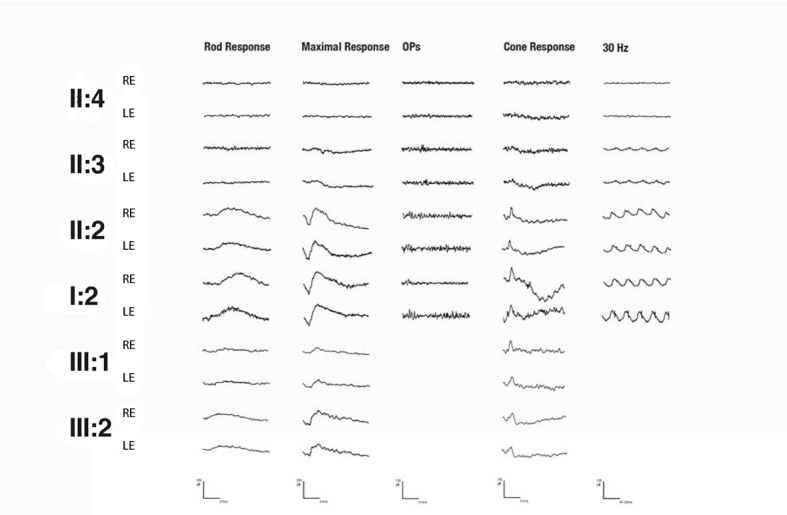

The proband, a 40-year-old Italian man, was the third child of non-consanguineous healthy parents (Figure 1). He complained of night blindness. A previous diagnosis of degenerative retinopathy was reported at the age of 18 years. Best-corrected visual acuity was 1.0 in both eyes. The anterior segment was within normal limits, and intraocular pressure was 15 mmHg in both eyes. The fundus showed widespread confluent areas of nummular retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choriocapillaris atrophy, sparing only the centermost macular region. OCT through the macular region revealed a demarcation line between the island of the remaining retina within the macula and the surrounding area of chorioretinal atrophy, and an intense back-scattering in the OCT image, which corresponds to chorioretinal atrophy (Figure 2A). In both eyes, a deep scotoma with a residual less than 10° central visual field was found (Figure 2B). Fluorescein angiography showed a perifoveal star-shaped hyper-fluorescence area; choroidal vessels were visible in the large confluent areas of atrophy (Figure 2C). Full-field ERG was undetectable in all responses (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Optical coherence tomography, visual field, and fluorescein angiography of the proband and his brother. Widespread chorioretinal atrophy with relative sparing of the macular region and visual field constriction are found. Note the greater severity of the anatomic and functional findings of the proband II:4 (A, B, C) compared to his older brother II:3 (D, E, F). RE,right eye; LE, left eye.

Figure 3.

Comparison of electroretinography findings of family members. Note the undetectable full-field electroretinography of all responses in the proband (II:4). The dark adapted responses were unrecordable in II:3 and markedly impaired in III:1 and III:2, while the light adapted responses were less compromised. Electrofunctional responses in female carriers (II:2 and I:2) were slightly impaired. RE, right eye; LE, left eye.

Patient II:3

The elder proband’s brother was 43 years old with no significant medical history (Figure 1). No prior ocular findings were reported. At examination, BCVA was 1.0 in both eyes; intraocular pressure and anterior segment were within normal limits. Fundus examination revealed similar findings as reported in the proband, with large confluent patches of RPE and choroid atrophy in the mid-periphery and in the paramacular area. OCT showed normal thickness of the fovea, minimal thinning of the outer retina, and moderate chorioretinal atrophy (Figure 2D). Visual field examination showed an annular scotoma in both eyes (Figure 2E). Fluorescein angiography showed hyper-fluorescence areas in the mid-periphery and in the paramacular region, due to diffuse RPE atrophy (Figure 2F). Full-field ERG was undetectable in rod responses and in oscillatory potentials (OPs), and extremely reduced in the maximal response. Cone response and 30 Hz flicker responses were markedly decreased (Figure 3).

Patient II:2

The proband’s sister, 44 years old, had no significant medical history. At examination, BCVA was 1.0 in both eyes; intraocular pressure and anterior segment were within normal limits. Fundus examination revealed in both eyes normal posterior poles and patchy areas of chorioretinal pigmentation in the extreme periphery. Visual field was within normal limits in both eyes. Full-field ERG demonstrated moderate reduction of scotopic response, and the maximal response and OPs slightly decreased in cone response and 30 Hz responses (Figure 3).

Patient I:2

The proband’s mother was a 75-year-old Italian woman with no medical history of ophthalmologic pathology. At examination, BCVA was 0.8 in the right eye and 0.7 in the left eye; intraocular pressure was 17 mmHg in both eyes. Senile cataract was present in both eyes (left eye > right eye). Nonspecific RPE and choroid mottling were detectable in the extreme periphery at fundus examination. Full-field ERG showed a slight decrease in scotopic response, maximal response, OPs, and 30 Hz flicker responses, while cone response was within normal range (Figure 3).

Patient III:1

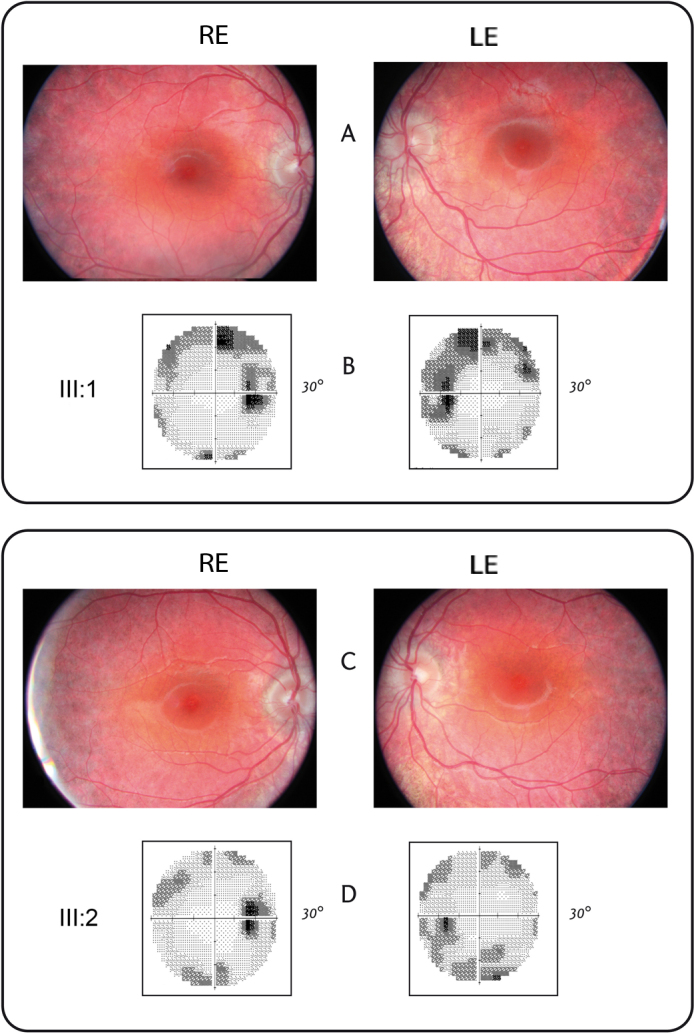

The first child of II:2 was a 9-year-old boy (Figure 1). His medical history was not significant. At examination, BCVA was 1.0, and anterior segment was normal in both eyes. Fundus examination showed in both eyes normal optic discs, normal macula, and pigment dystrophy in the retinal periphery (Figure 4A). Perimetry showed a concentric constriction of the visual field (Figure 4B). Full-field ERG were barely detectable in the rod response, extremely reduced in the maximal response, while the cone response was slightly decreased (Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Fundus photography and perimetry of the two children. Retinal pigment epithelium mid-periphery pigment changes are already visible. Perimetry shows concentric reduction in the visual field in patient III:1 (A, B) and patient III:2 (C, D). RE, right eye; LE, left eye.

Patient III:2

The second child of II:2 was a 7-year-old boy (Figure 1). At examination, BCVA was 1.0, and anterior segment was normal in both eyes. The fundus examination was similar to III:1. The perimetry showed a minor concentric reduction in the visual field, and full-field ERG was less compromised compared to those of his brother (Figure 3 and Figure 4C,D).

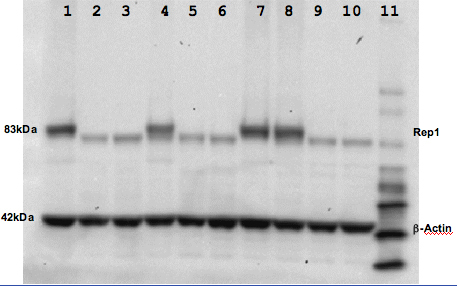

Rab escort protein-1 levels

Semiquantitative analysis of the REP-1 protein was performed by western blot analysis of REP-1 levels in cellular lysates from LCLs of patients with CHM and one female carrier (II:2). A band of 83 kDa corresponding to the expected size of the REP-1 protein was detected in normal cells from healthy men and women and the female carrier II:2. LCLs from the CHM proband (II:4) and the other affected men (II:3, III:1, III:2) did not show detectable amounts of normal REP-1 protein but a smaller protein band (also present in the female carrier) and probably corresponding to a shorter translational product of REP-1 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Immunoblot analysis of the Rab escort protein-1 protein from patients II:4 (2, 9), II:3 (3, 10), III:1 e III:2 (5, 6); from the female carrier II:2 (4, 8); from the normal controls: male (1) and female (7); lane 11: ladder in the range of 20–220 kDa (MagicMark XP Western Protein Standard) and female (7, 11).

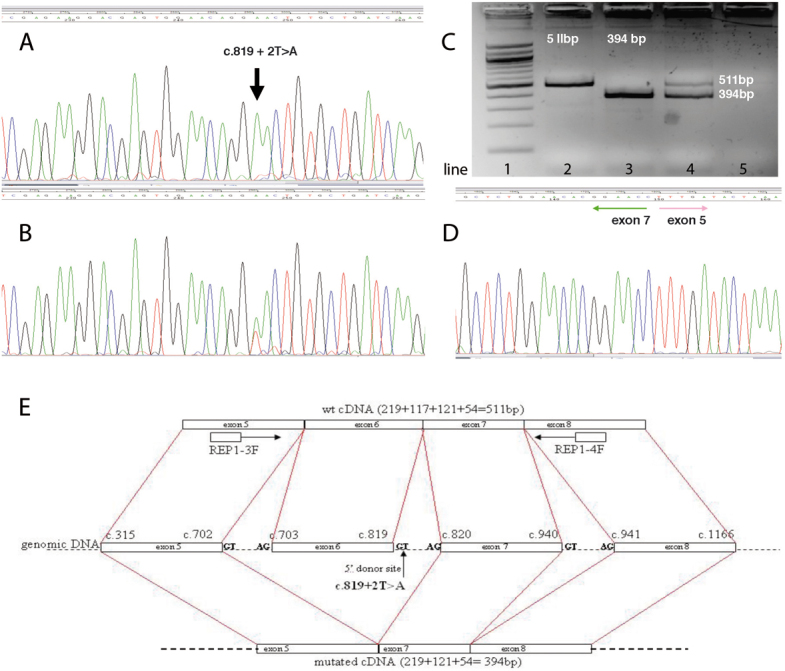

Mutation analysis

A novel mutation, c.819+2T>A, at the donor splicing site of intron 6 of the CHM gene was detected and predicted to result in a transcript deleted of exon 6 (CHM, c.703_819del). The patients with CHM were hemizygous, and the female carriers were heterozygous for this mutation (Figure 1 and Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A novel splice-site mutation of CHM gene. A: Mutation analysis of CHM gene performed by direct sequencing on genomic DNA from patient II:4 showed a new mutation c.819+2T>A. B: The female carrier II:2 resulted heterozygous for the mutation c.819+2T>A. C: Mutation analysis of CHM gene performed by RT-PCR in mRNA from the proband (line 3), female carrier II:2 (line 4), wild type male (line 2), Ladder 100 bp (line 1) and negative reaction control (line 5). D: Sequencing analysis of the 394 bp cDNA reverse transcripted from mRNA patient II:4 show that the whole exon 6 is deleted as result of splicing mutation c.819+2T>A. E: Consequence of CHM gene splicing mutation c.819+2T>A on mRNA.

To confirm the predicted mRNA splicing, the cDNA region encompassing exons 5–8 was specifically amplified in mRNAs from the proband and the female carrier (II:2). The result demonstrated that the change from GT to GA at the consensus donor splicing site of intron 6 affects CHM RNA processing. The CHM c.819+2T>A mutation resulted in an exon skipping, which created an in-frame deletion of exon 6. The sequence analysis of the excised band from patient II:4 revealed only one aberrantly spliced mRNA lacking exon 6 and the absence of a normal transcript, while cDNA from carrier II:2 showed the presence of normal and mutated transcripts (Figure 6). The absence of the 117 bases of exon 6 from CHM mRNA maintains the reading frame, predicting a protein product that lacks amino acids 235–273 (p.L235_Q273del).

Discussion

CHM is a rare genetic disorder caused by truncating mutations in the CHM gene, encoding REP-1. Affected men develop night blindness during the second decade of life, followed by visual field constriction and severe visual impairment by the fourth decade of life. Women are usually asymptomatic or suffer symptoms such as those reported in the early stages of CHM in the affected men. In rare cases, due to unfavorable lyonization, female carriers even suffer the full effects of CHM [18]. We report six members of an Italian family with CHM who presented variable rates of visual change and degrees of functional involvement.

The adult affected men, patients II:4 and II:3, exhibited the classic advanced chorioretinal degeneration at the ocular fundus examination. OCT data showed extrafoveal RPE changes and a normal overlying neural retina in accordance with early RPE involvement. The profound paracentral scotomas observed in two patients could correlate to the concentric progressive constriction of the visual field in the CHM, affecting first the mid-peripheral retina and then the posterior pole.

The proband presented profound symmetric chorioretinal atrophy with preservation of the central macula. Symptoms and anatomic and functional abnormalities were more severe than in his elder brother. The clinical manifestation of CHM showed considerable intrafamilial as well as interfamilial variable expressivity. In the proband, all the electrofunctional responses were absent, while his brother presented undetectable rod response and marked impairment in light adapted function, assuming progression of rods before cone degeneration.

Women usually do not express changes in visual acuity, the peripheral field, or ERG responses. Cases I:2 and II:2, mother and daughter of the proband, respectively, were asymptomatic, although they showed similar patchy areas of chorioretinal pigmentation at fundus examination.

The young sons of carrier II:2 showed a clinical phenotype consistent with the early stage of CHM, with RPE peripheral pigment changes already present. The deterioration of the visual field and of electrofunctional responses was severe and widely exceeded the funduscopic appearance. The dark adapted function was markedly impaired, while cone response was slightly reduced, implying greater rod than cone vulnerability to compromised REP-1 function in affected males [19].

All mutations identified thus far in affected men, point mutations or large genomic rearrangements, lead to a truncated unstable or absence of the REP-1 protein [14,15,20]. This could explain why individuals with different mutations in the CHM gene share clinical features. Previous reports suggest that immunoblotting of cell lysates might be informative for CHM diagnosis [17] and that this approach should be used as the final step of molecular diagnosis as suggested by Garcia-Hoyos et al. [3]. Analyzing the REP-1 protein levels is a reliable test for confirming the clinical diagnosis of CHM. In fact, the family’s affected men did not show detectable amounts of normal REP-1 protein. In this family, western blot analysis also confirmed the carrier status of the proband’s mother (II:2) showing the presence of two bands: a 83 kDa band corresponding to the normal allele product and a smaller band, also seen in the patients with CHM, corresponding to the shorter translational product resulting from the in-frame mutated allele. Direct sequencing of genomic DNA and mRNA transcript from the patients with CHM and the carrier expands the repertoire of mutations that cause CHM and confirms the western blot results. In this family, the identified mutation c.819+2T>A, which changes the GT consensus dinucleotide at the beginning of intron 6, completely abolishes the splice site and leads to a CHM allele with in-frame exon 6 skipping. The lost residues (codons 235–273) encoded by exon 6 are part of domain II of the REP-1 protein, involved in the interaction with Rab7 [20]. Rab7 is a member of the large subgroup of Rab GTPases, involved in multiple stages of intracellular vesicular transport [8]. The same in-frame deletion of the entire exon 6 from the mature transcript was previously reported in one Caucasian patient with CHM and one Chinese patient with CHM [11,14]. In the first case, the predicted loss of 39 amino acids from the REP-1 mutant protein (p.L235_273Qdel) was caused by the insertion of an L 1 retrotrasposon element in reverse orientation into the coding region of exon 6. In the second case, the same consequence was due to an acceptor site splicing mutation at the junction between intron 5 and exon 6. The 39 missing amino acids are part of the conserved region SCR2 of REP-1, which forms a hydrophobic groove proposed to bind one of the geranyl-geranyl groups attached to the C-terminus of the Rab proteins in the post-translational prenylation of intracellular proteins [11,21]. The presence of the product of the mutant allele of the CHM gene in affected men and female carriers, as shown with western blot analysis (Figure 5), suggests that in this family the disease could be caused by the loss of function of the REP-1 protein rather than by its absence.

We propose that the clinical diagnosis of CHM can be confirmed with a three-step protocol. As the first step, we propose immunoblot analysis in LCLs, followed by direct sequencing of the CHM gene, and finally mRNA study, when necessary. The complete absence of the REP-1 normal protein as a consequence of the mutations identified in the CHM gene suggested we should perform a rapid diagnostic test using semiquantitative western blotting analysis. The immunoblot was informative even when the mutation did not disrupt the reading frame, allowing us to distinguish the normal protein from the variant. The absence of the REP-1 normal protein in the proband is sufficient to confirm the clinical diagnosis of CHM [17], and western blot allows extends the screening to other family members, with the identification of female carriers. Sequence analysis in patients with absent or abnormal protein confirms the result of western blotting and allows us to identify the causative mutation of CHM, offering prenatal diagnosis to female carriers. The last step is optional and depends on the type of mutation identified.

CHM is a rare retinal disease in which identifying female carriers is possible and crucial to prevent this type of progressive and still untreatable disease. Our results emphasize the value of an approach that correlates genetic and ophthalmologic data for defining carrier status as well as confirming the clinical diagnosis in young patients.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no propriety or commercial interests in any of the materials discussed in this article. Funding, support and role of sponsors: The authors did not receive any financial or material support.

References

- 1.Cremers FP, van de Pol DJ, van Kerkhoff LP, Wieringa B, Ropers HH. Cloning of a gene that is rearranged in patients with choroideraemia. Nature. 1990;347:674–7. doi: 10.1038/347674a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohba N, Isashiki Y. Clinical and genetic features of choroideremia. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2000;44:317. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(00)00153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Hoyos M, Lorda-Sanchez I, Gomez-Garre P, Villaverde C, Cantalapiedra D, Bustamante A, Diego-Alvarez D, Vallespin E, Gallego-Merlo J, Trujillo MJ, Ramos C, Ayuso C. New type of mutations in three spanish families with choroideremia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:1315–21. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauthner M. Ein Fall von Choroideremia. Naturwissenschaft. 1872;2:191–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Bokhoven H, van den Hurk JA, Bogerd L, Philippe C, Gilgenkrantz S, de Jong P, Ropers HH, Cremers FP. Cloning and characterization of the human choroideremia gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1041–6. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.7.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seabra MC, Brown MS, Slaughter CA, Sudhof TC, Goldstein JL. Purification of component A of Rab geranylgeranyl transferase: possible identity with the choroideremia gene product. Cell. 1992;70:1049–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira-Leal JB, Hume AN, Seabra MC. Prenylation of Rab GTPases: molecular mechanisms and involvement in genetic disease. FEBS Lett. 2001;498:197–200. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goody RS, Rak A, Alexandrov K. The structural and mechanistic basis for recycling of Rab proteins between membrane compartments. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1657–70. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4486-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Hurk JA, Schwartz M, van Bokhoven H, van de Pol TJ, Bogerd L, Pinckers AJ, Bleeker-Wagemakers EM, Pawlowitzki IH, Ruther K, Ropers HH, Cremers FP. Molecular basis of choroideremia (CHM): mutations involving the Rab escort protein-1 (REP-1) gene. Hum Mutat. 1997;9:110–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)9:2<110::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McTaggart KE, Tran M, Mah DY, Lai SW, Nesslinger NJ, MacDonald IM. Mutational analysis of patients with the diagnosis of choroideremia. Hum Mutat. 2002;20:189–96. doi: 10.1002/humu.10114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Hurk JA, van de Pol DJ, Wissinger B, van Driel MA, Hoefsloot LH, de Wijs IJ, van den Born LI, Heckenlively JR, Brunner HG, Zrenner E, Ropers HH, Cremers FP. Novel types of mutation in the choroideremia (CHM) gene: a full-length L1 insertion and an intronic mutation activating a cryptic exon. Hum Genet. 2003;113:268–75. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDonald IM, Sereda C, McTaggart K, Mah D. Choroideremia gene testing. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2004;4:478–84. doi: 10.1586/14737159.4.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Sumaroka A, Aleman TS, Schwartz SB, Windsor EA, Roman AJ, Stone EM, MacDonald IM. Remodeling of the human retina in choroideremia: rab escort protein 1 (REP-1) mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4113–20. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yip SP, Cheung TS, Chu MY, Cheung SC, Leung KW, Tsang KP, Lam ST, To CH. Novel truncating mutations of the CHM gene in Chinese patients with choroideremia. Mol Vis. 2007;13:2183–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Q, Liu L, Xu F, Li H, Serveev Y, Dong F, Jiang R, MacDonald I, Sui R.Genetic and phenotypic characteristics of three Mainland Chinese families with choroideremia. Mol Vis 201218309–16.Epub 2012 Feb 3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexandrov K, Horiuchi H, Steele-Mortimer O, Seabra MC, Zerial M. Rab escort protein-1 is a multifunctional protein that accompanies newly prenylated rab proteins to their target membranes. EMBO J. 1994;13:5262–73. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald IM, Mah DY, Ho YK, Lewis RA, Seabra MC. A practical diagnostic test for choroideremia. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1637–40. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh M, McCulloch C, Parker JA. Pathological study in a female carrier of choroideremia. Can J Ophthalmol. 1988;23:181–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ponjavic V, Abrahamson M, Andreasson S, Van Bokhoven H, Cremers FP, Ehinger B, Fex G. Phenotype variations within a choroideremia family lacking the entire CHM gene. Ophthalmic Genet. 1995;16:143–50. doi: 10.3109/13816819509057855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sergeev YV, Smaoui N, Sui R, Stiles D, Gordiyenko N, Strunnikova N, Macdonald IM. The functional effect of pathogenic mutations in Rab escort protein 1. Mutat Res. 2009;665:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.02.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pylypenko O, Rax A, Reents R, Niculae A, Sidorovitch V, Cioaca MD, Bessolitsyna E, Thoma NH, Waldmann H, Schlting I, Goody RS, Alexandrov K. Structure of Rab Escort Protein-1 in Complex with Rab Geranylgeranyltransferase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:483–94. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]