Abstract

The recent discovery of 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl (CB11) as a byproduct of pigment manufacturing underscores the urgency to investigate its biological fate. The high level and ubiquity of atmospheric CB11 indicates that inhalation is the major route of exposure. However, few data on its uptake and elimination exist. A time course study was performed exposing male Sprague-Dawley rats to CB11 via nose-only inhalation with necropsy at 0, 4 and 8 h post exposure. An analytical method for CB11 and mono-hydroxylated metabolites employing pressurized liquid extraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry yielded efficient recovery of CB11 (73±9%) and its metabolite 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl-4-ol (4-OH-CB11) (82±12%). Each rat was exposed to 106 μg/m3 vapor-phase CB11 for 2 h and received an estimated dose of 1.8 μg. Rapid apparent first-order elimination of CB11 was found in lung, serum and liver with half-lives of 1.9, 1.8 and 2.1 h, respectively. 4-OH-CB11 was detected in the liver but not the lung or serum of exposed animals and displayed apparent first-order elimination with a 2.4 h half-life. This study demonstrates rapid metabolism of CB11 and elimination of 4-OH-CB11 and suggests that the metabolite is not retained in the body but is susceptible to further biotransformation.

Introduction

Atmospheric polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), a family of semi-volatile chlorinated hydrocarbons with one to ten chlorine substituents, have received growing concern over the past decade for their role in human exposure by the inhalation route. The lack of observable changes in atmospheric concentration (1), decades after the ban of most PCB manufacturing in 1979, indicates that a wide range of PCB emission sources are still present in the environment. In fact, due to the volatility of lower-chlorinated PCBs, the residues in contaminated water, industrial facilities, waste sites, and caulking material in buildings are readily released and become airborne. Atmospheric PCBs are generally found at higher concentrations in regions with higher population, in particular urban areas (2), suggesting a correlation between air contamination and human activities. There is a widely held notion that the production of PCBs was halted in the late 1970s. However, 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl (CB11), one of the most abundant and widely distributed congeners in the Chicago airshed, is still being produced inadvertently during pigment manufacturing (3). CB11 has been postulated as a product of microbial dechlorination of 3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl (CB77) (4), but this minor source is unlikely to account for the high concentrations observed. The high level of environmental CB11 in air was unexpected owing to its absence in the manufactured commercial mixtures that led to widespread contamination. As a consequence, few researchers thought to determine the presence of CB11 until it was detected at notable levels in various environmental matrices and commercial samples including water (1 to > 100 pg/L); suspended particulate matter in water, biota, sediment (<20 ng/g); Antarctic and urban air (up to 70-80 pg/m3); effluents from wastewater treatment plants (up to 490 ng/L from pigment manufacturers) and consumer goods (up to 38 ng/g) (3, 5-9). Although evidence for extensive exposure to CB11 has been mounting, there is a paucity of information on the biologic consequences of exposure.

The importance of lower-chlorinated PCBs has been neglected until relatively recent observations of a decreasing trend of dietary PCB levels and increasing proportion of lower-chlorinated PCBs (10). Lower-chlorinated PCBs have little tendency to bioaccumulate and are less likely to be taken up through diet due to their lower lipophilicity and lower persistency (11). The lower chlorination leaves more unsubstituted positions on the aromatic rings, making these congeners susceptible to metabolism initiated by cytochrome P450 (CYP)–mediated oxidation. Depending on the manner of oxidation, the products may be hydroxylated metabolites (OHPCBs), dihydrodiols, or epoxide intermediates that may form methylsulfonyl metabolites following the mercapturic acid pathway of glutathione-conjugated PCBs (12). Some hydroxylated higher-chlorinated PCBs were found to be strongly retained in blood due to their binding to the thyroxin transporter (13, 14), while many OH-PCBs with lower chlorination are shown to be more readily biotransformed by conjugation than those with higher chlorination (15). Nevertheless, the toxicokinetics of most lower-chlorinated PCBs remains unexplored. In particular, little information has been reported for CB11 except that it is metabolized rapidly by hepatic CYP1A to 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl-4-ol (4-OH-CB11) as the major hydroxylated metabolite (16, 17).

Similar to other semi-volatile lower-chlorinated PCBs investigated in our earlier studies (17, 18), inhalation exposure is the major route of exposure to CB11. Airborne PCBs are rapidly taken up and distributed to body tissues via inhalation exposure. PCBs found in technical Aroclor mixtures are eliminated within hours after exposure from different tissues, with biological half-lives increasing in the order of rat liver, lung, brain and serum (18). Their rates of elimination differ by target organ as well as by the substitution pattern of congeners (18). Selective uptake and elimination thus result in distinct congener spectra in body tissues following subacute and subchronic inhalation exposure of mixtures of airborne congeners generated from Aroclors (17, 18). In order to understand toxicokinetics of the non-Aroclor CB11, we performed an acute inhalation exposure to CB11 vapor and investigated the time course of uptake and elimination in rat lung, serum and liver. In addition, we identified for the first time the formation of a CB11 metabolite in vivo. Although inhalation studies have been performed with airborne PCB congeners previously, this study is the first to report the level and elimination rate of a hydroxylated metabolite of an inhaled PCB congener.

Experimental Section

Chemicals

Congeners are designated by their IUPAC identities, numbered CB1 (monochlorobiphenyl) through CB209 (decachlorobiphenyl) (19). CB11, 4-OH-CB11, 3,3′-dichloro-2-methoxy-biphenyl (2-MeO-CB11), 3,3′-dichloro-5-methoxy-biphenyl (5-MeO-CB11), 3,3′-dichloro-6-methoxy-biphenyl (6-MeO-CB11), 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl (CB15), 3,4-dichlorobiphenyl-4′-ol (4′-OH-CB12), 2,4′-dichlorobiphenyl-4-ol (4-OH-CB8) were synthesized in our laboratory (20, 21). 3,5-Dichlorobiphenyl (CB14) was purchased from AccuStandard (New Haven, CT). Florisil (60-100 mesh), tetrabutylammonium sulfite, absolute ethanol, potassium hydroxide and pesticide grade solvents were supplied by Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Diazomethane was synthesized from N-methyl-N-nitroso-p-toluenesulfonamide (Diazald) as described previously (22).

Generation and characterization of CB11 exposure

Pure CB11 vapor was generated into our exposure system as previously described for PCB mixtures (23). Briefly, clean dry air (4.0 L/min) was bubbled through neat CB11 in an impinger held at 25.0°C in a precision water bath (Thermo Scientific, Portsmouth, NH). The CB11 vaporladen air was then diluted with clean, dry air (6.0L/min) and supplied to a radial nose-only exposure system (InTox, Inc., Albuquerque, NM) at 10.0 L/min and collected at the exposure system outflow using an XAD cartridge sampling over the entire course of exposure. The vapor generation and exposure systems were held within a 6 m3 secondary containment structure operated at negative pressure to the room. A sham exposure nose-only system for control animals was located in an adjacent lab where no PCBs have ever been deliberately introduced.

Air-sampling cartridges were loaded with 10 g of pre-extracted Amberlite XAD-2 polymeric absorbent resin (Supelco Analytical, Bellefonte, PA) packed with filters and cleaned glass wool. After collection of CB11 vapor, the cartridges were placed in sealed Ziploc® bags, stored at 4°C until analysis and were later extracted using the same PLE (pressurized liquid extraction) protocol as described below. The XAD extracts from CB11 exposure, sham exposure, field blank and method blank were spiked with 100 ng CB15 as internal standard prior to analysis by GCECD.

Animal treatment

Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Iowa. Animals were housed in our on-site vivarium with food and water provided ad libitum. Liver tissues from donor C57/Bl6 mice were used for analytical methods development. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) (237.6 ± 1.6 g) were exposed in the nose-only system to either the CB11 vapor (n=4 rats/group × 3 groups), or HEPA and activated charcoal-filtered laboratory air (n=4) for 1 h, then allowed for 1 h break and later exposed for another 1 h. Thus the exposure duration was 2 h yet the total time from the start to the end of exposure was 3 h. Use of the nose-only system ensured minimal dermal or oral exposure arising from deposition of PCBs onto fur and subsequent grooming. Sentinel rats from the same shipment (n=2) were maintained in our vivarium during the period of study for health surveillance. Groups of PCB-exposed animals were euthanized serially at 0 h, 4 h and 8 h post exposure by overdose with isoflurane followed by cervical dislocation. Sham-exposed animals were euthanized at 2 h and 6 h post exposure. Whole blood was collected via cardiac puncture for serum preparation, while livers and lungs were excised and stored at -80°C pending analysis.

Detection method for PCB 11 and OH-PCB11s

PLE (ASE200, Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) was used for the extraction. Pre-extracted PLE cells containing 10 g Florisil and 2 g diatomaceous earth were spiked with a mixture of test standards including 10-200 ng of CB11, 4-OH-CB11, 2-MeO-CB11, 5-MeO-CB11, 6-MeO-CB11 and surrogate standards (CB14 and 4′-OH-CB12). In order to obtain a tissue matrix, approximately 0.5 g livers from non-PCB exposed C57/Bl6 mice were thoroughly homogenized into diatomaceous earth. The cells were then extracted based on the optimized condition as described by Kania-Korwel et al. (22): hexane-dichloromethane-methanol (50:45:10, v/v), 100°C, 10.3 MPa (1500 psi) with a 6-min heating time, 1 static cycle of 5 min and a 35% cell volume flush. The extract was concentrated to 0.75 mL in an evaporator (TurboVap II, Caliper Life Sciences Inc., Hopkinton, MA). Temperature (43°C) and flow pressure (34.5 kPa, 5 psi) were optimized for high recovery and efficient concentration.

The concentrated extract went through derivatization with 0.5 mL diazomethane in diethyl ether to transform OH-PCBs to their methoxylated derivatives (MeO-PCBs) for gas chromatography (GC) analysis. The extract containing PCBs and MeO-PCBs were further purified after eliminating diazomethane residue under a gentle stream of nitrogen. Several cleanup approaches were employed and compared systematically as described in Results and Discussion. Sulfur, a common impurity that interferes with electron capture detector, was removed by tetrabutylammonium sulfite (TBA-s) treatment, followed by concentrated sulfuric acid treatment as previously described (18): 2-Propanol and TBA-s (2 mL) were mixed with 1 mL sample and separated from the hydrophobic phase with the addition of 5 mL ultra-pure water; the hydrophobic layer was then treated with concentrated sulfuric acid for overnight. For base treatment, we added 2 mL of 96% ethanol and 0.4 g potassium hydroxide to the derivatized and reconstituted sample solution (1 mL). After shaking for 1 h at 50°C, the hydrophobic layer separated with the addition of 7 mL ultra-pure water and was transferred for subsequent column elution. To prepare an acidified Florisil column, 0.8 g deactivated (combusted at 450°C overnight) Florisil and 0.4 g acidified Florisil (Florisil: concentrated sulfuric acid, 2:1, wt/wt) was packed tightly into a 23 cm disposable glass pipette with the latter on the top. Columns were stored in an oven at 130°C until elution. An approximate 1 mL sample was eluted from the column using 10 mL hexane/dichloromethane (50:50, v/v). The solvent of the eluate was then exchanged to 1 mL hexane by repeated evaporation under nitrogen.

For the purified samples, the solvent was exchanged to 1 mL hexane before adding CB15 as internal standard (10-100 ng). The samples containing low levels of analytes – those spiked with less than 50 ng standards – were concentrated to 100 μL under nitrogen. The quantification of PCBs and MeO-PCBs (derivatized OH-PCBs) in the methods development phase of our study was performed by GC equipped with a 63Ni μ-ECD (electron capture detector). A capillary GC column (DB1-MS, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) (60 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm film thickness) was used under the following temperature program: hold at 100°C for 1 min, 10°C/min to 280°C, then hold at 280°C for 5 min. Detector and injector temperatures were 300°C and 250°C, respectively and the flow rate of the carrier gas helium was 1 mL/min.

Quantification of CB11 and 4-OH-CB11 in rat tissue

CB11 and mono-hydroxylated metabolites (OH-CB11s) were extracted from lung, liver and serum by PLE. Each set of tissue samples was accompanied by a method blank, a tissue blank and an ongoing precision and recovery (OPR) sample that was spiked with 20 ng CB11 and 4-OH-CB11. Each sample was spiked with a surrogate standard including 20 ng CB14 and 4-OH-CB8. After pre-extraction of PLE cells containing Florisil and diatomaceous earth, about 1 g of liver, lung, or serum were thoroughly homogenized into diatomaceous earth and divided into two halves for PCB analysis (Fraction A) and for lipid extraction (Fraction B). Fraction A was placed on top of Florisil in PLE cells which were then extracted under the conditions as described above. The concentrated extracts were then purified as described in Results and Discussion. GC-MS was used to quantify the extracted analytes. Sample volumes of 2 μL were injected splitless by an Agilent GC Autosampler into our Agilent 7890A GC system, coupled with an Agilent 5975C inert Mass Selective Detector operated in electron ionization (EI) mode. The separation was carried out on the same column under the same chromatographic conditions as described above for GC-ECD. The mass spectra were acquired using selected ion monitoring (SIM) at m/z of 222.0 and 251.9. CB11 and OH-CB11s concentration were corrected for method blank values and surrogate recoveries. Fraction B was extracted using chloroform-methanol (2:1 v/v) under the same condition using PLE as for Fraction A. The total lipid content was determined gravimetrically after evaporation of solvents to dryness (24). Serum lipids were calculated from total cholesterol and triglycerides (25) that were determined using a commercial test kit (Trig/GB and Chol tests for Roche/Hitachi 917 system; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).

Statistical analysis

Group-level data were compared via t-tests for equal and unequal variance. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data from all PCB-exposed rats were fit using Gauss-Newton non-linear regression to obtain model parameters (SAS v. 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), while the mean from each group was fit with two-parameter exponential decay (SigmaPlot v. 11.0, Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). Summary data are expressed as mean ± standard error, unless stated otherwise.

Results and Discussion

Concentrations of CB11 and its hydroxylated metabolites in tissues

Chromatographic separation and quantification of PCBs and MeO-PCBs were achieved on GC-ECD and GC-MS (both full scan and SIM mode). CB15 was used as the internal standard because the commonly employed internal standard CB30 (26) was found to co-elute with CB11. Surrogate standards included CB14 and 4-OH-CB8 (or 4′-OH-CB12) for quality control and assurance of CB11 and OH-CB11s, respectively. 4-OH-CB8 was used in place of 4′-OH-CB12 during method final development because the GC separation of 4-OH-CB8 from 4-OH-CB11 was consistently better. Linearity of response and low instrumental detection limits were achieved for both CB11 and 4-MeO-CB11 on GC-MS, as determined from their respective calibration curves (linearity r2 > 0.990, Table 1).

Table 1.

Calibration and instrumental detection limit (IDL) of analytes on GC-MS and quality control measures for tissue extraction. Recoveries are expressed as mean percent ± standard deviation.

| CB11 | 4-MeO-CB11 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Calibration on GC-MS |

IDLa 41 pg/mL |

Linearity (r2) 0.991 |

Linear range 1-2000 ng/mL |

IDLa 19 pg/mL |

Linearity (r2) 0.994 |

Linear range 1-2000 ng/mL |

|

| Quality Control for Tissue Extraction | Recovery of OPR n=1-2 |

Lung 85%, 72% |

Serum 72% |

Liver 60%, 75% |

Lung 68%, 77% |

Serum 77% |

Liver 98%, 90% |

|

| |||||||

| Recovery of Surrogateb n=18-22 | 100±20% | 69±6% | 72±12% | 76±23% | 62±10% | 83±12% | |

|

| |||||||

| MDLc | 0.60 ng | 0.71 ng | |||||

|

|

|||||||

| LOQd | 0.90 ng | 1.16 ng | |||||

Determined as the mass corresponding to the sum of mean and three times the SD of seven blank replicates (46).

Respective recovery for CB14 and 4-OH-CB8.

Method detection limit (MDL) determined from blank samples (n=4) analyzed in parallel to all tissues and serum samples according to EPA formula – MDL = tn−1 × SD + x̄)

Limit of quantification (LOQ) determined from minimal level of detection according to EPA formula – MDL = 10 × SD + x̄)

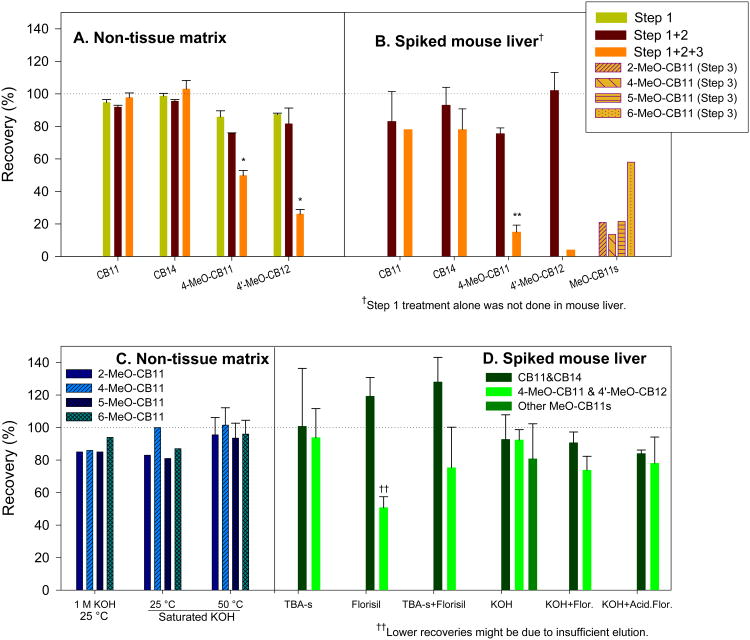

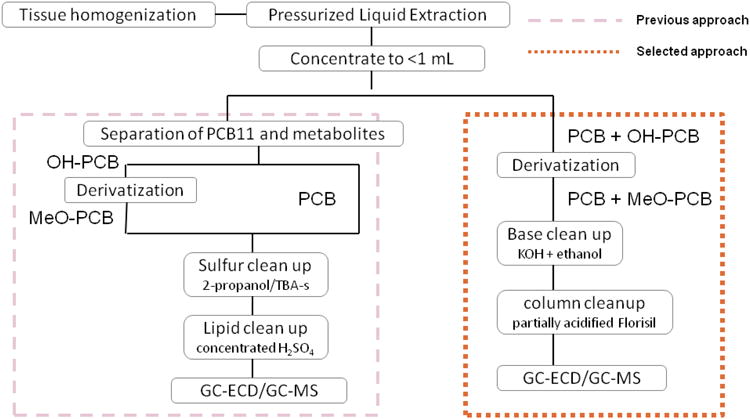

We investigated the methodology for measurement of CB11 and OH-CB11s by spiking clean PLE cells and non-exposed mouse liver with authentic standards. The previously reported procedure (22) (see Figure 1, left side) was employed with adaptations (27) to allow extraction and purification of CB11 and OH-CB11s together. The detected levels of MeO-PCBs (derivatized OH-PCBs) were much lower than the spiked amount, while the recovery of CB11 remained acceptable. We therefore carried out a stepwise examination on the major processes of the procedure. PLE extraction and subsequent derivatization resulted in recoveries over 85%. Sulfur impurity removal by tetrabutylammonium sulfite (TBA-s) and 2-propanol introduced minor reduction of the recoveries that remained above 75%. However, the recoveries of the methoxylated compounds dropped below 50% after treatment with sulfuric acid, while the recoveries of PCBs remained satisfactory (Figure 2A). A parallel stepwise extraction and cleanup of spiked mouse liver exhibited a similar pattern, only with more dramatic loss of MeO-PCBs (Figure 2B). Concentrated sulfuric acid also reduced 42-86% of the levels of all four mono-methoxylated CB11, further suggesting that it is the lower-chlorinated MeO-PCBs that are unstable in sulfuric acid (Figure 2B). Although concentrated sulfuric acid has been applied widely in the clean-up of complex matrices and excels for its capacity to remove fatty acids and organic macromolecules (28), our experiment clearly showed that it was not suitable for quantification of lower-chlorinated OH-PCBs in rat tissue matrix and a less destructive yet effective cleanup technique was needed.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of different approaches for extraction and purification of PCBs and OH-PCBs using pressurized liquid extraction (PLE).

Figure 2.

The recovery rates of analytes and surrogate standards during a three-step extraction and purification treatment (A – non-tissue matrix, B – spiked mouse liver), and under treatment of KOH, tetrabutylammonium sulfite (TBA-s), Florisil or their combinations (C – non-tissue matrix, D – spiked mouse liver). Values are expressed in as mean ± standard deviation. Step 1: pressurized liquid extraction (PLE), concentration and derivatization; step 2: sulfur clean-up; step 3: concentrated sulfuric acid clean-up. Asterisks indicate a significant recovery decrease from the previous step, * = p < 0.05; ** = p< 0.01

Treatment of tissue samples with strong base (e.g. potassium hydroxide, KOH) has been shown effective in eliminating the lipids (28) and elemental sulfur (29), and in degradation of organochlorine pesticides (30). We first confirmed that all four MeO-CB11s were stable in heated saturated KOH solution (Figure 2C). An array of cleanup techniques was then investigated to compare their efficiency in removing impurities (Figure 2D). The treatment with TBA-s alone, Florisil column alone or a combination of the two resulted in generally acceptable recoveries yet with baseline fluctuations and the presence of a significant amount of interference in GC-ECD chromatograms (Figure S1A, S1B and S1C of Supporting Information). Treatment with KOH alone as a substitute for TBA-s and sulfuric acid yielded a cleaner baseline (Figure S1D of Supporting Information) with more reproducible results, and recoveries ranging from 81 to 93% (Figure 2D). The subsequent elution through a deactivated or a partially-acidified Florisil column diminished the recovery of 4-MeO-CB11 and 4′-MeO-CB12 only slightly and was judged acceptable. The Florisil column following KOH treatment successfully removed the colorant from some heavily colored samples, and was able to reduce the interference even more than the KOH treatment alone (Figure S1D and S1E of Supporting Information). The difference between a fully deactivated column and one that was partially-acidified was subtle, while the eluting solvent had a greater impact on reducing interferences. The partially-acidified Florisil column seemed to retain the impurities better than a deactivated one, and allowed a larger volume of eluting solvent. Based on our work, the cleanup and purification procedure was established and incorporated into the extraction and detection method (Figure 1, right side).

In addition to CB11 and CB12, the methoxylated derivatives of several lower-chlorinated PCBs have been shown to be destroyed by concentrated sulfuric acid after derivatization, thus hindering the analysis by GC (31, 32) . In this study, we provided a fast and efficient approach that may also be effective for the analysis of other mono- to trichlorinated OH-PCBs in biological samples. As shown in Figure 1, this approach has fewer purification steps which minimized overall loss of analytes and improved recoveries (Table 1), compared to previously reported recoveries for hydroxylated tri- and tetrachlorobiphenyls: 30-58% for 4,5,3′,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl-3-ol and 4,5,3′,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl-2-ol (22); 52±27% for 2,4,5-trichlorobiphenyl-4′-ol and 48±19% for 2,3,4,5-tetrachlorobiphenyl-4′-ol (33); and 49-95% for 2′,3,5′-trichlorobiphenyl-4-ol (34).

Dose of Inhalation Exposure in Animal Study

We performed an acute nose-only inhalation study to CB11 vapor and collected rat tissues over time after exposure, seeking to investigate the elimination and potential metabolism of inhaled CB11. The exposure was designed at a low-level dosage compared to other in vivo PCB exposure studies in an attempt to approach environmentally representative levels. The quantification of airborne CB11 collected by XAD cartridge showed that the rats were exposed to 106 μg/m3. Under the assumption of 95 breaths/min and a volume of 1.5 mL/breath with complete uptake of inhaled PCB, each rat received 1.8 μg CB11 dose in the entire 3 h period (2 h exposure + 1 h break). A level of CB11 at 87 pg/m3 in ambient air was reported at an Antarctic site in 2004-2005 (6) and 72 pg/m3 was detected in Chicago (3). An adult human breathing a volume of 8 L/min with CB11 concentration of 72 pg/m3 would receive about 1 ng CB11 per day and 1.8 μg every five years. However, PCB contamination in indoor air is often orders of magnitude higher than outdoor air, where the total PCBs can reach 2-4 μg/m3 (10). Assuming CB11 concentration in indoor air is 1 μg/m3, the exposure dose for the resident is estimated to be 13 μg per day. This level is comparable with our experimental exposure level both in terms of dose (13 μg vs 1.8 μg) and body mass adjusted dosage (0.19 μg/kg body weight vs 7.2 μg/kg body weight). With a wide range of primary sources (e.g., paint and consumer goods (8, 35)) in indoor environments, the concentration of airborne CB11 can be elevated compared to ambient air and higher levels of CB11 exposure are probable.

Time Course of CB11 Elimination in Rat Tissue

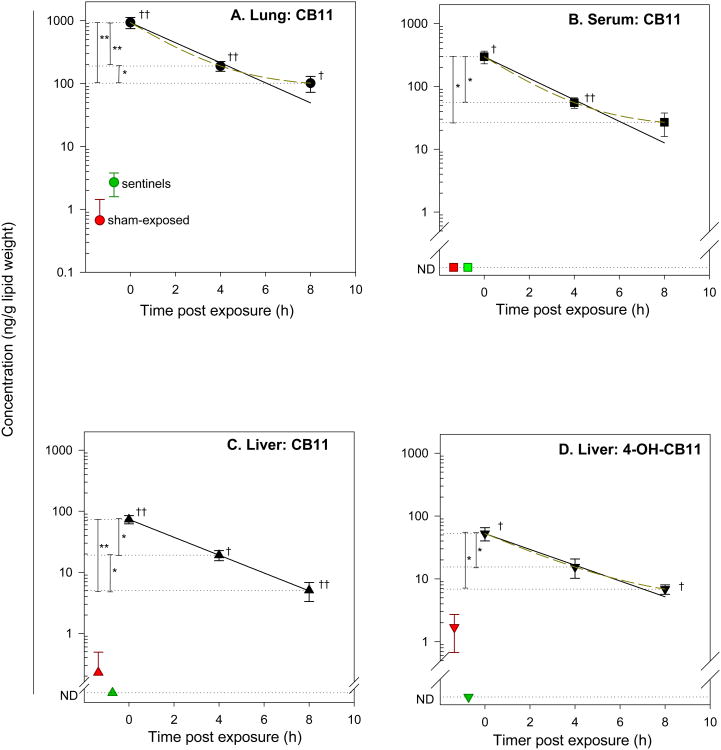

We determined the level of CB11 and its mono-hydroxylated metabolites at three time points post exposure. The method detection limit (MDL) and limit of quantification are reported in Table 1. Tissues in PCB-exposed animals had significantly higher levels of CB11 at all three time points, compared to sham-exposed animals. CB11 was found at the highest concentration in lung, lower in serum and the lowest in liver over the entire 8 h. Marked differences in tissue levels were observed between time points (Figure 3A, 3B and 3C). CB11 concentration in lung, serum and liver decayed quickly after exposure. The blank-subtracted concentrations are reported both on a wet tissue weight basis and a lipid weight basis in Supporting Information (Table S1 and S2). The decline of tissue and serum concentration seemed exponential and fit reasonably well in a one compartmental model. Based on the results of three time points, first-order kinetics was used to determine the biological half-lives as a measure of elimination rate (Figure 3 and Table 2). The rate of elimination in all three tissue types were similar, suggesting that CB11 was distributed rapidly and equilibrium was easily achieved and maintained.

Figure 3.

Time course of concentration change of CB11 in lung (A), serum (B), liver (C) and detected 4-OH-CB11 in liver (D) in rats exposed to CB11 vapor. Values are expressed in ng/g lipid weight, mean ± standard error. The sham-exposed tissue concentrations are shown in red and sentinel in green. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from other time points, * = p < 0.05; ** = p< 0.01; daggers indicate a significant difference compared to sham-exposed group, † = p < 0.05; †† = p < 0.01. Solid line shows the two-parameter exponential decay model fit. ND = not detected.

Table 2.

Single component first order kinetic model and parameter for elimination of CB11 and 4-OH-CB11, generated from nonlinear regression by Gauss-Newton method (SAS v. 9.2) using all tissue samples. t½ is the half life, C0 (ng/g lipid weight: ng/g l.w.) is the initial concentration and r2 is the coefficient of determination for the model fit.

| Model | Lung | CB11 Serum |

Liver | 4-OH-CB11 Liver |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t½ (h) | C0 (ng/g l.w.) | r2 | t½ (h) | C0 (ng/g l.w.) | r2 | t½ (h) | C0 (ng/g l.w.) | r2 | t½ (h) | C0 (ng/g l.w.) | r2 | |

| C = C0e−kt | 1.9 | 932 | 0.913 | 1.8 | 295 | 0.928 | 2.1 | 73.6 | 0.947 | 2.4 | 52.5 | 0.924 |

It is noteworthy that our exposure protocol lasted over a total length of 3 h, with one-hour break in between the two-hour exposure. The fact that the biological half-life of CB11 was shorter than the total length of exposure indicated that significant elimination had occurred before the cessation of exposure. The clearance of CB11 is likely affected by such an exposure regimen in that the post-exposure kinetics may reflect only part of the process. The post-exposure decay of CB11 seemed to follow first-order kinetics, which is consistent with the single-phase decay reported previously for dichlorobiphenyls following oral exposure in rats (36). However, it is possible that the distribution and elimination is more complex, as reported for other PCB congeners. Two-component exponential decay was found for CB136 and CB153 in senescent rat blood, liver and muscle after intravenous administration (37), featuring a initial fast distribution phase (t½ = 1.7-10.6 h) and a subsequent slower elimination phase (t½ =2.3-16.9 days). Similar two-phase elimination was also reported in rats for tetra- and higher chlorinated PCBs following oral exposure, whereas all the dichlorobiphenyls followed single-phase decay (36). Considering the short half-life of CB11, the initial fast distribution phase, if present, would be exceptionally short, possibly several minutes, and thus cannot be accurately assessed in our inhalation exposure study.

The comparison of the toxicokinetics of CB11 with other dichlorobiphenyls after the same duration of inhalation exposure is interesting. 2,4′-Dichlorobiphenyl (CB8) and 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl (CB15) administered as part of Aroclor mixture had much lower pulmonary concentrations than CB11 without reduction in other tissue concentrations (18), suggesting a higher pulmonary retention of CB11. Yet on the other hand, CB11 was eliminated faster than CB8 and CB15, as indicated by their half-lives (2 h vs 5-8 h) (Figure S2 of Supporting Information). This discrepancy can be attributed to several possibilities: 1) CB8 and CB15 were administered as components of a mixture, while CB11 was in neat form. It is possible that other congeners and their metabolites may compete for the tissue binding capacity and the metabolism pathway, leading to altered toxicokinetics (38). 2) Comparing to CB8 and CB15 that have at least one para-substituted chlorine, the unoccupied para- positions of CB11 may lend itself to faster metabolic attack (11), in spite of the retention in lung. 3) The presence of multiple phases in the elimination process may affect the post-exposure kinetics. For example, the most concentrated congeners in Aroclor 1242 vapor, CB1 and CB4 have been eliminated to barely detectable levels during the inhalation exposure, whereas CB28 concentration peaked 1 h after exposure suggesting a redistribution phase (18). Collectively, the relative high concentration of CB11 in lung in the face of a rapid elimination rate after exposure was unexpected and justifies more thorough investigation to address its toxicokinetics and biological fate.

Time course of 4-OH-CB11 Elimination in Liver

The metabolism of CB11 was examined by measuring its mono-hydroxylated metabolites in lung, serum and liver. Although we searched for all four possible derivatives (2-, 4-, 5- and 6-OH-CB11s) using authentic standards, none was detected other than the major hydroxylated metabolite, 4-OH-CB11. The previously reported minor product, 5-OH-CB11, was detected in vitro in a reconstituted CYP metabolism system (17). Considering our exceptionally low dosage, we expected that this metabolite was not detected.

4-OH-CB11 was detected in the liver of all PCB-exposed animals, at levels comparable to its parent compound (Figure 3D). The levels of PCB-exposed groups (0 h and 8 h) were significantly higher than the liver level of sham-exposed rats. The comparison between the 4 h group and the sham group did not reach statistical significance due to larger variance yet the mean was 4-fold and 15-fold higher than that in sham and sentinel rats, respectively. The blank-subtracted concentrations are reported both on a wet tissue weight basis and a lipid weight basis in Supporting Information (Table S1 and S2). The decline over time followed rapid first-order elimination. The half-life was slightly longer than the parent compound (2.4 h vs 2.1 h), leading to an insignificant increase in the ratio of 4-OH-CB11 to CB11: 0.7±0.0 (0 h), to 0.9±0.2 (4 h) and lastly 1.1±0.1 (8 h). 4-OH-CB11 was not detected in any lung or serum samples, indicating that the metabolism of CB11 occurred mainly in liver and the metabolite was readily excreted. The absence of detectable plasma metabolite suggested probable further biotransformation to conjugated phase II metabolites. A recent whole-body distribution study from our lab (data not shown) found that CB11 and OH-CB11s only accounted for a small portion of the radioactivity in liver after administration of [14C]-labeled CB11, suggesting significant quantities of other metabolites. Similarly, the sulfated metabolites of 4-monochlorobiphenyl (CB3) were found at much higher rat serum level than the hydroxylated form (31). Unidentified dihydroxylated metabolite of CB11 was detected at trace amount after incubation with rat liver microsomes or purified CYP enzyme from β-naphthoflavone induced rat liver (16, 17). The formation of hydroxylated CB11 metabolites were affected by an epoxide hydrolase inhibitor, 1,2-epoxy-3,3,3-trichloropropane (17), supporting the presence of intermediate arene oxide – a common phenomenon for lower-chlorinated biphenyls. It would be interesting to verify the formation of dihydroxylated metabolite in vivo and understand the potential connection with 4-OH-CB11 elimination.

Although the retention of OH-PCBs in plasma has been repeatedly studied, thus far none of the lower-chlorinated (mono- to trichlorobiphenyls) OH-PCBs has been reported in vivo. 4-OH-CB14 and 4′-OH-CB 35 exhibited competitive binding to thyroxin transport protein in silico and in vitro (14, 39). Despite high binding affinities to plasma protein, the chances of these compounds accumulating to significant levels are still low if they are readily metabolized and excreted through bile, as in the elimination of CB11. The undetectable levels of mono-hydroxylated CB11 is further confirmed by examination of the detection limits in our study: If 4-OH-CB11 were present at half the method detection limit in serum (Table 1), the concentration in a rat with average serum lipid level would be 0.08 μg/g lipid weight, 25-fold lower than the lowest detected level of OH-PCB reported in humans or wildlife (13). This further strengthens the argument that environmental exposure to CB11 does not result in hydroxylated metabolite retention. This may contribute to lower toxicity of CB11 compared to PCBs that yield accumulation of reactive metabolites.

In spite of being the route of entry, the lung was expected to retain little hydroxylated metabolites, due to the extremely high perfusion rate and the relatively low abundance of CYP enzyme (40, 41). Moreover, in two studies investigating the metabolism of ten dichlorobiphenyls by CYP enzyme, it has been shown that the metabolism of CB11 heavily favors CYP1A relative to CYP2B, both in microsomes and with purified enzyme (16, 17). The distribution profiles of CYP1A/2B in lung and liver apparently facilitate its preferential metabolism in liver, with CYP2B at much higher level than CYP1A in rat lung but lower in rat liver (41, 42). Nevertheless, other CYP isoforms may also contribute to the metabolism of CB11 and their potential effect has not been investigated. The propensity of the lung to retain secondary metabolites of CB11, as was shown with a few PCB congeners (43) is also unknown.

Recognition of the importance of inhalation exposure to airborne PCBs is rising, with more emission sources identified and evidence for toxicities of the lower-chlorinated congeners mounting (44, 45). Nevertheless, key gaps are present in analytical methodology for lower-chlorinated PCBs while their toxicokinetics are poorly known, impeding the accurate assessment of potential risks. In our study, we have developed a method to measure CB11and OH-CB11s in tissue matrices. Our work shows the rate and extent of CB11 distribution and elimination after inhalation exposure and demonstrates the formation of 4-OH-CB11 in rats. The rapid elimination of this metabolite in liver and its absence in serum suggests that it is not retained in the body after exposure but rather is susceptible to further metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIEHS through grants NIH P42 ES013661 and NIH P30 ES005605. The authors thank Dr. Izabela Kania-Korwal for advice in analytical methods development and help with the GC-ECD and GC-MS instrumentation.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Tables for tissue concentrations of detected CB11 and 4-OH-CB11 expressed in ng/g wet tissue weight and ng/g lipid weight; example chromatograms of separations on GC-ECD after various cleanup treatments; and figures for comparison of time course elimination of CB11, CB8 and CB15 in body tissue. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Venier M, Hung H, Tych W, Hites RA. Temporal Trends of Persistnet Organic Pollutants: A Comparison of Different Time Series Model. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:3928–3934. doi: 10.1021/es204527q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun P, Basu I, Blanchard P, Brice KA, Hites RA. Temporal and spatial trends of atmospheric polychlorinated biphenyl concentrations near the great lakes. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:1131–1136. doi: 10.1021/es061116j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu D, Martinez A, Hornbuckle KC. Discovery of non-aroclor PCB (3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl) in Chicago air. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:7873–7877. doi: 10.1021/es801823r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JF, Wagner RE. PCB movement, dechlorination, and detoxification in the Acushnet Estuary. Environ Chem. 1990;9:1215–1233. [Google Scholar]

- 5.King TL, Yeats P, Hellou J, Niven S. Tracing the source of 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl found in samples collected in and around Halifax Harbour. Mar Pollut Bull. 2002;44:590–596. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(01)00289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi SD, Baek SY, Chang YS, Wania F, Ikonomou MG, Yoon YJ, Park BK, Hong S. Passive air sampling of polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticides at the Korean Arctic and Antarctic research stations: implications for long-range transport and local pollution. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:7125–7131. doi: 10.1021/es801004p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basu I, Arnold KA, Venier M, Hites RA. Partial pressures of PCB-11 in air from several Great Lakes sites. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:6488–6492. doi: 10.1021/es900919d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodenburg LA, Guo J, Du S, Cavallo GJ. Evidence for unique and ubiquitous environmental sources of 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl (PCB 11) Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:2816–2821. doi: 10.1021/es901155h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Litten S, Fowler B, Luszniak D. Identification of a novel PCB source through analysis of 209 PCB congeners by US EPA modified method 1668. Chemosphere. 2002;46:1457–1459. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(01)00253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrad S, Hazrati S, Ibarra C. Concentrations of Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Indoor Air and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ehters in Indoor Air and Dust in Birmingham, United Kingdom: Implications for Human Exposure. Environmental Science & Technology. 2006;40:4633–4638. doi: 10.1021/es0609147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JF., Jr Determination of PCB Metabolic, Excretion, and Accumulation Rates for Use as Indicators of Biological Response and Relative Risk. Environ Sci Technol. 1994;28:2295–2305. doi: 10.1021/es00062a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Letcher RJ, Klasso-Wehler E, Bergman A. Methyl Sulfone and Hydroxylated Metabolites of Polychlorinated Biphenyls. In: Hutzinger O, Paasivirta J, editors. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. 3K. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2000. pp. 315–359. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergman A, Klasson-Wehler E, Kuroki H. Selective retention of hydroxylated PCB metabolites in blood. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102:464–469. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lans MC, Klasson-Wehler E, Willemsen M, Meussen E, Safe S, Brouwer A. Structure-dependent, competitive interaction of hydroxy-polychlorobiphenyls, -dibenzo-p-dioxins and -dibenzofurans with human transthyretin. Chem Biol Interact. 1993;88:7–21. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(93)90081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James MO, Sacco JC, Faux LR. Effects of Food Natural Products on the Biotransformation of PCBs. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2008;25:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaminsky LS, Kennedy MW, Adams SM, Guengerich FP. Metabolism of dichlorobiphenyls by highly purified isozymes of rat liver cytochrome P-450. Biochemistry. 1981;20:7379–7384. doi: 10.1021/bi00529a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy MW, Carpentier NK, Dymerski PP, Kaminsky LS. Metabolism of dichlorobiphenyls by hepatic microsomal cytochrome P-450. Biochem Pharmacol. 1981;30:577–588. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(81)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu X, Adamcakova-Dodd A, Lehmler HJ, Hu D, Kania-Korwel I, Hornbuckle KC, Thorne PS. Time course of congener uptake and elimination in rats after short-term inhalation exposure to an airborne polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) mixture. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:6893–6900. doi: 10.1021/es101274b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Method 1668, Revision A: Chlorinated Biphenyl Congeners in Water, Soil, Sediment, and Tissue by HRGC/HRMS; EPA/821/R-00/002. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehmler HJ, Robertson LW. Synthesis of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) using the Suzukicoupling. Chemosphere. 2001;45:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(00)00546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauer U, Amaro AR, Robertson LW. A new strategy for the synthesis of polychlorinated biphenyl metabolites. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:92–95. doi: 10.1021/tx00043a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kania-Korwel I, Zhao H, Norstrom K, Li X, Hornbuckle KC, Lehmler HJ. Simultaneous extraction and clean-up of polychlorinated biphenyls and their metabolites from small tissue samples using pressurized liquid extraction. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1214:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.10.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu X, Adamcakova-Dodd A, Lehmler HJ, Hu D, Hornbuckle K, Thorne PS. Subchronic inhalation exposure study of an airborne polychlorinated biphenyl mixture resembling the chicago ambient air congener profile. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:9653–9662. doi: 10.1021/es301129h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kania-Korwel I, Shaikh NS, Hornbuckle KC, Robertson LW, Lehmler H. Enantioselective disposition of PCB 136 (2,2′,3,3′,6′6′-hexachlorobiphenyl) in C57BL/6 mice after oral and intraperitoneal administration. Chirality. 2007;19:56–66. doi: 10.1002/chir.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Philips DL, Pirkle JL, Burse VW, Bernert JT, Henderson LO, Needham LL. Chlorinated hydrocarbon levels in human serum: effects of fasting and feeding. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1989;18:495–500. doi: 10.1007/BF01055015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearson RF, Hornbuckle KC, Eisenreich SJ, Swackhamer DL. PCBs in Lake Michigan water revisited. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:1429–1436. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kania-Korwel I, Barnhart CD, Stamou M, Truong KM, El-Komy MH, Lein PJ, Veng-Pedersen P, Lehmler HJ. 2,2′,3,5′,6-Pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 95) and Its Hydroxylated Metabolites Are Enantiomerically Enriched in Female Mice. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:11393–11401. doi: 10.1021/es302810t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erickson MD. Analytical Chemistry of PCB s. 2nd. CRC Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen S, Johnels AG, Olsson M, Otterlind G, Йенсен C, Ионенльс A, Ульссон M, Оттерлинд Г. DDT and PCB in Herring and Cod from the Baltic, the Kattegat and the Skagerrak. Ambio Special Report. 1972;1:71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen S, Renberg L, Reuterqardh L. Residue analysis of sediment and sewage sludge for organochlorines in the presence of elemental sulfur. Anal Chem. 1977;49:316–318. doi: 10.1021/ac50010a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhakal K, He X, Lehmler HJ, Teesch LM, Duffel MW, Robertson LW. Identification of Sulfated Metabolites of 4-Chlorobiphenyl (PCB3) in the Serum and Urine of Male Rats. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:2796–2804. doi: 10.1021/tx300416v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundström G, Jansson B. The metabolism of 2,2′,3,5′,6-pentachlorobiphenyl in rats, mice and quails. Chemosphere. 1975;4:361–370. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warner NA, Martin JW, Wong CS. Chiral polychlorinated biphenyls are biotransformed enantioselectively by mammalian cytochrome P-450 isozymes to form hydroxylated metabolites. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;43:114–121. doi: 10.1021/es802237u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger U, Herzke D, Sandanger TM. Two trace analytical methods for determination of hydroxylated PCBs and other halogenated phenolic compounds in eggs from Norwegian birds of prey. Anal Chem. 2004;76:441–452. doi: 10.1021/ac0348672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu D, Hornbuckle KC. Inadvertent Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Commercial Paint Pigments. Environ Sci Technol. 2010:44, 2822–2827. doi: 10.1021/es902413k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanabe S, Nakagawa Y, Tatsukawa R. Absorption Efficiency and Biological Half-Life of Individual Chlorobiphenyls in Rats Treated with Kanechlor Products. Agric Biol Chem. 1981;45:717–726. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birnbaum LS. Distribution and excretion of 2,3,6,2′,3′,6′- and 2,4,5,2′,4′,5′-hexachlorobiphenyl in senescent rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1983;70:262–272. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(83)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu Z, Wong CS. Factors affecting phase I stereoselective biotransformation of chiral polychlorinated biphenyls by rat cytochrome P-450 2B1 isozyme. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:8298–8305. doi: 10.1021/es200673q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rickenbacher U, McKinney JD, Oatley SJ, Blake CC. Structurally specific binding of halogenated biphenyls to thyroxine transport protein. J Med Chem. 1986;29:641–648. doi: 10.1021/jm00155a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen DD. Toxicokinetics. In: Klaassen CD, editor. Casarett and Doull's toxicology: the basic science of poisons. 7th. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2008. pp. 305–328. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guengerich FP. Purification and characterization of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes from lung tissue. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;45:299–307. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90068-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guengerich FP, Dannan GA, Wright ST, Martin MV, Kaminsky LS. Purification and characterization of liver microsomal cytochromes p-450: electrophoretic, spectral, catalytic, and immunochemical properties and inducibility of eight isozymes isolated from rats treated with phenobarbital or beta-naphthoflavone. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6019–6030. doi: 10.1021/bi00266a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakke JE, Bergman AL, Larsen GL. Metabolism of 2,4′,5-trichlorobiphenyl by the mercapturic acid pathway. Science. 1982;217:645–647. doi: 10.1126/science.6806905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lehmann L, L Esch H, A Kirby P, W Robertson P, Ludewig G. 4-monochlorobiphenyl (PCB3) induces mutations in the livers of transgenic Fisher 344 rats. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:471–478. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ludewig G, Lehmann L, Esch H, Robertson LW. Metabolic Activation of PCBs to Carcinogens in Vivo - A Review. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2008;25:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loconto PR. Trace environmental quantitative analysis: principles, techniques, and applications. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.