Abstract

Background

During recovery from a unilateral cortical stroke, spared cortical motor areas in the contralateral (intact) cerebral cortex are recruited. Pre-clinical studies have demonstrated that compensation with the less-impaired limb may have a detrimental inhibitory effect on the intact cortical hemisphere and could impede recovery of the more-impaired limb. However, evidence from detailed neurophysiological mapping studies in animal models is lacking.

Objectives

The present study examines neurophysiological changes in the intact hemisphere of the rat following a unilateral ischemic infarct to cortical forelimb motor areas.

Methods

Eight rats were trained for two weeks on a reach and retrieval task prior to an ischemic infarct induced by the vasoconstrictor, endothelin-1 injected into the cortical grey matter encompassing the two forelimb motor representations, the caudal forelimb area (CFA) and the rostral forelimb area (RFA). Animals were randomly assigned to an Infarct/Training group (n=4) or an Infarct/No Training group (i.e., spontaneous recovery, n=4). After a five-week post-infarct period, motor areas of the intact hemisphere (CFA and RFA) were characterized using intracortical microstimulation techniques. The resulting maps of evoked movements were compared to maps derived from CFA and RFA in normal rats (Normal, n=5; Normal/Training, n=4).

Results

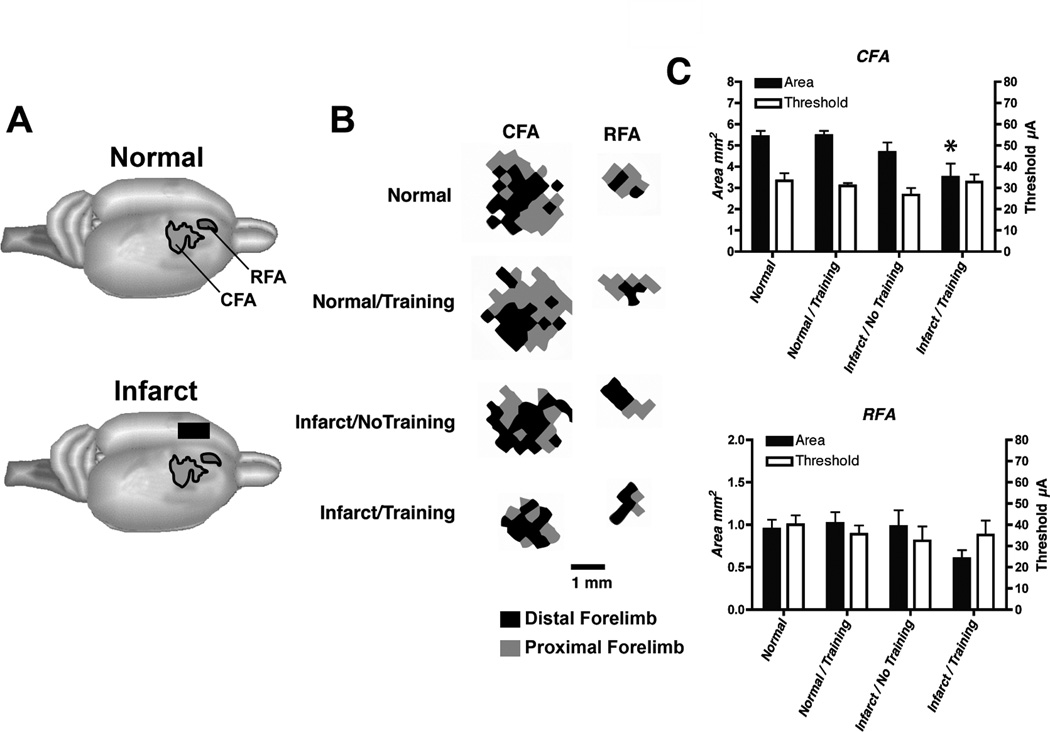

Compared with the Normal/No Training group, CFA representations were significantly smaller in the Infarct/Training group but not in the Infarct/No Training group. No significant differences were found in RFA.

Conclusions

Repetitive training of the more-impaired forelimb during the post-infarct recovery period reduces the size of motor representations in the intact hemisphere.

Keywords: Motor Rehabilitation, Interhemispheric Competition, ICMS, Motor Cortex, Ischemia

Following a unilateral stroke, spared cortical motor areas of the intact cerebral cortex in the opposite hemisphere are recruited during movement of the more impaired limb1. In considering the mechanisms underlying such reorganization, preclinical rodent models of focal ischemic injury have found a significant increase in dendritic arborization, microtubule associated protein 2, NMDA subunit 1 and FOS2 as well as crossed corticostriatal sprouting3. In the present study in adult rats, intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) techniques were used to assess functional representations of the forelimb within the intact motor cortex of the rat opposite an experimental ischemic infarct that included the rodent homolog of the primary motor cortex forelimb area (caudal forelimb area: CFA) and premotor cortex (rostral forelimb area: RFA). The results indicate that daily post-infarct training on a reach and retrieval task with the more impaired forelimb significantly reduces the overall size of the CFA, but not the RFA in the intact, contralateral hemisphere.

Seventeen adult Long Evans rats (weight ~ 470 grams; age = 5 to 6 mos) were randomly assigned to one of four groups prior to behavioral assessment on a reaching task: Infarct group with no post-infarct training (Infarct/No Training, n=4); Infarct group with four weeks post-infarct training beginning 10 days after the infarct (Infarct/Training, n=4); Normal, naïve group (Normal, n=5); Normal group with two weeks training (Normal/Training, n=4). The two normal groups were included as control groups for possible lesion and training effects. Since in this infarct model, rats cannot consistently reach out of the chamber during the first two weeks post-infarct, the 2-week Normal/Training group was included to match the experiences of the post-infarct trained rats. Each rat was singly housed within a temperature-controlled vivarium on a 12-hr:12-hr light:dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum prior to behavioral training. During training, rats were placed on a feeding schedule, while receiving ad libitum access to water. All procedures were in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Kansas University Medical Center.

Ischemic infarcts were made within CFA and RFA contralateral to the rat’s preferred forelimb for reaching by multiple intracortical injections of Endothelin-1 (ET-1; 0.3µg ET-1 dissolved in 1µl sterile saline (~120 pmol); Bachem Americas, USA), a potent vasoconstrictor2. Boreholes were made through the skull and ET-1 injected at eight locations relative to bregma: A/P, M/L (2.5, 2.5) (2.5, 3.5) (1.5, 2.5) (1.5, 3.5) (0.5, 2.5) (0.5, 3.5) (−0.5, 2.5) (−0.5, 3.5). At each location, 0.33µl ET-1 (3nl/sec) was injected at a depth of ~1.5mm below the pial surface via a micropipette (160µm o.d.) attached to a 1µl Hamilton syringe.

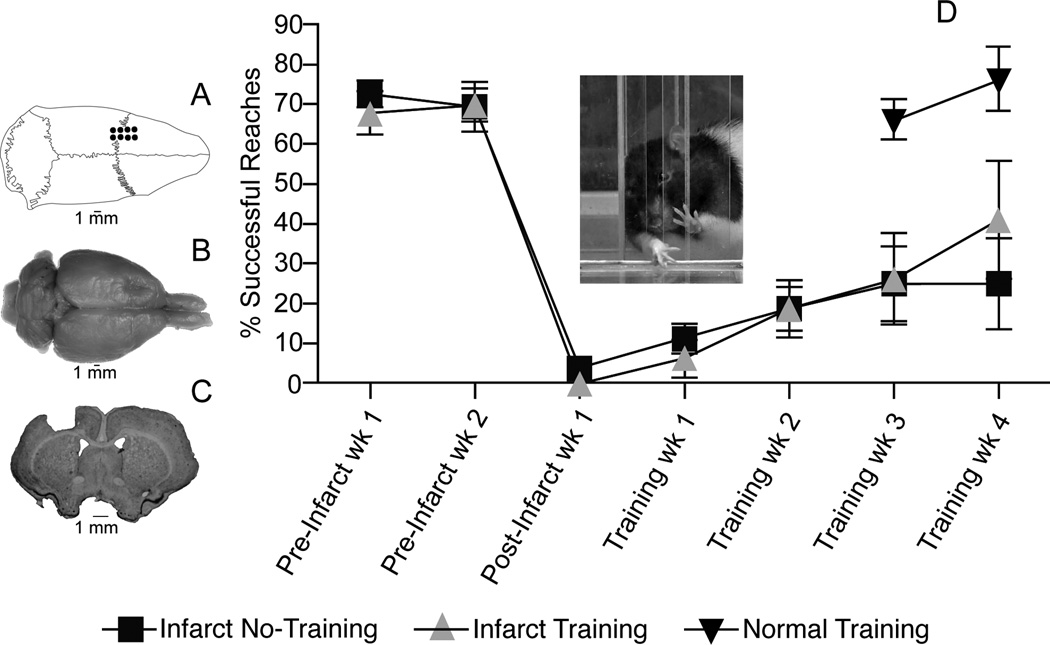

The adequacy of the ET-1 lesion upon skilled reaching performance with the forelimb contralateral to the lesion was assessed with a repeated measures ANOVA comparing performance one and two weeks prior to, and one week after the infarct. There was no significant group effect F(1,6)=0.75 (p=0.40) nor was there a significant interaction F(2,12)=0.96 (p=0.41) indicating that there were no group differences before or after the infarct. A significant effect of time F(2,12)=52.40 (p=0.0001) indicates that forelimb performance declined in both groups after the infarct. While both infarct groups showed limited recovery over the five weeks post-infarct, there was no significant difference in performance between the Infarct/Training and Infarct/No Training Groups (F(1,6) = 0.49, p=0.49).

Standard ICMS procedures4 were used to derive motor maps within CFA and RFA ipsilateral to the preferred forelimb in all groups (i.e., intact hemisphere in infarct groups). Analysis of ICMS data was performed by an ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc comparisons when appropriate. The mean stimulus threshold was similar for all four groups in both CFA (F(3,13) = 0.90; p=0.47) and RFA (F(3,13) = 0.35; p=0.79). There was a significant difference in size of CFA between groups: F(3,13)=4.75; p=0.02. Compared to the Normal group, total CFA area (distal + proximal representations) within the intact hemisphere was significantly smaller in the Infarct/Training Group (p=0.015), but not in the Infarct/No Training Group; p=0.47). There was no difference between the Normal and Normal/Training groups (p=0.99). Although RFA was also smaller in the Infarct/Training group, this difference was not significant between groups (F(3,13) = 1.95; p=0.17). When the distal and proximal representations were analyzed separately, neither distal nor proximal forelimb representations in CFA or RFA were significantly different between groups even though there was a trend for distal CFA and RFA in the Infarct/Training group to be smaller (Distal CFA: F(3,13) = 2.06, p=0.16; Distal RFA: F(3,13) = 1.94, p=0.17; Proximal CFA: F(3,13) = 1.17; p=0.36; Proximal RFA: F(3,13) = 0.55, p=0.66).

Previous studies have shown that use of the less impaired limb has an exaggerated, inhibitory influence over the damaged hemisphere after a unilateral lesion in the motor cortex of the rat5,6. The present results suggest that use of the more impaired limb may also have an inhibitory influence over the intact hemisphere. In a recent review of clinical TMS studies, Corti, Patten and Triggs7 reported several studies that demonstrated inhibition of the intact hemisphere with low frequency TMS (≤ 1 Hz) or excitation of the damaged hemisphere with high-frequency TMS (≥ 1Hz). In both paradigms, function is improved in the more impaired limb presumably by restoring interhemispheric balance.

Contradicting some previous studies8, post-infarct training did not improve motor performance. It is possible that the study was not appropriately powered to demonstrate behavioral differences between groups, but except for the latest time point, the graphs do not even suggest a trend for better performance in the trained group. Alternatively, the lack of a training effect upon functional recovery may be due to the relative large infarct employed in the present study. Typically, focal cortical infarcts employing similar methods (ET-1, pial strip, photocoagulation) and limited to CFA alone, result in transient deficits9, 10. The present study examined the effects of a larger infarct encompassing both the CFA and RFA, resulting in a substantially slower rate of spontaneous recovery and presumably maximizing the contribution of the intact, contralesional hemisphere in functional recovery. Even though training sessions were conducted daily for 28 days, the rats did not show any significant signs of improving beyond that of the non-trained rats.

Note that in Figure 1, the performance in the Infarct/Training group and the Infarct/No Training group began to diverge after the fourth week of training. It is plausible that the duration of the present training regimen could be extended to facilitate recovery. However, even with the lack of functional recovery assessed after the fourth week of training, there was a statistically significant physiological effect within the intact hemisphere. ICMS maps may provide a particularly sensitive assessment of the functional status of the intact hemisphere. If rebalancing hemispheric interactions through inhibition of the intact hemisphere accompanies recovery of function, the present results suggest that repetitive use of the impaired limb may have a beneficial effect on recovery during early stages of rehabilitation, prior to observable facilitation of performance.

Figure 1.

Motor performance after ET-1 lesion in motor cortex. A. Dorsal view of skull showing location of boreholes for ET-1 injections. B. Dorsal view of fixed brain showing location of ET-1 lesion in left motor cortex. C. Coronal section through the level of the caudal forelimb area (CFA) at bregma showing ET-1 lesion. Lesion extended through all cortical layers, but did not invade the underlying white matter. Lesion volume was derived from coronal sections imported into NIH Image J software and estimated by the Cavalieri method: Infarct/Training Group = 17.35±0.25 mm3; Infarct/No Training Group = 17.04±0.49 mm3 (p>0.05). Lesion volumes are similar to those predicted based on distribution of ET-1 injections (16mm3). D. Motor performance on single-pellet retrieval task. Rats were trained daily to reach through an opening in a Plexiglas chamber to retrieve small 45 mg food pellets (Bioserve, Frenchtown, NJ) located on a shelf placed above the floor outside the chamber (see inset)4. Once forelimb preference for unrestricted reaching was established, a movable wall inside the chamber allowed reaching with only the right or left forelimb. Food pellets were delivered one at a time for 60 trials during each session of training. A trial ended with a successful reach and retrieval to the rat’s mouth, after an unsuccessful retrieval when a pellet was contacted but not grasped, or after five failed reach attempts without contacting the pellet. A training session ended after 20 minutes regardless of the number of trials completed. Postinfarct training was conducted daily for 28 days; training for the normal group was conducted daily for 14 days (see text). Performance was assessed once per week during two weeks of baseline training, 1 week after the infarct prior to rehabilitative training and once per week after rehabilitative training.

Figure 2.

Neurophysiological maps of the caudal and rostral forelimb areas (CFA and RFA, respectively) in the contralateral, intact hemisphere after an ET-1 lesion in motor cortex. An ICMS stimulus was delivered as a train burst of 13, 0.2 ms cathodal, monophasic pulses, delivered at 350 Hz by a constant-current stimulator (Model BSI-2, BAK Electronics Inc.) at a rate of one train per second. High-resolution motor maps were derived in both CFA and RFA (350µm resolution). A. Location of CFA and RFA motor maps. B. Representational maps of CFA and RFA were delineated with customized software and analyzed quantitatively with NIH Image software. Representative maps from each group are displayed. Shown are maps derived from the right hemisphere of rats with a right forelimb preference. Distal forelimb is shown in black and proximal forelimb is shown in grey. C. Double-Y plot showing map areas and movement thresholds. Areal measurements (Mean ± SEM) of CFA and RFA in intact and infarcted rats are presented on the left y-axis. Current thresholds (Mean ± SEM) for evoking a forelimb movement in CFA and RFA are presented on the right y-axis. There were no significant threshold differences among the four groups in CFA or RFA. Only the Infarct/Training group had a significantly smaller CFA map relative to normal rats. Asterisk = p<0.05.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Grant NS30853 (RJN) and IDDRC Center Grant HD02528.

References

- 1.Bestmann S, Swayne O, Blankenburg F, et al. The role of contralesional dorsal premotor cortex after stroke as studied with concurrent TMS-fMRI. J Neurosci. 2010 Sep 8;30(36):11926–11937. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5642-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adkins DL, Voorhies AC, Jones TA. Behavioral and neuroplastic effects of focal endothelin-1 induced sensorimotor cortex lesions. Neuroscience. 2004;128(3):473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Napieralski JA, Butler AK, Chesselet MF. Anatomical and functional evidence for lesion-specific sprouting of corticostriatal input in the adult rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996 Sep 30;373(4):484–497. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960930)373:4<484::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishibe M, Barbay S, Guggenmos D, Nudo RJ. Reorganization of motor cortex after controlled cortical impact in rats and implications for functional recovery. J. Neurotrauma. 2010 Dec;27(12):2221–2232. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allred RP, Cappellini CH, Jones TA. The "good" limb makes the "bad" limb worse: experience-dependent interhemispheric disruption of functional outcome after cortical infarcts in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2010 Feb;124(1):124–132. doi: 10.1037/a0018457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allred RP, Jones TA. Maladaptive effects of learning with the less-affected forelimb after focal cortical infarcts in rats. Exp Neurol. 2008 Mar;210(1):172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corti M, Patten C, Triggs W. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of motor cortex after stroke: a focused review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012 Mar;91(3):254–270. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318228bf0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maldonado MA, Allred RP, Felthauser EL, Jones TA. Motor skill training, but not voluntary exercise, improves skilled reaching after unilateral ischemic lesions of the sensorimotor cortex in rats. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008 May-Jun;22(3):250–261. doi: 10.1177/1545968307308551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alaverdashvili M, Moon SK, Beckman CD, Virag A, Whishaw IQ. Acute but not chronic differences in skilled reaching for food following motor cortex devascularization vs. photothrombotic stroke in the rat. Neurosci. 2008 Nov 19;157(2):297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang PC, Barbay S, Plautz EJ, Hoover E, Strittmatter SM, Nudo RJ. Combination of NEP 1–40 treatment and motor training enhances behavioral recovery after a focal cortical infarct in rats. Stroke. 2010 Mar;41(3):544–549. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.572073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]