Abstract

A 33-year-old woman with a history of tubal sterilisation, presented to our gynaecological emergency unit with acute abdominal pain and signs of peritonism. The first day of her last menstruation occurred 4 weeks and 4 days before. Urine pregnancy test was positive and transvaginal ultrasound revealed an empty uterus with a heterogeneous mass below the right ovary. We performed a laparoscopy, which confirmed a previous isthmic partial salpingectomy and the presence of an ectopic pregnancy in the right distal remnant tube. Total salpingectomy of the remnant parts of the tube was performed and the postoperative course was uneventful.

Background

Worldwide, 180 million women of reproductive age undergo surgical tubal sterilisation. It is one of the most commonly used methods of contraception among women aged over 35 years.

Tubal sterilisation has been reported as one of the most successful methods of contraception with an extremely low failure rate.1 However, in case of failure, tubal sterilisation is associated with a high risk of ectopic pregnancy (implantation outside the uterine cavity) a potentially lethal condition. We present a case of an ectopic pregnancy implanted in the distal remnant tube, after laparoscopic segmental partial isthmic salpingectomy. We believe this case to be of interest for any general practitioner, who should be aware of this rare but potentially life-threatening condition.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old woman (gravida 11, para 3) was admitted to our gynaecological emergency unit with acute abdominal pain without vaginal bleeding, 4 weeks and 4 days after her last menstruation. Her medical history included laparoscopic tubal sterilisation bypartial bilateral segmental isthmic salpingectomy performed 3 years before. There was no history of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). On initial physical examination vital signs were: blood pressure 101/66 mm Hg; heart rate 79 bpm; temperature 37.1°. She was in pain and anxious but conscious and well oriented. On palpation her abdomen was tender and distended. There was tenderness in the right iliac fossa but not on the left side.

Investigations

Her urine pregnancy test was positive and the serum β subunit of the human gonadotropin hormone was 6000 IU/L. On admission the patient's haemoglobin level was 129 g/L, white cell count 8 g/L and platelet count 199 g/L.

The findings of transvaginal ultrasound were showing an empty uterus, a moderate account of fluid in the pouch of Douglas and a heterogeneous mass of 26×16 mm below the right ovary. A corpus luteum was noted in the left ovary and the endometrium thickness was 4 mm.

Differential diagnosis

Acute abdominal pain in a sterilised woman of reproductive age must raise the potential diagnosis of ovarian cyst rupture or torsion, necrobiosis of a myoma, inflammatory pelvic disease, but also non-gynaecological conditions such as appendicitis or urinary tract infections. However, complications of a possible pregnancy should be included. If pregnancy test is positive, it is mandatory to localise the pregnancy, because the risk of ectopic pregnancy is increased by the previous surgical tubal occlusion.

Treatment

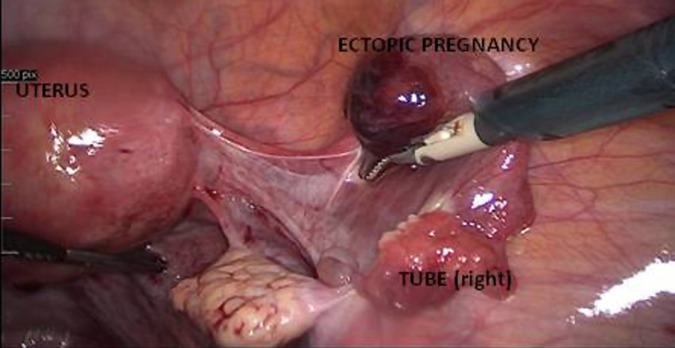

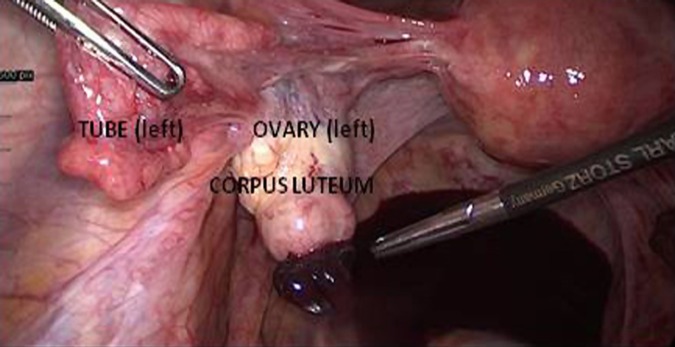

On the basis of clinical signs, urinary pregnancy test and imaging, a right ectopic pregnancy was suspected. We performed an emergency diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopic surgery. The findings revealed a bulging mass about 3 cm in diameter, at the distal end of the remnant pavilion of the right tube (figure 1). The left adnexa was normal. Total salpingectomy was performed with removal of the remnant pavilion and the ectopic pregnancy. During laparoscopy, we did not identify any fistula between the uterine horn and the peritoneal cavity nor tubal spontaneous reanastomosis (figures 1 and 2). However, we could notice a discrete exudation of a serous fluid coming from the right horn, without any sign of rupture or dehiscence, therefore explaining potential passage of sperm in the peritoneal cavity.

Figure 1.

An emergency diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopic surgery was performed. The findings revealed a bulging mass about 3 cm in diameter, at the distal end of the remnant pavilion of the right tube.

Figure 2.

During laparoscopy, no fistula was identified between the uterine horn and the peritoneal cavity nor tubal spontaneous reanastomosis.

Outcome and follow-up

Histopathological examination of the laparoscopic specimens confirmed right distal tubal pregnancy. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged the following day.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first case report describing ectopic pregnancy in the distal remnant tube, after laparoscopic partial segmental isthmic salpingectomy. We found few case reports of ectopic pregnancies occurring after sterilisation, and published cases neither report the surgical technique used for tubal occlusion nor the localisation in the remnant tube.2–5 Tubal sterilisation prevents pregnancy by occluding or disrupting tubal patency. It can be performed during caesarean section or early postpartum through the umbilicus, but also as an interval procedure by laparoscopy or by hysteroscopy. Although tubal ligation is highly effective and considered as a definitive method of contraception, the risk of failure is estimated to be close to 1%.1 There are few retrospective trials on incidence and long-term outcomes of tubal sterilisation methods, with short follow-up because of the assumption that any failure would occur soon after surgery. The largest study is the US Collaborative Review of sterilisation (CREST study). In the CREST Study, 10 685 women who underwent tubal sterilisation were registered from 1978 to 1986 and followed up until 1994. The 10-year cumulative pregnancy rate was 18.5/1000 women and among these pregnancies approximately 30% were ectopic.6 7 This study suggests that the risk of pregnancy persists many years after tubal sterilisation. Factors that are believed to contribute to the failure of tubal sterilisation include: type of surgical method, and age of the patient at the time of the procedure.1 8 In particular, they found that the highest proportion of ectopic pregnancies was among women who underwent bipolar coagulation (65%), followed, in decreasing order, by partial salpingectomy (43%), silicone band application (29%), unipolar coagulation (17%) and clip application (15%).The 10 year cumulative probability of pregnancy was low for most women aged 34–44 years at sterilisation but as high as 5% for women aged 18–27 years. There are several theories to explain sterilisation failure. Tubal recanalisation and cornual/tuboperitoneal fistula formation are the main explanations.9

In conclusion, we believe this case to be of interest for any general practitioner who should be aware of this rare but potentially life-threatening condition. Any woman of reproductive age presenting with abdominal pain should at least have a urinary pregnancy test, even if she had previous tubal sterilisation. If pregnancy test is positive, the practitioner should be aware of the high risk of ectopic pregnancy and refer the patient to the specialist in emergency.

Learning points.

Urinary pregnancy test should be performed in any woman presenting with abdominal pain during reproductive age, even if she had previous tubal sterilisation.

Pregnancies occurring after sterilisation are more likely to be ectopic.

Sterilisation technique and age of the patient at the time of the procedure are major risk factors, participating to failure.

Ectopic pregnancy is a life-threatening condition and needs to be treated in emergency.

Footnotes

Contributors: PD conceived the idea, wrote the article and reviewed the literature. OJ reviewed the literature. PP conceived the idea and was involved in planning. PD was involved in planning and conducting the treatment procedure of the patient.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Peterson HB. Sterilization. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:189–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janjua A, Beasley J. Ectopic pregnancy after caesarean section sterilisation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;147:114–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu S, Ding DC. Ovarian pregnancy in a woman after postpartum tubal ligation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006;124:121–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oruc S, Karaer O, Goker A. Ectopic pregnancy following tubal sterilisation: a case report. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:827–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumbak B, Ozkan ZS, Simsek M. Heterotopic pregnancy following bilateral tubal ligation: case report. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2011;16:319–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson HB, Xia Z, Hughes JM, et al. The risk of ectopic pregnancy after tubal sterilization. US Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. N Engl J Med 1997;336:762–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson HB, Xia Z, Hughes JM, et al. The risk of pregnancy after tubal sterilization: findings from the US Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:116–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrie TA, Nardin JM, Kulier R, et al. Techniques for the interruption of tubal patency for female sterilisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011(2):CD003034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Awonuga AO, Imudia AN, Shavell VI, et al. Failed female sterilization: a review of pathogenesis and subsequent contraceptive options. J Reprod Med 2009;54:541–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]