Abstract

A young child presented to the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital with on and off headache, focal seizures involving the left side of the body, weakness of left upper and lower limbs and vomiting for 2 weeks. Examination showed an alert child with grade 4/5 powers in left upper and lower limbs. Blood investigations were normal. An urgent CT of the brain showed intra-axial mass in the right frontal cerebral cortex, superolateral to the right lateral ventricle. MRI of the brain showed supratentorial extraventricular mass of 5.20×3.70×3.80 cm, in the right frontal cortex, emitting heterogeneous signals on T1, T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences and impression of astrocytoma, ependymoma or choroid plexus papilloma was made. Complete surgical resection of mass was performed. Histopathology of the mass proved it as WHO grade III anaplastic ependymoma. The child made an uneventful postoperative recovery and radiotherapy was followed.

Background

Ependymal lining cells of ventricular system and central canal of the spinal cord usually give rise to ependymomas.1 Supratentorial ependymoma is a rare entity with variable clinical course.2 In small number of cases, ependymomas arise from supratentorial parenchyma. Only few cases are reported in the literature.3––5 T1-weighted MRI shows isointense to hypointense signal and the mass is hyperintense on T2 and proton density-weighted MRIs. Gold standard is pathological diagnosis with histopathology showing perivascular pseudorosettes and rosettes. The tumour cells are positive glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), S100 protein and vimentin. Our patient showed a more aggressive tumour, WHO grade III. Less than five anaplastic ependymomas were reported previously. Complete surgical resection of the tumour is the best option. Postoperative radiotherapy shows better outcome.6 7

Case presentation and investigations

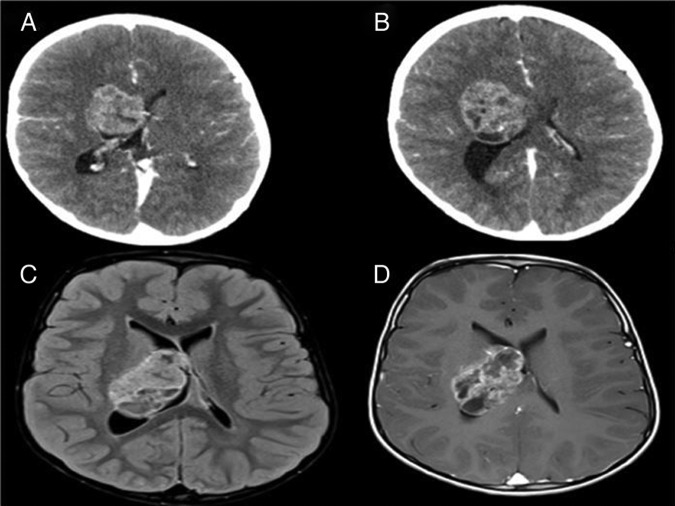

A 2-year-old boy presented to emergency department with headache for 4 months, increasing frequency of focal seizures involving the left side of the body, weakness of left upper and lower limbs and vomiting for 2 weeks. Examination showed alert child with grade 4/5 power in left upper and lower limbs; the rest of examinations were normal except for papilloedema on funduscopy. White cell count, serum chemistry was normal. A CT of the brain (figure 1A,B) showed a heterogeneously enhancing intra-axial mass in the right cerebral hemisphere, arising from superolateral aspect of the right lateral ventricle and extending into adjacent brain parenchyma. The mass was showing multiple cystic areas. MRI of the brain (figure 1C,D) revealed that the margins of mass were slightly better appreciated and it was lobulated. It again appeared heterogeneous in morphology with heterogeneous postcontrast enhancement.

Figure 1.

CT and MRI of the brain showing heterogeneous right cerebral hemisphere intra-axial mass adjacent to lateral ventricle with bulging component into the ventricular margins.

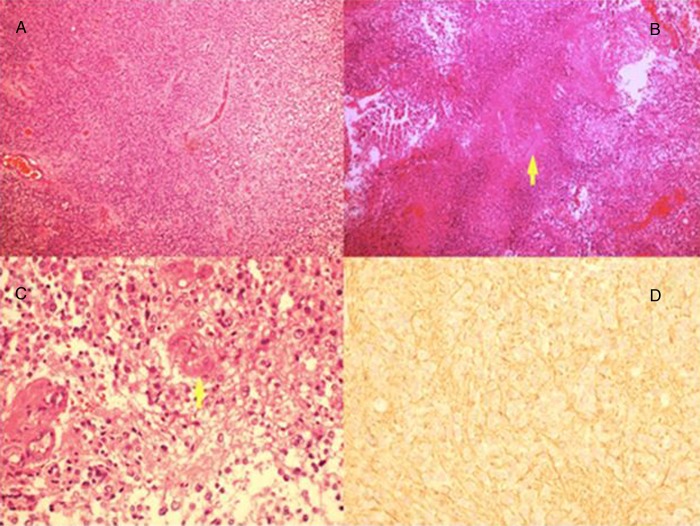

Biopsy and histopathological study of the mass was performed. H&E-stained section (figure 2) shows tumour cells with extensive necrotic area, and nests of tumour cells arranged around blood vessels forming rosettes. Individual cells are small with nuclear atypia and pleomorphism. There is a focus of endothelial hyperplasia in a small vessel (figure 2C,D). GFAP immunohistochemical stain is negative in tumour cells but positive in fibrillary processes around them (figure 2D). Ki67 proliferation index was 10%, proving it to be WHO grade III anaplastic ependymoma.

Figure 2.

(A) H&E-stained section at ×10 magnification showing nests of tumour cells arranged around blood vessels forming rosettes. Individual cells are small with rounded hyperchromatic nuclei. (B) Tumour cells with extensive necrotic area. (C) H&E-stained section showing tumour cells with nuclear atypia and pleomorphism. There is a focus of endothelial hyperplasia in a small vessel. (D) Glial fibrillary acidic protein immunohistochemical stain which is negative in tumour cells but positive in fibrillary processes around them.

Treatment

Complete surgical resection of tumour was conducted and the child made an uneventful postoperative recovery. Then radiotherapy was followed.

Discussion

Cells lining the ventricular system or central canal in the spinal cord usually give rise to ependymomas.1 In children ependymomas represents about 6–12% of all paediatric brain tumours and are located predominantly in the posterior fossa.8 Intracranial ependymomas can arise along ventricular system or extraventricular tissue. Supratentorial ependymoma involving cerebral tissue is a rare entity.9 They can appear at any age; cases were documented between ages of 1 and 81 years without any gender predilection. In cases of supratentorial ependymomas, symptoms are mild despite large size of tumour in the cerebral hemisphere.10 11 Astrocytoma, supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumour, ganglioma, gangliocytoma and oligodendroglioma are the main differentials of supratentorial ependymomas involving ventricular system.12 In supratentorial ependymomas, unenhanced CT of the brain shows isoattenuation to slight hypoattenuation of surrounding normal brain tissue.10 On unenhanced T1-weighted MRI they are isointense to hypointense relative to normal white matter and hyperintense on T2 and proton density-weighted MRIs. Heterogeneous focal signals within solid tumour represent calcification, necrosis, haemosiderin or methaemoglobin. Young age, incomplete tumour resection, histological anaplasia and supratentorial localisation are negative prognostic factors.4 Anaplastic ependymomas have a tendency to disseminate within the central nervous system (CNS) through cerebrospinal fluid.13 Even after tumour resection, follow-up CNS MRI is mandatory in adult patients with anaplastic ependymoma. Ependymomas tend to grow back locally if they recur after treatment. Gold standard is the pathological diagnosis. Perivascular pseudorosettes and ependymal rosettes are the key histological features. Expression of GFAP, S100 protein and vimentin is the typical feature of ependymomas. Neural antigens are not expressed in GFAP immunoreactivity.8 The clinical course of ependymoma correlates with measurement of cellular proliferative ability of Ki67–MIB1 index; in our case, it is 10%, which corresponds to WHO grade III ependymoma.14 Less than five anaplastic ependymomas were reported previously.15 WHO classified ependymomas into four types: myxopapillary ependymomas, subependymomas, ependymomas and anaplastic ependymomas.16 Although total resection is optimal, it is only possible in approximately 30–40% of cases because vital structures are frequently involved by the tumour.17 A highly favourable prognosis is expected after complete tumour resection, which is confirmed by postoperative MRI or CT scan.17 Owing to the fact that our case had a high-grade tumour, the patient received radiotherapy after postradical excision with good recovery of neurological symptoms. Several clinical studies have demonstrated that patients with ependymoma who are treated with postoperative radiation have a better outcome.6 7 Chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin have some activity against ependymomas but due to side effects of hearing loss and kidney damage, carboplatin was used in some cases with variable response.18 A study showed that ependymal tumours expressed MDR1 gene in 95% of cases, which was responsible for its resistance to chemotherapeutic agents.19

Learning points.

Anaplastic ependymoma in children is rare in supratentorial region.

For diagnosis, CT scan and MRI are helpful but histopathology is the gold standard.

Complete surgical removal with postoperative radiotherapy has a better outcome.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Barone BM, Elvidge AR. Ependymomas. A clinical survey. J Neurosurg 1970;33:428–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oya N, Shibamoto Y, Nagata Y, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for intracranial ependymoma: analysis of prognostic factors and patterns of failure. J Neurooncol 2002;56:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamano E, Tsutsumi S, Nonaka Y, et al. Huge supratentorial extraventricular anaplastic ependymoma presenting with massive calcification—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2010;50:150–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roncaroli F, Consales A, Fioravanti A, et al. Supratentorial cortical ependymoma: report of three cases. Neurosurgery 2005;57:E192 discussion E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swartz JD, Zimmerman RA, Bilaniuk LT. Computed tomography of intracranial ependymomas. Radiology 1982;143:97–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mork SJ, AC L. Ependymoma: a follow-up study of 101 cases. Cancer 1977;40:907–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shuman RM, Alvord EC, RW L. The biology of childhood ependymomas. Arch Neurol 1975;32:731–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teo C, Nakaji P, Symons P, et al. Ependymoma. Childs Nerv Syst 2003;19:270–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwamoto N, Murai Y, Yamamoto Y, et al. Supratentorial extraventricular anaplastic ependymoma in an adult with repeated intratumoral hemorrhage. Brain Tumor Pathol. Published: Apr 2013. 10.1007/s10014-013-0146-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis MJ, Hasan F, Weinreb I, et al. Extraventricular anaplastic ependymoma with metastasis to scalp and neck. J Neurooncol 2011;104:599–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehtesham M, Kabos P, Yong WH, et al. Development of an intracranial ependymoma at the site of a pre-existing cavernous malformation. Surg Neurol 2003;60:80–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molina OM, Colina JL, Luzardo GD, et al. Extraventricular cerebral anaplastic ependymomas. Surg Neurol 1999;51:630–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito R, Kumabe T, Kanamori M, et al. Dissemination limits the survival of patients with anaplastic ependymoma after extensive surgical resection, meticulous follow up, and intensive treatment for recurrence. Neurosurg Rev 2010;33:185–91, discussion 91–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma L, Xiao S-Y, Liu X-S, et al. Intracranial extraaxial ependymoma in children: a rare case report and review of the literature. Neurol Sci 2012;33:151–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero FR, Zanini MA, Ducati LG, et al. Purely cortical anaplastic ependymoma. Hindawi Publishing Corporation, Case Rep Oncol Med 2012;2012:541431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiestler O, Schiffer D, Coons S, et al. Ependymal tumors. In: Kleihues P, Cavenee W. eds. Tumors of the central nervous system. Lyon, France: IARCPress, 2000:72–82 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nazar G, Hoffman H, Becker L, et al. Infratentorial ependymomas in childhood; prognostic factors and treatment. J Neurosurg 1990;72:408–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouffet E, Foreman N. Chemotherapy for intracranial ependymomas. Childs Nerv Syst 1999;15:563–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou P, Barquin N, Gonzalez-Crussi F, et al. Ependymomas in children express the multidrug-resistance gene: immunohistochemical and molecular biologic study. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med 1996;16:551–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]