Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has become a curative treatment for patients with a wide variety of diseases [1, 2], with approximately 25,000 allogeneic HSCTs performed annually worldwide [3]. The increasing number of stem cell transplants performed reflects a greater availability of donors from acceptable transplant sources (umbilical cord, unrelated donors, haploidentical donors) and the breadth of indications for this treatment. The availability of reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens has also extended this treatment option to individuals who are older and those with comorbidities. At the same time, improvements in human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matching, prevention and treatment of post-transplant infections, and more effective management of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGvHD) have played a significant role in extending HSCT survivorship [4]. Although survivorship after life-threatening illness is a benefit, at the same time, late effects of HSCT including cGvHD, opportunistic infections, and the management of minimum residual disease are challenges that can be difficult to manage and contribute to the need for specialized long-term follow-up [5].

Beyond the clinical aspects of recovery, survivorship also entails a reintegration back into domestic and professional roles and meaningful routines and activities that generate a sense of well-being and quality of life. The assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQL) includes biological factors along with functional status, symptom experience, general health perceptions, and overall quality of life [6]. Several recent reviews have examined HRQL after transplant [7, 8] including one focused specifically on the experiences of long-term survivors of allogeneic HSCT [9]. Although current evidence suggests that most survivors experience a relatively good HRQL when compared to healthy populations, or to other chronically ill populations, a subset of survivors report impaired physical or emotional function [10–13]. Major demographic, clinical and treatment factors influencing variation in HRQL outcomes are well described [14] including the unique complications and late effects, such as cGvHD and infections associated with prolonged immunosuppression therapy, which substantially shape the recovery experienced by long-term survivors [15–17]. However, no prior studies have evaluated physical and mental health status and HRQL longitudinally in a diverse sample of allogeneic HSCT recipients during a period of extended survival. This study characterizes patterns of recovery according to health status and HRQL in a diverse population of survivors ≥ 3 years after allogeneic HSCT, and identifies predictors of impairment in these outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

The design of this prospective longitudinal study has been previously described [18]. This study was approved by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute intramural Institutional Review Board and all patients provided written informed consent before participation. Patients who were three years following first allogeneic HSCT (after receiving either a myeloablative [19] or RIC [20–22] conditioning regimen) at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center were accrued consecutively. Eligible study participants were at least 18 years old, carried a life expectancy of at least 6 months, and spoke and read English or Spanish. Those with a life expectancy less than six months and individuals who had undergone a second allogeneic HSCT procedure were excluded from participation. Those who agreed to join the study completed a survey packet annually within 60 days of their annual clinical follow-up.

Study Procedures

Paper and pencil questionnaires, which took approximately 45 minutes to complete, were administered to outpatients in a private area. In some instances, the questionnaires were mailed with instructions for completion and a postage-paid return envelope. If the questionnaires were not returned within two weeks, a follow-up phone call was made to confirm receipt of the questionnaires and respond to any questions or concerns about completion. Permission to contact participants by phone and e-mail was obtained during the consenting process.

Measures

Physical and mental health status were measured using the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Short Form 36-Version 2 (SF-36v2) [23]. The SF-36 is a 36-item self-report measure of physical and mental health, evaluating 8 subscales including: physical functioning, physical role functioning, emotional role functioning, social functioning, bodily pain, mental health, vitality, and general health. In addition to the individual subscale scores, a physical component summary score (PCS) and mental component summary score (MCS) are computed through aggregation of the subscales. To facilitate comparison with U.S. healthy population values, summary and subscale scores were transformed to a T-score metric, with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. Higher scores indicate better outcomes [23]. Summary scores that are 3 or more points above or below the norm-based score of 50, the minimum important difference (MID) indicating clinical relevance, are considered outside the average range for the U.S. healthy population. The SF-36 was translated into Spanish through the International Quality of Life Assessment Project. Strong evidence of internal consistency reliability and construct validity has been documented in Spanish-speaking samples [24–27].

HRQL was measured with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General Version 4 (FACT-G). The FACT-G is a 27-item self-report cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire. Scores are summed to yield a FACT-G Total Score, which can range from 0–108. Higher scores indicate better HRQL. The U.S. healthy population value for the FACT-G total score is 80.1 (±18.1) and a 5 point difference is considered clinically meaningful [28]. The Spanish version of the FACT-G (version 4) has demonstrated construct validity and evidence of strong internal consistency reliability [29, 30].

Physical symptom distress was assessed with the physical symptom distress scale (PSDS) of the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (RSCL) [31]. The PSDS consists of 23 items evaluating the bother experienced in the past 30 days from a range of physical symptoms. Total PSDS scores range from 23–92; higher scores indicate more symptom distress. The PSDS raw scores were linearly transformed into scores on a 100 – point scale; previously published data [31] suggests three cut-points that may be used to aid interpretation. Thus, a transformed score of < 10 was considered “low” (e.g. healthy population), 10–15 as “mild/moderate” (i.e. disease free population; newly diagnosed), and > 15 as “high” (i.e. active treatment; high symptom burden cancer type). The Spanish version of the RSCL has demonstrated strong internal consistency reliability and construct validity in Spanish-speaking cancer patients [10].

Demographic (age, gender, race and ethnicity, years post-transplant, country of residence, marital status, educational attainment, employment) and clinical (intensity of conditioning, HLA compatibility, stem cell source, primary disease, stage of disease, co-morbidity score) variables were collected at time of study enrollment. Transplant risk status was classified based on an expanded version of published guidelines [32] to yield three risk categories based on type of malignancy/disease and stage at the time of transplant: standard, intermediate, high/very high. Comorbidities at time of transplant were retrospectively scored using the HCT-CI index [33], and categorized according to whether 0, 1–2, or ≥ 3 comorbidities were present. Several additional clinical variables were also collected annually and modeled as time-varying factors. These variables included Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, evidence of disease, current treatment with systemic immunosuppression, and physical symptom distress. Evidence of disease was coded based on molecular, hematopathologic or radiographic evidence of disease and whether treatment had been administered for their primary disease in the past year. Only subjects in complete remission (CR) and who had not received treatment for their primary disease in the past year were coded as “no evidence of disease”. If a subject was receiving any immunosuppressive therapy, including single agent prednisone, they were classified as positive for the presence of immunosuppression (compared to none) [17, 34–36].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe clinical and demographic characteristics of subjects and to summarize health status, HRQL, and physical symptom distress scores at each year following allogeneic HSCT. Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) was used to analyze within-individual (level-1) and between-individual (level-2) changes. The main goal of HLM models was to examine changes over time in longitudinal data, and therefore time was included in all models.

For each of the three outcomes variables (PCS, MCS, and FACT-G) HLM was performed in two steps. First, three unconditional models were specified: unconditional means model (no time effect), unconditional linear model (linear time effect), and unconditional quadratic model (quadratic time effect). The main purpose of fitting the unconditional means models is to estimate level-1 and level-2 variance components. This allows for a determination of whether significant between-individual variability exists in the trajectories for physical health, mental health, or HRQL which may be accounted for by level-2 covariates [37]. If the level-2 variance components are significant, suggesting substantial between-individual variability in the intercept or trajectory, demographic and clinical variables significant in the uncontrolled model, along with the baseline clinical factors are then examined in an adjusted model. The deviance goodness-of-fit test was used to compare the model fit of the linear and quadratic time effect models. Subsequently, each time-invariant (age, gender, education, ethnicity, marital status, disease risk status, conditioning type, and HCT-CI category) and time-varying (evidence of disease, treatment with systemic immunosuppression, and physical symptom distress) covariate was tested one by one to see if it alone was a significant level-2 predictor of the outcome. Two HLM models were specified to sequentially investigate the association of the covariates with the three outcomes. Model 1 included demographic and baseline clinical variables: age, gender, ethnicity, transplant risk status, co-morbidity, and conditioning type. The final model (model 2) included all other time-invariant and time-varying variables that were significant at the intercept or linear term in the individual models, in addition to the covariates from model 1.

All models were estimated using full information maximum likelihood estimation. The unstructured covariance matrix was used for random intercepts and slopes in each model. A p-value < .05 indicated statistical significance. All data analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 [38].

Results

Study Participants

Beginning in August 2005, two hundred and twenty-seven HSCT survivors were screened and 173 agreed to participant and completed the enrollment (baseline) survey. Fifty-four patients were not enrolled due to lack of interest (n=10), clinical acuity/second HSCT (n=16), limited literacy or speaking a language other than English or Spanish (n=24). Data collection at subsequent time points included: second year questionnaires (n=154), third year questionnaires (n=106), fourth year questionnaires (n=73), fifth year questionnaires (n=53) and sixth year questionnaires (n=1) until study closure in December 2010 (n=139 remained on study). Attrition was due to death (n=17), participant withdraw/lost to follow-up (n=10), clinical acuity/2nd HSCT (n=7).

Adult participants (N=171) with complete enrollment data were primarily male (62.6%), married (64.1%), and racially/ethnically diverse (40% Hispanic; 10% Asian; 8% Black) (table 1). At time of enrollment, subjects were on average 5.19±2.93 years following a myeloablative allogeneic HSCT (55%) from a matched sibling donor (98.8%) for leukemia (55.6%). The majority of participants were in a CR (83%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Demographic Characteristics† | All Participants N=171; (n %) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) mean (SD)*** | 44.5 (13.45) |

| [range] | [19–76] |

| Sex (male) | 107 (62.6) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 69 (40.4) |

| Non-Hispanic | |

| White | 65 (38.0) |

| Asian | 18(10.5) |

| Black | 15 (8.8) |

| Mixed | 4 (2.3) |

| Residency1*** | |

| Always in U.S. | 68 (40.7) |

| Stayed in U.S. after HSCT | 42(25.1) |

| Left U.S. after HSCT | 57(34.1) |

| Marital Status (married)2 | 109(64.1) |

| Education3** | |

| Through High School Graduate | 48 (28.4) |

| Some College/Associate's Degree | 43 (25.4) |

| Bachelor's Degree | 35 (20.7) |

| Graduate | 43 (25.4) |

| Employment3 | |

| Full-time | 69 (40.8) |

| Part-time | 37(21.9) |

| Student | 11(6.5) |

| Not Working | 52(30.8) |

| Clinical Characteristics | Pre-Transplant |

| HCT-CI Score | |

| 0 Score | 55(32.1) |

| 1 or 2 Score | 55(32.1) |

| >=3 Score | 61 (65.7) |

| Transplant Risk Status | |

| Low | 92(53.8) |

| Intermediate | 35 (20.5) |

| High/Very High | 44(25.7) |

| Primary Disease | |

| Acute Leukemia | 33(19.3) |

| Chronic Leukemia | 62 (36.3) |

| Lymphoma/MM | 39 (22.8) |

| MDS | 17 (9.9) |

| Non-Hematological Malignancy | 14 (8.2) |

| Solid Tumor | 6(3.5) |

| Conditioning Regimen*** | |

| RIC | 76 (44.4) |

| Myeloablative | 95 (55.6) |

| Stem Cell Source | |

| Peripheral Blood | 166(97.1) |

| Bone Marrow | 5 (2.9) |

| HLA Compatibility | |

| Matched Sibling | 169(98.8) |

| Syngeneic | 2(1.2) |

| Clinical Characteristics | Study Enrollment |

| Evidence of Disease 4*** | 34(19.9)1 |

| Disease Status | |

| CR | 142(83.0) |

| PR/Stable/MRD/Molecular Relapse | 17 (9.9) |

| PD/Hematologic Relapse | 12 (7.0) |

| Receiving Active Treatment | 19(11.1) |

| Immunosuppression Intensity | |

| None | 114(66.7) |

| Mild | 7(4.1) |

| Moderate | 40(23.4) |

| High | 10(5.8) |

| cGVHD Severity | |

| None | 97 (56.7) |

| Mild | 43(25.1) |

| Moderate | 26(15.2) |

| Severe | 5 (2.9) |

| ECOG Performance Status | |

| Grade 0 | 138(70.8) |

| Grade 1 | 32(18.7) |

| Grade 2 | 1 (0.6) |

| Time since HSCT (years), mean (SD) | 5.19(2.93) |

| [range] | [3 – 16] |

| median | 4.0 |

Abbreviations: MM, multiple myeloma; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; MRD, minimal residual disease; PD, progressive disease; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HCT-CI, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation - comorbidity index; SD, standard deviation; HSCT, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation; cGVHD, chronic graft versus host disease.

NOTE:

p<.01;

p<.001. Hispanic subjects were significantly younger, less educated, had less evidence of disease and more likely to have residency outside of the US and to have a myeloablative HSCT.

At study enrollment.

n=167;

n=170;

n=169.

Of those classified as having evidence of disease, 5 (14.7%) had achieved a CR but were continuing a course of disease specific treatment.

Unadjusted baseline means for PCS, MCS, and FACT-G in the pooled sample and for subgroups who were 3, 4–6 years or 7 or more years post-transplant were compared to U.S. healthy population values (table 2). In the pooled sample, mean scores were descriptively within the expected range (norm-based scores 47–53) for PCS and MCS. At enrollment, approximately one third of the sample reported PCS (n=65, 38%) and MCS (n=59, 34.5%) scores that suggest impairments that were clinically relevant (≤ 47). Similarly, FACT-G scores consistently exceeded the population mean, with slightly less than one fifth of the respondents (n=34, 19.9%) reporting scores suggesting clinically relevant impairment (≤ 75.1). The mean PSDS scores were within a range comparable to cancer patients receiving active treatment (> 15).

Table 2.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Mean (SD) [range] at Study Enrollment

| All Participants1 (N=171) |

3 years post- HSCT (n = 78) |

4–6 years post- HSCT (n = 50) |

7+ years post- HSCT (n = 43) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-362 | ||||

| Physical Function | 46.97 (10.08) | 47.76 (8.26) | 45.22 (12.35) | 47.06 (10.27) |

| [14.94–57.03] | [27.57–57.03]* | [14.94–57.03]* | [25.47–57.03]* | |

| Role Physical | 45.67 (10.04) | 46.28 (9.07) | 43.51 (11.72) | 46.42 (9.49) |

| [17.67–56.85] | [20.12–56.85]* | [17.67–56.85]* | [22.57–56.85]* | |

| Bodily Pain | 51.27 (9.67) | 51.01 (8.82) | 50.89 (11.00) | 52.15 (9.61) |

| [19.86–62.12] | [29.15–62.12]* | [19.86–62.12]* | [29.15–62.12]* | |

| General Health | 47.68 (10.44) | 48.38 (9.85) | 46.10 (11.82) | 48.18 (9.91) |

| [21.95–63.90] | [21.95–63.90]* | [23.38–63.90]* | [26.90–63.90]* | |

| Vitality | 53.22 (9.61) | 53.53 (9.67) | 52.41 (10.10) | 53.06 (8.92) |

| [23.99–70.82] | [30.24–70.82]* | [23.99–70.82]* | [33.36–70.82]* | |

| Social Function | 47.75 (10.04) | 46.80 (10.73) | 47.28 (10.82) | 49.58 (7.49) |

| [13.22–56.85] | [18.67–56.85]* | [13.22–56.85]* | [29.58–56.85]* | |

| Role Emotional | 45.50 (10.98) | 45.65 (10.62) | 44.22 (12.82) | 45.98 (9.41) |

| [9.23–55.88] | [17.01–55.88]* | [9.23–55.88]* | [28.67–55.88]* | |

| Mental Health | 50.37 (9.93) | 49.86 (10.75) | 50.29 (10.24) | 51.01 (7.98) |

| [19.03–64.09] | [19.03–64.09]* | [21.85–64.09]* | [33.11–64.09]* | |

| PCS3 | 47.84 (9.69) | 48.65 (7.61) | 46.14 (11.90) | 48.37 (10.16) |

| [19.90–66.33] | [28.38–61.05]* | [19.90–66.33]* | [20.35–61.66]* | |

| MCS3 | 49.39 (10.11) | 48.93 (10.73) | 49.34 (10.61) | 50.29 (8.40) |

| [24.36–69.59] | [26.66–62.63]* | [24.36–69.59]* | [34.74–67.46]* | |

| FACT-G4 | 86.86 (15.88) | 86.69 (15.90) | 86.62 (18.10) | 87.47 (13.08) |

| [31.0–108.0] | [43.67–107.0]* | [31.0–108.0] | [50.0–108.0]* | |

| RSCL5 | 15.54 (11.14) | 16.00 (12.05) | 15.39 (11.43) | 14.86 (9.10) |

| PSD | [0–53.62] | [0–53.62] | [0–50.72] | [0–33.33] |

Abbreviations: SF-36, Short-Form 36 Health Survey; PCS, Physical Component Score:; MCS, Mental Component Score; FACT-G, Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy-General; RSCL, Rotterdam Symptom Checklist; PSD, Physical Symptom Distress; SD, standard deviation; HSCT, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

NOTE:

Years post-HSCT were grouped to the nearest year including all observations ± 6 months, observations at exactly 6 months were rounded up.

Normed to the 1998 U.S. healthy population: M=50, SD=10 22.

n=167.

n=168, reference values for 1998 U.S. healthy population of adults M=80.1, SD=18.123

Transformed to 0–100 scale; scores < 10 suggest "low" symptom distress (e.g. healthy population) and >15 suggest "high" symptom distress (i.e. active treatment), 'missing cases.

missing cases.

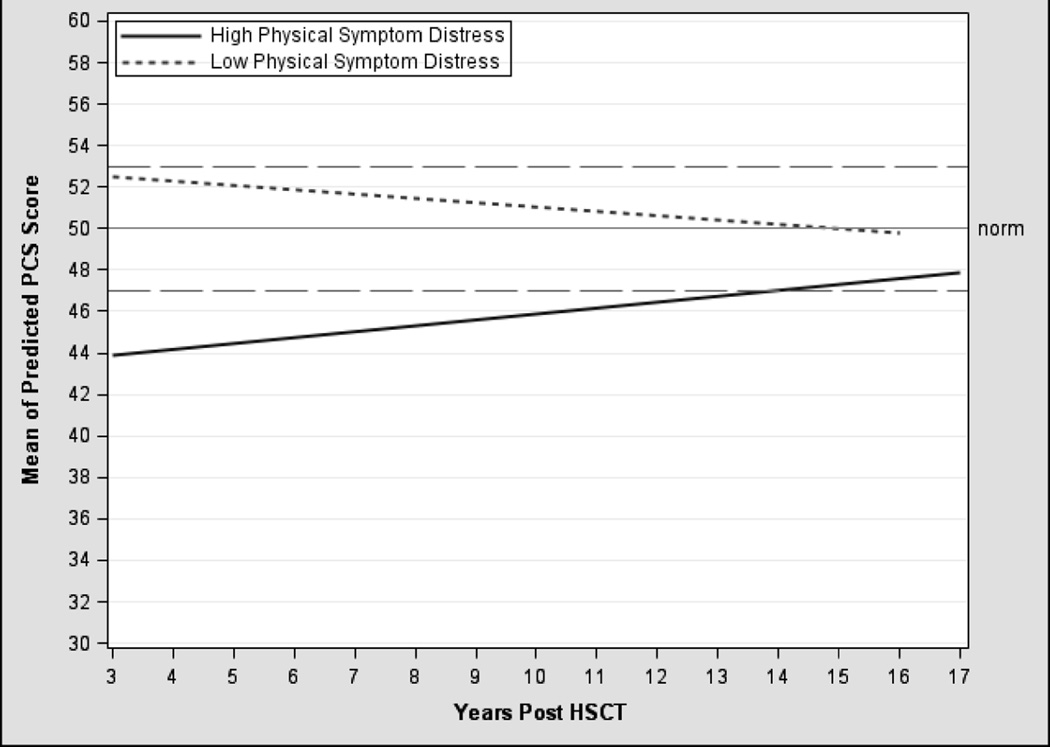

Physical Health

The unconditional PCS model demonstrated no significant change in the trajectory of physical health (p ≥ 0.05) although the variance components (intercept, linear rate of change, within-person variability) were significant (table 3). In the final model (model 2), three time-varying predictors (evidence of disease, intensity of immunosuppression, physical symptom distress) explained additional variability in baseline physical health and its rate of change. After controlling for demographic and clinical covariates, receiving systemic immunosuppression for the treatment of cGvHD at any point post-transplant significantly predicted impairments in physical health (B= −2.85, p < 0.001). In addition, symptom distress predicted physical health differently based on the level of distress and time post-transplant (interaction term B=0.03; p < 0.05). Relative to age-matched normative values, survivors with high symptom distress reported persistent impairments in physical health that remained clinically meaningful up to 14 years post-transplant; although the effect lessened over time (figure 1). In contrast, those with low symptom distress remained within a range consistent with healthy population values, despite a slight downward trend over time. Overall, survivors with high symptom distress and/or those receiving systemic immunosuppression experienced impairments in physical health (table 5).

Table 3.

Final Hierarchical Linear Model for PCS and MCS

| PCS | MCS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional | Conditional | Unconditional | Conditional | |||

| Factor | Model Coefficient (SE) |

Model 1 Coefficient (SE) |

Final Model Coefficient (SE) |

Model Coefficient (SE) |

Model 1 Coefficient (SE) |

Final Model Coefficient (SE) |

| Fixed effects | ||||||

| Intercept | 48.41 (0.78)*** | 60.12 (4.35)*** | 59.60 (3.57)*** | 49.83 (0.97)*** | 48.76 (4.56)*** | 45.98 (3.54)*** |

| Time (linear rate of change) | −0.12 (0.15) | −0.88 (0.42)* | −0.78 (0.36)* | −0.13 (0.17) | 0.38 (0.29) | 0.29 (0.22) |

| Intercept | ||||||

| Demographic and Clinical Covariates | ||||||

| Age | −0.19 (0.05)*** | −0.14 (0.04)** | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.11 (0.04)* | ||

| Gender (ref. male) | −3.96 (1.52)** | −2.27 (1.26) | −2.04 (1.36) | −0.29 (1.07) | ||

| Marital Status (ref. no) | 0.48 (1.38) | −0.64 (1.12) | 4.80 (1.45)** | 3.56 (1.13)** | ||

| Ethnicity (ref. Hispanic) | −4.07 (1.39)** | −4.06 (1.12)*** | 2.12 (1.47) | 2.28 (1.15)* | ||

| Transplant Risk Status (ref. low) | ||||||

| High/Very High | −0.38 (1.56) | 0.63 (1.28) | −3.39 (1.69)* | −2.55 (1.31) | ||

| Intermediate | 2.09 (1.59) | 2.42 (1.28) | −1.47 (1.68) | −0.69 (1.30) | ||

| HCT-CI (ref. 0) | ||||||

| >=3 Score | −2.59 (1.49) | −2.00 (1.21) | 2.44 (2.15) | 2.81 (1.60) | ||

| 1 or 2 Score | −1.40 (1.56) | −1.30 (1.26) | 6.28 (2.30)** | 4.87 (1.73)** | ||

| Conditioning Type (ref. RIC) | 0.60 (1.41) | 0.38 (1.16) | −2.78 (1.51) | −2.47 (1.19)* | ||

| Time Varying Predictors | ||||||

| Evidence of Disease1 (ref. none) | −1.45 (0.85) | |||||

| Immune Suppression (ref. none) | −2.85 (0.79)*** | |||||

| Physical Symptom Distress | −0.47 (0.06)*** | −0.62 (0.05)*** | ||||

| Linear (interaction) | ||||||

| Gender by Time | 0.59 (0.29)* | 0.47 (0.25) | ||||

| Physical Symptom Distress by Time | 0.03 (0.01)* | |||||

| Variance components | ||||||

| Within-person | 20.87 (1.76)*** | 21.27 (1.79)*** | 20.50 (1.50)*** | 33.98 (2.76)*** | 33.54 (2.69)*** | 30.11 (2.20)*** |

| In intercept | 62.80 (10.99)*** | 49.79 (9.69)*** | 27.16 (6.10)*** | 95.50 (17.13)*** | 75.07 (15.02)*** | 31.10 (7.53)*** |

| In linear rate | 0.69 (0.39)* | 0.37 (0.33) | 0 | 1.11 (0.54)* | 0.83 (0.44)* | 0 |

| Covariance | −0.22 (1.72) | −0.22 (1.55) | 0.88 (0.76) | −6.20 (2.87)* | −4.84 (2.51) | −0.03 (0.81) |

| Goodness-of-fit deviance | 3652.2 | 3587.9 | 3472.7 | 3850.9 | 3783.3 | 3638.1 |

| Model comparison (χ2 [df]) | 64.3 (10) | 179.5 (14)*** | 67.6 (11) | 212.8 (12)*** | ||

| R2 at intercept | 20.7% | 56.8% | 21.4% | 67.4% | ||

| R2 at linear rate | 46.4% | 100% | 25.2% | 100% | ||

Abbreviations: PCS, Physical Component Score; MCS, Mental Component Score; SD, standard deviation; HSCT, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; HCT-CI, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation – comorbidity index.

NOTE:

Of those classified as having evidence of disease, 5 (14.7%) had achieved a CR but were continuing a course of disease specific treatment.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Physical Symptom Distress was centered on the 3 year mean of 34.04 and age was centered on the 3 year mean of 43.95. Intercept here means 3 years post HSCT. Education was not significant in the unconditional model.

Figure 1. Trajectories of Predicted PCS Scores1.

Abbreviations: PCS, Physical Component Score; HSCT, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

NOTE: 1RSCL physical symptom distress level was classified based on linearly transformed scores across 553 observations: High: n=261, Low: n=189.

Table 5.

Adjusted Means for PCS, MCS, and FACT-G

| Adjusted Means |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | PCS | MCS | FACT-G |

| Physical Symptom Distress1 | |||

| High | 43.7 (5.5) | 44.2 (5.7) | 78.1 (8.4) |

| Med | 49.2 (3.2) | 51.7 (3.1) | 89.5 (2.1) |

| Low | 53.2 (4.0) | 54.6 (3.7) | 95.5 (3.5) |

| Occurrence of Immunosuppression | |||

| No | 50.0 (5.4) | ||

| Yes | 46.0 (6.1) | ||

| Age | |||

| Older (>55) | 45.2 (5.6) | 52.9 (6.7) | |

| Younger (< 30) | 54.7 (4.9) | 50.1 (4.0) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 50.8 (5.5) | 51.0 (6.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 46.2(5.7) | 47.6 (5.6) | |

| Transplant Type | |||

| RIC | 51.2 (6.7) | ||

| Myeloablative | 47.3 (5.4) | ||

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 50.5 (6.1) | ||

| Non-married | 47.3 (6.6) | ||

| Comorbidity Index Score | |||

| 0 | 47.5 (7.2) | ||

| 1–2 | 54.2 (3.5) | ||

| >3 | 48.1 (6.0) | ||

Abbreviations: PCS, Physical Component Score; MCS, Mental Component Score; FACT-G, Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy-General; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning.

NOTE:

theoretical range 0–100; a score of < 10 was considered “low” (e.g. healthy population), 10 – 15 as “mild/moderate” (i.e. disease free population; newly diagnosed), and >15 as “high” (i.e. active treatment; high burden cancer type).

Mental Health

The unconditional model revealed there was no significant change in the mean trajectory of mental health (p ≥ 0.05) although the variance components were significant (table 3). In the final model (model 2), three time-varying predictors (evidence of disease, immunosuppression, physical symptom distress) explained additional variability in baseline mental health and the rate of change. After controlling for demographic and clinical covariates, greater symptom distress at any point following HSCT predicted significantly lower mental health (B=−0.62; p < 0.001). Overall, survivors with high symptom distress experienced clinically meaningful impairments in mental health (table 5).

Health Related Quality of Life

The unconditional model showed that there was no significant change in HRQL (p ≥ 0.05) although the variance components were significant (table 4). In the final model (model 2), three predictors (evidence of disease, immunosuppression, symptom distress) explained additional variability in baseline HRQL and the rate of change. After controlling for baseline demographic and clinical covariates, physical symptom distress at any point post-transplant predicted impairments in HRQL. Although HRQL scores were lower for survivors with greater physical symptom distress, scores were within the range for the healthy population suggesting no clinically meaningful impact from HSCT (table 5).

Table 4.

Final Hierarchical Linear Model for FACT-G

| FACT-G |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional | Conditional | ||

| Factor | Model Coefficient (SE) |

Model 1 Model 1 |

Final Model Coefficient (SE) |

| Fixed effects | |||

| Intercept | 87.65 (1.39)*** | 95.61 (7.80)*** | 89.87 (5.48)*** |

| Time (linear rate of change) | −0.39 (0.25) | −1.00 (0.41)* | −0.20 (0.31) |

| Intercept | |||

| Demographic and Clinical Covariates | |||

| Age | −0.13 (0.10) | −0.02 (0.07) | |

| Gender (ref. male) | −3.01 (2.36) | 0.09 (1.65) | |

| Marital Status (ref. no) | 2.19 (3.00) | 2.38 (2.21) | |

| Ethnicity (ref. Hispanic) | −0.92 (2.53) | −0.89 (1.75) | |

| Transplant Risk Status (ref. low) | |||

| High/Very High | −4.71 (2.88) | −2.43 (2.03) | |

| Intermediate | −1.53 (2.91) | −0.57 (2.02) | |

| HCT-CI (ref. 0) | |||

| >=3 Score | 0.19 (2.74) | 0.86 (1.91) | |

| 1 or 2 Score | 3.47 (2.85) | 3.75 (1.98) | |

| Conditioning Type (ref. RIC) | −2.25 (2.57) | −2.27 (1.81) | |

| Time Varying Predictors | |||

| Evidence of Disease1 (ref. none) | −1.09 (1.22) | ||

| Immune Suppression (ref. none) | −1.23 (1.18) | ||

| Physical Symptom Distress | −1.03 (0.06)*** | ||

| Variance components | |||

| Within-person | 48.99 (4.07)*** | 48.63 (4.03)*** | 37.05(3.12)*** |

| In intercept | 221.56 (35.44)*** | 203.99 (34.59)*** | 100.03 (19.08)*** |

| In linear rate | 2.44 (1.05)** | 2.17 (1.04)* | 0.55 (0.61) |

| Covariance | −9.29 (5.66) | −7.84 (5.68) | −3.43 (3.13) |

| Goodness-of-fit deviance | 4180.3 | 4141.4 | 3881.4 |

| Model comparison (χ2 [df]) | 38.9 (10) | 298.9 (13)*** | |

| R2 at intercept | 7.9% | 54.9% | |

| R2 at linear rate | 11.1% | 77.5% | |

Abbreviations: FACT-G, Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy-General; SD, standard deviation; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; HCT-CI, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation – comorbidity index; SE, standard error; HSCT, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

NOTE:

Of those classified as having evidence of disease, 5 (14.7%) had achieved a CR but were continuing a course of disease specific treatment.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Physical Symptom Distress was centered on the intercept mean of 34.04 and age was centered on the intercept mean of 43.95. Intercept here means 3 years post HSCT. Education was not significant in the unconditional model.

Symptom Experience

Since physical symptom distress was found to be a significant predictor for all three outcomes, further descriptive analyses were conducted. The mean PDS score for this sample was high (> 15) across the post-transplant study interval (table 2). Seventy-three (42.7%) subjects reported high levels of symptoms distress (> 15), while 37 subjects (21.6%) reported a moderate level of distress, and 61 subjects (35.7%) had low distress. Across time, the mean number of prevalent symptoms ranged from 8 symptoms (SD±5) to 10 symptoms (SD±6.6). Physical symptoms that were prevalent in a majority of subjects at almost every post-transplant year included: tiredness and lack of energy, sore muscles, low back pain, difficulty sleeping, decreased sexual activity, and difficulty concentrating. In the subgroup of participants with high symptom distress, additional symptoms that were prevalent in a majority of respondents included: headaches, dyspepsia, tingling hands or feet, hair loss, burning or sore eyes, shortness of breath, and dry mouth. The high symptom distress subgroup reported a mean number of prevalent symptoms that ranged across time from 12 (SD±3) symptoms to 14 (SD±4) symptoms.

Discussion

This study reveals that three or more years following HSCT, physical health, mental health and HRQL have generally recovered to normative values and that these trajectories remain stable. This observation that self-assessed health status and HRQL are preserved three or more years post-transplant supports previous studies suggesting that a full recovery is likely by three years post-transplant [39]. The novel insight provided by this study is that the trajectory remains stable, suggesting that treatment with allogeneic HSCT, while expensive, potentially risky, and burdensome, has the potential to return survivors to a health state that is comparable to healthy population values.

Although a majority of HSCT survivors are likely to achieve a satisfactory recovery in terms of health status and HRQL, it has been argued previously that “complacency is not an option” [40]. Substantial variability in health status and HRQL existed among survivors, for which physical symptom distress was a significant predictor. Respondents with higher symptom distress reported a physical and mental health status that was significantly lower than healthy population values, and this difference was also clinically meaningfully. Moreover, in survivors with high symptom distress, the trajectory of physical health reflected impairment through and beyond the first decade post-transplant. These findings support systematic screening of health status to identify HSCT survivors at risk for long term impairments.

These findings suggest that symptom distress, as a symptomatic late effect of HSCT, is an important target for clinical intervention. Other investigators have noted the importance of post-transplant symptom distress in accounting for impairments in a range of outcomes [41–44]. Although the nature of the symptoms described by survivors in the current study (fatigue, limited sexual interest, difficulty sleeping and difficulty concentrating) have been well documented [45], this study is the first to characterize the contribution that symptom distress makes to clinically significant impairments in health status and HRQL in transplant survivors over time. Factors that may contribute to symptom distress in allogeneic HSCT survivors include post-transplant comorbid conditions, late treatment effects, cGvHD, and side effects of immunosuppression [15]. Consistent with findings from previous studies [16, 17], treatment with immunosuppression also predicted significant impairments in physical health for survivors. The findings from the present study suggest that subgroups of transplant recipients, including those experiencing higher symptom burden and those receiving treatment for cGvHD, are coping with significant impairments, suggesting a need for aggressive supportive care management. Additional studies to more fully characterize both the symptom experience and its underlying causal pathways are needed to inform the development of tailored supportive care interventions for transplant survivors.

In addition, survivors who were older and non-Hispanic reported significantly lower levels of physical health. These results are consistent with the findings of another investigator who also observed that these two demographic factors were associated with limitations in physical health post-transplant [16]. The association between ethnicity and physical health is somewhat in contrast to other studies that have described an association between individuals of Hispanic ethnicity and inferior HSCT outcomes [46, 47]. It should be noted that a majority of Hispanic participants in the current study were residing outside the U.S. This factor may have biased our sample towards Hispanic respondents with a level of social support or financial resources that facilitated their travel to the U.S. for the HSCT. In addition, the return to an ethnically homogeneous community during post-transplant reintegration might produce salutary effects on aspects of self-assessed health for long-term survivors [48, 49]. The observed association between being Hispanic and more favorable physical health should be explored in future studies using samples that are sufficiently large to permit subgroup analysis.

Relative to mental health, survivors who were younger, unmarried, non-Hispanic, received an RIC and who proceeded into HSCT without comorbidities, reported less favorable mental health. Although these predictors achieved statistical significance in the model, their clinical relevance is uncertain. Except for physical symptom distress, between-group differences in adjusted means for mental health based on age, marital status, race/ethnicity, transplant conditioning, and comorbidity did not exceed the minimally important difference of three points (table 5).

These study results should be interpreted in light of several limitations including that we were underpowered for a variety of subgroup analyses. Further, the inclusion of post-transplant comorbidity as a time-varying covariate might have refined our understanding of the factors that predict variation in transplant recovery. We gauged the presence and severity of cGvHD by scoring the intensity of immunosuppression rather than clinical grading of cGvHD, since such grading was not consistently available for all subjects at all time points. Notably, intensity of immunosuppression was a significant predictor of impairment in physical health, but not mental health or HRQL. Future studies should make every effort to incorporate objective clinical grading of cGVHD using the NIH Criteria [50], in addition to measurement of intensity of immunosuppression. We also cannot exclude a possibility that response shift explains some of the findings observed in this study. When response shift occurs, respondents change their internal standards, values, and conceptualizations of HRQL over time as part of their accommodation to the long-term physical consequences of serious chronic or life-threatening illness [51]. Thus, as a result of response shift, respondents may rate their health status or quality of life as satisfactory despite objective evidence of adverse clinical changes [52–54]. There has been only limited study of response shift in cancer survivors more generally, and future research is needed to determine whether this phenomenon accounts for some of the observed effects in HRQL studies in allogeneic HSCT survivors. At the same time, the strengths of our study include the focus on allogeneic HSCT recipients, rather than a mixed sample of allogeneic and autologous recipients. Other strengths include the longitudinal design, inclusion of an ethnically and linguistically diverse sample, the control of important biomedical covariates, limited sample attrition, and the inclusion of transplant survivors with evidence of disease recurrence, a group that has to date, been understudied.

Clinically, our results underscore the importance of aggressive symptom management in optimizing health outcomes in long term survivors; those receiving more intensive immunosuppression are an important subgroup to target for interventions. Careful monitoring of symptom distress and its impact on daily functioning is an important supplement to HRQL measurement. One might argue that symptom distress is not reliably assessed by providers [55], supporting the importance of incorporating patient-reported outcomes into routine practice. Lastly, the flat trajectory in health status and HRQL post-transplant suggests both an opportunity and a risk for individuals facing allogeneic HSCT. Additional studies are needed to define factors that contribute to physical symptom distress post-transplant, and to test interventions that can favorably redirect the trajectory of post-transplant recovery for those at risk for adverse outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephen Klagholz, BS; Heather Gelhorn, PhD; Chris Thompson, BA; Olena Prachenko, MA; Lisa Cook, RN, MSN; Eleftheria (Libby) Koklanaris, RN, BSN, OCN®; Bipin Savani, MD; Karen Soeken, PhD; Catalina Ramos, RN; Bazetta Blacklock Schuver, RN, BSN; Gwenyth Wallen, RN, PhD; NCI and NHBLI Intramural Research Transplant Teams; NIH Clinical Center staff; and research participants.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the NIH Clinical Center Intramural Research Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors’ Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Margaret F. Bevans, Email: mbevans@cc.nih.gov.

Sandra A. Mitchell, Email: mitchlls@mail.nih.gov.

John Barrett, Email: barrettj@nih.gov.

Michael R. Bishop, Email: mbishop@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu.

Richard Childs, Email: childsr@mail.nih.gov.

Daniel Fowler, Email: df15v@mail.nih.gov.

Michael Krumlauf, Email: krumlaum@mail.nih.gov.

Patricia Prince, Email: pprince@cc.nih.gov.

Nonniekaye Shelburne, Email: nonniekaye.shelburne@nih.gov.

Leslie Wehrlen, Email: lwehrlen@nih.gov.

Li Yang, Email: li.yang@nih.gov.

References

- 1.Appelbaum FR. The current status of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:491–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gratwohl A, Passweg J, Baldomero H, Urbano-Ispizua A. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation activity in Europe 1999. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:899–916. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Marrow Donor Program. Unrelated Search & Transplant - Trends in Allogeneic Transplants. National Marrow Donor Program. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn T, McCarthy PL, Jr, Hassebroek A, et al. Significant Improvement in Survival After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation During a Period of Significantly Increased Use, Older Recipient Age, Use of Unrelated Donors. J Clin Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Lee SJ, et al. Recommended screening and preventive practices for long-term survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:337–341. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: A conceptual model of patient outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosher CE, Redd WH, Rini CM, Burkhalter JE, DuHamel KN. Physical, psychological, and social sequelae following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review of the literature. Psycho-Oncol. 2009;18:113–127. doi: 10.1002/pon.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pidala J, Anasetti C, Jim H. Quality of life after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;114:7–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-182592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norkin M, Hsu JW, Wingard JR. Quality of life, social challenges, and psychosocial support for long-term survivors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Semin Hematol. 2012;49:104–109. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agra Y, Badia X. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist to assess quality of life of cancer patients. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 1999;73:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belec RH. Quality of life: perceptions of long-term survivors of bone marrow transplantation. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1992;19:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molassiotis A, Van Den Akker OBA, Milligan DW, et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors of marrow transplantation: Comparison with a matched group receiving maintenance chemotherapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redaelli A, Stephens JM, Brandt S, Botteman MF, Pashos CL. Short- and long-term effects of acute myeloid leukemia on patient health-related quality of life. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30:103–117. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(03)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bevans M. Health-related quality of life following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:248–254. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khera N, Storer B, Flowers ME, et al. Nonmalignant late effects and compromised functional status in survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:71–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wingard JR, Huang IC, Sobocinski KA, et al. Factors associated with self-reported physical and mental health after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:1682–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell SA, Leidy NK, Mooney KH, et al. Determinants of functional performance in long-term survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:762–769. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bevans MF, Mitchell SA, Barrett AJ, et al. Function, adjustment, quality of life and symptoms (FAQS) in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) survivors: a study protocol. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrett AJ, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, et al. Marrow transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Factors affecting relapse and survival. Blood. 1989;74:862–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bishop MR, Hou JWS, Wilson WH, et al. Establishment of early donor engraftment after reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to potentiate the graft-versus-lymphoma effect against refractory lymphomas. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:162–169. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Childs RW, Clave E, Tisdale J, Plante M, Hensel N, Barrett J. Successful treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma with a nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral-blood progenitor-cell transplant: evidence for a graft-versus-tumor effect. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2044–2049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fowler DH, Mossoba ME, Steinberg SM, et al. Phase 2 clinical trial of rapamycin-resistant donor CD4+ Th2/Th1 (T-Rapa) cells after low-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2013;121:2864–2874. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-446872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B, Maruish ME. User's manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. Licoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arocho R, McMillan CA. Discriminant and Criterion Validation of the US-Spanish Version of the SF-36 Health Survey in a Cuban-American Population with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Med Care. 1998;36:766–772. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arocho R, McMillan CA, Sutton-Wallace P. Construct validation of the USA-Spanish version of the SF-36 health survey in a Cuban-American population with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:121–126. doi: 10.1023/a:1008801308886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayuso-Mateos JL, Lasa L, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Oviedo A, Diez M. Measuring health status in psychiatric community surveys: Internal and external validity of the Spanish version of the SF-36. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb05381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peek MK, Ray L, Patel K, Stoebner-May D, Ottenbacher KJ. Reliability and validity of the SF-36 among older Mexican Americans. Gerontologist. 2004;44:418–425. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J, Webster K, Cella D. General population and cancer patient norms for the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G) Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:192–211. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cella D, Hernandez L, Bonomi AE, et al. Spanish language translation and initial validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy quality-of-life instrument. Med Care. 1998;36:1407–1418. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199809000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dapueto JJ, Francolino C, Servente L, et al. Evaluation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) Spanish version 4 in South America: Classic psychometric and item response theory analyses. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Haes JC, Olschewski M, Fayers P. Measuring the quality of cancer patients with Rotterdam Symptom Checklist: a manual. Groningen: Northern Center for Health Research; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armand P, Gibson CJ, Cutler C, et al. A disease risk index for patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;120:905–913. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-418202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorror ML. How I assess comorbidities before hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2013;121:2854–2863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-455063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baird K, Steinberg SM, Grkovic L, et al. National Institutes of Health chronic graft-versus-host disease staging in severely affected patients: organ and global scoring correlate with established indicators of disease severity and prognosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fassil H, Bassim CW, Mays J, et al. Oral Chronic Graft-vs.-Host Disease Characterization Using the NIH Scale. J Dent Res. 2012;91:S45–S51. doi: 10.1177/0022034512450881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mo XD, Xu LP, Liu DH, et al. Health related quality of life among patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:3048–3052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singer J, Willett J. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.SAS. SAS System for Windows. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, et al. Recovery and long-term function after hematopoietic cell transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma. JAMA. 2004;291:2335–2343. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bevans MF. Complacency is not an option. Blood. 2011;118:4506–4507. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-373332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bevans MF, Mitchell SA, Marden S. The symptom experience in the first 100 days following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1243–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0420-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daikeler T, Mauramo M, Rovo A, et al. Sicca symptoms and their impact on quality of life among very long-term survivors after hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013 doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pallua S, Giesinger J, Oberguggenberger A, et al. Impact of GvHD on quality of life in long-term survivors of haematopoietic transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1534–1539. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Syrjala KL, Yi JC, Artherholt SB, Stover AC, Abrams JR. Measuring musculoskeletal symptoms in cancer survivors who receive hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:225–235. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0126-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Syrjala KL, Martin PJ, Lee SJ. Delivering care to long-term adult survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3746–3751. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baker KS, Loberiza FR, Jr, Yu H, et al. Outcome of ethnic minorities with acute or chronic leukemia treated with hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7032–7042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serna DS, Lee SJ, Zhang MJ, et al. Trends in survival rates after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for acute and chronic leukemia by ethnicity in the United States and Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3754–3760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aranda MP, Ray LA, Snih SA, Ottenbacher KJ, Markides KS. The protective effect of neighborhood composition on increasing frailty among older Mexican Americans: a barrio advantage? J Aging Health. 2011;23:1189–1217. doi: 10.1177/0898264311421961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quintella Mendes GL, Koifman S. Socioeconomic status as a predictor of melanoma survival in a series of 1083 cases from Brazil: just a marker of health services accessibility? Melanoma Res. 2013;23:199–205. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32835e76f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2005;11:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sprangers MAG, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1507–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gandhi PK, Ried LD, Huang IC, Kimberlin CL, Kauf TL. Assessment of response shift using two structural equation modeling techniques. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:461–471. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rapkin BD, Schwartz CE. Toward a theoretical model of quality-of-life appraisal: Implications of findings from studies of response shift. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Visser MRM, Oort FJ, van Lanschot JJB, et al. The role of recalibration response shift in explaining bodily pain in cancer patients undergoing invasive surgery: an empirical investigation of the Sprangers and Schwartz model. Psycho-Oncol. 2013;22:515–522. doi: 10.1002/pon.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiao C, Polomano R, Bruner DW. Comparison Between Patient-Reported and Clinician- Observed Symptoms in Oncology. Cancer Nurs. 2012 doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318269040f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]