Abstract

A lady had suffered from deep infection of the GSB III prosthesis of her right elbow. The infection could not be controlled by repeated debridement. Finally, cemented arthrodesis was performed and the infection was eradicated.

Background

Elbow joints are often involved in rheumatoid arthritis. The surgical treatment choice for the rheumatoid elbow depends on the severity of joint destruction. Total elbow arthroplasty is indicated in high grade of joint destruction.1 It is a promising surgical method for decreasing pain and instability and for restoring range of motions of the affected elbow joints.2 The designs of total elbow arthroplasty can be classified into linked and unlinked types. The linked type can be further subdivided into fully constrained hinge or semiconstrained hinge designs.2 While the initial fixed bearing implants tended to progress to early loosening, the development of the so-called ‘sloppy joints’ has seen a major advance in the survival and success rate of this arthroplasty.3 The sloppy hinges have a clearance between both components, permitting movement in the sagittal plane and in the frontal plane and also some rotation. Sloppy hinges with condylar configurations as the GSB III elbow prosthesis further reduce the stresses on the interface and have better long-term results.4 In cases with rheumatoid arthritis the survival rate of GSB III at 10 years reaches 90%.2 4 5 However, the complication rate of aseptic loosening, infection, instability and nerve lesions is still definitely larger than with hip, knee and shoulder prostheses.4 We presented a case of infected GSB III prosthesis that was successfully treated by cemented arthrodesis.

Case presentation

An 83-year- old woman had suffered from rheumatoid arthritis with bilateral total knee arthroplasty, bilateral total elbow arthroplasty and right total hip arthroplasty. The right total elbow arthroplasty was performed in 2002. She was wheelchair user and was cared for by her daughter and a maid. She was admitted to our department because of the development of two ulcers over her right elbow 3 weeks before admission. The ulcers were progressively increasing in size, painful and with pustule and blood-stained discharge. She did not have any fever. There was no definite preceding injury to her right elbow although the patient had repeatedly scratched that area due to itchiness.

Clinically, there was 30° of flexion contracture of her right elbow with moderately swollen and erythematous elbow joint. There were two ulcers at the posteromedial and posterolateral aspects of the joint, which were covered by granulation tissue with blood stained and pustule discharge.

Radiographs of her right elbow showed a Gschwend, Scheier, Baehler (GSB) III total elbow arthroplasty in situ. There was no bony erosion or any loosening of the prosthesis. Debridement of the ulcers and elbow arthrotomy was performed. The flanges of the humeral component of the GSB III were exposed after debridement of the granulation tissue of the ulcers (figure 1). There was an infected granulation tissue in the elbow with turbid joint fluid. The anterior soft tissue was stripped from the distal humerus in order to correct the flexion contracture. This relieved the soft tissue tension of the posterior part of the elbow and allowed closure of the ulcers. Postoperatively, the elbow was protected with an extension splint. Culture of the granulation tissue yielded Staphylococcus aureus which was sensitive to cloxacillin, methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA). She was treated with intravenous cloxacillin 1 g every 6 h. The wounds healed up but the posteromedial ulcer recurred 1 month later. She also reported recurrence of elbow pain. Wound swab yielded MSSA. Another arthrotomy and debridement of her right elbow was performed. The wounds healed but the ulcer recurred 1 month later with pus discharge (figure 2).

Figure 1.

(A) Ulcers at the posteromedial and posterolateral corner of the elbow. (B and C) Radiographs of the elbow showing the prosthesis was well fixed and there was no apparent osseous involvement. (D) After debridement of the granulation tissue of the ulcers, the flanges of the prosthesis were exposed.

Figure 2.

(A and B) Recurrence of posteromedial ulcer with discharge.

Treatment

The plan of management was adequate debridement and cemented arthrodesis to provide an antibiotic impregnated spacer that would allow the elbow to rest in an extended position. The patient was monitored clinically, radiologically and biochemically to see whether the infection was under control or not. Removal of the cement would be considered later if the patient wanted to restore a mobile elbow joint. If the infection was not controlled, removal of the prosthesis with/without later revision or even amputation would be considered.

Technique

The patient was put in supine position and no pneumatic tourniquet was applied. Arthrotomy of the elbow was performed through the previous posterior surgical scar. The prosthesis was uncoupled so that the anterior compartment of the elbow could be assessed. The joint and the sinus tract were thoroughly debrided and irrigated with hydrogen peroxide, aqueous hibitane and normal saline. The anterior compartment of the elbow was packed with gentamycin impregnated cement. The elbow prosthesis was then coupled before the cement hardened and the elbow was extended. The anterior cement would be pressed towards the prosthesis and the bones by the tension of the anterior soft tissue. The anterior part of the cement can provide a better splinting support to keep the elbow in extension. The posterior compartment was then packed with the gentamycin impregnated cement with the elbow extended (figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Intraoperative photos during cemented arthrodesis. (A) The prosthesis was surrounded by infected granulation tissue. (B) The prosthesis was uncoupled for debridement of the anterior elbow. (C) Cemented arthrodesis with the elbow extended.

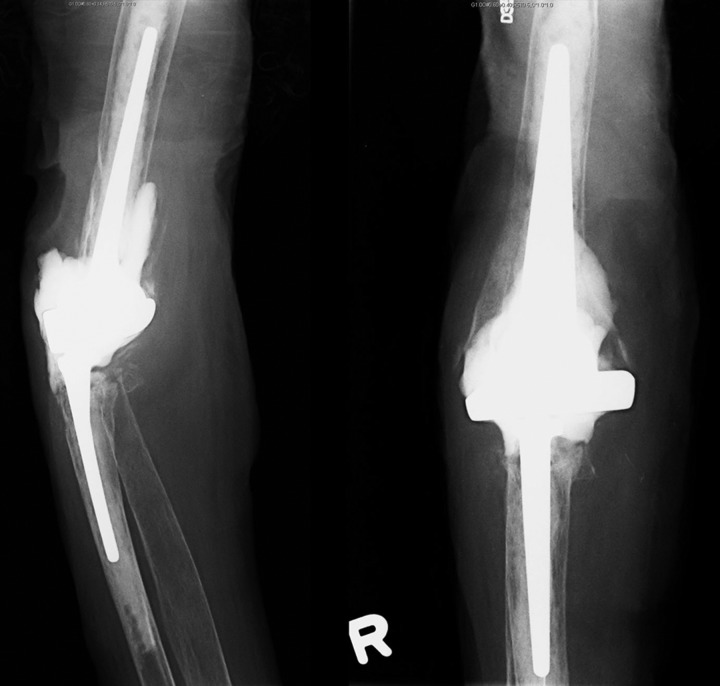

Figure 4.

Radiographs of the right elbow after cemented arthrodesis.

Outcome and follow-up

The wounds healed up and the antibiotics were stopped 6 weeks after the operation. On the latest follow-up, 13 months after the operation, there was no recurrence of infection. The patient was satisfied about the result and refused removal of the cement.

Discussion

The cause of deep infection of the GSB III prosthesis in this case was likely to be multifactorial. The patient had rheumatoid arthritis are likely to be immunocompromised.6 The GSB III is a floppy hinge with flanges on the lower and anterior part of the distal humerus.7 The edges of the flanges can impinge onto the wasted triceps and anconeus muscles and the thin skin and cause posterolateral and posteromedial ulceration in case of flexion contracture of the elbow.

The surgical treatment choices of an infected total elbow arthroplasty include component retention surgery with irrigation and debridement, removal of the components and creation of a resection arthroplasty or staged revision surgery.8 Antibiotic suppression and amputation have an important but limited role in the management of an infected arthroplasty.

An increased awareness of deep infection of the prosthesis has led to a high index of suspicion and earlier recognition. Often, patients are now seen while the infection is still acute, the components are well fixed. Removal of the prosthesis in these circumstances may necessitate extensive destruction of the bone, obviating a possible exchange arthroplasty or even a fracture of the humerus or ulna.9

The primary indication for retention of the prosthesis is a short (less than 30-day) interval from the onset of symptoms to treatment and the prosthesis is well fixed and there is no apparent osseous involvement as determined radiographically and intraoperative.9 In order to salvage the prosthesis, multiple extensive irrigation and debridement procedures are needed.9

However, the success rate of eradication of infection and salvage of the prosthesis was about 50% and repeated operations necessary to retain a prosthesis may not be optimal in medically frail patients.9

We adopted the approach of repeated debridement initially because the prosthesis was well fixed in this case. We preformed anterior soft tissue release to correct the flexion contracture in order to relief the posterior soft tissue impingement by the flanges. However, the infection could not be controlled. Because of the poor quality and quantity of the bones, removal of the prosthesis would be a major surgical undertaking in this patient and high chance of complications was expected. Therefore, removal of the prosthesis with or without staged revision was reserved and cement arthrodesis was performed instead. This procedure was a relatively simple and safe procedure. It provided an internal splintage to keep the elbow in an extended position and relieve the soft tissue tension of the posterior elbow. It filled up the dead space and delivered a local high concentration of antibiotics. This procedure is reversible by removal of the cement spacer and does not affect subsequent surgical options including resection arthroplasty, staged revision or amputation. However, we are not sure of the long-term result of the procedure. Retention of the cement as in this case may increase the risk of periprosthetic fracture as the joint was ankylosed. Moreover, the cement space may break and flexion deformity may recur and lead to recurrence of posterior elbow ulcer. On the other hand, we are not sure of the best time for removal of the cement spacer if conversion to a mobile joint is planned and whether the infection will recur or not after the conversion.

Learning points.

Deep infection of total elbow prosthesis is difficult to treat.

Salvage of the prosthesis is possible if the prosthesis is well fixed and there is no apparent osseous involvement.

Cemented arthrodesis is a feasible approach to retain the prosthesis.

Footnotes

Contributors: THL is responsible for collection of the clinical data, literature review and preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Jensen CH, Jacobsen S, Ratchke Met al. The GSB III elbow prosthesis in rheumatoid arthritis: a 2- to 9-year follow-up. Acta Orthop 2006;77:143–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishii K, Mochida Y, Harigane K, et al. Clinical and radiological results of GSB III total elbow arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2012;22:223–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loehr JF, Gschwend N, Simmen BR, et al. Endoprosthetic surgery of the elbow. Orthopade 2003;32:717–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gschwend N. Present state-of-the-art in elbow arthroplasty. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica 2002;68:100–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gschwend N, Scheier NH, Baehler AR. Long-term results of the GSB III elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg 1999;81B:1005–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly EW, Coghlan J, Bell S. Five- to thirteen-year follow-up of the GSB III total elbow arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2004;13:434–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gschwend N, Simmen BR, Matejovsky Z. Late complications in elbow arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1996;5:86–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peach CA, Nicoletti S, Lawrence TM, et al. Two-stage revision for the treatment of the infected total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg 2013;95B:1681–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamaguchi K, Adams RA, Morrey BF. Infection after total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg 1998;80:481–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]