Abstract

Salivary glands, a major component of the mucosal immune system, confer antigen-specific immunity to mucosally acquired pathogens. We investigated whether a physiological route of inoculation and a subunit vaccine approach elicited MCMV-specific and protective immunity. Mice were inoculated by retrograde perfusion of the submandibular salivary glands via Wharton's duct with tcMCMV or MCMV proteins focused to the salivary gland via replication-deficient adenovirus expressing individual MCMV genes (gB, gH, IE1; controls: saline and replication deficient adenovirus without MCMV inserts). Mice were evaluated for MCMV-specific antibodies, T-cell responses, germinal center formation, and protection against a lethal MCMV challenge. Retrograde perfusion with tcMCMV or adenovirus expressed MCMV proteins induced a 2- to 6-fold increase in systemic and mucosal MCMV-specific antibodies, a 3- to 6-fold increase in GC marker expression, and protection against a lethal systemic challenge, as evidenced by up to 80% increased survival, decreased splenic pathology, and decreased viral titers from 106 pfu to undetectable levels. Thus, a focused salivary gland immunization via a physiological route with a protein antigen induced systemic and mucosal protective immune responses. Therefore, salivary gland immunization can serve as an alternative mucosal route for administering vaccines, which is directly applicable for use in humans.—Liu, G., Zhang, F., Wang, R., London, L., London, S. D. Protective MCMV immunity by vaccination of the salivary gland via Wharton's duct: replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus expressing individual MCMV genes elicits protection similar to that of MCMV.

Keywords: inflammation, mucosal immunity, vaccine development

The salivary glands play an important role in host defense and are a major contributor to both the innate and adaptive host defense of the upper gastrointestinal tract, conferring antigen-specific immunity to oral and mucosally acquired pathogens (1–3). Because of the importance of salivary gland function in regard to oral health, a better understanding of the immunobiology of the salivary gland from the perspective of limiting immunopathologies and for the induction and maintenance of protective immune responses is necessary. Since mucosal surfaces of the body are a significant portal of entry for many pathogens, especially viruses, understanding the mechanisms of defense in these tissues is an important endeavor in vaccine development (1, 4–6). Mucosally administered vaccines are of interest not only because of their ease of administration and lack of discomfort, but also their ability to protect at multiple mucosal sites as well as systemic sites (7). Therefore, investigating methods for the induction of immune responses in the common mucosal immune system including the salivary gland is an important field of investigation and further characterizing inductive sites in this system will lead to advances in the development of vaccines for pathogens that impinge on mucosal surfaces.

We previously described a model of a focused salivary gland infection, which we used to investigate the hypothesis that the salivary gland acts as a mucosal inductive site, as well as its known function as an effector site in oral mucosal immunity (8, 9). We demonstrated that intraglandular inoculation with tissue culture-derived murine cytomegalovirus (tcMCMV), which is attenuated with respect to its ability to infect systemic tissues, limited infection to the salivary gland without high viral titers and pathology in other organs and stimulated a local host immune response (8, 9). This immunization protocol also induced salivary gland ectopic follicles that displayed both functional and phenotypic characteristics of mucosal inductive site germinal centers (GCs) including cognate interactions of B and T cells with follicular dendritic cells, proliferating cells, class switching, plasma cell differentiation, and protection against a lethal systemic challenge with MCMV (8, 9). This data provided direct evidence that the salivary glands can act as a mucosal inductive site, which may be dependent, at least in part, on lymphoid neogenesis within the salivary gland. In this study, we utilized the MCMV model to extend our proof of concept that salivary gland vaccination could be an important new clinical route for mucosal vaccines through the use of the novel vaccine strategy of retrograde perfusion of the submandibular salivary gland and the use of replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus expressing individual MCMV genes. This vaccine strategy led to the development of MCMV-specific T- and B-cell responses characterized by neutralizing MCMV-specific IgG and IgA antibodies in the serum and saliva, a CD8+ population specific for a major MCMV cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope derived from the IE1 gene, a 3- to 6-fold increase in GC marker expression, and protection against a lethal systemic challenge utilizing virulent salivary gland-derived MCMV. These results extend and broadens our previous finding that the salivary gland is an inductive site by demonstrating that immunization with replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus expressing individual MCMV genes, which serves as a model for a noninfectious, conventional vaccine, also induced ectopic GCs leading to MCMV-specific and protective immunity. Thus, these results directly demonstrate that salivary gland immunization via retrograde perfusion can serve as an alternative mucosal route for administering vaccines for the induction of protective mucosal immune response to pathogens that impinge on mucosal surfaces including viruses and bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus

Female CD1 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) were used to propagate MCMV in vivo. Smith strain MCMV [105 plaque-forming units (pfu)/mouse; American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA, USA) was injected i.p. into CD1 mice. After 14 d, salivary glands were homogenized using a BeadBeater (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK, USA) and titered for MCMV pfu via a standard plaque assay utilizing 3T12 cells (8). The homogenate was used to infect naive CD1 mice (105 pfu/mouse). This process was repeated twice, and third-passage MCMV was used for inoculation (referred to as MCMV). Attenuated tcMCMV was generated by infecting 3T12 mouse embryo fibroblasts (ATCC) with third-passage MCMV (MOI 0.1). After 6 d of culture, tcMCMV was isolated from the supernatant and infected fibroblasts as described previously (8) and purified using sucrose density gradient centrifugation (10). Recombinant adenoviruses expressing gB, gH, or IE1 of MCMV were constructed by inserting those genes into a replication-deficient adenovirus (Ad) vector and transfection into AD-293 cells to generate infectious virus (Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1; refs. 11, 12). The replication-deficient recombinant adenoviruses and FG140, the replication-deficient adenovirus lacking an insert, were amplified by 3 passages in AD-293 cells, tittered via a standard plaque assay utilizing AD-293 cells, and stored at −80°C until use. All recombinant adenoviruses, FG140, and the AD-193 cell line were kindly provided by Dr. John Shanley (University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA).

Salivary gland immunization via Wharton's duct

Supplemental Fig. S1A demonstrates the method of retrograde perfusion of the submandibular salivary gland via Wharton's duct (13). Female Balb/cByJ mice (5 to 6 wk old; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were subcutaneously injected with atropine sulfate monohydrate (0.5 mg/kg) to prevent salivary secretions and anesthetized i.p. with ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) in 0.9% saline. The mice were placed on a custom-made plastic platform in the ventral position. The maxillary incisors were locked on a metal wire, and the mandibular incisors were hooked on an elastic string to hold the mouth open (Supplemental Fig. S1B). A 0.58-mm-diameter polyethylene tube (PE-10; Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA, USA) was inserted 3–5 mm inside Wharton's duct, and an insulin syringe with a 29-gauge needle was inserted into the other end of the polyethylene tube (Supplemental Fig. S1B). Next, 100 μl (50 μl/duct) of immunogen was slowly injected into the submandibular salivary gland.

Animals

Female Balb/cByJ mice (5 to 6 wk old) were immunized with 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV in 60 mM sodium bicarbonate or the equivalent volume of saline via retrograde perfusion of the salivary gland. For prime-boost experiments, 21 d after primary immunization, mice were boosted with either 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV in 60 mM sodium bicarbonate or the equivalent volume of saline via retrograde perfusion. Prime-boost experiments were analyzed 10 d after boost. In protection studies, Balb/cByJ mice were challenged systemically (i.p.) with salivary gland-derived MCMV (100 μl containing 5×104 or 2×104 pfu/mouse, as indicated) on d 28 postinoculation. In experiments utilizing replication-deficient recombinant adenoviruses, Balb/cByJ mice were immunized and boosted on d 30 with 106 pfu/mouse replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus expressing MCMV gB, gH, IE1 or a combination of gB, gH, and IE1 (106 pfu/mouse of each recombinant virus). Mice immunized with 106 pfu/mouse FG140 or saline (mock treatment) served as negative controls. In protection studies, Balb/cByJ mice were challenged systemically (i.p.) with salivary gland-derived MCMV (100 μl containing 5×104 or 2×104 pfu/mouse, as indicated) on d 30 after boost immunization. In all protection experiments, body weight and survival were monitored daily after challenge. All animal protocols were approved by the Stony Brook University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Review Boards.

Collection of lymphocyte populations

Single-cell suspensions of salivary gland cells were obtained as described previously, with modifications (8). Briefly, salivary glands were separated from the periglandular lymph nodes (PGLNs, also called superficial cervical lymph nodes) and adipose and connective tissues, using a dissecting microscope. Salivary glands were minced into small fragments and incubated 3 times in digestion medium containing CaCl2 (100 mM), collagenase type IV (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and DNase type I (0.1 mg/ml; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) in RPMI 1640 + 5% newborn calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA, USA) for 20 min at 37°C with stirring. Salivary gland lymphocytes were isolated using a discontinuous Percoll gradient (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA) spun at 1800 rpm for 20 min at 20°C. Lymphocytes were collected at the interface between 44 and 67.5% Percoll. Spleens and PGLNs were homogenized by grinding between two frosted glass slides, and debris was removed by passing the homogenate through a nylon mesh. Cells were pelleted by spinning at 1200 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. RBCs were lysed in ammonium chloride/potassium bicarbonate/EDTA (ACK buffer) for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed twice with cold PBS. Live cells were counted via trypan blue dye exclusion.

Flow cytometric analysis of pentamer staining

Cells (106) were stained with H-2Ld YPHFMPTNL pentamer (specific to MCMV IE1; ProImmune, Inc., Sarasota, FL, USA) conjugated with R-PE for 10 min at room temperature, stained with cell surface markers, CD8 and CD19 (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) and resuspended in fix buffer (1% fetal calf serum, 2.5% formaldehyde in PBS). Pentamer analysis was determined on CD19− cells. Flow cytometry data were acquired on an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Accuri, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA). The absolute number of positive cells for each subpopulation was obtained by multiplying cell yields by the percentage positive.

Collection of saliva, serum, vaginal wash, and fecal samples

Saliva was stimulated via a subcutaneous injection of pilocarpine nitrate (5 mg/ml, 0.15 mg/30 μl; Sigma-Aldrich), and collected using a pipette into microcentrifuge tubes on ice. Saliva was collected for a total of 20 min. Whole blood was collected from the vascular bundle located at the rear of the jawbone using Goldenrod Lancets (MEDIpoint, Inc., Mineola, NY, USA) weekly or by cardiac puncture at the time of sacrifice. Blood was allowed to clot at room temperature. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, removed to new microcentrifuge tubes, and stored at −20°C until assay. Vaginal wash samples were collected by 2 cycles introducing and withdrawing 100 μl of PBS with proteinase inhibitor cocktail into the vaginal vault. To measure antibody in the GI tract, fecal pellets were collected, and 20% (w/v) suspensions in sterile PBS with proteinase inhibitor cocktail were prepared. After subsequent centrifugation of the fecal suspensions, the supernatants were stored at −20°C.

ELISA for MCMV-specific antibodies

A stable cell line A13 (gift from J. Shanley), which expressed MCMV gB, was cultured, harvested, and lysed to make the coating antigen to measure MCMV-specific antibodies for mice immunized with tcMCMV. For the recombinant adenovirus studies, tcMCMV was used to coat the ELISA plates. A standard sandwich ELISA protocol was followed with slight modifications (14). Briefly, 96-well plates were coated overnight with 0.1 μg/μl (5 μg/well) MCMV gB or 5 μg/ml tcMCMV in coating buffer (0.1 M Na2CO3 and 0.2% NaN3, pH 9.6) at room temperature. Wells were blocked with 5% BSA in coating buffer for 2 h at 37°C, and washed with PBST (PBS and 0.05% Tween-20). Samples (in duplicate) were added at a 1:10 dilution in assay diluent (0.15 M NaCl, 0.001 M EDTA, 0.05 M Tris-HCl, 0.05% Tween 20, and 0.1% BSA), incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and washed with PBS/Tween-20. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated isotype specific goat anti-mouse IgM, IgG, or IgA (1:5000, Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) was used to detect bound, specific antibodies in samples after incubation for 1h at 37°C. Following 3 washes, substrate solution [1:1 mixture of color reagent A (H2O2) and color reagent B (tetramethylbenzidine); R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA] was added for a 5 min incubation at room temperature prior to the addition of stop solution. Optical density was measured at 450 nm.

RT-PCR

Salivary glands were homogenized in the presence of TRI Reagent solution (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Using a Qiagen OneStep RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 100 ng of total RNA for each reaction was used to amplify target genes with the following primer sets: gB, forward GAGATCATGCTGGGCACCTT, reverse CTCCAGACTGGTCACGTTCC; gH, forward TTCGGAGACGTGAGAGAGGT, reverse CAGGAACACCACATCGGTGA, IE1, forward AGTCTGGAACCGAAACCGTC, reverse GGACAACAGAACGCTCCTCA; β-actin, forward TTGTAACCAACTGGGACGATATGG, reverse GATCTTGATCTTCATGGTGCTAGG; activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), forward GGCTGAGGTTAGGGTTCCATCTCAG, reverse GAGGGAGTCAAGAAAGTCACGCTGGA; paired box protein 5 (PAX5), forward AGAGAAAAATTACCCGACTCCTC, reverse CATCCCTCTTGCGTTTGTTGGTG; and IμCα, forward CTCTGGCCCTGCTTATTGTTG, reverse GAGCTGGTGGGAGTGTCAGTG. The sizes of the amplification products were verified via 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. For semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis, band intensities on scanned gels were reported as densitometric data of the ratio of mock/average mock (controls) and the ratio of tcMCMV or individual MCMV genes (experimental)/average mock. Band intensities on scanned gels were analyzed using the Kodak Molecular Imaging Software on the Kodak Gel Logic 2200 Imaging system (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining

Salivary glands were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) immediately after harvest, placed in liquid nitrogen for 30 s, and stored at −80°C until sectioning. Frozen sections (7 μm) were dried briefly at room temperature, then fixed in acetone at −20°C. Slides were blocked for 1 h at room temperature using PBS with 1% BSA, then stained with monoclonal antibodies to MCMV gB (M55.01) and IE1 (IE1.01) (Dr. Stipan Jonjic, University of Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia) and gH (4B6:2; gift from J. Shanley) at room temperature for 1 h. Slides were then stained with goat anti-mouse IgG-FITC (BD Bioscience) at room temperature for 1 h. For in situ pentamer staining, frozen sections from the salivary gland were stained with CD8α (green), H-2Ld YPHFMPTNL pentamer (red), and DAPI (blue). All incubations were performed in a humidity box, and slides were washed 3 times for 5 min in PBS at room temperature between incubations. Coverslips were mounted using Vectashield aqueous mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Negative controls exhibited little background staining and included control and infected tissues incubated with isotype-matched antibodies (data not shown). Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope with the Nikon Digital Sight DS camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Histology

Spleens were collected from saline-treated (control) or immunized mice, as indicated, and embedded in paraffin, and hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E)-stained sections were used to evaluate pathological changes. Images were obtained on an Olympus CKX41 microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY, USA) and were captured with a Polaroid DMC1 digital microscope camera (Polaroid Corp., Minnetonka, MN, USA).

Plaque assay

Viral titers were determined using a standard plaque assay with slight modifications (8). Tissues were homogenized with a BeadBeater (Biospec), and supernatants were serially diluted in DMEM with 5% fetal calf serum and incubated on 80% confluent monolayers of 3T12 mouse embryo fibroblasts (ATCC) at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were incubated in a 1:1 mixture of 2.4% methylcellulose and 2× complete DMEM for 6–8 d. Cells were fixed and stained with 1% crystal violet, and virus plaques were counted. Virus titers are reported as log pfu per gram tissue. Serum and saliva samples were also assayed for neutralizing activity to MCMV using a plaque reduction neutralization test (15). Samples diluted in DMEM with 5% newborn calf serum and antibiotics were mixed with an equal volume of MCMV containing 1.0 × 103 pfu/ml. DMEM with 5% newborn calf serum and normal mouse serum were used as negative controls. Following an incubation for 90 min at room temperature, the serum-virus mixtures were than inoculated onto monolayers of 3T12 cells in 6-well plates in a volume of 0.4 ml, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C for 60 min to permit adsorption of non-neutralized virus. The inoculum were then removed, and the cells were washed once with 1 ml of PBS and overlaid with complete DMEM containing 1.2% methylcellulose for determination via plaque assay.

Statistical analysis

Student's t test with 2-tailed distribution and 2-sample, unequal variance was performed to determine statistical significance in pair-wise comparisons. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. Data points were excluded from analysis by using Grubb's test for detecting outliers.

RESULTS

Retrograde perfusion via Wharton's duct with tcMCMV induced effective immune responses

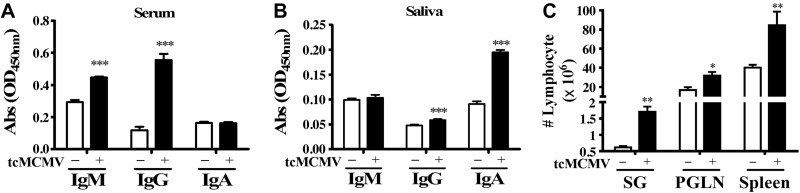

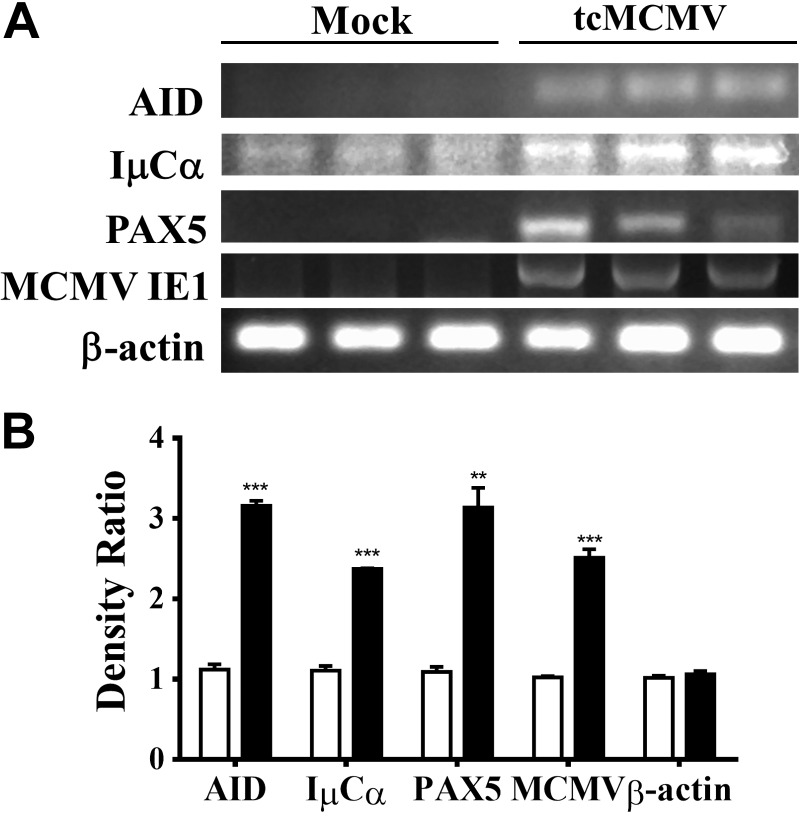

Using retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland to deliver saline (mock treatment) or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV to Balb/cByJ mice (Supplemental Fig. S1), we investigated whether MCMV-specific antibody responses were stimulated in the serum or saliva at 14 d postinoculation (Fig. 1). The data demonstrated that retrograde perfusion generated a serum antibody response characterized by the induction of MCMV-specific IgM and IgG (Fig. 1A) and a saliva antibody response characterized by the induction of IgA (Fig. 1B). Cell yields from the salivary gland after retrograde perfusion with 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV were significantly elevated as compared to the saline (mock treatment) with on average 1.7 × 106 cells recovered from the tcMCMV immunized group vs. 0.6 × 106 cells recovered from the saline group (Fig. 1C). A significant increase in cells recovered from the PGLNs and spleen was also observed (Fig. 1C). An increase in both MCMV-specific antibodies in the serum and in cell yields from the salivary glands and PGLNs after a 21 d prime followed by a 10 d boost was also observed (Supplemental Fig. S2). To investigate events occurring within the salivary glands after retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with tcMCMV, we probed for key mRNA markers of GCs (Fig. 2A). RNA was prepared from whole salivary glands after removal of the associated lymph nodes on d 14, and the relative expression of mRNA for AID, IμCα, PAX5, and the MCMV IE1 protein was determined by comparing the ratio of the indicated mRNA from tcMCMV-inoculated mice vs. saline-inoculated mice (Fig. 2B). We observed significant increases in AID expression, which is essential for antigen stimulation of mature B cells leading to somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination (CSR) (16), in IμCα, which serves as a molecular marker for active IgA CSR (17), and in PAX5, a B-cell lineage commitment factor (18), in tcMCMV inoculated mice vs. saline controls (Fig. 2). mRNA expression of the MCMV protein IE1 verified infection in tcMCMV-inoculated mice. As demonstrated, little to no expression of MCMV IE1 was observed in saline-inoculated mice (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with tcMCMV stimulated MCMV-specific antibodies and increased lymphocyte yields. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized via cannulation with either saline (mock treatment) or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV and evaluated on d 14. A, B) Serum (A) and saliva (B) samples were collected for detection of MCMV-specific IgM, IgG, and IgA antibodies via an MCMV-specific ELISA. C) Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the salivary glands (SG), PGLNs, and spleen, and total cell yields were assessed. Data are means ± sd from 5 mice/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. saline.

Figure 2.

Key markers of GCs were induced after retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with tcMCMV. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized via cannulation with either saline (mock treatment) or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV. RNA was prepared from whole salivary glands after removal of the associated lymph nodes on d 14 after inoculation. A) RNA was analyzed via RT-PCR for expression of AID, IμCα, PAX5, MCMV IE1, and β-actin. B) Histogram represents the densitometric data of the ratio of mock/average mock (open bars) and the ratio of tcMCMV/average mock (solid bars). Data are means ± sd from 3 mice/group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. saline.

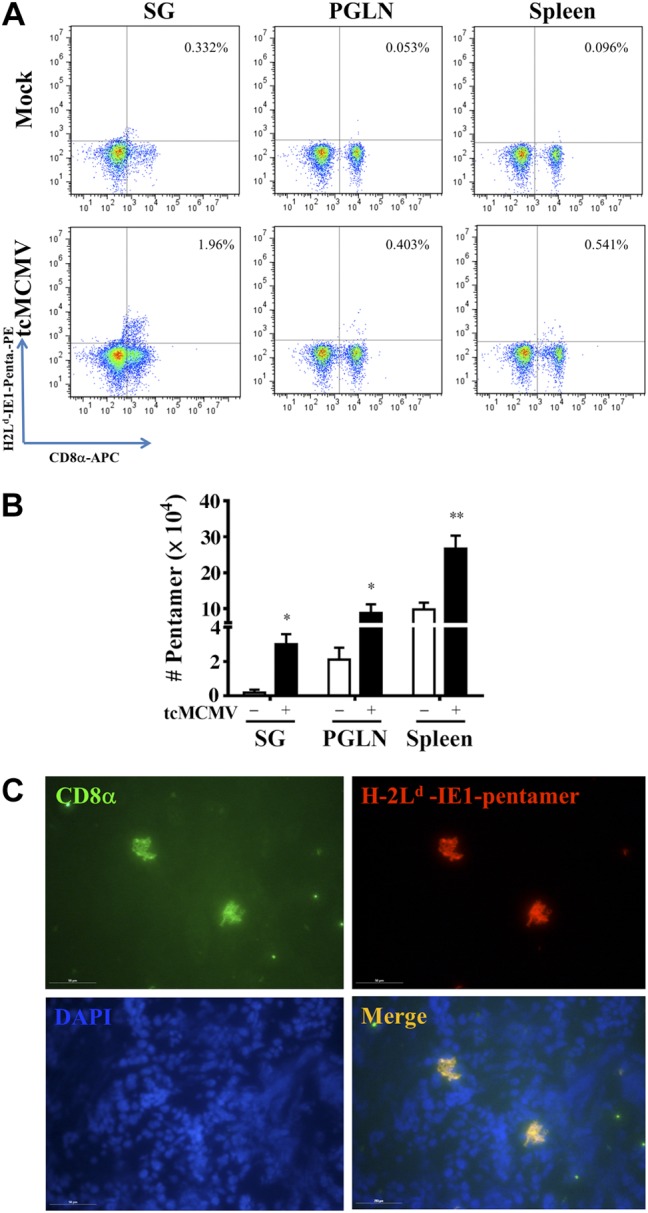

Retrograde perfusion with tcMCMV induced antigen-specific T lymphocytes recognizing an MCMV IE1 immunodominant epitope

To probe for MCMV-specific T-cell responses, we evaluated the CD8+ T cells for a major MCMV cytotoxic T epitope derived from the IE1 gene. For these studies, we chose the H-2Ld YPHFMPTNL pentamer, which is specific for an epitope derived from MCMV IE1 (aa 168–176) in the context of H-2Ld (19). Balb/cByJ mice were immunized via retrograde perfusion with saline (mock) or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV. On d 21 after primary inoculation, mice were boosted with saline or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV and evaluated 10 d after boosting. A significant increase in the percentage of pentamer+ CD8+ T cells was observed in all tissues examined, with the largest increase occurring in the salivary glands (0.32% mock vs. 1.96% tcMCMV; Fig. 3A). When these percentages were normalized to cell yields, the absolute number of CD8+ T lymphocytes that bind the H2Ld YPHFMPTNL pentamer significantly increased in all tissues examined as compared to saline-treated mice (Fig. 3B). In addition, via dual-staining immunofluorescence, we demonstrated the presence of H2Ld YPHFMPTNL pentamer-binding CD8 T cells in the salivary gland from primed and boosted mice (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with tcMCMV increased MCMV antigen-specific T cells. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized via cannulation with either saline (mock treatment) or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV. On d 21 after primary immunization, mice were boosted with either saline or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV and evaluated 10 d after boosting. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the salivary glands, PGLNs, and spleens. A) Cells were first stained with the B-cell marker, CD19, and then CD19− cells were analyzed for expression of the T-cell surface marker, CD8 (x axis) and the MCMV IE1 pentamer (H-2Ld YPHFMPTNL; y axis). Percentage of dual-staining cells is shown in the top right quadrant. Data are representative of 5 individual mice/group demonstrating similar results. B) Histogram demonstrates the absolute numbers of CD8+ pentamer+ T cells from saline-treated (open bars) and tcMCMV-immunized (solid bar) mice. Data are means ± sd from 5 mice/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. saline. C) For in situ pentamer staining, frozen sections from the salivary gland were stained with CD8α (green), H-2Ld YPHFMPTNL pentamer (red), and DAPI (blue). Images were then merged, and dual-positive CD8+/pentamer+ cells (yellow) were observed. View: ×40. Scale bars = 50 μM. Images are representative of 5 mice/group demonstrating similar results.

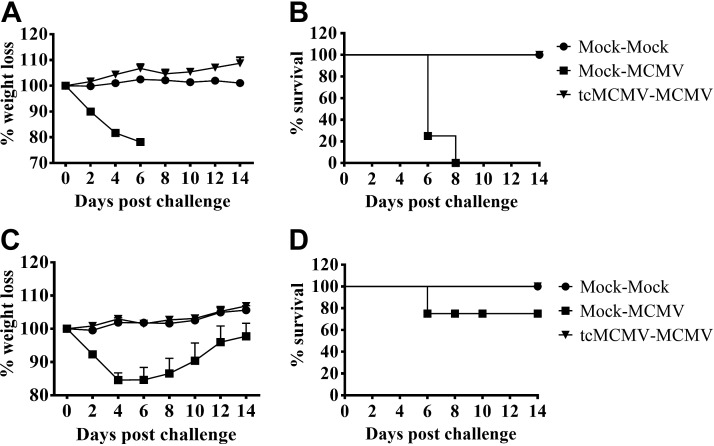

Retrograde perfusion with tcMCMV protected against a lethal systemic challenge with MCMV

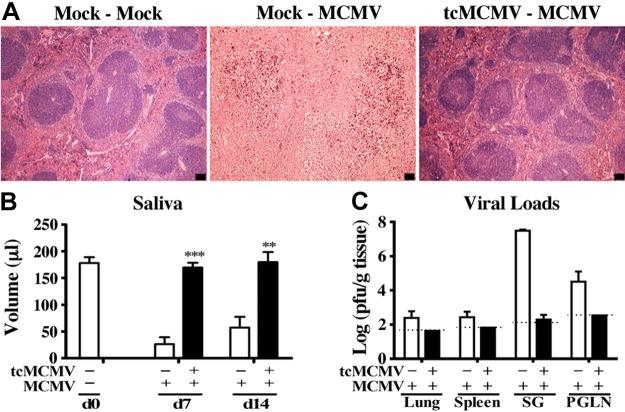

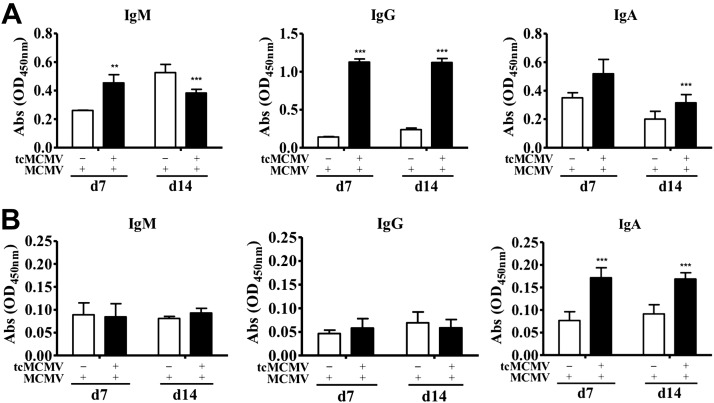

To determine whether retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with tcMCMV conferred protection against a lethal systemic challenge with MCMV, Balb/cByJ mice were inoculated with saline (mock treatment) or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV, and were challenged i.p. on d 28 with either 2 × 104 or 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV. When challenged with a lethal inoculum of MCMV (5×104 pfu/mouse), all mice inoculated via retrograde perfusion with saline lost significant weight (Fig. 4A) and all died by d 8 postchallenge (Fig. 4B). When challenged with a sublethal inoculum of MCMV (2×104 pfu/mouse), saline-inoculated mice initially lost ∼20% body weight during the first week postchallenge, but this weight loss was reversed over the following week (Fig. 4C). Only one saline-inoculated mouse died after sublethal challenge (Fig. 4D). Mice inoculated via retrograde perfusion with 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV and challenged with either a lethal (5×104 pfu/mouse; Fig. 4A, B) or sublethal (2×104 pfu/mouse; Fig. 4C, D) inoculum of MCMV were protected from weight loss (Fig. 4A, C) and all mice survived lethal challenge (Fig. 4B). The spleen was examined histologically for evidence of MCMV-induced pathology on d 14 postchallenge. In mice inoculated with saline via retrograde perfusion and challenged i.p. with 2 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV, significant splenic necrosis was evident (Fig. 5A, mock-MCMV). However, in mice inoculated with 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV via retrograde perfusion and challenged i.p. with 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV, the splenic architecture was preserved (Fig. 5A, tcMCMV-MCMV). In addition to histology, salivary output (production of saliva) was measured on d 7 and 14 (Fig. 5B) and viral titers in the lung, spleen, salivary gland and PGLNs were measured on d 14 (Fig. 5C) after challenge with MCMV. In mice inoculated with saline and challenged with MCMV, salivary output was significantly diminished on both d 7 and 14 as compared to control mice (20). However, mice were protected from diminished salivary production when inoculated with 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV prior to challenge with MCMV, demonstrating a similar saliva output as control mice (Fig. 5B). Similarly, viral titers were significantly reduced to the limit of detection in all examined tissues from mice inoculated with tcMCMV as compared to saline-inoculated mice after lethal challenge (Fig. 5C). In addition, mice inoculated with 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV via retrograde perfusion prior to challenge with MCMV generated significant levels of IgM and IgG in the serum (Fig. 6A) and IgA in the saliva (Fig. 6B) on d 7 and 14 after lethal challenge. The development of serum MCMV specific antibodies observed over a 6-wk time course was also evaluated with similar results (Supplemental Fig. S3). MCMV-neutralizing antibodies were detected in the serum after both retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with tcMCMV (Table 1, tcMCMV-mock) and after lethal systemic challenge with MCMV (Table 1, tcMCMV-MCMV).

Figure 4.

Retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with tcMCMV protected mice from a lethal systemic challenge with MCMV. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized via cannulation with saline (mock treatment) or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV. A, B) On d 28 after immunization, mice inoculated with saline via cannulation were challenged i.p. with either saline (mock-mock) or 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV (mock-MCMV). Mice immunized with 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV via cannulation were challenged i.p. with 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV (tcMCMV-MCMV). C, D) On d 28 after immunization, mice inoculated with saline via cannulation were challenged i.p. with either saline (mock-mock) or 2 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV (mock-MCMV). Mice immunized with 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV via cannulation were challenged i.p. with 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV (tcMCMV-MCMV). Weight loss (A, C) and survival (B, D) were monitored for 14 d postchallenge. Weight loss data are means ± sd from 5 mice/group. Survival data are from 5 individual mice/group.

Figure 5.

Retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with tcMCMV limited systemic pathology, prevented diminished salivary output, and lowered viral titers after a lethal challenge with MCMV. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized with saline (mock treatment) or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV via cannulation. On d 28 after immunization, mice were challenged i.p. with 2 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV for saline-inoculated mice and 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV for tcMCMV-immunized mice. A) Spleens were harvested on d 14 postchallenge for assessment of pathological changes on H&E stain. Images are representative of 2 experiments with 3 mice/group demonstrating similar results. View: ×4. Scale bars = 100 μm. B) Saliva was collected and measured at the indicated time points after i.p. MCMV challenge. Data are means ± sd from 5 mice/group/time point. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. saline. C) Viral titers from the lung, spleen, salivary gland, and PGLNs were determined 14 d postchallenge by standard plaque assay. Data are means ± sd from 5 mice/group. Dashed lines represent limit of detection for each tissue. Statistical differences were not available since no detectable virus was found from lung, spleen, and PGLN, and only 1 of 5 salivary glands had a very low viral titer.

Figure 6.

Retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with tcMCMV induced MCMV specific antibodies after a lethal challenge with MCMV. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized with saline (mock treatment) or 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV via cannulation. On d 28 after immunization, saline-inoculated mice were challenged i.p. with 2 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV, and tcMCMV-immunized mice were challenged i.p. with 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV. Serum (A) and saliva (B) samples were collected on d 7 and 14 postchallenge. MCMV-specific IgM, IgG, and IgA antibodies were determined via an MCMV-specific ELISA. Data are means ± sd of 5 mice/group/time point. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. saline.

Table 1.

Neutralizing MCMV Abs after retrograde perfusion with tcMCMV

| Groupa | Reduction of infectivity (%)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1:2 | 1:10 | 1:50 | |

| tcMCMV-mock | 93.58 ± 4.63 | 52.86 ± 23.54 | 45.57 ± 22.58 |

| tcMCMV-MCMV | 98.72 ± 1.28 | 74.24 ± 5.87 | 81.9 ± 2.56 |

Balb/cByJ mice were immunized with 105 pfu/mouse tcMCMV via retrograde perfusion. On d 28 after inoculation, tcMCMV-inoculated mice were challenged i.p. with 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV.

Serum samples collected on d 14 postchallenge were diluted 1:2, 1:10, and 1:50 in DMEM with 5% newborn calf serum and antibiotics and evaluated for neutralizing MCMV Abs, as described in Materials and Methods.

Retrograde perfusion with a replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus expressing an individual MCMV gene elicited an effective immune response

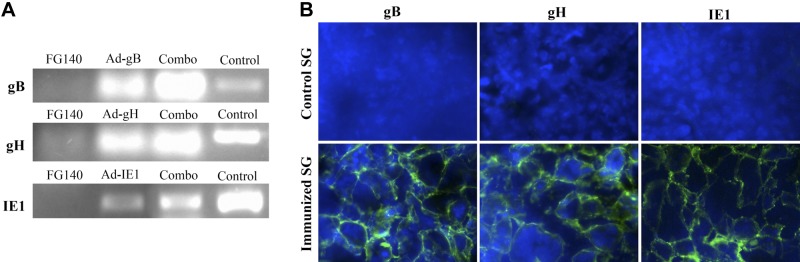

To determine whether retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with a protein antigen elicited an effective immune response, Balb/cByJ mice were immunized (d 0) and boosted (d 30) with saline (mock treatment) or 106 pfu/mouse of a replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus expressing gB (Ad-gB), gH (Ad-gH), or IE1 (Ad-IE1) of MCMV or a combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1 (Ad-combo). Mice immunized with an equivalent amount of FG140, the replication-deficient adenovirus lacking the MCMV inserts, was used as a negative control. gB-, gH-, and IE1-specific RNA were detected in mice immunized in the salivary gland with the analogous replication deficient adenovirus (Fig. 7A). Mice immunized with a combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1 replication-deficient adenovirus (Ad-combo) or MCMV as a positive control also expressed RNA for gB, gH, and IE1. Mice immunized with FG140 (negative control) did not express RNA specific for gB, gH, or IE1. RNA was also prepared from the PGLNs, spleen, and mesenteric lymph nodes of inoculated mice, and no RNA specific for gB, gH, or IE1 was detected (not shown). To directly confirm that the recombinant genes were expressed at the protein level, frozen sections of salivary glands were stained with monoclonal antibodies specific for MCMV gB, gH, or IE1 (FITC, green) and specific protein expression of the indicated MCMV proteins was detected in mice immunized with the analogous replication-deficient adenovirus (Fig. 7B). Salivary glands from saline-inoculated mice served as negative controls.

Figure 7.

Individual MCMV genes are expressed in the salivary glands after retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized (d 0) and boosted (d 30) with either saline (mock) or 106 pfu/mouse of FG140 (negative control), Ad-gB, Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, or a combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1. A) RNA was prepared from salivary glands after removal of the associated lymph nodes on d 30 after boost immunization and analyzed via RT-PCR for expression of MCMV gB (top panel), gH (middle panel), or IE1 (bottom panel). RNA from MCMV infected salivary glands served as a positive control. Data are representative of 2 experiments with 3 mice/group. B) Frozen sections of salivary glands were stained with monoclonal antibodies specific for MCMV gB, gH, or IE1 (FITC, green) and DAPI (blue). Salivary glands from saline (mock)-infected mice served as negative controls. View: ×40. Images are representative of 2 experiments with 3 mice/group demonstrating similar results.

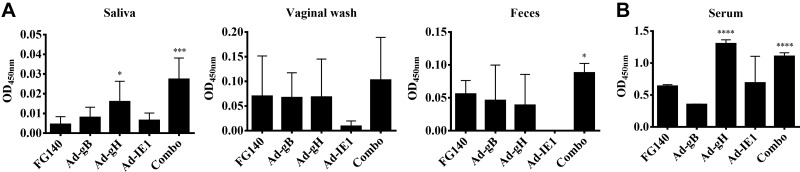

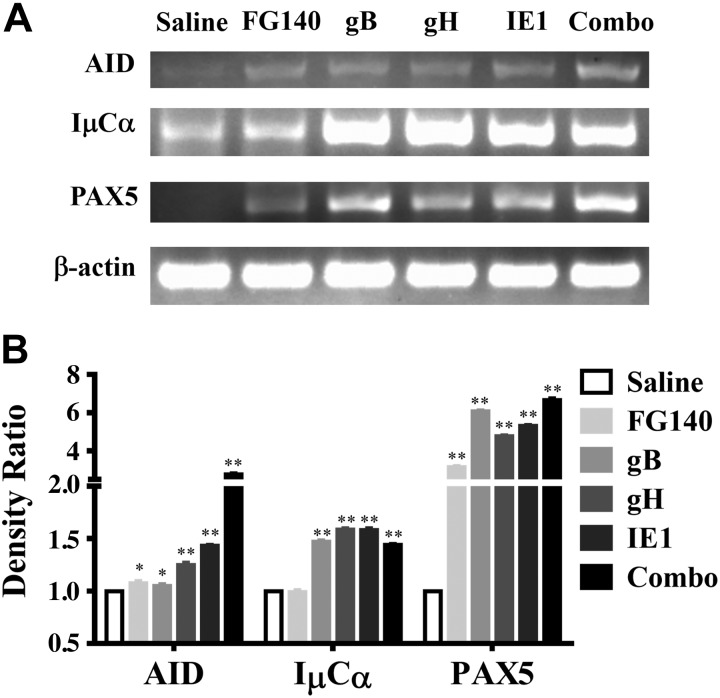

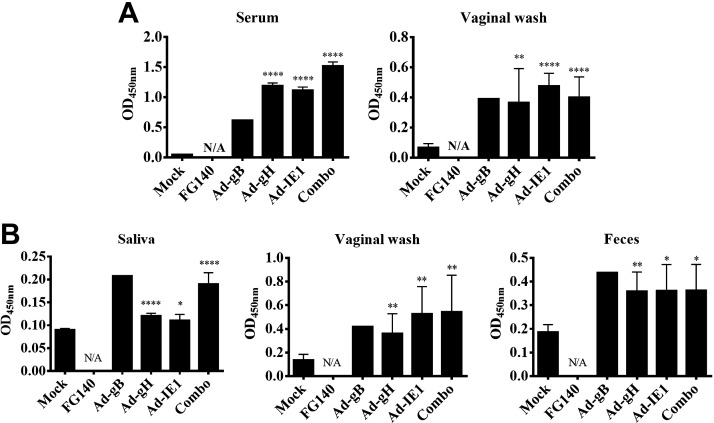

Since we demonstrated localized expression of individual MCMV proteins in the salivary glands after retrograde perfusion, we next determined whether a mucosal and/or systemic MCMV-specific antibody response was induced. MCMV-specific IgA was observed from saliva samples after retrograde perfusion with Ad-gH or the combination expressing Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1 (Fig. 8A). Only immunization with the combination (Ad-combo) generated MCMV-specific IgA in fecal samples (Fig. 8A). While an increase in IgA was observed in the vaginal wash after immunization with Ad-gB, Ad-gH, or Ad-IE1, this increase was not statistically significant (Fig. 8A). Retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with Ad-gH and the combination expressing Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1 also induced MCMV-specific IgG antibodies in the serum (Fig. 8B). In addition, after retrograde perfusion with Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, or the combination expressing Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1, MCMV neutralizing antibodies were present in the serum and saliva (Table 2). We also probed for GC formation via the relative expression of mRNA for AID, IμCα, and PAX5 (Fig. 9A). After retrograde perfusion with Ad-gB, Ad-gH, Ad-IE1 or the combination expressing Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1, we observed significant increases in AID expression, in IμCα expression, and in PAX5 expression vs. saline-treated controls (Fig. 9B). After retrograde perfusion with FG140, we observed significant increases in AID and PAX5 only (Fig. 9B). We did not observe an increase in IμCα, which served as a molecular marker for active IgA CSR (17) in FG140-immunized mice (Fig. 9B).

Figure 8.

Retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with replication-deficient recombinant adenoviruses expressing individual MCMV genes elicited mucosal and humoral antibodies. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized (d 0) and boosted (d 30) with 106 pfu/mouse of FG140 (negative control), Ad-gB, Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, or a combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1. Saliva, vaginal wash, and feces (A) and serum samples (B) were collected on d 30 after boost immunization for detection of MCMV-specific IgA antibodies (A) and IgG antibodies (B) via an MCMV-specific ELISA. Data are means ± sd of 5 mice/group. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. FG140.

Table 2.

Neutralizing MCMV Abs after retrograde perfusion with replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus expressing individual MCMV genes

| Groupa | Reduction of infectivity (%)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum, 1:10c | Saliva |

||

| 1:20 | 1:100 | ||

| FG140 | 0 ± 0.00 | 5.38 ± 1.86 | 4.41 ± 1.86 |

| Ad-gB | 0 ± 0.00 | 12.90 ± 9.12 | 10.97 ± 6.84 |

| Ad-gH | 97.5 ± 3.54 | 19.35 ± 9.12 | 8.07 ± 7.41 |

| Ad-IE1 | 25 ± 20.00 | 13.98 ± 7.55 | 8.28 ± 6.24 |

| Combo | 50 ± 28.28 | 18.25 ± 11.39 | 12.26 ± 7.07 |

Balb/cByJ mice were immunized via retrograde perfusion (d 0) and boosted (d 30) with 106 pfu/mouse of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, or a combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1. Immunization with FG140 served as a negative control.

Serum or saliva samples collected on d 30 after boost were diluted as indicated in DMEM with 5% newborn calf serum and antibiotics and evaluated for neutralizing MCMV Abs, as described in Materials and Methods.

All serum samples demonstrated no virus neutralizing activity at a 1:50 dilution.

Figure 9.

Key markers of GCs were induced after retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with replication-deficient recombinant adenoviruses expressing individual MCMV genes. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized (d 0) and boosted (d 30) with 106 pfu/mouse of FG140 (negative control), Ad-gB, Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, or a combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1. RNA was prepared from whole salivary glands after removal of the associated lymph nodes on d 30 after boost immunization. A) RNA was analyzed via RT-PCR for expression of AID, IμCα, PAX5, and β-actin. Images are representative of 5 mice/group demonstrating similar results. B) Histogram represents the densitometric data of the ratio of mock/average mock (solid bars) and the ratio of individual MCMV genes/average mock. Data are means ± sd of 5 mice/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. mock treatment.

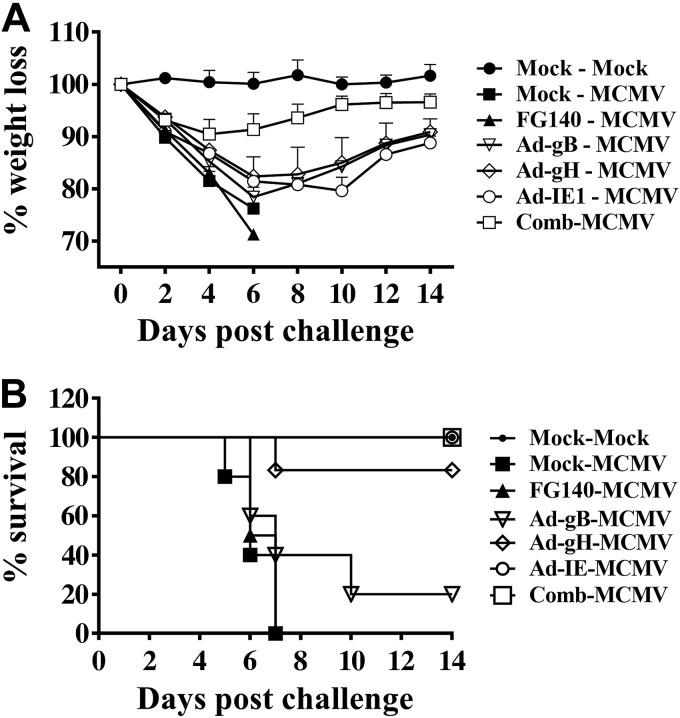

Retrograde perfusion with replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus expressing individual MCMV genes protected against a lethal systemic challenge with MCMV

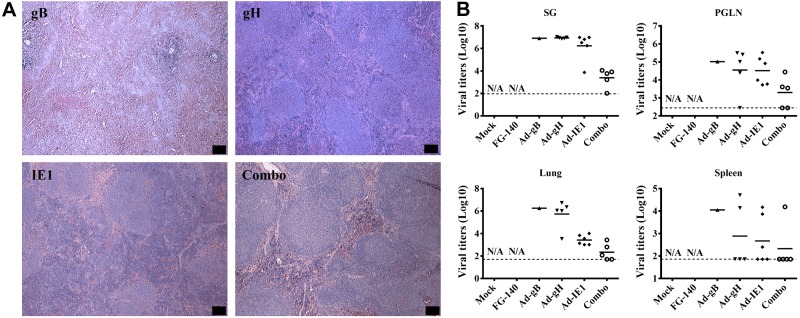

To determine whether retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with a nonreplicating or protein antigen conferred protection against a lethal systemic challenge with MCMV, Balb/cByJ mice were immunized (d 0) and boosted (d 30) with saline (mock treatment) or 106 pfu/mouse of FG140, Ad-gB, Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, or a combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1. On d 30 after boost immunization, mice inoculated with saline were challenged i.p. with saline (Fig. 10, mock-mock) or 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV (Fig. 10, mock-MCMV). Mice inoculated with 106 pfu/mouse of FG140, or replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus expressing MCMV genes were challenged i.p. with 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV (Fig. 10, Ad-MCMV). All mice inoculated via retrograde perfusion with saline or FG140 lost significant body weight (Fig. 10A), and all died by d 7 after lethal challenge (Fig. 10B). However, mice inoculated with the combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1 were protected from significant weight loss (Fig. 10A), and all mice survived lethal challenge (Fig. 10B). While mice inoculated with Ad-gB, Ad-gH, or Ad-IE1 initially lost body weight (∼20%) during the first week postchallenge, this weight loss was reversed over the following week (Fig. 10A). In regard to survival, 100% of mice immunized with Ad-IE1 (6/6 mice) and 83% of mice immunized with Ad-gH (5/6 mice) survived lethal challenge (Fig. 10B). However, only 20% of mice immunized with Ad-gB (1/5 mice) survived lethal challenge beyond d 10 (Fig. 10B).

Figure 10.

Retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with replication-deficient recombinant adenoviruses expressing individual MCMV genes protected mice from a lethal systemic challenge with MCMV. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized (d 0) and boosted (d 30) with either saline (mock treatment) or 106 pfu/mouse of FG140 (negative control), Ad-gB, Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, or a combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1. On d 30 after boost immunization, mice inoculated with saline were challenged i.p. with either saline (mock-mock) or 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV (mock-MCMV). Mice immunized with replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus were challenged i.p. with 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV (Ad-MCMV). Weight loss (A) and survival (B) were monitored for 14 d after lethal challenge. Data are means ± sd from 5 mice/group.

The spleen was examined histologically for evidence of MCMV-induced pathology on d 14 postchallenge. In mice immunized with Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, and the combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1, splenic architecture was preserved after lethal challenge (Fig. 11A). In contrast, in mice immunized with Ad-gB, significant splenic necrosis was evident (Fig. 11A). In addition to histology, viral titers were significantly reduced in all tissues examined from mice immunized via retrograde perfusion with the combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1 (Fig. 11B). Mice immunized with Ad-gB, Ad-gH, or Ad-IE1 demonstrated similar viral titers as compared to saline-inoculated mice after a sublethal challenge (Figs. 11B vs. 5C). Finally, on d 14 after lethal challenge, mice immunized with Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, and the combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1 expressed a greater amount of MCMV-specific IgG in the serum (Fig. 12A) and MCMV-specific IgA in the saliva, vaginal wash, and feces (Fig. 12B) as compared to prime and boosted mice only (Fig. 8). MCMV-specific IgG was also present in the vaginal wash (Fig. 12A). Taken together, these data demonstrate that an effective adaptive immune response was stimulated in mice immunized with replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus expressing individual MCMV genes via retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland.

Figure 11.

Retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with replication-deficient recombinant adenoviruses expressing individual MCMV genes limited systemic pathology and lowered viral titers after a lethal challenge with MCMV. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized (d 0) and boosted (d 30) with either saline (mock treatment) or 106 pfu/mouse of FG140 (negative control), Ad-gB, Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, or a combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1. On d 30 after boost immunization, mice inoculated with saline were challenged i.p. with either saline (mock-mock) or 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV (mock-MCMV). Mice immunized with replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus were challenged i.p. with 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV (Ad-MCMV). A) Spleens were harvested on d 14 postchallenge for assessment of pathological changes on H&E stain. Images are representative of 5 mice/group demonstrating similar results. View: ×4. Scale bars = 100 μm. B) Viral titers from the salivary gland, PGLNs, lung, and spleen were determined 14 d postchallenge by standard plaque assay. Dashed lines represent the limit of detection for each tissue. Data are from 5 mice/group. Statistical differences were not available (N/A) since there were no surviving animals in the mock and FG140 control groups.

Figure 12.

Retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with replication-deficient recombinant adenoviruses expressing individual MCMV genes induced MCMV-specific antibodies after a lethal challenge with MCMV. Balb/cByJ mice were immunized (d 0) and boosted (d 30) with either saline (mock treatment) or 106 pfu/mouse of FG140 (negative control), Ad-gB, Ad-gH, Ad-IE1, or a combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1. On d 30 after boost immunization, all mice were challenged i.p. with 5 × 104 pfu/mouse MCMV. Samples were collected from surviving mice for analysis of MCMV-specific antibodies at 14 d postchallenge. All mice immunized with FG140 and 5/6 mice immunized with Ad-gB died after lethal challenge. A) MCMV-specific IgG was measured from the serum and vaginal wash. B) MCMV-specific IgA was measured from saliva, vaginal wash, and feces. Data are means ± sd of 5 mice/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 vs. saline.

DISCUSSION

Effective immunization strategies are necessary to reduce the burden of disease from pathogens, especially viruses, that initiate their infectious processes at mucosal surfaces; thus, understanding the mechanisms of defense in these tissues is an important endeavor in vaccine development (1, 4–6). Most vaccines are given parentally via injection, and they do not necessarily generate an adequate immune response at mucous membranes. Therefore, it is important that the evaluation of vaccine candidates address the induction of both mucosal and systemic immunity that would be reflected in prevention of infection or reduction in pathogen replication at the initial site of pathogen entry. The salivary glands are important mucosal tissues in the oral cavity and upper gastrointestinal tract. Salivary glands physiologically produce and secrete into the saliva a variety of beneficial proteins that have important roles in maintaining tissue homeostasis and integrity (21). Due to several physical and biological characteristics, the salivary glands can potentially be a unique target site for the induction of both mucosal and systemic immunity (22, 23). The salivary glands have also been shown to be a valuable target tissue for gene therapeutics after retrograde perfusion (24, 25). Using this technique, a phase I clinical trial evaluated the safety and biological efficacy of adenoviral-mediated aquaporin-1 cDNA transfer to a single previously irradiated parotid gland, demonstrating that transfer of aquaporin-1 cDNA increased parotid flow and relieved symptoms in a subset of subjects (26). In animal models, retrograde perfusion with modified vectors successfully led to the expression of human α-1-antitrypsin, human erythropoietin, and human keratinocyte growth factor (27–30).

In this study, we addressed a fundamental gap in identifying effective strategies for mucosal immunization via the salivary gland. Using a novel method of focused salivary gland inoculation, retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland via Wharton's duct (13), we demonstrated that the submandibular salivary gland functions as an inductive site in the context of the common mucosal immune system and after immunization with tcMCMV developed MCMV-specific B- and T-cell immunity including the generation of neutralizing Abs to MCMV in the serum and saliva. The formation of GCs was confirmed via increased expression of key mRNA markers including AID, IμCα, and PAX5, as we had previously demonstrated after a direct intraglandular inoculation with tcMCMV (9). MCMV-specific CD8 restricted T cells directed toward a major MCMV epitope derived from the IE1 gene were demonstrated within the salivary gland infiltrating lymphocytes. Finally, salivary gland cannulation with tcMCMV protected against a systemic challenge with a lethal dose of MCMV. The results described in these studies extend our previous studies where the salivary glands were directly inoculated with tcMCMV via a surgical route (9). Therefore, this physiological route of inoculation was able to induce an adaptive immune response via the submandibular salivary gland, and thus has the potential to be further developed into a strategy for the induction of protective immune responses to additional mucosal pathogens.

While we have demonstrated that direct injection (9) or retrograde perfusion of the salivary gland resulted in the induction of a protective immune response using an attenuated (tcMCMV) viral system, to be generally applicable as a site for vaccination, it was necessary to demonstrate that direct protein expression in the salivary gland such as that delivered via a noninfectious, conventional subunit vaccine, could also elicit effective and functionally protective immunity. Recombinant adenoviruses are a versatile tool for gene delivery and expression, since they are able to infect a broad range of cell types, and infection is not dependent on active host cell division (31, 32). The most commonly used adenoviral vectors are typically devoid of E1 and E3 genes, which not only render the virus incapable of replication but also make room for the insertion of up to 7.5 kb of foreign DNA (33, 34). In this study, we employed replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus to deliver the MCMV gB, gH, or IE1 genes to the salivary gland via Wharton's duct. We demonstrated that individual MCMV genes were transcribed and translated into proteins that were limited to the salivary glands and were not detected in the PGLNs, spleen, or mesenteric lymph nodes. Salivary gland immunization with these replication deficient recombinant adenovirus induced mucosal neutralizing MCMV-specific IgA at the primary immunization site (saliva), MCMV-specific IgA at distal mucosal sites (feces and vagina), and systemic neutralizing MCMV-specific IgG in the serum. Finally, mice were protected against a lethal systemic challenge, as evidenced by increased survival rates, decreased viral titers in systemic tissues, and protection against splenic pathology observed following systemic infection with MCMV. These results confirm those of Shanley and Wu (11, 12), who utilized the intranasal route of immunization with replication-deficient adenovirus expressing gB or gH for the generation of MCMV-specific mucosal and systemic immunity (11, 12). They demonstrated that after both a primary and secondary immunization with either Ad-gB or Ad-gH via the intranasal route neutralizing antibodies to MCMV were detected in the serum, and antibodies to MCMV were detected in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, fecal suspensions, and vaginal washes (11, 12). Viral titers were also significantly reduced in both the lungs and salivary glands after mice were challenged with a sublethal dose of MCMV via the intranasal route (11, 12). Here, we extended these finding by demonstrating that immunization of the salivary glands, the primary site of MCMV replication, via a physiological route (retrograde perfusion) with replication-deficient recombinant subunit adenovirus vaccines induced a 2- to 6-fold increase in systemic and mucosal MCMV-specific antibodies, a 3- to 6-fold increase in GC marker expression, and protected against a lethal systemic challenge, as evidenced by up to 80% increased survival, decreased splenic pathology and decreased viral titers. In comparison to the findings of Shanley and Wu (11, 12), we found that immunization with Ad-gH was far superior to immunization with Ad-gB when mice were challenged with a lethal dose of MCMV (80% protection for Ad-gH vs. 20% protection for Ad-gB). In addition, we found that immunization with Ad-IE1, as well as the combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1, provided 100% protection when mice were challenged with a lethal dose of MCMV. Further, while immunization with Ad-IE1 and the combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1 provided 100% protection, by comparison, immunization with the combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1 induced higher titers of MCMV-specific IgA in the saliva and feces and MCMV-specific IgG in the serum after primary/boost immunizations as compared to immunization with Ad-IE1 alone. The combination of Ad-gB, Ad-gH, and Ad-IE1 was also superior in GC formation (as evidenced by a substantially higher increase in AID mRNA expression) and in reducing infectious virions in the salivary gland, PGLN, lung, and spleen after lethal challenge as compared to immunization with Ad-IE1 alone. Thus, our data clearly support the idea that a multivalent MCMV subunit vaccine is superior to a monovalent MCMV vaccine, even when a monovalent vaccine such as Ad-IE1 provides 100% protection against a lethal challenge with MCMV.

Understanding the immunobiology of the salivary glands is also of particular interest at this time because of rapidly developing progress in gene therapy and tissue engineering as it relates to the salivary glands. The ability to “reengineer” the salivary glands via gene transfer in vivo with the resultant in situ restoration of fluid secretion (35, 36) and to utilize salivary endocrine secretory pathways for systemic gene therapeutics (37–39) provides additional reasons for gaining a better understanding of how salivary gland immunity interacts with the expression of transferred genes, especially because the transferred genes are frequently expressed utilizing recombinant viral vectors. In this regard, Zheng et al. (40) described a method of direct intraoral cannulation of the parotid gland via Stensen's ducts and demonstrated using recombinant serotype 5 adenoviral vectors that mouse parotid glands can also be conveniently and reproducibly targeted for gene transfer (40). Studies involving gene transfer to nonhuman primate salivary glands (41, 42) and human salivary glands (43) also utilized the parotid gland. These studies demonstrated that parotid glands can be conveniently and reproducibly targeted for gene transfer and therefore may be useful models for preclinical studies for a number of disease models. However, at this point in time, whether the parotid gland can also act as a mucosal inductive site in a murine model system or in humans has not been determined and is of clinical importance since translational studies in humans will most likely use the parotid glands since they are well encapsulated with associated lymph nodes and have a relatively straight main secretory duct.

In summary, we demonstrated that immunization via retrograde perfusion of the submandibular gland with a nonreplicating antigen focused to the salivary gland resulted in the induction of a protective immune response at both mucosal and systemic sites, thus strongly supporting the concept that salivary gland immunization can serve as an alternative mucosal route for administering vaccines for the induction of protective mucosal immune response to pathogens that impinge on mucosal surfaces including viruses and bacteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Changyu Zheng (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) for providing training in the salivary gland cannulation technique. The authors also thank Drs. John D. Shanley and Carol A. Wu (University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA) for providing recombinant adenovirus vectors and cell lines.

This project was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grant 1R01 DE016652 (S.D.L.).

The work described in this manuscript has not been previously published and is not being considered concurrently by another publication. All authors concur with this submission. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- Ad

- adenovirus

- AID

- activation-induced cytidine deaminase

- CSR

- class switch recombination

- GC

- germinal center

- H&E

- hematoxylin and eosin

- MCMV

- murine cytomegalovirus

- PAX5

- paired box protein 5

- pfu

- plaque forming unit

- PGLN

- periglandular lymph node

- tcMCMV

- tissue culture-derived murine cytomegalovirus

REFERENCES

- 1. Brandtzaeg P. (2007) Induction of secretory immunity and memory at mucosal surfaces. Vaccine 25, 5467–5484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brandtzaeg P., Baekkevold E. S., Farstad I. N., Jahnsen F. L., Johansen F. E., Nilsen E. M., Yamanaka T. (1999) Regional specialization in the mucosal immune system: what happens in the microcompartments? Immunol. Today 20, 141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Macpherson A. J., McCoy K. D., Johansen F. E., Brandtzaeg P. (2008) The immune geography of IgA induction and function. Mucosal. Immunol. 1, 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takahashi I., Nochi T., Yuki Y., Kiyono H. (2009) New horizon of mucosal immunity and vaccines. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 21, 352–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neutra M. R., Kozlowski P. A. (2006) Mucosal vaccines: the promise and the challenge. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 148–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tucker S. N., Lin K., Stevens S., Scollay R., Bennett M. J., Olson D. C. (2004) Salivary gland genetic vaccination: a scalable technology for promoting distal mucosal immunity and heightened systemic immune responses. Vaccine 22, 2500–2504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Woodrow K. A., Bennett K. M., Lo D. D. (2012) Mucosal vaccine design and delivery. Ann. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 14, 17–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pilgrim M. J., Kasman L., Grewal J., Bruorton M. E., Werner P., London L., London S. D. (2007) A focused salivary gland infection with attenuated MCMV: an animal model with prevention of pathology associated with systemic MCMV infection. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 82, 269–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grewal J. S., Pilgrim M. J., Grewal S., Kasman L., Werner P., Bruorton M. E., London S. D., London L. (2011) Salivary glands act as mucosal inductive sites via the formation of ectopic germinal centers after site-restricted MCMV infection. FASEB J. 25, 1680–1696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brune W., Hengel H., Koszinowski U. H. (2001) A mouse model for cytomegalovirus infection. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 19, Unit 19.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shanley J. D., Wu C. A. (2005) Intranasal immunization with a replication-deficient adenovirus vector expressing glycoprotein H of murine cytomegalovirus induces mucosal and systemic immunity. Vaccine 23, 996–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shanley J. D., Wu C. A. (2003) Mucosal immunization with a replication-deficient adenovirus vector expressing murine cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B induces mucosal and systemic immunity. Vaccine 21, 2632–2642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuriki Y., Liu Y., Xia D., Gjerde E. M., Khalili S., Mui B., Zheng C., Tran S. D. (2011) Cannulation of the mouse submandibular salivary gland via the Wharton's duct. J. Vis. Exp. 14, 3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu G., Kahan S. M., Jia Y., Karst S. M. (2009) Primary high-dose murine norovirus 1 infection fails to protect from secondary challenge with homologous virus. J. Virol. 83, 6963–6968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmidt N. J., Dennis J., Lennette E. H. (1976) Plaque reduction neutralization test for human cytomegalovirus based upon enhanced uptake of neutral red by virus-infected cells. J. Clin. Microbiol. 4, 61–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tarlinton D., Radbruch A., Hiepe F., Dorner T. (2008) Plasma cell differentiation and survival. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20, 162–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Honjo T., Kinoshita K., Muramatsu M. (2002) Molecular mechanism of class switch recombination: linkage with somatic hypermutation. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 20, 165–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klein U., Dalla-Favera R. (2008) Germinal centres: role in B-cell physiology and malignancy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 22–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bohm V., Podlech J., Thomas D., Deegen P., Pahl-Seibert M. F., Lemmermann N. A., Grzimek N. K., Oehrlein-Karpi S. A., Reddehase M. J., Holtappels R. (2008) Epitope-specific in vivo protection against cytomegalovirus disease by CD8 T cells in the murine model of preemptive immunotherapy. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 197, 135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kasman L. M., London L. L., London S. D., Pilgrim M. J. (2009) A mouse model linking viral hepatitis and salivary gland dysfunction. Oral Diseases 15, 587–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Amerongen A. V. N., Veerman E. C. I. (2002) Saliva – the defender of the oral cavity. Oral Diseases 8, 12–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zufferey R., Aebischer P. (2004) Salivary glands and gene therapy: the mouth waters. Gene Ther. 11, 1425–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baum B. J., Voutetakis A., Wang J. (2004) Salivary glands: novel target sites for gene therapeutics. Trends Mol. Med. 10, 585–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Omnell K. A., Qwarnstrom E. E. (1983) A technique for intraoral cannulation and infusion of the rat submandibular gland. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 12, 13–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Samuni Y., Baum B. J. (2011) Gene delivery in salivary glands: from the bench to the clinic. Biochim. Biophys 1812, 1515–1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baum B. J., Alevizos I., Zheng C., Cotrim A. P., Liu S., McCullagh L., Goldsmith C. M., Burbelo P. D., Citrin D. E., Mitchell J. B., Nottingham L. K., Rudy S. F., Van Waes C., Whatley M. A., Brahim J. S., Chiorini J. A., Danielides S., Turner R. J., Patronas N. J., Chen C. C., Nikolov N. P., Illei G. G. (2012) Early responses to adenoviral-mediated transfer of the aquaporin-1 cDNA for radiation-induced salivary hypofunction. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 109, 19403–19407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zheng C., Cotrim A. P., Rowzee A., Swaim W., Sowers A., Mitchell J. B., Baum B. J. (2011) Prevention of radiation-induced salivary hypofunction following hKGF gene delivery to murine submandibular glands. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 2842–2851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perez P., Adriaansen J., Goldsmith C. M., Zheng C., Baum B. J. (2011) Transgenic alpha-1-antitrypsin secreted into the bloodstream from salivary glands is biologically active. Oral Dis. 17, 476–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zheng C., Baum B. J. (2012) Including the p53 ELAV-like protein-binding site in vector cassettes enhances transgene expression in rat submandibular gland. Oral Dis. 18, 477–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zheng C., Cotrim A. P., Nikolov N., Mineshiba F., Swaim W., Baum B. J. (2012) A novel hybrid adenoretroviral vector with more extensive E3 deletion extends transgene expression in submandibular glands. Hum. Gene Therapy Methods 23, 169–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Massie B., Couture F., Lamoureux L., Mosser D. D., Guilbault C., Jolicoeur P., Bélanger F., Langelier Y. (1998) Inducible overexpression of a toxic protein by an adenovirus vector with a tetracycline-regulatable expression cassette. J. Virol. 72, 2289–2296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ogorelkova M., Mehdy Elahi S., Gagnon D., Massie B. (2003) DNA delivery to cells in culture. Methods Mol. Biol. 246, 15–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Benihoud K., Yeh P., Perricaudet M. (1999) Adenovirus vectors for gene delivery. Curr. Opin. Bio/Technol. 10, 440–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Russell W. C. (2000) Update on adenovirus and its vectors. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 2573–2604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baum B. J. (2000) Prospects for re-engineering salivary glands. Adv. Dent. Res. 14, 84–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gao R., Yan X., Zheng C., Goldsmith C. M., Afione S., Hai B., Xu J., Zhou J., Zhang C., Chiorini J. A., Baum B. J., Wang S. (2011) AAV2-mediated transfer of the human aquaporin-1 cDNA restores fluid secretion from irradiated miniature pig parotid glands. Gene Ther. 18, 38–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Voutetakis A., Wang J., Baum B. J. (2004) Utilizing endocrine secretory pathways in salivary glands for systemic gene therapeutics. J. Cell. Physiol. 199, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Adriaansen J., Perez P., Zheng C., Collins M. T., Baum B. J. (2011) Human parathyroid hormone is secreted primarily into the bloodstream after rat parotid gland gene transfer. Hum. Gene Ther. 22, 84–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Acosta A., Hurtado M. D., Gorbatyuk O., La Sala M., Duncan D., Aslanidi G., Campbell-Thompson M., Zhang L., Herzog H., Voutetakis A., Baum B. J., Zolotukhin S. (2011) Salivary PYY: a putative bypass to satiety. PloS One 6, e26137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zheng C., Shinomiya T., Goldsmith C. M., Di Pasquale G., Baum B. J. (2011) Convenient and reproducible in vivo gene transfer to mouse parotid glands. Oral Dis. 17, 77–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Voutetakis A., Zheng C., Cotrim A. P., Mineshiba F., Afione S., Roescher N., Swaim W. D., Metzger M., Eckhaus M. A., Donahue R. E., Dunbar C. E., Chiorini J. A., Baum B. J. (2010) AAV5-mediated gene transfer to the parotid glands of non-human primates. Gene Ther. 17, 50–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Voutetakis A., Zheng C., Metzger M., Cotrim A. P., Donahue R. E., Dunbar C. E., Baum B. J. (2008) Sorting of transgenic secretory proteins in rhesus macaque parotid glands after adenovirus-mediated gene transfer. Hum. Gene Ther. 19, 1401–1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zheng C., Nikolov N. P., Alevizos I., Cotrim A. P., Liu S., McCullagh L., Chiorini J. A., Illei G. G., Baum B. J. (2010) Transient detection of E1-containing adenovirus in saliva after the delivery of a first-generation adenoviral vector to human parotid gland. J. Gene Med. 12, 3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.