Abstract

Substrate-level phosphorylation mediated by succinyl-CoA ligase in the mitochondrial matrix produces high-energy phosphates in the absence of oxidative phosphorylation. Furthermore, when the electron transport chain is dysfunctional, provision of succinyl-CoA by the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (KGDHC) is crucial for maintaining the function of succinyl-CoA ligase yielding ATP, preventing the adenine nucleotide translocase from reversing. We addressed the source of the NAD+ supply for KGDHC under anoxic conditions and inhibition of complex I. Using pharmacologic tools and specific substrates and by examining tissues from pigeon liver exhibiting no diaphorase activity, we showed that mitochondrial diaphorases in the mouse liver contribute up to 81% to the NAD+ pool during respiratory inhibition. Under these conditions, KGDHC's function, essential for the provision of succinyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA ligase, is supported by NAD+ derived from diaphorases. Through this process, diaphorases contribute to the maintenance of substrate-level phosphorylation during respiratory inhibition, which is manifested in the forward operation of adenine nucleotide translocase. Finally, we show that reoxidation of the reducible substrates for the diaphorases is mediated by complex III of the respiratory chain.—Kiss, G., Konrad, C., Pour-Ghaz, I., Mansour, J. J., Németh, B., Starkov, A. A., Adam-Vizi, V., Chinopoulos, C. Mitochondrial diaphorases as NAD+ donors to segments of the citric acid cycle that support substrate-level phosphorylation yielding ATP during respiratory inhibition.

Keywords: succinyl-CoA ligase, adenine nucleotide translocase, DT-diaphorase, reducing equivalent

In the absence of oxygen or when the electron transport chain is impaired, substrate-level phosphorylation in the matrix is the only means for production of high-energy phosphates in mitochondria. Mitochondrial substrate-level phosphorylation is almost exclusively attributable to succinyl-CoA ligase, an enzyme of the citric acid cycle that catalyzes the reversible conversion of succinyl-CoA and ADP (or GDP) to CoASH, succinate, and ATP (or GTP) (1). We have shown previously that when the electron transport chain is compromised and F0–F1 ATP synthase reverses, pumping protons out of the matrix at the expense of ATP hydrolysis, the mitochondrial membrane potential is maintained, albeit at decreased levels, for as long as matrix substrate-level phosphorylation is operational, without a concomitant reversal of the adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT; ref. 2). This process prevents mitochondria from becoming cytosolic ATP consumers (3–5). More recently, we have reported that provision of succinyl-CoA by the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (KGDHC) in respiration-impaired mitochondria is critical to sustaining the succinyl-CoA ligase reaction (6). Mindful of the reaction catalyzed by KGDHC converting α-ketoglutarate, CoASH, and NAD+ to succinyl-CoA, NADH, and CO2, the question arises as to the source of NAD+, under conditions of a dysfunctional electron transport chain. It is common knowledge that NADH generated in the citric acid cycle is oxidized by complex I, resupplying NAD+ to the cycle. In the absence of oxygen or when complexes are not functional, an excess of NADH in the matrix is expected. Yet, our previous reports showed that without NADH oxidation by complex I of the respiratory chain, substrate-level phosphorylation is operational and supported by succinyl-CoA (2, 6), implying KGDHC activity. In the present study we found that during anoxia or pharmacologic blockade of complex I, mitochondrial diaphorases oxidized matrix NADH supplying NAD+ to KGDHC, which in turn yields succinyl-CoA, thus supporting substrate-level phosphorylation.

In general, diaphorase activity is attributed to a flavoenzyme catalyzing the oxidation of reduced pyridine nucleotides by endogenous or artificial electron acceptors called DT-diaphorase because of its reactivity with both DPNH (NADH) and TPNH (NADPH), identified by Lars Ernster (7, 8), and is now known as NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO). It has also been identified in parallel by Märki and Martius (9), called vitamin K reductase, and later confirmed to be the same enzyme (10). A quinone reductase with properties similar to the enzyme described by Ernster also appears in earlier literature by Wosilait and colleagues (11, 12), as well as the microsomal TPNH-neotetrazolium diaphorase, described by Williams et al. (13), and a brain diaphorase by Giuditta and Strecker (14, 15). Finally, a vitamin K3 (menadione) reductase has been reported by Koli et al. (16). DT-diaphorase (EC 1.6.5.2, formerly assigned to EC 1.6.99.2) catalyzes 2-electron reductive metabolism [unlike other NAD(P)–linked quinone reductases; ref. 17] detoxifying quinones and their derivatives (18). Several isoforms have been identified (19, 20); among them, NQO1 and NQO2 have been most extensively characterized (19). A striking difference between these two is that NQO2 uses dihydronicotinamide riboside (NRH), while NQO1 uses NAD(P)H as an electron donor (21, 22). NQO1 has been found to localize, not only in the cytosol, but also in mitochondria from several tissues (10, 23–33). Mitochondrial diaphorase corresponds to 3–15% of total cellular activity (10, 28, 31–34) and is localized in the matrix, since it reacts only with intramitochondrial reduced pyridine nucleotides, but is inaccessible to those added from the outside (30, 35). However, it must be emphasized that mitochondrial diaphorase activity may not be exclusively due to NQO1. Other mitochondrial enzymes also exhibit diaphorase-like activity as a moonlighting function; for example, the isolated DLD subunit of KGDHC exhibits diaphorase activity, and it is known to exist in the matrix as such, without being part of the KGDHC (36–41).

Finally, we scrutinized the pathway responsible for providing oxidized substrates to the diaphorases and concluded that reoxidation is mediated by complex III of the respiratory chain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Mice were of mixed FVB and C57Bl/6 background, only C57Bl/6J, or only C57Bl/6N, as indicated throughout the text. NADH:cytochrome b5 reductase isoform 2 (Cyb5r2) heterozygous mice on a C57BL/6 background were obtained from the European Mouse Mutant Archive (EMMA) node at the Medical Research Council (MRC)-Harwell (Harwell, UK) and the European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program (EUCOMM) consortium. They were backcrossed for ≥5 generations with FVB mice, yielding wild-type (WT), heterozygous, and viable fertile homozygous knockout (KO) Cyb5r2−/− mice. The animals used in our study were of either sex and between 2 and 3 mo of age. They were housed in a room maintained at 20–22°C on a 12-h light-dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. Pigeons (Columba livia domestica) were obtained from a local vendor and used on the same or the next day. All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Semmelweis University (Egyetemi Állatkísérleti Bizottság).

Isolation of mitochondria

Liver mitochondria from all animals were isolated according to a published method (42). Protein concentration was determined with the bicinchoninic acid assay and calibrated with bovine serum standards (43), with a Tecan Infinite 200 PRO series plate reader (Tecan Deutschland GmbH, Crailsheim, Germany). Yields were typically 0.4 ml from ∼80 mg/ml per mouse liver and 0.8 ml from ∼80 mg/ml per pigeon liver.

Determination of membrane potential (ΔΨm) in isolated liver mitochondria

ΔΨm of isolated mitochondria (1 mg for mouse or pigeon liver per 2 ml of medium, unless stated otherwise) was estimated fluorometrically with safranin O (44). Traces obtained from mouse mitochondria were calibrated to millivolts (2). Fluorescence was recorded in a Hitachi F-7000 spectrofluorometer (Hitachi High Technologies, Maidenhead, UK) at a 5-Hz acquisition rate, with 495- and 585-nm excitation and emission wavelengths, or at a 1-Hz rate, with the O2k-fluorescence LED2 module of the Oxygraph-2k (Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria), equipped with an LED exhibiting a wavelength maximum of 465 ± 25 nm (current for light intensity adjusted to 2 mA, i.e., level 4) and a <505-nm shortpass excitation filter (dye-based, safranin filter set). Emitted light was detected by a photodiode (range of sensitivity: 350–700 nm), through a >560-nm longpass emission filter (dye-based). Experiments were performed at 37°C. ΔΨm was also estimated from tetraphenylphosphonium (TPP+) ion distribution with a custom-made TPP+-selective electrode (45). For these experiments, the assay medium (identical to that for safranin O experiments) was supplemented with 2 μM TPP+Cl−, and the mitochondrial protein concentration was 2 mg/ml. The electrode was calibrated by sequential additions of TPP+Cl−. Experiments were performed at 37°C.

Mitochondrial respiration

Oxygen consumption was performed polarographically with the Oxygraph-2k. Liver mitochondria (2 mg) was suspended in 4 ml incubation medium, the composition of which was identical to that for ΔΨm determination (2). Experiments were performed at 37°C. Oxygen concentration and oxygen flux (expressed in picomoles per second per milligram and calculated as the negative time derivative of oxygen concentration, divided by mitochondrial mass per volume and corrected for instrumental background oxygen flux arising from oxygen consumption of the oxygen sensor and back diffusion into the chamber) were recorded with DatLab software (Oroboros Instruments).

Determination of pH of the medium

The pH of the suspension medium for mouse liver mitochondria was recorded by connecting a glass Ag/AgCl pH microelectrode (Radiometer Analytical, Lyon, France) to the potentiometric channel of the O2k via a BNC connector of the Oxygraph-2k. The composition of this medium was 120 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM mannitol, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Pi, 0.01 mM EGTA (K+ salt), 0.01 mM P1,P5-di(adenosine-5′) pentaphosphate (pH 7.25; titrated with KOH), and 0.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA). Experiments were performed at 37°C. The voltage signal output of the electrode was converted to pH by calibrating with solutions of known pH values.

Determination of NADH autofluorescence in isolated liver mitochondria

NADH autofluorescence was measured using 340- and 435-nm excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively. Measurements were performed in a Hitachi F-7000 fluorescence spectrophotometer at a 5-Hz acquisition rate. Mouse liver mitochondria (1 mg) were suspended in 2 ml incubation medium, the composition of which was the following: 110 mM K-gluconate, 10 mM HEPES (acid free), 10 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM mannitol, 10 mM NaCl, 8 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.01 mM EGTA, 0.5 mg/ml BSA (essentially fatty acid free), with the pH adjusted to 7.25 with KOH. Respiratory substrates were 5 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate. Experiments were performed at 37°C.

Statistics

Data are presented as averages ± se. Significant differences between 2 groups were evaluated by Student's t test. Significant differences between ≥3 groups were evaluated by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. If the normality test failed, ANOVA on ranks was performed. Wherever single graphs are presented, they are representative of ≥3 independent experiments.

Reagents

Standard laboratory chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Gallen, Switzerland); tyrphostin-9,RG-50872,malonaben,3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzylidenemalononitrile,2,6-di-t-butyl-4-(2′,2′-dicyanovinyl)phenol (SF 6847) and atpenin A5 were from Enzo Life Sciences (ELS AG, Lausen, Switzerland); carboxyatractyloside (cATR) was from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), and MitoQ was a generous gift from Dr. Mike Murphy (Mitochondrial Biology Unit, Medical Research Council, Cambridge, UK). Mitochondrial substrate stock solutions were dissolved in bidistilled water and titrated to pH 7.0 with KOH. ADP was purchased as a K+ salt of the highest purity available (Merck) and titrated to pH 6.9.

RESULTS

Identifying mitochondria as extramitochondrial ATP consumers during anoxia

As elaborated in our prior work (2, 6), to label a mitochondrion as an extramitochondrial ATP consumer, its ΔΨm, matrix ATP/ADP ratio, and reversal potentials of F0–F1 ATP synthase and ANT (the ΔΨm values at which there is no ATP generation or hydrolysis for the former and no net transfer of ADP-ATP across the inner mitochondrial membrane for the latter) must be determined, which is an extremely challenging experimental undertaking. Being mindful that the reversal potential of the F0–F1 ATP synthase is more negative than that of the ANT (2, 4, 5), meaning that whenever the ANT reverses, the ATP synthase works in reverse, too, it is simpler and equally informative to examine the effect of an ANT inhibitor on ΔΨm during ADP-induced respiration (2, 4, 5). Since 1 molecule of ATP4− is exchanged for 1 molecule of ADP3− (both nucleotides being Mg2+ free and deprotonated) by ANT, the exchange is electrogenic (46). Therefore, during the forward mode of ANT, abolition of its operation by a specific inhibitor such as cATR leads to an increase in ΔΨm, whereas during the reverse mode of ANT, the same condition leads to a loss of ΔΨm. This biosensor test (i.e., the effect of cATR on safranin O fluorescence reflecting ΔΨm) was successfully used in addressing the directionality of ANT during respiratory inhibition (2). Further on, it was used in KGDHC-deficient mice (6) to determine the contribution of KGDHC as a succinyl-CoA provider to the succinyl CoA ligase reaction during respiratory inhibition. In the present study, we used this method in isolated mitochondria subjected to true anoxic conditions and/or specific inhibitors of the electron transport chain, while sources of NAD+ for KGDHC were being sought.

Time-lapse recordings of safranin O fluorescence reflecting ΔΨm while measuring oxygen concentration in the same sample were obtained by the recently developed O2k-fluorescence LED2 module of the Oxygraph-2k (Oroboros Instruments). Mitochondria were allowed to deplete the oxygen dissolved in the air-sealed chamber and, additions of chemicals through a tiny bore hole did not allow reoxygenation of the buffer from the ambient atmosphere.

Safranin O is known to increase state 4 respiration (47), decrease maximum Ca2+ uptake capacity, and exhibit an appreciable nonspecific binding component, if used at concentrations above 5 μM (48). However, at concentrations below 5 μM, calibration of the safranin O fluorescence signal to ΔΨm deviates significantly from linearity; therefore, more complex fitting functions are needed, decreasing the faithfulness of the conversion. For our experiments, we used 5 μM of safranin O at the expense of diminishing the respiratory control ratio by approximately 1 unit (from 7.5 to 6.5, when using glutamate and malate), but the signal-to-noise ratio was optimal, and the calibration of the fluorescence signal to ΔΨm was highly reproducible. TPP+ appeared to be less toxic than safranin O in terms of an effect on mitochondrial respiration; however, the signal-to-noise ratio was not as satisfactory as that obtained from safranin O, and it could not be improved by increasing the concentration of TPP+ (from 2 to 6 μM). The nonspecific binding component of safranin O to mitochondria is determined by the mitochondria/safranin O ratio; by using 5 μM of safranin O for 2 mg of mitochondria (see below) the nonspecific component is within 10% of the total safranin O fluorescence signal, estimated by the increase in fluorescence caused by the addition of a detergent to completely depolarized mitochondria (not shown). As such, it was accounted for, during the calibration of the fluorescence signal to ΔΨm.

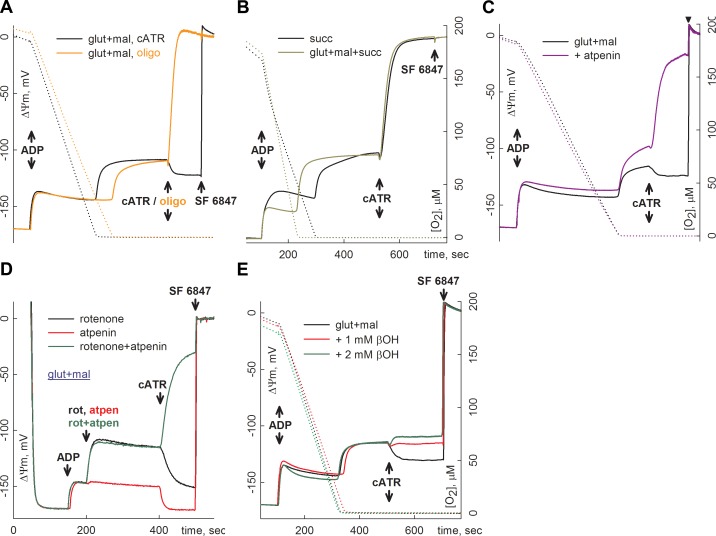

The result of a typical experiment is shown in Fig. 1. Mouse liver mitochondria (2 mg) were added to 4 ml of buffer (see Materials and Methods) containing the substrates indicated in the panels and were allowed to fully polarize (solid traces). State 3 respiration was initiated by ADP (2 mM), depolarizing mitochondria by ∼25 mV. With a respiration rate of ∼60 nmol/min/mg, mitochondria run out of oxygen within 5–6 min, as verified by recording 0 levels of dissolved oxygen in the chamber at ∼400 s (dotted traces). Anoxia also coincided with the onset of additional depolarization, leading to a clamp of ΔΨm at ∼−100 mV. In mitochondria respiring on glutamate and malate (i.e., substrates that support substrate-level phosphorylation; ref. 2), subsequent addition of cATR (Fig. 1A, black solid trace) caused moderate repolarization. This observation implies that, at ∼−100 mV, ANT was still operating in the forward mode, in accordance with the ADP-ATP steady-state exchange activity/ΔΨm relationship shown recently (49, 50). In contrast, when the specific F0–F1 ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin (Fig. 1A, orange solid trace) was added instead of cATR, immediate depolarization was observed, implying that F0–F1 ATP synthase was working in reverse and generated the residual ΔΨm. This depolarization was complete, since further addition of the uncoupler SF 6847 (250 nM) yielded no further depolarization. Obviously, under the conditions shown in Fig. 1A, ATP was available in the matrix from sources other than ANT. Our previous results showed (2, 6) that under this condition, ATP is supplied by matrix substrate-level phosphorylation mediated by succinyl-CoA ligase. This finding was further validated by the experiments shown in Fig. 1B, C. In Fig. 1B, mitochondria respiring on succinate alone (black trace) or glutamate plus malate plus succinate (olive green trace), both conditions being unfavorable for substrate-level phosphorylation by succinyl-CoA ligase (succinate would push this reversible reaction toward ATP or GTP hydrolysis), reacted to cATR with an immediate and complete depolarization in anoxia. Likewise, in the presence of 2 μM atpenin A5, a specific inhibitor of succinate dehydrogenase (51) causing accumulation of succinate in the matrix, cATR induced depolarization in mitochondria that had been respiring on glutamate plus malate and were subject to anoxia (Fig. 1C, lilac trace). In the presence of atpenin, however, onset of anoxia was associated with a greater depolarization before addition of cATR; thus, it is possible that the value of ΔΨm exceeded the value of the reversal potential of ANT (Erev[lowem]ANT). However, when the electron transport chain was rendered inoperable by rotenone in lieu of anoxia, ΔΨm values were identical before addition of the ANT inhibitor (Fig. 1D, compare black with green trace), but loss of ΔΨm, implying ANT reversal in the presence of atpenin A5, was verified by cATR.

Figure 1.

Reconstructed time courses of safranin O signal calibrated to ΔΨm (solid traces) and parallel measurements of oxygen concentration in the medium (dotted traces) in isolated mouse liver mitochondria. Effect of cATR (2 μM) or oligomycin (oligo, 5 μM) on ΔΨm during anoxia (A–C, E) or during compromised respiratory chain by poisons (D), in the presence of different substrate combinations. ADP (2 mM) was added where indicated. Substrate concentrations were glutamate (glut; 5 mM), malate (mal; 5 mM), succinate (succ; 5 mM), and β-hydroxybutyrate, (βOH; 1 or 2 mM, as indicated). Substrate concentrations were the same for all subsequent experiments. At the end of each experiment, 1 μM SF 6847 was added to achieve complete depolarization, except for the orange trace in panel A, where 250 nM SF 6847 was added.

From the findings in those experiments, we concluded that, in true anoxic conditions, ANT could be maintained in forward mode, implying active matrix substrate-level phosphorylation in isolated mitochondria, similar to the previously published paradigms with a poisoned respiratory chain (2, 6). Furthermore, the results obtained in our earlier study (6) showing that provision of succinyl-CoA by KGDHC is critical for matrix substrate-level phosphorylation imply an emerging demand of NAD+ for KGDHC, a concept that is at odds with the idea that, in anoxia, there is a shortage of NAD+ in the mitochondrial matrix. Indeed, Fig. 1E shows that after elevating the matrix NADH/NAD+ ratio by 1 or 2 mM β-hydroxybutyrate (leading to NADH and acetoacetate formation through the reaction catalyzed by β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase), cATR induced slight depolarization, compared to near repolarization in Fig. 1A, C, E (black traces). The same effect of β-hydroxybutyrate was found in mitochondria with a poisoned respiratory chain (6). These results emphasize the importance of NAD+ for establishing the conditions for the forward operation of ANT during anoxia.

Importance of NAD+ in maintaining the function of KGDHC during anoxia or respiratory chain inhibition

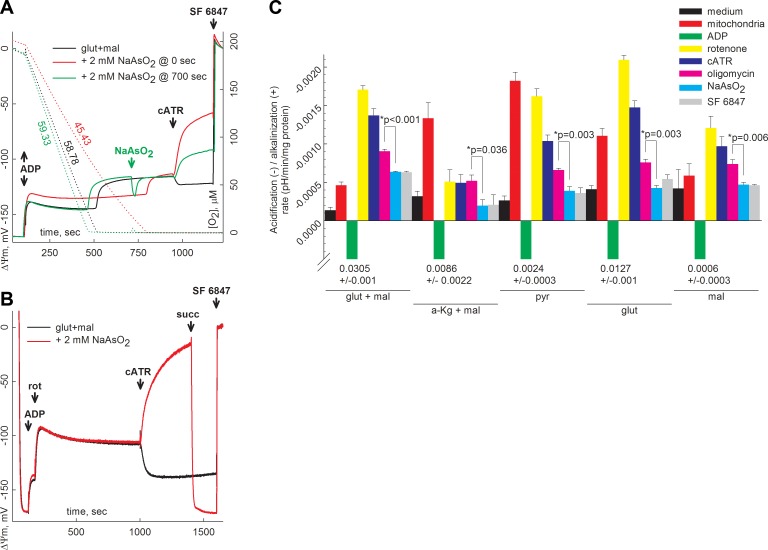

The negative effect of KGDHC deficiency on matrix substrate-level phosphorylation in mitochondria with a poisoned respiratory chain has been demonstrated recently by our group (6). In the present study, we addressed the importance of sustaining KGDHC function, requiring a supply of NAD+ in mitochondria during anoxia by using arsenite, which enters intact mitochondria in an energy-dependent manner (52) and inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHC) and KGDHC (53). When mitochondria respire on glutamate plus malate, the effect of arsenite may be attributable to inhibition of KGDHC. Safranin O fluorescence and oxygen concentration in the medium where mitochondria underwent anoxia or drug-induced respiratory inhibition were recorded. As shown in Fig. 2A, the fully polarized mitochondria, in the presence of glutamate and malate, were depolarized by ∼25 mV by ADP (2 mM, solid black and green traces), consuming within ∼6 min the total amount of oxygen present in the medium (dotted black and green traces) and leading to additional depolarization to ∼−100 mV. Respiration rates are indicated in the figure, in nanomoles per minute per milligram protein (Fig. 2A). The transient repolarization on addition of 2 mM sodium arsenite (NaAsO2) at 700 s was due to the high volume of the addition (0.08 ml), which contained a significant amount of dissolved oxygen, seen as a minor elevation in oxygen concentration (Fig. 2A, dotted green line near 700 s) that quickly subsided as it was consumed by the mitochondria; it was also associated with the reestablishment of ΔΨm to ∼−100 mV. Subsequent addition of cATR to mitochondria treated with NaAsO2 (Fig. 2A, green solid trace) initiated a drop in ΔΨm as opposed to a moderate repolarization observed in the absence of arsenite (Fig. 2A, black solid trace). cATR also caused a depolarization when arsenite was present in the medium before addition of mitochondria (Fig. 2A, red solid trace), which, as expected, was associated with a diminished rate of respiration (Fig. 2A, red dotted trace) leading to a prolongation until complete anoxia was achieved. cATR also caused a depolarization when arsenite was present in the medium before mitochondria (Fig. 2B, red trace), in which electron transport was halted by inhibiting complex I with rotenone. Subsequent addition of succinate (5 mM) fully restored ΔΨm, indicating that mitochondria were capable of electron transport from complex II when complex I was blocked, in the presence of arsenite. Finally, the effect of arsenite was investigated on the rate of acidification in weakly buffered media, in which mitochondria were treated with a specific set of inhibitors. The concept of this experiment relies on the fact that mitochondria are net CO2 producers that acidify the medium due to the following equilibria: CO2 + H2O ↔ H2CO3 ↔ H+ + HCO3−. Depending on the substrates combined with targeted inhibition of bioenergetic entities, one may deduce the role of arsenite-inhibitable targets. Mitochondria were suspended in a weakly buffered medium (see Materials and Methods) containing the substrates shown in Fig. 2C. Bars above the x axis in Fig. 2C indicate acidification; those below indicate alkalinization. The sequence of additions (see Fig. 2C) was as follows: medium (black), mitochondria (2 mg, red), ADP (2 mM, green), rotenone (1 μM, yellow), cATR (2 μM, blue), oligomycin (5 μM, magenta), NaAsO2 (2 mM, cyan), and SF 6847 (1 μM, gray). With substrate combinations bypassing PDHC (glutamate plus malate, α-ketoglutarate plus malate, or glutamate alone; all at 5 mM) arsenite caused a statistically significant decrease in acidification in mitochondria pretreated with rotenone, cATR, and oligomycin. We assumed that, in mitochondria in which complex I is blocked by rotenone, ANT and F0–F1 ATP synthase are blocked by cATR and oligomycin, respectively, the arsenite-inhibitable acidification may only stem from KGDHC generating CO2. The CO2 production by KGDHC in respiration-impaired mitochondria suggests the availability of NAD+. Mindful of these results, we sought NAD+ sources in mitochondria other than that produced by complex I and considered the possibility of NAD+ provision by mitochondrial diaphorases.

Figure 2.

A) Reconstructed time courses of safranin O signal calibrated to ΔΨm (solid traces) and parallel measurements of oxygen concentration in the medium (dotted traces) in isolated mouse liver mitochondria. Effect of cATR (2 μM) on ΔΨm of mitochondria during anoxia in the presence or absence of 2 mM NaAsO2 is shown. ADP (2 mM) was added where indicated. Respiration rates in nanomoles per minute per milligram protein are indicated on the dotted lines. B) Reconstructed time courses of safranin O signal calibrated to ΔΨm in isolated mouse liver mitochondria in an open chamber. Effect of cATR (2 μM) on ΔΨm of mitochondria treated with rotenone (rot; 1 μM, where indicated) in the presence or absence of 2 mM NaASO2 (2 mM, red trace) is shown. ADP (2 mM) was added where indicated. At the end of each experiment, 1 μM SF 6847 was added to achieve complete depolarization. C) Rates of acidification in the suspending medium of mitochondria respiring on the various substrate combinations indicated, on addition of different bioenergetic poisons. a-Kg, α-ketoglutarate; glut, glutamate; mal, maleate; pyr, pyruvate; succ, succinate.

Effect of diaphorase inhibitors on bioenergetic parameters

As mentioned, diaphorase activity is attributable to flavoproteins designated NQOs (18). Depending on the organism, several isoforms and their polymorphisms have been identified (reviewed in refs. 19, 20). Among these, NQO1 and NQO2 have been most extensively characterized (19). Although NQO1 is not in the list of mouse or human mitochondrial proteins (MitoCarta; ref. 54) and may not localize in mitochondria of certain human cancers (55), it has been found in mitochondria from different tissues (23–25). To address the contribution of mitochondrial diaphorases to provision of NAD+ for the KGDHC reaction in anoxia, we used an array of pharmacologic inhibitors; however, all of them exhibit uncoupling properties at high concentrations (29, 56). The potential uncoupling effect of an inhibitor would be confounding, because, in its presence, ΔΨm could become less negative than Erev_ANT, leading to ANT reversal (2). In this case, its effect could not be distinguished from a genuine effect on the diaphorases. Therefore, we first determined the concentration range in which their uncoupling effects were negligible. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S1, the dose-dependent effects of 4 different NQO1 inhibitors—chrysin, 7,8-dihydroxyflavone hydrate (diOH-flavone), phenindione, and dicoumarol—were compared to that of a vehicle (Supplemental Fig. S1, black bars) on ΔΨm in mitochondria respiring on glutamate and malate (Supplemental Fig. S1A), after addition of 2 mM ADP (Supplemental Fig. S1B) and after the addition of cATR (Supplemental Fig. S1C), while simultaneously, in the same samples, rates of oxygen consumption were recorded (Supplemental Fig. S1D–F, for states 2, 3, and 4c, respectively, induced by cATR). Supplemental Fig. S1 shows the effects of 8 consecutive additions of chrysin, (2.5 μM each, red bars); diOH-flavone (5 μM each, green bars); phenindione (2.5 μM each, yellow bars), and dicoumarol (1.25 μM each, blue bars). From the bar graphs in Supplemental Fig. S1, it is apparent that all diaphorase inhibitors exhibited a concentration range in which they had no significant uncoupling effect (for chrysin, ≤5 μM, for phenindione, ≤20 μM, and for dicoumarol, ≤5 μM). DiOH-flavone showed a significant quenching effect on the safranin O signal during state 3 respiration; thus, only its effect on oxygen consumption rate was evaluated to establish the safe use at a concentration below 20 μM. Finally, the effect of diaphorase inhibitors was compared to that of the uncoupler SF 6847 in decreasing NADH signals in intact isolated mitochondria. Such an experiment (for dicoumarol) is demonstrated in Supplemental Fig. S1G, H. Mouse liver mitochondria (1 mg) were allowed to fully polarize in medium (detailed in Materials and Methods) containing glutamate and malate. Then, vehicle (control), 1.25 μM dicoumarol, or 10 nM SF 6847 was added. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S1G, while SF 6847 dose dependently decreased NADH fluorescence, 1.25–5 μM dicoumarol was without effect. The changes in NADH fluorescence shown in Supplemental Fig. S1G were largely controlled by complex I, because in the presence of rotenone (Supplemental Fig. S1H), responses to dicoumarol and SF 6847 were almost completely dampened.

Effect of diaphorase inhibitors on ANT directionality in anoxic or rotenone-treated mitochondria

Having established the concentration range of the diaphorase inhibitors exhibiting no appreciable uncoupling activity, we wanted to determine their effects in the biosensor test, which addresses the direction of the operation of ANT by recording the effect of cATR on ΔΨm in respiration-impaired mitochondria, when they are exquisitely dependent on matrix substrate-level phosphorylation (2). The rationale behind these experiments was that diaphorases may be responsible for providing NAD+ to KGDHC, which, in turn, is important for generating succinyl CoA for substrate-level phosphorylation. The experimental conditions in Fig. 3A–D were essentially similar to those shown in Fig. 1, again demonstrating changes in ΔΨm in response to cATR. The anoxia also coincided with the onset of depolarization, leading to a clamp of ΔΨm to ∼−100 mV. As shown in Fig. 3A–D (black solid traces), addition of cATR in mitochondria made anoxic caused a repolarization, implying a forward operation of ANT, despite the lack of oxygen. However, in the presence of diaphorase inhibitors (concentration and color-coding detailed in Fig. 3A), cATR induced depolarization (solid traces) without affecting the rate of respiration (Fig. 3A–D, dotted traces), implying ANT reversal. Likewise, in the presence of diaphorase inhibitors (concentration and color-coding detailed in Fig. 3E), rotenone-treated mitochondria (Fig. 3E–H, red and orange traces) responded to cATR with depolarization, as compared to their vehicles showing cATR-induced repolarizations (Fig. 3E–H, black and gray traces). From these results, we concluded that diaphorases are likely to provide NAD+ to KGDHC that, in turn, support substrate-level phosphorylation via generating succinyl-CoA during anoxia or inhibition of complex I by rotenone.

Figure 3.

Reconstructed time courses of safranin O signal calibrated to ΔΨm (solid traces) and parallel measurements of oxygen concentration in the medium (dotted traces) in isolated mouse liver mitochondria supported by glutamate and malate. Effect of diaphorase inhibitors (doses are color-coded in panel A) on cATR-induced changes in ΔΨm during anoxia (A–D) or under complex I inhibition by rotenone (E–H). Gray traces in panels E–H show the effect of vehicles (either DMSO or ethanol). At the end of each experiment, 1 μM SF 6847 was added to achieve complete depolarization.

To quasi-quantify the extent of contribution of NAD+ emanating from the mitochondrial diaphorases that can be utilized by KGDHC during anoxia, we compared the rates of cATR-induced depolarizations (in millivolts per second) in the presence of diaphorase inhibitors to the rate of cATR-induced depolarization in the presence of 2 mM NaAsO2. From the data obtained with 20 μM diOH-flavone, 5 μM dicoumarol, 5 μM chrysin, and 20 μM phenindione, we inferred that mitochondrial diaphorases contributed 26, 41, 37 and 81%, respectively, to the matrix NAD+ pool during anoxia.

Effect of diaphorase substrates on ANT directionality of respiration-impaired mitochondria due to anoxia or rotenone

To strengthen our conclusion, we next performed the biosensor test in the presence of known diaphorase substrates in mitochondria undergoing respiratory inhibition by anoxia or rotenone. Diaphorase activity mediated by NQO1 exhibits lack of substrate and electron donor specificity because its active site can accommodate molecules of various size and structure (57, 58); therefore, various types of quinoid compounds and their derivatives can be processed by the isolated enzyme (59). Furthermore, it is able to react with different dyes, nitro compounds, and some inorganic substances (60). The mitochondrial matrix is a quinone-rich environment, containing several coenzyme Qs (CoQs) with variable side chains. Of course, NQO1 exhibits unequal affinities for them, but it is reasonable to assume that some CoQs are in the millimolar concentration range and could be substrates for NQO1. We tested 14 different diaphorase substrates: menadione (10 μM), vitamin K1 (phylloquinone; 10 μM), vitamin K2 (menaquinone; 10 μM), duroquinone (DQ; 10–100 μM), mitoquinone (mitoQ; 0.5 μM), p-benzoquinone (BQ; 10 μM), methyl-p-benzoquinone (MBQ; 10 μM), 2,6-dimethylbenzoquinone (DMBQ; 10–50 μM), 2-chloro-1,4-benzoquinone (CBQ; 10 μM), 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (DCBQ; 10 μM), 1,2-naphthoquinone (1.2-NQ; 10 μM), 1,4-naphthoquinone (1.4-NQ; 10 μM), 2,6-dichloroindophenol (DCIP; 50 μM), and 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5,7-trihydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one (quercetin; 10 μM). In concentrations exhibiting no uncoupling or other side effects on ΔΨm or rate of respiration (not shown), mouse liver mitochondria were treated with ADP and cATR, similar to that demonstrated in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 4A–C and Supplemental Fig. S2, when using different substrate combinations supporting respiration, addition of cATR caused repolarization, except when glutamate plus malate plus β-hydroxybutyrate were used (Fig. 4C, black solid trace), a substrate combination that, as discussed earlier, limits the availability of NAD+ during anoxic conditions. In this paradigm, dose-dependent addition of DQ during anoxia led to cATR-induced repolarization (Fig. 4C, colored solid traces). Addition of menadione had no effect (Fig. 4A, solid orange trace), whereas mitoQ even abolished the cATR-induced repolarization (Fig. 4B, solid green trace). By contrast, when respiratory inhibition was achieved by rotenone instead of anoxia, DQ, menadione, and mitoQ resulted in a strong cATR-induced repolarization (Fig. 4D–H). This effect of menadione was not shared by phylloquinone and menaquinone, as shown in Fig. 4G, H. The variable effects of a host of other quinones in this paradigm are shown in Supplemental Fig. S2. Furthermore, since safranin O may also be a substrate for diaphorases due to its structural similarity to Janus green B, which is a genuine diaphorase substrate (60), redistribution of TPP as an index of ΔΨm was also measured as an alternative, by using a TPP electrode, (Fig. 4I). Mitochondria were allowed to polarize from glutamate and malate, then ADP (2 mM) was added, followed by rotenone, which led to depolarization. Addition of cATR induced repolarization, as in the above experiment, indicating that safranin O is unlikely to be a diaphorase substrate. From these results, we concluded that mitochondrial diaphorases are not saturated by endogenous quinones and most likely provide NAD+ to KGDHC, which, in turn, yields succinyl-CoA, supporting substrate-level phosphorylation during anoxia or inhibition of complex I by rotenone. Furthermore, there appeared to be a clear distinction between true anoxia and rotenone-induced respiratory inhibition; in anoxia, menadione and mitoQ were not effective in conferring cATR-induced repolarization. The reasons for this were investigated further in the experiments outlined below.

Figure 4.

A–H) Reconstructed time courses of safranin O signal calibrated to ΔΨm (solid traces) and parallel measurements of oxygen concentration in the medium (dotted traces) in isolated mouse liver mitochondria, demonstrating the effect of diaphorase substrates on cATR-induced changes in ΔΨm during anoxia (A–C) or complex I inhibition by rotenone (rot; D–H). Substrate combinations are indicated in the panels. I) Reconstructed time course of TPP signal (in volts) in isolated mouse liver mitochondria (mitos) supported by glutamate (glut) and malate (mal). Additions were as indicated by arrows. α-Kg, α-ketoglutarate; βOH, β-hydroxybutyrate. At the end of each experiment, 1 μM SF 6847 was added to achieve complete depolarization.

Role of complex III in reoxidizing diaphorase substrates

To address the discrepancy that emerged from the results obtained with rotenone-treated vs. anoxia-treated mitochondria, with respect to the effect of diaphorase substrates, we inhibited mitochondrial respiration with stigmatellin, a specific inhibitor of complex III. The rationale behind the use of this inhibitor came from several reports pointing to complex b of complex III as being capable of reoxidizing substrates that are reduced by mitochondrial diaphorases (29, 32, 61–64). As shown in Fig. 5A–D, in mouse liver mitochondria respiring on the different substrate combinations indicated in the panels, state 3 respiration initiated by ADP (2 mM) was arrested by 0.8 μM stigmatellin, leading to a clamp of ΔΨm to ∼−100 mV. Subsequent addition of cATR (Fig. 5A–C, black solid traces) conferred depolarization to a variable extent, depending on the substrates used, indicating that functional complex III is necessary for the forward operation of ANT when it relies on ATP generated by substrate-level phosphorylation. The lack of reoxidation of the reduced diaphorase substrate by complex III is likely to reflect in the result (see below), showing that the presence of menadione (Fig. 5A–C, red traces) or mitoQ (Fig. 5D, lilac trace), but not DQ (Fig. 5D, green trace), conferred a more robust cATR-induced depolarization. In mitochondria undergoing respiratory arrest by anoxia (Fig. 5E), addition of stigmatellin (olive green trace) did not result in cATR-induced depolarization. However, while respiratory arrest of mitochondria achieved by inhibiting complex IV with KCN (1 mM) yielded a very small change in ΔΨm by cATR (Fig. 5F, green trace), the copresence of ferricyanide, K3[Fe(CN)6] (FerrCyan; 1 mM), which can oxidize cytochrome c because of its higher redox potential (∼400 vs. 247–264 mV for cytochrome c, depending on various factors; refs. 65, 66) led to cATR-induced repolarization (Fig. 5F, gray trace). This effect was abolished by stigmatellin (Fig. 5F, orange trace). When FerrCyan was used, it was necessary to titrate ΔΨm back to the same levels as in its absence; hence, SF 6847 (5 nM boluses) was added where indicated (Fig. 5F, gray trace). From these experiments, we concluded that stigmatellin negates the beneficial effect of diaphorase substrates that assist in cATR-induced repolarization, emphasizing the involvement of complex III in mitochondria with respiratory inhibition by rotenone or anoxia.

Figure 5.

Effect of the diaphorase substrates menadione (10 μM; A–C), DQ (50 μM; D) and mitoQ (0.5 μM; D), on cATR-induced changes of ΔΨm after complex III inhibition by stigmatellin (stigma; E) or complex IV by KCN (F). Reconstructed time courses of safranin O signal calibrated to ΔΨm in isolated mouse liver mitochondria and oxygen consumption (E, dotted lines) are shown. Mitochondria respired on different substrates, as shown. α-Kg, α-ketoglutarate; βOH, β-hydroxybutyrate; FerrCyan, ferricyanide; glut, glutamate; mal, maleate; Additions were as indicated by the arrows. At the end of each experiment, 1 μM SF 6847 was added to achieve complete depolarization.

Evidently not all diaphorase substrates assisted in preventing mitochondria from being extramitochondrial ATP consumers, which meant that not all of them could be processed by either the diaphorases, and/or reoxidized by complex III. Relevant to this, it is well known that phylloquinone, menaquinone, and Q10 do not react with the isolated diaphorase (10, 67, 68); furthermore, although numerous compounds have been shown to react readily with purified diaphorase (10, 26, 59), there is specificity in the oxidation of the reduced quinone by the respiratory chain (29). Indeed, menadione and DQ have been shown to be processed by the mitochondrial diaphorases and reoxidized by complex III (29, 62).

Lack of a role of diaphorase in the regeneration of NAD+ during anoxia in mitochondria from pigeon liver

The diaphorase activity described in rodent and human tissues has been reported to be absent in the liver and breast muscle of pigeons (Columba livia domestica; refs. 69, 70). We therefore reasoned that in mitochondria obtained from pigeon tissues, the diaphorase inhibitors and substrates would exert no effect. As shown in Fig. 6A–D (black traces), pigeon liver mitochondria respiring on different substrates were repolarized by cATR added after ADP and rotenone, indicating an ATP generation from the forward operation of ANT. The lack of diaphorase involvement in this effect was confirmed by the results that menadione failed to cause a more robust cATR-induced repolarization (Fig. 6A–C, red traces), and none of the diaphorase inhibitors caused cATR-induced depolarization (Fig. 6D). Accordingly, DQ was without an effect on cATR-induced changes in ΔΨm of mitochondria during anoxia (Fig. 6E). These results support the conclusion that the effects of diaphorase substrates and inhibitors observed in mouse liver mitochondria were mediated through genuine diaphorase activity. Furthermore, it is also apparent that in the absence of a diaphorase, pigeon liver mitochondria were still able to maintain the KGDHC-succinyl-CoA ligase axis sustaining substrate-level phosphorylation. Indeed, in Fig. 6F, it is shown that the addition of succinate to pigeon mitochondria reversed the cATR-induced changes in ΔΨm during anoxia from repolarization to depolarization, in accordance with the schemes published recently by our group (2, 6). The validity of this scheme is further supported in pigeon liver mitochondria from the results shown in Fig. 6G, where the addition of atpenin A5, which is expected to lead to a buildup of succinate in the mitochondrial matrix, also led to a cATR-induced depolarization during anoxia (Fig. 6G, red trace).

Figure 6.

A–C) Reconstructed time courses of safranin O signal calibrated to percentage (solid traces; y axes of all panels are as shown in E) reflecting ΔΨm in isolated pigeon liver mitochondria, demonstrating the effect of various mitochondrial and diaphorase substrates on cATR-induced changes in ΔΨm after complex I inhibition by rotenone, with different respiratory substrates used, as indicated. D) Diaphorase inhibitors were present as indicated (dicoumarol, 5 μM; chrysin, 5 μM; diOH-flavone, 20 μM; and phenindione, 10 μM), and mitochondria were supported by glutamate and malate. E–G) Oxygen concentrations in the medium (dotted traces) were measured. Effects of DQ (50 μM; E), various substrates (F), and inhibitors atpenin A5 and KCN (G) are shown. α-Kg, α-ketoglutarate; βOH, β-hydroxybutyrate; AcAc, acetoacetate; glut, glutamate; mal, maleate; rot, rotenone; succ, succinate. At the end of each experiment. 1 μM SF 6847 was added to achieve complete depolarization.

Alternative sources of NAD+ provision in mitochondria during respiratory arrest

From the above data, it is apparent that mitochondrial diaphorases are not the sole providers of NAD+ during anoxia or respiratory inhibition by poisons. An obvious possibility for NAD+ generation would be the malate dehydrogenase (MDH) reaction favoring malate formation from oxaloacetate (71); however, this notion is very difficult to address. We compared WT C57BL/6J mice with another strain expressing an isoform of MDH, which yielded slightly lower activity (MDH2b), but we observed no differences (data not shown). A transgenic or silencing approach for MDH inherently suffers from the pitfall that this enzyme exhibits an extremely high activity compared with that of other enzymes of the citric acid cycle; therefore, one would expect to require very substantial decreases in activity, to observe an effect on NAD+ provision. That there are no MDH-specific inhibitors hindered the ability to study the extent of contribution of MDH in our protocols.

To address the extent of contribution of a proton-translocating transhydrogenase reversibly exchanging NADP+ and NAD+ for NADH and NADPH, respectively (72), which may serve as a source of matrix NAD+, we compared mitochondria obtained from C57Bl/6N vs. C57BL/6J mice, because in the latter strain the gene coding for the transhydrogenase is absent (73, 74). Although the catalytic site of the transhydrogenase for oxidation and reduction of the nicotinamide nucleotides is facing the matrix, extramitochondrial pyridine nucleotides are also required; however, those released from broken mitochondria in our samples may have been sufficient for the exchange to materialize. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S3, cATR-induced repolarization after anoxia in liver mitochondria from C57Bl/6N mice (black trace) was virtually indistinguishable from the mitochondria obtained from C57BL/6J mice (red trace). From this result, we concluded that, in our isolated mitochondria preparations, provision of NAD+ by the transhydrogenase is not a viable possibility. However, it remains as an option in vivo, at least in organisms expressing the transhydrogenase.

DISCUSSION

In earlier work, we have highlighted the critical importance of matrix substrate-level phosphorylation in maintaining ANT operation in the forward mode (2), thereby preventing mitochondria from becoming cytosolic ATP consumers during respiratory arrest (3–5). Succinyl-CoA ligase does not require oxygen for ATP production, and it is even activated during hypoxia (75), providing ATP parallel to that by oxidative phosphorylation (1, 76, 77). More recently, we showed that succinyl-CoA provision by KGDHC prevents isolated or in situ mitochondria with a dysfunctional electron transport chain from being dependent on extramitochondrial ATP (6). Relevant to this, mounting evidence supports the pronounced conversion of α-ketoglutarate to succinate in ischemia and/or hypoxia, implying KGDHC operability (71, 78–93). The question arises as to which metabolic pathways could provide NAD+ for KGDHC during respiratory arrest when the electron transport chain is dysfunctional and complex I cannot oxidize NADH. Of course, a rotenone-mediated block in complex I can be bypassed by succinate or α-glycerophosphate (94), substrates that generate FADH2; however, succinate disfavors substrate-level phosphorylation by the reversible succinyl-CoA ligase due to mass action, while α-glycerophosphate (provided that the mitochondrial α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase activity is sufficiently high; ref. 95) steals endogenous ubiquinones from the diaphorases. We considered mitochondrial diaphorases and a finite pool of oxidizable quinones as potential sources of NAD+ generated within the mitochondrial matrix during respiratory arrest caused by anoxia or poisons of electron transport chain (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Illustration of the pathway linking ATP production by the succinyl-CoA ligase reaction to KGDHC activity, diaphorase activity, reoxidation of diaphorase substrates by complex III, reoxidation of cytochrome c, and rereduction of a cytosolic oxidant.

The results presented herein support the notion that a mitochondrial diaphorase, likely encoded by NQO1 (10, 96), mediates NAD+ regeneration in the mitochondrial matrix during respiratory arrest by anoxia or inhibition of complex I by rotenone. Inexorably, the classic diaphorase inhibitor dicoumarol (10, 26, 30) suffers from potential specificity problems, in that it acts as a mitochondrial uncoupler (56) in addition to inhibiting other enzymes, such as NADH:cytochrome b5 reductase (97). We have compared the cATR-induced effects on ΔΨm in mitochondria during respiratory arrest by rotenone or anoxia from WT vs. Cyb5r2-knockout mice, and the results were indistinguishable (not shown). Furthermore, we titrated dicoumarol and other diaphorase inhibitors and used them at concentrations at which their uncoupling activity was negligible. Finally, none of the diaphorase inhibitors nor any of the diaphorase substrates had an effect on pigeon liver mitochondria, where DT-diaphorase activity was absent (69, 70). On the other hand, pigeon liver mitochondria did show robust cATR-induced repolarizations during respiratory arrest, pointing to alternative mechanisms for providing NAD+ in the matrix. The absence of diaphorase activity in pigeon liver is not surprising; 1–4% of the human population exhibit a polymorphic version of NQO1 that deprives them of NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase activity (98). It may well be that pigeons exhibit the same or a similar polymorphic version of NQO in a much higher percentage of their population.

We also sought the pathways responsible for providing oxidized substrates to the diaphorases. Although various CoQ analogues are maintained in reduced form by the DT-diaphorase (99), their availability is finite (100) and is likely to require a means of reoxidation. Such a pathway has been demonstrated in the mitochondrial matrix; even in the earlier publication by Conover and Ernster (29), it was noted that electrons provided by diaphorase substrates enter the electron transport chain at the level of cytochrome b, which belongs to complex III. Later on, this concept was entertained by Iaguzhinskii's group (62, 63, 101, 102), which examined the stimulatory effect of various diaphorase substrates during cyanide-resistant respiration of isolated mitochondria. Consistent with this, protection in an ischemia model by menadione was abolished by the complex III inhibitor myxothiazol (103). In the same line of investigation, the cytotoxicity caused by complex I inhibition by rotenone, but not that caused by complex III inhibition by antimycin, was prevented by CoQ1 or menadione (104). Furthermore, also consistent with the substrate selectivity of NQOs in HepG2 cells where NQO1 expression is very high (105), both idebenone and CoQ1, but not CoQ10, partially restored cellular ATP levels under conditions of impaired complex I function, in an antimycin-sensitive manner (68). Cytoprotection by rotenone but not antimycin by CoQ1, mediated by NQO1, has also been shown in primary hepatocytes (104) and lymphocytes (61). Menadione has even been shown to support mitochondrial respiration with an inhibited complex I but not complex III before DT-diaphorase was identified (32). This was later confirmed to occur through oxidation of NADH by the intramitochondrial DT-diaphorase (29). Our results clearly show that the reoxidization of substrates being used by the diaphorases for generation of NAD+ during respiratory arrest by rotenone or anoxia is mediated by complex III. In the process, complex III oxidizes cytochrome c (Fig. 7). Therefore, the finiteness of the reducible amount of cytochrome c would contribute to the finiteness of the oxidizable pool of diaphorase substrates. Indeed, addition of FerrCyan led to cATR-induced repolarization in the presence of complex IV inhibition by cyanide, but not in the presence of complex III inhibition by stigmatellin. However, the question arises, as to what could oxidize cytochrome c naturally, when oxygen is not available. An attractive candidate is p66Shc, a protein residing in the intermembrane space of mitochondria (106, 107), which is known to oxidize cytochrome c (107).

In summary, our results point to the importance of mitochondrial diaphorases in providing NAD+ for the KGDHC during anoxia, yielding succinyl CoA, which in turn supports ATP production through substrate-level phosphorylation. In addition, the realization of diaphorases as NAD+ providers renders them a likely target for cancer prevention, as they may be the means of energy harnessing in solid tumors with anoxic/hypoxic centers. Finally, since diaphorases are upregulated by dietary nutrients such as sulforaphane (108) through the Nrf2 pathway (109) and a gamut of dietary elements, mainly quinones of plant origin, are substrates for this enzyme (110), this may be a convenient way to increase the matrix NAD+/NADH ratios that play a role in the activation of the mitochondrial NAD+-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-3 (111), a major metabolic sensor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Országos Tudományos Kutatási Alapprogram (OTKA) grant 81983 and Hungarian Academy of Sciences grant 02001 (to V.A.-V.); a student grant from Astellas Pharma Kft.-Kerpel-Fronius Ödön Tehetséggondozó Program (to G.K.); grant AG014930 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (to A.A.S.); and grants MTA-SE Lendület Neurobiochemistry Research Division 95003, OTKA NNF 78905, OTKA NNF2 85658, and OTKA K 100918 (to C.C). Cyb5r2 transgenic mice were provided by the European Mouse Mutant Archive (EMMA) service project, funded by the EC FP7 Capacities Specific Program.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- ΔΨm

- membrane potential

- 1,2-NQ

- 1,2-naphthoquinone

- 1,4-NQ

- 1,4-naphthoquinone

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- ANT

- adenine nucleotide translocase

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- BQ

- p-benzoquinone

- cATR

- carboxyatractyloside

- CBQ

- 2-chloro-1,4-benzoquinone

- CoQ

- coenzyme Q

- Cyb5r2

- NADH, cytochrome b5 reductase isoform 2

- DCBQ

- 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone

- DCIP

- 2,6-dichloroindophenol

- diOH-flavone

- 7,8-dihydroxyflavone hydrate

- DMBQ

- 2,6-dimethylbenzoquinone

- DQ

- duroquinone

- Erev[lowem]ANT

- reversal potential of adenine nucleotide translocase

- FerrCyan

- ferricyanide

- KGDHC

- α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex

- MBQ

- methyl-p-benzoquinone

- MDH

- malate dehydrogenase

- menadione

- vitamin K3

- menaquinone

- vitamin K2

- mitoQ

- mitoquinone

- NQO

- NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase

- PDHC

- pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

- phylloquinone

- vitamin K1

- SF 6847

- tyrphostin-9,RG-50872,malonaben,3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzylidenemalononitrile,2,6-di-t-butyl-4-(2′,2′-dicyanovinyl)phenol

- TPP

- tetraphenylphosphonium

- WT

- wild type

REFERENCES

- 1. Johnson J. D., Mehus J. G., Tews K., Milavetz B. I., Lambeth D. O. (1998) Genetic evidence for the expression of ATP- and GTP-specific succinyl-CoA synthetases in multicellular eucaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27580–27586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chinopoulos C., Gerencser A. A., Mandi M., Mathe K., Torocsik B., Doczi J., Turiak L., Kiss G., Konrad C., Vajda S., Vereczki V., Oh R. J., Adam-Vizi V. (2010) Forward operation of adenine nucleotide translocase during F0F1-ATPase reversal: critical role of matrix substrate-level phosphorylation. FASEB J. 24, 2405–2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chinopoulos C., Adam-Vizi V. (2010) Mitochondria as ATP consumers in cellular pathology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1802, 221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chinopoulos C. (2011) Mitochondrial consumption of cytosolic ATP: not so fast. FEBS Lett. 585, 1255–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chinopoulos C. (2011) The “B space” of mitochondrial phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. Res. 89, 1897–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kiss G., Konrad C., Doczi J., Starkov A. A., Kawamata H., Manfredi G., Zhang S. F., Gibson G. E., Beal M. F., Adam-Vizi V., Chinopoulos C. (2013) The negative impact of alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex deficiency on matrix substrate-level phosphorylation. FASEB J. 27, 2392–2406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ernster L. (1958) Diaphorase activities in liver cytoplasmic fractions. Fed. Proc. 17, 216 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ernster L., Navazio F. (1958) Soluble diaphorase in animal tissues. Acta Chem. Scand. 12, 595–602 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maerki F., Martius C. (1961) [Vitamin K reductase, from cattle and ratliver] (in German). Biochem. Z. 334, 293–303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ernster L., Danielson L., Ljunggren M. (1962) DT diaphorase, I: purification from the soluble fraction of rat-liver cytoplasm, and properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 58, 171–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wosilait W. D., Nason A. (1954) Pyridine nucleotide-quinone reductase, I: purification and properties of the enzyme from pea seeds. J. Biol. Chem. 206, 255–270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wosilait W. D., Nason A., Terrell A. J. (1954) Pyridine nucleotide-quinone reductase: II, role in electron transport. J. Biol. Chem. 206, 271–282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williams C. H., Jr., Gibbs R. H., Kamin H. (1959) A microsomal TPNH-neotetrazolium diaphorase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 32, 568–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giuditta A., Strecker H. J. (1959) Alternate pathways of pyridine nucleotide oxidation in cerebral tissue. J. Neurochem. 5, 50–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Giuditta A., Strecker H. J. (1961) Purification and some properties of a brain diaphorase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 48, 10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koli A. K., Yearby C., Scott W., Donaldson K. O. (1969) Purification and properties of three separate menadione reductases from hog liver. J. Biol. Chem. 244, 621–629 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iyanagi T., Yamazaki I. (1970) One-electron-transfer reactions in biochemical systems, V: difference in the mechanism of quinone reduction by the NADH dehydrogenase and the NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (DT-diaphorase). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 216, 282–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ernster L. (1987) DT diaphorase: a historical review. Chem. Scripta 27, 1–13 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Long D. J., Jaiswal A. K. (2000) NRH: quinone oxidoreductase2 (NQO2). Chem. Biol. Interact. 129, 99–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vasiliou V., Ross D., Nebert D. W. (2006) Update of the NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase (NQO) gene family. Hum. Genomics 2, 329–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu K., Knox R., Sun X. Z., Joseph P., Jaiswal A. K., Zhang D., Deng P. S., Chen S. (1997) Catalytic properties of NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase-2 (NQO2), a dihydronicotinamide riboside dependent oxidoreductase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 347, 221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhao Q., Yang X. L., Holtzclaw W. D., Talalay P. (1997) Unexpected genetic and structural relationships of a long-forgotten flavoenzyme to NAD(P)H: quinone reductase (DT-diaphorase). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 1669–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dong H., Shertzer H. G., Genter M. B., Gonzalez F. J., Vasiliou V., Jefcoate C., Nebert D. W. (2013) Mitochondrial targeting of mouse NQO1 and CYP1B1 proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 435, 727–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bianchet M. A., Faig M., Amzel L. M. (2004) Structure and mechanism of NAD[P]H: quinone acceptor oxidoreductases (NQO). Methods Enzymol. 382, 144–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eliasson M., Bostrom M., DePierre J. W. (1999) Levels and subcellular distributions of detoxifying enzymes in the ovarian corpus luteum of the pregnant and non-pregnant pig. Biochem. Pharmacol. 58, 1287–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ernster L., Danielson L., Ljunggren M. (1960) Purification and some properties of a highly dicoumarol-sensitive liver diaphorase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2, 88–92 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Danielson L., Ernster L., Ljunggren M. (1960) Selective extraction of DT diaphorase from mitochondria and microsomes. Acta Chem. Scand. 14, 1837–1838 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Edlund C., Elhammer A., Dallner G. (1982) Distribution of newly synthesized DT-diaphorase in rat liver. Biosci. Rep. 2, 861–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Conover T. E., Ernster L. (1962) DT diaphorase, II: relation to respiratory chain of intact mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 58, 189–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Conover T. E., Ernster L. (1960) Mitochondrial oxidation of extra-mitochondrial TPNH1 mediated by purified DT diaphorase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2, 26–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wosilait W. D. (1960) The reduction of vitamin K1 by an enzyme from dog liver. J. Biol. Chem. 235, 1196–1201 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Colpa-Boonstra J. P., Slater E. C. (1958) The possible role of vitamin K in the respiratory chain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 27, 122–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lind C., Hojeberg B. (1981) Biospecific adsorption of hepatic DT-diaphorase on immobilized dicoumarol, II: purification of mitochondrial and microsomal DT-diaphorase from 3-methylcholanthrene-treated rats. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 207, 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ernster L. (1967) DT diaphorase. Methods Enzymol. 10, 309–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Conover T. E., Ernster L. (1963) DT diaphorase. IV. Coupling of extramitochondrial reduced pyridine nucleotide oxidation to mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 67, 268–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Massey V. (1960) The identity of diaphorase and lipoyl dehydrogenase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 37, 314–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klyachko N. L., Shchedrina V. A., Efimov A. V., Kazakov S. V., Gazaryan I. G., Kristal B. S., Brown A. M. (2005) pH-dependent substrate preference of pig heart lipoamide dehydrogenase varies with oligomeric state: response to mitochondrial matrix acidification. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16106–16114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reed L. J., Oliver R. M. (1968) The multienzyme alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes. Brookhaven. Symp. Biol. 21, 397–412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ide S., Hayakawa T., Okabe K., Koike M. (1967) Lipoamide dehydrogenase from human liver. J. Biol. Chem. 242, 54–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bando Y., Aki K. (1992) One- and two-electron oxidation-reduction properties of lipoamide dehydrogenase. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo) Spec No 453–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vaubel R. A., Rustin P., Isaya G. (2011) Mutations in the dimer interface of dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase promote site-specific oxidative damages in yeast and human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40232–40245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tyler D. D., Gonze J. (1967) The preparation of heart mitochondria from laboratory animals. Methods Enzymol. 10, 75–77 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Smith P. K., Krohn R. I., Hermanson G. T., Mallia A. K., Gartner F. H., Provenzano M. D., Fujimoto E. K., Goeke N. M., Olson B. J., Klenk D. C. (1985) Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150, 76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Akerman K. E., Wikstrom M. K. (1976) Safranine as a probe of the mitochondrial membrane potential. FEBS Lett. 68, 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kamo N., Muratsugu M., Hongoh R., Kobatake Y. (1979) Membrane potential of mitochondria measured with an electrode sensitive to tetraphenyl phosphonium and relationship between proton electrochemical potential and phosphorylation potential in steady state. J. Membr. Biol. 49, 105–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Klingenberg M. (2008) The ADP and ATP transport in mitochondria and its carrier. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778, 1978–2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Valle V. G., Pereira-da-Silva L., Vercesi A. E. (1986) Undesirable feature of safranine as a probe for mitochondrial membrane potential. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 135, 189–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chinopoulos C., Adam-Vizi V. (2010) Mitochondrial Ca2+ sequestration and precipitation revisited. FEBS J. 277, 3637–3651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Metelkin E., Demin O., Kovacs Z., Chinopoulos C. (2009) Modeling of ATP-ADP steady-state exchange rate mediated by the adenine nucleotide translocase in isolated mitochondria. FEBS J. 276, 6942–6955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chinopoulos C., Vajda S., Csanady L., Mandi M., Mathe K., Adam-Vizi V. (2009) A novel kinetic assay of mitochondrial ATP-ADP exchange rate mediated by the ANT. Biophys. J. 96, 2490–2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miyadera H., Shiomi K., Ui H., Yamaguchi Y., Masuma R., Tomoda H., Miyoshi H., Osanai A., Kita K., Omura S. (2003) Atpenins, potent and specific inhibitors of mitochondrial complex II (succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 473–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Harris E. J., Achenjang F. M. (1977) Energy-dependent uptake of arsenite by rat liver mitochondria. Biochem. J. 168, 129–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Clark J. B., Land J. M. (1979) Inhibitors of mitochondrial enzymes. Pharmacol. Ther. 7, 351–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pagliarini D. J., Calvo S. E., Chang B., Sheth S. A., Vafai S. B., Ong S. E., Walford G. A., Sugiana C., Boneh A., Chen W. K., Hill D. E., Vidal M., Evans J. G., Thorburn D. R., Carr S. A., Mootha V. K. (2008) A mitochondrial protein compendium elucidates complex I disease biology. Cell 134, 112–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Winski S. L., Koutalos Y., Bentley D. L., Ross D. (2002) Subcellular localization of NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 62, 1420–1424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Martius C., Nitz-litzow D. (1953) The mechanism of action of dicumarol and related compounds. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 12, 134–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Faig M., Bianchet M. A., Winski S., Hargreaves R., Moody C. J., Hudnott A. R., Ross D., Amzel L. M. (2001) Structure-based development of anticancer drugs: complexes of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 with chemotherapeutic quinones. Structure 9, 659–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tedeschi G., Chen S., Massey V. (1995) DT-diaphorase. Redox potential, steady-state, and rapid reaction studies. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1198–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lind C., Cadenas E., Hochstein P., Ernster L. (1990) DT-diaphorase: purification, properties, and function. Methods Enzymol. 186, 287–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Giuditta A., Strecker H. J. (1963) Brain NADH-tretraazolium reductase activity, lipomide dehydrogenase and activating lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 67, 316–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dedukhova V. I., Kirillova G. P., Mokhova E. N., Rozovskaia I. A., Skulachev V. P. (1986) [Effect of menadione and vicasol on mitochondrial energy during inhibition of initiation sites of the respiration chain] (in Russian). Biokhimiia 51, 567–573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kolesova G. M., Karnaukhova L. V., Iaguzhinskii L. S. (1991) [Interaction of menadione and duroquinone with Q-cycle during DT-diaphorase function] (in Russian). Biokhimiia 56, 1779–1786 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kolesova G. M., Karnaukhova L. V., Segal' N. K., Iaguzhinskii L. S. (1993) [The effect of inhibitors of the Q-cycle on cyano-resistant oxidation of malate by rat liver mitochondria in the presence of menadione] (in Russian). Biokhimiia 58, 1630–1640 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ernster L., Lee I. Y., Norling B., Persson B. (1969) Studies with ubiquinone-depleted submitochondrial particles: essentiality of ubiquinone for the interaction of succinate dehydrogenase, NADH dehydrogenase, and cytochrome b. Eur. J. Biochem. 9, 299–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Flatmark T. (1967) Multiple molecular forms of bovine heart cytochrome c. V. A comparative study of their physicochemical properties and their reactions in biological systems. J. Biol. Chem. 242, 2454–2459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gopal D., Wilson G. S., Earl R. A., Cusanovich M. A. (1988) Cytochrome c: ion binding and redox properties—studies on ferri and ferro forms of horse, bovine, and tuna cytochrome c. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 11652–11656 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Preusch P. C., Smalley D. M. (1990) Vitamin K1 2,3-epoxide and quinone reduction: mechanism and inhibition. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 8, 401–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Haefeli R. H., Erb M., Gemperli A. C., Robay D., Courdier F., I, Anklin C., Dallmann R., Gueven N. (2011) NQO1-dependent redox cycling of idebenone: effects on cellular redox potential and energy levels. PLoS.ONE. 6, e17963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Danielson L., Ernster L. (1962) Lack of relationship between mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and the dicoumarol-sensitive flavoenzyme ‘DT diaphorase’ or ‘vitamin K reductase’. Nature 194, 155–157 [Google Scholar]

- 70. Martius C., Strufe R. (1954) [Phylloquinone reductase; preliminary report] (in German). Biochem. Z. 326, 24–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chinopoulos C. (2013) Which way does the citric acid cycle turn during hypoxia?—the critical role of alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. J. Neurosci. Res. 91, 1030–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jackson J. B. (1991) The proton-translocating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide transhydrogenase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 23, 715–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Toye A. A., Lippiat J. D., Proks P., Shimomura K., Bentley L., Hugill A., Mijat V., Goldsworthy M., Moir L., Haynes A., Quarterman J., Freeman H. C., Ashcroft F. M., Cox R. D. (2005) A genetic and physiological study of impaired glucose homeostasis control in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetologia 48, 675–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Freeman H. C., Hugill A., Dear N. T., Ashcroft F. M., Cox R. D. (2006) Deletion of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase: a new quantitive trait locus accounting for glucose intolerance in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetes 55, 2153–2156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Phillips D., Aponte A. M., French S. A., Chess D. J., Balaban R. S. (2009) Succinyl-CoA synthetase is a phosphate target for the activation of mitochondrial metabolism. Biochemistry 48, 7140–7149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nicholls D. G., Bernson V. S. (1977) Inter-relationships between proton electrochemical gradient, adenine-nucleotide phosphorylation potential and respiration, during substrate-level and oxidative phosphorylation by mitochondria from brown adipose tissue of cold-adapted guinea-pigs. Eur. J. Biochem. 75, 601–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lambeth D. O., Tews K. N., Adkins S., Frohlich D., Milavetz B. I. (2004) Expression of two succinyl-CoA synthetases with different nucleotide specificities in mammalian tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36621–36624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Pisarenko O., Studneva I., Khlopkov V., Solomatina E., Ruuge E. (1988) An assessment of anaerobic metabolism during ischemia and reperfusion in isolated guinea pig heart. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 934, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Peuhkurinen K. J., Takala T. E., Nuutinen E. M., Hassinen I. E. (1983) Tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolites during ischemia in isolated perfused rat heart. Am. J. Physiol. 244, H281–H288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sanborn T., Gavin W., Berkowitz S., Perille T., Lesch M. (1979) Augmented conversion of aspartate and glutamate to succinate during anoxia in rabbit heart. Am. J. Physiol. 237, H535–H541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pisarenko O. I., Solomatina E. S., Ivanov V. E., Studneva I. M., Kapelko V. I., Smirnov V. N. (1985) On the mechanism of enhanced ATP formation in hypoxic myocardium caused by glutamic acid. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 80, 126–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Pisarenko O., Studneva I., Khlopkov V. (1987) Metabolism of the tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates and related amino acids in ischemic guinea pig heart. Biomed. Biochim. Acta 46, S568–S571 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hunter F. E., Jr. (1949) Anaerobic phosphorylation due to a coupled oxidation-reduction between alpha-ketoglutaric acid and oxalacetic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 177, 361–372 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Chance B., Hollunger G. (1960) Energy-linked reduction of mitochondrial pyridine nucleotide. Nature 185, 666–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Randall H. M., Jr., Cohen J. J. (1966) Anaerobic CO2 production by dog kidney in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. 211, 493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sanadi D. R., Fluharty A. L. (1963) On the mechanism of oxidative phosphorylation, VII: the energy-requiring reduction of pyridine nucleotide by succinate and the energy-yielding oxidation of reduced pyridine nucleotide by fumarate. Biochemistry 2, 523–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Penney D. G., Cascarano J. (1970) Anaerobic rat heart: effects of glucose and tricarboxylic acid-cycle metabolites on metabolism and physiological performance. Biochem. J. 118, 221–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Wilson M. A., Cascarano J. (1970) The energy-yielding oxidation of NADH by fumarate in submitochondrial particles of rat tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 216, 54–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Taegtmeyer H., Peterson M. B., Ragavan V. V., Ferguson A. G., Lesch M. (1977) De novo alanine synthesis in isolated oxygen-deprived rabbit myocardium. J. Biol. Chem. 252, 5010–5018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Taegtmeyer H. (1978) Metabolic responses to cardiac hypoxia. Increased production of succinate by rabbit papillary muscles. Circ. Res. 43, 808–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Chick W. L., Weiner R., Cascareno J., Zweifach B. W. (1968) Influence of Krebs-cycle intermediates on survival in hemorrhagic shock. Am. J. Physiol. 215, 1107–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Weinberg J. M., Venkatachalam M. A., Roeser N. F., Saikumar P., Dong Z., Senter R. A., Nissim I. (2000) Anaerobic and aerobic pathways for salvage of proximal tubules from hypoxia-induced mitochondrial injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 279, F927–F943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Weinberg J. M., Venkatachalam M. A., Roeser N. F., Nissim I. (2000) Mitochondrial dysfunction during hypoxia/reoxygenation and its correction by anaerobic metabolism of citric acid cycle intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 2826–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Estabrook R. W., Sacktor B. (1958) alpha-Glycerophosphate oxidase of flight muscle mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 233, 1014–1019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Tretter L., Takacs K., Kover K., Adam-Vizi V. (2007) Stimulation of H(2)O(2) generation by calcium in brain mitochondria respiring on alpha-glycerophosphate. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 3471–3479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Preusch P. C., Siegel D., Gibson N. W., Ross D. (1991) A note on the inhibition of DT-diaphorase by dicoumarol. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 11, 77–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Hodnick W. F., Sartorelli A. C. (1993) Reductive activation of mitomycin C by NADH: cytochrome b5 reductase. Cancer Res. 53, 4907–4912 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Traver R. D., Siegel D., Beall H. D., Phillips R. M., Gibson N. W., Franklin W. A., Ross D. (1997) Characterization of a polymorphism in NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase (DT-diaphorase). Br. J. Cancer 75, 69–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Beyer R. E., Segura-Aguilar J., Di B. S., Cavazzoni M., Fato R., Fiorentini D., Galli M. C., Setti M., Landi L., Lenaz G. (1996) The role of DT-diaphorase in the maintenance of the reduced antioxidant form of coenzyme Q in membrane systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 2528–2532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Lenaz G., Fato R., Degli E. M., Rugolo M., Parenti C. G. (1985) The essentiality of coenzyme Q for bioenergetics and clinical medicine. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res. 11, 547–556 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kolesova G. M., Kapitanova N. G., Iaguzhinskii L. S. (1987) [Stimulation by quinones of cyanide-resistant respiration in rat liver and heart mitochondria] (in Russian). Biokhimiia 52, 715–719 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Kolesova G. M., Vishnivetskii S. A., Iaguzhinskii L. S. (1989) [A study of the mechanism of cyanide resistant oxidation of succinate from rat liver mitochondria in the presence of menadione] (in Russian). Biokhimiia 54, 103–111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yue Y., Krenz M., Cohen M. V., Downey J. M., Critz S. D. (2001) Menadione mimics the infarct-limiting effect of preconditioning in isolated rat hearts. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 281, H590–H595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Chan T. S., Teng S., Wilson J. X., Galati G., Khan S., O'Brien P. J. (2002) Coenzyme Q cytoprotective mechanisms for mitochondrial complex I cytopathies involves NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1(NQO1). Free Radic. Res. 36, 421–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Cresteil T., Jaiswal A. K. (1991) High levels of expression of the NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) gene in tumor cells compared to normal cells of the same origin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 42, 1021–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Ventura A., Maccarana M., Raker V. A., Pelicci P. G. (2004) A cryptic targeting signal induces isoform-specific localization of p46Shc to mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2299–2306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]