Abstract

Objective

This study aims to assess the role of need factors with respect to the utilisation of institutional delivery services in Nepal.

Design

An analytic study was conducted using a subset of 4079 ever married women from the 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, which utilised two-stage cluster sampling. Logistic regression with complex sample analysis was performed to evaluate the effects of antenatal care visits and birth preparedness activities on facility delivery.

Outcome measures

Facility delivery.

Results

Overall facility delivery rate was low at 36.9% (95% CI 33.5% to 40.2%, SE 1.69). Only half (50.1%) of the women made four or more antenatal care visits while 62.9% (95% CI 59.9% to 65.8%, SE 1.51) did not indicate any of the four birth preparation activities. After adjusting for external, predisposing and enabling factors, women who made more than four antenatal care visits were five times more likely to deliver at a health facility when compared to those who paid no visit (adjusted OR 4.94, 95% CI 3.14 to 7.76). Similarly, the likelihood for facility delivery increased by 3.4-fold among women who prepared for at least two of the four activities compared to their counterparts who made no preparation (adjusted OR 3.41, 95% CI 2.01 to 5.58).

Conclusions

The perceived need, as expressed by the frequency of antenatal care visits and birth preparedness activities, plays an important role in institutional delivery service utilisation for Nepali women. These findings have implications for behavioural interventions to change their intention to deliver at a health facility.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used the nationally representative large sample of married women from the 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey with a high response rate.

Information was not available on some known determinants of facility delivery utilisation, particularly quality of providers, and distance and transportation to facility.

Perceived need of facility delivery was assessed by antenatal visits and birth preparedness activities, which were positively associated with facility delivery utilisation.

Introduction

Globally, nearly all (99%) maternal deaths occur in low-income countries, mainly caused by non-utilisation of available delivery services or delays in accessing such services.1 2 Indeed, about half of all births in South Asia still occur at home.3 A number of interventions have been implemented to increase the rate of facility delivery and access to emergency obstetric care, including the establishment of birth centres and maternity waiting homes, reduction of user fees, provision of incentives and birth preparedness packages.4 5 The ‘safer mother programme’ in Nepal provides free delivery services with incentives to women who deliver in a designated health facility.6

In Nepal, despite a substantial reduction in maternal mortality from 539 deaths/100 000 live-births in 1996 to 281 deaths/100 000 in 2006, there has been no proportionate increase in utilisation of institutional delivery service.7 The 2011 national survey reported that 65% of women still delivered at home and only 36% of births occurred in the presence of a skilled birth attendant,8 whereas the national target is to achieve 60% of births via skilled birth attendants by 2015, in order to meet the Millennium Development Goal 5 target of 134/100 000 live-births.9 Therefore, utilisation of institutional delivery service is a major concern in Nepal.

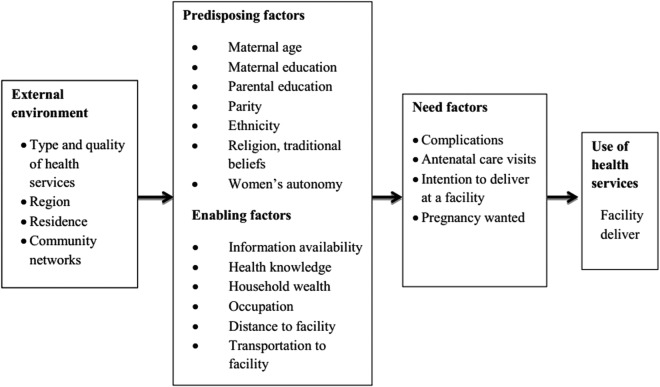

According to the behavioural model proposed by Andersen,10 need factors are fundamental to healthcare seeking behaviour, that is, one should perceive a condition as susceptible and severe enough before seeking care to gain benefits. For institutional delivery service utilisation, this means that the pregnant woman and her family must recognise pregnancy and childbirth as abnormal events, where life-threatening situations may arise without any prediction.11 In many low-income countries including Nepal, pregnancy and childbirth are often perceived as normal life events without justification to seek professional help.12 13 In fact, need factors can be driven by pregnancy-related factors such as awareness, health knowledge of pregnancy and risk, importance given to pregnancy, community customs, previous facility use, parity and pregnancy complications.14 Those women who perceive the need for professional help and recognise the risk of pregnancy and delivery, are expected to make antenatal visits and prepare and arrange for childbirth.15 Besides the immediate need, utilisation of institutional delivery service can be affected by predisposing and enabling factors as well as external environment factors. Figure 1 depicts the conceptual framework, which is adapted from Andersen's10 behavioural model for the utilisation of health services.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of factors associated with the utilisation of institutional delivery services.

Despite the important role of need factors, their effect on utilisation of institutional delivery service has seldom been investigated in the context of safe motherhood programmes. The aim of the present study was to assess the contribution of need factors with respect to the utilisation of institutional delivery service in Nepal, using data from the national Nepal Demographic Health Survey (NDHS). Need factors were assessed by antenatal care visits and birth preparedness activities.

Methods

Study setting

Nepal, with a population of 27.5 million, is divided into five developmental regions, each extending from north to south. The country has also three ecological zones across east to west: Terai, hill and mountain. These 15 subecological regions are further divided into smaller districts. Typically, each district has Village Development Committees (VDC) in rural areas and municipalities in urban areas. Each VDC or municipality in turn consists of small administrative units known as wards.

Data and sampling

The data for this study were obtained from the 2011 NDHS conducted by the Ministry of Health and Population.16 Details of the sampling methodology had been described elsewhere.8 Briefly, the survey utilised a two-stage cluster sampling design with wards (enumeration areas) being the primary sampling units. The wards were stratified by subecological domains and by rural–urban residency. In total, 11 085 households were selected as listing units from these 289 wards. Among them, 12 961 women aged 15–49 years were identified as eligible but individual interviews were only completed for 12 699 women, giving a response rate of 98%. This study focused on the subset of 4079 ever married women who had given birth within the past 5 years preceding the survey and who provided information on antenatal visits and preparation activities.

Statistical analysis

The outcome variable was ‘place of delivery’: home versus facility (private or public). This binary variable was chosen instead of ‘assisted deliveries’ to emphasise the use of institutional delivery services and to avoid the potential problem of inaccurate reporting of birth attendant skills. Perceived need factors investigated were (1) frequency of antenatal care visits and (2) birth preparedness. The latter referred to four preparation activities, namely, planning for a birth attendant, saving money, arrangement for transportation and identification of potential blood donator.17 Although the 2011 NDHS collected information on planning activities related to preparation of clothes, delivery kit and food, these activities did not necessarily imply the need for facility delivery; consequently, they were not considered as need factors of institutional delivery service use.

Table 1 gives the classification of variables used in this study. These variables were chosen in view of the conceptual framework of factors associated with the utilisation of institutional delivery services (figure 1). NDHS applied principal component analysis of a range of household assets to generate wealth quintiles. Ethnicity was categorised by three groups: upper caste (Hill Brahmin, Hill Cheetri, Terai Brahmin, Terai Cheetri), lower caste (Hill Dalit, Terai Dalit) and other (all other recorded ethnicities). Education was classified as none, primary (1–5 grade), secondary (6–10 grade) and higher (after 10th grade).

Table 1.

Classification of variables used in the analysis (n=4079)

| Variables | Categories | Weighted percentage | Unweighted count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of delivery | Home | 63.1 | 2397 |

| Facility | 36.9 | 1682 | |

| Antenatal care visits | 0 | 15.2 | 611 |

| 1 | 6.1 | 234 | |

| 2 | 12.2 | 426 | |

| 3 | 16.4 | 657 | |

| 4 | 19.7 | 901 | |

| ≥5 | 30.4 | 1250 | |

| Birth preparedness* | 0 | 62.9 | 2476 |

| 1 | 33.3 | 1440 | |

| ≥2 | 3.8 | 163 | |

| Women's age (years) | 15–19 | 7.1 | 306 |

| 20–24 | 33.4 | 1273 | |

| 25–29 | 32.2 | 1335 | |

| 30–49 | 27.3 | 1165 | |

| Women's education | None | 47.3 | 1765 |

| Primary | 20.0 | 817 | |

| Secondary | 27.2 | 1225 | |

| Higher | 5.5 | 272 | |

| Partner's education | None | 23.2 | 745 |

| Primary | 24.5 | 989 | |

| Secondary | 42.1 | 1815 | |

| Higher | 10.2 | 514 | |

| Parity | 1 | 24.2 | 1248 |

| 2 | 30.6 | 1157 | |

| 3 | 19.3 | 690 | |

| 4 | 10.8 | 440 | |

| ≥5 | 15.1 | 544 | |

| Wealth quintiles | 1 | 25.8 | 1160 |

| 2 | 21.9 | 832 | |

| 3 | 21.0 | 739 | |

| 4 | 17.4 | 677 | |

| 5 | 13.9 | 671 | |

| Ethnicity | Other | 52.1 | 1813 |

| Upper caste | 30.1 | 1552 | |

| Lower caste | 17.8 | 703 | |

| Region | Mountain | 7.9 | 742 |

| Hill | 39.5 | 1656 | |

| Terai | 52.6 | 1681 | |

| Residential location | Rural | 90.7 | 3182 |

| Urban | 9.3 | 897 |

*Birth preparedness consists of four preparation activities (planning for a birth attendant, saving money, arrangement for transportation and identification of potential blood donator).

In the 2011 NDHS, enumeration areas were not allocated proportional to their population size, thus requiring adjustment by sampling weights prior to analysis. Such sampling weights were provided by the survey to account for cluster level variables and strata (domain) level variables. Based on these sampling weights, a complex sampling plan file was then prepared to perform logistic regression modelling, with need factors and other confounding factors listed in table 1. All statistical analyses were conducted in the SPSS package V.21.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 4079 eligible women. About half of the participants had no education (47.3%) and came from the Terai region (52.6%). Almost two-third of them were between 20 and 29 years of age. Although half (50.1%) of the eligible women made four or more antenatal care visits, 15.2% never visited a health facility before giving birth. The majority of mothers (62.9%) did not indicate any of the four birth preparation activities, while no woman prepared for all four activities.

The overall facility delivery rate was found to be 36.9% (95% CI 33.5% to 40.2%, SE 1.69). Table 2 presents the results of logistic regression analysis. The confounding factors used were woman's age, woman's education, partner's education, parity, wealth quintiles, ethnicity, region and residential location from the NDHS 2011 data set. Both need factors were positively associated with the facility delivery status. Even after simultaneously adjusting the effects of predisposing, enabling and external environment factors, the two need factors remained statistically significant (p<0.001). In particular, women who made five or more antenatal care visits were almost five times more likely to deliver at a health facility when compared to those who paid no visit prior to delivery (adjusted OR 4.94, 95% CI 3.14 to 7.76). Similarly, the likelihood for facility delivery increased by 3.4-fold among women who prepared for at least two of the four activities, relative to their counterparts who chose to make no preparation (adjusted OR 3.41, 95% CI 2.01 to 5.58). The multivariable logistic regression analysis also confirmed that wealth quintiles, residential location and higher parity were significantly associated with place of delivery.

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted ORs of facility delivery from logistic regression with complex sampling analysis (n=4079)

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Need factors | |||

| Antenatal care visits | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | 1.79 (1.03 to 3.10) | 1.30 (0.72 to 2.34) | |

| 2 | 2.58 (1.62 to 4.10) | 1.75 (1.07 to 2.93) | |

| 3 | 4.18 (2.69 to 6.50) | 2.21 (1.39 to 3.43) | |

| 4 | 8.71 (5.40 to 14.05) | 4.13 (2.51 to 6.44) | |

| ≥5 | 17.89 (11.23 to 28.51) | 4.94 (3.14 to 7.76) | |

| Birth preparedness† | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | 2.68 (2.18 to 3.30) | 1.52 (1.19 to 1.88) | |

| ≥2 | 9.31 (5.71 to 15.17) | 3.41 (2.01 to 5.58) | |

| Confounding factors | |||

| Women's age (years) | 0.083 | ||

| 15–19 | 1 | 1 | |

| 20–24 | 0.65 (0.49 to 0.86) | 0.65 (0.44 to 0.97) | |

| 25–29 | 0.56 (0.42 to 0.75) | 0.69 (0.48 to 1.00) | |

| 30–49 | 0.36 (0.26 to 0.49) | 0.80 (0.49 to 1.32) | |

| Women's education | 0.216 | ||

| None | 1 | 1 | |

| Primary | 1.91 (1.46 to 2.51) | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.42) | |

| Secondary | 5.35 (4.25 to 6.72) | 1.29 (0.97 to 1.71) | |

| Higher | 20.28 (12.22 to 33.65) | 1.67 (0.89 to 3.12) | |

| Partner's education | 0.467 | ||

| None | 1 | 1 | |

| Primary | 1.61 (1.17 to 2.21) | 0.94 (0.67 to 1.30) | |

| Secondary | 3.62 (2.63 to 4.98) | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.33) | |

| Higher | 11.19 (7.34 to 17.04) | 1.28 (0.78 to 2.09) | |

| Parity | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0.44 (0.35 to 0.54) | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.58) | |

| 3 | 0.21 (0.16 to 0.28) | 0.39 (0.28 to 0.54) | |

| 4 | 0.18 (0.13 to 0.25) | 0.42 (0.28 to 0.63) | |

| ≥5 | 0.08 (0.06 to 0.12) | 0.30 (0.19 to 0.49) | |

| Wealth quintiles | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | 2.14 (1.68 to 2.73) | 1.58 (1.19 to 2.11) | |

| 3 | 3.73 (2.80 to 4.96) | 2.03 (1.44 to 2.86) | |

| 4 | 7.25 (5.33 to 9.88) | 2.73 (1.90 to 3.94) | |

| 5 | 24.17 (17.51 to 33.35) | 6.17 (3.94 to 9.67) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.607 | ||

| Other | 1 | 1 | |

| Upper caste | 1.56 (1.22 to 2.01) | 1.08 (0.81 to 1.42) | |

| Lower caste | 0.72 (0.57 to 0.92) | 1.16 (0.85 to 1.59) | |

| Region | 0.244 | ||

| Mountain | 1 | 1 | |

| Hill | 1.94 (1.28 to 2.95) | 1.28 (0.86 to 1.92) | |

| Terai | 2.78 (1.86 to 4.14) | 1.43 (0.94 to 2.19) | |

| Residential location | <0.001 | ||

| Rural | 1 | 1 | |

| Urban | 5.19 (3.99 to 6.75) | 2.42 (1.83 to 3.19) | |

*From multivariable logistic regression model.

†Birth preparedness consists of four preparation activities (planning for a birth attendant, saving money, arrangement for transportation and identification of potential blood donator).

Discussion

The national survey data revealed the majority of Nepali mothers did not prepare any of the four activities and only half of the women made the recommended four or more antenatal care visits, despite birth preparedness being incorporated into the national safe motherhood programme since 2009.12 Female community health volunteers and facility-based health workers use pictorial charts to educate women on obstetric danger signs. While preparedness level can be high in some districts,18 overall birth preparedness is still low. The variations between districts may be attributed to differences in human development indexes including adult literacy, women empowerment and physical accessibility to health facilities.

Overall, the preparation and antenatal visit record suggested that women might have no intention or might not perceive the need of giving birth at a heath facility. Such perception of need can also be influenced by distance and quality of maternity services.14 19 Indeed, the facility delivery rate was found to be only 36.9%. In the traditional Nepalese society, childbirth continues to take place at home, while many women still hold the view that facility delivery is unnecessary. On the other hand, those women who were prepared and made antenatal visits tended to give birth at facilities. Our results confirmed the strong contribution by these need factors to actual facility utilisation irrespective of predisposing, enabling and external environment factors. Apart from the need factors, parity, wealth status and residential location also play a significant role in the choice of delivery place.

Although the frequency of antenatal care visits was associated with subsequent facility delivery, the relationship appeared to be dose-dependent,14 18 as in the case of the present study whereby making a single visit induced no significant impact; whereas previous studies undertaken in Tanzania observed high use of antennal care but low use of facility delivery.20 21 Making the recommended four or more antenatal care visits might reflect the woman's concern of her pregnancy, pregnancy complications and the need for professional help.14 22 Consequently, informing women about danger signs and providing quality antenatal care with provision of iron tablets and blood check might encourage women to attend antenatal visits.

The link between birth preparedness activities and facility delivery was supported by recent literature. A prospective cohort study of 701 pregnant women in the Kaski district of Nepal found preparation activities could increase the facility delivery rate.18 Similarly, a randomised trial in Tanzania demonstrated that skilled delivery care uptake was 16.8% higher among women who had been counselled on promotion of birth plan than others without such counselling.23 Raising awareness and help for birth plan also led to increased facility utilisation in other intervention studies conducted in Burkina Faso, Bangladesh and Eritrea.24–26 However, two prepost evaluation studies of birth preparedness in southern districts of Nepal reported that increased preparedness level was not significantly translated into increased facility delivery.27 28

The findings have important implications for safe motherhood programme in Nepal and other low-income countries. As the intention to deliver at a heath facility can be largely influenced by need factors, women should be extensively counselled on and convinced of the benefits and safety of facility delivery. Any behavioural intervention such as birth preparedness package and complication readiness is unlikely to be successful unless it attains a high level capacity to change the women's attitude and intention. Counselling can be performed by health professionals, preferably female health workers at a health facility or by female community health volunteers at household visits. Further, local teachers and social workers can be involved in awareness raising campaigns. Community networks and mother clubs can also provide support in terms of money and transport management.

The strength of the present study was the use of a nationally representative large sample of married women with a high response rate. However, information was lacking on some known determinants of facility delivery utilisation, particularly quality of providers and distance and transportation to facility. These variables were unavailable from the NDHS 2011 database and posed as the major limitation. Nevertheless, the external factors ‘residential location’ and ‘region’ have provided some proxy information to partially compensate the effect of distance and service availability. Institutional delivery services in Terai and urban areas are more physically accessible than in hilly or mountainous parts of the country. The regression model has accounted for region and location as well as other known predisposing and enabling factors.

Conclusion

Utilisation of institutional delivery services remained low in Nepal. The majority of mothers were not prepared for childbirth and only half the women made the recommended four or more antennal care visits, indicating their perceived lack of need for facility delivery. The national data confirmed the strong associations between such need factors and institutional delivery service utilisation. This has implications for behavioural interventions such as birth preparedness and complication readiness, which aim to change their intention to deliver at a health facility. Birth preparedness packages in Nepal should be continued and future interventions should target the need factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the ICF International, Calverton, Maryland, USA, for providing the data for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: RK conceived the study design, performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. AHL supervised the statistical analysis and revised the paper. VK prepared the data set and assisted with interpretation of the data. All the authors have read and approved the final version for publication.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The 2011 Nepal Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) survey was approved by the Nepal Health Research Council.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data of 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey can be obtained from MEASURE DHS ICF International, Calverton, Maryland, USA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Trends in maternal mortality 1990 to 2010. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and World Bank Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet 2006;368:1189–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations The millenium development goals report 2013. New York: United Nations, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metcalfe R, Adegoke AA. Strategies to increase facility-based skilled birth attendance in South Asia: a literature review. Int Health 2013;5:96–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Brouwere V, Richard F, Witter S. Access to maternal and perinatal health services: lessons from successful and less successful examples of improving access to safe delivery and care of the newborn. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:901–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karkee R, Lee A, Binns C. Determinants of facility delivery after implementation of safer mother programme in Nepal: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karkee R. How did Nepal reduce the maternal mortality? A result from analysing the determinants of maternal mortality. J Nepal Med Assoc 2012;52:88–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MoHP [Nepal], New ERA, ICF International Inc Nepal demographic and health survey 2011. Kathmandu, Nepal; Calverton, MD: Ministry of Health and Population [Nepal], New ERA, and ICF International Inc., 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Planning Commission/UN Country Team of Nepal Nepal millennium development goals progress report 2010. Kathmandu: National Planning Commission, Government of Nepal/UN Country Team of Nepal, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1091–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pradhan A, Suvedi BK, Barnett S, et al. Nepal maternal mortality and morbidity study 2008/2009. Kathmandu: Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agus Y, Shigeko H, Porter SE. Rural Indonesia women's traditional beliefs about antenatal care. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabrysch S, Campbell OMR. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.JHPIEGO Behaviour change intervention for safe motherhood: common problems, unique solutions. Baltimore: JHPIEGO, Maternal and Neonatal Health Programme, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 16.MEASURE DHS/ICF International. http://www.measuredhs.com/data/dataset/Nepal_Standard-DHS_2011.cfm?flag=0 (accessed 15 Jan 2014)

- 17.JHPIEGO Monitoring birth preparedness and complication readiness, tools and indicators for maternal and newborn health. Baltimore: JHPIEGO, Maternal and Neonatal Health Programme, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karkee R, Lee A, Binns C. Birth preparedness and skilled attendance at birth in Nepal: implications for achieving Millennium Development Goal 5. Midwifery 2013;29:1206–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acharya LB, Cleland J. Maternal and child health services in rural Nepal: does access or quality matter more? Health Policy Plan 2000;15:223–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mpembeni RNM, Killewo JZ, Leshabari MT, et al. Use pattern of maternal health services and determinants of skilled care during delivery in Southern Tanzania: implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2007;7:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magoma M, Requejo J, Campbell O, et al. High ANC coverage and low skilled attendance in a rural Tanzanian district: a case for implementing a birth plan intervention. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Titaley C, Dibley M, Roberts C. Factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care services in Indonesia: results of Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2002/2003 and 2007. BMC Public Health 2010;10:485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magoma M, Requejo J, Campbell O, et al. The effectiveness of birth plans in increasing use of skilled care at delivery and postnatal care in rural Tanzania: a cluster randomised trial. Trop Med Int Health 2013;18:435–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brazier E, Andrzejewski C, Perkins ME, et al. Improving poor women's access to maternity care: findings from a primary care intervention in Burkina Faso. Soc Sci Med 2009; 69:682–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hossain J, Ross SR. The effect of addressing demand for as well as supply of emergency obstetric care in Dinajpur, Bangladesh. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2006;92:320–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turan JM, Tesfagiorghis M, Polan ML. Evaluation of a community intervention for promotion of safe motherhood in Eritrea. J Midwifery Womens Health 2011;56:8–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McPherson R, Khadka N, Moore J, et al. Are birth-preparedness programmes effective? Results from a field trial in Siraha district, Nepal. J Health Popul Nutr 2006;24:479–88 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodgins S, McPherson R, Suvedi BK, et al. Testing a scalable community-based approach to improve maternal and neonatal health in rural Nepal. J Perinatol 2010;30:388–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.