Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact of a quality improvement project that used a multifaceted educational intervention on how to improve clinician's knowledge, confidence and awareness of acute kidney injury (AKI).

Setting

2 large acute teaching hospitals in England, serving a combined population of over 1.5 million people.

Participants

All secondary care clinicians working in the clinical areas were targeted, with a specific focus on clinicians working in acute admission areas.

Interventions

A multifaceted educational intervention consisting of traditional didactic lectures, case-based teaching in small groups and an interactive web-based learning resource.

Outcome measures

We assessed clinicians’ knowledge of AKI and their self-reported clinical behaviour using an interactive questionnaire before and after the educational intervention. Secondary outcome measures included clinical audit of patient notes before and after the intervention.

Results

26% of clinicians reported that they were aware of local AKI guidelines in the preintervention questionnaire compared to 64% in the follow-up questionnaire (χ²=60.2, p<0.001). There was an improvement in the number of clinicians reporting satisfactory practice when diagnosing AKI, 50% vs 68% (χ²=12.1, p<0.001) and investigating patients with AKI, 48% vs 64% (χ²=9.5, p=0.002). Clinical audit makers showed a trend towards better clinical practice.

Conclusions

This quality improvement project utilising a multifaceted educational intervention improved awareness of AKI as demonstrated by changes in the clinician's self-reported management of patients with AKI. Elements of the project have been sustained beyond the project period, and demonstrate the power of quality improvement projects to help initiate changes in practice. Our findings are limited by confounding factors and highlight the need to carry out formal randomised studies to determine the impact of educational initiatives in the clinical setting.

Keywords: Education & Training (see Medical Education & Training), General Medicine (see Internal Medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

It is known that acute kidney injury (AKI) is associated with high mortality and morbidity. The 2009 National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcomes and Death (NCEPOD) report ‘Adding insult to injury’ identified deficiencies in the quality of care given to patients with AKI and in the education and training of healthcare professionals. Until now, there is no clear evidence on how best to improve outcomes for patients with AKI.

- Our project has shown that a multifaceted educational intervention delivered as a quality improvement (QI) project targeted at non-nephrologists can:

- Increase awareness of AKI guidelines.

- Improve self-reported confidence in diagnosing and investigating patients with AKI.

- Show an improvement towards better clinical audit markers.

- Demonstrate the effectiveness of a QI project to initiate long-term changes in practice.

However, this project was not a randomised study, so there are limiting factors to consider, including changes in the confidence of clinicians as a result of increased clinical experience and differences in the number of clinicians sampled at the start and completion of the project. The potential impact of these limitations on the results is discussed in this paper, but we suggest that future work is needed to assess the impact of educational interventions on clinical outcomes.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is associated with significant mortality and morbidity; in the UK, mortality has been reported to be as high as 40%.1 The cost of treating patients with AKI is substantial; data from the Intensive Care National Audit Research Centre suggested that AKI accounted for almost 10% of all intensive care unit bed days.2 The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcomes and Death (NCEPOD) report into the management of AKI in England entitled ‘Adding Insult to Injury’3 concluded that the majority of patients with AKI did not receive optimum care, and death may have been preventable in a significant number of cases.4 The NCEPOD report also identified that nephrologists do not manage many patients suffering from AKI. Recently published National UK guidelines on AKI put emphasis on early identification of AKI and prompt investigation of patients5; therefore, increasing the awareness of AKI among non-nephrologists may help to improve outcomes.

However, there are currently several challenges facing postgraduate medical educators when they attempt to address the deficiencies in education and training. Introduction of the European Working Time Directive and the adoption of shift patterns6 have led to significant changes in the working patterns of trainee doctors.7 8 These changes have meant that delivering formal education programmes has become difficult.9 Adoption of newer technologies and improved collaboration between healthcare centres could enable pooling of resources to help educators develop better and more flexible educational approaches, which may overcome some of these barriers.

A review of education in primary care concluded that, in order to be effective, education resources should be multifaceted and sustainable10; equally, it is recognised that educational resources that are integrated within a clinical setting stand a higher chance of being successful than a standalone resource.11 As a consequence, we designed and developed a multifaceted educational intervention that aimed to improve the knowledge and awareness of AKI within an acute secondary care National Health Service (NHS) environment. Educators and clinicians at the University Hospitals of Leicester (UHL) and Royal Derby Hospital (RDH) collaborated over a period of 12 months to develop the intervention.

Objectives

The aims of this project were:

To assess the baseline knowledge and confidence of clinicians in dealing with patients with AKI across two large NHS Trusts (UHL and RDH).

To determine whether a quality improvement (QI) initiative involving a multifaceted educational intervention led to an improvement in the knowledge and confidence of clinicians managing patients with AKI or an improvement in the standards of basic care for patients with AKI assessed using existing audit measures.

Methods

This study was conducted as a QI project. It is recognised that in a healthcare setting it is important to pilot new ideas in the clinical environment, reflect on what was learnt and plan any further changes required before proceeding to full implementation. We therefore report on the findings of our project, and how successful elements have been implemented beyond the project period.

Setting: Two large UK teaching hospitals, the Leicester Royal Infirmary site at the UHL and the RDH. The two hospitals serve a population of over 1.5 million, with two major Accident and Emergency departments. The educational intervention was focused on the acute medical admissions units at both sites, but the educational tools that were developed were made available to all clinicians at both hospital sites.

The project was conducted over a 12-month period between August 2011 and August 2012 to coincide with an academic year. The project was carried out as a QI initiative within the trusts; therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Participants

The educational intervention and resources were targeted towards clinicians of all grades at both trusts.

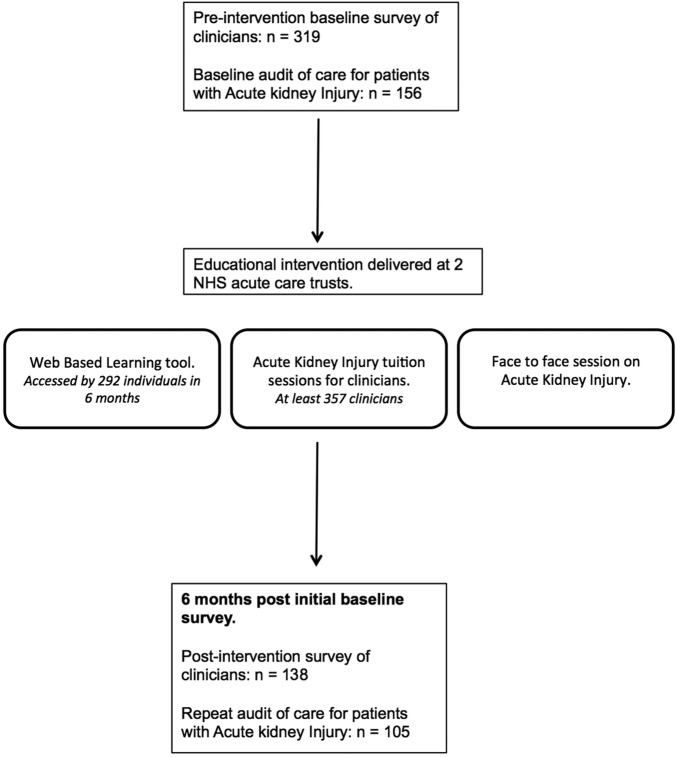

A flowchart demonstrating the process of the project is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the project process and evaluation.

Development of the intervention

The educational resources were designed and developed by the nephrology team, supported by two members of the Department of Clinical Education at UHL. All those involved in the project were involved in implementation of the educational package.

The intervention was multifaceted as described below to engage a range of learning styles and to be accessible by doctors working different shift patterns.

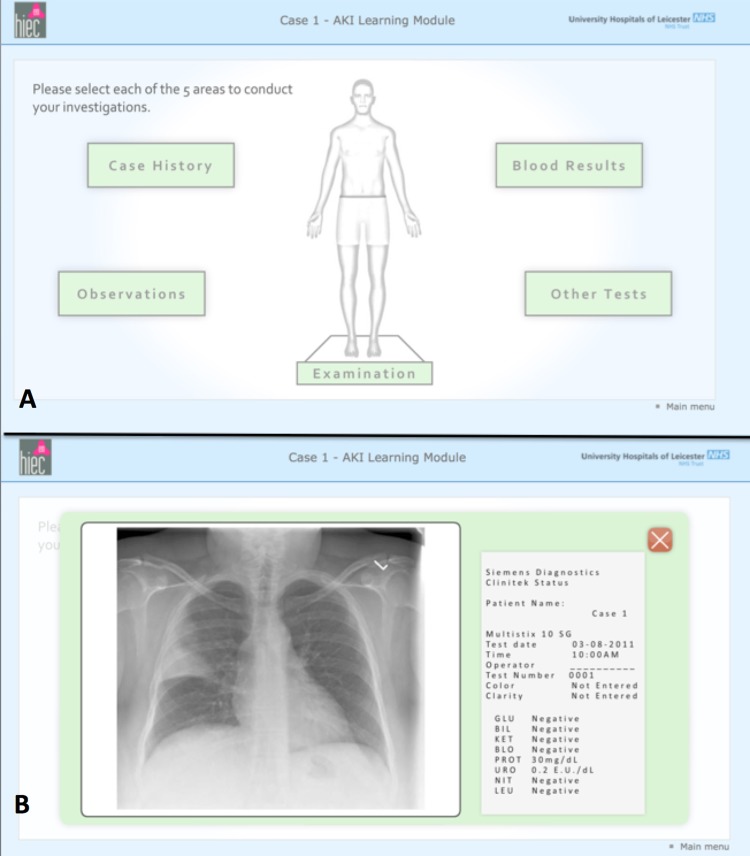

Web-based learning resource

The resource was developed based on realistic case studies, which aimed to highlight the issues identified in the 2009 NCEPOD report. Users were asked to work through clinical cases, which were designed to reflect how a case would unfold in clinical practice. The cases were designed to be easy to access and navigate as well as being very visual and interactive to maximise user engagement. To increase fidelity, where possible the graphics reflected what the user would see in everyday practice (eg, observation charts are shown in the same format as on the wards and blood test results are shown as they appear on screen within the hospital; figure 2). An email invitation was sent to all junior doctors at both hospital sites giving an electronic link to the resources. The resource was accessed via an electronic virtual learning environment (VLE) at UHL (http://www.euhl.nhs.uk). This allowed the project team to track the use of the web-based learning (WBL) resource. The VLE was accessible via any computer on the trust and also via the World Wide Web. The WBL itself was designed to run on any computer.

Figure 2.

Web-based learning resource on acute kidney injury. Each case is presented in a visually stimulating fashion and offers users a chance to systematically work through the case (A). Additional case information is presented in a real-life setting (B).

Integration of AKI education into established local education programmes

Education material for AKI was integrated into existing educational programmes across both Trusts. The teaching was delivered in a case-based fashion to increase engagement with participants. In total, 17 sessions were delivered to clinicians of all grades across both NHS Trusts in the 12 month period of the project.

Face-to-face teaching/feedback in clinical areas (FtF)

Members of the project team visited clinical areas where the majority of patients with severe AKI were located, and engaged the junior doctors in a discussion about their patients. This gave the project team a chance to provide direct face-to-face feedback and education about individual patient management.

Electronic alert tool for AKI

A validated electronic alert tool previously developed and implemented in RDH12 was introduced into the Leicester Royal Infirmary Acute Medical Unit to increase clinicians’ awareness of AKI.

Evaluation tools

An interactive questionnaire using Turning Point software (Turning Technologies, DA Hilversum) was utilised to evaluate the educational intervention. This allowed for the anonymous, accurate and quick collection of responses in real time using digital keypads given to participants before the start of the session.

A baseline questionnaire of knowledge and confidence of clinicians was performed before the educational intervention was launched using a short anonymous questionnaire developed by the project team. Clinicians were asked to reflect on their knowledge, confidence and self-reported practice when caring for patients with AKI using a five-point rating scale. Self-reported practice of clinical behaviour was recoded using a binary scale—with those responses of Almost always and Always coded as ‘Satisfactory practice’, and response of Often, Not very often, Rarely and Never coded as ‘Could improve’ to facilitate analysis and to reflect published guidance on AKI at the time of the project.13

The questionnaire also contained 15 ‘best of five’ multiple-choice questions (MCQs) to assess clinical knowledge of AKI (diagnosis, investigation and management). These were written by senior clinicians experienced in question writing and utilised the format used in the Royal College of Physicians examinations.14 The 15 MCQs on AKI clinical knowledge were remodelled for the postintervention questionnaire, but the questions were designed to test the same knowledge domains.

Eleven groups of doctors (N=357) participated in the baseline interactive questionnaire sessions that were conducted over a 4-week period at the start of the project. Following the implementation phase of the project, 148 doctors from the same cohort who had participated in the baseline surveys and been exposed to the intervention participated in six postintervention interactive questionnaire sessions over a 4-week period. Owing to the time frame of the project, the project team surveyed fewer groups of doctors in the postintervention sessions.

Clinical audit data

To assess the potential impact of the project on clinical management of patients with AKI, clinical audits were conducted at the two hospitals taking part in the project. The audits were carried out in accordance with ‘best practice guidelines’ on AKI management, before and after the project period.5 13

At UHL, the notes of 24 patients who had developed AKI stage 3 in February 2011 were audited. This audit was repeated for 28 patients with AKI in July 2012, after the deployment of the educational interventions. At RDH, 132 sets of notes were audited in 2010, and 77 in 2012. Patients with all stages of AKI were included with an equal proportion of patients in each AKI stage. Data audited included the number of patients on whom a renal ultrasound scan was performed within 24 h of admission, and the number of patients receiving urinalysis within 24 h.

Patients with AKI were identified using a validated and automated electronic alert tool.12

Data analysis

For questionnaire data, an individual's entire responses were excluded from the data analysis where no data about their grade were provided. Where there was a non-response to an MCQ question on knowledge, the response was graded as ‘incorrect’.

Results from the preintervention and postintervention questionnaires were compared. Data were anonymised so that an individual doctor's improvement between the two samples could not be assessed. This precluded the number of doctors who completed both questionnaires from being determined.

The data were analysed using an SPSS V.16 (IBM Software, New York, USA). χ² Tests were used for categorical data collected and independent t tests were used to analyse continuous data sets. An α of 0.05 was deemed significant.

Results

Interactive questionnaire

In total, 357 doctors were invited to take part in a preintervention questionnaire. Of these, 319 provided full demographic data and their results were analysed. One hundred and forty-eight doctors from the same cohort of clinicians were invited to take part in the postintervention questionnaire; 138 completed the demographic data (table 1): the completion rate for each question ranged from 89% to 100%.

Table 1.

Breakdown of clinicians according to grades, comparison between preintervention and postintervention questionnaires

| Foundation year 1 doctors | Foundation year 2 doctors | Core trainee doctors | Specialist trainee doctors | Consultants | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention (n=319) | 127 | 73 | 58 | 44 | 15 | 2 |

| Postintervention (n=138) | 59 | 27 | 30 | 10 | 11 | 1 |

N=number of participating clinicians.

Ninety-four per cent of clinicians reported receiving previous teaching on AKI. The seniority of the clinician and exposure to previous AKI teaching was not related (χ²=0.69, p=0.4).

Reported awareness of local clinical guidelines on AKI increased significantly in the postintervention survey compared to the preintervention survey, 26% vs 64%, respectively (χ²=60.2, p<0.001).

There was a significant increase in the number of doctors reporting satisfactory practice in the diagnosis of patients with AKI following the educational intervention, 50% vs 68% (χ²=12.1, p<0.001). In addition, there was a significant increase in the number of clinicians reporting satisfactory practice when investigating patients with AKI, 48% vs 64% (χ²=9.5, p=0.002). However, although there was an increase in the number of clinician self-reporting satisfactory practice in clinical management of AKI between the preintervention and postintervention questionnaires, 65% vs 73%, this difference was not significant (χ²=2.5, p=0.1; figure 3). There was a trend towards improvement in clinicians’ overall scores in the 15 MCQs between the preintervention (mean=44% ± 17.6%) and postintervention questionnaires (mean=47.3%, ±17.3%, p=0.06).

Figure 3.

Comparison of coded questionnaire results preintervention and postintervention. Clinician behaviour in diagnosing patients with acute kidney injury (AKI) (A) and investigating patients with AKI (B). Comparison of mean scores for 15 questions on AKI, preintervention and postintervention. Clinicians with less than 24 months clinical experience showed significant improvement in mean scores (C).

To explore whether the self-reported changes in AKI investigation and diagnosis could be explained by increasing clinical experience among the doctors during the project period, we compared the baseline scores of Foundation year 2 doctors (12 months experience at the time the project began) with those of Foundation year 1 doctors at the end of the intervention period (12 months experience at the end of the study period). There was a difference in awareness of AKI guidelines, 18.8% vs 69.5% (χ²=33.46, p<0.001) when comparing Foundation year 2 doctors preintervention versus Foundation year 1 doctors postintervention. There was also a significant difference in the number of clinicians reporting satisfactory practice in the diagnosis of patients with AKI when comparing the two groups, 51.4% vs 79.3% (χ²=10.7, p=0.01), and a trend towards more clinicians reporting satisfactory practice in the investigation of patients with AKI, 35.7% vs 59.3% (χ²=7.17, p=0.07). There was no significant difference in the mean MCQ scores between the two groups, 43.3% vs 42.6% (p=0.178).

Clinical audit data

The medical records of a total of 52 patients with AKI stage 3 were audited at UHL at the beginning and end of the project. There was a significant increase in the number of patients who had a renal ultrasound scan performed within 24 h of admission following the educational intervention compared with the initial audit, 20.8% vs 53.6% (χ²=5.9, p=0.02). In addition, there was a tendency towards a greater percentage of patients who had evidence of urinalysis carried out following the intervention (58.3% vs 71.5%, χ²=1, p=0.3; table 2).

At RDH, notes of 209 patients with AKI of all stages were similarly audited. There was a trend towards a greater percentage receiving a renal ultrasound within 24-h postintervention compared to preintervention, 45.3% vs 54.2%, (p=0.3) after the educational intervention, 40.3% vs 57.1% (p=0.2) and a trend towards more patients having urinalysis performed (table 2).

Table 2.

Investigation of AKI in two centres

| Centre 1‡ |

Centre 2§ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention (%) | Postintervention (%) | Preintervention (%) | Postintervention (%) | |

| Urine dipstick | 58.3 | 71.5 | 40.3 | 57.1 |

| Renal imaging within 24 h | 20.8* | 53.6* | 45.3 | 54.2 |

Clinical audit data. (1) Preintervention n=24, postintervention n=28. AKI stage 3. (2) Preintervention n=132, postintervention n=77. AKI stage 2 and 3.

*p<0.001.

‡Leicester Royal Infirmary.

§Royal Derby Hospital.

AKI, acute kidney injury.

WBL resource

In total, 292 individuals accessed the WBL between March 2012 and August 2012 with an overall completion rate of 65%. Forty-six people who completed the WBL responded to an online questionnaire requesting feedback from the module. Eighty-seven per cent of those who completed the WBL felt more confident about managing AKI and 97% would recommend the WBL to others.

Following the initial presentations and positive feedback about the WBL, it has now been made more widely available to other trusts and can be accessed at: http://www.uhl-library.nhs.uk/aki/.

Discussion

At present, there is no clear evidence to demonstrate that a particular intervention is effective in improving outcomes for patients with AKI. A UK National Consensus meeting on AKI, ‘Management of acute kidney injury: the role of fluids, e-alerts and biomarkers’, was held at the Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh in 2012 to review the latest evidence on AKI and produced national guidance on how to improve care.15 One of the key themes identified at this meeting was that it is essential to ensure that basic elements of care are delivered well. This was also echoed in the recently published UK guidelines on AKI.5 15

Although this project was not a randomised intervention but rather a QI exercise, we have identified the potential benefit of a multifaceted structured AKI educational intervention in improving awareness on AKI, with improvements in self-reported clinical behaviours of non-specialist clinicians when dealing with patients with AKI being associated with a trend towards better clinical care.

This project identified that although 94% of clinicians had received previous AKI education, less than half reported that they would ‘always’ or ‘almost always’ investigate a patient with AKI and only 26% were aware of the local guidelines. Following the intervention, there was a significant increase in the number of clinicians who were aware of local guidelines (26% vs 64%), and there was a significant improvement in the self-reported clinical behaviour, particularly with respect to making a diagnosis and initiating investigations in a patient with AKI (figure 3). This was supported by an audit of medical records that demonstrated improvements in recognised markers for good clinical care as defined in the UK Renal Association guidelines13 (table 1).

The face-to-face teaching sessions were very successful, created engagement with clinicians and greatly increased awareness of AKI on the wards. However, the project team found that the sessions were time consuming and to be sustainable would require specific resources to be directed towards creating a routine nephrology/outreach nurse service.

The completion rate of the WBL was high compared to the reported completion rates of other non-compulsory WBL tools.16 The high completion rate was reflected in the positive feedback received about the WBL from users. However, despite heavy promotion of the WBL by email and on hospital intranet computer login in-screens, there was a low rate of uptake among clinicians as a whole. The reason for this is not entirely clear, but suggests that clinicians still prefer to engage with more traditional forms of teaching, and WBL should not be seen as a replacement for other forms of education.

An important aspect of the project was to develop teaching resources that are sustainable. Since the end of the project, additional sessions on AKI have been incorporated into the hospitals’ routine education programme, including regular teaching sessions on AKI for Foundation year 1, Foundation year 2 and core medical trainee doctors on an annual basis. Grand round presentation to raise awareness of AKI has taken place annually since the end of the project, and the WBL continues to be promoted. We hope that as more clinicians are exposed to these educational resources, we will be able to demonstrate improved clinical outcomes in the future.

Limitations

It is recognised that evaluating the effects of QI projects is difficult,17 and there were several potential confounders in this study.

Environment

In a complex, acute care NHS environment, there are multiprofessional teams caring for patients, and patients will encounter many different doctors and nurses during an inpatient hospital stay.18 As a consequence, it is difficult to clearly define the impact of an educational intervention on a cohort of doctors’ knowledge and confidence and the impact of this on patient care and outcomes.

Clinicians’ previous experience

We could not control for the variation in doctors’ prior learning and experience and the fact that during the course of an academic year an individual doctor’s overall experience in managing patients of all types will inevitably increase. However, following this intervention, Foundation year 1 doctors (12 months experience) reported that they were more aware of AKI compared to doctors who had accrued 12-month experience at the beginning of the study (baseline Foundation year 2 doctors). There were no differences in the mean MCQ scores between the two groups, but it is recognised that MCQs assess knowledge rather than skill or performance.19 Although self-reported performance is not always an indicator of good clinical care,20 there was a clear change in self-reported behaviour postintervention suggesting increased awareness of AKI. This suggests that even in this complex acute care environment the educational intervention did increase awareness of AKI among junior doctors, who are often the first cohort of clinicians to manage patients with AKI.4

Poor response rate to the postintervention questionnaire

There was a discrepancy between the number of physicians who took part in the baseline and postintervention questionnaires. In order to study a complete academic year, the evaluation phase of the project was conducted in July (at the end of Foundation years 1 and 2). However, a high proportion of doctors from the cohort was unavailable to take part in the evaluation because they were on annual leave at that time. Consequently, this further reduced the number of doctors who could leave clinical duties to engage in the evaluation due to the reduced staffing numbers on the wards. Although the numbers were reduced, which could lead to bias, the doctors sampled were from within the same cohort, and there was no significant difference in the demographics of the physicians questioned or the completion rate of the two questionnaires.

Studying the impact of an educational intervention in the acute NHS setting will always be confounded by variables that cannot be controlled, but despite these limitations, the results of the project demonstrated that, in principle, a well-designed multifaceted educational intervention deployed in a real NHS acute clinical setting can be effective in raising knowledge and awareness about important clinical conditions like AKI.

As this was a QI project, we reflected on the data gathered to inform system wide changes to the way AKI education is delivered. As already described, both trusts now have sustainable educational resources on AKI that blend traditional education sessions with newer technologies such as the WBL.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other literature

A recently published single centre study from Ulster21 used a checklist approach in conjunction with an educational programme to increase awareness of AKI. Through engagement with clinical staff on the ward, and recognition that changes to practice required a gradual stepwise approach, the team was able to increase recognition of AKI and increase the completion rate of the AKI checklist.

Our project had similar aims but was conducted on a larger scale and implemented across two large NHS acute Trusts. We were aware that junior clinicians in particular rotate around different clinical environments every 4 months. In order to be compatible with different learning styles, working patterns and previous clinical experience, our educational intervention consisted of a variety of different educational tools in an attempt to maximise clinician engagement. We also chose to evaluate outcomes by directly questioning clinicians about their self-reported confidence and setting an objective knowledge assessment as well as auditing clinical outcomes rather than using a checklist approach. Our findings build on the findings of the Ulster group. Our project includes data on clinicians’ self-reported practice, demonstrating increased awareness of local guidelines, a trend towards higher knowledge scores, as well as using audit data to demonstrate a trend in improving clinical practice following educational intervention across the two different hospitals.

Unanswered questions and future research

In the future, it will be important to test the sustainability of this type of intervention and to collect data in a larger cohort of patients on clinical outcomes including patient length of stay and mortality. Furthermore, an ongoing study into the success of different educational approaches among different groups of healthcare professionals is also warranted to ensure that any resources developed maximise their educational impact. Finally, the majority of patients are admitted to hospital with AKI rather than developing it de novo after admission. Future work is required to look at the potential impact of a similar intervention aimed at improving the knowledge about managing AKI in a primary care setting.

Conclusions

We have reported a QI project that aimed to assess the impact of an educational intervention in improving awareness of AKI in non-nephrologists. Despite the acknowledged limitations to the study, the self-reported behaviour of non-specialist clinicians when dealing with patients with AKI improved after the intervention and there was a trend towards improved clinical care from clinical audit data. Our findings suggest that standalone educational packages such as electronic learning resources should not be seen as a replacement for more traditional ‘face-to-face’ forms of postgraduate education; however, new technologies can be successfully integrated with more traditional teaching programmes to help overcome some of the barriers that face postgraduate medical educators.

The project was delivered successfully in two large teaching hospitals and large elements have been sustainable beyond the end of the project period. This project demonstrates the power of QI projects in helping to initiate changes in practice. However, this project was not a randomised intervention; therefore, the results are subject to bias and the findings need to be validated in a more formal research setting.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GX, RB, RW, NS, SC were all involved in substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data/analysis/interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This project was supported by a grant from the East Midland Health Innovation Education Cluster. The Turning point surveys were supported by Mrs Joanne Kirtle, Education Quality Manager and Mr James Trew, Learning Technologist, University Hospitals of Leicester.

Competing interests: GX had financial support from East Midland Health Innovation Education Cluster for the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ali T, Khan I, Simpson W, et al. Incidence and outcomes in acute kidney injury: a comprehensive population-based study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:1292–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolhe NV, Stevens PE, Crowe AV, et al. Case mix, outcome and activity for patients with severe acute kidney injury during the first 24 hours after admission to an adult, general critical care unit: application of predictive models from a secondary analysis of the ICNARC Case Mix Programme database. Crit Care 2008; 12(Suppl 1):S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart JM. Adding insult to injury: a review of the care of patients who died in hospital with a primary diagnosis of acute kidney injury (acute renal failure): a report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (2009). London: National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacLeod A. NCEPOD report on acute kidney injury-must do better. Lancet 2009;374:1405–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Acute kidney injury: NICE Guidance CG169. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health D. Hours of work of doctors in training: the New Deal. London: Department of Health, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lancet Doctors’ training and the European Working Time Directive. Lancet 2010;375:2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickersgill T. The European working time directive for doctors in training. BMJ 2001;323:1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Temple J. Time for training: a review of the impact of the European Working Time Directive on the quality of training, 2010

- 10.Cantillon P, Jones R. Does continuing medical education in general practice make a difference? BMJ 1999;318:1276–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coomarasamy A, Khan KS. What is the evidence that postgraduate teaching in evidence based medicine changes anything? A systematic review. BMJ 2004;329:1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selby NM, Crowley L, Fluck RJ, et al. Use of electronic results reporting to diagnose and monitor AKI in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;7:533–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewington A, Kanagasundaram S.2011. Acute kidney injury; renal association guidelines. Secondary acute kidney injury; renal association guidelines. http://www.renal.org/clinical/guidelinessection/AcuteKidneyInjury.aspx.

- 14.Boards IS. ISB & JCB MCQ question development. Secondary ISB & JCB MCQ question development 2012. http://www.intercollegiate.org.uk/content/content.aspx?ID=5

- 15.Christie B. Get basics right to improve acute kidney injury, says consensus conference. BMJ 2012;345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadley J, Kulier R, Zamora J, et al. Effectiveness of an e-learning course in evidence-based medicine for foundation (internship) training. J R Soc Med 2010;103:288–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schouten LMT, Hulscher MEJL, Everdingen JJEv, et al. Evidence for the impact of quality improvement collaboratives: systematic review. BMJ 2008;336:1491–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trebble TM, Hansi N, Hydes T, et al. Process mapping the patient journey through health care: an introduction. BMJ 2010;341:394–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med 2007;356:387–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, et al. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:1094–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forde C, McCaughan J, Leonard N. Acute kidney injury: it's as easy as ABCDE. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2012;1:u200370.w326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.