Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS) in which myelin becomes the target of attack by autoreactive T cells. The immune components of the disease are recapitulated in mice using the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model. EAE is classically induced by the immunization of mice with encephalitogenic antigens derived from CNS proteins such as proteolipid protein (PLP), myelin basic protein (MBP) and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG). Immunization of susceptible mouse strains with therse antigens will induce autoreactive inflammatory T cell infiltration of the CNS. More recently, the advent of clonal T cell receptor transgenic mice has led to the development of adoptive transfer protocols in which myelin-specific T cells may induce disease upon transfer into naïve recipient animals. When used in concert with gene knockout strains, these protocols are powerful tools by which to dissect the molecular pathways that promote inflammatory T cells responses in the central nervous system (CNS). Further, myelin-antigen-specific transgenic T cells may be cultured in vitro under a variety of conditions prior to adoptive transfer, allowing one to study the effects of soluble factors or pharmacologic compounds on T cell pathogenicity. In this review, we describe many of the existing models of EAE, and discuss the contributions that use of these models has made in understanding both T helper cell differentiation and the function of inhibitory T cell receptors. We focus on the the step-by-step elucidation of the network of signals required for T helper 17 (Th17) cell differentiation, as well as the molecular dissection of the Tim-3 negative regulatory signaling pathway in Th1 cells.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, CD4+ T lymphocyte, myelin, interleukin-17, Sgk1, Tim-3, Bat3

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic, debilitating neurologic disorder characterized pathologically by central nervous system (CNS) white matter inflammation, demyelination and, in cases of chronic disease, astroglial scarring. The formation of demyelinated lesions leads to axonal injury and neurological deficit [1]. While the precise mode of disease etiology remains elusive, it is widely believed that MS pathology is initiated by the infiltration of autoreactive T cells into the CNS and subsequent immune attack on CNS myelin. The immune hypothesis of MS pathology is supported by the near-uniform presence of T cells, B cells and macrophages in MS plaques [1]. Evidence from the clinic also supports a central role for the immune system in MS disease course: glatiramer acetate, natalizumab and interferon-beta, all of which modulate the immune response, are front-line therapies [2].

MS is a highly prevalent disease, with rates of incidence estimated at between 177 to 350 per 100,000 in the United States and Canada [3], and as a result has been the subject of intensive research. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is an umbrella term referring to multiple different models of CNS autoimmunity in vertebrate animals. Besides rats and mice, these have included species as diverse as non-human primates [4] and guinea pigs [5]. However, the bulk of the literature has centered on the study of CNS autoimmunity in rats and mice, with the latter being the focus of this review. Use of these models has greatly expanded our insight into the mechanisms that are responsible for MS pathology. EAE models have also allowed us to gain broad insight into the function of delayed type immune responses in general, and inflammatory T cell responses to CNS myelin in particular. In this review, we will describe the various mouse models of MS and their characteristics. In addition, we will highlight some key advances in our understanding of autoimmune pathology that have resulted from studies using EAE.

Clinical history of MS

Aspects of the pathology of MS were described as early as the mid-1800’s with Cruveilhier in particular noting the existence of MS lesions in the CNS [6]. However, the first comprehensive description of the disease was provided in the 1860’s by Charcot, who emphasized the requirement of multiple distinct attacks in the proper characterization of MS [7, 8]. Indeed, MS must be distinguished clinically from acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), an idiopathic condition of acute central nervous system inflammation. The critical unit of diagnosis is a neurologic event and its subsequent resolution [9]. The McDonald criteria for the diagnosis of MS define a neurologic event as being an attack that lasts at least 24 hours, with subsequent attacks having to occur at least 30 days after the preceding attack in order to be considered separate events [10].

With this definition in mind, it is possible to classify subtypes of MS pathology on the basis of disease course. Approximately 85% of patients initially present with a relapsing-remitting disease course (RR-MS), in which clearly defined, repeated, attacks are followed by remissions. There may or may not be cumulative neurological deficit upon remission, and this pattern may last for years. However, of these patients, about 50% will transition to a secondary progressive form in which disease-associated deficits accumulate without relapse. Approximately 15% of total patients present a primary-progressive course in which disease worsens progressively after the initial attack, without remission [11].

While developing a single model of EAE that encompasses the full spectrum of MS symptoms remains a challenge, individual models of EAE are able to recapitulate specific elements of MS pathology. Models of active immunization and passive transfer in the SJL/J, C57BL/6 and NOD strains will be the focus of this review.

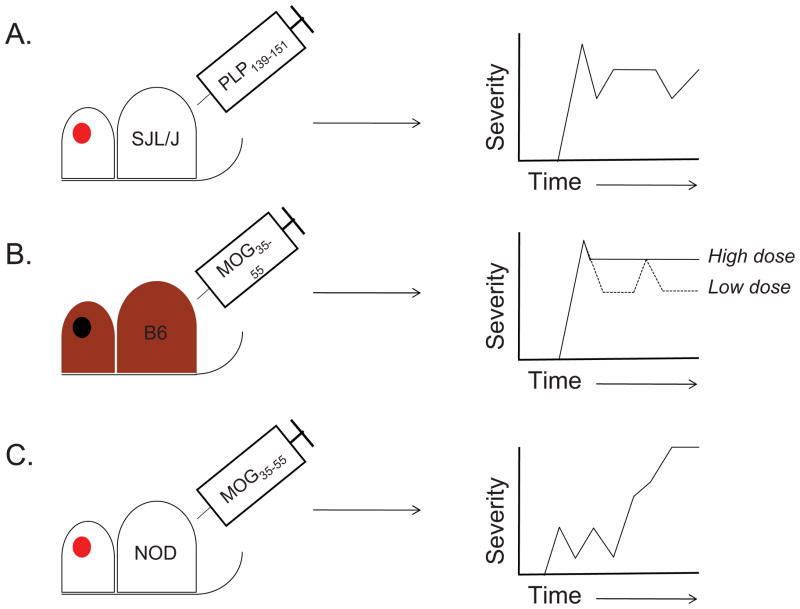

Relapsing EAE (R-EAE) in the SJL/J strain

EAE may be induced in mice through either active immunization with protein or peptide, or by passive transfer of encephalitogenic T cells. In either case, the relevant immunogen is derived from self-CNS proteins such as myelin basic protein (MBP), proteolipid protein (PLP) or myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG). Immunization of SJL/J mice with the immunodominant epitope of PLP (PLP139-151), induces a relapsing-remitting disease course [12], while disease induced by the immunodominant MOG35-55 peptide in C57BL6/J mice tends to be of a chronic nature [13] (Figure 1). Classic EAE is characterized by an ascending paralysis beginning at the tail [14], followed by hind limb paralysis and forelimb paralysis and is assessed semi-quantitatively using a 5-point scale [15–17]. In some cases, an “atypical” form of EAE is seen. This is particularly the case when models of adoptive myelin-reactive T cell transfer are used. Atypical EAE, which is also scored using a 5-point scale, is characterized less by muscular paralysis and more by ataxia and loss of co-ordination [18].

Figure 1. Variations in EAE disease course upon active immunization with encephalitogenic peptides.

A. The immunization of SJL/J mice with PLP139-151 can result in an initial paralytic attack, followed by multiple remissions and relapses [24]. B. Immunization of C57BL6/J mice with a high dose of MOG35-55 causes a chronic disease course in which an initial attack does not resolve (solid line) [17, 33]. By contrast, immunization with a low dose of MOG35-55 can induce either a multiphasic relapsing-remitting disease course (dotted line) or a single attack followed by a single remission (not shown) [17]. C. Immunization of NOD mice with MOG35-55 results in a series of mild attacks/relapses followed by remissions. The disease ultimately transitions into a secondary chronic phase that is reminiscent of the secondary progressive phase of MS [56].

Although much early work was done in guinea pigs and rats, by the early- to mid-eighties, mice began to be extensively used as a model for EAE. Using both MBP-derived peptides and MBP-reactive T cell clones, Zamvil et al. were able to induce EAE in SJL/J and PL/J mice [19]. They later demonstrated that an acetylated N-terminal-derived peptide from MBP was sufficient to induce EAE in PL/J mice [20]. These initial studies seemed to indicate that MBP was the most relevant source of encephalitogenic antigen in the CNS. At around the same time, Miller and colleagues were able to induce a relapsing EAE disease course in SJL/J mice by immunizing them with syngeneic mouse spinal cord homogenate. Notably, in vivo clearance of CD4+ T cells through use of L3T4 monoclonal antibody resulted in a dramatic reduction in disease severity [21], as could depletion of TcR Vβ2-expressing T cells thought to be largely specific to PLP [22]. These findings pointed to a role for CD4+ T cells in disease.

Initial studies suggested that MBP is the only encephalitogenic protein that could induce EAE, and that disease induced by spinal cord homogenate and other myelin antigens, including PLP, was due to contamination with MBP. However, subsequent studies demonstrated that SJL/J mice could be tolerized to spinal cord homogenate via pre-treatment with purified PLP, but not MBP, protein [23]. Furthermore, induction of EAE could be induced by synthetic myelin PLP139-151, which had no homology to MBP, further strengthening the concept that multiple myelin proteins may have the ability to induce EAE. PLP139-151 was identified as an immunodominant epitope for the induction of EAE in the SJL strain [24, 25], and the first clinical signs of disease could be noted 12–18 days after a single immunization. More than half of immunized mice showed signs of relapse after recovery from the initial attack (Figure 1A). Notably, R-EAE could also be induced through the passive transfer of PLP139-151-reactive T cell lines and clones to naïve hosts. Passive transfer resulted in a mixture of disease courses, with some animals developing monophasic disease and others showing a pattern of remission and relapse [15]. Additional studies found evidence of epitope spreading in the R-EAE model. Mice immunized with PLP139-151 developed splenic lymphocyte responses to PLP178-191, and these PLP178-191-reactive T cells could induce EAE upon adoptive transfer. Further, SJL/J recipients of T cells reactive to encephalitogenic peptide MBP84-104 displayed delayed type responses when challenged with PLP139-151 [24], and PLP178-191-driven EAE can result in activation of PLP139-151-reactive T cells in the CNS of diseased animals [26]. These findings are particularly intriguing given evidence of autoantigenic heterogeneity in MS [27].

Classic models of adoptive transfer involve the immunization of donor mice with PLP-derived peptides, isolation of peripheral lymphoid cells after 7 to 10 days of culture, in vitro restimulation and subsequent transfer to naïve recipients. While providing proof of the central role of CD4+ T cells to pathogenesis, these models suffer from several limitations. While peripheral lymph node cells are restimulated with specific antigen (such as PLP139-151) prior to transfer, the population is essentially polyfunctional. This makes it difficult to isolate the contribution of T cells directed against a specific antigenic epitope. Further, the encephalitogenic capacity of transferred T cells necessarily reflects the in vivo condition in donor animals. The decreased ability of knockout T cells to transfer disease could, for example, reflect defective antigen presentation in the donor animals rather than result from lesions in T cell function. This, combined with the pleiotropic nature of immune gene expression, makes it difficult to use these adoptive transfer models to isolate the contributions of individual genes to encephalitogenic T cell function.

The development of T cell receptor (TcR) transgenic mouse models in over the past 20 years has greatly facilitated the study of antigen-specific T cell responses. The TcRα- and β-chains specific for a given epitope are expressed in the mouse germline. As they express a functional TcR, the T cells from the resulting transgenic animals escape Rag1- or Rag2-mediated recombination of their TcR loci and express transgenic TcRs at a very high frequency. T cells from TcR transgenic mice can be >95% specific for a defined epitope that may be either ectopic or self-derived [28]. MBP Ac(1-11) specific TcR transgenic mice were the first to be generated, and were shown to develop spontaneous paralytic disease on the PL/J and B10.PL backgrounds [29]. More recently, we have exploited TcR transgenic technology to generate 2 TcR transgenic mouse lines on the SJL/J background (5B6 and 4E3) that are specific for PLP139-151. Both strains develop spontaneous EAE at a high frequency, and we were unable to maintain the 4E3 stain on the SJL/J background past the 5th generation because of spontaneous EAE in the progeny. 5B6 animals display infiltration of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells into both the meninges and CNS parenchyma [30]. More recently, Wekerle et al. have generated a MOG92-106-specific TcR transgenic line (TCR1640) that develops spontaneous R-EAE on the SJL/J background [31].

However, studying specific genes and pathways on the SJL/J or PL/J backgrounds turned out to be quite challenging, because of the emergence of the C57BL/6J (B6) strain as the preferred background for the generation of gene knockout animals. To study the effect of gene deletions on the SJL/J or PL/J strains would thus require extensive and time-consuming backcrosses. This led to the search for an appropriate EAE model on the C57BL/6J background.

EAE models of active MOG peptide immunization on the C57BL/6J background

The relative ease of transgenesis and genetic ablation in the C57BL/6J (B6) strain has made it the de facto strain of choice for studying immune and autoimmune responses [32]. Thus, there was great interest in developing models of EAE in H-2b-restricted animals, as this would facilitate the study of how individual genes and molecular pathways affect disease progression. In an important initial study, Ben-Nun and colleagues [33] studied the ability of multiple MOG-derived peptides to induce EAE in B6 mice. While several peptides could induce T cell responses upon ex vivo restimulation, only MOG35-55 was able to induce CNS autoimmunity upon immunization. While this study reported that pertussis toxin (PT) could enhance disease onset and severity but was not absolutely required, concominant administration of PT is now commonly used in conjunction with this model. Importantly, it was reported that MOG35-55 induced a chronic form of the disease that did not remit [33] (Figure 1B). While this observation has been independently corroborated [13], it is also possible that the dose of MOG35-55 peptide can influence the course of disease. Berard et al. [17] have reported that while a relatively high dose of peptide and adjuvant (300 μg MOG35-55, 4 mg•ml−1 of M. tuberculosis extract in adjuvant, 300 ng PT) induces chronic non-remitting EAE in B6 mice, lower doses of peptide/adjuvant (50 μg MOG35-55, 0.5–1 mg•ml−1 M. tb., 200 ng PT) can promote a relapsing-remitting disease course (Figure 1B). These findings suggest that careful titration of peptide and dosage under specific environmental conditions may be required in order to standardize the type of disease seen upon MOG35-55 immunization.

In the years following the development of the MOG35-55 EAE model, a synergy emerged between use of this system and the new abundance of gene knockout strains. This allowed for a number of studies on the role of individual immune factors in regulating autoimmune responses against CNS myelin, including cytokines [34–36], T cell surface receptors [37, 38], signaling molecules [39] and transcription factors [40]. Several studies used knockout strains to elucidate the contribution of entire cell types to MOG35-55-induced EAE such as B cells [41], CD11c+ monocytes [42], CD8+ T cells [43] and γδ T cells [44].

MOG35-55-driven EAE has also permitted analysis of the role that CD8+ T cells play in CNS autoimmunity. Accumulating evidence suggests that CD8+ T cells have a role in MS pathology. CD8+ T cells outnumber CD4+ T cells in MS lesions by as much as 10 to 1 [45], and CNS antigen-reactive T cells can be readily detected in the peripheral blood of MS patients [46]. Taken together, these data suggest that CD8+ T cells proliferate in response to myelin antigens, and can traffic to sites of inflammation in the context of CNS autoimmunity. Ford and Evavold [47] isolated peripheral immune cells from MOG35-55-immunized mice, restimulated them with peptide, and then adoptively transferred sorted CD8+ T cells into recipient animals. They found that MOG35-55-specific CD8+ T cells were as capable of inducing EAE in naïve recipients as their CD4+ counterparts. As CD8+ T cells respond to 10–14mer peptides presented by MHC class I molecules [48], the authors reasoned that there was a core CD8+-reactive epitope contained with amino acids 35–55 of MOG. Indeed, they were able to identify MOG37-46 as a minimal peptide that can induce specific CD8+ T cell responses in B6 mice.

Transgenic T cell models of MOG-driven EAE

2D2 transgenic mice

Much as had been the case for EAE research in the SJL/J strain, there was an emerging need to generate TcR transgenic models of MOG-driven EAE that could allow one to study the contribution of specific genes to T cell driven CNS autoimmunity. While T cell or bone marrow transfers into, and subsequent peptide immunization of, immunodeficient strains can yield important insights [16], such an approach is cumbersome. Our group has developed a class II-restricted TcR transgenic model to study MOG35-55-driven EAE. An epitope-reactive T cell clone (2D2) was isolated from MOG35-55-immunized B6 mice and its α- and β-chains were knocked in to the B6 germline by transgenesis [49]. The resulting 2D2 T cells are Vα3.2+ and Vβ11+, and react specifically to MOG35-55. Peptide immunization of 2D2 mice resulted in more severe EAE than in nontransgenic littermate controls, and surprisingly, a low percentage (~4%) of 2D2 transgenic animals develop spontaneous EAE,

Intriguingly, a high percentage of 2D2 animals (>30%) develop spontaneous optic neuritis (ON), an inflammatory disease of the optic nerve that frequently results from inflammation and demyelination of the nerve [49]. Isolated ON is frequently an early symptom of MS [50]. Immunization of 2D2 mice with a suboptimal dose of MOG35-55 resulted in a high frequency of optic neuritis yet no signs of classical EAE.

Wekerle and colleagues had previously described a B cell heavy chain knock-in mouse strain (IgHMOG; also known as TH) that contains a high frequency of anti-MOG antibody-secreting B cells in the peripheral repertoire. Upon active immunization with recombinant MOG, IgHMOG animals develop EAE at a higher frequency than do nontransgenic littermates [51]; however, the mice never develop spontaneous EAE, emphasizing the need for myelin-specific T cell expansion in the periphery in order for disease to progress. The logical next step was to exploit the availability of the 2D2 and IgHMOG strains to determine the effect of MOG specificity of both B cells and CD4+ T cells in the same animal. While IgHMOG animals do not develop spontaneous EAE [51] and 2D2 mice only develop EAE at a low frequency [49], a high frequency of IgHMOGx2D2 mice (over 60%) display spontaneous EAE. Histologically, the disease in these animals is characterized by the presence of inflammatory lesions in the spinal cord and optic nerve, and also by the relative sparing of the brain from inflammation. This histopathological pattern is reminiscent in some, but not all, respects to human Devic’s disease/neuromyelitis optica (NMO) [52, 53], a type of CNS inflammation that is distinct from classical MS and that is prevalent in Asian populations [54]. Taken together, these findings indicate that the 2D2 model may provide a flexible platform by which to study multiple phenotypes of clinical MS [49].

Additionally, the generation of the 2D2 strain created the possibility that clonally homogenous MOG-specific T cells could be stimulated in vitro under a variety of conditions prior to adoptive transfer. In earlier adoptive transfer models of EAE, T cells were isolated from primed peptide-immunized mice, restimulated ex vivo with specific antigen, and transferred to hosts [15]. These models, while useful, carry several distinct disadvantages. Notably, the clonal heterogeneity of these T cell populations made it impossible to ensure that the transferred cells were entirely specific to the antigen in question. Further, in vivo crosstalk between different cell types during priming made it difficult to isolate the effects of various treatments and gene deletions on T cell pathogenicity. Finally, peptide immunization gives rise to multiple T helper cell lineages in vivo, making it challenging to isolate the contribution of specific T cell subsets to disease. Jäger et al [55] developed a model in which 2D2 T cells are stimulated in vitro, prior to transfer, in the absence of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Naïve (CD62Lhi) 2D2 CD4+ cells are first purified using fluorescent label-assisted cell sorting (FACS) techniques. They are then stimulated in vitro using antibodies to CD3 and the costimulatory ligand CD28. As 2D2 T cells are clonally specific for MOG35-55, one can be certain that the activated cells are directed against the target antigen. Cells are then transferred to naïve host animals. The study’s focus was on the capacity of different T helper subsets to induce EAE. To this end, in vitro stimulated 2D2 T cells were cultured with various combinations of cytokines and blocking antibodies to generate Th1, Th2, Th17 and Th9 subsets. Intriguingly, we were able to show that Th1, Th17 and Th9 cells each induce EAE with distinct pathologic signatures [55]. Further, this transfer model provides an ideal system by which to study the effects of pharmacological compounds on T cell-driven CNS autoimmunity. As the 2D2 T cells are activated in the absence of APCs, the effect(s) of the compound(s) in question will be only directed towards MOG35-55-reactive T cells.

1C6 transgenic mice

It has been known for some time that the NOD strain mice, which develop diabetes spontaneously, are susceptible to EAE upon active immunization with MOG35-55. Further, these animals display a relapsing-remitting disease course that is followed by a chronic non-remitting stage [56], very similar to what is observed in human MS (Figure 1C). As a significant number of MS patients transition from RR-MS to a secondary progressive phase of disease [57], the EAE course seen in NOD mice renders it a highly attractive model with which to recapitulate human pathology. We therefore set out to generate a CD4+ TcR transgenic model for MOG35-55-driven EAE on the NOD background, in much the same manner that we had previously generated the 2D2 transgene on the B6 background. Surprisingly, the resulting mice (named 1C6) possessed both CD4+ and CD8+ MOG35-55-reactive T cells. The 1C6 model was thus the first to produce MOG-reactive transgenic CD8+ T cells, and provided a unique opportunity to study the role of CD8+ T cell-mediated EAE [58]. We transferred purified 1C6 CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, or both, to lymphocyte-deficient NOD. Scid and immunized them with MOG35-55. All three groups developed EAE, though mice receiving 1C6 CD8+ T cells alone developed disease at a lower incidence and of lessened severity [58].

1C6 mice were then crossed to the IgHMOG strain to generate, for the first time, a strain in which the three major lymphocyte subtypes bore antigenic specificity for the same CNS antigen. In contrast to 1C6 animals, IgHMOGx1C6 mice developed EAE at a high frequency (>60%); further, in contrast to IgHMOGx2D2 mice [53], IgHMOGx1C6 mice displayed classic EAE rather than Devic’s-like pathology, with the majority of inflammatory lesions seen in the spinal cord [58]. Thus, the 1C6 strain allows one, for the first time, to study the interplay between MOG-specific CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells and B cells in the same mouse strain.

Key insights derived from use of EAE models

Role of the Th17 subset in EAE

Over 20 years ago, Mosmann and Coffman first described two subtypes of T helper cells that could be discriminated on the basis of cytokine production. T helper 1 (Th1) cells were shown to produce interferon (IFN)γ [59], while Th2 cells were described as producing interleukin (IL)-3, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 [59–61]. The Th1/Th2 paradigm soon came to dominate our understanding of effector CD4+ T cell responses. Th1 cells were shown to clear intracellular pathogens, while Th2 cells were shown to clear extracellular pathogens and parasitic infections [62]. In the context of autoimmunity, Th1 responses were thought to promote pathology while Th2 responses were thought to inhibit it [63].

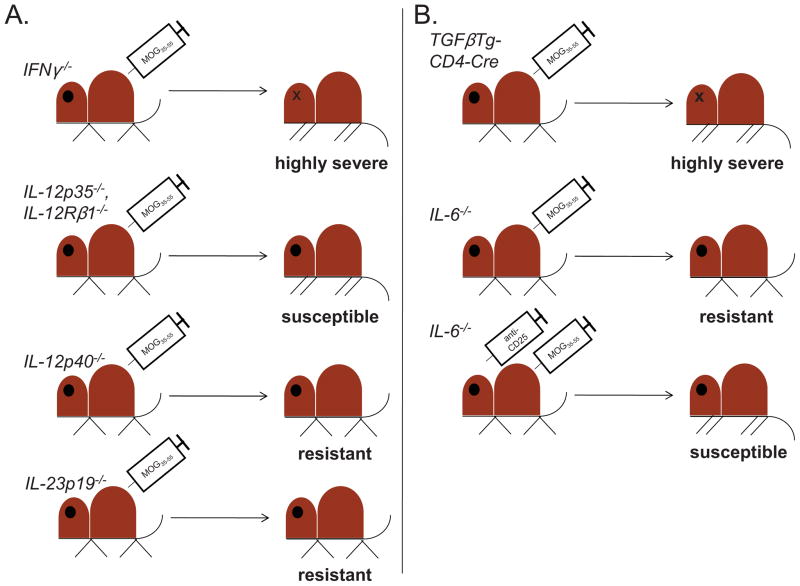

A series of initial studies showed that myelin-specific Th1, but not Th2, cells were capable of inducing EAE upon adoptive transfer. These findings, coupled with the expression of the benchmark Th1 cytokine IFNγ in CNS lesions in EAE, helped construct the paradigm of EAE being a Th1-mediated disease. However, subsequent studies showing that mice deficient in IFNγ develop highly severe EAE proved an inconvenient truth in light of the Th1/Th2 paradigm [64–66]. These findings were in contrast to the resistance to EAE of IL-12p40−/− mice, which lack one subunit of the key Th1 differentiation factor IL-12 [67].

This Gordian knot began to be severed by the discovery of the cytokine IL-23, a heterodimer consisting of the p40 subunit of IL-12 with a novel p19 subunit [68]. The resistance of IL-12p40−/− mice to EAE could thus be reinterpreted to demonstrate a critical role for IL-23, and not IL-12, in EAE. Indeed, IL-12p35−/− [67, 69, 70] and IL-12Rβ2−/− [71] mice, which solely lack IL-12 mediated signaling, were susceptible to MOG35-55 driven EAE, while IL-23p19−/− mice were resistant [70]. Thus, findings from work on the EAE model now hinted at the existence of a distinct T helper subset, potentially induced by IL-23, that could promote autoimmunity (summarized in Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Use of MOG35-55-driven EAE in gene knockout strains to identify a role for Th17 responses in CNS autoimmunity.

A. IL-23-driven, and not IL-12-driven, responses are essential for EAE pathology. IFNγ−/− mice develop highly severe disease (top panel), despite the role of IFNγ as the key Th1 cytokine [64–66]. Further, IL-12p35−/− [67, 69, 70] and IL-12Rβ1−/− [71] mice, which specifically lack signaling through the Th1-differentiating cytokine IL-12, are susceptible to EAE (second panel), while IL-12p40−/− mice, which lack IL-12 and IL-23 expression, are resistant [67] (third panel). Importantly, IL-23p19−/− mice, which lack IL-23 exclusively, are also resistant to EAE [70] (fourth panel). These studies collectively demonstrate a role for the Th17-promoting cytokine IL-23 in EAE pathogenesis. B. Role of TGFβ and IL-6 in promoting EAE. TGFβTg-CD4 Cre mice, which ectopically express TGFβ in CD4 + T cells, develop highly severe EAE in comparison to control animals [75] (top panel). Further, while IL-6−/− mice are relatively resistant to EAE (second panel), disease severity increases, and Th17 responses are restored, when CD25+ Tregs are depleted in vivo (bottom panel) [79]. These findings indicate that TGFβ and IL-6 co-operate to promote Th17 responses, and that IL-6 does so in part by suppressing the activity of Tregs.

Further EAE studies identified a critical role for the inflammatory cytokine IL-17, and IL-17-producing T cells, in IL-23-mediated autoimmune pathogenesis. CNS-infiltrating T cells produced IL-17, yet corresponding T cells from IL-23p19−/− mice did not. Further, in vivo blockade of IL-17 [72, 73], but not IFNγ [73], reduced the severity of EAE. It is important to note that Th1 responses are capable of driving CNS autoimmunity; transfer of Th1 differentiated 2D2 T cells to naïve hosts induce robust EAE [55].

Accumulating evidence therefore suggested that much as IL-12 drives Th1 cell generation, IL-23 must be the differentiating factor for IL-17-producing T cells (Th17 cells) that could promote CNS autoimmunity. However, naïve T cells do not express IL-23 receptor (IL-23R) [74], and are poorly responsive to IL-23 [68]. In addressing this issue, our group found that IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells (Th17 cells) differentiated in the presence of two cytokines, transforming growth factor (TGF)β and IL-6. We generated a TGFβ-transgenic strain, in which TGFβ was selectively expressed under the control of the IL-2 promoter, and crossed it to the 2D2 strain. TGFβ-Tg x 2D2 mice developed more severe EAE than 2D2 mice, and ex vivo-isolated TGFβ-Tg x 2D2 T cells produced massive amounts of IL-17 [75].

These findings, which were published alongside others [76, 77], brought together the concept that IL-23 is not the differentiating factor for Th17 cells. Rather, a combination of cytokines (TGFβ + IL-6) mediates the initial differentiation of Th17 cells. Further studies showed that Th17 differentiation is a multi-step process. Upon the induction of Th17 differentiation by TGFβ and IL-6, the response is amplified by IL-21 [78, 79] and the phenotype is stabilized by IL-23 [80]. Th17 cells have been implicated in the pathogenesis of human autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis [81], arthritis [82], type I diabetes [83], and notably, MS [84] (the role of Th17 responses in human autoimmune disease is reviewed extensively by Maddur et al. [85]). Anti-Th17 pathway biologics are now being tested in the clinic. Ustekinumab, a human monoclonal antibody that targets IL-12p40 (thus blocking both IL-12- and IL-23-dependent signals), is a well-tolerated therapy for psoriasis that is also being tested for Crohn’s disease [86]. Secukinumab is a human anti-IL17A monoclonal antibody that recently showed promising effects in a phase II clinical trial for psoriasis [87], and phase II clinical trials are in progress to determine whether it can modulate RRMS [88]. Excitingly, data suggest that it can reduce the frequency of gadolinium-enhancing lesions seen on MRI scans of RRMS brains (AIN457 MS Study group, presented at ECTRIMS 2012). Thus, the discovery of the Th17 paradigm of autoimmune inflammation, which was largely driven by work using the EAE model, has led to the development of promising therapeutics for human autoimmune disease.

Our lab has continued to use MOG35-55-driven EAE to dissect the signals and players that contribute to Th17-driven autoimmune responses. We established a crucial role for IL-6 in promoting Th17 responses at the expense of regulatory T cell (Treg) expansion. IL-6 synergizes with TGFβ to drive IL-17 production [75], and IL-6−/− mice develop mild EAE upon immunization, relative to WT controls. However, in vivo depletion of Treg restored both disease severity and in vivo Th17 generation, indicating that IL-6 may control the balance between TGFβ-mediated Th17/Treg differentiation [79] (Figure 2B). To understand the molecular basis for the development of Th17 cells, we undertook a temporal transcriptional analysis of developing Th17 cells at 18 different time points and generated a regulatory network that governs the development of Th17 cells. In the process, we identified major nodes and subnodes that govern Th17 generation [89].

We identified serum glucorticoid kinase 1 (Sgk1), a major node downstream of IL-23, as being essential for the optimal expression of IL-23 receptor on Th17 cells [89, 90] Mice that lack Sgk1 specifically in CD4+ T cells develop EAE of lessened severity; importantly, so do mice lacking Sgk1 only in IL-17-producing T cells [90]. Sgk1 is a salt-sensing kinase that regulates sodium retention in cells, and is itself upregulated by the presence of salt [91]. Intriguingly, a high-salt diet can make WT mice susceptible to EAE of increased severity and earlier onset [90, 92]; by contrast, high salt food has negligible effect on the disease severity of mice lacking Sgk1 in CD4+ T cells [90]. Furthermore, exposure of human Th17 cells to increased NaCl in culture increases their ability to produce IL-17 [92]. In this series of studies, the EAE model has been used to draw a link between genetic susceptibility, environment, immune function and disease pathology.

Negative signaling receptors in EAE

While T cells proliferate rapidly upon recognizing their cognate antigen in the context of a normal immune response, it is also critical that such responses are rapidly shut down once a pathogen is cleared. T cells can be induced to express a plethora of negative regulatory receptors that act in an autocrine fashion to terminate their responses. This can take place either by initiating a program of cell death or by inducing the production of immunomodulatory cytokines. Dysregulation of negative receptor signaling by T cells is a key mechanism underpinning autoimmune pathologies [93].

The surface molecule cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) is one of the best studied of T cell negative receptors. It is a homolog of the costimulatory molecule CD28, but with a higher affinity for the CD28 ligands B7.1 and B7.2. CTLA-4 is rapidly upregulated on activated T cells, and downregulates T cell activation by out-competing CD28 for access to its ligands [94]. Its role in modulating autoimmunity has been well studied using the EAE model. In vivo blockade of CTLA-4 with a monoclonal antibody worsened the severity of both PLP- [95, 96] and MBP-mediated [97] EAE. Further, anti-CTLA-4 antibody could abrogate the relative resistance of Balb/C strain mice to EAE induction [98].

Programmed death-1 (PD-1) is another extensively studied inhibitory T cell receptor. Ligation of PD-1 results in inhibition of phosphoinositide 3′ kinase (PI3K)-dependent inflammatory and proliferative signals [99]. It was therefore logical to hypothesize that loss of PD-1 signaling in vivo could enhance the development of EAE. Indeed, in vivo blockade of PD-1 [100] or its ligands [101] using a monoclonal antibody resulted in the worsening of EAE severity. Further, PD-1-deficient mice develop more severe EAE than controls upon immunization with MOG35-55 [102]. Interestingly, PD-1−/− T cells displayed enhanced production of inflammatory cytokines, but not increased proliferation, upon restimulation with MOG35-55. These findings highlight the utility of the EAE model in uncovering the mechanistic bases for immune function.

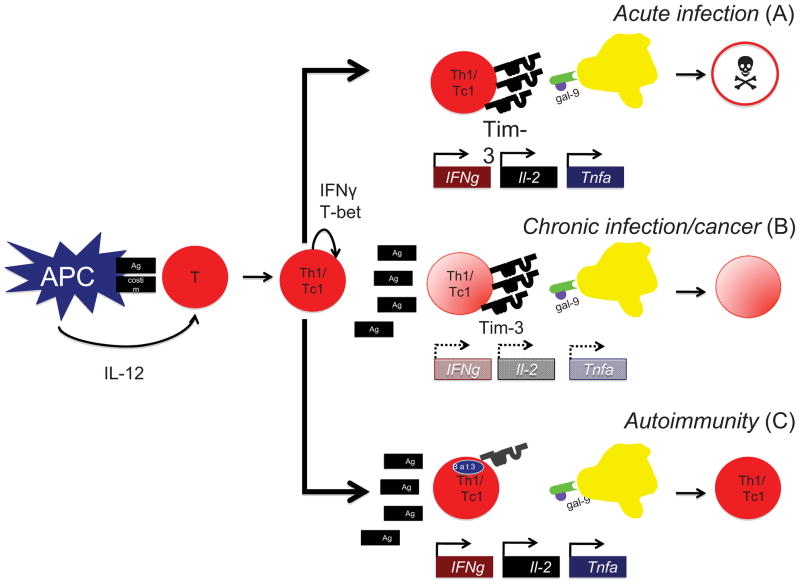

Our group has had a long-standing interest in the function of T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing-3 (Tim-3), a negative regulatory receptor specifically expressed on IFNγ-producing T cells. Tim-3 is highly expressed on CD4+ T cells isolated from the CNS of PLP139-151-immunized animals. Further, in vivo blockade of Tim-3 signaling worsened the severity on ongoing EAE, with macrophage and neutrophil infiltration of the parenchyma accompanied by significant demyelination of spinal cord neurons [103]. Future work demonstrated that Tim-3−/− T cells were refractory to in vivo peripheral tolerance [104, 105]. Galectin-9 was identified as the ligand for Tim-3, and we found that knocking it down in vivo resulted in the exacerbation of MOG35-55-driven EAE [106]. Taken together, these data suggest that absence or in vivo blockade of Tim-3 signaling can worsen the severity of EAE in multiple models of disease. Importantly, Tim-3 expression is downregulated on T cells isolated from the peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients, suggesting that loss of Tim-3 mediated negative regulatory signaling correlates with human autoimmune disease [107]. Curiously, Tim-3 expression is higher in MS patients undergoing immunomodulatory therapy, as compared to patients who are not [108], suggesting that Tim-3 function and regulation are plastic and potentially targetable therapeutically.

While the significance of Tim-3 signaling in disease is clear (Figure 3), the signaling pathways downstream are less well understood. We have recently identified the adaptor molecule HLA-B-associated transcript 3 (Bat3) as a repressor of Tim-3 signaling. Bat3 physically binds to Tim-3, and overexpression of Bat3 protects Th1 cells from Tim-3 mediated cell death. Importantly, mice that lack Bat3 in the immune compartment develop less severe EAE upon active immunization of MOG35-55 than wildtype controls [16]. As Bat3 is not highly expressed in Th17 cells, and as the role of IL-17-driven responses in promoting EAE is well described [55, 75], we sought to develop a means by which to test the consequences of Bat3 expression in myelin-antigen reactive Th1 cells alone. To do so, we exploited retrovirally mediated gene transfer techniques. 2D2 cells were stimulated in vitro under conditions that promoted Th1 differentiation. While in culture, they were transduced by non-replicating retroviral particles that either encoded Bat3 cDNA or a Bat3-targeted shRNA construct. Transduced cells were then transferred to Rag1−/− animals and monitored for signs of disease. Bat3-overexpressing 2D2 Th1 cells induced EAE of greater severity than controls, while Bat3 knockdown (Bat3KD) 2D2 T cells were completely ineffective in their ability to transfer EAE [16]. Intriguingly, approximately half of all Bat3KD 2D2 recipients developed peripheral lymphoid populations that were CD4+Tim-3hiPD-1−IFNγdim. This phenotype is highly reminiscent of that of dysfunctional exhausted T cells recently identified from the peripheral blood of HIV-1-infected individuals [109]. Indeed, the role of Tim-3 in mediating the dysfunction of exhausted T cells in HIV-1 [109], HCV [110] and cancers [111, 112] has been the subject of considerable interest in the last few years. Thus, by modulating the expression in a single molecule in myelin-antigen-reactive T cells, we may be able to shift an immune response from a self-destructive inflammatory one to one that is self-limiting in nature [16]. By manipulating the expression of inhibitory receptors on, and the cytokine balance of, inflammatory T cells, we hope to achieve our long term goal of inducing resolution of autoimmune diseases such as MS (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Role of Tim-3 in normal and pathologic immune responses.

Upon encountering its cognate antigen in the context of an IL-12-rich milieu, a T cell will differentiate into a IFNγ+ Th1 (CD4+) or Tc1 (CD8+) cell. A. In the case of an acute infection in which the antigen is ultimately cleared, Th1/Tc1 cells will secrete large quantities of the proinflammatory cytokines IFNγ, TNFα and IL-2, and upon terminal differentiation, will express high levels of Tim-3 [103]. Upon interaction with the Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 [106], these Tim-3+ T cells will undergo cell death and will be deleted from the repertoire. B. In instances of chronic viral infections [109, 110] and malignancies [111, 112], Tim-3 expression may become decoupled from the production of inflammatory cytokines. In the presence of persistent antigen, exhausted T cells progressively lose the capacity to produce IFNγ, TNFα and IL-2, and begin to express Tim-3. These exhausted T cells may persist in the periphery but ultimately undergo cell death [113]. C. In the case of autoimmunity, autoreactive Th1 cells produce great quantities of inflammatory cytokines and mediate tissue destruction. In the case of MS, these cells express display defective Tim-3 signaling [107, 108]. One possible mechanism for T cell dysfunction may be increased expression of Bat3, which represses Tim-3 signaling. Strategies that modulate the expression and function of Bat3 may result in augmentation of Tim-3 responses and subsequent amelioration of autoimmunity [16].

Concluding remarks

Dr. Abul Abbas, to whom this volume is dedicated, has worked for the last three decades in the field of autoimmunity and tolerance. He has made seminal contributions to our understanding of cytokine balance (Th1/Th2 paradigm), costimulatory molecules (CD28/CTLA-4) and regulatory T cell function (Foxp3+). He has also helped generate multiple transgenic models of autoimmunity using model antigens. Abul has an incredible talent for synthesizing complex information in a succinct and simple manner, and with his lectures he has engaged audiences all over the world. Blessed with a gregarious personality and infectious laugh, it is not a rarity to spot him at a conference, in the center of a large group of his many friends and colleagues. Finally, an editorial note that this dedicated issue to Abul Abbas is part of the Journal of Autoimmunity’s focus each year on recognition of outstanding autoimmunologists and particularly contributors to the International Congress of Autoimmunity. Abul has graciously taught an introductory immunology course to a group of international students for many years at this congress. Our previous honorees have included Ian Mackay, Noel Rose, Harry Moutsopoulos, Pierre Youinou, and Chella David [114–116]. Above all, Abul has been a friend, supporter, source of counsel and mentor to many of us in the immunology community. We are immensely grateful to have him.

Highlights.

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is a well established mouse model of MS.

Different models of EAE recapitulate different aspects of MS pathology

EAE may be induced via active peptide immunization or via transfer of CNS-reactive T cells.

EAE has yielded critical insights into our understanding of T cell differentiation.

EAE has also increased our knowledge of the function of negative regulatory T cell receptors.

Footnotes

Declarations

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Manu Rangachari, Email: manu.rangachari@crchuq.ulaval.ca.

Vijay K. Kuchroo, Email: vkuchroo@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Frohman EM, Racke MK, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis--the plaque and its pathogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:942–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meuth SG, Gobel K, Wiendl H. Immune therapy of multiple sclerosis--future strategies. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:4489–97. doi: 10.2174/138161212802502198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper GS, Bynum ML, Somers EC. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J Autoimmun. 2009;33:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards TL, Alvord EC, Jr, He Y, Petersen K, Peterson J, Cosgrove S, Heide AC, Marro K, Rose LM. Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in non-human primates: diffusion imaging of acute and chronic brain lesions. Mult Scler. 1995;1:109–17. doi: 10.1177/135245859500100209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aritake K, Koh CS, Inoue A, Yabuuchi F, Kitagaki K, Ikoma Y, Hayashi S. Effects of human recombinant-interferon beta in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in guinea pigs. Pharm Biol. 2010;48:1273–9. doi: 10.3109/13880201003770135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearce JM. Historical descriptions of multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2005;54:49–53. doi: 10.1159/000087387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonald WI. The dynamics of multiple sclerosis. The Charcot Lecture. J Neurol. 1993;240:28–36. doi: 10.1007/BF00838443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald I. Multiple sclerosis in its European matrix. Mult Scler. 2002;8:181–91. doi: 10.1191/1352458502ms821oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wingerchuk DM, Lucchinetti CF, Noseworthy JH. Multiple sclerosis: current pathophysiological concepts. Lab Invest. 2001;81:263–81. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, Goodkin D, Hartung HP, Lublin FD, McFarland HF, Paty DW, Polman CH, Reingold SC, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:121–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antel J, Antel S, Caramanos Z, Arnold DL, Kuhlmann T. Primary progressive multiple sclerosis: part of the MS disease spectrum or separate disease entity? Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:627–38. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0953-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuohy VK, Lu Z, Sobel RA, Laursen RA, Lees MB. Identification of an encephalitogenic determinant of myelin proteolipid protein for SJL mice. J Immunol. 1989;142:1523–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tompkins SM, Padilla J, Dal Canto MC, Ting JP, Van Kaer L, Miller SD. De novo central nervous system processing of myelin antigen is required for the initiation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2002;168:4173–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batoulis H, Recks MS, Addicks K, Kuerten S. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis--achievements and prospective advances. APMIS. 2011;119:819–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McRae BL, Kennedy MK, Tan LJ, Dal Canto MC, Picha KS, Miller SD. Induction of active and adoptive relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) using an encephalitogenic epitope of proteolipid protein. J Neuroimmunol. 1992;38:229–40. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90016-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rangachari M, Zhu C, Sakuishi K, Xiao S, Karman J, Chen A, Angin M, Wakeham A, Greenfield EA, Sobel RA, et al. Bat3 promotes T cell responses and autoimmunity by repressing Tim-3-mediated cell death and exhaustion. Nat Med. 2012;18:1394–400. doi: 10.1038/nm.2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berard JL, Wolak K, Fournier S, David S. Characterization of relapsing-remitting and chronic forms of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in C57BL/6 mice. Glia. 2010;58:434–45. doi: 10.1002/glia.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Domingues HS, Mues M, Lassmann H, Wekerle H, Krishnamoorthy G. Functional and pathogenic differences of Th1 and Th17 cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zamvil S, Nelson P, Trotter J, Mitchell D, Knobler R, Fritz R, Steinman L. T-cell clones specific for myelin basic protein induce chronic relapsing paralysis and demyelination. Nature. 1985;317:355–8. doi: 10.1038/317355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zamvil SS, Mitchell DJ, Moore AC, Kitamura K, Steinman L, Rothbard JB. T-cell epitope of the autoantigen myelin basic protein that induces encephalomyelitis. Nature. 1986;324:258–60. doi: 10.1038/324258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy MK, Clatch RJ, Dal Canto MC, Trotter JL, Miller SD. Monoclonal antibody-induced inhibition of relapsing EAE in SJL/J mice correlates with inhibition of neuroantigen-specific cell-mediated immune responses. J Neuroimmunol. 1987;16:345–64. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(87)90110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitham RH, Wingett D, Wineman J, Mass M, Wegmann K, Vandenbark A, Offner H. Treatment of relapsing autoimmune encephalomyelitis with T cell receptor V beta-specific antibodies when proteolipid protein is the autoantigen. J Neurosci Res. 1996;45:104–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960715)45:2<104::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy MK, Tan LJ, Dal Canto MC, Tuohy VK, Lu ZJ, Trotter JL, Miller SD. Inhibition of murine relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by immune tolerance to proteolipid protein and its encephalitogenic peptides. J Immunol. 1990;144:909–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McRae BL, Vanderlugt CL, Dal Canto MC, Miller SD. Functional evidence for epitope spreading in the relapsing pathology of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 1995;182:75–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitham RH, Bourdette DN, Hashim GA, Herndon RM, Ilg RC, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Lymphocytes from SJL/J mice immunized with spinal cord respond selectively to a peptide of proteolipid protein and transfer relapsing demyelinating experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1991;146:101–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMahon EJ, Bailey SL, Castenada CV, Waldner H, Miller SD. Epitope spreading initiates in the CNS in two mouse models of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2005;11:335–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quintana FJ, Farez MF, Izquierdo G, Lucas M, Cohen IR, Weiner HL. Antigen microarrays identify CNS-produced autoantibodies in RRMS. Neurology. 2012;78:532–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318247f9f3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyagawa F, Gutermuth J, Zhang H, Katz SI. The use of mouse models to better understand mechanisms of autoimmunity and tolerance. J Autoimmun. 2010;35:192–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adlard K, Tsaknardis L, Beam A, Bebo BF, Jr, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Immunoregulation of encephalitogenic MBP-NAc1-11-reactive T cells by CD4+ TCR-specific T cells involves IL-4, IL-10 and IFN-gamma. Autoimmunity. 1999;31:237–48. doi: 10.3109/08916939908994069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waldner H, Whitters MJ, Sobel RA, Collins M, Kuchroo VK. Fulminant spontaneous autoimmunity of the central nervous system in mice transgenic for the myelin proteolipid protein-specific T cell receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3412–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollinger B, Krishnamoorthy G, Berer K, Lassmann H, Bosl MR, Dunn R, Domingues HS, Holz A, Kurschus FC, Wekerle H. Spontaneous relapsing-remitting EAE in the SJL/J mouse: MOG-reactive transgenic T cells recruit endogenous MOG-specific B cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1303–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seong E, Saunders TL, Stewart CL, Burmeister M. To knockout in 129 or in C57BL/6: that is the question. Trends Genet. 2004;20:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendel I, Kerlero de Rosbo N, Ben-Nun A. A myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide induces typical chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in H-2b mice: fine specificity and T cell receptor V beta expression of encephalitogenic T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1951–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suen WE, Bergman CM, Hjelmstrom P, Ruddle NH. A critical role for lymphotoxin in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1233–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korner H, Riminton DS, Strickland DH, Lemckert FA, Pollard JD, Sedgwick JD. Critical points of tumor necrosis factor action in central nervous system autoimmune inflammation defined by gene targeting. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1585–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran EH, Prince EN, Owens T. IFN-gamma shapes immune invasion of the central nervous system via regulation of chemokines. J Immunol. 2000;164:2759–68. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malipiero U, Frei K, Spanaus KS, Agresti C, Lassmann H, Hahne M, Tschopp J, Eugster HP, Fontana A. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis is chronic/relapsing in perforin knockout mice, but monophasic in Fas- and Fas ligand-deficient lpr and gld mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3151–60. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eugster HP, Frei K, Bachmann R, Bluethmann H, Lassmann H, Fontana A. Severity of symptoms and demyelination in MOG-induced EAE depends on TNFR1. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:626–32. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199902)29:02<626::AID-IMMU626>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du C, Sriram S. Increased severity of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in lyn−/− mice in the absence of elevated proinflammatory cytokine response in the central nervous system. J Immunol. 2002;168:3105–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bettelli E, Sullivan B, Szabo SJ, Sobel RA, Glimcher LH, Kuchroo VK. Loss of T-bet, but not STAT1, prevents the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:79–87. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hjelmstrom P, Juedes AE, Fjell J, Ruddle NH. B-cell-deficient mice develop experimental allergic encephalomyelitis with demyelination after myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein sensitization. J Immunol. 1998;161:4480–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bullard DC, Hu X, Adams JE, Schoeb TR, Barnum SR. p150/95 (CD11c/CD18) expression is required for the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:2001–8. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koh DR, Fung-Leung WP, Ho A, Gray D, Acha-Orbea H, Mak TW. Less mortality but more relapses in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in CD8−/− mice. Science. 1992;256:1210–3. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spahn TW, Issazadah S, Salvin AJ, Weiner HL. Decreased severity of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide 33 – 35-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice with a disrupted TCR delta chain gene. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:4060–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199912)29:12<4060::AID-IMMU4060>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friese MA, Fugger L. Pathogenic CD8(+) T cells in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:132–41. doi: 10.1002/ana.21744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crawford MP, Yan SX, Ortega SB, Mehta RS, Hewitt RE, Price DA, Stastny P, Douek DC, Koup RA, Racke MK, et al. High prevalence of autoreactive, neuroantigen-specific CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis revealed by novel flow cytometric assay. Blood. 2004;103:4222–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ford ML, Evavold BD. Specificity, magnitude, and kinetics of MOG-specific CD8+ T cell responses during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:76–85. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blanchard N, Shastri N. Coping with loss of perfection in the MHC class I peptide repertoire. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bettelli E, Pagany M, Weiner HL, Linington C, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific T cell receptor transgenic mice develop spontaneous autoimmune optic neuritis. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1073–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pau D, Al Zubidi N, Yalamanchili S, Plant GT, Lee AG. Optic neuritis. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:833–42. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Litzenburger T, Fassler R, Bauer J, Lassmann H, Linington C, Wekerle H, Iglesias A. B lymphocytes producing demyelinating autoantibodies: development and function in gene-targeted transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 1998;188:169–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krishnamoorthy G, Lassmann H, Wekerle H, Holz A. Spontaneous opticospinal encephalomyelitis in a double-transgenic mouse model of autoimmune T cell/B cell cooperation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2385–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI28330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bettelli E, Baeten D, Jager A, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific T and B cells cooperate to induce a Devic-like disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2393–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI28334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Misu T, Fujihara K, Nakashima I, Miyazawa I, Okita N, Takase S, Itoyama Y. Pure optic-spinal form of multiple sclerosis in Japan. Brain. 2002;125:2460–8. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jager A, Dardalhon V, Sobel RA, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. Th1, Th17, and Th9 effector cells induce experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with different pathological phenotypes. J Immunol. 2009;183:7169–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Encinas JA, Wicker LS, Peterson LB, Mukasa A, Teuscher C, Sobel R, Weiner HL, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Kuchroo VK. QTL influencing autoimmune diabetes and encephalomyelitis map to a 0.15-cM region containing Il2. Nat Genet. 1999;21:158–60. doi: 10.1038/5941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Degenhardt A, Ramagopalan SV, Scalfari A, Ebers GC. Clinical prognostic factors in multiple sclerosis: a natural history review. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:672–82. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson AC, Chandwaskar R, Lee DH, Sullivan JM, Solomon A, Rodriguez-Manzanet R, Greve B, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK. A transgenic model of central nervous system autoimmunity mediated by CD4+ and CD8+ T and B cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:2084–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136:2348–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cherwinski HM, Schumacher JH, Brown KD, Mosmann TR. Two types of mouse helper T cell clone. III. Further differences in lymphokine synthesis between Th1 and Th2 clones revealed by RNA hybridization, functionally monospecific bioassays, and monoclonal antibodies. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1229–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.5.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Waal Malefyt R, Figdor CG, Huijbens R, Mohan-Peterson S, Bennett B, Culpepper J, Dang W, Zurawski G, de Vries JE. Effects of IL-13 on phenotype, cytokine production, and cytotoxic function of human monocytes. Comparison with IL-4 and modulation by IFN-gamma or IL-10. J Immunol. 1993;151:6370–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lucey DR. Evolution of the type-1 (Th1)-type-2 (Th2) cytokine paradigm. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1999;13:1–9. v. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adorini L, Guery JC, Trembleau S. Manipulation of the Th1/Th2 cell balance: an approach to treat human autoimmune diseases? Autoimmunity. 1996;23:53–68. doi: 10.3109/08916939608995329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferber IA, Brocke S, Taylor-Edwards C, Ridgway W, Dinisco C, Steinman L, Dalton D, Fathman CG. Mice with a disrupted IFN-gamma gene are susceptible to the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) J Immunol. 1996;156:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krakowski M, Owens T. Interferon-gamma confers resistance to experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1641–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chu CQ, Wittmer S, Dalton DK. Failure to suppress the expansion of the activated CD4 T cell population in interferon gamma-deficient mice leads to exacerbation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2000;192:123–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Becher B, Durell BG, Noelle RJ. Experimental autoimmune encephalitis and inflammation in the absence of interleukin-12. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:493–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI15751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oppmann B, Lesley R, Blom B, Timans JC, Xu Y, Hunte B, Vega F, Yu N, Wang J, Singh K, et al. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity. 2000;13:715–25. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gran B, Zhang GX, Yu S, Li J, Chen XH, Ventura ES, Kamoun M, Rostami A. IL-12p35-deficient mice are susceptible to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: evidence for redundancy in the IL-12 system in the induction of central nervous system autoimmune demyelination. J Immunol. 2002;169:7104–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.7104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cua DJ, Sherlock J, Chen Y, Murphy CA, Joyce B, Seymour B, Lucian L, To W, Kwan S, Churakova T, et al. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 2003;421:744–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang GX, Gran B, Yu S, Li J, Siglienti I, Chen X, Kamoun M, Rostami A. Induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in IL-12 receptor-beta 2-deficient mice: IL-12 responsiveness is not required in the pathogenesis of inflammatory demyelination in the central nervous system. J Immunol. 2003;170:2153–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, Chang SH, Nurieva R, Wang YH, Wang Y, Hood L, Zhu Z, Tian Q, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–41. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, Mattson J, Basham B, Sedgwick JD, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Parham C, Chirica M, Timans J, Vaisberg E, Travis M, Cheung J, Pflanz S, Zhang R, Singh KP, Vega F, et al. A receptor for the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23 is composed of IL-12Rbeta1 and a novel cytokine receptor subunit, IL-23R. J Immunol. 2002;168:5699–708. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O’Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Wahl SM, Schoeb TR, Weaver CT. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Flavell RA, Stockinger B. Signals mediated by transforming growth factor-beta initiate autoimmune encephalomyelitis, but chronic inflammation is needed to sustain disease. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1151–6. doi: 10.1038/ni1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nurieva R, Yang XO, Martinez G, Zhang Y, Panopoulos AD, Ma L, Schluns K, Tian Q, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, et al. Essential autocrine regulation by IL-21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature. 2007;448:480–3. doi: 10.1038/nature05969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Korn T, Bettelli E, Gao W, Awasthi A, Jager A, Strom TB, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2007;448:484–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bettelli E, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Th17: the third member of the effector T cell trilogy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:652–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fitch E, Harper E, Skorcheva I, Kurtz SE, Blauvelt A. Pathophysiology of psoriasis: recent advances on IL-23 and Th17 cytokines. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9:461–7. doi: 10.1007/s11926-007-0075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scheinecker C, Smolen JS. Rheumatoid arthritis in 2010: from the gut to the joint. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:73–5. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shao S, He F, Yang Y, Yuan G, Zhang M, Yu X. Th17 cells in type 1 diabetes. Cell Immunol. 2012;280:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fletcher JM, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Tubridy N, Mills KH. T cells in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;162:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maddur MS, Miossec P, Kaveri SV, Bayry J. Th17 cells: biology, pathogenesis of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, and therapeutic strategies. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yeilding N, Szapary P, Brodmerkel C, Benson J, Plotnick M, Zhou H, Goyal K, Schenkel B, Giles-Komar J, Mascelli MA, et al. Development of the IL-12/23 antagonist ustekinumab in psoriasis: past, present, and future perspectives--an update. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1263:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rich P, Sigurgeirsson B, Thaci D, Ortonne JP, Paul C, Schopf RE, Morita A, Roseau K, Harfst E, Guettner A, et al. Secukinumab induction and maintenance therapy in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II regimen-finding study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:402–11. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miossec P, Kolls JK. Targeting IL-17 and TH17 cells in chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:763–76. doi: 10.1038/nrd3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yosef N, Shalek AK, Gaublomme JT, Jin H, Lee Y, Awasthi A, Wu C, Karwacz K, Xiao S, Jorgolli M, et al. Dynamic regulatory network controlling TH17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2013;496:461–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu C, Yosef N, Thalhamer T, Zhu C, Xiao S, Kishi Y, Regev A, Kuchroo VK. Induction of pathogenic T17 cells by inducible salt-sensing kinase SGK1. Nature. 2013;496:513–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lang F, Bohmer C, Palmada M, Seebohm G, Strutz-Seebohm N, Vallon V. (Patho)physiological significance of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoforms. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1151–78. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00050.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kleinewietfeld M, Manzel A, Titze J, Kvakan H, Yosef N, Linker RA, Muller DN, Hafler DA. Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic T17 cells. Nature. 2013;496:518–22. doi: 10.1038/nature11868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pentcheva-Hoang T, Corse E, Allison JP. Negative regulators of T-cell activation: potential targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer, autoimmune disease, and persistent infections. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:67–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McCoy KD, Le Gros G. The role of CTLA-4 in the regulation of T cell immune responses. Immunol Cell Biol. 1999;77:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1999.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Karandikar NJ, Vanderlugt CL, Walunas TL, Miller SD, Bluestone JA. CTLA-4: a negative regulator of autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1996;184:783–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hurwitz AA, Sullivan TJ, Krummel MF, Sobel RA, Allison JP. Specific blockade of CTLA-4/B7 interactions results in exacerbated clinical and histologic disease in an actively-induced model of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;73:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Perrin PJ, Maldonado JH, Davis TA, June CH, Racke MK. CTLA-4 blockade enhances clinical disease and cytokine production during experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1996;157:1333–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hurwitz AA, Sullivan TJ, Sobel RA, Allison JP. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) limits the expansion of encephalitogenic T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)-resistant BALB/c mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3013–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042684699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Francisco LM, Sage PT, Sharpe AH. The PD-1 pathway in tolerance and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:219–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Salama AD, Chitnis T, Imitola J, Ansari MJ, Akiba H, Tushima F, Azuma M, Yagita H, Sayegh MH, Khoury SJ. Critical role of the programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway in regulation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2003;198:71–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhu B, Guleria I, Khosroshahi A, Chitnis T, Imitola J, Azuma M, Yagita H, Sayegh MH, Khoury SJ. Differential role of programmed death-ligand 1 and programmed death-ligand 2 in regulating the susceptibility and chronic progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;176:3480–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Carter LL, Leach MW, Azoitei ML, Cui J, Pelker JW, Jussif J, Benoit S, Ireland G, Luxenberg D, Askew GR, et al. PD-1/PD-L1, but not PD-1/PD-L2, interactions regulate the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;182:124–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Monney L, Sabatos CA, Gaglia JL, Ryu A, Waldner H, Chernova T, Manning S, Greenfield EA, Coyle AJ, Sobel RA, et al. Th1-specific cell surface protein Tim-3 regulates macrophage activation and severity of an autoimmune disease. Nature. 2002;415:536–41. doi: 10.1038/415536a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sabatos CA, Chakravarti S, Cha E, Schubart A, Sanchez-Fueyo A, Zheng XX, Coyle AJ, Strom TB, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK. Interaction of Tim-3 and Tim-3 ligand regulates T helper type 1 responses and induction of peripheral tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1102–10. doi: 10.1038/ni988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sanchez-Fueyo A, Tian J, Picarella D, Domenig C, Zheng XX, Sabatos CA, Manlongat N, Bender O, Kamradt T, Kuchroo VK, et al. Tim-3 inhibits T helper type 1-mediated auto- and alloimmune responses and promotes immunological tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1093–101. doi: 10.1038/ni987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhu C, Anderson AC, Schubart A, Xiong H, Imitola J, Khoury SJ, Zheng XX, Strom TB, Kuchroo VK. The Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 negatively regulates T helper type 1 immunity. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1245–52. doi: 10.1038/ni1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Koguchi K, Anderson DE, Yang L, O’Connor KC, Kuchroo VK, Hafler DA. Dysregulated T cell expression of TIM3 in multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1413–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang L, Anderson DE, Kuchroo J, Hafler DA. Lack of TIM-3 immunoregulation in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2008;180:4409–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jones RB, Ndhlovu LC, Barbour JD, Sheth PM, Jha AR, Long BR, Wong JC, Satkunarajah M, Schweneker M, Chapman JM, et al. Tim-3 expression defines a novel population of dysfunctional T cells with highly elevated frequencies in progressive HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2763–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Golden-Mason L, Palmer BE, Kassam N, Townshend-Bulson L, Livingston S, McMahon BJ, Castelblanco N, Kuchroo V, Gretch DR, Rosen HR. Negative immune regulator Tim-3 is overexpressed on T cells in hepatitis C virus infection and its blockade rescues dysfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Virol. 2009;83:9122–30. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00639-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sakuishi K, Apetoh L, Sullivan JM, Blazar BR, Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2187–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhou Q, Munger ME, Veenstra RG, Weigel BJ, Hirashima M, Munn DH, Murphy WJ, Azuma M, Anderson AC, Kuchroo VK, et al. Co-expression of Tim-3 and PD-1 identifies a CD8+ T-cell exhaustion phenotype in mice with disseminated acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2011 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-310425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:492–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gershwin ME, Shoenfeld Y. Chella David: a lifetime contribution in translational immunology. J Autoimmun. 2011;37:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jamin C, Renaudineau Y, Pers JO. Pierre Youinou: when intuition and determination meet autoimmunity. J Autoimun. 2012;39:117–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tzioufas AG, Kapsogeorgou EK, Moutsopoulos HM. Pathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome: what we know and what we should learn. J Autoimmun. 2012;39:4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]