Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the influence of targeted trypsin digestion and 16 hours compression loading on MR parameters and the mechanical and biochemical properties of bovine disc segments.

Materials and Methods

Twenty-two 3-disc bovine coccygeal segments underwent compression loading for 16 hours after the nucleus pulposus (NP) of each disc was injected with a solution of trypsin or buffer. The properties of the NP and annulus fibrosus (AF) tissues of each disc were analyzed by quantitative MRI, biochemical tests, and confined compression tests.

Results

Loading had a significant effect on the MR properties (T1, T2, T1ρ, MTR, ADC) of both the NP and AF tissues. Loading had a greater effect on the MR parameters and biochemical composition of the NP than trypsin. In contrast, trypsin had a larger effect on the mechanical properties. Our data also indicated that localized trypsin injection predominantly affected the NP. T1ρ was sensitive to loading and correlated with the water content of the NP and AF but not with their proteoglycan content.

Conclusion

Our studies indicate that physiological loading is an important parameter to consider and that T1ρ contributes new information in efforts to develop quantitative MRI as a noninvasive diagnostic tool to detect changes in early disc degeneration.

Keywords: quantitative MRI, intervertebral disc, T1ρ, biomechanics, loading

Despite a relentless search for adequate and effective treatment, low back pain is one of the most prevalent (affecting up to 70% of people once during their lifetime) (1) and costly illness in today’s society (up to 50 billion dollars per year in the U.S.—not including earning and productivity losses) (2). It has long been recognized that the integrity of the intervertebral disc (IVD), part of a three-joint complex that determines the motion segment of the spine, is an essential component of normal spinal function. Alterations in the disc’s structure may cause back pain and referred pain with or without neurological impairment (3), in addition to significantly compromising the biomechanical integrity of the motion segment (4). While disc degeneration has been implicated as a major etiologic component of low back pain (5,6), there has been relatively little study in developing an objective, accurate, noninvasive diagnostic tool in the detection and quantification of matrix changes in early disc degeneration. Hence, the development of quantitative MR technology could allow early diagnostic and subsequent treatment of disc degeneration and thus reduce incidences of low back pain.

IVDs are not uniform in composition, but consist of two distinct regions: The annulus fibrosus (AF) is a fibrocartilage and contains concentric lamellae rich in collagen, whereas the nucleus pulposus (NP) is a less structured gelatinous substance rich in proteoglycans (7). The disc is thought to resist compressive forces by a swelling pressure that exerts tensile forces on the fibrous collagen network (8). When a weakness in the collagenous network of the AF occurs, the swelling pressure within the NP may result in disc protrusion (9). With age, the swelling pressure of the NP decreases because of progressive degenerative changes that may begin as early as the third decade of life (10). These changes appear to be related to a loss of disc proteoglycans and/or to collagen network damage (10,11). The biomechanical function of the spine is reflected by its structural architecture, and therefore depends critically on the organization and composition of disc matrix components. Events that decrease glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content in the NP will impair its functional ability. Such a decrease occurs relatively early during adult human life and may be a prelude to tissue degeneration.

Surgical treatments of degenerative disc disorders that are currently considered the “gold standard” include discectomy and spinal fusion. Although these surgical procedures produce a relatively good short-term clinical result in relieving pain, they alter the biomechanics of the spine, leading to further degeneration of the surrounding tissue and the discs at adjacent levels (12–14). The future of disc pathology treatment lies in the ability to treat the underlying cause at the level of the disc matrix rather than attempting to empirically treat the symptoms. However, little work has been done to systematically and objectively study quantitative MR technology as a method to investigate the pathologic and treatment-induced processes that occur in the IVD.

Previous studies have evaluated the potential of quantitative MRI as a diagnostic tool of disc degeneration by attempting to correlate the MRI signal to disc tissue degeneration (15–20). T1 and T2 have been shown to decrease significantly in the NP with Thompson grade 4 degeneration, while the magnetization transfer (MT) increased (17). The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) has also been shown to decrease in the NP in a direction-dependent manner with disc degeneration (18,19). Correlation studies between MR parameters T1, T2, MT, and ADC have demonstrated that quantitative MRI reflects not only the NP matrix composition of the disc, but also the structural integrity of the NP matrix (17,18). Recently, the spin-lattice relaxation in the rotating frame, T1ρ, which detects low-frequency physicochemical interactions between water and extracellular matrix molecules, has been shown to decrease with disc degeneration and to correlate with the NP proteoglycan content (20).

Studies using targeted enzyme digestion of the NP have allowed the determination of key correlations between MR parameters and the biochemical and mechanical properties of the NP tissue (21,22). Previous studies have shown that targeted collagen degradation of the NP in closed, static, and unloaded disc segments decreased T1, T2, and MT ration (MTR), and affected the ADC in a direction-dependent manner when compared with buffer-injected NPs (22). However, targeting the proteoglycan and/or hyaluronan integrity of the NP by trypsin and hyaluronidase treatment, respectively, while maintaining the matrix content constant did not significantly affect the MR parameters (22). Hence, enzymatic degradation of the NP tissue in a closed and static system influenced MR parameters in an enzyme-specific manner. Another study showed that T1, T2, and ADC correlated with the hydraulic permeability of the NP, measured by confined compression tests, while only diffusion correlated with the compressive modulus of the NP tissue (21). Thus, it was of interest to treat the NP tissue with trypsin under physiological compressive loading and determine its effect on the quantitative MRI, biochemical, and mechanical properties under physiological conditions.

A recent study of compression loading in the physiological range for a period of only 2 hours demonstrated that MR parameters are sensitive to changes in the NP water content induced during loading (21). However, providing a more substantial mechanical challenge to the IVD tissue should better simulate physiological loading over a 16-hour day (23) and thus evaluate if compression enhances loss of proteins in the trypsin-digested disc tissue. Indeed, it was hypothesized that the compression loading conditions employed in this study would result in compositional and structural changes in both the NP and AF tissues that would be detectable with quantitative MRI, but that the enzymatic treatment would affect only the properties of the targeted NP tissue and not of its adjacent AF tissue. It was thus the purpose of the present work to establish the correlations between MR parameters and the biochemical and mechanical properties of the NP undergoing targeted trypsin digestion and axial compression at forces corresponding to 1 MPa loaded at 1 Hz for 16 hours in saline solution. The second aim of this work was to correlate changes in AF tissue due to mechanical loading to MR parameters and to determine if targeted enzymatic digestion of the NP affected the biochemical, mechanical, and MR properties of the adjacent AF tissue. Since T1ρ has recently been correlated to disc degeneration (20), the third goal was to evaluate the sensitivity of T1ρ not only to IVD composition but also to its structural integrity by evaluating its relationship with mechanical loading and biochemical composition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of Tissue

Twenty-two fresh (2–3 years old) bovine tails were obtained from les Abattoirs Billette (St-Louis-de-Gonzague, Quebec, Canada) and transported to the laboratory within 1 to 2 hours of slaughter.

Harvest of Intervertebral Disc Tissues

Fat tissue and some muscle were removed from the upper tail without trimming the tail to the bone. Only enough tissue was removed from the tail to fit in the MRI set-up. Subsequently, segments of three discs were generated by transverse sawing through the middle of the vertebral bodies above the first disc and below the third disc.

Experimental Groups

Sixty-six bovine caudal discs as 3-disc segments were subjected to one of two injections and each of the 3-disc segments underwent one of two loading conditions for a total of four experimental groups. The trypsin group consisted of discs which received an injection into the NP of 5 mg of trypsin from bovine pancreas (T8003; Sigma-Aldrich, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) in 40 µL of a 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.1. Trypsin, a mammalian serine protease, catalyzes the hydrolysis of peptide bonds at the carboxyl side of lysyl and arginyl residues (24). This enzyme thus principally cleaves the proteoglycan core protein. The buffer group included discs where the NP was injected with 40 µL of the Tris buffer.

Three-disc segments were either unloaded or loaded to evaluate the effect of compression loading and the interactive effects of trypsin treatment and mechanical loading. Each segment was placed in plastic bags containing saline solution (0.9% [w/v] NaCl) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 2.5 µg/mL amphotericin B and were kept at 37°C throughout the experiment. The loaded group consisted of segments where both ends were first potted in PMMA before placing in the saline solution and underwent cyclic compression (50N-300N-50N at 1 Hz) for 16 hours. The unloaded group were left in saline for 16 hours. All segments were then paraffin-embedded for MRI.

Quantitative MR Analysis

Paraffin, an MR silent material (25), is used to prevent water loss and to avoid any air surface artifact during MR quantification. The 3-disc segments were placed in a sagittal orientation with the phase encode in an anteroposterior direction to account for the effect of the collagen fibril orientation on MR determinations (26). Two standard solutions of 0.1 mM and 0.2 mM MnCl2 and solutions of 2% by weight agarose with 2% porcine gelatin and 4% by weight of agarose with 2% porcine gelatin were placed centrally, as previously shown (21,22). Vials of the same MnCl2 solutions were placed peripherally to determine the intraassay and interassay variations of the MR technique.

The MR examinations were carried out in a 1.5T whole-body Siemens Avanto System (Erlangen, Germany) using the standard circularly polarized head coil to maximize the signal intensity (17). T1, T2, and MT images were obtained as described previously (21,22), with a field-of-view (FOV) of 200 × 100 mm, a slice thickness of 5 mm, an acquisition image of 256 × 256 pixel, and an acquisition time of 14.75 minutes, 4.3 minutes, and 2.07 minutes, respectively. Briefly, T1 and T2 were determined using the standard Siemens quantification packages based on multiple inversion recovery images for T1 (repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 2100/11 msec, 16 inversion time (TI) from 25 to 1900 msec) and multiple echo trains for T2 (TR = 2000ms, 16 TE every 15 msec). MTR data were obtained using a gradient echo sequence (TR/TE = 300/10 msec) with dual acquisition (pulse off/pulse on at 1.5 kHz away from the central water frequency) using the standard Siemens’ MT pulse. Diffusion images were determined along the anterior/posterior axis using a segmented stimulated echo sequence (acquisition matrix of 128 × 128 pixel, TE/TR = 70/2000 msec, three b-value coefficients of 0, 300, and 600 s/mm2, and acquisition time of 3.33 minutes). The ADC values were determined in all three orthogonal directions, with the slice select ADC in the lateral axis (ADCx), the phase encode ADC in the posteroanterior axis (ADCy), and the readout ADC in cranio-caudal axis (ADCz). Since the resolution was not optimal, diffusion was measured only for the central NP, and not the AF. The T1ρ technique was applied as previously described (20). Briefly, a series of 2D single-slice T1ρ-weighted images were acquired using a self-compensating turbo-spin-echo sequence with the following parameters: FOV of 200 × 100 mm; slice thickness of 5 mm; acquisition matrix of 256 × 256 pixel; TE/TR of 3000/12 msec. The spin-lock pulse durations (TSL) were varied from 10 to 80 msec (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 80 msec). The spin-lock pulse amplitude (BSL) was set to 500 Hz. The total acquisition time was 11.6 minutes.

The analysis for quantitative MRI was performed using a commercial program (MEDx, Medical Numerics, Sterling, VA) allowing detection of the regions of interest and the calculation of average signal intensities (SI) and standard deviations from all the images. The regions of interest for the NP were selected as small polygonal shapes aligned within the center of the NP, with no contact with the AF or the endplate tissues. Once the regions of interest were drawn for each NP in a segment, they were reproduced identically on all T1, T2, MTR, T1ρ, and diffusion images. The same steps were retraced to draw the regions of interest for the AF, in this case analysis of both the anterior and posterior AF was performed. T1, T2, MTR, and ADCs were calculated as described before (21,22), while T1ρ was calculated as described previously (20).

The average intraassay variation of the MR techniques determined from the standard solutions of 0.1 mM and 0.2 mM MnCl2 was 5.7 ± 5.8% for T1, 2.5 ± 2% for T2, 7.10 ± 7.12% for T1ρ, 0.34 ± 0.36% for MTR, and 2.5 ± 2.8% for diffusion. The average interassay variation of the MR techniques determined from all standard solutions was 3.6 ± 2.1% for T1, 3.6 ± 2.0% for T2, 1.4 ± 0.6% T1ρ, 0.6 ± 0.2% for MTR, and 2.1 ± 0.6% for diffusion.

Total Water, Proteoglycan, Collagen, and Denatured Collagen Contents

After MRI, the NP and AF tissues were dissected from the discs and cut into two sections. One section was further dissected into two 10–30 mg specimens using a scalpel, while the second section was flash-frozen on dry ice and kept in foil at −80°C for mechanical testing. The matrix composition was determined as previously described (21,22). Briefly, the percent water content and dry tissue weight were determined by drying NP and AF specimens at 110°C for 4 days (until constant weight was obtained). The dried tissues were then digested by proteinase K to measure proteoglycan by the DMMB dye assay (27) and total collagen content using a colorimetric assay of the hydroxyproline content in the digested fractions (3,28). The second NP and AF specimens were digested by α-chymotrypsin followed by proteinase K to measure the percent of denatured collagen by the same colorimetric assay (3,28). Hydroxyproline content being equivalent to 10% of the weight of each collagen alpha chain, total collagen content per dry weight was estimated in the proteinase K-digested fraction of the dried tissue (28). The percent denatured collagen was calculated as the percent of collagen in the α-chymotrypsin fraction over that in both the α-chymotrypsin and proteinase K fractions.

Mechanical Testing Procedure

The frozen NP and AF tissue sections reserved for mechanical analysis were microtomed to a thickness (mean ± standard deviation) of 1.94 ± 0.29 and 2.08 ± 0.33 mm, respectively, and 5.0 mm-diameter plugs were taken with a biopsy punch. The specimens were then tested under confined compression as previously described (21). Briefly, the specimens were placed in a nonpermeable confined compression chamber and a permeable upper platen was lowered until a tare force of 0.1 N was achieved. Phosphate-buffered saline solution was then added to the chamber and the specimens were allowed to swell under constant displacement for 1000 seconds to achieve force equilibrium. NP specimens were then subjected to a series of four displacement controlled ramps corresponding to 10% strain increments, dwell periods of 1000, 1500, 2000, and 2500 seconds, and a strain rate of 0.0005 s−1. AF specimens also underwent a series of four displacement controlled ramps corresponding to 10% strain increments but dwell periods were of 2000, 3000, 4000, and 5000 seconds and the strain rate was of 0.00025 s−1. Swelling pressure was calculated based on the increase in measured force throughout the initial dwell period. Compressive modulus HA and hydraulic permeability k were computed as previously described (29).

Statistical Analysis

From preliminary studies with the same biochemical, mechanical, and MR properties (except T1ρ) measured on the NP tissue it was determined that the mechanical properties had the greatest variability and thus a minimum sample size of 12 was required to attain a power of at least 0.8 at a significance of 0.05. Hence, a total of 15 unloaded and 15 loaded discs with buffer-treated NPs, and 18 unloaded and 18 loaded discs with trypsin-treated NPs were used for the analyses. The same number of AF specimens was obtained, and since there were no statistical differences between results of the anterior and posterior AFs, the results were combined. Since the T1ρ technique was assessed only near the end of this project, effects were analyzed with four unloaded and four loaded discs with buffer-treated NPs and adjacent AFs, and five unloaded and five loaded discs with trypsin-treated NPs and adjacent AFs. This still provided a power of at least 0.8 to establish statistical significance in terms of the effect of loading, but a sample size of more than 100 would have been required to establish significance at such a power for the effect of trypsin treatment.

The effect of loading and trypsin treatment was analyzed separately using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When statistical significance was attained, the effects were further analyzed by subgroups. The dependent variables for the ANOVAs were the MR parameters: T1, T2, T1ρ, MTR, ADCx, ADCy, ADCz, and mean ADC, the biochemical properties: water, GAG, total collagen, and denatured collagen contents, and the mechanical properties: swelling pressure, HA, and k. Correlations were investigated between the above MR parameters and biochemical and mechanical properties using Pearson tests. Multiple linear regressions were performed between independent MR parameters and dependent biochemical and mechanical properties. Statistical significance (Statview v. 5.0.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was considered for P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Nucleus Pulposus Tissue

Changes in Relaxation Times, Magnetization Transfer Ratio, and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient

Figure 1 presents the results of the MRI analyses after cyclic compression loading of the 3-disc segments for 16 hours with NP treated without (buffer) or with trypsin. Of special interest here was the finding that loading significantly decreased T1 (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1a), T2 (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1b), T1ρ (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1c), and diffusion in all three orthogonal directions (ADCy, ADCz: P < 0.0001; ADCx: P < 0.02; Fig. 1e), and increased MTR (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1d) in the NP. However, trypsin treatment of NPs for 16 hours had no significant effect on MR parameters when compared to buffer treatment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of cyclic compression loading for 16 hours and trypsin treatment of the NP on the MR parameters of the NP tissue: (a) T1; (b) T2; (c) relaxation time in the rotating frame, T1ρ; (d) magnetization ratio, MTR; and (e) mean apparent diffusion coefficient, ADCmean. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences between experimental groups are indicated by *P < 0.0005, #P < 0.005, and $P < 0.05.

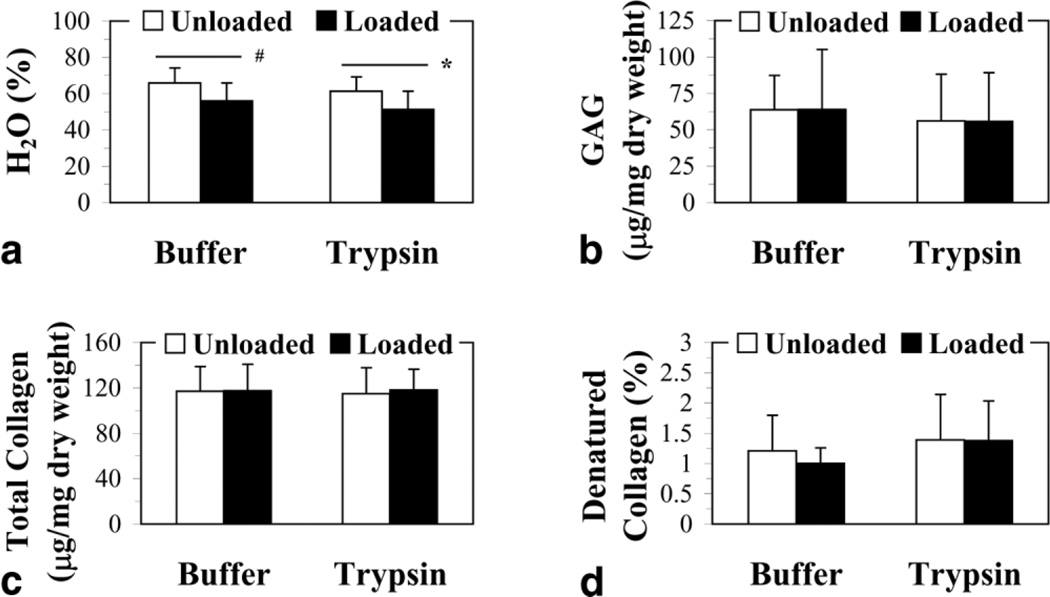

Water, Glycosaminoglycan, Total Collagen, and Denatured Collagen Content

The effects of load and trypsin treatment on the biochemical properties of the NP tissue are shown in Fig. 2. Here it is clear that loading significantly decreased the NP water content (P < 0.0001), whereas trypsin treatment tended to lower the water content (P < 0.06) but required the presence of loading to significantly decrease NP hydration (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2a). In contrast, GAG content did not change with loading (Fig. 2b). However, trypsin treatment decreased the GAG content when loading was present (P < 0.02) (Fig. 2b). Both load and trypsin treatment did not affect the total collagen content of the NP tissue (Fig. 2c). The NP denatured collagen content tended to increase with load (P<0.07), but it was rather the treatment of NPs with trypsin that led to a significantly greater denatured collagen content than in buffer-treated NPs, regardless of load (P = 0.0002) (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Effect of cyclic compression loading for 16 hours and trypsin treatment of the NP on the biochemical properties of the NP tissue: (a) water, H2O, (b) glycosaminoglycan, GAG, (c) total collagen, and (d) denatured collagen. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences between experimental groups are indicated by *P < 0.0005, #P < 0.01, and $P ≤ 0.05.

Swelling Pressure, Compressive Modulus, and Hydraulic Permeability

The effect of 16 hours of physiological compression loading as well as treatment of the NP tissue with trypsin on the mechanical properties was also examined (Fig. 3). Loading caused the swelling pressure (P < 0.002) (Fig. 3a) and the compressive modulus (P < 0.1) (Fig. 3b) to increase, particularly for the compressive modulus of buffer-treated NPs (P < 0.04), while the hydraulic permeability tended to decrease (P < 0.06), in this case particularly in the trypsin-treated NPs (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3c). On the other hand, trypsin treatment of NPs for 16 hours decreased both the swelling pressure (P < 0.003) (Fig. 3a) and the compressive modulus (P < 0.0008) (Fig. 3b), but tended to increase the hydraulic permeability (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3c), particularly in the NPs of unloaded discs (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect of cyclic compression loading for 16 hours and trypsin treatment of the NP on the mechanical properties of the NP tissue: (a) swelling pressure, P; (b) compressive modulus, HA; and (c) hydraulic permeability, k. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences between experimental groups are indicated by *P < 0.001, #P < 0.005, and $P < 0.05.

Correlations between Quantitative MR Parameters, the Biochemical Content, and the Mechanical Properties

The correlation values are presented in Table 1. In combining all groups, significant correlations were found between water content and the MR parameters of the NP, T1, T2, T1ρ, MTR, and mean ADC (this was also observed with diffusion in all three orthogonal directions). In further considering the NPs of the loaded IVDs, the significant correlations were mainly in terms of the mechanical properties. High positive correlations were found between the compressive modulus, T1, T1ρ, mean ADC (also in all three directions), and showed a trend with GAG. The hydraulic permeability tended to correlate with the biochemical properties, GAG and total collagen. There were also significant correlations with the loaded NPs of MTR with total collagen and denatured collagen. However, when the NPs of the unloaded discs were considered only, the above correlations were not observed; only k correlated with GAG and water.

Table 1.

Correlations between MR, Biochemical, Mechanical Parameters of Loaded, Unloaded, Trypsin-Treated, and Buffer-Treated NPs

|

All NP groups |

Loaded NP group |

Unloaded NP group |

Trypsin-treated NP group |

Buffer- treated NP group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | MTR | HA | k | k | H2O | P | HA | k | P | |

| MR Parameters | ||||||||||

| T1 | r = 0.757, P = 0.0002 | r =0.857, P =0.002 | r = 0.862, P = 0.0014 | r = −0.594, P = 0.094 | r = −0.823, P = 0.004 | r = 0.587, P = 0.099 | ||||

| T2 | r = 0.591, P = 0.011 | r = −0.685, P = 0.04 | r = 0.679, P = 0.043 | |||||||

| T1ρ | r = 0.595; P =0.01 | r =0.776, P =0.011 | r = 0.744, P = 0.019 | r = −0.641, P = 0.062 | r = 0.514, P = 0.005 | |||||

| MTR | r = −0.817, P < 0.0001 | r = −0.979, P < 0.0001 | r = 0.823, P = 0.0043 | r = 0.788, P = 0.009 | ||||||

| Mean ADC | r = 0.729, P = 0.0005 | r =0.753, P =0.016 | r = 0.854, P =0.002 | r = −0.679, P = 0.043 | r = −0.724, P = 0.025 | r = 0.533; P = 0.026 | ||||

| Biochemical parameters | ||||||||||

| H2O | r = −0.767, P = 0.024 | r = −0.965, P < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| GAG | r =0.650, P = 0.058 | r = −0.605, P = 0.086 | r = −0.705, P = 0.05 | |||||||

| Total collagen | r= −0.708, P = 0.031 | r = 0.657, P = 0.054 | ||||||||

| Denatured collagen | r = 0.688, P = 0.0386 | |||||||||

| Mechanical parameters | ||||||||||

| P | r = −0.847, P = 0.002 | |||||||||

| HA | r = −0.787, P = 0.009 | |||||||||

| k | r = 0.331, P = 0.019 | |||||||||

NP, nucleus pulposus; H2O, water; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; MTR, magnetization transfer ratio; Mean ADC, mean apparent diffusion coefficient; P, swelling pressure; HA, compressive modulus; k, hydraulic permeability.

The trypsin-treated NPs also showed significant correlations between MR parameters and water and/or mechanical properties: water correlated with T1, MTR, T1ρ, mean ADC (also in all three directions), the swelling pressure, HA, and weakly with k. The swelling pressure correlated with MTR, mean ADC, and tended to correlate with T1. The compressive modulus of trypsin-treated NPs strongly correlated with T1, MTR, mean ADC (also in all three directions), and moderately with T2 and T1ρ. The hydraulic permeability significantly correlated with T2, T1ρ, mean ADC, and tended to correlate with T1. No significant correlations were found between MR parameters, biochemical and mechanical properties of buffer-treated NPs, except between the swelling pressure and water content.

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

The multiple linear regressions between the biochemical content or the mechanical properties of the NP and the MR parameters showed that:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where H2O is in percent, k in 10−15 m4/Ns, T1, T2, and T1ρ in msec, ADCmean in 10−3 mm2/s, and MTR is a ratio.

Annulus Fibrosus Tissue

Changes in Relaxation Times, Magnetization Transfer Ratio, and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient

The effect of 16 hours of cyclic compression loading and trypsin treatment of the NP on the MR parameters of the adjacent AF tissue was also examined (Fig. 4). Loading decreased T1 (P < 0.0001; Fig. 4a), T1ρ (P < 0.0001; Fig. 4c), and increased MTR (P < 0.01; Fig. 4d). Interestingly, there was a trend toward an increase in T2 with load but this was not significant when the AFs adjacent to the buffer- and trypsin-treated NPs were analyzed separately (P < 0.1; Fig. 4b). Treatment with trypsin did not significantly affect any of the MR parameters measured.

Figure 4.

Effect of cyclic compression loading for 16 hours and trypsin treatment of the NP on the MR parameters of the adjacent AF tissue: (a) T1; (b) T2; (c) relaxation time in the rotating frame, T1ρ; and (d) magnetization ratio, MTR. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences between experimental groups are indicated by *P < 0.0005, #P < 0.005, and $P < 0.05.

Water, Glycosaminoglycan, Total Collagen, and Denatured Collagen Content

When the biochemical properties of the AF tissue were analyzed after 16 hours of compression loading we observed that only the AF water content decreased (P < 0.0003; Fig. 5a). Trypsin treatment of the NP, even in the presence of loading, did not lead to any significant changes in the biochemical content of the surrounding AF tissue (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of cyclic compression loading for 16 hours and trypsin treatment of the NP on the biochemical properties of the adjacent AF tissue: (a) water, H2O; (b) glycosaminoglycan, GAG; (c) total collagen; and (d) denatured collagen. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences between experimental groups are indicated by *P < 0.01 and #P < 0.05.

Swelling Pressure, Compressive Modulus, and Hydraulic Permeability

Analysis of the mechanical properties of the AF tissue after 16 hours of cyclic compression loading showed that the swelling pressure tended to increase when loading was applied (P < 0.02; Fig. 6a), but when the AFs adjacent to the buffer- and trypsin-injected NPs were analyzed separately this significant difference was lost (buffer: P < 0.07; trypsin: P < 0.2). Loading also led to an increase in the AF compressive modulus (P < 0.03; Fig. 6b) and this effect was more evident in the AFs adjacent to trypsin-treated NPs (P < 0.007). Interestingly, the hydraulic permeability of the AF tissue appeared to increase with load (P < 0.05; Fig. 6c). Injection of trypsin in the NP appeared to affect only the swelling pressure of the adjacent AF tissue, but this was not significant (P < 0.1; Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

Effect of cyclic compression loading for 16 hours and trypsin treatment of the NP on the mechanical properties of the adjacent AF tissue: (a) swelling pressure, P; (b) compressive modulus, HA; and (c) hydraulic permeability, k. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences between experimental groups are indicated by *P < 0.01 and #P < 0.05.

Correlations between Quantitative MR Parameters, the Biochemical Content, and the Mechanical Properties

The correlation values are presented in Table 2. When all AF groups were combined, the only significant correlations observed were between water and T1 and T1ρ. When groups were subdivided, the loaded AFs had a significant correlation between the hydraulic permeability and T1ρ, and tended to show correlations between water and T1, and HA and T1, total collagen, and denatured collagen. The unloaded AFs had the following correlations or trends: water and MTR, GAG and MTR, and denatured collagen and T1.

Table 2.

Correlations between MR, Biochemical, Mechanical Parameters of Loaded and Unloaded AFs

|

All AF groups |

Loaded AF group | Unloaded AF group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | H2O | HA | k | MTR | Denatured collagen |

|

| MR parameters | ||||||

| T1 | r = 0.669, P = 0.0025 | r = 0.647, P = 0.059 | r = 0.638, P = 0.06 | r = −0.677, P = 0.065 | ||

| T2 | ||||||

| T1ρ | r = 0.588, P = 0.012 | r = −0.768, P = 0.013 | ||||

| Biochemical parameters | ||||||

| H2O | r = 0.731, P = 0.037 | |||||

| GAG | r = 0.669, P = 0.071 | |||||

| Total collagen | r = 0.609, P = 0.083 | |||||

| Denatured collagen | r = 0.609, P = 0.083 | |||||

AF, annulus fibrosus; H2O, water; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; MTR, magnetization transfer ratio; HA, compressive modulus; k, hydraulic permeability.

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

The multiple linear regressions between the biochemical or mechanical properties and the MR parameters showed the following relations for AF:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where H2O is in percent, swelling pressure in 10−8 Pa, T1, T2, and T1ρ in msec, and MTR is a ratio.

DISCUSSION

While disc pathology treatment is shifting toward prevention and treatment of underlying etiologic processes at the level of the disc matrix composition and integrity, few studies have been directed toward developing quantitative MRI as an objective, accurate, and noninvasive diagnostic tool in the detection and quantification of matrix (composition and integrity) and mechanical changes in early IVD degeneration. The initial goals of the present work were 1) to establish correlations between MR parameters and the biochemical and mechanical properties of the NP undergoing targeted trypsin digestion and axial compression at forces corresponding to 1 MPa loaded at 1 Hz for 16 hours in saline solution; 2) to correlate matrix and structural changes in the AF tissue due to mechanical loading to MR parameters, and to determine if targeted trypsin digestion of the NP affected the biochemical, mechanical, and MR properties of the adjacent AF tissue; 3) to evaluate the sensitivity of T1ρ to IVD composition and to its structural integrity by evaluating its relationship with mechanical loading and biochemical composition.

In this report we demonstrate that MR parameters were influenced by compression loading for both the NP and AF tissues. Indeed, loading had a greater effect on the MR parameters and biochemical composition of the NP tissue than did trypsin digestion. On the other hand, swelling pressure, compressive modulus, and hydraulic permeability analyses revealed that trypsin had a larger effect on the mechanical properties of the NP tissue than did loading. Injection of the NP tissue with trypsin did not lead to its diffusion into the adjacent AF tissue, even after 16 hours of compression loading, since the biochemical and mechanical properties of the AF tissue were not affected and this was reflected in the absence of changes in MR parameters. We also show that T1ρ is sensitive to compression loading and correlated with the water content of the NP and AF tissues but not with their proteoglycan content.

A previous study showed that trypsin treatment of the NP during 2 hours of cyclic compression loading affected its mechanical properties, but not its MR parameters (21), suggesting that the mechanical properties must be more sensitive to the structural changes induced by trypsin treatment. Furthermore, although trypsin induced degradation of the proteoglycans (confirmed by composite agarose-SDS PAGE electrophoresis gels), the MR properties of NPs in a closed and static system were not affected (22). The results lead us to conclude that addition of physiological compression loading is not sufficient to enable quantitative MRI to directly detect changes in matrix composition induced by targeted degradation of the NP with trypsin. However, the three parameters of relaxation as well as the ADCs correlated with the compressive modulus and hydraulic permeability of trypsin-treated NPs, but these correlations were absent in buffer-treated NPs. Hence, targeted degradation of the proteoglycan core protein by trypsin directly affects the structural integrity of the disc, as measured by confined compression tests, which in turn correlate to MR parameters. Since the above MR and mechanical properties both also correlated with the water content of trypsin-digested NPs, this could potentially allow the detection by quantitative MRI of changes in matrix composition and structure as a result of proteoglycan cleavage. It remains to be determined whether the effects of other enzymes that target the collagen network such as collagenase, which are detected by quantitative MRI (22), are directly influenced by mechanical loading.

In the present study, the MR parameters of the disc were influenced by compression loading. Trends were generally similar for both the NP and AF tissues: T1 and T1ρ decreased while MTR increased with load. It has previously been shown that T1 and T2 decrease with loading, and MTR increases with loading (21). MTR also increases during mechanical compression of articular cartilage (30). This increase may be due not only to an increase in collagen content as a result of water loss but also to an increase in the collagen-bound water fraction as a result of the closer packing of the collagen fibers, and to changes in the macromolecular arrangement (30). In the present study, loading also led to a decrease in T2 and diffusion coefficients of the NP tissue only. The diffusion coefficients could not be measured for the AF tissue since the resolution of the diffusion images was too low in this region. T2 has been shown in the past to vary due to spins dephasing differently as a result of differing mechanisms (31). Hence, T2 has been shown to be influenced by tissue anisotropy (orientation of collagen fibers), collagen concentration, and water content in tissues (17,31). In the present work, T2 correlated with disc tissue hydration.

Our studies with T1ρ clearly revealed that it did not correlate with proteoglycan content (GAG), but rather with water content in both disc tissues. This is contrary to what was expected and to what was found in previous studies on IVD (20) and cartilage tissues (32–34). In one study (32), they correlated the changes in cartilage mechanical and biochemical properties with T1ρ relaxation rate (1/T1ρ) in a cytokine-induced model of degeneration. The results indicated that T1ρ can detect changes in the proteoglycan content and biomechanical properties of cartilage in this model. In another study, it was shown that T1ρ-weighted imaging can be sensitive to sequential depletion of proteoglycan in bovine cartilage and can be used to quantify proteoglycan-induced changes (33). Similarly, work by Wheaton et al (34) implemented the T1ρ technique in an in vivo porcine animal model with rapidly induced recombinant porcine interleukin-1β-mediated cartilage degeneration. The results from this study demonstrate that T1ρ can track proteoglycan content in vivo. However, other work implies that T1ρ is sensitive to biologically meaningful changes in cartilage, but is not specifically associated with any one inherent tissue parameter (35). They showed that T1ρ is affected by the concentration, particularly of collagen, as well as by changes at the molecular level, and that hydration and structure also play a role (35). In the present study the small sample size may explain the lack of correlation between T1ρ and proteoglycan content. However, changes in hydration of the disc tissues as a result of loading and trypsin treatment appear to have been greater than changes in proteoglycan content, thus explaining the observed correlation between T1ρ and water content with the present sample size.

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that T1ρ is influenced by loading of the IVD. Furthermore, the compressive modulus of loaded NP tissue correlated with T1 and T1ρ, while the hydraulic permeability of loaded AF tissue inversely correlated with T1ρ. Wheaton et al (32) have recently shown that the T1ρ relaxation rate correlates with the compressive modulus and the negative logarithm of the hydraulic permeability of bovine articular cartilage treated with and without interleukin 1β. This is interesting since it translates into correlations for T1ρ that are opposite to those observed in the present study. There are, however, three differences between the two experiments. Although IVDs often behave like articular cartilage, this composite tissue has a different structural composition and different functions. Further, the correlations established with the articular cartilage tissue used data from nontreated and interleukin 1β-treated samples, while in the present study the data were obtained from loaded trypsin-treated and nontreated disc tissue. Although the principal effect of both treatments was to decrease the GAG content, there were also other changes in the matrix composition of the cartilage and disc tissues that differed. Finally, we were not able to establish the same correlations in unloaded disc tissues, reinforcing the fact that loading played an important role on the correlations that were established between T1ρ and the compressive properties of the disc tissues.

In conclusion, it is evident that loading of both the NP and AF tissues induced significant changes on their MR properties (T1, T2, T1ρ, MTR, and diffusion—measured in NP tissue only), water content, and mechanical properties. Trypsin predominantly affected the mechanical properties of the NP tissue, while its biochemical and MR properties were more sensitive to compression loading. Since treatment of the NP tissue with trypsin affected the biochemical and mechanical properties only of the NP tissue and not of the adjacent AF tissue, it may be concluded that loading does not enhance the transport of the trypsin enzyme beyond its injected area of the NP tissue. It remains, however, to be determined if similar observations can be made when enzymes that specifically target the collagen network, which predominates in the AF tissue, are used with the present experimental design. Finally, this study demonstrates specific correlations between T1ρ and the structural and compositional changes in the disc. Further studies are required to determine the potential of the T1ρ technique to be used as a noninvasive diagnostic tool of the biochemical and mechanical changes occurring in disc degeneration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Arijitt Borthakur from the Department of Radiology at the University of Pennsylvania for the T1ρ protocol.

Contract grant sponsor: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Contract grant sponsor: McGill William Dawson Scholar Award; Contract grant sponsor: Whitaker Foundation; Contract grant sponsor: AO Foundation (Switzerland); Contract grant number: F-06-31A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biering-Sorensen F. Low back trouble in a general population of 30-, 40-, 50-, and 60-year-old men and women. Study design, representativeness and basic results. Dan Med Bull. 1982;29:289–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spengler DM, Bigos SJ, Martin NA, Zeh J, Fisher L, Nachemson A. Back injuries in industry: a retrospective study. I. Overview and cost analysis. Spine. 1986;11:241–245. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burleigh MC, Barrett AJ, Lazarus GS. Cathepsin B1. A lysosomal enzyme that degrades native collagen. Biochem J. 1974;137:387–398. doi: 10.1042/bj1370387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler D, Trafimow JH, Andersson GB, McNeill TW, Huckman MS. Discs degenerate before facets. Spine. 1990;15:111–113. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199002000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luoma K, Riihimaki H, Luukkonen R, Raininko R, Viikari-Juntura E, Lamminen A. Low back pain in relation to lumbar disc degeneration. Spine. 2000;25:487–492. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200002150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kauppila LI, McAlindon T, Evans S, Wilson PW, Kiel D, Felson DT. Disc degeneration/back pain and calcification of the abdominal aortaA 25-year follow-up study in Framingham. Spine. 1997;22:1642–1647. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199707150-00023. discussion 1648–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oegema TR., Jr Biochemistry of the intervertebral disc. Clin Sports Med. 1993;12:419–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi T, Kurihara H, Nakajima S, et al. Chemonucleolytic effects of chondroitinase ABC on normal rabbit intervertebral discs. Course of action up to 10 days postinjection and minimum effective dose. Spine. 1996;21:2405–2411. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199611010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasuma T, Koh S, Okamura T, Yamauchi Y. Histological changes in aging lumbar intervertebral discs. Their role in protrusions and prolapses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:220–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Happey F, Pearson CH, Naylor A, Turner RL. The ageing of the human intervertebral disc. Gerontologia. 1969;15:174–188. doi: 10.1159/000211685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernick S, Walker JM, Paule WJ. Age changes to the anulus fibrosus in human intervertebral discs. Spine. 1991;16:520–524. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199105000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derian TC. Adjacent disc degeneration in patients with prior spinal fusion procedures. Spine. 1994;19:2244–2245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CK. Accelerated degeneration of the segment adjacent to a lumbar fusion. Spine. 1988;13:375–377. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198803000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips FM, Reuben J, Wetzel FT. Intervertebral disc degeneration adjacent to a lumbar fusion. An experimental rabbit model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:289–294. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b2.11937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paajanen H, Komu M, Lehto I, Laato M, Haapasalo H. Magnetization transfer imaging of lumbar disc degeneration. Correlation of relaxation parameters with biochemistry. Spine. 1994;19:2833–2837. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199412150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tertti M, Paajanen H, Laato M, Aho H, Komu M, Kormano M. Disc degeneration in magnetic resonance imaging. A comparative bio-chemical, histologic, and radiologic study in cadaver spines. Spine. 1991;16:629–634. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antoniou J, Pike GB, Steffen T, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of degenerative disc disease. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40:900–907. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antoniou J, Demers CN, Beaudoin G, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient of intervertebral discs related to matrix composition and integrity. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22:963–972. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerttula L, Kurunlahti M, Jauhiainen J, Koivula A, Oikarinen J, Tervonen O. Apparent diffusion coefficients and T2 relaxation time measurements to evaluate disc degeneration. A quantitative MR study of young patients with previous vertebral fracture. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:585–591. doi: 10.1080/028418501127347241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johannessen W, Auerbach JD, Wheaton AJ, et al. Assessment of human disc degeneration and proteoglycan content using T1rho-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 2006;31:1253–1257. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000217708.54880.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perie D, Iatridis JC, Demers CN, et al. Assessment of compressive modulus, hydraulic permeability and matrix content of trypsin-treated nucleus pulposus using quantitative MRI. J Biomech. 2006;39:1392–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antoniou J, Mwale F, Demers CN, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of enzymatically induced degradation of the nucleus pulposus of intervertebral discs. Spine. 2006;31:1547–1554. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000221995.77177.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferguson SJ, Ito K, Nolte LP. Fluid flow and convective transport of solutes within the intervertebral disc. J Biomech. 2004;37:213–221. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berg A, Singer T, Moser E. High-resolution diffusivity imaging at 3.0 T for the detection of degenerative changes: a trypsin-based arthritis model. Invest Radiol. 2003;38:460–466. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000078762.72335.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weidenbaum M, Foster RJ, Best BA, et al. Correlating magnetic resonance imaging with the biochemical content of the normal human intervertebral disc. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:552–561. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubenstein JD, Kim JK, Morova-Protzner I, Stanchev PL, Henkel-man RM. Effects of collagen orientation on MR imaging characteristics of bovine articular cartilage. Radiology. 1993;188:219–226. doi: 10.1148/radiology.188.1.8511302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farndale RW, Buttle DJ, Barrett AJ. Improved quantitation and discrimination of sulphated glycosaminoglycans by use of dimethylmethylene blue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;883:173–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nimni ME. Collagen: structure, function, and metabolism in normal and fibrotic tissues. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1983;13:1–86. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(83)90024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mow VC, Kuei SC, Lai WM, Armstrong CG. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression? Theory and experiments. J Biomech Eng. 1980;102:73–84. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Regatte RR, Akella SV, Reddy R. Depth-dependent proton magnetization transfer in articular cartilage. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:318–323. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosher TJ, Dardzinski BJ. Cartilage MRI T2 relaxation time mapping: overview and applications. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2004;8:355–368. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-861764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wheaton AJ, Dodge GR, Elliott DM, Nicoll SB, Reddy R. Quantification of cartilage biomechanical and biochemical properties via T1rho magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1087–1093. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regatte RR, Akella SV, Borthakur A, Kneeland JB, Reddy R. Proteoglycan depletion-induced changes in transverse relaxation maps of cartilage: comparison of T2 and T1rho. Acad Radiol. 2002;9:1388–1394. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wheaton AJ, Dodge GR, Borthakur A, Kneeland JB, Schumacher HR, Reddy R. Detection of changes in articular cartilage proteoglycan by T1rho magnetic resonance imaging. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menezes NM, Gray ML, Hartke JR, Burstein D. T2 and T1rho MRI in articular cartilage systems. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:503–509. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]