Abstract

Clinical and counseling psychology programs currently lack adequate evidence-based competency goals and training in suicide risk assessment. To begin to address this problem, this article proposes core competencies and an integrated training framework that can form the basis for training and research in this area. First, we evaluate the extent to which current training is effective in preparing trainees for suicide risk assessment. Within this discussion, sample and methodological issues are reviewed. Second, as an extension of these methodological training issues, we integrate empirically- and expert-derived suicide risk assessment competencies from several sources with the goal of streamlining core competencies for training purposes. Finally, a framework for suicide risk assessment training is outlined. The approach employs Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) methodology, an approach commonly utilized in medical competency training. The training modality also proposes the Suicide Competency Assessment Form (SCAF), a training tool evaluating self- and observer-ratings of trainee core competencies. The training framework and SCAF are ripe for empirical evaluation and potential training implementation.

Keywords: suicide, risk assessment, competency, psychology training, OSCE

In 2010, suicide was the tenth leading cause of death for people of all ages, claiming over 38,000 Americans (Hoyert & Xu, 2011). Practicing mental health professionals will almost certainly encounter a suicidal patient, considering the high prevalence of suicide within psychiatric populations. Indeed, surveys have suggested that one out of four trainees may need to cope with a suicide attempt of one of their patients during clinical training, and one out of nine will cope with a suicidal completion (Kleespies, Smith, & Becker, 1990). Moreover, trainees who experienced a completed patient suicide were significantly more distressed than those who dealt with suicidal ideation (Kleespies, Penk, & Forsyth, 1993). Although some of the extant knowledge in this area may be dated, there appears an overall issue of need for clinical and counseling psychology doctoral training in suicide risk assessment (Schmitz et al., 2012).

Estimating suicide risk, inclusive of arriving at a risk level judgment and developing an intervention plan, is an important step in the prevention of suicide. Therefore, both suicide risk estimation and intervention planning are included where we use phrasing of suicide risk assessment throughout the duration of this article. Recommendations exist for more accurate risk assessment procedures accounting for both the low rate of occurrence and clinician tendency to be too conservative or liberal in their subjective assessments (Bryan & Rudd, 2006). An additional fact exacerbating poor prediction of risk is the lack of requirement in the education of mental health professionals that includes suicide risk assessment. Although there is a lack of comprehensive data on the subject, the limited available data suggest that only 40% to 50% of graduate training programs in clinical and counseling psychology include formal training on suicide risk assessment and management (Bongar & Harmatz, 1991; Dexter-Mazza & Freeman, 2003; Reeves, Wheeler, & Bowl, 2004). Where training does exist, many psychology internship trainees indicate that training is of low or poor quality (Ellis & Dickey, 1998). More recent evidence shows that 86.6% of mental health professionals surveyed reported a desire to improve their competence in suicide risk assessment (Palmieri et al., 2008). Collectively, this body of work shows that, despite beginning efforts in suicide risk assessment training, there is still a need to refine training methods and integrate evidence-based data and practices (e.g., Ellis, Green, Allen, Jobes, & Nadoff, 2012; Rudd, 2006) into clinical and counseling psychology training.

We aim to contribute to filling the gap in literature on suicide risk assessment training for psychology doctoral programs in three ways. First, we evaluate the extent to which current training is effective in preparing trainees for suicide risk assessment. Within this discussion, sample and methodological issues are reviewed. Second, as an extension of these methodological training issues, we integrate expert-derived suicide risk assessment competencies from several sources with the goal of streamlining core competencies for training purposes. Finally, extrapolating from medical training literature, we propose an evidence-based framework for suicide risk assessment training utilizing self- and observer-effectiveness ratings and standardized methods of training.

Suicide Risk Assessment Training: Effectiveness and Limitations

Extant evidence on effectiveness of suicide risk assessment training is limited to medical (primarily psychiatric) education programs by addressing outcomes such as subjective confidence in trainee abilities and objective ratings of competency mastery. The types of training that have been used in studies include intense 3-hr workshops (e.g., McNiel et al., 2008), 1 to 2 day workshops (e.g., Oordt, Jobes, Fonseca, & Schmidt, 2009), or 6 to 8 hours of training split over many sessions over time (e.g., Appleby et al., 2000; Morriss, Gask, Battersby, Francheschini, & Robson, 1999). Subjective data suggests that training enhances the confidence mental health professionals have in their accuracy of risk estimates and management planning (Fenwick, Vassilas, Carter, & Haque, 2004; Oordt et al., 2009), though other existing data suggests that such gains may only be temporary (Rutz, von Knorring, & Walinder, 1989; Szanto, Kalmar, Hendin, Rihmer, & Mann, 2007). In perhaps the most comprehensive review of workshop style suicide risk assessment training, Pisani, Cross, and Gould (2011) concluded that these workshops generally demonstrate desired impact of enhancing clinician knowledge and attitudes. However, the state of the empirical knowledge about suicide training workshops in enhancing care and suicide prevention still needs work. Also, as evaluated by expert raters among other evaluative mechanisms, training in suicide risk assessment and intervention planning has been shown to increase the quality of interviews and documentation (Hung et al., 2012; McNiel et al., 2008).

Despite some promising results of this body of literature, a multitude of limitations make it difficult to evaluate effectiveness of suicide risk assessment training programs. The most obvious drawback is seen in the lack of the ultimate dependent measure: prevention of death by suicide. Because of low base rates and other methodological concerns, this problem may be a difficult one to address as suicide risk assessment training research moves forward. Current training research also possesses sampling concerns; specifically, samples are mostly limited to medical/psychiatric settings and trainees (e.g., Hung et al., 2012). Germane to psychology training, most studies lack any psychology trainees and those that do include them show a single digit number of such participants (e.g., Fenwick et al., 2004; McNiel et al., 2008). Although clinical/counseling psychologists and medical professionals face many of the same issues when assessing risk, there are also distinct, profession-specific issues that should be incorporated in training for psychology trainees (e.g., evidenced-based psychological assessment and psychotherapy for suicide). Only one study (i.e., Oordt et al., 2009) exists supporting the conclusion that evidence-based suicide risk assessment training improves ability and confidence among clinical psychology trainees. This training program, however, was specific to a military setting.

Additional methodological issues exist. For instance, many program evaluations lack comparison groups (e.g., Oordt et al., 2009) or have quite small comparisons (e.g., McNiel et al., 2008). Even when longitudinal data were collected on the efficacy of such programs (e.g., Oordt et al., 2009), lack of a comparison group limits the ability of researchers to conclude that the ability to conduct effective suicide risk assessments is due to the specific training experience as opposed to other learning opportunities There is also a lack of consistency in the content and method of training. Very few (e.g., Hung et al., 2012) focus on evidence-based core competencies for risk assessment, and where competency-based training is implemented, those competencies differ greatly (e.g., Hung et al., 2012 vs. King, Lloyd, Meehan, O’Neill, & Wilesmith, 2006). There is a clear need to identify a streamlined list of core competencies for concise yet comprehensive training. An additional disparity is that some types of programs utilize psychoeducational workshops and role plays (e.g., Oordt et al., 2009), whereas others integrate more involved vignette (e.g., McNiel et al., 2008) or videotaped interview strategies (e.g., Hung et al., 2012; Morriss et al., 1999).

It is again noteworthy that no existing training methods have been investigated specifically in traditional clinical or counseling psychology training settings and samples. To help establish groundwork for such future research, we provide a discussion below of two foundational aspects of training. First, we discuss core competencies in suicide risk assessment based on established empirically driven (e.g., Ellis et al., 2012; Rudd, 2006) and expert-derived (e.g., Sullivan & Bongar, 2009) sources. Then, we review potential training methods to be applied to doctoral psychology programs.

Competencies in Suicide Risk Assessment

The need for, and movement toward, competency-based training in clinical and other domains of psychology is well documented by scholars and practitioners (e.g., Belar, 2009; Kenkel & Peterson, 2009). In line with this movement, we review several perspectives on suicide risk assessment competencies toward the end of identifying those most commonly cited for training purposes. Expert sources proffer various lists of suicide core competencies. These lists are most often derived from literature reviews, focus groups, and consultation with experts (e.g., American Association of Suicidology (AAS), 2010; Rudd, Cukrowicz, & Bryan, 2008). Although there is a high degree of agreement between sources, existing competencies suffer from an unwieldy number for training and practice purposes. The sources reviewed below were obtained through literature searches of PsycINFO and Psycharticles databases, consultation with experts in the field, as well as direct contact or collaboration with authors of relevant scholarship.

Perhaps the most prominent of these sources is the 24 Core Competencies for the Assessment and Management of Individuals at Risk for Suicide (AAS, 2010; Rudd et al., 2008). The first cluster of these competencies centering on a clinician’s attitudes and approach to suicidal individuals are: to manage one’s own reactions to suicide, reconcile the difference (and potential conflict) between the clinician’s goal to prevent suicide and the client’s goal to eliminate psychological pain via suicidal behavior, maintain a collaborative, nonadversarial stance, and finally make a realistic assessment of one’s ability and time to assess and care for a suicidal client. The second cluster of competencies focuses on understanding suicide as follows: be able to define basic terms related to suicidality (ideation, lethality, etc.), describe the phenomenology of suicide, and demonstrate understanding of risk and protective factors.

The next section addresses five competencies for collecting accurate assessment information: integrate a risk assessment for suicidality early on in a clinical interview, regardless of the setting in which the interview occurs, and continue to collect assessment information on an ongoing basis. Also important in the area of assessment are eliciting risk and protective factors, explaining the nature of suicide ideation, behaviors, and plans, drawing out warning signs of imminent risk of suicide, and obtaining records and information from collateral sources as appropriate. Formulating risk is another cluster of competencies the AAS has outlined. A clinician should make a clinical judgment of the risk that a client will attempt or complete suicide in the short and long term. This should be written in the client’s record, including a rationale of the judgment.

The next cluster of competencies focuses on developing treatment and service plans: collaboratively develop an emergency plan that assures safety and conveys the message that the client’s safety is not negotiable, a written treatment and services plan should be written that addresses the client’s immediate, acute, and continuing suicide ideation and risk for suicide behavior, coordination and collaboration with other treatment and service providers should be utilized in an interdisciplinary team approach. Related to care planning, managing care is the next cluster of competencies; clinicians should develop policies and procedures for following clients closely including taking reasonable steps to be proactive, the principles of crisis management should be followed, and documentation should be made concerning informed consent, bio-psychosocial information, formulation of risk and rationale, treatment and services plan, management, interaction with professional colleagues, and progress and outcomes should all be documented.

Finally, understanding legal and ethical issues related to suicidality is an important competency when dealing with suicidal clients. A mental health professional should understand state laws pertaining to suicide, comprehend legal challenges that are difficult to defend against as a result of poor or incomplete documentation, and protect client records and rights to privacy and confidentiality following the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 that went into effect April 15, 2003.

Other scholars have proposed different competencies practitioners should implement in order to estimate and manage suicide risk. Although some are espoused in list format in a manner consistent with the AAS (e.g., Sullivan & Bongar, 2009), other commentary articulates suicide risk assessment guidelines in larger discussions. For example, Joiner (2005) lays out expectations of the competent clinician in his broader review of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide. Moreover, Rudd (2006) proffers empirically derived guidance in a larger discussion on current knowledge of suicide risk assessment and management. Kleespies (1993) and Kleespies, Hough, and Romeo (2009), although not explicitly offering a list of competencies, also offer insight specific to the context of clinical training.

Table 1 contains suicide risk assessment competencies offered by each of these five sources. Each row contains all competencies concerning a particular theme. For instance, the first row contains all expressed competencies from these sources concerning monitoring one’s personal (i.e., internal and external) attitudes and reactions to suicide. In deriving the list of core competencies, we considered the extent to which a theme commonly emerged across multiple expert sources, as well as the significance of that domain in successfully navigating suicide risk assessment. As becomes evident from examining Table 1 and in the discussion of the rationales of the 10 core competencies below, the current state of suicide risk assessment competencies is both unwieldy and unnecessarily complex. Below we streamline this list into 10 manageable core competencies, with thematic explanation for each. These can form the foundation for a training framework for clinical psychology trainees (discussed later).

Table 1.

Comparison of Sources of Suicide Risk Assessment Competencies

| AAS, 2010 | Joiner, 2005 | Sullivan & Bongar, 2009 | Kleespies et al., 1993, 2009 | Rudd, 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Manage reactions to suicide. | 1. Clinician should be aware of their own reactions: do not be an “alarmist” or dismissive. | |||

| 2. Reconcile clinician’s goal to prevent suicide and client’s goal to eliminate psychological pain. | ||||

| 3. Maintain a collaborative, nonadversarial stance. | 1. Develop a good quality, ongoing, long term relationship with the client, marked by a positive alliance. | |||

| 4. Make a realistic assessment of one’s ability to care for a suicidal client. | 2. Have a list of other professionals that are available for consultation. | |||

| 5. Define basic terms related to suicidality. | 3. Be clear and precise with suicide terminology. | |||

| 6. Be familiar with suicide-related statistics. | ||||

| 7. Describe phenomenology of suicide. | ||||

| 8. Demonstrate understanding of risk and protective factors. | 1. Understand that having a physical illness (e.g., HIV/ AIDS, cancer, TBI, etc.) can be a risk factor for suicide especially early in the onset. High risk of suicide when depression in combined with medical illness. | 4. Consider risk factors such as: loss, health problems, Axis I and Axis II diagnosis, and family conflict. | ||

| 9. Integrate a risk assessment and continue to collect assessment information. | 1. Do a complete diagnostic assessment. 1.a. Psychological testing. |

5. Do a thorough history and interview. 5.a. Ask about suicidal history and address every suicidal crisis in detail. 5.b. Ask about current situation, especially in terms of frequency, intensity, duration, when, where, and access to method. |

||

| 10. Elicit risk and protective factors. | 2. Identify three main risk factors: ability to commit suicide (including multiple attempts), thwarted belonging, and perceived burdensomeness. | 1.b. Assess for mental disorders. 1.c. Assess for “accelerants” (i.e. insomnia, substance use, pain, personal loss, hopelessness, etc.) 2. Determine risk and protective factors. |

6. Identify risk factors. 7. Assess for protective factors, especially social support and the therapeutic relationship. |

|

| 11. Elicit suicide ideation, behaviors, and plans. | 3. Specifically address the client’s ability to commit suicide. Discuss resolved plans, preparations, and a desire for suicide. | 3. Ask directly about suicide. 3.a. Assess suicidal ideation. 3.b. Assess for previous suicide attempts and behavior. |

||

| 12. Elicit warning signs of imminent risk of suicide. | - | |||

| 13. Obtain records and information from collateral sources as appropriate. | - | |||

| 14. Make a clinical judgment of the risk that a client will attempt or complete suicide in the short and long term. | 4. Make a judgment of risk while continuing to monitor level of risk as risk level can change with fluctuations in dynamic risk factors. | 4. Determine level of risk. | 8. Determine risk level based on a continuum (e.g., minimal, mild, moderate, severe, and extreme), increasing as intent and symptom severity increases. | |

| 15. Write the judgment and the rationale in the client’s record. | 9. Thoroughly and clearly document thought processes, decisions, and assessments. Include direct quotes when useful/necessary. | |||

| 16. Collaboratively develop an emergency plan that assures safety and conveys the message that the client’s safety is not negotiable. | 10. Create a crisis plan with all clients. | |||

| 17. Develop a written treatment and services plan that addresses the client’s immediate, acute, and continuing suicide ideation and risk for suicide behavior. | 5. Enact an intervention to minimize distress in session (i.e. symptom matching hierarchy, creating a crisis card, etc.) 6. Develop suicide-specific therapeutic intervention plan: I: Identification of a negative thought C: Connection of the thought to broad categories of cognitive distortion A: Assessment of the thought R: Restructuring the thought E: Execute |

5. Make a treatment plan. | ||

| 18. Coordinate and work collaboratively with other treatment and service providers in an interdisciplinary team approach. | 5.a. Consider psychiatric medication and/or hospitalization. | |||

| 19. Develop policies and procedures for following clients closely including taking reasonable steps to be proactive. | - | 5.b. Get others involved in a client’s care. | ||

| 20. Follow principles of crisis management. | - | 11. Respond as needed based on risk level. | ||

| 21. Document the following items related to suicidality: informed consent, information that was collected from a bio-psychosocial perspective, formulation of risk and rationale, treatment and services plan, management, interaction with professional colleagues, and progress and outcomes. | - | 12. Document everything, including: discussion of any and all suicidal crises and suicidal ideation, crisis plan, treatment plan, rationale for risk level and intervention, all consultations, etc. | ||

| 22. Understand State laws pertaining to suicide. | ||||

| 23. Understand legal challenges that are difficult to defend against as a result of poor or incomplete documentation. | 13. Keep documentation accurate and specific as to not be misleading if case notes are needed in legal matters. | |||

| 24. Protect client records and rights to privacy and confidentiality following The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 that went into effect April 15, 2003. | ||||

| 7. Know and follow the standards of care for treatment and assessment of suicidality, but also be aware of the limits of intervention and people’s autonomy. | 2. Clinician should take advantage of coping strategies like social support (e.g., supervisor, peers, family, friends, and significant others), meeting the patient’s family or attending a post-mortem conference (if a patient completes suicide), also a case conference to review the case has been found to be helpful. |

1. Know and Manage Your Attitude and Reactions Toward Suicide When With a Client

Awareness and management of one’s personal attitudes and reactions toward suicide when with a client was a theme noted across several expert sources (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005; Rudd, 2006). Personal characteristics, such as spiritual affiliation and experience with loss, can affect one’s attitudes toward suicide. Clinicians are encouraged to reflect upon their experiences and attitudes toward suicide, and monitor their reactions to clients’ disclosures of suicidal ideation or behaviors (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005). It is important that disclosures be met with concern or care, as opposed to alarm or dismay (Joiner, 2005). One should conduct a careful self-assessment as to whether one can adequately treat high-risk clients, and it is recommended to maintain a list of other professionals available for consultation or referral (AAS, 2010; Rudd, 2006).

2. Develop and Maintain a Collaborative, Empathic Stance Toward the Client

In any therapeutic relationship, the clinician strives to establish rapport that will facilitate a lasting alliance; several sources suggest a collaborative alliance is particularly important when addressing issues of suicide with a client (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005; Rudd, 2006). An issue to be resolved when treating clients who experience suicidal ideation is the conflicting goals of the clinician to prevent suicide and the client to end psychological pain (AAS, 2010). Clinicians should maintain an empathic and collaborative approach to treatment. This can be achieved in part by using precise terminology when discussing suicide and never attempting to eliminate suicide as an option available to the client (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005; Rudd, 2006). Consistent with the notion of developing a collaborative stance is emergent empirical support for the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS; e.g., Ellis et al., 2012). The CAMS is a therapeutic assessment approach grounded in the importance of developing a therapeutic alliance with the client in order to: (a) clarify the key suicide risk and protective factors experienced by a client, and (b) collaboratively and transparently identify an intervention plan with the client (Ellis et al., 2012).

3. Know and Elicit Evidence-Based Risk and Protective Factors

One of the clinician’s primary objectives in conducting a suicide risk assessment is to elicit risk and protective factors from the client; thus, the clinician should possess some knowledge of evidence-based factors (AAS, 2010; Kleespies et al., 1993; Kleespies, Hough, & Romeo, 2009; Rudd, 2006; Sullivan & Bongar, 2009). There exists an extensive body of research regarding risk factors in the suicide literature. Although it would be impossible for clinicians to be familiar with every risk factor, some areas are of particular importance. Physical illness, such as HIV/AIDS and cancer, are correlated with higher suicide risk, especially when the illness is accompanied by depression (Kleespies et al., 2009; Kleespies et al., 1993; Bryan & Rudd, 2006). Other risk factors important to assess are experiences of loss, psychiatric diagnoses, previous attempts, thwarted belonging, perceived burdensomeness, and substance use (Joiner, 2005; Rudd, 2006; Sullivan & Bongar, 2009). Protective factors should not be ignored in the assessment of client risk. Factors such as social support, spiritual beliefs, and active involvement in a therapeutic relationship are among the most robust protective factors that can ameliorate risk (Rudd, 2006). At a minimum, it appears that a clinician should thoroughly assess psychiatric symptoms, environmental stressors, suicide ideation and attempts (inclusive of history and presence of intent, means, and lethality), loss, elements of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (Joiner, 2005), presence and use of social support, reasons for living, and faith.

4. Focus on Current Plan and Intent of Suicidal Ideation

When assessing a client’s risk, special attention should be given to the client’s immediate plan and intent (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005; Sullivan & Bongar, 2009;). The clinician should obtain detailed information regarding the frequency, intensity, and duration of the client’s suicidal ideation (AAS, 2010; Rudd, 2006; Sullivan & Bongar, 2009). The use of subjective ratings scales is one accepted method of doing so (Bryan & Rudd, 2006). In addition, the client’s access to means should be assessed, as well as any preparations for death that have been made, which would signal a more imminent risk (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005; Rudd, 2006). Reasonable efforts should be made to remove means of an attempt, with the exception where the clinician, client, or any other individual would be placed at risk for physical harm.

5. Determine Level of Risk

Many sources discuss the importance of making a determination of a client’s level of risk (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005; Rudd, 2006; Sullivan & Bonar, 2009). In addition to conducting a thorough bio-psychosocial interview and eliciting risk and protective factors, clinicians should attempt to obtain any available records or collateral information from other sources (e.g., family, friends, previous treatment provider), provided the client gives consent to do so (AAS, 2010). Psychodiagnostic testing (e.g., a personality inventory) may also be implemented as an additional means of assessing the client’s distress (Sullivan & Bongar, 2009). All available information should be integrated and analyzed so that the clinician can be as informed as possible before using their clinical judgment to determine the client’s level of risk (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005; Rudd, 2006; Sullivan & Bongar, 2009). Although several preferred terminologies exist to define risk level (cf. Bryan & Rudd, 2006; Van Orden et al., 2010), commonality among expert sources suggest attention to both chronic (i.e., long-term) and acute (i.e., imminent) risk levels. Use of phraseology such as low, moderate, high, and extreme risk is preferred over mere statements of absent/present.

6. Develop and Enact a Collaborative Evidence-Based Treatment Plan

After a determination of risk is made, the clinician and client can then collaborate and design an emergency plan that aims to keep the client safe (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005; Rudd, 2006; Sullivan & Bongar, 2009). The plan should address the immediate suicidal ideation or behavior, implement interventions in session to alleviate distress, and include the monitoring of risk level (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005). It is important to note that suicide risk is dynamic and can fluctuate depending on the constellation of risk and protective factors present (Joiner, 2005; Rudd, 2006). As such, emergency or crisis response plans can also include coping skills for use beyond session, identification of safe persons and environments, written statements of reminders of reasons for living, and a list of all necessary emergency contact phone numbers.

7. Notify and Involve Other Persons

Assessment and treatment of suicidal behaviors is not an endeavor for the clinician and client alone (AAS, 2010; Rudd, 2006; Sullivan & Bongar, 2009). In short, social support for the client can be conceptualized as a broad idea, inclusive of many persons. For example, it is recommended that the clinician obtain the client’s consent to notify other treatment providers and members of the client’s social network (AAS, 2010; Sullivan & Bongar, 2009). Granted, the clinician should also note that there are instances of high imminent risk where consent is unnecessary. In any case, working with other providers allows for an interdisciplinary approach to treatment, particularly when psychopharmacological treatment or hospitalization is necessary. Notification of the client’s friends and family serves to begin establishing a support network that will be available to the client throughout treatment (Sullivan & Bongar, 2009). In doing so, the clinician can work with the client to involve the most trusted persons in his or her life; this may include extended family, church community members, social or extracurricular activity group members, mentors, and others beyond a romantic partner or parent/sibling.

8. Document Risk, Plan, and Reasoning for Clinical Decisions

A common theme noted in several sources was the importance of documentation, both for the purposes of professional liability and as a means of monitoring the client’s risk and treatment progress (AAS, 2010; Rudd, 2006). Beginning with the informed consent process, detailed documentation of information related to risk and rationales for treatment should be maintained (AAS, 2010; Rudd, 2006). Direct quotations from the client and copies of any safety plan should be included in the documentation (Rudd, 2006). Additionally, any contact with colleagues regarding the case should be documented, as well as the progress and outcome of assessment and treatment (AAS, 2010; Rudd, 2006). In addition to these topics of documentation, minimal standards of documentation include the most prominent risk and protective factors obtained in the suicide risk assessment interview, identification and rationale for the assigned risk level, and immediate and long-term actions taken as a result of the risk level decision.

9. Know the Law Concerning Suicide

Several sources address the importance of familiarity with laws concerning suicide (AAS, 2010; Joiner, 2005; Rudd, 2006). Laws regarding suicide (e.g., criteria and process for involuntary civil commitment and breaches of confidentiality) vary by state (AAS, 2010). Clinicians should familiarize themselves with the laws in their particular jurisdictions in order to expedite the commitment process should it be necessary. In addition to legal statutes, clinicians should also know the standards of care and ethical obligations pertaining to the assessment and treatment of suicidality, as legal action could result from failure to meet the professional and ethical standards (Joiner, 2005). Knowledge of the legal statutes and ethical responsibilities should provide additional guidance and structure for documentation (AAS, 2010; Rudd, 2006).

10. Engage in Debriefing and Self-Care

Self-care of the clinician involved in treatment of a suicidal client is perhaps an underserved area in the research literature, and was only addressed by three sources (Joiner, 2005; Kleespies et al., 2009; Kleespies et al., 1993). Conducting a suicide risk assessment or being involved in the treatment of a client in a suicidal crisis can be a stressful event for clinicians regardless of their level of clinical experience. Feelings of guilt, incompetence, and concern regarding possible mistakes made in the assessment process commonly occur following a client’s suicide attempt or completion (Webb, 2011). Self-care becomes an integral part of treatment with high risk clients to ensure that the clinician is mentally and emotionally available. Although feeling a sense of responsibility for a client’s well-being is understandable, Joiner (2005) suggests clinicians remain mindful of a healthy level of emotional distance regarding such difficult client situations. As such, clinicians are encouraged to utilize their social network for support, as well as consult with colleagues who have had similar experiences (Kleespies et al., 2009; Kleespies et al., 1993).

A Framework for Suicide Risk Assessment Training in Clinical Psychology Programs

Currently, the most common form of suicide risk assessment training in psychiatry is in the form of grand rounds and case conferences (Melton & Coverdale, 2009), with other methods employed as mentioned above. Data continually suggest that these methods are inadequate from the perspective of participants (e.g., Melton & Coverdale, 2009; Palmieri et al., 2008). Precedent exists for the advice to utilize interactive training methods such as role plays as well (see Rudd et al., 2008). A more integrative emergent training tool used in other domains of psychiatric (e.g., Hubbeling, 2010; McNiel, Hung, Cramer, Hall, & Binder, 2011; Whelan, Church, & Kadry, 2009) and nursing (e.g., Holland et al., 2010; Walsh, Bailey, & Koren, 2009) training is the Objective Structured Clinical Evaluation or Examination (OSCE).

The basic goal of an OSCE is to demonstrate competency in a given domain of training (Watson, Stimpson, Topping, & Porock, 2002). Traditionally, expert raters provide dichotomous ratings of the trainee’s performance (Miller, 2010). Procedures of an OSCE may vary, but generally feature trainee engagement with a standardized patient or actor who operates from a preestablished patient script (Miller, 2010). The OSCE possesses several benefits, including high face validity as a training tool that may encourage further trainee preparation (Rudland, Wilkinson, Smith-Han, & Thompson-Fawcett, 2008). Moreover, existing data support good training validity and effectiveness of OSCE methods (e.g., Martin & Jolly, 2002; McNiel et al., 2011; Varkey, Natt, Lesnick, Downing, & Yudkowsky, 2008).

To date no studies exist applying an OSCE to clinical psychology training. McNiel and his team of researchers (Hung et al., 2012; McNiel et al., 2011) demonstrate a sound exemplar of how an OSCE can be utilized for suicide and violence risk assessment in the context a psychiatry training program. Prior to the training, researchers developed a competency rating form based on a literature review and established violence risk assessment standards. Moreover, they obtained feedback on the form in focus groups. Researchers then assembled a training curriculum addressing each of the competency domains on the rating form. Learners, or trainees, then engaged in the following stepwise process: (a) underwent the workshop on suicide and violence risk assessment and management in group presentation format, (b) conducted a videotaped risk assessments of a mock standardized patient, (c) received expert ratings on these assessments, and (d) completed pre- and posttest measures of confidence, knowledge, and mock progress notes. Competency assessment instruments of trainee skill mastery were formulated to provide expert raters with a way to rate trainee performance. For example Hung et al. (2012) created and tested the Competency Assessment Instrument-Suicide (CAI-S), which includes 29 domain-specific competencies to master (each rates on a 4-point scale), as well as an overall rating of trainee competence on an 8-point scale (see Hung et al., 2012; McNiel et al., 2011 for further details). It should be noted that interrater reliability was established in the process of experts rating trainee competence. Notably, trainees did not complete self-report versions of these measures for comparison of consistency in self- and observer-perceptions of trainee competence. Such data would prove informative for the overall effectiveness of the OSCE.

At present, there exists potential utility of an integrated framework combining OSCE application and competency rating form development in the context of psychology training programs. As such, we propose a model combining elements of McNiel and colleagues’ methodology, current evidence-based teaching of psychology methods, and an assessment instrument featuring self- and observer-ratings of the core competencies articulated earlier. To our knowledge, no psychology doctoral or internship training programs have adopted such a training module. Although admittedly cost and time intensive, the potential benefit with regard to clinician competency/skill development in a life/death area of clinical practice is perhaps immeasurable. Moreover, psychiatry training programs feature such methodologies as a gold standard for skill development (see review above). Psychology training programs could benefit from following suit in this regard given the lack of known effectiveness of mere classroom or lecture style suicide risk assessment training. We acknowledge that not every training program is so well prepared; overall, training programs could adapt the proposed method outlined below to best meet training needs while balancing infrastructure and time limitations.

In an OSCE/Rating form training program, clinical or counseling psychology trainees would receive an extensive workshop guided by the 10 core competencies. Evidence-based teaching and training techniques should be utilized above and beyond mere psychoeducation. For instance, role playing of specific skills, expert demonstrations, sample progress note documentation, and peer-to-peer pair and group discussions of each core competency can easily be integrated into an interactive workshop. Prior to the workshop, trainees would complete self-perceptions of his or her abilities/competencies, knowledge, and opinions, as well as a mock progress note of risk level of a case vignette. After undergoing the workshop, each trainee will conduct a videotaped risk assessment on a standardized client. Following this, each trainee would complete post self-ratings on the same measure to evaluate self-perceived gains in competence. Expert raters would subsequently rate the videotaped scenario on the 10 core competences and provide the trainee feedback. Again, this methodology is consistent with that of McNiel and colleagues approach (Hung et al., 2012; McNiel et al., 2011).

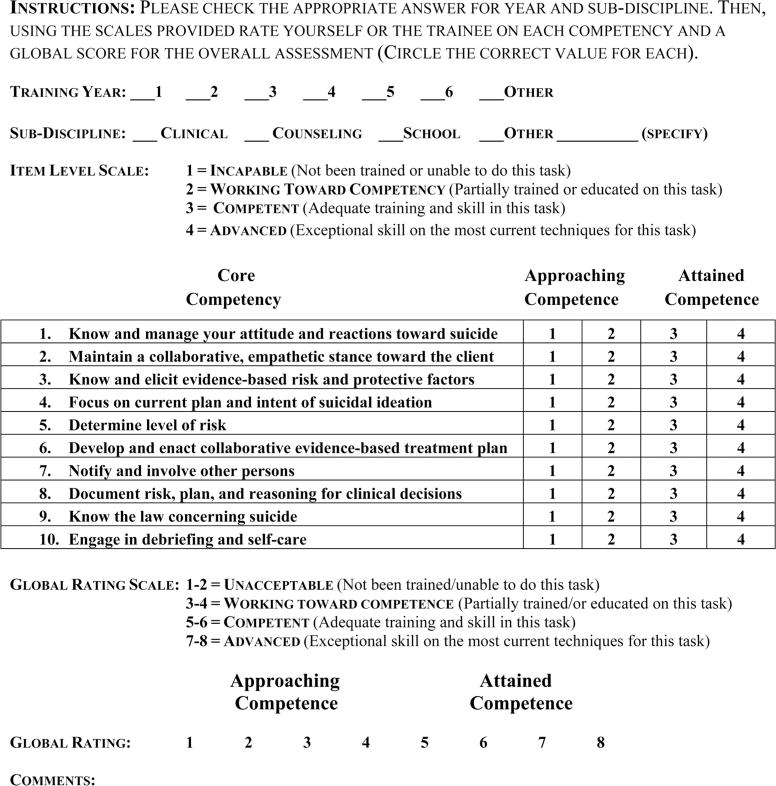

As an adjunct to this training modality, we propose a Suicide Competency Assessment Form (SCAF; see Appendix) based on the 10 core competencies in this article. Although tools for evaluating competency have been developed (e.g., Hung et al., 2012; King et al., 2006), they suffer from limitations. The sheer number of competencies (39 and 29, respectively) contained on each makes feedback for the trainee potentially overwhelming. Moreover, there is a high degree of disagreement between the measures. Thus, the shorter core competency measure we composed includes elements of both of these instruments in a succinct and practical manner for research and training purposes. Additionally, the SCAF retains the basic format and valuable components of the CAI-S (Hung et al., 2012), namely the ratings scales/labels, an overall global rating, and an open-ended “comments” section. We recommend use of these aspects to spur qualitative thematic supervisory feedback and discussion with the trainee.

Where full OSCE methods are cost or time prohibitive, alternative uses of the SCAF are feasible, as training programs may implement the SCAF within existing academic courses, seminars, or didactics. For example, authors of the present article, McNiel and colleagues group, and others, have developed intensive focus group or workshops for trainees. To the extent that the content of these training programs matches the SCAF, workshop participants can complete the SCAF in prepost designs, and utilize the content as a source of interactive discussion. In a more traditional classroom setting, small practicum courses may also make use of the SCAF as a guide to stepwise training for doctoral students for in-class exercises addressing core competencies. Such didactic or classroom exercises can include critiquing mock risk assessment documentation, use of established training videos in the field (e.g., those by the Glendon Association, n.d.), and small group-level mock suicide risk interviews in which the instructor is a mock client. Also, insofar as many training sites are equipped with technology-ready training clinics, videotaping of standardized patient sessions would be well facilitated.

Limitations and Conclusions

These guidelines for a clinical or counseling psychology training model can be adapted as necessary. What appears of most import is beginning efforts for research on and application of an evidence-based, standardized method of suicide risk assessment training in clinical and counseling psychology programs. Indeed, we must acknowledge the lack of empirical data demonstrating OSCE effectiveness and adequate psychometric properties of the SCAF in the context of suicide risk assessment training. This seems a valuable next step in enhancing suicide risk assessment training science. Also, the present discussion, inclusive of literature review, competency development, and proposed training method, is limited to doctoral psychology training programs. Other domains of practicing psychology (e.g., school, health) may possess domain-specific competencies not covered in the present investigation.

Biographies

Robert J. Cramer, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Sam Houston State University. He obtained his doctorate in clinical psychology from the University of Alabama. His research interests include LGBT issues, hate crimes, suicide risk assessment, and trial consulting.

Shara M. Johnson, MA is a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology at Sam Houston State University where she also obtained her master’s in clinical psychology. Her research interests include physician assisted suicide, suicide risk assessment, and forensic assessment.

Jennifer McLaughlin, MA is a doctoral student in clinical psychology at Sam Houston State University where she also obtained her master’s in clinical psychology. Her research interests include forensic assessment, assessment of malingering, and multicultural issues.

Emilie M. Rausch, BA is a graduate research trainee in quantitative psychology at the University of Missouri. She received her bachelor’s in psychology from the University of Missouri. Her research interests are mixture modeling, cluster analysis, and social network analysis.

Mary Alice Conroy, PhD is a professor of psychology at Sam Houston State University. She obtained her PhD from the University of Houston. Her research interests include forensic assessment and training competencies.

Appendix. Suicide Competency Assessment Form (SCAF)

Figure 1a.

Contact authors directly for a ready-to-use electronic version of the SCAF.

Contributor Information

Robert J. Cramer, Sam Houston State University

Shara M. Johnson, Sam Houston State University

Jennifer McLaughlin, Sam Houston State University.

Emilie M. Rausch, University of Missouri

Mary Alice Conroy, Sam Houston State University.

References

- American Association of Suicidology. Some facts about suicide and depression. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.suicidology.org/c/document_library/get_file?folderId=232&name=DLFE-246.pdf.

- Appleby L, Morriss RR, Gask LL, Roland MM, Lewis BB, Perry AA, Faragher BB. An educational intervention for front-line health professionals in the assessment and management of suicide patients (The STORM Project) Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences. 2000;30:805–812. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799002494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belar CD. Advancing the culture of competence. Training and Education in Professional Psychology. 2009;3:S63–S65. doi: 10.1037/a0017541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bongar B, Harmatz M. Clinical psychology graduate education in the study of suicide: Availability, resources, and importance. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1991;21:231–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan C, Rudd M. Advances in the assessment of suicide risk. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:185–200. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter-Mazza E, Freeman K. Graduate training and the treatment of suicidal clients: The students’ perspective. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2003;33:211–218. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.2.211.22769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis TE, Dickey T. Procedures surrounding the suicide of a trainee’s patient: A national survey of psychology internships and psychiatry residency programs. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1998;29:492–497. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.29.5.492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis TE, Green KL, Allen JG, Jobes DA, Nadoff MR. Collaborative assessment and management of suicidality in an inpatient setting: Results of a pilot study. Psychotherapy. 2012;49:72–80. doi: 10.1037/a0026746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick CD, Vassilas CA, Carter H, Haque MS. Training health professionals in the recognition, assessment and management of suicide risk. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2004;8:117–121. doi: 10.1080/13651500410005658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendon Association. Voices of suicide: Learning from those who lived [DVD] n.d Retrieved from http://www.psychotherapy.net/video/suicide-glendon.

- Holland K, Roxburgh M, Johnson M, Topping K, Waston R, Lauder W, Porter M. Fitness for practice in nursing and midwifery education in Scotland, United Kingdom. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19:461–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: Preliminary data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2011;61:1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbeling DAA. The role of OSCEs in post-graduate psychiatry assessments. Academic Psychiatry. 2010;34:455–456. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.34.6.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung EK, Binder RL, Fordwood SR, Hall SE, Cramer RJ, McNiel DE. A method for evaluating competency in assessment and management of suicide risk. Academic Psychiatry. 2012;36:23–28. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.10110160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kenkel MB, Peterson RL. Competency-based education in professional psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- King R, Lloyd C, Meehan T, O’Neill K, Wilesmith C. Development and evaluation of the Clinician Suicide Risk Assessment Checklist. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health. 2006;5(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kleespies PM. The stress of patient suicidal behavior: Implications for interns and training programs in psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1993;24:477–482. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.24.4.477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleespies PM, Hough S, Romeo AM. Suicide risk in people with medical and terminal illness. In: Kleespies PM, editor. Behavioral emergencies: An evidence-based resource for evaluating and managing risk of suicide, violence, and victimization. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kleespies PM, Penk W, Forsyth J. The stress of patient suicidal behavior during clinical training: Incidence, impact, and recovery. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1993;24:293–303. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.24.3.293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleespies PM, Smith MR, Becker BR. Psychology interns as patient suicide survivors: Incidence, impact, and recovery. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1990;21:257–263. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.21.4.257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin IG, Jolly B. Predictive validity and estimated cut score of an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) used as an assessment of clinical skills at the end of the first clinical year. Medical Education. 2002;36:418–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNiel DE, Fordwood S, Weaver C, Chamberlain J, Hall S, Binder R. Effects of training on suicide risk assessment. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:1462–1465. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNiel DE, Hung EK, Cramer RJ, Hall SE, Binder RL. An approach to evaluating competency in assessment and management of violence risk. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:90–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton BB, Coverdale JH. What do we teach psychiatric residents about suicide? A national survey of chief residents. Academic Psychiatry. 2009;33:47–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.33.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JK. Competency-based training: Objective structured clinical exercises (OSCE) in marriage and family therapy. Journal of Marriage and Family Therapy. 2010;36:320–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morriss R, Gask L, Battersby L, Francheschini A, Robson M. Teaching front-line health and voluntary workers to assess and manage suicidal patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1999;52:77–83. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oordt M, Jobes D, Fonseca V, Schmidt S. Training mental health professionals to assess and manage suicidal behavior: Can provider confidence and practice behaviors be altered? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2009;39:21–32. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri G, Forghieri M, Ferrari S, Pingani L, Coppola P, Colombini N, Neimeyer RA. Suicide intervention skills in health professionals: A multidisciplinary comparison. Archives of Suicide Research. 2008;12:232–237. doi: 10.1080/13811110802101047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Cross W, Gould M. The assessment and management of suicide risk: State of workshop education. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2011;41:255–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves A, Wheeler S, Bowl R. Assessing risk: Confrontation or avoidance–What is taught on counsellor training courses. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 2004;32:235–247. doi: 10.1080/03069880410001697288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD. Assessment and management of suicidality. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Cukrowicz KC, Bryan CJ. Core competencies in suicide risk assessment and management: Implications for supervision. Training and Education in Professional Psychology. 2008;2:219–228. doi: 10.1037/1931-3918.2.4.219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudland J, Wilkinson T, Smith-Han K, Thompson-Fawcett M. You can do it late at night or in the morning. You can do it at home, I did it with my flatmate”. The educational impact of an OSCE. Medical Teacher. 2008;30:206–211. doi: 10.1080/01421590701851312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutz W, von Knorring L, Walinder J. Frequency of suicide on Gotland after systematic postgraduate education of general practitioners. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1989;80:151–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb01318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz W, Jr, Allen M, Feldman B, Gutin N, Jahn D, Kleespies P, Simpson S. Preventing suicide through improved training in suicide risk assessment and care. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2012;42:292–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan GR, Bongar B. Assessing suicide risk in the adult patient. In: Kleespies PM, editor. Behavioral emergencies: An evidence-based resource for evaluating and managing risk of suicide, violence, and victimization. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Szanto K, Kalmar S, Hendin H, Rihmer Z, Mann J. A suicide prevention program in a region with a very high suicide rate. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:914–920. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite RS, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varkey P, Natt N, Lesnick T, Downing S, Yudkowsky R. Validity evidence for an OSCE to assess competency in systems-based practice and practice-based learning and improvement: A preliminary investigation. Academic Medicine. 2008;83:775–780. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31817ec873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh M, Bailey PH, Koren I. Objective structured clinical evaluation of clinical competence: An integrative review. Journal of Advancing Nursing. 2009;65:1584–1595. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson R, Stimpson A, Topping A, Porock D. Clinical competence assessment in nursing: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;39:421–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb KB. Care of others and self: A suicidal patient’s impact on the psychologist. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2011;42:215–221. doi: 10.1037/a0022752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan P, Church L, Kadry K. Using standardized patients’ marks in scoring postgraduate psychiatry OSCEs. Academic Psychiatry. 2009;33:319–322. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.33.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]