Abstract

Genital Alphapapillomavirus (αPV) infections are one of the most common sexually transmitted human infections worldwide. Women infected with the highly oncogenic genital human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18 are at high risk for development of cervical cancer. Related oncogenic αPVs exist in rhesus and cynomolgus macaques. Here the authors identified 3 novel genital αPV types (PhPV1, PhPV2, PhPV3) by PCR in cervical samples from 6 of 15 (40%) wild-caught female Kenyan olive baboons (Papio hamadryas anubis). Eleven baboons had koilocytes in the cervix and vagina. Three baboons had dysplastic proliferative changes consistent with cervical squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). In 2 baboons with PCR-confirmed PhPV1, 1 had moderate (CIN2, n = 1) and 1 had low-grade (CIN1, n = 1) dysplasia. In 2 baboons with PCR-confirmed PhPV2, 1 had low-grade (CIN1, n = 1) dysplasia and the other had only koilocytes. Two baboons with PCR-confirmed PhPV3 had koilocytes only. PhPV1 and PhPV2 were closely related to oncogenic macaque and human αPVs. These findings suggest that αPV-infected baboons may be useful animal models for the pathogenesis, treatment, and prophylaxis of genital αPV neoplasia. Additionally, this discovery suggests that genital αPVs with oncogenic potential may infect a wider spectrum of non-human primate species than previously thought.

Keywords: alphapapillomavirus, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, oncology, papio, PCR, primate, reproductive, viral

Papillomaviruses (PVs) are a highly diverse group of double-stranded DNA viruses that infect either skin or mucosal surfaces.1,3,5,18 In some cases infection may be clinically inapparent, however PVs are also known to induce proliferative changes ranging from benign neoplasms (papillomas) to malignancies (carcinomas). PVs are classified into genera and types based on the sequence of the capsid L1 gene.3 The genus Alphapapillomavirus (αPV) is medically significant in that it contains the oncogenic genital PV types associated with virtually all cases of human cervical cancer and a subset of anal, penile, and head and neck carcinomas.4,19,23,34 Precancerous human papillomavirus (HPV)–associated genital lesions in women typically present as cervical or vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN/VaIN) that may progress to invasive carcinoma.34 Cutaneous and benign mucosal PV infections have been identified in a wide variety of animal species.18 Recently, PV infection has been identified in squamous cell carcinomas of the male genitals in horses.16 In contrast, CIN/VaIN-associated αPVs have only been reported in humans and in macaques (Macaca spp.).8,9,22,32,33 The morphology and progression of these lesions in macaques correlates well with human genital αPV infections, and CIN-associated macaque αPVs are closely related phylogenetically to oncogenic genital HPVs.5,7,9

Here we describe 3 novel types of genital αPV infection identified in wild-caught female Kenyan olive baboons (Papio hamadryas anubis). Some virally infected baboons had either moderate (grade II CIN, n = 1) or mild (grade I CIN, n = 2) cervical dysplasia. This was an unexpected and potentially confounding finding emerging from an experimental study of Chlamydia trachomatis–induced pelvic inflammatory disease.2 To our knowledge, genital PV infection or CIN-type changes have not been described in the baboon.

Materials and Methods

Animal Background

The 18 adult female wild-caught Kenyan olive baboons (Papio hamadryas anubis) were in an experimental study of cervical Chlamydia trachomatis infection as a model for pelvic inflammatory disease.2 Animals were captured using baited traps and transported to the Institute for Primate Research (IPR) in Nairobi, Kenya. Animals were trapped as entire troops from areas in which they had been reported as a nuisance. Trapping and use were under an authorized permit from the Kenyan Wildlife Service in accordance with the Convention for International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Institute for Primate Research, which is a World Health Organization Collaborating Centre that utilizes animal use guidelines modeled after the Primate Vaccine Evaluation Network, the Council for the International Organizations of Medical Sciences (a World Health Organization working group), and the National Institutes of Health Public Health Service policies.

The baboons underwent a 12-week quarantine and conditioning period prior to cervical inoculation with C. trachomatis. Animals were evaluated by physical examination under ketamine sedation (Ketaset, 10 mg/kg, IM) to screen out those with abnormal cervicovaginal discharge or gross abnormalities. Four baboons served as controls and 14 were cervically inoculated with 1 ml of a 1 × 107 IFU/mL of C. trachomatis either once (n = 8) or 5 times at weekly intervals (n = 6). Details of the C. trachomatis study have been described previously.2

Euthanasia, Necropsy, and Histology

At the end of the 16-week study period, the baboons were humanely euthanized by intravenous injection with 60 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (Euthanaze®, CENTAUR LABS, Johannesburg, South Africa) and were necropsied for harvest and evaluation of the reproductive tract. The reproductive tracts were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 to 72 hours and were processed through graded alcohols and toluene to wax by routine histological methods. Paraffin blocks were shipped to the University of Michigan and hematoxylin-and-eosin stained sections of vagina, cervix, uterus, oviducts, and ovaries were prepared. Gram and PAS stains were generated by routine histological methods.25

Histological Grading of CIN Lesions

Histological sections were evaluated by a board-certified veterinary pathologist (ILB) blinded to the experimental groups. CIN lesions were classified according to the degree of basal epithelial expansion and histological atypia, using criteria derived from human gynecological pathology.34 These criteria were previously applied to αPV-induced cervicovaginal changes in macaques.10,31,33 Specifically, CIN3 was defined as basal epithelial expansion greater than two-thirds the height of the mucosa, accompanied by large, atypical keratinocytes. Keratinocyte atypia was defined as karyomegaly and hyperchromatic nuclei. CIN2 was defined as basal epithelial expansion between one-third and two-thirds the height of the mucosa and the presence of atypical keratinocytes. CIN1 was defined by basal epithelial expansion < one-third the height of the mucosa and few, if any atypical keratinocytes. In keeping with currently accepted criteria in human medical pathology, a CIN1 lesion was considered consistent with PV infection but not pre-malignancy, CIN2 was considered moderate dysplasia, and CIN3 lesions were considered high-grade with malignant potential.34

Immunohistochemistry

Immunolabeling was performed on paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed cervical tissues using commercially available primary monoclonal antibodies for Ki67 (Ki67-MIB1, Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA).33 The primary antibody was diluted 1:50 in Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.5% casein as a blocking reagent. Incubation was performed overnight at 4°C. The immunolabeling protocol consisted of heat-induced antigen-retrieval with citrate buffer (pH 6.0), biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse Fc antibody as a linking reagent, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin as the label, hematoxylin as the counterstain, and Vector Red as the chromagen (BioGenex, Burlingame, CA). All immunolabeling batches included positive control slides (macaque tissue with high levels of Ki67 labeling) and negative staining control slides (species-matched non-immune serum in place of the primary antibody).

Chlamydia Trachomatis Detection

C. trachomatis cultures were performed by the clinical Microbiology laboratory at the University of Michigan and PCR was performed by the Chlamydia detection laboratory at the University of Washington as previously described.2

Papiine Herpesvirus 2 Screening

PCR testing for Papiine herpesvirus 2 was performed by a commercial laboratory (Zoologix; using unfixed cervical tissue samples that had been maintained at −70°C in RNAlater (Ambion).

PCR and DNA Sequencing

Cervical tissue samples taken at necropsy from 15 animals were placed in RNAlater (Ambion), frozen at −70°C, and shipped under controlled cold storage conditions (dry ice). Total DNA was partially purified from the cervical samples and was amplified using Ampli Taq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with MY09/11, GP5+/6+, and FAP primer sets targeting conserved regions within the L1 gene.6,7,12 Only MY09/11 primers showed positive results for some cervical samples. PCR-positive samples had the amplified DNA fragments purified and sequenced at the Einstein Genomics Core facility. Sequences from the PCR products were compared with known PV types from the NCBI GenBank database and the Burk lab database using a BLAST searching algorithm. Viruses with sequences less than 90% homologous to previously typed αPVs were further characterized. One isolate was completely cloned and sequenced and named PhPV1 (P.hamadryas PV) based on the host from which the virus was isolated as described.3 Two isolates, PhPV2 and PhPV3, were partially sequenced and classified based on the MY-L1 region sequences.

Papio Hamadryas Papillomavirus 1 (PhPV1) Genome Cloning and Sequencing

Type-specific primer sets were designed based on available sequences including a consensus region within the E1 open reading frame (ORF) to allow amplification of the complete genome of PhPV1 in 2 overlapping fragments (2876 bp and 5571 bp).28,29 Oligonucleotide primer sequences are available from the authors (RDB). For overlapping PCR, an equal mixture of the AmpliTaq Gold Taq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems) and Pwo Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (High Fidelity, Invitrogen, USA) were utilized as previously described.28 PCR products of appropriate size were cloned into the TOPO TA pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and sequenced in the Einstein Genome Facility, New York. Subsequent sequencing was performed using primer walking. The complete genome sequence of PhPV1 was compiled from the sequences of overlapping cloned fragments and submitted to NCBI/GenBank (accession number: JF304764). The MY-L1 sequences of PhPV2 and PhPV3 were also submitted (accession numbers JQ041819 and JQ041820, respectively).

Phylogenetic Analysis and Tree Construction

The complete L1 ORF nucleotide sequences of representative αPVs were used to evaluate the phylogenetic positions of the 3 baboon papillomaviruses. The MY-L1 nucleotide sequences were applied if the complete L1 ORFs were unavailable for some non-human primate (NHP) PVs. The amino acids of L1 ORF were aligned using MUSCLE v3.7 within the Seaview v4.1 program; the nucleotide sequences were then aligned using the corresponding aligned amino acid sequences. A maximum likelihood tree was constructed using RAxML MPI v7.2.8.27 The GTR + gamma model was set for among-site rate variation and allowed substitution rates of aligned sequence to be different.

Results

Histological Findings

Vaginal and cervical tissues of 18 wild-caught Kenyan olive baboons were histologically evaluated as part of an experimental study of C. trachomatis-associated pelvic inflammatory disease. In 11 of 18 animals (61%) there were unexpected koilocytic changes (perinuclear clearing with shrunken nuclei) multifocally or diffusely within the stratum spinosum of the exocervix, close to the transformation zone (Table 1). Three animals (16.7%) had proliferative changes consistent with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions. Lesions were located in the exocervical epithelium in close proximity to the transformation zone. Specifically, these animals had localized or multifocal thickening and irregularity of the basal epithelium with varying degrees of atypia. Baboon 1 had a lesion classified as CIN2 based on the presence of basal epithelial expansion between one-third and two-thirds of the mucosal height and the presence of numerous hyperchromatic, karyomegalic cells (Figs. 1, 2). Baboon Nos. 2 and 3 had lesions consisting of basal epithelial expansion affecting < one-third mucosal height with koilocytes and cytomegaly but lacking the atypia seen in baboon No. 1. These lesions were classified as CIN1 (low grade) (Figs. 3, 4). Suprabasilar mitotic figures were rare and inclusion bodies were not observed. Hyperkeratosis, usually parakeratosis, was often observed in exocervical epithelium in close proximity to the squamocolumnar transformation zone (Fig. 5). This finding was also present in baboons without cervical dysplasia.

Table 1.

Histological Findings in Baboons Correlated With PCR Results and Capture Sites.

| Animal ID | Lymphocytic cervicovaginal inflammationa | Koilocytesb | Dysplasia (CIN grades 1, 2, 3)c | PCR resultd | Capture sitee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 2 | CIN2 | PhPV1 | A1 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | CIN1 | PhPV2 | A1 |

| 3 | 3 | 1 | CIN1 | PhPV1variant | A2 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | PhPV3 | B1 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | PhPV2 | A1 |

| 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | PhPV3 | B1 |

| 7 | 4 | 1 | 0 | neg | A2 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | neg | A2 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | neg | B1 |

| 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | neg | A1 |

| 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | neg | A1 |

| 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | neg | A1 |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | neg | A1 |

| 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | neg | C1 |

| 15 | 1 | 1 | 0 | neg | A3 |

| 16 | 4 | 1 | 0 | na | C1 |

| 17 | 2 | 1 | 0 | na | A1 |

| 18 | 1 | 0 | 0 | na | A1 |

Inflammation graded as 0: none, 1: mild, 2: moderate, 3: marked, 4: severe.

Koilocytes graded as 0: not evident, 1: occasional, 2: moderate, 3: marked, 4: severe.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grading criteria described in text. CIN1: low grade, CIN2: moderate dysplasia, CIN3: high grade.

Alphapapillomavirus species identified from cervical samples. Neg, no amplicon; na, not tested (unfixed cervical sample not available).

Capture sites in Kenya. Letter indicates district. Numbers indicate capture sites within district. A1: Kajiado district, Ngurumani Daraja; A2: Kajiado district, Ngurumani Oloorbototo; A3: Kajiado district, Ngurumani point A; B1: Machakos district, Yatta; C1: Laikipia district, Lamuria Aberdares.

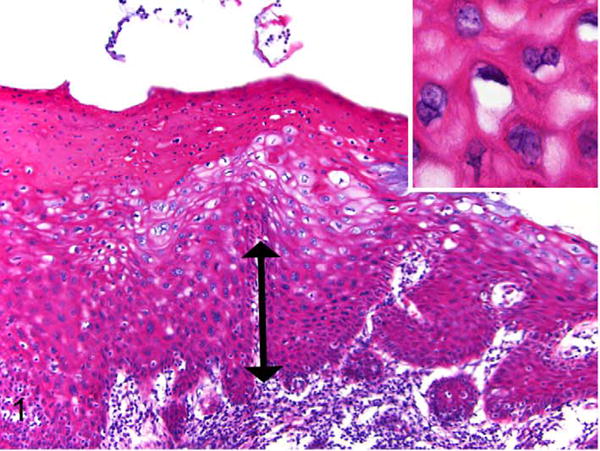

Figure 1.

Exocervix, baboon No. 1. Squamous intraepithelial lesion assessed as moderate cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2). There is basal epithelial expansion (double arrow) affecting one-third to two-thirds of the mucosa. Koilocytes (epithelial cells with perinuclear halos and shrunken nuclei) and binucleated keratinocytes are present (inset). There is parakeratosis of the superficial epithelium, a feature commonly noted in baboons in this study. HE.

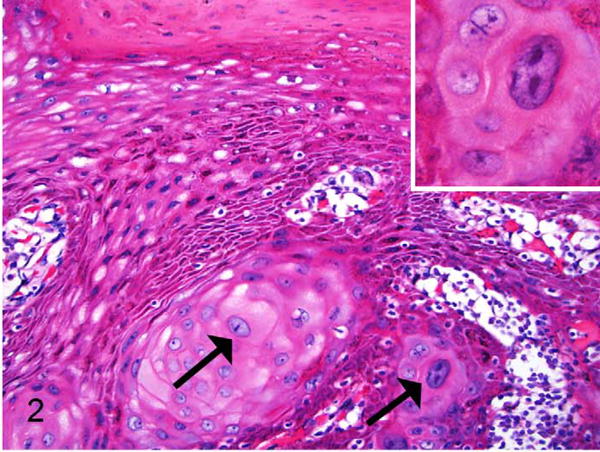

Figure 2.

Exocervix, baboon No. 1. Squamous intraepithelial lesion from the same animal as in Figure 1, taken from a different exocervical site within the same section and also assessed as moderate dysplasia (CIN2). In addition to the basal epithelial expansion there is disorderly keratinocyte maturation with several large, hyperchromatic, and atypical cervical keratinocytes (arrows). Many are karyomegalic and there are frequent binucleated cells (inset). HE.

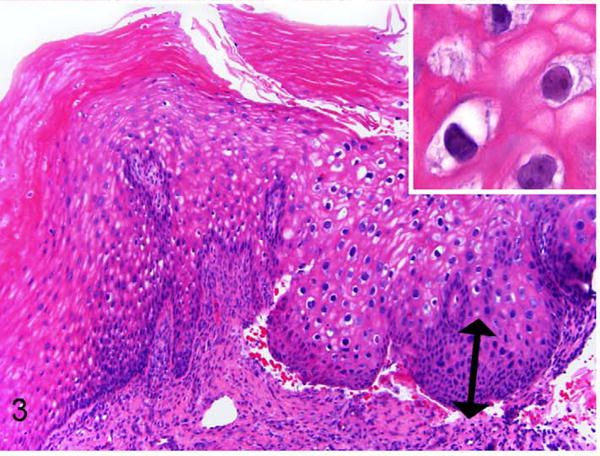

Figure 3.

Exocervix, baboon No. 2. Area of epithelial hyperplasia and atypia assessed as CIN1 (low-grade). Basal epithelial expansion affects approximately one-third mucosal height (double arrow). This animal does not have the degree of atypia as in baboon No. 1, but there are koilocytes and individual karyomegalic cells present within the stratum spinosum (inset). HE.

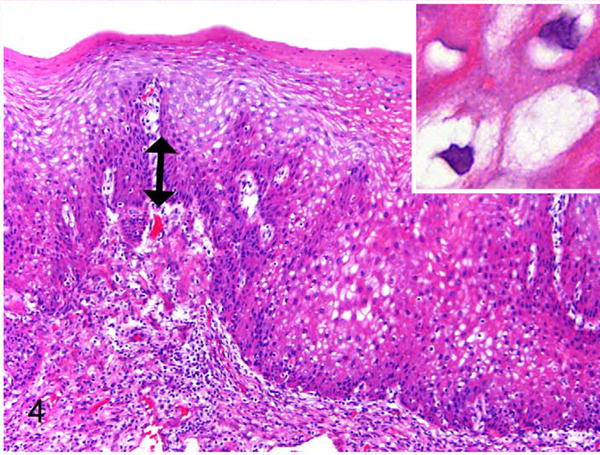

Figure 4.

Exocervix, baboon No. 3. Area of epithelial hyperplasia assessed as CIN1 (low-grade). Basal epithelial expansion affects < one-third mucosal height (double arrow). Normal polarity and maturation are maintained. There are numerous koilocytes (inset) with enlarged cells but minimal atypia (inset). HE.

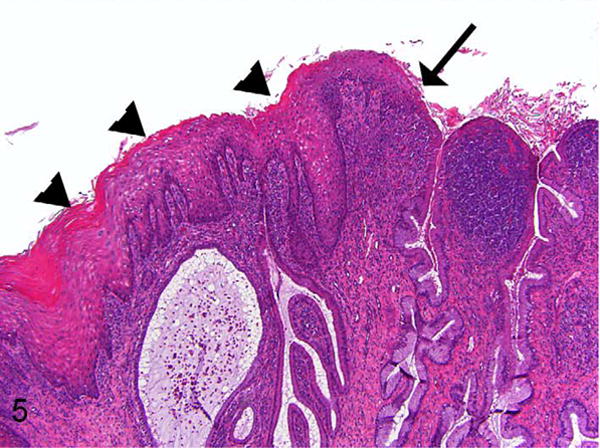

Figure 5.

Lower magnification of exocervix and squamocolumnar junction, baboon No. 2. This illustrates the proximity of parakeratotic cervical epithelium (arrowheads) to the squamocolumnar junction (arrow). This section is a recut from a deeper level of the block than what is shown in Figure 3. Parakeratosis of varying degrees was frequently observed at or near the squamocolumnar junction in multiple animals in the study. This figure also illustrates the cervical inflammation (predominantly lymphoplasmacytic) that was frequently present in the animals in this study. HE.

Immunohistochemistry for Ki67

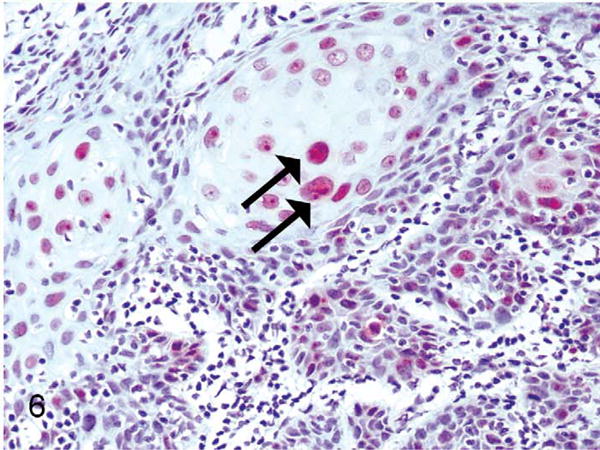

Although not previously reported in the baboon, the histological findings were suggestive of genital αPV infection. As an additional evaluation, immunohistochemical labeling for the proliferation marker Ki67 was performed on 9 animals with histological evidence of CIN lesions or increased koilocytes. Prior studies have shown that increased suprabasilar labeling of Ki67 correlates with HPV-associated cervical dysplasia.19,33 There was altered Ki67 labeling in baboon No. 1, consisting of moderately expanded suprabasilar Ki67 labeling within a CIN2 lesion (Fig. 6). Baboon No. 2 had no alteration in Ki67 within CIN1 lesions. Baboon No. 3 had mild multifocal suprabasilar Ki67 labeling (not shown). Additionally, baboon No. 4, which had widespread koilocytosis but lacked histologically evident dysplasia, had diffuse basilar and suprabasilar Ki67 labeling. The remaining animals had Ki67 labeling confined to the basilar layer (normal).

Figure 6.

Exocervix, baboon No. 1. Suprabasilar nuclear immunostaining for the proliferation marker Ki67 (MIB1) (arrows) within a CIN2 lesion associated with PhPV1 infection.

Identification of Papillomaviral Sequence

Based on the histological evidence, PCR identification of potential αPV was pursued. Consensus PCR primers for PV were applied to DNA from 15 frozen, unfixed cervical tissue samples. Unfixed tissue was not available from the remaining 3 baboons. Amplification products of the anticipated size (450 bp) were identified in 6 of the 15 samples (baboons Nos. 1-6), all of which had been histologically identified as having αPV-like changes (koilocytes and/or dysplasia) (Table 1). These 6 samples were further sequenced and identified as 3 novel αPVs, with each virus present in 2 animals. One sequence, provisionally named PhPV1, was found in baboon No. 1, the animal with CIN2 (moderate) cervical dysplasia. A PhPV1 variant (92% nt similarity in MY-L1 region) was identified in a second animal (baboon No. 3) with CIN1 (low grade) dysplasia. The second novel sequence, named PhPV2, was identified in baboon No. 2, which had low-grade (CIN 1) lesions, and in a second animal (baboon No. 5) with only koilocyte-type changes. The third novel sequence, designated PhPV3, was identified in baboon Nos. 4 and 6, both of which had only koilocyte-type lesions. A correlation of PhPV status with the original C. trachomatis inoculation study was not evident, since 1 of the baboons (baboon No. 5) with identified PhPV infection was a control (sham inoculated).

Sequence Analysis of PhPV1

The complete sequence of PhPV1 (8008 bp, GC content 49.6%) contains the classical 6 early (E6, E7, E1, E2, E4, and E5) and 2 late (L2 and L1) ORFs. The putative E6 ORF contains two zinc-binding domains (CxxC(x)29 CxxC), separated by 36 amino acids. A PDZ-binding motif (x-T/S-x-V) is present in the carboxy terminus. PDZ-domain-containing proteins including hDlg, hScrib, MAGI-1, MAGI-2, MAGI-3, and MUPP1 are involved in a variety of cellular functions such as cell signaling and cell adhesion. High-risk HPV E6s (e.g., HPV16, HPV18) have been shown to interact with and degrade these proteins through the C-terminal motif, suggesting that this PDZ domain-binding motif plays a critical role in E6-induced oncogenesis.15 Several NHP PVs within the alpha 12 (α12) species group (MfPV3, −4, −6, −7, −8, −10, and −11) also contain the PDZ domain-binding motif at the carboxy terminus of E6.9 The putative E7 ORFs of these genital MfPVs contain a conserved zinc-binding domain, CxxC(x)29 CxxC, and a pRB binding motif (LxCxE). Similar to genital HPV types, the carboxy-terminal region of the E1 proteins contains the highly conserved binding site of the ATP-dependent helicase. A polyadenylation consensus sequence (AATAAA) for the processing of early viral mRNA transcripts is present at the beginning of the L2 gene. The major (L1) and minor (L2) capsid proteins of both types contain a nuclear localization signal at their 3' end. The PhPV1 E4 and E5 ORFs show significant homology with that of α12 PVs; these genes lack initiation/start codons and are supported to be translated from a spliced transcript.

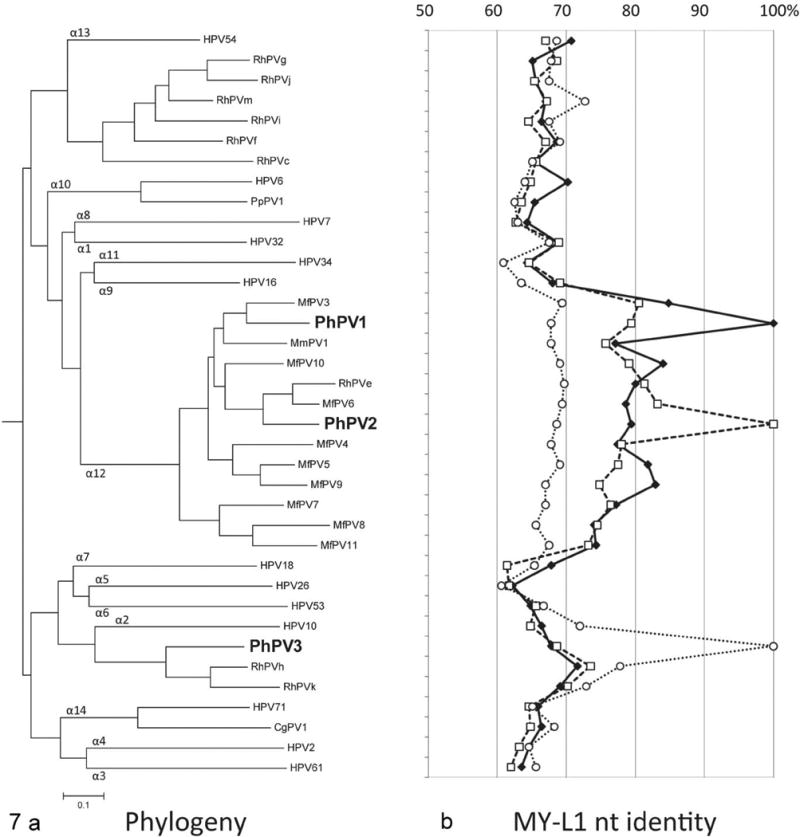

Phylogenetic Analysis of PhPV1, PhPV2, and PhPV3

Phylogenetic analysis inferred from the L1 consensus sequence clustered PhPV1 and PhPV2 within the α12 species group that includes the majority of genital macaque papillomaviruses (Fig. 7). In particular, PhPV1 was most closely related to MfPV3 (83.5% similarity of the complete L1 nucleotide sequence), the most common oncogenic genital αPV in cynomolgus macaques.9,31,33 PhPV1 shared on average 77.8% (74.2% to 80.0%) L1 nucleotide sequence similarity with other α12 types. PhPV2 is another genital baboon PV type clustering within the α12 species group, with MfPV6 being its closest relative (84.5% similarity of the MY-L1 region nucleotide sequence). The most closely related human αPVs to PhPV1 and PhPV2 were α9 types (represented by HPV16, the most oncogenic HPV type) and α11 types (represented by HPV34), which have low to moderate oncogenic potential.9,31,33 PhPV3 clustered separately with a small group of rhesus PVs not known to be oncogenic.7,8 The most closely related human PV to PhPV3 was HPV10, which is predominantly associated with cutaneous warts and epidermodysplasia verruciformis, a benign wartlike condition.8,20

Figure 7.

Phylogeny of novel genital baboon papillomaviruses. a. Relationship of PhPV1, 2, and 3 to other genital Alphapapillomaviruses (αPVs). Maximum likelihood methods using the complete L1 nucleotide (capsid) sequence alignment of represented αPVs were used to infer the tree. The MY-L1 nucleotide sequences (partial capsid) were applied if the complete L1 ORF sequences were unavailable. Each αPV species group is indicated by number at branchpoints of the tree. PhPV1 and PhPV2 cluster with the α12 species group, as do the majority of oncogenic rhesus genital papillomaviruses. PhPV1, the type associated with high-grade CIN in one animal in this study, is most closely related to MfPV3, which is the most common oncogenic PV in macaques. HPV16 (highly oncogenic) is the most closely related human type, although it is a different species group (α9). PhPV3 clusters in a separate branch with two partially characterized non-oncogenic macaque types and (more distantly) HPV10, which is associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis (benign epithelial proliferative disease) in humans. b. Percent nucleotide identity of PhPV1, 2, and 3 in comparison with other αPVs. Each line represents the percent nucleotide similarity, based on the MY-L1 nucleotide sequences, between one PhPV type and the other papillomaviruses on the tree. The solid line represents PhPV1, the long dashed line represents PhPV2, and the short dashed line represents PhPV3. For each point on the line, the percent nucleotide similarity can be read from the top of the graph. For example, PhPV1 (solid line) is 100% similar to itself (point value of the solid line adjacent to the position of PhPV1 on the phylogenetic tree) but only 85% similar to its nearest neighbor, MfPV3 (point value of the solid line adjacent to MfPV3). Abbreviations: RhPVe-k, m, rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) papillomaviruses; MfPV3-11, Macaca fascicularis PV 3-11; MmPV1, Macaca mulatta PV 1; PpPV1, Pan paniscus PV 1.

Additional Histological Findings and Related Diagnostic Testing

In addition to epithelial changes, there was mild to severe cervicovaginal lymphocytic to lymphoplasmacytic inflammation in all 18 control and experimentally infected animals (Table 1 and Fig. 5). Germinal centers were occasionally seen. To account for this finding, the tissues were evaluated for additional genital pathogens. While C. trachomatis nucleic acid and/or organism could be detected by culture and/or from the experimentally infected animals, neither cervical inflammation nor epithelial dysplasia/atypia correlated with the experimental C. trachomatis status in the upper tract (oviducts). Additionally, 1 of 2 animals with the highest cervicovaginal inflammation scores was in the control group (baboon 16). In addition to C. trachomatis culture, 5 animals with high levels of cervicovaginal inflammation were screened by PCR for Papiine herpesvirus 2 (common name Herpesvirus papio 2) and were negative. Although gram negative rods and gram positive cocci were seen superficially on the cervical epithelium in some animals, invasive bacteria or fungal elements were not evident with gram or PAS stains.

Geographical Distribution of PhPV1, 2, and 3

The capture sites were reviewed to determine if there was a geographical pattern in the distribution of the identified PhPV viral sequences (Table 1). Baboons are highly territorial and troops are relatively stable with respect to female members. Since baboons were captured by trapping entire troops, capture sites were roughly analogous to separate breeding populations. All PhPV1 and PhPV2 animals (n = 4) originated from the same district. All but 2 were from the same capture site within this district. The 2 PhPV3 animals were from a separate district.

Discussion

In this study, 3 novel αPV types were detected in 6 out of 15 baboon cervical samples subjected to PCR. Although further characterization work of biological behavior and progression is necessary, the identification of dysplasia-associated αPV in the baboon represents an additional potential animal model that may have some advantages over the macaque. Baboons are increasingly utilized as animal models in female reproductive research due to their size, tractability, and the lack of prevalent zoonotic infections such as Macacine herpesvirus 1 (“Herpes B virus”).11 The straight cervix (as compared to the tortuous cervix of the macaque) allows easier cervical evaluation in the live animal. Additionally, the externally obvious changes in the baboon perivulvar and perianal “sex skin” facilitate monitoring of reproductive cycle phase without requiring direct handling of the animals.14,17 Although highly effective vaccines against human oncogenic PV are now available,24 this is unlikely to completely eliminate PV-associated disease in the near term, due both to limited implementation and the fact that the vaccine will not eliminate existing infections. Non-human primate models will continue to be useful in evaluation of next-generation prophylactic vaccines and therapeutics for human oncogenic PV infections.

This study illustrates the problem of unforeseen background conditions in utilizing large animal models of human disease. Although evaluation of the oviducts was not affected, in our original experimental C. trachomatis study the occurrence of cervicovaginal inflammation in both experimental and control animals was problematic. Cervicovaginal lymphocytic and plasmacytic inflammation and germinal center formation in humans are strongly associated with C. trachomatis infection.34 The specificity of this association may not be as robust in non-human primates, since similar inflammation of uncertain etiology has been reported as a background finding in macaques.10,31 Pre-study screening of research baboons for αPV infection, bacterial infections, or other chronic agents such as baboon herpesviruses (Papiine herpesvirus 1 and 2) may be warranted in experimental studies involving histological evaluation of the reproductive tract.

One potential difference between the baboon CIN1 and CIN2 lesions identified in this study and those of humans was the precise location of the lesions and the degree of keratinization at the lesion site. The baboon lesions were identified in the exocervix (cervical os) adjacent to the squamocolumnar junction. This area often had extensive parakeratosis (Fig. 5). In macaques and humans, the exocervix and transformation zone are typically non-keratinized, while vaginal hyperkeratosis may be present under the influence of estrogen. In macaques and humans, higher grade (CIN2 and CIN3) αPV lesions most commonly arise at the squamocolumnar junction or the adjacent (non-keratinized) transformation zone.30,32,34 The transformation zone is a portion of the endocervical glandular epithelium that everts and undergoes squamous metaplasia at sexual maturity, effectively moving the squamocolumnar junction anteriorly.31,34 In humans, the transformation zone and exocervix may undergo keratinization under the influence of estrogen or infection, including αPV infection.30,32,34 In baboons, the estrogen-influenced vaginal epithelium normally has more pronounced and exophytic hyperkeratosis than in humans. Baboons have prominent vaginal ridges that can extend as papilliform folds to the level of the cervical os.14,17 In light of this, exocervical hyperkeratosis may be a species-dependent variation. In retrospect, sagittal sections (rather than transverse) through the squamocolumnar junction would have been preferable to illustrate lesion orientation.31 It is possible that in some cases, oncogenic αPV may affect the vaginal epithelium. Intriguingly, vulvar and perineal squamous cell carcinomas have been reported in baboons.13 In humans, oncogenic αPV infections are associated with vaginal and vulvar carcinomas as well as vaginal/cervical carcinomas.34 These aspects warrant further scrutiny.

From a phylogenetic standpoint, this study suggests that genital αPVs associated with dysplasia of the female reproductive tract may be more widespread in non-human primate species than previously recognized. Female genital αPV infections have been previously described in cynomolgus and rhesus macaques,9,10,31–33 colobus monkeys,21,26 and humans, but CIN lesions have been described only in humans and macaques.3,9,10,32–34 PhPV1 and PhPV2, the αPV types associated with CIN lesions in this study, were most closely related to known oncogenic αPVs in macaques and in humans, supporting the idea that genital αPVs are ancestral pathogens of various Old World primate species. Phylogenetic comparison of genital αPVs from a variety of species and geographic locations may contribute to our understanding of oncogenic viral evolution. Screening of wild-caught or free-ranging populations may be useful in this regard. For species such as baboons, that are strongly territorial with relatively stable breeding groups, capture sites may serve as a proxy for defined breeding populations. As PV screening can be performed on DNA isolated from cervical swabs taken from sedated animals, euthanasia and invasive tissue sampling is not necessary and screening can be performed in conjunction with other experimental studies or conservation/animal relocation projects.

In summary, the unexpected identification of αPV-associated cervical dysplasia in baboons was fortuitous both as an additional potential animal model of human disease and for its contribution to our understanding of oncogenic viral evolution. Furthermore, it serves as a reminder to maintain a high index of suspicion for background conditions in the pathological evaluation of large animal models of human disease. In some cases, these conditions may be poorly characterized or undescribed and may complicate evaluation of the system of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hermina Borgerink and Jean Gardin of Wake Forest School of Medicine and Paula Arrowsmith and Carrie Schray of the University of Michigan Pathology Cores for Animal Research for their technical contributions.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: JDB was partially supported by a Family Planning Fellowship grant and the National Institutes of Health grant K12 HD065057. ZC, RDB, and CEW were supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R21 AI083962 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). ZC and RDB were also supported by the Einstein-Montefiore Center for AIDS funded by the NIH (AI-51519) and the Einstein Cancer Research Center (P30CA013330) from the National Cancer Institute. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of the NIAID or NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Antonsson A, Hansson BG. Healthy skin of many animal species harbors papillomaviruses which are closely related to their human counterparts. J Virol. 2002;76:12537–12542. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12537-12542.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell JD, Bergin IL, Harris LH, et al. The effects of a single cervical inoculation of Chlamydia trachomatis on the female reproductive tract of the baboon. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1305–1312. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard HU, Burk RD, Chen ZG, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology. 2010;401:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burk RD, Ho GYF, Beardsley L, et al. Sexual behavior and partner characteristics are the predominant risk factors for genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. J Infecti Dis. 1996;174:679–689. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campo MS. Animal models of papillomavirus pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2002;89:249–261. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castle PE, Schiffman M, Gravitt PE, et al. Comparisons of HPV DNA detection by MY09/11 PCR methods. J Med Virol. 2002;68:417–423. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan SY, Bernard HU, Ratterree M, et al. Genomic diversity and evolution of papillomaviruses in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1997;71:4938–4943. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.4938-4943.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan SY, Ostrow RS, Faras AJ, et al. Genital papillomaviruses (PVs) and epidermodysplasia verruciformis PVs occur in the same monkey species: implications for PV evolution. Virol. 1997;228:213–217. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, van Doorslaer K, DeSalle R, et al. Genomic diversity and interspecies host infection of alpha12 Macaca fascicularis papillomaviruses (MfPVs) Virol. 2009;393:304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cline JM, Wood CE, Vidal JD, et al. Selected background findings and interpretation of common lesions in the female reproductive system in macaques. Toxicologic Pathology. 2008;36:142s–163. doi: 10.1177/0192623308327117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Hooghe TM, Kyama CK, Mwenda JM. Baboon model for endometriosis. In: VandeBerg JL, Williams-Blangero S, Tardif SD, editors. The Baboon in Biomedical Research. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forslund O, Antonsson A, Nordin P, et al. A broad range of human papillomavirus types detected with a general PCR method suitable for analysis of cutaneous tumours and normal skin. J General Virol. 1999;80:2437–2443. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-9-2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haddad JL, Dick EJ, Guardado-Mendoza R, et al. Spontaneous squamous cell carcinomas in 13 baboons, a first report in a spider monkey, and a review of the non-human primate literature. J Med Primatol. 2009;38:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2009.00338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hafez RSE, Jaszczak S. Comparative anatomy and histology of the cervix uteri in non-human primates. Primates. 1972;13:297–316. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiyono T, Hiraiwa A, Fujita M, et al. Binding of high-risk human papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins to the human homologue of the Drosophila discs large tumor suppressor protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:11612–11616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight CG, Munday JS, Peters J, et al. Equine penile squamous cell carcinomas are associated with the presence of equine papillomavirus type 2 DNA sequences. Vet Pathol. 2011;48:1190–1194. doi: 10.1177/0300985810396516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Micha JP, Quimby F. Baboon cervical colposcopy, histology, and cytology. Gynecologic Oncology. 1984;17:308–313. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(84)90216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munday JS, Kiupel M. Papillomavirus-associated cutaneous neoplasia in mammals. Vet Pathol. 2010;47:254–264. doi: 10.1177/0300985809358604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nam EJ, Kim JW, Kim SW, et al. The expressions of the Rb pathway in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; predictive and prognostic significance. Gynecologic Oncology. 2007;104:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obalek S, Favre M, Szymanczyk J, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) types specific of epidermodysplasia-verruciformis detected in warts induced by HPV3 or HPV3- related types in immunosuppressed patients. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1992;98:936–941. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12460892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obanion MK, Sundberg JP, Shima AL, et al. Venereal Papilloma and Papillomavirus in a Colobus Monkey (Colobus-Guereza) Intervirology. 1987;28:232–237. doi: 10.1159/000150020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostrow RS, Mcglennen RC, Shaver MK, et al. A Rhesus-Monkey model for sexual transmission of a papillomavirus isolated from a squamous-cell carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:8170–8174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.8170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. International J Cancer. 2006;118:3030–3044. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Price RA, Tiro JA, Saraiya M, et al. Use of human papillomavirus vaccines among young adult women in the United States: an analysis of the 2008 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2011;117:5560–5568. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prophet EB. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Laboratory Methods in Histotechnology. American Registry of Pathology; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reszka AA, Sundberg JP, Reichmann ME. In vitro transformation and molecular characterization of colobus monkey venereal papillomavirus DNA. Virology. 1991;181:787–792. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90919-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terai M, Burk RD. Characterization of a novel genital human papillomavirus by overlapping PCR: candHPV86 identified in cervicovaginal cells of a woman with cervical neoplasia. J General Virol. 2001;82:2035–2040. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-9-2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terai M, Burk RD. Identification and characterization of 3 novel genital human papillomaviruses by overlapping polymerase chain reaction: candHPV89, candHPV90, and candHPV91. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;185:1794–1797. doi: 10.1086/340824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson BA, DeFrias D, Gunn R, et al. Significance of extensive hyperkeratosis on cervical/vaginal smears. Acta Cytologica. 2003;47:749–752. doi: 10.1159/000326600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wood CE. Morphologic and immunohistochemical features of the cynomolgus macaque cervix. Toxicologic Pathology. 2008;36:119s–129s. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood CE, Borgerink H, Register TC, et al. Cervical and vaginal epithelial neoplasms in cynomolgus monkeys. Veterinary Pathology. 2004;41:108–115. doi: 10.1354/vp.41-2-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood CE, Chen Z, Cline JM, et al. Characterization and experimental transmission of an oncogenic papillomavirus in female macaques. J Virol. 2007;81:6339–6345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00233-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright TC, Kurman RJ, Ferenczy AF. Precancerous lesions of the cervix. In: Kurman RJ, editor. Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. 5th. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. pp. 253–254. [Google Scholar]