Abstract

Potent and selective S1P3 receptor (S1P3-R) agonists may represent important proof-of-principle tools used to clarify the receptor biological function and assess the therapeutic potential of the S1P3-R in cardiovascular, inflammatory and pulmonary diseases. N,N-Dicyclohexyl-5-propylisoxazole-3-carboxamide was identified by a high-throughput screening of MLSMR library as a promising S1P3-R agonist. Rational chemical modifications of the hit allowed the identification of N,N-dicyclohexyl-5-cyclopropylisoxazole-3-carboxamide, a S1P3-R agonist endowed with submicromolar activity and exquisite selectivity over the remaining S1P1,2,4,5-R family members. A combination of ligand competition, site-directed mutagenesis and molecular modeling studies showed that the N,N-dicyclohexyl-5-cyclopropylisoxazole-3-carboxamide is an allosteric agonist and binds to the S1P3-R in a manner that does not disrupt the S1P3-R–S1P binding. The lead molecule herein disclosed constitutes a valuable pharmacological tool to explore the molecular basis of the receptor function, and provides the bases for further rational design of more potent and drug-like S1P3-R allosteric agonists.

Keywords: S1P3 receptor, Allosteric agonist, Cardiovascular functions

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a naturally occurring lysophospholipid produced in most cell types, regulates fundamental biological processes and functions including cell proliferation, cell growth, angiogenesis, and inhibits apoptosis and lymphocyte trafficking. 1 The generation of S1P is mediated by two cytosolic sphingosine kinase isoforms (SPK1 and SPK2) and occurs preferentially in the plasma membrane.2 S1P has two distinct signaling roles, as an intracellular second messenger and as an extracellular ligand for a specific family of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) named S1P1–5-Rs.3 S1P can also affect cell function by either binding or modifying putative intracellular targets or by affecting the relative levels of other lipid products, particularly sphingomyelin and ceramide whose biological effects oppose those of S1P.4,2a

Increasing evidence supports that different subfamilies of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters contribute to, or are involved in, secreting the S1P lipids across the plasma membranes.5 The differential temporal and spatial pattern and intracellular signaling pathways of each S1P-R enable S1P to exert its diverse biological functions. S1P1–3-Rs are widely expressed in almost all organs in mice and humans whereas S1P4-R and S1P5-R expression is restricted to specific organs and cell types.6 In humans S1P3-R is highly expressed in heart, lungs, spleen, kidney and pancreas. S1P3-R couples with Gi/o, Gq, and G12/13. Interestingly, S1P3-R deficient mice showed no obvious phenotype.7 However, clear association of S1P3-R has been demonstrated in several cardiovascular functions including regulation of heart rate and blood pressure in rodents,8 vasorelaxation9 and cardiac fibrosis.10 Additionally, regulation of myocardial perfusion and cardiomyocytes protection in ischemia perfusion injury was dependent on the S1P3-R.11 Furthermore, studies with S1P3-R-null mice and PAR1-deficient dendritic cells (DC) have shown that S1P3-R acts as a downstream component in PAR1-mediated septic lethality.12 S1P3-R is also shown to regulate the endothelial cells in splenic marginal sinus organization13 and the stimulation of endothelial progenitor cells.14 S1P3-R has also been implicated in mediating and amplifying inflammatory responses in various CNS disorders in autocrine and paracrine fashion.15 Recently, it has been shown that S1P3-R is markedly up-regulated in a subset of adenocarcinoma cells, and knock down of this receptor subtype inhibits proliferation and growth of lung adenocarcinoma cells.16

A wealth of S1P-Rs agonists has been described in the literature. However, the development of subtype selective S1P3-R agonists as useful pharmacological tools has been limited as a consequence of targeting the orthosteric binding site for receptor activation. The orthosteric binding site displays a high level sequence homology among the S1P-R family subtypes. S1P1-R and S1P3-R are the most closely related by sequence, particularly at their agonist binding pockets which consist of a lower hydrophobic and an upper polar region where Leu-276 in S1P1-R and Phe-263 in S1P3-R are the main difference. Receptor structure modeling and ligand docking studies revealed that the S1P3-R binding pocket is contracted between the lower lipophilic area and the upper polar section by 1.5–1.8 Å compared to the S1P1-R due to the presence of Phe-263. These differences in steric and space constrains in the S1P3-R orthosteric binding site may explain the difficulty in designing S1P3-R agonists devoid of S1P1-R agonist activity.17

Topologically distinct from the conserved orthosteric binding site, an allosteric site provides a means to overcome important selectivity issues associated with the orthosteric ligands, in particular within GPCRs in which the orthosteric site is highly conserved between subtypes. In addition to offering a potential subtype-selectivity, allosteric ligands may stabilize different conformations and functional states, thus activating a distinct repertoire of receptor signaling and regulatory properties that orthosteric ligands are unable to initiate.18 The S1P binding site is highly conserved among the S1P-R family thus selective allosteric ligands may be useful pharmacological tools to decipher individual receptor biological functions.

A high-throughput screening (HTS) of the Molecular Libraries-Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) library identified the N,N-dicyclohexyl-5-propylisoxazole-3-carboxamide 1a (Fig. 1) as a S1P3-R agonist with acceptable in vitro potency/selectivity profile. 17,19 The structural integrity of the hit was corroborated by the re-synthesis (Scheme 1) of the title compound that showed confirmed EC50’s of 434 nM at S1P3-R, 7.87 µM at S1P1-R and no agonist activity at S1P2,4-Rs at concentrations up to 50 µM (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

HTS S1P3-R agonist hit 1a.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 1a–d. Reagents and conditions: (i) (a) 2 (1 equiv), SOCl2, benzene, reflux, 3 h; (b) 3a–d (1.5 equiv), DIPEA (1.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C–rt, 3 h, 70– 98% (over two steps).

Our SAR studies commenced varying the amide region C. The synthesis and biological results of 1b–d are outlined in Scheme 1. The carboxylic acid 2 was transformed into the corresponding acid chloride and coupled with amines 3b–d to furnish the amide products 1b and 1d. Surprisingly, exchanging a cyclohexyl from 1a for a cyclopentyl group (1b) led to loss in potency of 18-fold for the S1P3-R but only of three-fold for the S1P1-R. Furthermore, changing a cyclohexyl for a phenyl (1d) or hydrogen (1c) led to complete loss of potency at both receptors. These results underscore the key role played by the N,N-dicyclohexyl amide for binding to the S1P3-R.

Next we explored region A of the HTS-hit while keeping regions B and C constant. Compounds 5a–i (Table 1) were synthesized from a series of isoxazole carboxylic acids 4a–i commercially available (4a–c and 4f–i) or readily obtained (4d and 4e) according to literature procedures (Scheme 2).20

Table 1.

S1P3-R agonist activity of compounds 5a–i

| Compd | Carboxylic acid | R | EC50α (nM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1P3-R | S1P1-R | |||

| 5a | 4a | Isobutyl | 1375 | 6420 |

| 5b | 4b | Isopropyl | 959 | 22,250 |

| 5c | 4c | Methyl | 6595 | >50,000 |

| 5d | 4d | Cyclohexyl | 559 | >50,000 |

| 5e | 4e | Cyclopentyl | 339 | >50,000 |

| 5f | 4f | Cyclopropyl | 105 | 33,300 |

| 5g | 4g | Phenyl | 103 | 662 |

| 5h | 4h | 4-Methoxyphenyl | 323 | 859 |

| 5i | 4i | 3,4-Diethoxyphenyl | 8070 | 1104 |

Data are reported as mean of n = 3 determinations.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 5a–i. Reagents and conditions: (i) (a) 4a–h (1 equiv), SOCl2, benzene, reflux, 3 h; (b) 3a (1.5 equiv), DIPEA (1.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C–rt, 3 h, 85– 98% (over two steps).

Interestingly, the isobutyl 5a was approximately three-fold less potent than the hit at the S1P3-R and four-fold less selective against the S1P1-R. The isopropyl derivative 5b was approximately two-fold less active than 1a for the S1P3-R, but the selectivity against the S1P1-R remained similar. The methyl derivative 5c was 15-fold less potent than 1a. Remarkably, the cyclohexyl (5d) and cyclopentyl (5e) analogs were slightly less and more active at the S1P3-R and inactive at the S1P1-R. Of note, the cyclopropyl derivative 5f (CYM5541) was found four-fold more potent than the hit and nearly 18-fold more selective against the S1P1-R. The phenyl derivative 5g (CYM5544) was found equipotent to 5f for the S1P3-R but significantly less selective against the S1P1-R. Interestingly, the 4-methoxyphenyl 5h was slightly more potent than the hit compound at the S1P3-R, but its selectivity against the S1P1-R was less than three-fold. Intriguingly, 3,4-diethoxyphenyl 5i was 18-fold less potent than the hit at the S1P3-R but more active (~7-fold) at the S1P1-R. All this information together indicates that an aromatic ring at position five of the isoxazole hit (portion A), although favorable for the S1P3-R activity, is also detrimental for the selectivity against the S1P1-R.

Based on the obtained results, we focused our attention on the SAR studies of 5f, particularly on the amide region C. The synthesis of 7a–l is depicted in Scheme 3. The biological results are listed in Table 2.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 7a–l. Reagents and conditions: (i) (a) 4d (1 equiv), SOCl2, benzene, reflux, 3 h; (b) 3a, 3c, 6a–j (1.5 equiv), DIPEA (1.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C–rt, 3 h, 65–98% (over two steps).

Table 2.

S1P3-R agonist activity of compounds 7a–l

| Compd | Amine | R1 | R2 | EC50α (nM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1P3-R | S1P1-R | ||||

| 7a | 3c | H | Cyclohexyl | >50,000 | >50,000 |

| 7b | 3b | Cyclopentyl | Cyclohexyl | 1683 | >50,000 |

| 7c | 6a | 4-Tetrahydropyranyl | Cyclohexyl | 3536 | >50,000 |

| 7d | 6b | Cyclohexylmethyl | Cyclohexyl | 3430 | >50,000 |

| 7e | 6c | 2-Methylcyclohexyl | Cyclohexyl | 337 | 33,100 |

| 7f | 6d | 2-Methylcyclohexyl | 2-Methylcyclohexyl | 202 | >50,000 |

| 7g | 6e | 2-Methylcyclohexyl | Cycloheptyl | 535 | 4700 |

| 7h | 6f | 2-Methylcyclohexyl | 4-Tetrahydropyranyl | 2820 | 3260 |

| 7i | 6g | 2-Methylcyclohexyl | Cyclopentyl | 1740 | >50,000 |

| 7j | 6h | Cyclopentyl | Cycloheptyl | 2753 | 34,150 |

| 7k | 6i | Phenyl | Benzyl | 7000 | 44,900 |

| 7l | 6j | 2-Pyridinyl | Benzyl | 6563 | >50,000 |

Data are reported as mean of n = 3 determinations.

As previously observed, removal of a cyclohexyl group (7a) led to complete loss of activity. Similarly, exchanging a cyclohexyl for a cyclopentyl (7b), 4-tetrahydropyranyl (7c) or cyclohexylmethyl (7d) led to 16-, 33- and 32-fold loss of potency, respectively, confirming the importance of the bicyclohexyl amide system. Interestingly, the 2-methylcyclohexyl derivative 7e (CYM5558) was three-fold less potent and selective than 5f, probably due to conformational changes caused by the methyl group. Unexpectedly, when both cyclohexyls were substituted with a methyl group (7f, CYM5556) the potency decreased by only two-fold compared to 5f and the selectivity remained nearly similar. The N-(2-methylcyclohexyl)- N-cycloheptyl derivative 7g was almost two-fold less potent than 7e while the 4-tetrahydropyranyl 7h was slightly more potent than the cyclohexyl derivative 7c, although the selectivity of both compounds decreased considerably. Surprisingly, the cyclopentyl 7i was nearly equipotent to 7b. Furthermore, the N-cyclopentyl-N-cycloheptyl derivative 7j was 26-fold less potent than 5f. Not surprisingly, the installation of an aromatic substituent (e.g., 7k and 7l) led to drastic loss in potency.

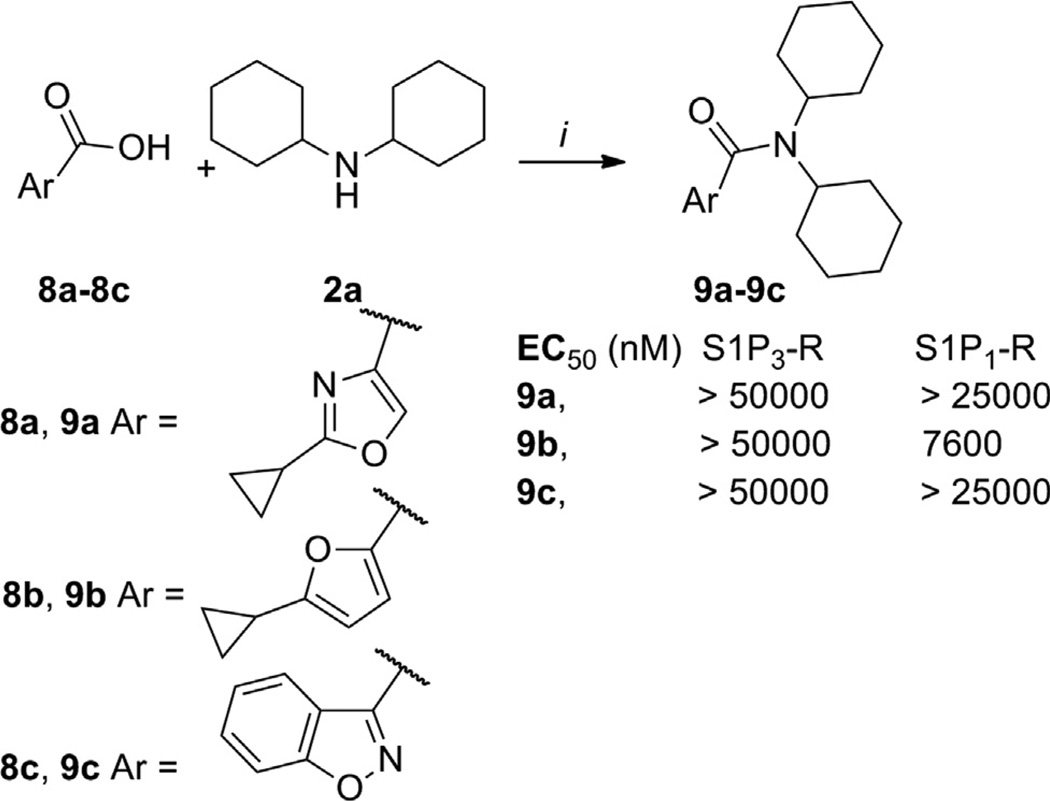

Next, we explored the middle region B holding constant the bicyclohexyl amide region C as well as the cyclopropyl and phenyl groups from region A. The synthesis and biological activity of representative compounds 9a–c is depicted in Scheme 4. Interestingly the oxazole 9a and the furan 9b were inactive at the S1P3-R; interestingly, 9b showed micromolar activity for the S1P1-R. Fusing the phenyl ring of 5g into the isoxazole moiety led to 9c, which was inactive at the S1P3-R. This modification highlights the isoxazole ring as an important binding motif of this chemotype.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of 9a–c. Reagents and conditions: (i) (a) 8a–c (1 equiv), SOCl2, benzene, reflux, 3 h; (b) 2a (1.5 equiv), DIPEA (1.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C–rt, 3 h, 70– 98% (over two steps).

The functional activity of selected compounds was tested against the S1P2,4-Rs subtypes (Table 3).17 Remarkably, all the compounds were highly selective against the S1P2,4-Rs. Due to its selectivity profile, 5f was also tested against the S1P5-R. Remarkably 5f was found exquisitely selective against S1P1,2,4,5-R subtypes.

Table 3.

S1P2,4,5-Rs selectivity counter screen of selected compounds

| Compd | EC50α (nM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1P3-R | S1P1-R | S1P2-R | S1P4-R | S1P5-R | |

| 3a | 434 | 7870 | >50,000 | >50,000 | NT |

| 5b | 959 | 22,250 | >50,000 | >50,000 | NT |

| 5f | 105 | 33,300 | >50,000 | >50,000 | >25,000 |

| 5g | 103 | 662 | >50,000 | >50,000 | NT |

| 5h | 323 | 859 | >50,000 | >50,000 | NT |

| 7f | 202 | >50,000 | >50,000 | >50,000 | NT |

| 7e | 337 | 33,100 | >50,000 | >50,000 | NT |

| 7g | 535 | 4703 | >50,000 | >50,000 | NT |

NT = not tested.

Data are reported as mean of n = 3 determinations.

The selectivity profile of 5f was further investigated against the Ricerca panel of off target proteins including GPCRs, enzymes and ion channels at a concentration of 30 µM. The compound was found to be highly selective against the pool of therapeutically relevant targets tested (stimulation/inhibition <50% at 30 µM). A borderline inhibition (≥50%) was found for CYP450 2C19, CYP450 3A4, norepinephrine transporter, cannabinoid CB1-R, histamine H1-R, and sodium channel site two. Moderate activation (50%) was found only for nicotinic acetylcholine receptor.

The properties of 5f were further examined through a competitive binding experiment using [33P]S1P as the orthosteric binding ligand and S1P as the competitive agonist in the control experiment. We found that S1P competes with [33P]S1P for the S1P3-R binding pocket. Remarkably, 5f does not compete with [33P]S1P for the binding pocket of the S1P3-R and binds in a manner that does not disturb the [33P]S1P–S1P3-R binding.21 Site-directed mutagenesis of S1P1-R/S1P3-R and docking studies performed on an S1P3-homology model showed that 5f binds in an allosteric binding pocket.

Even though 5f is a highly selective S1P3-R agonist with appropriate potency for further biological studies, its physicochemical properties remain suboptimal (tPSA = 41.9, ClogP = 3.9, solubility in PBS = 1.24 µM).

Based on the characterized ligand/binding pocket interactions, our research group will embark on a medicinal chemistry program aiming to further improve the potency and physicochemical properties while maintaining selectivity of 5f.

In summary, rational chemical modifications of the MLSMR hit 1a led to the development of S1P3-R agonists 5f, 7e and 7f (CYM5541, CYM5558, CYM5556) exquisitely selective against the remaining S1P1,2,4,5-R subtypes. Noteworthy, we have reported the discovery, design and synthesis of the first small molecule S1P3-R allosteric agonist based on a N,N-dicyclohexyl-5-alkylisoxazole- 3-carboxamide chemotype, 5f, that is highly selective against a panel of therapeutically relevant targets. The studies herein described provide novel pharmacological tools to decipher the biological function and assess the therapeutic utility of the S1P3-R. Further studies of our research program aiming to improve physicochemical properties and potency while maintaining selectivity will be communicated in due course.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health Molecular Library Probe Production Center Grant U54 MH084512 (E.R., P.H. and H.R.) and AI074564 (M.O. and H.R.). We thank Mark Southern for data management with PubChem; and Pierre Baillargeon for compound management efforts of the MLSMR.

References and notes

- 1.(a) Baumruker T, Prieschl EE. Semin. Immunol. 2002;14:57. doi: 10.1006/smim.2001.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Spiegel S. J. Leukocyte Biol. 1999;65:341. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang F, Van Brocklyn JR, Hobson JR, Movafagh S, Zukowska-Grojec Z, Milstien S, Spiegel S. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:35343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lee MJ, Thangada S, Paik JH, Sapkota GP, Ancellin N, Chae SS, Wu M, Morales-Ruiz M, Sessa WC, Alessi DR, Hla T. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:693. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lee MJ, Thangada S, Claffey KP, Ancellin N, Liu CH, Kluk M, Volpi M, Sha’afi RI, Hla T. Cell. 1999;99:301. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Sugimoto N, Takuwa N, Okamoto H, Sakurada S, Takuwa Y. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:1534. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1534-1545.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Garcia JG, Liu F, Verin AD, Birukova A, Dechert MA, Gerthoffer WT, Bamberg JR, English D. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:689. doi: 10.1172/JCI12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Schwab SR, Cyster JG. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1295. doi: 10.1038/ni1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Spiegel S, Milstien S. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;4:397. doi: 10.1038/nrm1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rivera J, Proia RL, Olivera A. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:753. doi: 10.1038/nri2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Van Brocklyn JR, Lee MJ, Menzeleev R, Olivera A, Edsall L, Cuvillier O, Thomas DM, Coopman PJ, Thangada S, Liu CH, Hla T, Spiegel S. J. Cell. Biol. 1998;142:229. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Goetzl EJ, An S. FASEB J. 1998;12:1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hla T, Lee MJ, Ancellin N, Paik JH, Kluk MJ. Science. 2001;249:1875. doi: 10.1126/science.1065323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hla T. Pharmacol. Res. 2003;47:401. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hla T. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;15:513. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:139. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Mitra P, Oskeritzian CA, Payne SG, Beaven MA, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:16394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603734103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kobayashi N, Nishi T, Hirata T, Kihara A, Sano T, Igarashi Y, Yamaguchi A. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:614. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500468-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee Y, Venkataraman K, Hwang S, Han DK, Hla T. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;84:154. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Gräler MH, Bernhardt G, Lipp M. Genomics. 1998;53:164. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Im DS, Heise CE, Ancellin N, O’Dowd BF, Shei GJ, Heavens RP, Rigby MR, Hla T, Mandala S, McAllister G, George SR, Lynch KR. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:14281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Van Brocklyn JR, Gräler MH, Bernhardt G, Hobson JP, Lipp M, Spiegel S. Blood. 2000;95:2624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishii I, Friedman B, Ye X, Kawamura S, McGiffert C, Contos JJ, Kingsbury MA, Zhang G, Brown JH, Chun J. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:33697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Sanna MG, Liao J, Jo E, Alfonso C, Ahn M, Peterson MS, Webb B, Lefebvre S, Chun J, Gray N, Rosen H. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:13839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Forrest M, Sun S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, Card D, Doherty G, Hale J, Keohane C, Meyers C, Milligan J, Mills S, Nomura N, Rosen H, Rosenbach M, Shei G, Singer II, Tian M, West S, White V, Xie J, Proia RL, Mandala S. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;309:758. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.062828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nofer J, van der Giet M, Tölle M, Wolinska I, von Wnuck Lipinski K, Baba HA, Tietge UJ, Gödecke A, Ishii I, Kleuser B, Schäfers M, Fobker M, Zidek W, Assmann G, Chun J, Levkau B. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:569. doi: 10.1172/JCI18004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takuwa N, Ohkura S, Takashima S, Ohtani K, Okamoto Y, Tanaka T, Hirano K, Usui S, Wang F, Du W, Yoshioka K, Banno Y, Sasaki M, Ichi I, Okamura M, Sugimoto N, Mizugishi K, Nakanuma Y, Ishii I, Takamura M, Kaneko S, Kojo S, Satouchi K, Mitumori K, Chun J, Takuwa Y. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010;85:484. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Theilmeier G, Schmidt C, Herrmann J, Keul P, Schäfers M, Herrgott I, Mersmann J, Larmann J, Hermann S, Stypmann J, Schober O, Hildebrand R, Schulz R, Heusch G, Haude M, von Wnuck Lipinski K, Herzog C, Schmitz M, Erbel R, Chun J, Levkau B. Circulation. 2006;114:1403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Means CK, Xiao C, Li Z, Zhang T, Omens JH, Ishii I, Chun J, Brown JH. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;292:H2944. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01331.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niessen F, Schaffner F, Furlan-Freguia C, Pawlinski R, Bhattacharjee G, Chun J, Derian CK, Andrade-Gordon P, Rosen H, Ruf W. Nature. 2008;452:654. doi: 10.1038/nature06663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girkontaite I, Sakk V, Wagner M, Borggrefe T, Tedford K, Chun J, Fischer K. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1491. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walter DH, Rochwalsky U, Reinhold J, Seeger F, Aicher A, Urbich C, Spyridopoulos I, Chun J, Brinkmann V, Keul P, Levkau B, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S, Haendeler J. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:275. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000254669.12675.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer I, Alliod C, Martinier N, Newcombe J, Brana C, Pouly S. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu A, Zhang W, Lee J, An J, Ekambaram P, Liu J, Honn KV, Klinge CM, Lee M. Int. J. Oncol. 2012;40:1619. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schürer SC, Brown SJ, Gonzales-Cabrera PJ, Schaeffer M, Chapman J, Jo E, Chase P, Spicer T, Hodder P, Rosen H. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008;3:486. doi: 10.1021/cb800051m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Amici M, Dallanoce C, Holzgrabe U, Tränkle C, Mohr K. Med. Res. Rev. 2010;30:463. doi: 10.1002/med.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cell line stably transfected with human S1P3-R, nuclear factor of activated T-cell-beta lactamase (NFAT-BLA) reporter construct and the Gα16 pathway coupling protein was used. Cells were cultured in T-175 sq cm flasks at 37 °C and 95% relative humidity (RH). The growth medium consisted of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Media containing 10% v/v heat inactivated bovine growth serum, 0.1 mM NEAA, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 25 mM HEPES, 2 mg/mL 5 mM l-glutamine, 0.2 mg/mL hygromycin B and 1× penicillin-streptomycin. Prior to the start of the assay, cells were suspended to a concentration of 1.25 × 106/mL in phenol red free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Media containing 0.5% charcoal/dextran treated fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mM NEAA, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 25 mM HEPES, and 5 mM l-glutamine. The assay began by dispensing 10 mL of cell suspension to each test well of a 384 well plate. The cells were then allowed to incubate in the plates overnight at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and 95% RH. The next day, 50 nL of test compound (50 µM final concentration) in DMSO was added to sample wells, and DMSO alone (0.5 final concentration) was added to high control wells. Next, S1P prepared in 2% BSA (0.7 micromolar final nominal concentration, corresponding to the EC80 of S1P) was added to the appropriate wells. After 4 h of incubation, 2.2 µL/well of the GeneBLAzer fluorescent substrate mixture, prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol and containing 10 mM probenicid, was added to all wells. The plates were then incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were read on the EnVision plate reader (PerkinElmer Lifesciences, Turku, Finland) at an excitation wavelength of 405 nm and emission wavelengths of 535 and 460 nm.

- 20.Griffioen G. WO2010/142801. 2010

- 21.S1P3 jump-in CHO cells were cultured in T-175 sq cm flasks at 37 °C and 95% RH. The growth media consisted of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Media (DMEM) (with GlutaMAX) containing 10% v/v heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (dialyzed), 0.1 mM NEAA, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 25 mM HEPES, and 1× penicillin–streptomycin–neomycin. On the day before the assay, cells were suspended at a concentration of 0.2 × 106/mL in the growth media and plated at 0.1 × 106/well in a 24-well plate. On the day of the assay, the growth medium was replaced with serum-starvation medium consisted of DMEM (with GlutaMAX) containing 0.1 mM NEAA, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and no antibiotics. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. After 4 h of serum starvation, the medium was removed and the cells were rinsed with 200 µL of ice-cold binding buffer. The binding buffer consisted of 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 15 mM NaF, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.5% fatty acidfree BSA, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail. Experiment 1: for the S1P3 agonist competition assay, 30 µL of increasing concentrations of 5f (final 5f concentrations of 0.001 nM to 10 µM) and 270 µL ice-cold binding buffer containing [33P]S1P (final concentration of 0.1 nM) were added to the cells in each well. Experiment 2: for the control assay, 30 µL of increasing concentrations of cold S1P (final S1P concentrations of 0.001 nM to 10 µM) and 270 µL ice-cold binding buffer containing [33P]S1P (final concentration of 0.1 nM) were added to the cells in each well. For both experiments, the cells were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. The cells were then washed three times with 500 µL ice-cold binding buffer. The cells were lysed with 300 µL 0.5% SDS and transferred to scintillation vials. 5 mL of scintillation cocktail was dispensed into each vial and the vial vortexed. The 33P radioactivity (cpm) was counted for 5 min/vial in a Beckman LS 6000SC counter.