Abstract

Aim

To evaluate vascularisation of the peripheral retina using fluorescein angiography (FA) digital recordings of infants who had been treated with intravitreal bevacizumab (IVB) as sole therapy for zone I and posterior zone II retinopathy of prematurity (ROP).

Methods

A retrospective evaluation was performed of medical records, RetCam fundus images and RetCam fluorescein angiogram videos of 10 neonates (20 eyes) who received intravitreal bevacizumab injections as the only treatment for zone I and posterior zone II ROP between August 2007 and November 2012.

Results

All eyes had initial resolution of posterior disease after IVB injection as documented by RetCam colour fundus photographs. Using a distance of 2 disc diameters from the ora serrata to vascular termini as the upper limit of allowable avascular retina in children, the FA of these infants demonstrated that 11 of 20 eyes had not achieved normal retinal vascularisation.

Conclusions

Although bevacizumab appears effective in bringing resolution of zone I and posterior zone II ROP and allowing growth of peripheral retinal vessels, in our series of 20 eyes, complete normal peripheral retinal vascularisation was not achieved in half of the patients.

Keywords: Embryology and Development, Retina, Neovascularisation, Imaging

Introduction

The incidence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) has increased globally due to advances in the care of very-low-weight premature infants. In a recent review on the incidence of ROP,1 the incidence of all ROP was found to be approximately 60% for infants less than 1500 g in high-income countries. Most cases of ROP regress spontaneously; however, more severe cases need treatment to prevent blindness. In middle-income countries greater numbers of premature infants are being saved; however, screening and treatment of severe ROP is often lacking, which in turn is leading to an increase in blindness due to ROP. Six different studies in India have reported the incidence of severe ROP, ranging from 6.3% to 44.9%.1 Aggressive posterior ROP (AP-ROP) is a severe form of ROP located in zone I or posterior zone II of the retina, and is characterised by rapid progression to advanced stages of disease.2 3 Even with early laser treatment as suggested in the ‘Early Treatment for ROP’ (ETROP) study,4 poor outcomes are still frequently seen in AP-ROP.5 6 Recently, there have been several encouraging reports of the use of intravitreal bevacizumab as an off-label first line of treatment in neonates with severe ROP.7–13

One of the reported benefits of intravitreal bevacizumab as treatment for zone I and posterior zone II ROP is that the development of peripheral retinal vessels continues after treatment, whereas conventional laser therapy leads to permanent destruction of the peripheral retina.14 In the present work, we report on the results of fluorescein angiography (FA) performed on 10 neonates (20 eyes), which we had treated up to 5 years previously with intravitreal bevacizumab as sole therapy for zone I and posterior zone II ROP. We have evaluated the extent of peripheral retinal vessel growth and remaining avascular retina after a single injection of intravitreal bevacizumab.

All cases were treated and examined at Klinik Mata Nusantara (KMN), an eye hospital in Jakarta, Indonesia. This retrospective study was approved by the Medical Committee of KMN.

Patients

In this retrospective study, we reviewed the records of 17 neonates who had FA after IVB for zone I and posterior zone II ROP. For the purposes of this study, we included 10 neonates who had achieved regression of posterior disease in both eyes with a single injection of bevacizumab and had a minimal follow-up period of 24 weeks after IVB. We excluded six neonates who did not achieve resolution of posterior disease or needed additional treatment before resolution of ROP: one neonate with AP-ROP had resolution of zone I ROP in one eye but developed stage 5 ROP in the other eye; another neonate with AP-ROP needed a second IVB injection to achieve resolution of zone I disease in both eyes; two neonates had not achieved resolution of posterior zone II disease at the last follow-up, and another two neonates needed vitrectomy. One neonate had to be excluded because the child was lost to follow-up after 10 weeks.

At time of IVB, 7 of these 10 cases had been diagnosed as having AP-ROP and 3 cases as having posterior zone II ROP without plus disease. When FA was performed more than once, we evaluated the last FA. Fluorescein angiograms of 10 neonates (20 eyes) were thus evaluated. These neonates had been treated with IVB as a first-line therapy between August 2007 and November 2012. In all cases, regression of posterior disease was documented by RetCam fundus photographs. Gestational age at birth ranged from 28–35 weeks post menstrual age (PMA) (mean=30 weeks), birth weight ranged from 1150–1700 g (mean=1393.2 g), PMA at time of IVB ranged from 32–38 weeks (mean=35.5 weeks). The interval between treatment with IVB and FA ranged from 27–224 weeks.

RetCam FA was performed under general anaesthesia in an operating room at KMN. A 10% solution of fluorescein was injected intravenously at a dose of 0.1 mL/kg followed by an isotonic saline flush. None of the patients experienced systemic complications related to FA.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of the medical records of all infants that had been treated with IVB at KMN was performed. We extracted medical records of infants who had demonstrated resolution of zone I and posterior zone II ROP with IVB as sole treatment as documented by RetCam colour fundus photographs. Although we have been treating zone I and posterior zone II ROP with IVB since 2006, RetCam FA only became available to us in the latter part of 2011. The medical records of 10 neonates (20 eyes) who had RetCam FA after IVB were used to document resolution of posterior disease. We reviewed the fluorescein digital videos of these 20 eyes to evaluate the extent of remaining avascular retina.

An estimate of the peripheral retinal non-perfusion in the infants was compared to previously published descriptions of FA in children.15 Blair et al15 concluded that avascular retina extending more than 2 disc diameters (DD) from the ora serrata should be considered abnormal.

Results

General patterns

Digital video recordings of RetCam FA allowed us to distinctly visualise the anterior border of retinal vessel growth and the vascular–avascular junction of 10 infants who had achieved RetCam documented resolution of posterior disease after treatment with IVB for zone I and posterior zone II ROP. Of 20 eyes examined with FA, 11 had incomplete peripheral retina vascularisation (table 1). Of these 11 eyes, 9 had fluorescein leakage at the vascular–avascular junction. The IVB-FA interval of these eyes with incomplete vascularisation ranged from 27 to 224 weeks (median 87.5 weeks). At the time of IVB, the diagnosis in these children with incomplete retinal vascularisation was AP-ROP in seven cases and posterior zone II ROP without plus disease in three cases. The birth weight of these infants ranged from 1150–1700 g with a mean of 1393.2 g. The gestational age ranged from 28–35 weeks with a mean of 30 weeks PMA.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient no. | GA in weeks PMA | Weight (g) | Diagnosis at IVB | PMA at IVB | PMA at last FA (weeks) | Weeks IVB to Last FA | Eye | Avascular peripheral retina, Y/N | Leakage, Y/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28 | 1200 | AP-ROP | 37 | 64 | 27 | Right | N | N |

| Left | N | N | |||||||

| 2 | 35 | 1700 | AP-ROP | 37 | 64 | 27 | Right | Y | Y |

| Left | Y | Y | |||||||

| 3 | 28 | 1700 | POST-ROP | 35 | 46 | 42 | Right | N | N |

| Left | N | N | |||||||

| 4 | 31 | 1700 | AP-ROP | 38 | 84 | 46 | Right | N | N |

| Left | N | N | |||||||

| 5 | 28 | 1200 | AP-ROP | 32 | 78 | 46 | Right | N | N |

| Left | N | N | |||||||

| 6 | 30 | 1700 | AP-ROP | 34 | 92 | 58 | Right | Y | Y |

| Left | Y | Y | |||||||

| 7 | 30 | 1200 | POST-ROP | 37 | 123 | 86 | Right | Y | Y |

| Left | N | N | |||||||

| 8 | 30 | 1150 | POST-ROP | 34 | 123 | 89 | Right | Y | Y |

| Left | Y | Y | |||||||

| 9 | 29 | 1200 | AP-ROP | 36 | 202 | 166 | Right | Y | N |

| Left | Y | N | |||||||

| 10 | 31 | 1182 | AP-ROP | 35 | 259 | 224 | Right | Y | Y |

| Left | Y | Y |

AP-ROP, aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity; FA, fluorescein angiogram; GA, gestational age; IVB, intravitreal bevacizumab injection; PMA, postmenstrual age; POST-ROP, posterior retinopathy of prematurity.

Case reports

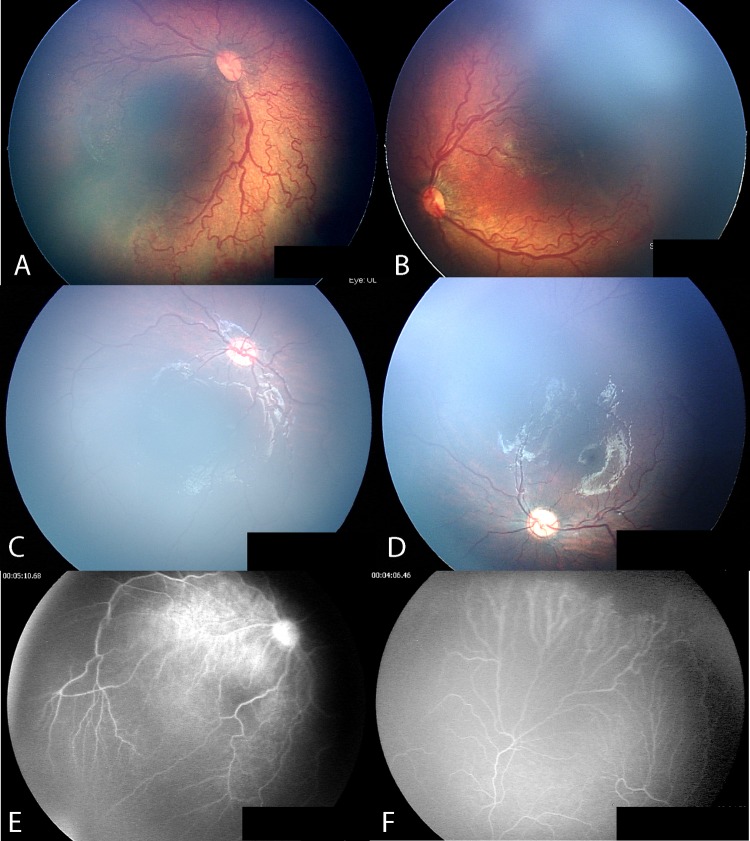

Case no. 5 was a case of AP-ROP (figure 1A,B), which resolved after a single injection of IVB (figure 1C,D). FA performed at 46 weeks after IVB (figure 1E,F) shows less than 2 DD of avascular peripheral retina and no vascular leakage.

Figure 1.

Case no. 5: aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Posterior fundus before intravitreal bevacizumab injection (IVB) (A,B); after injection of IVB (C,D); fluorescein angiography 46 weeks after IVB, demonstrates less than 2 disc diameters (DD) of avascular retina (E,F).

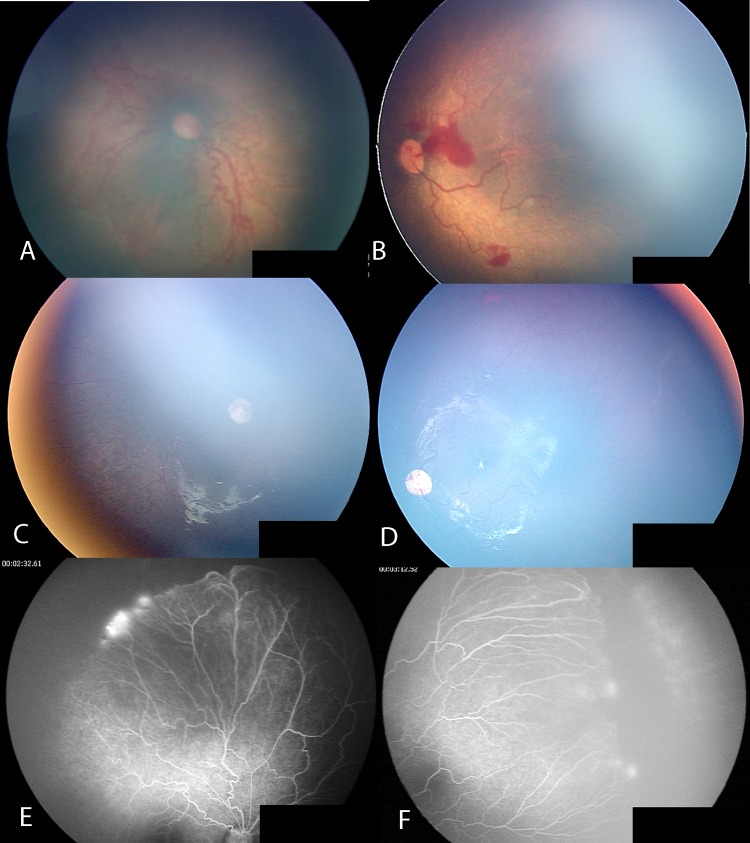

Case no. 10 was a case of AP-ROP (figure 2A,B), where there was resolution of posterior disease after IVB (figure 2C,D) but the peripheral retina remained avascular with fluorescein leakage at the vascular–avascular junction more than 4 years after IVB treatment (figure 2E,F).

Figure 2.

Case no. 10: aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Posterior fundus before intravitreal bevacizumab injection (IVB) (A,B); resolution of posterior disease after IVB (C,D). The peripheral retina remains avascular with fluorescein leakage more than 4 years after IVB (E,F).

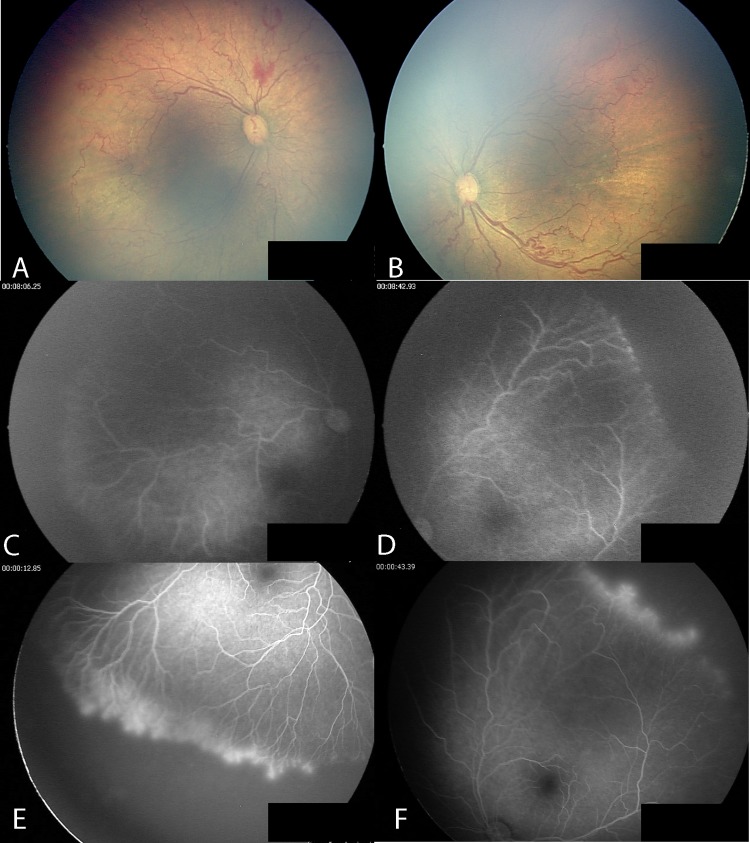

Cases no. 8 and no. 7 are twin neonates who presented with posterior ROP (figures 3A,B and 4A,B, respectively). Case no. 8 had avascular peripheral retinas without fluorescein leakage 21 weeks after IVB treatment (figure 3C,D). FA at 89 weeks after IVB demonstrated that the retina in both eyes remained avascular with fluorescein leakage at the vascular–avascular junction (figure 3E,F).

Figure 3.

Case no. 8: posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Posterior fundus before intravitreal bevacizumab injection (IVB) (A,B); avascular peripheral retina without leakage 21 weeks after IVB (C,D); avascular peripheral retina with fluorescein leakage in both eyes 89 weeks after IVB (E,F).

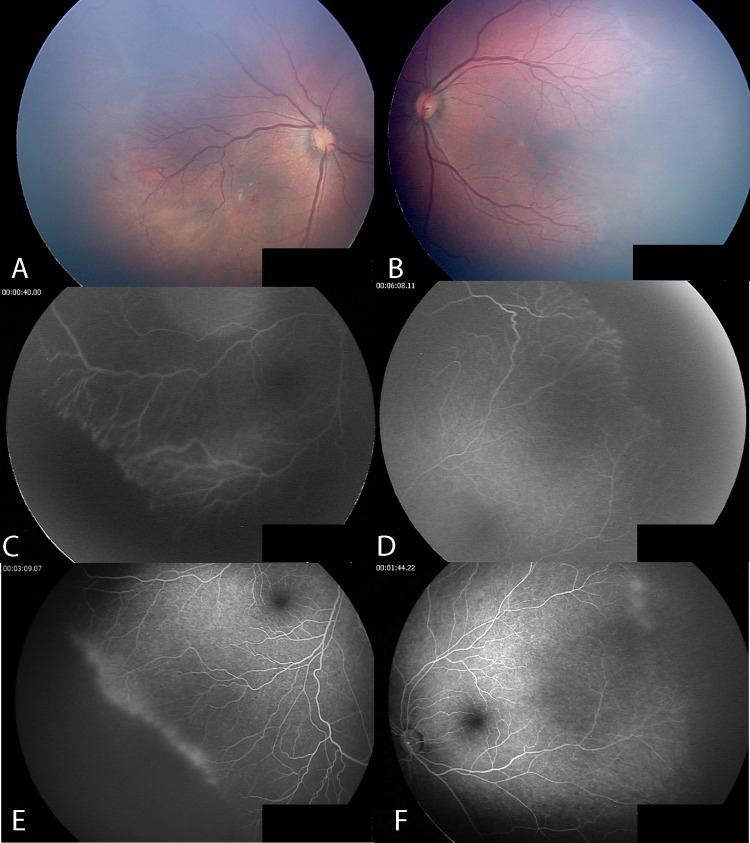

Figure 4.

Case no. 7: posterior retinopathy of prematurity, the twin sister of case no. 8. Posterior fundus before intravitreal bevacizumab injection (IVB) (A,B); avascular peripheral retina without fluorescein leakage in both eyes 18 weeks after IVB (C,D); fully vascularised peripheral retina in the left eye, and avascular retina with fluorescein leakage in the right eye 86 weeks after IVB (E,F).

Case no. 7 had avascular peripheral retinas without leakage 18 weeks after IVB treatment (figure 4C,D). FA performed at 86 weeks after IVB demonstrated that the left peripheral retina was vascularised while the right peripheral retina remained unvascularised and had fluorescein leakage at the vascular–avascular junction (figure 4E,F).

Discussion

Although numerous authors have reported their experience using bevacizumab in the management of ROP,9 10 13 at the time of writing there has been only one controlled trial comparing intravitreal bevacizumab to conventional treatment of ROP, the BEAT ROP trial.10 In that study, the authors concluded that development of peripheral retinal vessels continued after treatment with IVB. In our study, we aimed to evaluate the extent of peripheral retinal growth in eyes with zone I and posterior zone II ROP that were treated with a single injection of intravitreal bevacizumab. Fluorescein angiographic imaging was chosen, as it allowed us to accurately visualise the extent of peripheral retinal vessel growth in these eyes.

In our series of 20 eyes from 10 patients we found that, despite resolution of zone I and posterior zone II ROP after a single injection of IVB, the peripheral retina remained incompletely vascularised in 11 (55%) of the eyes. In addition, we observed fluorescein leakage at the vascular–avascular junction in 9 of these 11 eyes with avascular peripheral retina (82% of total).

The safety of FA in neonates has been established since 2006.16 17 In 2011, Lepore et al, published an atlas of fluorescein angiographic findings in eyes undergoing laser treatment for ROP. The authors concluded that FA clearly defined the zone I junction between vascularised and non-vascularised retina.18 Recently, Velia et al,19 investigated retinal development in premature infants using FA and revealed vascular changes in ROP eyes, such as loss of the normal dichotomous branching, vessel branching at the junction between vascular and avascular retina, arteriovenous shunts, and other abnormalities that were thought to be related to the immaturity of the vascular network. We observed similar findings such as irregular branching of large arterioles and circumferential vessel formation (figure 4C), and fluorescein leakage (figure 3E,F). Of significance, Velia et al19 determined that dye leakage is the most significant sign of progression to severe ROP.

Blair et al15 estimated the normal extent of peripheral retinal non-perfusion in normal children at various postnatal ages. In that study, the authors—using RetCam FA on 33 eyes from 31 normal children—estimated avascular retina using scleral indentation during FA to determine the distance of vascular termini to the ora serrata. None of these normal eyes had a distance greater than 1.5 disk diameters up to 13 years of age. The authors concluded that, conservatively, a distance of greater than 2 DD from the ora to the vascularised retinal margin should be considered abnormal. This data provided a useful practical standard to document the extent of peripheral retinal vascular development when screening infants with ROP using FA.

All neonates in our study had resolution of zone I and posterior zone II ROP documented by RetCam colour imaging at the time FA was performed. Previous studies have reported the favourable response of zone I and posterior zone II ROP to intravitreal injections of bevacizumab.10 20 Our study focuses on the extent of normal retinal vessel growth in the peripheral retina in cases where zone I and posterior zone II ROP had been deemed to have responded favourably to a single injection of IVB as sole treatment.10 14 21 It is often difficult to accurately determine the vascular–avascular junction in the peripheral retina using indirect ophthalmoscopy or colour RetCam images. We therefore chose to use FA, which allows accurate visualisation of the outer borders of the vascular retina.18 19

The birth weight and PMA of the neonates with zone I and posterior zone II disease in our series is higher than reports from similar series from developed countries. Carden et al22 reported that 58 infants referred to the National Hospital of Paediatrics in Hanoi, Vietnam with ROP had birth weights ranging from 800–1900 g and gestational ages ranging from 28–35 weeks. Gu et al23 reported birth weights of infants with ROP in China ranging from 1501–2000 g. Risk factors reported to cause ROP in more mature neonates are septicaemia and poorly controlled oxygen therapy.

Our study showed that 55% of eyes continued to have incomplete vascularisation at time of follow-up examination including up to 259 weeks after birth. In the eyes with the longest IVB-FA interval (case no. 10) there were also numerous areas of lattice degeneration, which may increase the future risk for development of retinal tears and complications after cataract surgery, as has been previously reported.24 25 Although we did not see ridges or extraretinal fibrovascular proliferation in these 11 eyes, there was fluorescein leakage at the vascular–avascular border in 9 eyes. This may be important, as fluorescein leakage has previously been reported to be a sign of progression to severe ROP.19

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that although intravitreal bevacizumab can be very effective in causing resolution of zone I and posterior zone II ROP, ophthalmologists should remain cautious as infants may remain at risk due to avascular peripheral retinas even many years after treatment. Careful examination using FA allows accurate visualisation of risk factors such as the extent of avascular retina and the presence of dye leakage.

Footnotes

Contributors: All work carried out for this study was performed by the listed authors. Review of medical records and fluorescein angiogram digital recordings by SGT and RH. Clinical science and editorial input by GCL (pediatric ophthalmologist) and SK. PGM went over the manuscript numerous times to provide editorial input.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zin A, Gole GA. Retinopathy of prematurity-incidence today. Clin Perinatol 2013;40:185–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz X, Kychenthal A, Dorta P. Zone I retinopathy of prematurity. J Aapos 2000;4:373–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drenser KA, Trese MT, Capone A., Jr Aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Retina 2010;30(4 Suppl):S37–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Good WV, Hardy RJ. The multicenter study of Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity (ETROP). Ophthalmology 2001;108:1013–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azuma N, Ishikawa K, Hama Y, et al. Early vitreous surgery for aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;142:636–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinekar A, Trese MT, Capone A., Jr Evolution of retinal detachment in posterior retinopathy of prematurity: impact on treatment approach. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;145:548–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azad R, Chandra P. Intravitreal bevacizumab in aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Indian J Ophthalmol 2007;55:319; author reply 20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung EJ, Kim JH, Ahn HS, et al. Combination of laser photocoagulation and intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for aggressive zone I retinopathy of prematurity. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007;245:1727–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lalwani GA, Berrocal AM, Murray TG, et al. Off-label use of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for salvage treatment in progressive threshold retinopathy of prematurity. Retina 2008;28:S13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mintz-Hittner HA, Kuffel RR., Jr Intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (avastin) for treatment of stage 3 retinopathy of prematurity in zone I or posterior zone II. Retina 2008;28:831–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quiroz-Mercado H, Martinez Castellanos M, Hernandez-Rojas M, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy with intravitreal bevacizumab for retinopathy of prematurity. Retina 2008;28:S19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Travassos A, Teixeira S, Ferreira P, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab in aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2007;38:233–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kusaka S, Shima C, Wada K, et al. Efficacy of intravitreal injection of bevacizumab for severe retinopathy of prematurity: a pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:1450–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mintz-Hittner HA, Kennedy KA, Chuang AZ. Efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab for stage 3+ retinopathy of prematurity. N Engl J Med 2011;364:603–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blair MP, Shapiro MJ, Hartnett ME. Fluorescein angiography to estimate normal peripheral retinal nonperfusion in children. J Aapos 2012;16:234–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng EY, Lanigan B, O'Keefe M. Fundus fluorescein angiography in the screening for and management of retinopathy of prematurity. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2006;43:85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner RS. Fundus fluorescein angiography in retinopathy of prematurity. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2006;43:78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lepore D, Molle F, Pagliara MM, et al. Atlas of fluorescein angiographic findings in eyes undergoing laser for retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmology 2011;118:168–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velia P, Antonio B, Patrizia P, et al. Fluorescein angiography and retinal vascular development in premature infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25(Suppl 3):53–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorta P, Kychenthal A. Treatment of type 1 retinopathy of prematurity with intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin). Retina 2010;30(4 Suppl):S24–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harder BC, von Baltz S, Jonas JB, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab for retinopathy of prematurity. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2011;27:623–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carden SM, Luu LN, Nguyen TX, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity: postmenstrual age at threshold in a transitional economy is similar to that in developed countries. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2008;36:159–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu MH, Jin J, Yuan TM, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for retinopathy of prematurity in neonatal infants with a birth weight of 1,501–2,000 g in a Chinese Neonatal Unit. Med Princ Pract 2011;20:244–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser RS, Fenton GL, Tasman W, et al. Adult retinopathy of prematurity: retinal complications from cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;145:729–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiser RS, Trese MT, Williams GA, et al. Adult retinopathy of prematurity: outcomes of rhegmatogenous retinal detachments and retinal tears. Ophthalmology 2001;108:1647–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]