Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease involving progressive loss of motoneurons (MN). Axonal pathology and presynaptic deaf-ferentation precede MN degeneration during disease progression in patients and the ALS mouse model (mSOD1). Previously, we determined that a functional adaptive immune response is required for complete functional recovery following a facial nerve crush axotomy in wild-type (WT) mice. In this study, we investigated the effects of facial nerve crush axotomy on functional recovery and facial MN survival in presymptomatic mSOD1 mice, relative to WT mice. The results indicate that functional recovery and facial MN survival levels are significantly reduced in presymptomatic mSOD1, relative to WT, and similar to what has previously been observed in immunodeficient mice. It is concluded that a potential immune system defect exists in the mSOD1 mouse that negatively impacts neuronal survival and regeneration following target disconnection associated with peripheral nerve axotomy.

Keywords: Motoneuron survival, Functional recovery, Axotomy, SOD1, ALS

INTRODUCTION

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease that results in upper and lower motoneuron (MN) loss, accompanying muscle weakness and atrophy.1 Transgenic mice, overexpressing the inherited, human mutant Cu2+/Zn2+ superoxide dismutase-1 gene (mSOD1), develop a similar pathology as ALS patients, including muscle weakness and atrophy, inflammation, and MN degeneration.2–4 In addition, an axonal pathology has been observed where motor axons withdraw from neuromuscular junctions,5 producing an axonal die-back response, which precedes MN degeneration.6–8 Axonal disconnection from neuromuscular junctions in target musculature, afferent presynaptic stripping surrounding the MN centrally,9–11 and immune system activation12–15 are responses that occur both as a result of axonal die-back in ALS and peripheral nerve injury.16–18

Our previous study utilized a well-established experimental peripheral nerve injury, the facial nerve axotomy model, as an investigative tool to begin to delineate potential molecular mechanisms related to MN degeneration in presymptomatic mSOD1 mice.19 The results suggest that the increased susceptibility of mSOD1 MN to injury-induced cell death, and potentially, disease progression, correlates with a dysregulated non-neuronal cellular response surrounding presymptomatic MN.

In addition, immunodeficient mice, lacking mature B and T cells, exhibit a significant loss in facial MN survival and delayed functional recovery after a facial nerve crush injury,20,21 as well as a significant reduction in facial MN survival levels after facial nerve transection.22,23 Therefore, a functional adaptive immune system is required for both neuronal survival and regeneration after peripheral nerve injury.

In this study, we investigated how presymptomatic mSOD1 MN respond to facial nerve crush injury in comparison to WT mice. Both functional recovery times and facial MN numbers were negatively impacted in the mSOD1 mice. Interestingly, the negative impact of the nerve crush on MN survival and regeneration, relative to WT, was similar to that previously observed in immunodeficient mice. It is concluded that a potential immune system defect exists in the mSOD1 mouse that negatively impacts neuronal survival and regeneration following target disconnection associated with peripheral nerve injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and surgical procedures

B6SJL wild-type (WT; n = 4) and transgenic mSOD1G93A (mSOD1; n = 4) female mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory at 7 weeks of age, and permitted 1 week to acclimate to their environment before experimental manipulation. The mice were provided autoclaved pellets and water ad libitum, and housed under a 12-hour light/dark cycle in microisolater cages contained within a laminar flow system to maintain a pathogen-free environment.

All surgical procedures were completed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines on the care and use of laboratory animals for research purposes. The mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane for all surgical procedures. Using aseptic techniques, the right facial nerve was exposed at its exit from the stylomastoid foramen and crushed twice using fine jeweler’s forceps at 180° opposing angles for 30 seconds each.24

Functional recovery assessment

Following facial nerve crush axotomy, loss of eye-blink reflex and vibrissae movement, abnormal vibrissae orientation, where the fibers are flattened in a posterior direction against the head and drooping of the mouth are observed on the ipsilateral side. The contralateral facial nerve remained intact and served as an internal control for comparison.

Functional recovery from nerve crush-induced facial paralysis was examined daily using behavioral observation assessments under “blind” conditions.24 The first assessment was performed immediately after surgery and continued until complete functional recovery was observed compared to the contralateral uninjured side. Complete functional recovery was defined as the return of a full eye-blink reflex, when vibrissae movements were equal in magnitude and orientation relative to the contralateral side. For the eyeblink reflex, a small puff of air is blown into the animal’s face, initiating the eye-blink reflex where the eyelids involuntarily close in response to the air puff; however, facial nerve axonal injury prevents this reflex from occurring.24 The behavioral observations were scored using a 3-point scale (1 = no recovery; 2 = onset of recovery; 3 = full recovery) for the eye-blink reflex, vibrissae movement, and vibrissae orientation.25 Both onset and full recovery for each parameter was determined along with the complete functional recovery.

Facial MN survival

Brains were removed and flash frozen 28 days postcrush. Coronal cryostat sections at 25 μm were collected throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the facial motor nuclei. As previously described,26 the sections were fixed in 4 percent paraformaldehyde and stained with thionin. Facial MN were counted and presented as the average percent of MN survival ± the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was accomplished using unpaired t test, with post hoc power analysis significance at p < 0.05.27

RESULTS

Functional recovery is delayed in crush-injured mSOD1 mice

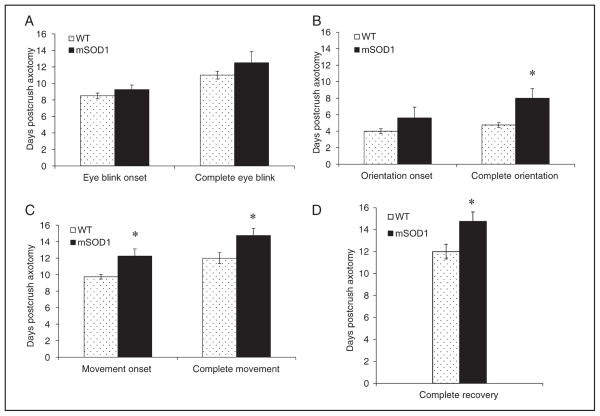

To determine whether facial nerve crush injury influences functional recovery times in presymptomatic mSOD1 mice, recovery times were assessed as the number of days post-crush axotomy ± SEM for onset and full recovery of eye-blink reflex, vibrissae orientation, and vibrissae movement, and for complete functional recovery, relative to WT mice. The onset of a semi-eye blink occurred in mSOD1 mice at 9.3 ± 0.6 days postcrush and WT at 8.5 ± 0.3 days, and the full recovery of the eye-blink reflex was observed in mSOD1 mice at 12.5 ± 1.4 days postcrush and WT at 11 ± 0.5 days (Figure 1A). The onset of vibrissae orientation occurred at 5.6 ± 1.3 days postcrush in mSOD1 mice and 4 ± 0.5 days in WT, while full recovery of vibrissae orientation required 8 ± 1.2 days postcrush in mSOD1 mice compared to 4.8 ± 0.3 days in WT (Figure 1B). The onset and full recovery of vibrissae movement required 12.3 ± 0.9 and 14.8 ± 0.9 days postcrush, respectively, in mSOD1 mice compared to 9.8 ± 0.3 and 12 ± 0.7 days, respectively, in WT (Figure 1C). Complete functional recovery of all the behavioral parameters was observed in mSOD1 mice at 14.8 ± 0.9 days post-crush compared to 12 ± 0.7 days in WT (Figure 1D). The onset of vibrissae movement, full recovery of vibrissae orientation and movement, and complete functional recovery were significantly delayed in presymptomatic mSOD1 mice compared to WT mice in response to a facial nerve crush axotomy.

Figure 1.

Functional recovery time in presymptomatic mSOD1 mice is delayed compared to WT following facial nerve crush. The number of days postcrush to detect the onset and recovery of the eye-blink reflex (A), vibrissae orientation (B), vibrissae movement (C), and complete recovery of all parameters (D). All data are presented as mean recovery time in days postcrush axotomy ± SEM. * represents a significant difference compared to WT, at p < 0.05.

Facial MN survival levels are reduced in crush-injured mSOD1 mice

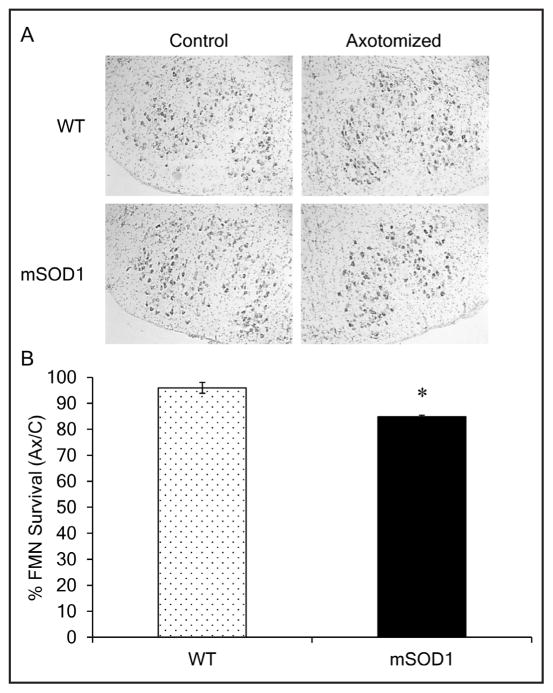

To ascertain how facial nerve crush affects presymptomatic mSOD1 MN numbers, facial MN levels were compared to WT 28 days postcrush. Figure 2A contains representative photomicrographs of uninjured control and crush injured facial motor nuclei sections from WT and mSOD1 mice. In agreement with our previous report,19 no effect of the mSOD1 transgene or disease was observed with regards to the average number of facial MN in the uninjured control facial nucleus of presymptomatic mSOD1 mice relative to WT (1,984 ± 58 and 2,094 ± 116, respectively; data not shown). In contrast to WT facial MN survival levels of 96 ± 2.1%, presymptomatic mSOD1 mice demonstrated a significant reduction in facial MN survival levels of 85 ± 0.6%, relative to the uninjured control nucleus at 28 days postcrush (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Presymptomatic mSOD1 facial MN survival levels are significantly reduced compared to WT 28 days after facial nerve crush. (A) Representative photomicrographs of thionin-stained control and axotomized facial motor nuclei of WT and mSOD1 mice. (B) Average percent survival ± SEM of facial MN from facial nuclei of WT and mSOD1 mice following a facial nerve crush, relative to the uninjured control nuclei. * represents a significant difference compared to WT, at p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

It is well established that MN axons of crush-injured WT mouse, rat, and hamster acquire complete functional recovery at reproducible time intervals, dependent on the species.21,24,25,28 However, complete functional recovery is significantly delayed in immunodeficient mice lacking mature B and T cells,20,21 suggesting that the adaptive immune system influences neural reparative processes. Peripheral MN axonal injury initiates Wallerian degeneration, a tightly regulated response, involving activated immune and Schwann cells, and essential for MN regeneration to occur.6,29–31

In this study, we examined whether presymptomatic mSOD1 MN axons were capable of regenerating after a facial nerve crush injury and, if so, is the return of functional recovery time comparable to WT. Application of the facial nerve injury model in the mSOD1 mouse was conducted to evaluate presymptomatic mSOD1 immune functionality, with regard to immune-mediated neuroprotective effects on MN survival and regeneration. As with nerve transection,19,32 an enhanced MN susceptibility to facial nerve crush injury-induced death is observed; conversely, no effects of disease are evident on facial MN numbers as demonstrated after sciatic nerve crush.33 Our results also reveal that presymptomatic mSOD1 facial MN axons do indeed exhibit the capacity to reconnect with their target musculature after undergoing a facial nerve crush. However, the time for complete functional recovery is significantly delayed compared to the WT response.

Distal axonal degeneration, or axonal die-back, occurs presymptomatically, preceding MN degeneration, in mSOD1 mice,6,7,34 and is associated with neuropathologic changes in the muscle and surrounding MN axons. Previous research in mSOD1 mice demonstrates that distinct immune activation responses occur in peripheral nerves, including antibody secretion levels and complement regulation of macrophage recruitment, compared to the resident glial activation and T cell infiltration in the spinal cord.12,35–37 Despite the robust immune system activation, surviving mSOD1 peripheral MN axons undergo compensatory sprouting to reinnervate motor end-plates in the midst of the symptomatic stage of disease progression, although this compensation phase is transient.6,38

Previous research suggests that the presymptomatic mSOD1 axonal die-back response shares similarities to the WT Wallerian degeneration response after peripheral nerve injury.12,39 In addition, WT splenocytes adoptively transferred into immunodeficient mice prevent the delay in MN axonal functional recovery times after facial nerve crush injury, resulting in recovery times comparable to WT.21 Thus, the delay we observed in complete functional recovery of crush-injured facial motor axons in presymptomatic mSOD1 mice compared to WT mice could be due to either an aberrant macrophage and immune response peripherally and/or dysfunctional glial and immune response centrally that prevents the T cell-mediated neuroprotection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NS40433 (KJJ and VMS).

References

- 1.Rowland LP, Shneider NA. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1688–1700. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng HX, Hentati A, Tainer JA, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and structural defects in Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Science. 1993;261:1047–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.8351519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shibata N. Transgenic mouse model for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with superoxide dismutase-1 mutation. Neuropathology. 2001;21:82–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2001.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dadon-Nachum M, Melamed E, Offen D. The “dying-back” phenomenon of motor neurons in ALS. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;43:470–477. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer LR, Culver DG, Tennant P, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a distal axonopathy: Evidence in mice and man. Exp Neurol. 2004;185:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hegedus J, Putman CT, Gordon T. Time course of preferential motor unit loss in the SOD1 G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;28:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennel PF, Finiels F, Revah F, et al. Neuromuscular function impairment is not caused by motor neurone loss in FALS mice: An electromyographic study. Neuroreport. 1996;7:1427–1431. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199605310-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyazaki K, Nagai M, Morimoto N, et al. Spinal anterior horn has the capacity to self-regenerate in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model mice. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:3639–3648. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikemoto A, Nakamura S, Akiguchi I, et al. Differential expression between synaptic vesicle proteins and presynaptic plasma membrane proteins in the anterior horn of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;103:179–187. doi: 10.1007/s004010100449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zang DW, Lopes EC, Cheema SS. Loss of synaptophysin-positive boutons on lumbar motor neurons innervating the medial gastrocnemius muscle of the SOD1G93A G1H transgenic mouse model of ALS. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:694–699. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu IM, Phatnani H, Kuligowski M, et al. Activation of innate and humoral immunity in the peripheral nervous system of ALS transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20960–20965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911405106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelhardt JI, Tajti J, Appel SH. Lymphocytic infiltrates in the spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:30–36. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540010026013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantovani S, Garbelli S, Pasini A, et al. Immune system alterations in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients suggest an ongoing neuroinflammatory process. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;210:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Inflammatory processes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:459–470. doi: 10.1002/mus.10191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jinno S, Yamada J. Using comparative anatomy in the axotomy model to identify distinct roles for microglia and astrocytes in synaptic stripping. Neuron Glia Biol. 2012:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X11000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones KJ, Serpe CJ, Byram SC, et al. Role of the immune system in the maintenance of mouse facial motoneuron viability after nerve injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moran LB, Graeber MB. The facial nerve axotomy model. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;44:154–178. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mesnard NA, Sanders VM, Jones KJ. Differential gene expression in the axotomized facial motor nucleus of presymptomatic SOD1 mice. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:3488–3506. doi: 10.1002/cne.22718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beahrs T, Tanzer L, Sanders VM, et al. Functional recovery and facial motoneuron survival are influenced by immunodeficiency in crush-axotomized mice. Exp Neurol. 2010;221:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serpe CJ, Tetzlaff JE, Coers S, et al. Functional recovery after facial nerve crush is delayed in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:808–812. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serpe CJ, Sanders VM, Jones KJ. Kinetics of facial motoneuron loss following facial nerve transection in severe combined immunodeficient mice. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:273–278. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001015)62:2<273::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serpe CJ, Kohm AP, Huppenbauer CB, et al. Exacerbation of facial motoneuron loss after facial nerve transection in severe combined immunodeficient (scid) mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19:RC7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-j0004.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kujawa KA, Kinderman NB, Jones KJ. Testosterone-induced acceleration of recovery from facial paralysis following crush axotomy of the facial nerve in male hamsters. Exp Neurol. 1989;105:80–85. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(89)90174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lal D, Hetzler LT, Sharma N, et al. Electrical stimulation facilitates rat facial nerve recovery from a crush injury. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mesnard NA, Alexander TD, Sanders VM, et al. Use of laser microdissection in the investigation of facial motoneuron and neuropil molecular phenotypes after peripheral axotomy. Exp Neurol. 2010;225:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown TJ, Khan T, Jones KJ. Androgen induced acceleration of functional recovery after rat sciatic nerve injury. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 1999;15:289–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avellino AM, Hart D, Dailey AT, et al. Differential macrophage responses in the peripheral and central nervous system during wallerian degeneration of axons. Exp Neurol. 1995;136:183–198. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camara-Lemarroy CR, Guzman-de la Garza FJ, Fernandez-Garza NE. Molecular inflammatory mediators in peripheral nerve degeneration and regeneration. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2010;17:314–324. doi: 10.1159/000292020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taskinen HS, Olsson T, Bucht A, et al. Peripheral nerve injury induces endoneurial expression of IFN-gamma, IL-10 and TNF-alpha mRNA. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;102:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mariotti R, Cristino L, Bressan C, et al. Altered reaction of facial motoneurons to axonal damage in the presymptomatic phase of a murine model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroscience. 2002;115:331–335. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharp PS, Dick JR, Greensmith L. The effect of peripheral nerve injury on disease progression in the SOD1(G93A) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroscience. 2005;130:897–910. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcuzzo S, Zucca I, Mastropietro A, et al. Hind limb muscle atrophy precedes cerebral neuronal degeneration in G93A-SOD1 mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a longitudinal MRI study. Exp Neurol. 2011;231:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graber DJ, Hickey WF, Harris BT. Progressive changes in microglia and macrophages in spinal cord and peripheral nerve in the transgenic rat model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banerjee R, Mosley RL, Reynolds AD, et al. Adaptive immune neuroprotection in G93A-SOD1 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dibaj P, Steffens H, Zschuntzsch J, et al. In Vivo imaging reveals distinct inflammatory activity of CNS microglia versus PNS macrophages in a mouse model for ALS. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaefer AM, Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. A compensatory subpopulation of motor neurons in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Comp Neurol. 2005;490:209–219. doi: 10.1002/cne.20620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kano O, Beers DR, Henkel JS, et al. Peripheral nerve inflammation in ALS mice: Cause or consequence. Neurology. 2012;78:833–835. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318249f776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]