Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated the rate of Hispanic children who have grandparents involved in caretaking and whether grandparents’ involvement has a negative impact on feeding practices, children's physical activity, and body mass index (BMI).

Method

One hundred and ninety-nine children and their parents were recruited at an elementary school. Parents completed a questionnaire regarding their children's grandparents’ involvement as caretakers and the feeding and physical activity practices of that grandparent when with the child. Children's height and weight were measured and zBMI scores were calculated.

Results

Forty-three percent of parents reported that there was a grandparent involved in their child's caretaking. Grandparents served a protective role on zBMI for youth of Hispanic descent, except for the Cuban subgroup. There was no relationship between grandparent involvement and feeding and physical activity behaviors.

Conclusions

In some cases grandparents may serve a protective function for childhood obesity. These results highlight the need for future research on grandparents and children's health, especially among Hispanic subgroups.

Keywords: grandparents, obesity, Hispanic, children, caretaking

Introduction

Recent estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, Lamb, & Flegal, 2010) indicate that approximately one third of children in the United States are overweight, with 17% meeting criteria for obesity as measured by a Body Mass Index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012). Obesity results in a significantly elevated risk for adverse health outcomes including asthma, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer (Croyle, 2009). Children of Hispanic descent are at an increased risk for obesity (Kumanyika & Grier, 2006).

One cultural factor which may affect the rate of obesity in Hispanic children is the perception of “bigger” being healthier (Baylor, 2005; Crawford et al., 2004). For example, one study of Hispanic women found that although mothers preferred a slim figure type for themselves, they preferred a plump figure type for their children (Contento, Basch, & Zybert, 2003). When shown a series of photographs of young children, a group of Hispanic mothers agreed that the photo of the moderately overweight child was the healthiest (Crawford et al., 2004). Due to this cultural perception it has been suggested that nutrition education efforts with Hispanics should be focused on identifying positive eating behaviors rather than the child's weight status (Crawford et al., 2004).

In addition to the perception that bigger is better, in the Hispanic culture, “familismo” (identifying and being loyal to extended family members) is a traditional value many families uphold and has been identified as an important aspect to consider in adherence to treatment (Antshel, 2002). For instance, grandparents play an important role in Hispanic families and many grandmothers are responsible for caring for their grandchildren after school and for food preparation while parents work. Grandmothers are highly regarded in the Hispanic community and have been suggested as an important group to include in educational efforts (Palmeri, Auld, Taylor, Kendall, & Anderson, 1998).

There is a dearth of studies on the influence of grandparents on children's health. Recently, Pearce and colleagues (2010) reported on a cohort of 12,354 children from the United Kingdom. The results indicated that higher SES families who used informal childcare (75% of whom were cared for by grandparents) were more likely to have children who met criteria for obesity than those families who had their child in a formal childcare center. One epidemiological study of 2591 youth reported that among youth of normal weight parents grandparental obesity was positively associated with children's overweight status compared to children of normal weight grandparents (Davis et al., 2008). Childhood overweight status was associated with grandparent overweight status in a sample of 88 African American and Native-Americans (Polley et al., 2005). Other researchers have found negative associations between grandparent involvement and children's healthy eating habits (Jingxiong et al, 2007; Pearce et al., 2010, Roberts & Pettigrew, 2010). There is also some evidence to support the influence of grandparents’ feeding perspectives on Hispanic mother's feeding habits. For example, Baughcum and colleagues (1998) conducted a focus group study with a sample of low SES Hispanic mothers. Mothers reported that at times they did not follow the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) guidelines and physician recommendations regarding feeding strategies for their infants and instead identified their own mothers as the primary source of knowledge for infant feeding strategies.

Overall, there have been a few researchers that have explored the influence of grandparents on children's health but no published studies on the perceived influence of grandparents on eating and physical activity of Hispanic children, despite the cultural significance of the grandparent group in this population. Thus, the purpose of this preliminary study was to estimate the percentage of grandparents’ involved in caretaking for grandchildren in Hispanic families, to describe parents’ perceptions of grandparents involvement, and to determine whether that involvement had a negative impact on the child's BMI. It was hypothesized that children who had a grandparent involved in caretaking would have higher rates of unhealthy eating, sedentary activity, and higher BMIs than those children who did not have a grandparent involved in caretaking.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 199 school aged children (M age = 7.79 years, SD = 1.72) recruited from an elementary school in Miami, FL. Fifty-three percent of these children were female and all were identified by their parent as Hispanic. About half of the sample was of Cuban descent (n = 101); the other half was comprised of South or Central American descent (n = 42), more than one Hispanic background (n = 38), another country of Spanish origin (e.g. Spain; n = 11), and Mexican or Puerto Rican descent (n = 5). Two children's parents did not report their child's ethnic group. Many parents (49%) reported an average household income before taxes of less than $20,000 with 18% reporting an average household income before taxes of $50,000 or more. See table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Description on Children who Participated in the Study

| Mean Age (SD) | 7.79 (1.72) |

| % Female | 53 |

| % Cuban | 51 |

| % South or Central American | 21 |

| % Puerto Rican or Mexican | 3 |

| % Other Spanish-speaking Country | 6 |

| % More than one Hispanic Ethnicity | 19 |

| Mean Number of Years Mother has Lived in US (SD) | 18.14 (11.50) |

| Mean Number of Years Father has Lived in US (SD) | 18.30 (11.38) |

| % Family Household Income over $50,000 | 18 |

| % Overweight | 27 |

| % Obese | 30 |

| % Grandparent Involved | 43 |

Procedures

This study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board. In order to participate in this study children needed to be between the ages of 5 and 12, of Hispanic descent, and not have a diagnosis of a medical condition that affected their eating habits (e.g., diabetes, cystic fibrosis were excluded). Parents were informed of the inclusion/exclusion criteria and self-determined whether the child was able to participate or not. All assessment forms were provided in Spanish and English.

All students at a local urban public elementary school (Kindergarten to fifth grade) were invited to participate in this study via a letter from their principal sent home to the parents. If parents were interested in participating in the study, they were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire (that included questions about caretaking for the child and grandparents’ involvement) and consent to having their child's weight and height measured. On average, 42% of students in each classroom returned the study flier and 23% per classroom agreed to participate. Research assistants visited each classroom and weighed and measured those children whose parents had returned the consent and questionnaire. Assent was obtained from children prior to being weighed and a small prize (a pencil) was given at the end of the assessment. Parents were asked to self-identify whether there was a grandparent involved in caretaking for the child.

Measures

Grandparent Involvement Questionnaire

This measure was created to assess demographic information and the degree of involvement in caretaking for children by grandparents. The questionnaire had 54 questions consisting of demographics, grandparent involvement in caretaking for the child, and feeding and physical activity practices. There were three composite scores: negative eating, sedentary activity, and level of disagreement between parent and grandparent. The negative eating composite included questions such as, “When caretaking for the child, how often does grandparent give the child sweets and/or sodas?” The sedentary activity composite included questions such as, “On average when child is with grandparent how much time is he/she in front of a screen (television, computer, videogame)?” The disagreement composite included questions such as, “How often do you and the child's grandparent disagree on the type of food the grandparent gives child?”

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Children were weighed and measured by trained research assistants before lunch and without shoes at school. The same stadiometer (Seca) and scale (Tanita) were used for all children in this sample, with measurements rounded to the nearest tenth. Gender, age, height, and weight were used to calculate BMI. Standardized BMI scores, a BMI z-score, were then created per child to allow for comparisons. Children were also classified as overweight (zBMI≥85th percentile and <95th percentile) or obese (zBMI≥ 95th percentile).

Statistical Analysis

The percent of children with grandparents involved in caretaking and the degree of grandparent involvement (number of hours per week) was calculated. Sample demographics were correlated with children's zBMI scores. T-tests and chi square tests were used to determine whether there were differences on zBMI between children who had grandparents involved and those who did not. The three composite scores from the Grandparent Involvement Measure were correlated with child's zBMI.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Forty-three percent of parents reported that there was a grandparent involved in their child's caretaking. The mean zBMI of the children in the sample was .94 (SD = 1.05). Children's zBMI scores did not differ as a function of age. Boys (M = 1.14) had significnatly higher zBMI scores than girls (M = .82), t(197) = −2.22, p =.03. Fifty-seven percent of children in the sample were overweight (BMI at the 85th percentile or above) and 30% were obese (BMI at the 95th percentile or above). Of those children who were overweight or obese, 38% of parents reported that there was a grandparent involved in caretaking. Children's zBMI was not associated with mother, father, or grandparent number of years in the US.

Grandparent Involvement Related to Health Outcomes

Children who had a grandparent involved in caretaking did not have significantly different zBMI scores than those who did not have a grandparent involved in caretaking, t(197) = −.83, p =.NS. Degree of grandparent involvement was also not correlated with child's zBMI (r = −.01, p = NS), meaning that the amount of time a grandparent spent caring for a child was not associated with zBMI. Child's zBMI was positively associated with the parent report of disagreement composite (r = .28, p =.01): more disagreement between parent and grandparent was associated with higher zBMI scores in children. There was no association between zBMI and the other parent report composite scores (negative eating and sedentary activity). However, parent report of greater grandparent involvement was associated with higher negative eating (r = .26, p =.02). More disagreement between parents and grandparents (as reported by parents) was also associated with more negative eating (r = .27, p =.02) and more sedentary activity (r = .27, p =.02).

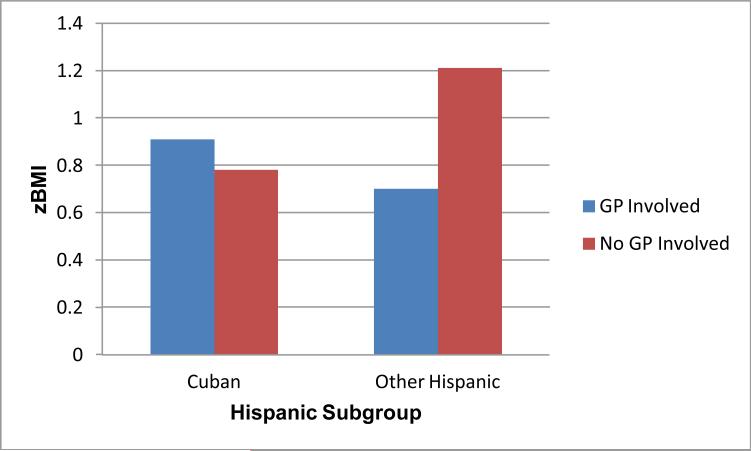

Follow-up ANOVA analyses were conducted to examine potential ethnic differences. Due to the large number of children from Cuban descent in the sample, the sample was divided into Cuban (n = 101) or other Hispanic origin (n = 98). There was a significant interaction between grandparent involvement status and ethnicity for zBMI, F(1, 195) = 4.46, p = .04. For children of Cuban descent zBMI did not differ for those who had a grandparent involved in caretaking (M = 1.00) and those who did not (M = .81). However, as shown in figure 1, for children from other Hispanic origin groups there was a significant relationship between zBMI and grandparent involvement status: those who had a grandparent involved in caretaking had lower zBMI (M = .79) than those who did not (M = 1.21).

Figure 1.

Interaction between grandparent involvement and ethnicity on child's zBMI

Discussion

Results from this study indicated that in a school aged sample of Hispanic children over half of the children were overweight and nearly a third met criteria for obesity, which is above national norms (Ogden et al, 2012). About half of the children in this sample had a grandparent involved in caretaking. Parent reported disagreement between themselves and their child's grandparent regarding feeding and physical activity of children emerged as the only significant predictor of children's weight. This aligns with previous research on the role of family discord and childhood obesity (Mendelson, White, & Schliecker 1995; Yannakoulia et al., 2008). It will be important to assess the role of concordance among caretakers in future studies. Contrary to our hypothesis, grandparent involvement did not have a negative impact on children's weight. Specifically, in non-Cuban Hispanics grandparent involvement had a positive influence on children's zBMI, but there was no relationship between grandparent involvement and weight for children of Cuban descent.

This protective finding was contrary to the hypothesis originally proposed for this study. Factors such as negative eating and sedentary activity under grandparent supervision, in addition to overall amount of time spent with grandparent caretakers were assessed to potentially explain the relationship. None of these factors were associated with the children's weight. Interestingly, parents’ perception regarding what grandparents are doing with their children (engaging in unhealthy eating habits) contradict the protective factor grandparents seem to be playing in regard to weight. One potential explanation for these findings is the level of adult supervision that children who are cared for by grandparents are receiving, versus those who are not cared for by grandparents. Even if parents believe the child is eating too much unhealthy food and engaging in too much sedentary activity when he/she is with a grandparent, those levels could be higher still if that child were home alone (Klesges, Stein, Eck, Isbell, & Klesges, 1991).

The results for the subsample of children of Cuban descent, which did not have a relationship between grandparent involvement and child weight, are more difficult to interpret. Interpreting these findings is difficult due to the paucity of research on both grandparents’ role in childhood obesity and differences among Hispanic ethnic groups. There are also potential mediating variables such as level of acculturation that need to be explored. Perhaps the most important message from these initial findings is that Hispanic subgroups may differ in their attitudes and behaviors regarding eating and physical activity for children and grouping all Hispanics into one category can lead to inaccurate interpretations of findings. Thus, future research should incorporate Hispanics from various ethnic groups to look at between group differences and consider variables such as level of acculturation and/or parental health perceptions and beliefs that may help explain differential findings.

Limitations of this study must be acknowledged. The response rate for this study represented only about a quarter of the school population and was skewed to younger children. The data were collected via a self-report measure that was sent home, versus collected in person, so less than ideal response environments were possible. No objective parent data, such as BMI, were available. The study used a cross-sectional design which makes conclusions regarding directionality of findings difficult. Lastly, the study focused on biological grandparents other caregivers serving as ‘functional’ versus genetic grandparents could also be included in future studies.

Although this study included the major influences on children's weight (dietary habits and physical activity), other potential influential variables were not assessed such as maternal weight, genetic influences or acculturation. A more thorough assessment of these influences on children's weight should be included in future research. For example, it would be especially interesting to include specific cultural values such as “familismo” and the “bigger is healthier” perception as potential mediators in the role of grandparents and children's weight status.

Overall, the purpose of this study was to explore the role of grandparents (who play an important role in caretaking for children within Hispanic families) as caregivers and if this involvement negatively impacted children's diet, physical activity, and weight. Although findings were not in the direction initially proposed, these results highlight the importance of further exploring the effect of extended family caregivers on children's health, especially in the Hispanic community. In fact, the protective role that grandparents play in some children's health will be important to further assess and the use of grandparents in interventions for weight management should be considered.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grant #5T32 HD07510 and 1R01HL102130. The authors would like to acknowledge the pediatric health behavior research team at the University of Miami study for their time and dedication to this project specifically, Erica Barrios, Heather Dehaan, Johannie Llanos, Sarah Martinez and Tarah Rogowski Martos. We also would like to thank all the children and families who participated, and the faculty and staff at Kensington Park Elementary for graciously allowing us to conduct research at their school.

References

- Antshel KM. Integrating culture as a means of improving treatment adherence in the Latino population. Psychology Health and Medicine. 2002;7(4):435–449. [Google Scholar]

- Baylor College of Medicine Special populations: Hispanic/ Latino American. Baylor College of Medicine. 2005 Oct 30; Retrieved from http://www.bcm.edu/mpc/special-hl.html.

- Baughcum AE, Burklow KA, Deeks CM, Powers SW, Whitaker RC. Maternal feeding practices and childhood obesity: a focus group study of low-income mothers. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1998;152:1010–1014. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.10.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contento IR, Basch C, Zybert P. Body image, weight, and food choices of Latina women and their young children. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2003;35(5):236–248. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford PB, Gosliner W, Anderson C, Strode P, Becerra-Jones Y, Ritchie LD. Counseling Latina mothers of preschool children about weight issues: suggestions for a new framework. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104:387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croyle RT. [August 11, 2011];Collaborative Initiative Will Tackle Obesity among Youth. 2009 Mar 10; from http://www.cancer.gov/ncicancerbulletin/031009/page4.

- Davis MT, McGonagle K, Schoeni RF, Stafford F. Grandparental and parental obesity influences on children overweight: implications for primary care practice. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2008;21:549–554. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.06.070140. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.06.070140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jingxiong J, Rosenqvist U, Huishan W, Greiner T, Guangli L, Sarkadi A. Influence of grandparents on eating behaviors of young children in Chinese three-generation families. Appetite. 2007;48:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesges RC, Stein RJ, Eck LH, Isbell TR, Klesges LM. Parental influence on food selection in young children and its relationships to childhood obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1991;53:859–64. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.4.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S, Grier S. Targeting interventions for ethnic minority and low-income populations. The Future of Children. 2006;16(1):187–207. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson BK, White DR, Schliecker E. Adolescents’ weight, sex, and family functioning. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1995;17(1):73–79. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199501)17:1<73::aid-eat2260170110>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:242–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. NCHS data brief, no 82. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2012. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeri D, Auld GW, Taylor T, Kendall P, Anderson J. Multiple perspectives on nutrition education needs of low-income Hispanics. Journal of Community Health. 1998;23(4):301–316. doi: 10.1023/a:1018775522429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce A, Li L, Abbas J, Ferguson B, Graham H, Law C, the Millennium Cohort Study Child Health Group International Journal of Obesity. 2010;34:1160–1168. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polley DC, Spicer MT, Knight AP, Hartley BL. Intrafamilial correlates of overweight and obesity in African-American and Native-American grandparents , parents, and children in rural Oklahoma. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105:262–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.11.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M, Pettigrew S. The Influence of Grandparents on Children's Diets. Journal of Research for Consumers. 2010;18:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yannakoulia M, Papanikolaou K, Hatzopoulou I, Efstathiou E, Papoutsakis C, Dedoussis GV. Association between family divorce and children's BMI and meal patterns: the GENDAI Study. Obesity. 2008;16:1382–87. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]