The simple question in the title of this piece reflects the fundamental function of undergraduate medical education (UME). In the past century, the purpose of medical training has moved from readiness for independent medical practice to readiness for postgraduate training. This requires a new benchmark for the transition from UME.

The recent emphasis on competency-based postgraduate medical training, with its competency frameworks and Milestones initiative, shows a shift from what abilities physicians in general should possess to what medical specialists should possess. An increasing number of postgraduate programs have now started to link competencies to so-called entrustable professional activities (EPAs),1–4 core units of professional work identified as tasks or responsibilities to be entrusted to a trainee once sufficient competence has been reached.5,6

If postgraduate training prepares for unsupervised practice from the first day after training, for what does undergraduate training prepare? Much of undergraduate training is workplace-based and it is a logical thought to use the same reasoning: What responsibilities are expected of the physician in the workplace from the first day of residency? That is not the same question as “What grades must medical students have attained in their theoretical and practical exams?” Trusting residents to work with limited supervision (ie, not checking everything that is being done) is a deliberate decision that affects patient safety. An entrustment decision means taking a calculated risk that chances of future adverse events are minimized. Many documents during the past decades have attempted to describe what qualities or competencies physicians should possess at the end of undergraduate medical training.7–9 However, looking at what exactly residents are expected to do safely from the first day of training has not been the general method, although some have used this approach for graduate medical education.10

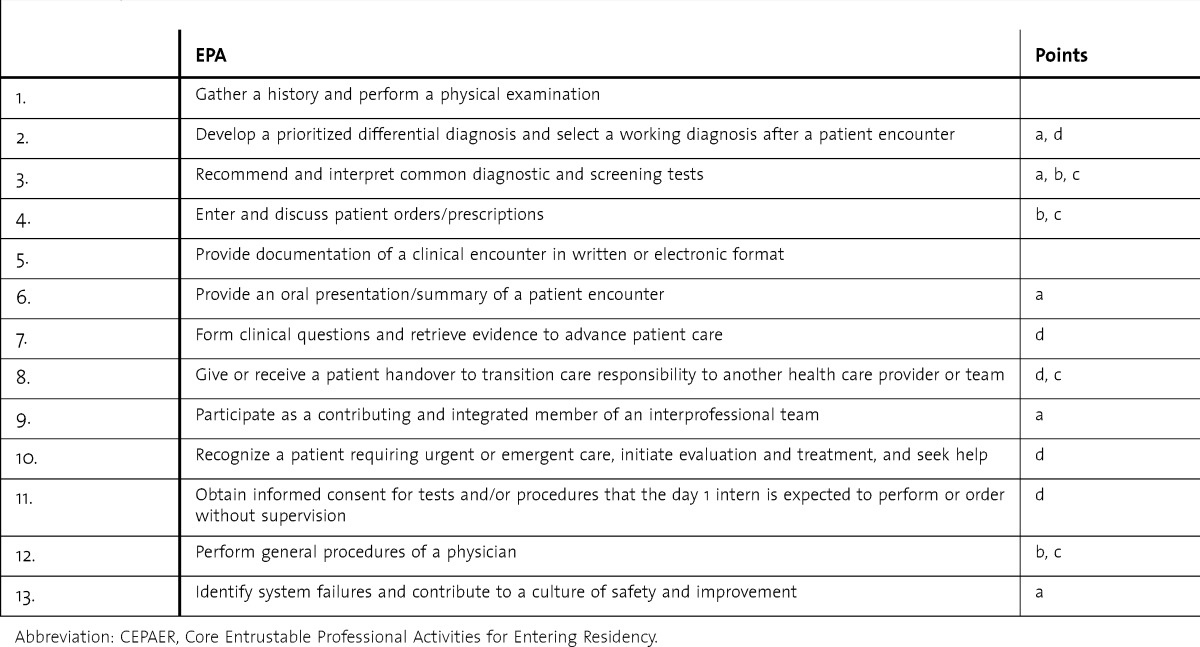

The Association of American Medical Colleges has produced a draft document called “Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency” (CEPAER), describing 13 EPAs that medical graduates should have attained at a level that permits practice without direct supervision (table).11 Medical trainees should be able to carry out these activities without direct supervision from the first day of residency. The authors are to be commended on this initiative for several reasons.

TABLE.

Proposed Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) for Undergraduate Medical Education in the CEPAER Report With Points of Attention

The first is its generalized nature. As the EPA concept, defined for postgraduate education, is now emerging in UME, schools may start defining these by themselves. However, a much better strategy is a concerted effort to define generalizable EPAs across schools, as a clear benchmark for any undergraduate and postgraduate program nationally and internationally. It is in fact a redefinition of what a medical physician is, in terms of what he or she should be able and allowed to do with limited supervision, following the meaning of competent in the sense of ability and right to act or judge.

Second, the number of EPAs is limited. Long lists of detailed activities tend to transform to checklists and lose power. It is a wise decision to focus on the most important and comprehensive acts medical students should be entitled to do with limited supervision by the end of training. A clear and concise set will be retained in the minds of learners and teachers on both sides of the graduation divide.

Third, defining core EPAs implies there is room for elective EPAs. Next to providing space for local differences in curricula, it also very much reflects the flexible competency-based nature of current training initiatives, which are moving from fixed time and flexible standards to fixed standards and flexible time.12 Trainees who have ambition, interest, and time available to add (speciality-) specific EPAs may be given the opportunity to do so.

The draft CEPAER document was presented in November 2013 with the aim to solicit feedback to enable the drafting of a final document in the spring of 2014. In this editorial I present a few specific and general observations that may help to further improve the document. I have witnessed institutions and groups designing EPAs that face similar issues, and hope this contribution can serve to inform a wider public. By the time this editorial is published, the CEPAER consortium may have crafted a next version of the document. Nevertheless, the current version may serve to draw some general lessons. I have distinguished 4 issues (a, b, c, d) and related them to each of the proposed EPAs (table).

a. Are All EPAs Really Stand-Alone EPAs?

EPAs should be designed to make clear what trainees are entitled to do with—for UME EPAs—indirect supervision only. EPAs are professional acts with a beginning and an end, and require specific knowledge and skills. Entrustment decisions to decrease the level of supervision are key in using EPAs for training. In addition, an EPA should be independently executable (eg, not be a necessary part of a bigger EPA). These notions should be helpful to determine whether the suggested EPAs can serve as such.

In applying the EPAs in the CEPAER document, it may be useful in some cases to consider splitting or rearranging some of them. Ordering diagnostic tests and writing prescriptions (EPA 4), for instance, may be such different things that they may justify 2 EPAs. Conversely, recommending diagnostic tests (EPA 3) may not be easily separable from ordering tests (EPA 4). Further, recommending tests (EPA 3) may not be a true EPA if it does not include a responsibility for patient care with only indirect supervision. A layperson or patient could also recommend a test, but only the responsibility to do this with only indirect supervision makes it an EPA. There should be a clear delineation between what the graduate may order with indirect supervision and what he or she may only recommend.

I also had some difficulty seeing EPAs 7, 9, and 13 as stand-alone activities (ie, as an act to be carried out with only indirect supervision). Rather, these appear to be important prerequisite skills for thoughtful patient care, probably as part of other specific EPAs.

EPA 10 would be an excellent stand-alone EPA if formulated as “initiating evaluation and treatment in patients requiring urgent or emergent care.” Of course the recognition part of this EPA is crucial, as well as acknowledging the need to seek help in most cases. This level of detail belongs to the description of the EPA rather than to its title.

b. Is Acting With Indirect Supervision Adequate for All of the EPAs?

It is important to make as clear as possible for all involved what privileges the graduate has in terms of the required level of supervision for EPAs. “Indirect supervision” is the focus of all 13 EPAs. This is defined as supervision that is away from the site of the patient encounter, but immediately available physically in the hospital or by telephone or other media. Not stated is whether indirect supervision means that a supervisor should check the work afterward, or a sample of it. For some EPAs, notably recommending and ordering tests (EPA 3 and EPA 4), prescribing medication (EPA 4), and performing procedures (EPA 12), I suggest that this must be specifically addressed.

c. What Are the Limitations of These EPAs?

The descriptions of most EPAs do not exactly reveal their scope. For instance, which are the “common tests” mentioned in EPA 3 or the “general procedures” in EPA 12? The same holds for EPA 4: Which tests, prescriptions, and therapies may the graduate order and which not? It is important for the sake of transparency to include listings of all relevant tests and procedures in the description of these EPAs. In many cases, explicit limitations may be added.

d. Sense and Simplicity

Sense & Simplicity was the 2005–2013 Dutch electronics manufacturer Philips' marketing slogan and was considered crucial to both consumers and manufacturing. Educational innovations too should make sense and be as simple as possible. Despite the complexity of education and many useful theories and operations that are not necessarily simplistic, the power of many innovations is greatly enhanced if they can be presented in simple and clear terms that resonate with teachers and can be remembered. This will also hold true for EPAs. I predict that further simplifying the CEPAER document and EPA descriptions will promote the sense it will make to clinical teachers. The title of an EPA should not be any longer than necessary. One example, “Obtain informed consent for tests and/or procedures that the day 1 intern is expected to perform or order without supervision” (EPA 11), could just as well be called “Obtain informed consent for tests and procedures,” as all UME EPAs are by definition acts that the intern is expected to perform on day 1 without direct supervision. Aligning language across EPAs would also serve simplicity, for example, “clinical encounter” (EPA 5) or “patient encounter” (EPA 6) don't need to be different words.

UME EPA titles could simply read as follows: standard history and physical examination (EPA 1); prioritized differential diagnosis following a patient encounter (EPA 2); ordering and prescribing tests and therapies (EPAs 3 and 4); documentation of clinical encounters in the patient's record (EPA 5); oral patient presentation (EPA 6); giving and receiving patient handovers (EPA 8); initiating evaluation and treatment in patients requiring urgent or emergent care (EPA 10); obtaining informed consent for tests and procedures (EPA 11); and general medical procedures (EPA 12). Naturally, for each of these EPAs it must be specified what is included and what are its limitations. Forming clinical questions, working interprofessionally, and contributing to patient safety may be part of important EPAs rather than EPAs in their own right.

Some General Observations

The EPA descriptions are lengthy. Following the approach used in the description of Milestones,13,14 the CEPAER report includes extensive descriptions of hypothetical behaviors of learners not yet ready for indirect supervision and those who are ready for independence, related to each EPA. While these descriptions are helpful for a developmental view of learners, including them with the necessary EPA description may distract readers and educators. My recommendations are to keep the EPAs short, clearly state what is included and what is not, and move most of the text under “description of the activity” to a rubric of Knowledge Skills and Attitude (or “curriculum”).6

Finally, a word about language. The authors of this document have extended the meaning of the word entrustable. In the EPA literature, the term has been used as an adjective that pertains to tasks or responsibilities that have the property of being entrusted to trainees or professionals. People themselves may be trustworthy, but not entrustable or pre-entrustable. I understand the strong tendency to replace trustworthy with entrustable, as being not trustworthy connotes dishonesty. Pre-entrustable may sound friendlier than not yet trustworthy. Trustworthiness, however, is more that honesty. Cambridge philosopher Onora O'Neill15 recently explained in a broadcasted Ted Talk that trustworthiness requires 3 features: competence, honesty, and reliability. Kennedy and colleagues16 found basically the same features for medical trainees: knowledge/skills, truthfulness, conscientiousness, and also discernment of limitations. Thus, even honest and reliable persons may not yet be trustworthy for an EPA. I'm not sure that pre-entrustable and entrustable are suitable adjectives for learners and behavior, as this usage may blur the meaning of the word entrustable as it is used currently. But the use of language evolves over time, and we cannot tell how this word will be used in the future. Entrustable learners and behavior may appear to be useful too.

With the CEPAER document the EPA concept has been drawn into an important new stage of application. The medical school graduate EPAs can truly be viewed as a key milestone toward a clear description of what is expected of medical professionals halfway through their training. May this editorial serve to further advance this critical initiative.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr Robert M. Englander for pointing him to Onora O'Neill's Ted Talk and for a constructive dialogue that led to adaptations in this editorial.

Footnotes

Olle ten Cate, PhD, is Professor of Medical Education at the Center for Research and Development of Education, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

References

- 1.Boyce P, Spratt C, Davies M, McEvoy P. Using entrustable professional activities to guide curriculum development in psychiatry training. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11:96. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaughnessy AF, Sparks J, Cohen-Osher M, Goodell KH, Sawin GL, Gravel J. Entrustable professional activities in family medicine. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):112–118. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00034.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauer KE, Kohlwes J, Cornett P, Hollander H, ten Cate O, Ranji SR, et al. Identifying entrustable professional activities in internal medicine training. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):54–59. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00060.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones MD, Jr, Rosenberg AA, Gilhooly JT, Carraccio CL. Perspective: competencies, outcomes, and controversy—linking professional activities to competencies to improve resident education and practice. Acad Med. 2011;86(2):161–165. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820442e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med Educ. 2005;39(12):1176–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):157–158. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson B. Learning objectives for medical student education—guidelines for medical schools: report I of the Medical School Objectives Project. Acad Med. 1999;74(1):13–18. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Herwaarden CL, Laan RF, Leunissen RR. The 2009 framework for undergraduate medical education in the Netherlands. Utrecht: 2009. http://www.nfu.nl/img/pdf/09.4072_Brochure_Raamplan_artsopleiding_-_Framework_for_Undergraduate_2009.pdf. Accessed January 1, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindgren S, editor. Basic Medical Education WFME Global Standards for Quality Improvement—the 2012 Revision. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Federation for Medical Education; 2012. pp. 1–46. http://www.wfme.org/standards/bme. Accessed January 1, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dijkstra IS, Pols J, Remmelts P, Bakker B, Mooij JJ, Borleffs JC, et al. What are we preparing them for: development of an inventory of tasks for medical, surgical and supportive specialties. Med Teach. 2013;35(4):e1068–e1077. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.733456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association of American Medical Colleges. Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency. Washington, DC: 2013:1–97. https://www.mededportal.org/icollaborative/resource/887. Accessed November 27, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank JR, Snell LS, ten Cate O, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638–645. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The Next GME Acreditation System—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swing SR, Beeson MS, Carraccio C, Coburn M, Iobst W, Selden N, et al. Educational milestone development in the first 7 specialties to enter the next accreditation system. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):98–106. doi: 10.4300/JGME-05-01-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onora O'Neill: What we don't understand about trust. http://www.ted.com/talks/onora_o_neill_what_we_don_t_understand_about_trust.html. Accessed November 16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy TJ, Regehr G, Baker GR, Lingard L. Point-of-care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med. 2008;83(suppl 10):89–92. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183c8b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]