Abstract

Despite substantial evidence for the fit of the three- and four-factor models of Psychopathy Checklist-based ratings of psychopathy in adult males and adolescents, evidence is less consistent in adolescent females. However, prior studies used samples much smaller than recommended for examining model fit. To address this issue, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis of 646 adolescent females to test the fit of the three- and four-factor models. We also investigated the fit of these models in more homogeneous subsets of the full sample to examine whether fit was invariant across geographical region and setting. Analyses indicated adequate fit for both models in the full sample and was generally acceptable for both models in North American and European subsamples and for participants in less restrictive (probation/detention/clinic) settings. However, in the incarcerated subsample, the four-factor model achieved acceptable fit on only two of four indices. Although model fit was not invariant across continent or setting, invariance could be achieved in most cases by simply allowing factor loadings on one PCL: YV item to vary across groups. In summary, in contrast to prior studies with small samples, current findings show that both the three- and four-factor models fit adequately in a large sample of adolescent females, and the factor loadings are largely similar for North American and European samples and for long-term incarcerated and shorter-term incarcerated/probation/clinic samples.

Keywords: adolescents, psychopathy, confirmatory factor analysis, antisocial behavior, sex differences

Models of the factor structure of psychological tests play a critical role in understanding and validating the constructs they are designed to assess. Scores on subsets of items for a measure that cohere similarly in diverse and independent samples provide evidence for the generalizability of the construct being measured. Evidence that a pattern of covariances is consistent with theoretical expectations makes an important contribution to construct validation (Strauss & Smith, 2009). Factor models that generalize across different kinds of samples provide a foundation for subsequent scientific studies that examine whether these dimensions are characterized by similar nomological networks across samples. Such studies, in turn, can be used to test hypotheses about the mechanisms underlying the components of a syndrome.

Psychopathy is a severe syndrome of personality pathology that is widely associated with callous and manipulative interpersonal behavior as well as impulsive and irresponsible antisocial behavior. The standard clinical measures of the psychopathy construct are the Hare Psychopathy Checklist (PCL) scales which ask raters to make inferences about underlying dispositions by integrating information from interviews, behavioral observations, and file or other collateral material (Hare & Neumann, 2009). These scales include the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R; Hare, 2003), the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL: SV; Hart, Cox, & Hare, 1995), and the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL: YV; Forth, Kosson, & Hare, 2003).

Several factor models of the PCL scales have been proposed. The four-factor model suggests that individual differences in the dispositions that comprise psychopathy are underlain by differences in one or more of four correlated dimensions that reflect specific interpersonal, affective, lifestyle, and antisocial features. Evidence corroborating this model comes from confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) of PCL scores in a variety of forensic, clinical, and community populations (e.g., Babiak, Neumann, & Hare, 2010; Hare & Neumann, 2008; Neumann & Hare, 2008). This pattern of strong correlations has been explained by a second-order general factor (Neumann, Hare, & Newman, 2007; Neumann, Kosson, Forth, & Hare, 2006) said to reflect the superordinate syndrome of psychopathic personality. This interpretation is consistent with behavior genetic research that has shown that four psychopathy factors similar to the PCL factors can all be accounted for by a common genetic trait (Larsson, Andershed, & Lichtenstein, 2006).

The three-factor model (Cooke & Michie, 2001) is identical with respect to the first three dimensions of the four-factor model but omits the antisocial features dimension (and the five items that load on that component).1 Because tests of both the three- and four-factor PCL models of psychopathy often yield acceptable fit in adult and adolescent males (Cauffman, Kimonis, Dmitrevia, & Monahan, 2009; Neumann, Hare & Newman, 2007; Neumann et al., 2006; Salekin, Brannen, Zalot, Leistico, & Neumann, 2006), these models are currently the dominant models for the internal structure of psychopathy based on clinical measures.2

In contrast, the fit of these factor models in female samples is more controversial. Among adult women, Warren et al. (2003) reported good fit for the two and three factor models. Similarly, Neumann et al. (2007) reported good fit for the four-factor model in both male and female adult inmates, whereas Salekin, Rogers, and Sewell (1997) suggested the factor structure is somewhat different in women than men. Bolt, Hare, Vitale, and Newman (2004) conducted item analyses in large samples of adult male and female offenders and reported that scalar equivalence may hold, at least approximately, for male and female offenders in spite of some evidence for differential test functioning and for differential item functioning on some lifestyle and antisocial dimension items.

Vitale and Newman (2001a) noted that most prior factor analytic studies have involved small samples that may have provided inadequate power for examining factor structure. They emphasized the need for researchers to conduct studies with larger samples of females. Examining adolescents, Forth et al. (2003) reported acceptable fit for the three-factor model in a sample of female adolescents, whereas the four-factor model achieved acceptable fit only on the absolute fit indices examined. However, their sample (based on six different subsamples) included only 147 girls. Consequently, analyses were likely underpowered for evaluating both models3. In addition, Forth et al. did not subdivide the sample to examine fit separately for incarcerated versus probation samples of girls or for samples from different parts of the world.

Subsequent studies have also yielded conflicting findings. Jones, Cauffman, Miller, and Mulvey (2006) reported reasonable fit for the three- and four-factor models in girls but only after making minor changes to the factor structures that have not been evaluated in other studies. In contrast, Sevecke, Pukrop, Kosson, and Krischer (2009) reported that neither the three-factor nor the four-factor model yielded generally acceptable fit among incarcerated German adolescent females. In an Item Response Theory analysis, Schrum and Salekin (2006) reported that some of the same items that are most discriminating in male samples were most discriminating in a sample of female youth. However, they noted that some items were more or less discriminating in girls than in boys. Despite a few recent studies the relative dearth of research in this area is of concern because of the potential differences in measurement structure and in the correlates of constructs which can occur across sex. Although prior studies provide some information about the factor structure of PCL: YV psychopathy in specific settings and locations, the small size of these samples is likely to work against obtaining good fit for both the three- and four-factor models.

The possibility of a different factor structure for girls than for boys is especially interesting in light of evidence that some of the correlates of scores (on clinical measures of psychopathy) in males do not consistently generalize to female samples. For example, associations between psychopathic traits and response modulation deficits (Vitale & Newman, 2001b; cf., Vitale, Brinkley, Hiatt, & Newman, 2007) and affective modulation of startle reflexes (Sutton, Vitale, & Newman, 2002) appear less consistent in adult female than male samples. Although some studies have yielded relatively similar patterns of correlations for psychopathy ratings in females and in males (Kennealy, Hicks, & Patrick, 2007; Stockdale, Olver, & Wong, 2010) or patterns of correlations in females similar to those previously reported for males (Bauer, Whitman, & Kosson, 2011; Penney & Moretti, 2007), other studies have cast doubt on the construct validity of PCL: YV scores among female adolescents (Odgers, Reppucci, & Moretti, 2005; Vincent, Odgers, McCormick, & Corrado, 2008).

It is important to keep in mind that all of the findings on the factor structure of psychopathy reviewed above are based on PCL measures of psychopathy. Factor analytic studies can only provide evidence on the structure of a construct as assessed using a specific measure. Even so, evidence that the factor structure differs for girls and boys when psychopathy is assessed with the PCL: YV would suggest the possibility that some of the differences in behavioral and physiological correlates of psychopathy ratings may reflect differences in the nature of the psychopathy construct in girls. In brief, evidence that the symptoms of psychopathy (as assessed by clinical measures) cohere differently for girls than boys would suggest that different features may be critical to the expression of psychopathy in girls and would increases the plausibility of the perspective that different mechanisms may account for the appearance of these symptom dimensions.

In contrast, evidence for a similar underlying factor structure would suggest that a psychopathy measure is performing similarly in boys and girls. To the extent that the symptoms examined cohere in similar ways across sex, it becomes more likely that a pattern of similar correlations between psychopathy ratings and external criteria reflects similar underlying mechanisms. Although evidence for similarity in internal structure does not invalidate the differences reported in correlational studies, it would be consistent with the possibility that similar mechanisms may account for those relationships between psychopathy and external criteria that are similar in males and females4.

As noted above, one of the chief limitations of prior factor analytic investigations in females has been the use of small samples. Small samples can lead to poor fit even though the fit might be quite good when examined within large enough samples. Another limitation of prior studies is that none of the above mentioned studies compared factor models across youth in different countries or continents, and no prior studies have compared the fit of the different models in different kinds of settings.

The Current Study

The primary goal of the present study was to test the factor structure underlying PCL: YV-based psychopathy in a large sample of adolescent females. We assembled data from a large number of prior published studies that used the PCL: YV with adolescent girls. This provided us with a relatively large dataset of 776 adolescent females (646 with no missing values). In examining this large sample, we hoped to provide greater clarity on the factor structure of psychopathy in adolescent females.

A secondary goal of this study was to evaluate the fit of the best-fitting models in more homogeneous subgroups of participants and to assess whether the models demonstrated invariance for subsamples of participants assessed in different continents and participants assessed in different settings. We conducted both separate confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) for North American and European subsamples as well as multiple-group CFAs to evaluate whether the models provided good explanations for the pattern of item-to-factor relationships in samples in different continents; we conducted a parallel set of separate CFAs and multiple-group CFAS to address the same issues for incarcerated adolescent females versus those in less restrictive settings, including probation and short-term detention/evaluation centers.

We realized that there are important cultural differences between the different countries within North America and within Europe. However, an analysis of factor loadings in North American versus European samples provides an initial examination of whether the factor models are characterized by structural invariance across geographic region. Similarly, because youth who commit more frequent and more serious crimes and perform poorly under conditional release are likely to be sent to more restrictive settings, it is likely such settings will include a higher proportion of youth with many psychopathic features. Consequently, an analysis of the fit of the models for incarcerated adolescents versus adolescents in less restrictive (short-term detention, community probation, and clinic) settings provides a preliminary assessment of invariance across setting.

Method

Participants

Data on 776 adolescent females were made available to the authors. These participants had participated in 14 different studies with independent samples; findings for a combination of the data from five of these samples were previously reported in the PCL: YV Technical Manual (Forth et al., 2003). Basic descriptive information about the participants from each sample is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants.

| Samples in the PCL: YV Manual | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | N | Setting | Country | Method |

| 1. Lewis and O'Shaughnessy (1998) | 37 | arrested/inpatient (I) | Canada (NA) | S |

| 2. Gretton and Hare (2002) | 43 | arrested/inpatient (I) | Canada (NA) | F |

| 3. Rowe (2002) | 54 | high risk probation (D) | Canada (NA) | F |

| 4. Bauer, Whitman, and Kosson (in press) | 80 | incarcerated (I) | United States (NA) | S |

| 5. Indoe (2002) | 28 | incarcerated (I) | United Kingdom (E) | S |

| Additional Samples | ||||

| 6. Kosson et al. (2011) | 21 | detention center (D) | United States (NA) | S |

| 7. Salekin, Leistico, Trobst, Schrum, & Lochman (2005) | 45 | detention center (D) | United States (NA) | S |

| 8. Salekin, Neumann, Leistico, & Zalot (2004) | 38 | detention center (D) | United States (NA) | S |

| 9. Salekin, Neumann, Leistico, DiCicco, & Duros (2004) | 37 | court evaluation (D) | United States (NA) | S |

| 10. Schmidt, McKinnon, Chattha, and Brownlee (2006) | 49 | court evaluation (D) | Canada (NA) | F |

| 11. Krischer and Sevecke (2008) | 171 | incarcerated (I) | Germany(E) | S |

| 12. Fowler et al. (2009) | 11 | psychiatry/ped clinic (D) | United Kingdom(E) | S |

| 13. Andershed, Hodgins, & Tengström (2007) | 99 | substance misuse clinic (D) | Sweden (E) | S |

| 14. Das, de Ruiter, & Doreleijers (2008) | 67 | secure treatment facility (I) | Netherlands (E) | S |

|

| ||||

| Incarcerated | 369 Samples 1, 2, 4, 5, 11, 14 | |||

| Probation | 277 Samples 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13 | |||

| North American | 285 Samples 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 | |||

| European | 361 Samples 5, 11, 12, 13, 14 | |||

Note. I = incarcerated; D = detention center/ probation / clinic. NA= North America; E = Europe. S = standard method (interview + collateral); F = file only. method. All of the samples listed were collected independently

Measure

Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL: YV)

The PCL: YV is a multi-item rating scale that assesses interpersonal and affective characteristics as well as overt behaviors associated with psychopathy. The measure is designed to be completed by trained observers who rate the presence of each trait disposition on the basis of a semi-structured interview and a review of case history information or other collateral source(s). Ratings based on both interview and collateral data are described as obtained using the standard assessment method. The PCL: YV manual also permits the use of files only to complete the instrument but suggests caution in interpreting file-only scores, as the file-only method commonly provides substantially less information for scoring several of the interpersonal and affective items. Even so, prior factor analytic studies indicate acceptable fit for both PCL-R scores and PCL: YV scores completed solely on the basis of institutional files (Bolt et al., 2004; Forth et al., 2003). Scores of 0 (consistently absent), 1 (inconsistent), or 2 (consistently present) for each item of the PCL: YV reflect inferences about the consistency of the specific tendency or disposition across different situations and sources of information.

Scores on the PCL: YV have demonstrated internal consistency, with alpha coefficients ranging from .79 to .94 for total scores and mean inter-item correlations ranging from .44 to .63 (Forth et al., 2003; Vitacco, Neumann, & Caldwell, 2010). Alphas for factor scores have ranged from 68 to .77 in the validation sample (Forth et al., 2003) and from .50 to .82 in smaller samples (Andershed, Hodgins, & Tengström, 2007; Vitacco, Neumann, Caldwell, Leistico, & Van Rybroek, 2006; Vitacco et al., 2010) with one exception (Skeem & Cauffman, 2003). Lower alphas for factor scores are expected in light of the number of items that contribute to each factor. Researchers have obtained good to excellent inter-rater reliability for total scores (ICCs range from .82 to .98; see Andershed et al., 2007; Cauffman et al., 2009; Das, de Ruiter, Doreleijers, & Hillege, 2009; Forth et al., 2003). The inter-rater reliability for factor scores is more variable, ranging from .43 to .86 (Forth et al., 2003; Skeem & Cauffman, 2003). PCL: YV scores correlate moderately with indices of externalizing psychopathology, instrumental violence, criminal activity, and antisocial behavior, and predict recidivism in male adolescents (Flight & Forth, 2007; Kosson et al., 2002; Kubak & Salekin, 2009; Murrie, Cornell, Kaplan, McConville, & Levy-Elkon, 2004; Salekin, 2008; Salekin, Neumann, Leistico, DiCicco, & Duros, 2004; Schmidt, McKinnon, Chattha, & Brownlee, 2006; Vitacco et al., 2006, 2010).

Data Analysis

Confirmatory factor analyses test the fit of specific models for the latent structure underlying variation on observed indicators. Such analyses require that investigators first specify the number of latent factors, the relationships between indicators and factors, and the factor variances and covariances within a model and then statistically test the adequacy of their model in terms of standard model fit criteria. To test alternative latent structures of the PCL: YV, we carried out CFAs with Mplus Version 5 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007), using the robust (mean- and variance-adjusted) weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimator recommended for use with ordinal data such as PCL: YV items (Flora & Curran, 2004; Neumann, Kosson, & Salekin, 2007).

Because each fit index has limitations and there are no agreed upon methods for definitively determining quality of fit (Kline, 1998), adequacy of fit for each model was estimated using several measures. Because the chi-square is usually significant with large samples, investigators typically rely on other fit indices to assess the adequacy of a model. We calculated two widely validated relative fit indices: the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). The TLI and the CFI are incremental fit measures comparing the estimated model with a null or independence model; the TLI tends to be more adversely affected by the estimation of additional parameters that do not improve model fit and is less sensitive to sample size than many other relative fit indices (Marsh, Balla, & McDonald, 1988). For these indices, larger values indicate better fit of the hypothesized model (a conventional standard is 0.9 or above for acceptable fit, 0.95 or above for excellent fit; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 1998).

We also examined two absolute fit indices: the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Absolute indices gauge how well the model-generated covariance matrix reproduces the sample covariance matrix. Smaller absolute fit indices, and thus smaller residual error values, indicate better fit. The RMSEA is an index that also rewards model parsimony (Brown, 2006), whereas the SRMR appears to be an especially sensitive indicator of poor fit. Moreover, because the SRMR and RMSEA provide relatively different approaches to estimating absolute fit, they provide somewhat more independent assessments of fit than some indices (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For these indices, Hu and Bentler (1999) suggested that scores below .05 indicate good fit, whereas scores between .05 and .08 indicate acceptable fit and values above 1.0 indicate poor fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hoyle, 1995; Marsh, Hau, & Wen, 2004; MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996).

An important caveat to the use of multiple fit indices is that, as model complexity increases, so does the size of the sample needed to test the model and the difficulty of achieving conventional levels of model fit (Marsh et al., 2004). Put another way, if a more complex model displays approximately similar fit to a less-complex model, then the former is said to have survived a riskier test (Vitacco, Neumann, & Jackson, 2005; Vitacco, Rogers, Neumann, Harrison, & Vincent, 2005). However, given the adequate size of our full sample for all models examined, models were considered to fit adequately only if they indicated at least fair to acceptable fit on all four primary fit indices examined. Because the subsamples were only about half as large as the full sample from which they were drawn, we required at least fair to acceptable fit on three or more fit indices to indicate acceptable fit for sub-sample analyses.

As in most recent tests of the three-factor model, we did not test the original three-factor model that uses testlets because prior studies conducted in several samples have shown that the model with testlets results in untenable solutions with impossible values (i.e., negative variance; Kosson et al., 2002; Salekin et al., 2006). For this reason, we examined a three-factor model without testlets (i.e., allowing the latent variables to load directly onto the PCL: YV items). It is this three-factor model that has achieved good fit in prior CFAs of adolescents (e.g., Neumann et al., 2006; Sevecke et al., 2009). Because the three-factor model is based on a different set of items and therefore a different covariance matrix than is the four-factor model, direct statistical comparison of these models is not possible (Brown, 2006; Kline, 1998).

From a mathematical modeling perspective, the three-factor model is less parsimonious than the four-factor model because it requires estimating 29 parameters to model 91 data points (df = 91 − 29 = 62), whereas the four-factor model uses only 42 free parameters to explain 171 data points (df = 171 − 42 = 129). However, this study was not designed to examine the relative merits of these two factor models but to examine their fit in a large sample of adolescent females and to examine whether there was evidence for invariance of these two models across different settings and for samples from Europe versus North America. Moreover, because the three-factor model is contained within the four-factor model, the two models are quite similar in most respects. The chief difference between the models concerns the nature of the antisocial dimension of the psychopathy construct (and the five items that load on this latent factor; this issue is addressed elsewhere, e.g., Hare & Neumann, 2008, 2010; Cooke, Michie, Hart, & Clark, 2004).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Principal analyses were based on participants with complete data. To ensure that the same participants were included in three-factor and four-factor analyses, only participants with complete data for the 18 items needed for the four-factor analyses were included in these analyses. Complete data for the 18 items were available for 646 adolescent females (369 incarcerated females and 277 females drawn from less restrictive settings (probation, detention centers, and clinics).

Supplementary analyses were also conducted including cases containing missing values. These analyses included 776 adolescent females (423 incarcerated and 353 probation/detention/clinic adolescents). To test the assumption of full information CFAs that missing data were missing at random (i.e., that there are no systematic reasons why some items were not scored for some participants), we first conducted analyses to ascertain whether missing data covaried with differences on demographic variables. Chi square analyses revealed that missing values were more prevalent in North American than in European datasets, χ2 (1) = 94.35, p < .001, and were more prevalent among incarcerated youth than among youth in less restrictive settings, χ2 (1) = 10.60, p = .001. Missingness was also much more likely for file-only than for standard (interview plus file) data, χ2 (1) = 37.56, p < .001. Although ethnicity was only available for 342 cases, missing values were also more prevalent among Caucasian and Native North American adolescents than among African or Latina adolescents, χ2 (3) = 87.22, p < .001,. Based on these analyses, we focus on analyses for samples including no missing values5.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses of the PCL: YV in the Full Sample of Female Adolescents

We first examined the fit of the various factor models in the full sample. The one-factor and two-factor models were examined using the same 18 items as in the four-factor model. The CFA for the one-factor model indicated unacceptable fit for two of the four primary fit indices examined, χ2 (78) = 699.37, p < .001, CFI = .80, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .111, SRMR = .087. The CFA for the two-factor model also indicated unacceptable fit for the CFI and only fair to acceptable fit for the RMSEA, with adequate fit on the other two indices examined, χ2 (79) = 498.36, p < .001, CFI = .86, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .091, SRMR = .074.

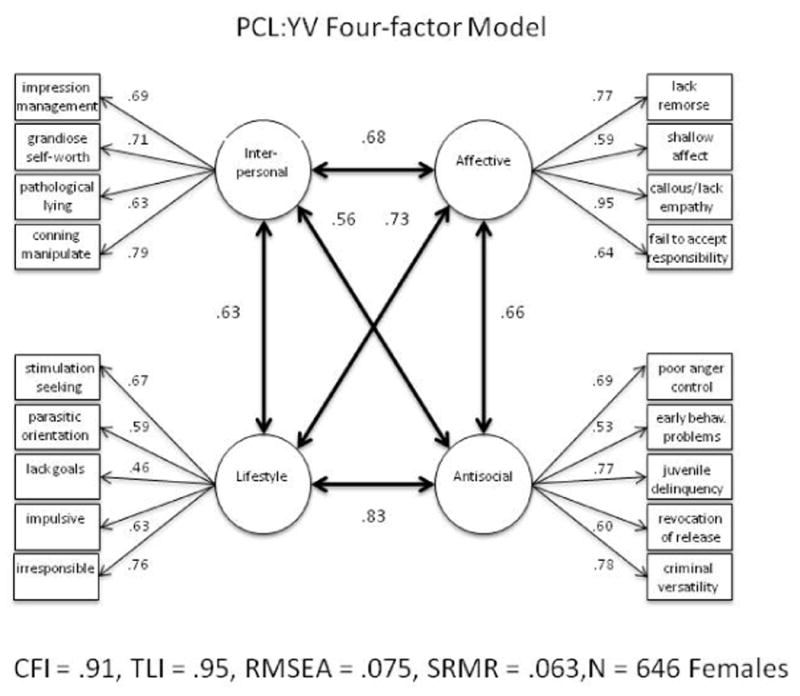

In contrast, both the three-factor and four-factor model yielded adequate fit for both relative fit indices and for both absolute fit indices. Figure 1 displays the standardized parameters for these two models. The CFA results for the three- and four-factor models for the full sample and each of the subsamples are shown in Table 2. The CFAs also showed that the factors were correlated as expected. The latent correlations between the interpersonal and the affective, lifestyle, and antisocial dimensions were .68, .63, and .56; the correlations between the affective and lifestyle and antisocial dimensions were .73 and .66, and between the lifestyle and antisocial dimensions was .83.

Figure 1.

Factor loadings, factor covariances, and fit indices for the four-factor model, full sample analysis in adolescent females (N = 646).

Table 2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model Fit Results.

| Model/Fit Index | Full Sample (n = 646) |

Restrictive Setting (n = 369) |

Less Restrictive Setting (n = 277) |

North American Adolescents (n = 285) |

European Adolescents (n = 361) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three-factor | |||||

| χ2 (df) | 219.87 (45) | 133.573 (42) | 117.612 (37) | 86.264 (40) | 128.401 (40) |

| CFI | 0.922 | 0.897 | 0.922 | 0.956 | 0.925 |

| TLI | 0.955 | 0.921 | 0.956 | 0.978 | 0.947 |

| RMSEA | 0.078 | 0.077 | 0.089 | 0.064 | 0.078 |

| SRMR | 0.060 | 0.072 | 0.073 | 0.058 | 0.069 |

| Four-factor | |||||

| χ2 (df) | 367.64 (79) | 270.719 (68) | 196.994 (61) | 146.633 (70) | 254.718 (63) |

| CFI | 0.906 | 0.825 | 0.909 | 0.942 | 0.890 |

| TLI | 0.952 | 0.874 | 0.949 | 0.974 | 0.930 |

| RMSEA | 0.075 | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.062 | 0.092 |

| SRMR | 0.063 | 0.087 | 0.080 | 0.063 | 0.083 |

Note. CFI = Comparative Fit Index ( > .90); TLI = Tucker–Lewis Index ( > .90); RMSEA =Root Mean Square Error of Approximation ( < .10); SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual ( < .10). Values considered at least fair to acceptable are shown in boldface type; cutoffs for values indicating at least fair to acceptable fit are listed in parentheses in this note. In this table, restrictive setting refers to youth facilities providing long-term incarceration, whereas less restrictive settings include probation, short-term detention, and clinic settings.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses of the PCL: YV in Subsamples of Female Adolescents

Both models also yielded consistently adequate fit in the North American subsample. In fact, model fit was in the good to excellent range for both of the relative fit indices and in the reasonable range for both absolute fit indices for both models despite a substantial drop in sample size from 646 to 285 cases (which makes the size of the subsamples sub-optimal for assessing the fit of the four-factor model). In contrast, only the three-factor model yielded consistently acceptable fit in the European subsample. The fit of the four-factor model was in the fair to acceptable range for three of four indices examined but slipped barely below acceptable levels for the CFI.

Both models also yielded generally acceptable fit for the subsample of youth in less restrictive (i.e., probation, detention, and clinic) settings. In brief, the fit was acceptable to good for both models for both measures of relative fit and for the SRMR. However, the RMSEA yielded only fair fit for both models in this subsample. In contrast, only the three-factor model yielded generally acceptable fit for the subsample of incarcerated girls. Only the CFI slipped below acceptable levels for this model. For the four-factor model, both relative fit indices were unacceptably low, and both indices of absolute fit indicated only fair fit.

In summary, both the three- and four-factor models had good fit to the data (i.e., were able to reproduce the observed item covariance structure with adequate precision) in the full sample, and both models provided reasonable fit among North American girls. Even among European girls, both models generally provided at least fair to reasonable fit. Similarly, with the exception of the RMSEA, both models provided adequate levels of fit among girls on probation and in detention. The only subsample in which the pattern of findings suggested fit below conventional levels of acceptability was the incarcerated subsample, for which the four-factor model yielded unacceptable fit on two indices and only fair to acceptable it on the other two indices examined.

Tests of Model Invariance between North American and European Samples

To test whether the three-factor model fit equally well in North American and European adolescent females, we conducted two multiple group CFAs (MGCFAs) and compared the fit for the two models using a chi-square difference test. First, we allowed Mplus to freely estimate all model parameters separately by sample (i.e., factor loadings and item thresholds), fixing scale factor values at 1.0, factor means at 0, and factor variances at 1 as is the default in Mplus in multi-group analyses when using the default delta parameterization. Under these conditions, the model yielded evidence of acceptable fit on all three indices other than the chi-square, χ2 (80, N =646) = 216.89, p < .001, CFI = 0.938, TLI = 0.964, RMSEA = 0.073. Next, we repeated the analysis constraining the loadings (but not the thresholds) to be equal in the two groups. This model yielded similar evidence of good fit across the two subsamples on relative fit indices and acceptable fit on an absolute fit index, χ2 (78, N =646) = 289.82, p < .001, CFI = 0.941, TLI = 0.963, RMSEA = 0.074. However, the model yielded poorer fit than the less constrained model, as evidenced by a significant chi-square difference test, χ2 (9) = 26.65, p = .002. To examine whether the lack of invariance could be attributable to a single item loading differently, we re-conducted the MGCFA allowing different loadings on PCL: YV Item 9, Parasitic Orientation, the item for which the multi-group CFA estimating the loadings separately had suggested the most disparity in item loadings (See Table 3). This analysis yielded a non-significant chi-square difference test, χ2 (8) = 13.16, p = .11. In sum, the generally reasonable fit for the three-factor model with constraints on the loadings in the two samples provides evidence of structural invariance. Moreover, it was possible to obtain evidence of structural invariance as indicated by good fit for a model requiring equal loadings on 12 of the 13 item indicators across the North American and European subsamples.

Table 3. Factor Loadings and Thresholds for the Four-Factor Model in Multi-Group Analyses in which Item Loadings are Estimated Separately in Different Subsamples.

| Factor | Restrictive Setting (n = 369) | Less Restrictive Setting (n = 277) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loadings | b1 | b2 | Loadings | b1 | b2 | ||

| Interpersonal | Item 1 | .59 | -0.49 | 0.69 | .67 | 0.39 | 0.08 |

| Item 2 | .68 | -0.31 | 0.86 | .70 | 0.30 | 1.26 | |

| Item 4 | .71 | -0.72 | 0.78 | .58 | -0.41 | 1.14 | |

| Item 5 | .61 | -0.98 | 0.38 | .86 | -0.14 | 1.08 | |

| Affective | Item 6 | .79 | -0.85 | 0.23 | .81 | -0.58 | 0.59 |

| Item 7 | .60 | -0.08 | 0.90 | .58 | 0.20 | 1.46 | |

| Item 8 | .91 | -0.90 | 0.33 | .92 | -0.14 | 1.06 | |

| Item 16 | .52 | -0.96 | 0.42 | .73 | -0.33 | 0.68 | |

| Lifestyle | Item 3 | .57 | -1.51 | -0.02 | .62 | -0.69 | 0.80 |

| Item 9 | .55 | -0.43 | 1.00 | .56 | 0.20 | 1.49 | |

| Item 13 | .37 | -0.56 | 0.53 | .66 | -0.39 | 0.47 | |

| Item 14 | .59 | -1.38 | -0.03 | .71 | -1.43 | 0.42 | |

| Item 15 | .64 | -1.45 | -0.05 | .83 | -0.69 | 0.53 | |

| Antisocial | Item 10 | .78 | -1.11 | -0.17 | .58 | -0.93 | 0.45 |

| Item 12 | .33 | -0.11 | 0.55 | .61 | 0.53 | 1.28 | |

| Item 18 | .68 | -1.11 | -0.06 | .83 | -0.59 | 0.82 | |

| Item 19 | .46 | -0.51 | 0.45 | .63 | 0.30 | 1.11 | |

| Item 20 | .79 | -0.41 | 0.40 | .79 | 0.04 | 0.91 | |

| Interpersonal | Item 1 | .76 | 0.00 | 1.02 | .65 | -0.20 | 0.87 |

| Item 2 | .77 | -0.05 | 0.85 | .62 | -0.05 | 1.15 | |

| Item 4 | .72 | -0.61 | 0.70 | .50 | -0.56 | 1.14 | |

| Item 5 | .85 | -0.30 | 0.81 | .82 | -0.82 | 0.52 | |

| Affective | Item 6 | .78 | -0.91 | 0.24 | .76 | -0.60 | 0.50 |

| Item 7 | .63 | -0.14 | 0.92 | .53 | 0.18 | 1.23 | |

| Item 8 | .91 | -0.67 | 0.53 | .99 | -0.44 | 0.66 | |

| Item 16 | .58 | -0.87 | 0.31 | .67 | -0.51 | 0.71 | |

| Lifestyle | Item 3 | .75 | -0.82 | 0.35 | .68 | -1.33 | 0.27 |

| Item 9 | .74 | -0.10 | 1.14 | .48 | -0.20 | 1.19 | |

| Item 13 | .43 | -0.75 | 0.36 | .46 | -0.30 | 0.63 | |

| Item 14 | .62 | -1.56 | 0.09 | .63 | -1.30 | 0.21 | |

| Item 15 | .67 | -1.27 | 0.00 | .83 | -0.91 | 0.34 | |

| Antisocial | Item 10 | .57 | -1.11 | -0.05 | .76 | -0.97 | 0.21 |

| Item 12 | .55 | 0.26 | 1.00 | .57 | 0.07 | 0.68 | |

| Item 18 | .68 | -1.65 | 0.18 | .84 | -0.50 | 0.37 | |

| Item 19 | .60 | -0.57 | 0.23 | .57 | 0.15 | 1.21 | |

| Item 20 | .66 | -0.47 | 0.60 | .86 | -0.02 | 0.60 | |

NOTE. b1 = Threshold 1; b2 = Threshold 2. In this table, restrictive setting refers to youth facilities providing long-term incarceration, whereas less restrictive settings include probation, short-term detention, and clinic settings.

We also examined whether the four-factor model fit equally well in the North American and European samples. Again, the unconstrained model yielded evidence of acceptable fit on all indices, χ2 (132, N =646) = 411.24, p < .001, CFI = 0.908, TLI = 0.950, RMSEA = 0.081. Once again, the model constrained to have equal loadings (but not thresholds) also yielded acceptable fit on both relative and absolute fit indices, χ2 (117) = 362.15, p < .001, CFI = 0.919, TLI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.081. However, as for the three-factor model, the chi-square difference test indicated poorer fit for the constrained model, χ2 (13) = 39.16, p < .001. As above, we examined whether we could achieve structural invariance on all but one item by allowing the loadings to vary for one indicator. Once again, the MGCFA suggested the most disparate loadings were for PCL: YV Item 9. In this case, the multi-group CFA allowing separate thresholds in the two samples but equal loadings (except on Item 9) yielded a chi-square difference test that was still significant, χ2 (12) = 23.19, p = .03. Similarly, allowing different loadings on two items (Items 9 and 20) also did not eliminate the lack of invariance, χ2 (11) = 21.59, p = .03. In short, allowing for different loadings on one or two of 18 items did not result in a non-significant chi-square for the four-factor model.

In order to examine whether estimated factor means differed in the European versus North American subsamples, we also conducted multi-group analyses using mean structures by allowing Mplus to hold the item indicator thresholds equal across groups and, by setting mean levels of each factor to 0 for the North American subsample, to estimate mean levels of the latent factors separately in the European subsample. Similar to the analyses summarized above, these analyses indicated a lack of invariance across the samples, reflecting in part the fact that the items are discriminating at different levels of the underlying factors in each set of subsamples examined (e.g., European vs. North American). As expected, these analyses also indicated higher latent mean levels of several PCL factors in the North American sample (means by default set to zero) relative to the European subsample: European subsample means = -0.36 and -0.43, for the affective and antisocial factors respectively, zs = 4.01, 4.98, ps < .001, with a similar difference approaching significance for the lifestyle factor, European subsample latent mean = -0.17, z = 1.79, p = .07. Interestingly, the European latent mean for the interpersonal factor was nonsignificantly higher than that for the North American subsample, mean = +0.13, z = 1.26, ns.

Tests of Model Invariance between Incarcerated and Detention/Probation/Clinic Samples

A similar set of analyses was conducted to assess measurement invariance as a function of setting, although, as noted above, the sample size for these comparisons was sub-optimal for assessing the four-factor model. Once again, the MGCFA for the three-factor model allowing separate estimation of parameters across the two settings demonstrated acceptable fit on both relative and absolute fit indices, χ2 (79) = 251.20, p < .001, CFI = 0.912, TLI = 0.943, RMSEA = 0.082. Once again, the analysis that required equal loadings also provided a generally reasonable fit to the data, χ2 (76) = 226.60, p < .001, CFI = 0.923, TLI = 0.949, RMSEA = 0.078, although its slightly poorer fit was confirmed by a significant chi-square difference test, χ2 (9) = 19.03, p = .02. Allowing the two subsamples to differ in the loading for one item, Item 5, was sufficient to yield a non-significant chi-square difference test, χ2 (8) = 10.21, p = .25. In summary, these analyses indicated not only configural invariance but a moderate degree of metric invariance for the three-factor model across setting.

Results were similar for the four-factor model. The unconstrained model suggested generally acceptable fit across the two settings, χ2 (129) = 469.53, p < .001, CFI = 0.874, TLI = 0.922, RMSEA = 0.090. However, it is noteworthy that this was the only unconstrained model in which an absolute or relative fit index (in this case, the CFI) fell below conventional levels of acceptability. In this case, the model requiring equal loadings (but not thresholds) yielded generally fair to acceptable fit, χ2 (121) = 449.46, p < .001, CFI = 0.878, TLI = 0.920, RMSEA = 0.092, again with the exception of the CFI. In addition, the chi-square difference test demonstrated that the fit was poorer when the loadings were required to be equal across the two settings, χ2 (13) = 53.71, p < .001. Table 3 shows that the indicator loadings for the two subsamples had appeared relatively discrepant across items on several factors when the loadings and thresholds were estimated separately in the two samples. In this case, allowing separate loadings on one or two items was not sufficient to produce invariance, suggesting that the differences in the loadings between the two subsamples are more numerous than for the other models and subsamples examined; albeit within the context that the samples were somewhat smaller than is recommended for conducting such analyses.

An additional MGCFA using mean structures was conducted to examine whether estimated factor means differed in the incarcerated versus the clinic/detention subsamples. In this analysis, mean levels of each factor were set to 0 for the incarcerated subsample. This analysis yielded estimated factor means in the clinic/detention/probation sample as follows: for the interpersonal factor, -0.86, z = 8.07; for the affective factor, -0.62, z = 6.84; for the lifestyle factor, -0.70, z = 7.48; for the antisocial factor, -0.86, z = 9.01, all ps < .001.

Discussion

The principal aim of this study was to examine the fit of the three- and four-factor models of psychopathy as assessed with the PCL: YV in a large sample of adolescent females. Because no large-scale analyses have previously been reported, this study was designed to provide greater clarity on the factor structure of the PCL: YV in adolescent females. Analyses revealed consistently acceptable fit for both models in this large sample. More specifically, the TLI and SRMR suggest good to excellent fit for both models, and the CFI and RMSEA indicate acceptable although not excellent fit for both models. Given that no prior studies had included as many participants as is recommended given the number of parameters to be estimated, these findings demonstrate that, when sample size and power are adequate, these models provide a good explanation for the pattern of intercorrelations among PCL: YV item scores.

Integrating these findings with large-scale tests of factor structure using PCL-based measures in other kinds of samples, there is now evidence that both the three- and four-factor models achieve acceptable fit in adult males, in most studies of adult females, in adolescent males, and in adolescent females (Babiak et al., 2010; Cauffman et al., 2009; Hare & Neumann, 2008; Jackson, Neumann, & Vitacco, 2007; Neumann & Hare, 2008; Neumann et al., 2006; Salekin et al., 2006; Vitacco et al., 2005). Taken together, these findings indicate that the factor structure of psychopathy as assessed by PCL measures is relatively robust. These results are important because some have argued, based on small sample studies, that the four-factor model does not fit. Moreover, it is important to keep in mind that, in contrast to studies that pit theoretical predictions against a null hypothesis, increases in statistical power in model-fitting analyses do not substantially increase the likelihood of obtaining results that corroborate a theory (e.g., see Rodgers, 2010). In other words, good fit is not a simple function of sample size. Rather, adequate sample size simply ensures a powerful test of the adequacy of a model.

As noted earlier, factor analytic studies cannot provide direct tests of the superiority of one of these factor models to the other (Brown, 2006). Moreover, the indirect evidence regarding model fit indicates that, at this level, both models provide adequate fit. Thus, the relative value of one versus the other model must be decided based on other criteria (cf., Neumann et al., 2005, 2007; Vitacco et al., 2005, 2006, 2010). Hare and Neumann (2010) and Vitacco et al. (2005) have raised questions about the methods reported by Cooke and Michie (2001) for selecting the 13 items in the three-factor model and the criteria for excluding “antisocial” items. Given that the four-factor model subsumes the three-factor model, these findings demonstrate substantial evidence that it provides a powerful conceptual architecture for understanding the correlates and mechanisms underlying psychopathy as well as for testing the predictive validity of psychopathy scores. However, research should also examine the CFA results of subsamples to determine whether there are differences across subsamples of psychopathic youth. We discuss these issues below.

The Internal Structure of PCL: YV Psychopathy in Subsamples

The subsample analyses suggest that both the three-factor and four-factor models also provide a reasonable representation of PCL: YV item score intercorrelations in most of the smaller subsamples examined. It must be emphasized that although these subsamples were larger than those in prior factor analytic studies of the PCL: YV in girls, they were smaller than is recommended for testing the four-factor model. Because the three- and four-factor models estimate 29 and 42 free parameters, tests of these models should include at least approximately 300 and 420 subjects, respectively (using a 10:1 ratio of subjects-to-free parameters; Bentler, 1995). Therefore, our subsamples of approximately 300 (Ns = 277 to 369) should have been adequate to evaluate the three-factor model but may have been somewhat underpowered with respect to the four-factor model.

That the models yielded evidence of adequate fit in the less restrictive (probation/detention/clinic) sample and in the North American sample and generally adequate fit in the European sample provides evidence for the robustness of these models. There was also some evidence for invariance of the three-factor model (i.e., allowing only one item loading to freely vary), but this same situation was not evident for the four-factor model. It is important to keep in mind that these analyses nevertheless allowed the groups to differ in their thresholds. Whereas differences in the pattern of indicator-to-factor loadings are commonly interpreted as indicating differences in factor structure, differences in thresholds refer to distinctions in the levels of the underlying latent constructs at which the items are maximally discriminating. Overall, the findings here showed that levels of psychopathy tend to be higher in prisons (i.e., settings involving long-term incarceration) than in community and detention (short-term incarceration) settings (Forth et al., 2003). Similarly, levels of psychopathic traits appear to be higher in North American than in European settings (Sullivan & Kosson, 2006; Verona, Sadeh, & Javdani, 2010). In other words, higher levels of psychopathic traits must be present, on average, in individuals from North American and prisons samples before the items provide information (discrimination) on those with (versus without) psychopathic personality features.

In spite of the generally acceptable fit for both models for subsamples in different continents and across settings, the multi-group analyses also demonstrated that the fit was better when the different subsamples were allowed to differ in some item loadings. Even allowing the indicator-to-factor loadings to differ for one or two items was sufficient to render the chi-square difference test (regarding constrained versus unconstrained models) nonsignificant for the three-factor model. Consequently, some of the item loadings are not identical across geographical region and setting. Yet, most of the differences in item-to-factor loadings that we observed are small enough that they do not result in significant differences in overall model fit. However, in each case, there was at least one PCL: YV item for which the difference in loadings was substantial enough to produce a significant chi-square difference test unless the loadings on this item were permitted to vary across groups. In summary, in most cases there were apparent differences in some loadings (as shown in Table 3), but these differences were not sufficient to produce a lack of invariance.

In contrast, for the four-factor model, even allowing the loadings on one or two items to vary across groups was not sufficient to obtain evidence of structural invariance for the four-factor model. In this case, the multi-group analysis continued to demonstrate a lack of invariance even when loadings were estimated separately for several indicators. For example, as shown in Table 3, there appear to be important differences in the loadings of PCL: YV items associated with several different psychopathy dimensions in settings involving long-term incarceration versus those involving short-term incarceration.

In spite of the sub-optimal size of the subsamples for assessing the fit of the four-factor model, the relatively weaker fit for the four-factor model in the incarcerated subsample than in the other subsamples examined (i.e., acceptable on absolute fit indices but not relative fit indices), and the lack of invariance for the four-factor model across continents and across more restrictive and less restrictive settings merit discussion. The lack of invariance in the multi-group analysis appears to reflect the fact that there were several items with different factor loadings in the long-term versus shorter-term incarceration and community samples. It is possible that both these findings reflect the relatively poor fit of the four-factor model in a single but relatively large sample (i.e., the incarcerated sample of Sevecke et al., 2009). Alternatively, it is possible that the four-factor model does not fit as well among incarcerated girls as among probation and detention and clinic girls or among samples that collapse across settings. However, this latter possibility appears to us less parsimonious given the general consistency of large sample analyses discussed above. Alternatively, the lack of invariance may reflect the possibility of fundamental differences in how well some antisocial and lifestyle items discriminate in different groups of individuals (for more information, see Mokros et al., 2010). Given that the subsamples were smaller than recommended for evaluating the fit of the four-factor model, the only way to resolve these issues would be to conduct an analysis of a large sample of incarcerated female adolescents (i.e., including 420 or more incarcerated girls).

Limitations

As discussed in the Introduction, factor analytic studies can make a valuable contribution to the construct validation enterprise (Strauss & Smith, 2009). Evidence that a structural model accounts for the pattern of covariances among item scores in a new population and thus can be generalized to the pattern observed in other populations provides powerful evidence that the larger construct which a given measure assesses is similar across the two populations. Thus, our results highlighting that scores on PCL factor indicators covaried in similar ways in adolescent girls versus what has been found with other samples suggests that the PCL-based conceptualization of psychopathy is likely similar in adolescent girls, compared with other diverse samples. At the same time, factor analytic studies have notable limitations with respect to construct validity research. Evidence for patterns of similar coherence among item scores and similar covariance among factor scores does not ensure that the underlying construct is the same. Consequently, it remains possible that the nomological network surrounding psychopathy and the four (or three) components of psychopathy is different in critical ways in adolescent females than in adolescent males.

Other types of studies and research designs are necessary to evaluate relationships between psychopathy (and psychopathy components) and the quasi-criteria linked to psychopathy in adults and in adolescent males. Even so, the existence of similar internal structure in adolescent females assessed with the PCL: YV provides a foundation that permits clearer interpretation of the pattern of correlations with theoretically informed criteria in studies of adolescent females. To the extent that item scores on the different PCL: YV items and composite scores of the factors themselves cohere in similar ways in adolescent girls and in other samples, it becomes unlikely that the construct of psychopathy is wholly different in adolescent girls than in other groups, and it becomes more likely that the similarities that are observed in the patterns of correlations between PCL psychopathy (total and composite facet) scores and scores for external criteria reflect similar mechanisms.

Conversely, in the context of similar underlying internal structure, differences in the pattern of observed correlations are likely to reflect true differential relationships between PCL-based psychopathy and other constructs (cf., Odgers et al., 2005; Kosson et al., 2011). Consequently, in light of current findings, future studies examining the convergent validity and discriminant validity of scores on the four dimensions of psychopathy in adolescent girls are especially important. In this context, studies examining construct validity that compute correlations between scores on latent variables (instead of manifest indicators) and external criteria have the advantage that they permit modeling of variance in these indicators separately from unique and error variance (Bentler, 1980).

At least one additional important limitation of our use of factor analysis is noteworthy. As noted in the Introduction, this study did not address the internal structure of other kinds of measures of psychopathy. It remains possible that studies employing self-report measures and informant (i.e., parent and teacher) measures of psychopathic traits will ultimately yield evidence of a different internal structure in adolescent females than in adolescent males and adults. As discussed by Strauss and Smith (2009), the nomothetic span of a construct refers to the extent to which different measures of a construct provide evidence for similar patterns of relations with external criteria. As we mentioned earlier (see Footnote 2), findings obtained using different kinds of psychopathy measures often do not converge with respect to the nature of the internal structure of psychopathy. Absent evidence that psychopathy is underlain by similar components across different kinds of measures (but see Williams et al., 2007, for one exception), we could not expect to see similar patterns of relationships across distinct measures. Yet attempts to understand and overcome these methodological limitations are important to overcome a monomethod bias in psychopathy research.

In general, there has been little research examining the possibility of differences in item loadings on underlying psychopathy dimensions in different samples. The evidence for differences across subsamples in the loadings of one or two items on a latent factor suggests that there may be differences in rater behavior across settings, or, more substantively, differences in the way psychopathic traits are manifested across diverse groups of individuals. Only additional research can address the replicability of these differences and the reasons why items reflecting certain features of psychopathy appear to function differently across setting and in subsamples of youth in different continents. One possibility discussed by Hare and Neumann (2006) is that items reflecting early, persistent, and versatile antisociality become increasingly important when examining non-incarcerated and community samples. However, this possibility cannot explain the current pattern of disparate loadings for items on all four dimensions in long-term incarcerated versus shorter-term detention and community samples.

Finally, one additional direction for future research is the examination of sex differences in the latent structure of psychopathy as assessed with the PCL: YV. In light of the finding that the three-factor and four-factor models yield acceptable fit in a large samples of adolescent females, it becomes possible to ask if there is invariance in the latent structure of PCL: YV psychopathy across sex. Only a multi-group analysis with large samples of males and females can address this issue.

Acknowledgments

We thank Henrik Andershed, Jacqueline Das, Heather Gretton, Derek Indoe, Malin Hemphälä, Sheilagh Hodgins, Kathleen Lewis, Roy O'Shaughnessy, R. Rowe, Corine de Ruiter, Fred Schmidt, Anders Tengström, Anita Thapar, and Todd Willoughby for providing much of the data analyzed in these studies. Several of the samples examined here are described in greater detail in the PCL: YV Manual (Forth, Kosson, & Hare, 2003). The collection of some of the data examined in this study was supported by Grant MH49111 from the National Institute of Mental Health to David S. Kosson, by funding from the William H. Donner Foundation to Craig S. Neumann, by grants from the Centers for Disease Control, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Youth Services to Randall T. Salekin, and by a grant from the Alexander Humboldt Foundation to Kathrin Sevecke.

Footnotes

Some researchers have argued that the antisocial dimension of the four-factor model should be excluded based on conceptual grounds and have specifically argued that antisociality is not central enough to psychopathy to justify its inclusion. This argument is beyond the scope of the current study, and we encourage interested readers to see Skeem and Cooke (2010) and Hare and Neumann (2008, 2010) for recent discussions of relevant issues. We note here only that some of these discussions do not make clear that the five items comprising the dimension commonly referred to as the antisocial dimension are not scored on the basis of participation in antisocial behavior per se. Rather, these items are designed to assess early, persistent, and versatile expressions of antisocial behavior that distinguish some individuals who commit antisocial behavior from other individuals who commit antisocial behavior

The internal structure of self-reports and observer ratings of psychopathic features depends upon the instruments used. For example, analyses of mother and teacher ratings of psychopathic traits in pre-adolescents, as measured by the Antisocial Process Screening Device (Frick & Hare, 2001), suggest a slightly different three-factor structure than has been identified using PCL-based measures. Factor structures resulting from analyses of self-report scores are variable across instruments, with studies reporting evidence for three-factor and four-factor structures similar to those seen in the PCL measures for scores on the Self-Report Psychopathy Scale and the Youth Psychopathy Inventory (Larsson, Andershed, & Lichtenstein, 2006; Mahmut, Menictas, Stevenson, & Homewood, 2011; Williams, Paulhus, & Hare, 2007) but reporting very different factor structures for some other self-report measures (e.g., Brinkley, Diamond, Magaletta, & Heigel, 2008). In some cases, different studies using the same instrument suggest different internal structures. For example, different factor analytic studies of scores on the Psychopathic Personality Inventory suggest disparate solutions involving two versus three dimensions (Benning, Patrick, Hicks, Blonigen, & Krueger, 2003; Neumann, Malterer, & Neumann, 2008; Uzieblo, Verschuere, Van den Bussche, & Crombez, 2010).

Forth et al. also did not use an optimal model estimation strategy for conducting their analyses. EQS Version 5.6 and LISREL Version 8.30 were not designed for use with ordinal item indicators. Mplus has advantages in analyses of ordinal indicators. When one of us re-conducted the CFAs on the 147 females examined by Forth et al. using Mplus, results indicated acceptable fit for both the three- and four-factor models.

Of course, even if a psychopathy measure functions similarly in boys and girls, it remains possible that the phenotypic similarities reflect different underlying mechanisms. Conversely, it could be argued that the same mechanisms operate in females and males, but that these mechanisms are associated with different constellations of features in girls and boys; however, this latter perspective does not appear very parsimonious.

Results for full-sample analyses including missing values indicated generally acceptable fit for the three-factor and four-factor models; however, the CFI slipped to .90 and .89 for the three- and four-factor models. Both models were also generally acceptable for the North American and European subsamples, although the CFI slipped to .89 for the four-factor model in both subsamples. For analyses limited to incarcerated girls, the CFI was low for the three-factor model (CFI = .89), and, as in principal analyses, both relative fit indices were unacceptable for the four-factor model (CFI = .82, TLI = .87). For analyses of girls on probation, under detention, or at clinics, both models yielded low CFIs (.89 and .88 for the three- and four-factor models) and borderline unacceptable RMSEAs (.099 and .097). Additional multi-group analyses demonstrated that fit was also poorer when both loadings and thresholds were constrained to be equal in the two groups. Results of these analyses are available upon request.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/pas

Contributor Information

David S. Kosson, Department of Psychology, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science

Craig S. Neumann, Department of Psychology, University of North Texas

Adelle E. Forth, Department of Psychology, Carleton University

Randall T. Salekin, Department of Psychology, University of Alabama

Robert D. Hare, Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia

Maya K. Krischer, University of Cologne

Kathrin Sevecke, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Cologne.

References

- Andershed H, Hodgins S, Tengström A. Convergent validity of the Youth Psychopathic Traits Inventory (YPI): Association with the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL: YV) Assessment. 2007;14:144–154. doi: 10.1177/1073191106298286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiak P, Neumann CS, Hare RD. Corporate psychopathy: Talking the walk. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2010;28:174–193. doi: 10.1002/bsl.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DLA, Whitman L, Kosson DS. Reliability and construct validity of Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version scores in incarcerated adolescent girls. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2011;38:965–987. [Google Scholar]

- Benning SD, Patrick CJ, Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Krueger R. Factor structure of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory: Validity and implications for clinical assessment. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15:340–350. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Multivariate analysis with latent variables: Causal modeling. Annual Review of Psychology. 1980;31:419–456. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley CA, Diamond PM, Magaletta PR, Heigel CP. Cross-validation of Levenson's Psychopathy Scale in a sample of federal female inmates. Assessment. 2008;15:464–482. doi: 10.1177/1073191108319043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Kimonis ER, Dmitrieva J, Monahan KC. A multimethod assessment of juvenile psychopathy: Comparing the predictive utility of the PCL: YV, YPI, and NEO PRI. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:528–542. doi: 10.1037/a0017367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DJ, Michie C. Refining the construct of psychopath: Towards a hierarchical model. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13(2):171–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DJ, Michie C, Hart SD, Clark DA. Reconstructing psychopathy: Clarifying the significance of antisocial and socially deviant behavior in the diagnosis of psychopathic personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:337–357. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.4.337.40347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, de Ruiter C, Doreleijers T, Hillege S. Reliability and construct validity of the Dutch Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version: Findings from a sample of male adolescents in a juvenile justice treatment institution. Assessment. 2009;16:88–102. doi: 10.1177/1073191108321999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flight JI, Forth AE. Instrumentally violent youths: The roles of psychopathic traits, empathy and attachment. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2007;34:739–751. [Google Scholar]

- Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:466–491. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forth AE, Kosson D, Hare R. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version. New York: Multi-Health Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Hare RD. The Antisocial Process Screening Device. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gretton and Hare. Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version scores. 2002 Unpublished raw data. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. Manual for the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. 2nd. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Neumann CS. The PCL-R assessment of psychopathy: Development, structural properties, and new directions. In: Patrick C, editor. Handbook of Psychopathy. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 58–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Neumann CS. Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:217–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Neumann CS. Psychopathy and its measurement. In: Corr PJ, Matthews G, editors. Cambridge Handbook of Personality Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 660–686. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Neumann CS. The role of antisociality in the psychopathy construct: Comment on Skeem and Cooke (2010) Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:446–454. doi: 10.1037/a0013635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart SD, Cox DN, Hare RD. Manual for the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV) Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Evaluating model fit. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Issues, concepts, and applications. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Indoe D. Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version scores. 2002 Unpublished raw data. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RL, Neumann CS, Vitacco ML. Impulsivity, anger, and psychopathy: The moderating effect of ethnicity. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:289–304. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Cauffman E, Miller JD, Mulvey E. Investigating different factor structures of the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth version: Confirmatory factor analytic findings. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:33–48. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennealy PJ, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ. Validity of factors of the Psychopathy Checklist--Revised in female prisoners: Discriminant relations with antisocial behavior, substance abuse, and personality. Assessment. 2007;14:323–340. doi: 10.1177/1073191107305882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kosson DS, Cyterski TD, Steuerwald BL, Neumann C, Walker-Matthews S. The reliability and validity of the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version in non-incarcerated adolescent males. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:97–109. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krischer MK, Sevecke K. Early traumatization and psychopathy in female and male juvenile offenders. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2008;31:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubak FA, Salekin RT. Psychopathy and anxiety in children and adolescents: New insights on developmental pathways to offending. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009;31:271–284. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H, Andershed H, Lichtenstein P. A genetic factor explains most of the variation in the psychopathic personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:221–230. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmut MK, Menictas C, Stevenson RJ, Homewood J. Validating the factor structure of the Self-Report Psychopathy Scale in a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 2011 Apr 25; doi: 10.1037/a0023090. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Balla JR, McDonald RP. Goodness-of-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: The effect of sample size. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:391–410. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau KT, Wen Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indices and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler's (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:320–341. [Google Scholar]

- Mokros A, Neumann CS, Stadtland C, Osterheider M, Nedopil N, Hare RD. Assessing Measurement Invariance of PCL-R Assessments from File Reviews for North-American and German Offenders. International Journal of Psychiatry & Law. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrie DC, Cornell DG, Kaplan S, McConville D, Levy-Elkon A. Psychopathy scores and violence among juvenile offenders: A multi-measure study. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2004;22:49–67. doi: 10.1002/bsl.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Hare RD. Psychopathic traits in a large community sample: Links to violence, alcohol use, and intelligence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:893–899. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Hare RD, Newman JP. The super-ordinate nature of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:102–117. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.2.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Kosson DS, Forth AE, Hare RD. Factor structure of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL: YV) in incarcerated adolescents. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:142–154. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Kosson DS, Salekin RT. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Psychopathy Construct: Methodological and Conceptual Issues. In: Hervé H, Yuille JC, editors. The Psychopath: Theory, Research, and Practice. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Malterer MB, Newman JP. Factor structure of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI): Findings from a large incarcerated sample. Psychological Assessment. 2008;20:169–174. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Vitacco MJ, Hare RD, Wupperman P. Reconstruing the “reconstruction” of psychopathy: A comment on Cooke, Michie, Hart, and Clark. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:624–640. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.6.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Reppucci ND, Moretti MM. Nipping psychopathy in the bud: An examination of the convergent, predictive, and theoretical utility of the PCL: YV among adolescent girls. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2005;23:743–763. doi: 10.1002/bsl.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K, O'Shaughnessy R. Predictors of violent recidivism in juvenile offenders; 1998, June; Poster presented at the annual convention of the Candadian Psychological Association; Edmonton, Alberta. [Google Scholar]

- Penney SR, Moretti MM. The relation of psychopathy to concurrent aggression and antisocial behavior in high-risk adolescent girls and boys. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2007;25:21–41. doi: 10.1002/bsl.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JL. The epistemology of mathematical and statistical modeling: A quiet methodological revolution. American Psychologist. 2010;65:1–12. doi: 10.1037/a0018326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Carleton University; Ottawa, Ontario: 2002. Predictors of criminal offending: Evaluating measures of risk/needs, psychopathy, and disruptive behavior disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT. Psychopathy and recidivism from mid-adolescence to young adulthood: Cumulating legal problems and limiting life opportunities. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:386–395. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT, Brannen DN, Zalot AA, Leistico AR, Neumann CS. Factor structure of psychopathy in youth: Testing the applicability of the new four factor model. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2006;33:135–157. [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT, Neumann CS, Leistico AR, DiCicco TM, Duros RL. Psychopathy and comorbidity in a young offender sample: Taking a closer look at psychopathy's potential importance over the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:416–427. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT, Leistico AR, Trobst KK, Schrum CL, Lochman JE. Adolescent psychopathy and personality theory-the interpersonal circumplex: Expanding evidence of a nomological net. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:445–460. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-5726-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT, Neumann CS, Leistico AR, Zalot AA. Psychopathy in youth and intelligence: An investigation of Cleckley's hypothesis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:731–742. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT, Rogers R, Sewell KW. Construct validity of psychopathy in a female offender sample: A multitrait–multimethod evaluation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:576–585. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt F, McKinnon L, Chattha HK, Brownlee K. Concurrent and predictive validity of the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version across gender and ethnicity. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:393–401. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.4.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrum CL, Salekin RT. Psychopathy in adolescent female offenders: An item response theory analysis of the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2006;24:39–63. doi: 10.1002/bsl.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevecke K, Lehmkuhl G, Krischer MK. Examining relations between psychopathology and psychopathy dimensions among adolescent female and male offenders. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;18:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-0707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevecke K, Pukrop R, Kosson DS, Krischer MK. Factor structure of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version in German female and male detainees and community adolescents. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:45–56. doi: 10.1037/a0015032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Cauffman E. Views of the Downward Extension: Comparing the Youth Version of the Psychopathy Checklist with the Youth Psychopathic Traits Inventory. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2003;21:737–770. doi: 10.1002/bsl.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale KC, Olver ME, Wong SCP. The Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version and adolescent and adult recidivism: Considerations with respect to gender, ethnicity, and age. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:768–781. doi: 10.1037/a0020044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss ME, Smith GT. Construct validity: advances in theory and methodology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton SK, Vitale JE, Newman JP. Emotion among women with psychopathy during picture perception. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:610–619. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EA, Kosson DS. Ethnic and cultural variations in psychopathy. In: Patrick CJ, editor. Handbook of psychopathy. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 437–458. [Google Scholar]

- Uzieblo K, Verschuere B, Van den Bussche E, Crombez G. The validity of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised in a community sample. Assessment. 2010;17:334–346. doi: 10.1177/1073191109356544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona E, Sadeh N, Javdani S. The influences of gender and culture on child and adolescent psychopathy. In: Salekin RT, Lynam DR, editors. Handbook of child and adolescent psychopathy. New York: Guilford; 2010. pp. 317–342. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent GM, Odgers CL, McCormick AV, Corrado RR. The PCL: YV and recidivism in male and female juveniles: A follow-up into young adulthood. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2008;31:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitacco MJ, Neumann CS, Caldwell MF. Predicting antisocial behavior in high-risk male adolescents: Contributions of psychopathy and instrumental violence. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2010;37:833–846. [Google Scholar]

- Vitacco MJ, Neumann CS, Caldwell MF, Leistico A, Van Rybroek GJ. Testing factor models of the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version and their association with instrumental aggression. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2006;87:74–83. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8701_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]