Significance

Humans help strangers even if the strangers will not directly help them in the future. The so-called indirect reciprocity seems to support large-scale cooperation in human society. We revealed functional and anatomical neural bases of two types of indirect reciprocity by combining group and neuroimaging experiments. Reputation-based indirect reciprocity activated the precuneus, a brain region associated with self-centered cognition. Indirect reciprocity occurring as a succession of pay-it-forward behaviors specifically recruited the anterior insula, a region related to affective empathy. Furthermore, task-irrelevant neural fingerprints of these brain regions are predictive of the individual’s tendency of cooperation. These results in particular explain why we often conduct seemingly irrational cooperation such as pay-it-forward reciprocity.

Keywords: altruism, fMRI, VBM

Abstract

Cooperation is a hallmark of human society. Humans often cooperate with strangers even if they will not meet each other again. This so-called indirect reciprocity enables large-scale cooperation among nonkin and can occur based on a reputation mechanism or as a succession of pay-it-forward behavior. Here, we provide the functional and anatomical neural evidence for two distinct mechanisms governing the two types of indirect reciprocity. Cooperation occurring as reputation-based reciprocity specifically recruited the precuneus, a region associated with self-centered cognition. During such cooperative behavior, the precuneus was functionally connected with the caudate, a region linking rewards to behavior. Furthermore, the precuneus of a cooperative subject had a strong resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) with the caudate and a large gray matter volume. In contrast, pay-it-forward reciprocity recruited the anterior insula (AI), a brain region associated with affective empathy. The AI was functionally connected with the caudate during cooperation occurring as pay-it-forward reciprocity, and its gray matter volume and rsFC with the caudate predicted the tendency of such cooperation. The revealed difference is consistent with the existing results of evolutionary game theory: although reputation-based indirect reciprocity robustly evolves as a self-interested behavior in theory, pay-it-forward indirect reciprocity does not on its own. The present study provides neural mechanisms underlying indirect reciprocity and suggests that pay-it-forward reciprocity may not occur as myopic profit maximization but elicit emotional rewards.

Humans often help strangers even if helping is a costly behavior and repeated encounters among the same peers are not expected in the future. When cooperation among unacquainted individuals is established, the cost of the cooperation that an individual owes is reimbursed by somebody else’s cooperation toward the individual. This so-called indirect reciprocity has been reported in a wide range of behavioral experiments and human communities, and it is thought to be a prime candidate mechanism for explaining large-scale cooperation among nonkin (1–3). Empirically, humans exhibit two types of indirect reciprocity: reputation-based reciprocity, in which they help others with good reputations to gain good reputations themselves (4–8); and pay-it-forward reciprocity, in which, independently of reputations, they help others after being helped by someone else (9–13).

Evolutionary game theory explains reputation-based reciprocity as self-interested stable behavior under social learning (14–18). In contrast, cooperation in pay-it-forward reciprocity is theoretically unstable unless it is combined with an independent mechanism that allows evolution of cooperation (14, 19–22), because helping others is not apparently rational in the absence of a reputation system or a different mechanism that independently enhances cooperation (3). Therefore, mechanisms by which humans commonly show pay-it-forward reciprocity remain unclear.

The lack of theoretical underpinning of pay-it-forward reciprocity leads us to postulate that pay-it-forward reciprocity may involve neural mechanisms associated with emotional factors such as compassion and affective empathy and may be interpreted as behavior driven by positive emotions such as gratitude (11, 20). In contrast to direct reciprocity, in which two individuals mutually cooperate in repeated interactions (23–26), neural evidence for indirect reciprocity is absent. It is presumably because neural measurement of indirect reciprocity requires a relatively large number of human participants simultaneously playing the game and their brain activity has to be recorded during the game. Here, we overcame the technical difficulty in imaging indirect reciprocity by combining a purely behavioral group experiment and a subsequent neuroimaging experiment whose stimuli were determined by the results of the behavioral experiment (Fig. 1 A and B). In the neuroimaging experiment, we examined brain activity that was recorded by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while subjects connected as a chain sequentially made decisions in two apparently similar economic games (i.e., pay-it-forward and reputation-based reciprocity games). To identify neural fingerprints encoding subjects’ behavioral tendency in the games, resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) and regional gray matter volumes were also measured. With this experimental design, we provided functional and anatomical neural bases of indirect reciprocity. We particularly sought for neural underpinning of positive reciprocity, i.e., cooperation after observing others’ cooperation. We found evidence supporting the hypothesis that, compared with reputation-based reciprocity, pay-it-forward reciprocity is supported by a neural mechanism associated with compassion rather than maximization of self-profits.

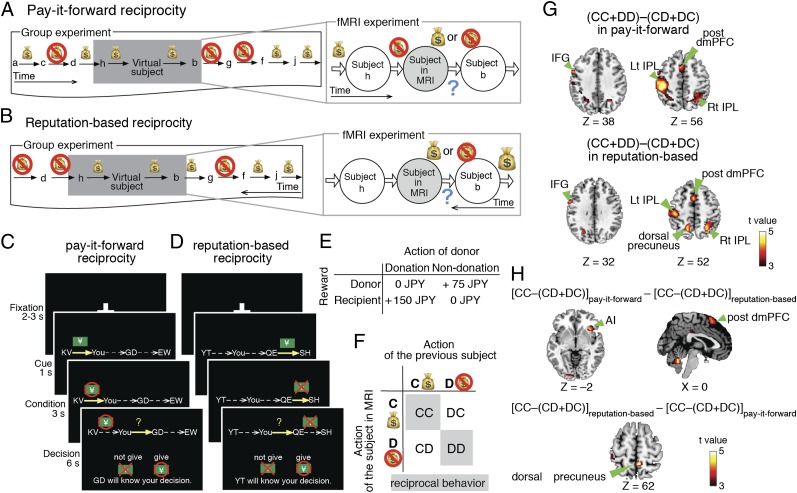

Fig. 1.

Experimental design and behavioral results. (A and B) Overall experimental design. Various chains of donation or nondonation were collected in group experiments with four groups of 10 subjects. We conducted the fMRI experiments by embedding the scanned subjects into the chains of the behavioral patterns collected in the group experiments. In the pay-it-forward reciprocity (also known as upstream reciprocity, generalized reciprocity, and generalized exchange) game (A), a subject undergoing fMRI made decisions (i.e., to donate or not to donate) after knowing whether the subject had received a donation from another subject. In the reputation-based reciprocity (also known as downstream reciprocity) game (B), a subject undergoing fMRI made decisions after knowing whether the prospective recipient had donated to a different peer. In both games, the decision of each subject in the group experiments was also conditioned on that of the previous subject, who was either a different subject in the group experiments or the virtual subject in the fMRI experiments. The displayed names of the subjects were randomly selected such that the subjects could not identify the other subjects. (C and D) Stimuli presented in fMRI. Circles and crosses indicate donation (cooperation) and nondonation (defection), respectively. Note that the subject knows the decision of only the neighboring peer who makes a decision immediately before himself/herself. (E) Payoff matrix showing the amount of reward in a single game. (F) Cooperation after CC and defection after DD are defined as reciprocal behaviors. (G) Brain activations specific to reciprocal behavior. IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; Lt/Rt IPL, left/right inferior parietal lobule; post dmPFC, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. Left and Right show the activations in pay-it-forward and reputation-based reciprocity, respectively. All activations in G and H survive P < 0.05 corrected by family-wise error (FWE). (H) Difference in brain activity defined as CC–(CD+DC) between two types of reciprocity. AI, anterior insula.

Results

To simulate in fMRI experiments the indirect reciprocity games that involve a series of anonymous one-shot interactions among unacquainted individuals, we first conducted behavioral group experiments with 40 subjects. We recorded the sequences of behavioral patterns consisting of donation (i.e., cooperation) and nondonation (i.e., defection; Fig. 1 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). On the basis of the behavioral data, we prepared stimuli for the subsequent fMRI experiments in which 48 new subjects separately played two types of indirect reciprocity game: the pay-it-forward and reputation-based reciprocity games (Fig. 1 C and D). Before the fMRI experiments, each subject was informed that, although there was no other subject simultaneously playing the game, the subject was embedded in a group experiment in exactly the same manner as were the other subjects and that the subject’s actions would affect other players’ actions and rewards (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Materials for instructions).

Comparison Between Group and fMRI Experiments.

This experimental design allowed us to observe indirect reciprocity in fMRI. The distribution of donation strategies obtained from the 48 scanned subjects was similar to that obtained from the 40 subjects in the group experiment (P > 0.7, Friedman test; SI Appendix, Table S1). Postscanning questionnaires also revealed that the subjects had understood that their decisions would influence unacquainted others’ decisions and rewards (t47 = 3.0, P = 0.005, one-sample t test; SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Therefore, the scanned subjects were likely to feel as if they were embedded in the chain of donation games together with other subjects in the group experiment.

Among the 48 healthy subjects who were scanned, 21 subjects tended to behave reciprocally in both the pay-it-forward and reputation-based reciprocity games (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Table S1; see also SI Appendix, Supplementary Experimental Procedures for evaluation of reciprocity of each subject). We regarded cooperation after observing cooperation (CC) and defection after observing defection (DD) as reciprocal behaviors (Fig. 1F) (27). In the following analysis, we mainly investigated the activity and anatomy of the brain in the 21 reciprocal subjects, who showed indirect reciprocity with sufficient frequency. As shown later, we also analyzed the data obtained from subjects that did not frequently show reciprocal behavior.

Behavioral Results.

Behaviorally, neither a repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the fraction of the responses [type of action (CC and DD) × type of game (pay-it-forward and reputation-based)] nor an ANOVA of the response time revealed any significant effects (P > 0.5; SI Appendix, Fig. S5). This observation assures us that there was behavioral comparability between the two types of indirect reciprocity. Next, the fractions of CC and DD did not significantly change during the course of the fMRI experiment (P > 0.4, Friedman test; SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Therefore, we can exclude the effect of learning on the activity of reward-related brain regions—an effect that has been reported for direct reciprocity (23–26).

Brain Regions Associated with Indirect Reciprocity.

We then searched for differences in brain regions associated with the two types of indirect reciprocity. To this end, we first estimated brain activity related to reciprocal behaviors (i.e., CC and DD) in each type of indirect reciprocity. The baseline was defined by the fMRI signals during nonreciprocal behaviors (CD, i.e., defection after observing cooperation; and DC, i.e., cooperation after observing defection). We compared the reciprocity-specific activity [i.e., (CC+DD)–(CD+DC)] between the two types of reciprocity but could not detect a significant difference even with a moderate statistical threshold (P = 0.005, uncorrected). Consistent with this result, the two types of indirect reciprocity recruited approximately the same brain regions including left frontal gyrus, posterior dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (post dmPFC), and bilateral inferior parietal lobules (PFWE < 0.05; Fig. 1G and SI Appendix, Table S2).

Brain Regions Associated with Reciprocal Cooperation.

We then hypothesized that positive reciprocity (CC) and negative reciprocity (DD) were supported by different brain mechanisms in different types of indirect reciprocity. Averaging the positive and negative reciprocity by measuring the contrast (CC+DD)–(CD+DC) (Fig. 1G and SI Appendix, Table S2) may have masked the difference. Here, we separately analyzed fMRI signals during CC and those during DD. To secure a sufficient amount of data for nonreciprocal behavior, we measured CC–(CD+DC) instead of CC–CD or CC–DC to examine neural correlates of positive reciprocity. We found that CC in pay-it-forward reciprocity activated the right anterior insula (AI) and post dmPFC more than CC in reputation-based reciprocity did (PFWE < 0.05; Fig. 1H, Left). CC in reputation-based reciprocity specifically recruited the dorsal precuneus (PFWE < 0.05; Fig. 1H, Right). However, there was no significant difference in brain activity during DD [i.e., DD–(CD+DC)] between the two types of indirect reciprocity (P > 0.005, uncorrected). These results suggest that pay-it-forward reciprocity and reputation-based reciprocity are different in neural mechanisms underlying positive reciprocity.

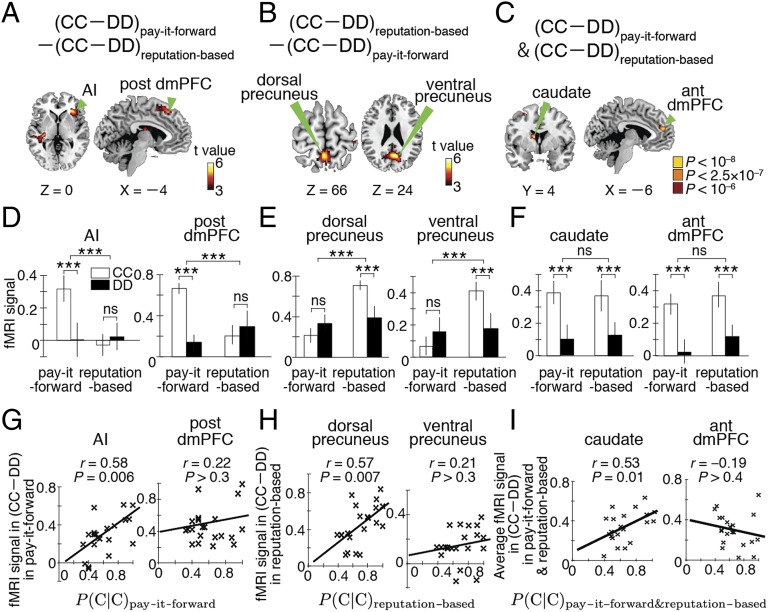

We next looked at CC-specific brain activity defined as the difference in fMRI signals between CC and DD (i.e., CC–DD). In fact, an ANOVA of fMRI signals [type of action (CC and DD) × type of game (pay-it-forward and reputation-based)] detected a significant interaction between the type of action and the type of game (F1,80 > 21.1, PFWE < 0.05; SI Appendix, Table S3). CC-specific activity in the right AI and post dmPFC was significantly larger during pay-it-forward than reputation-based reciprocity (t20 > 4.6, PFWE < 0.05; Fig. 2A). CC-specific activity in the dorsal and ventral precuneus showed the opposite pattern (t20 > 4.9, PFWE < 0.05; Fig. 2B). By conducting a region-of-interest (ROI) analysis (Fig. 2 D and E) and whole-brain analysis within each type of reciprocity (SI Appendix, Table S4), we confirmed that none of these activations represented the difference in DD-specific activity (DD–CC; SI Appendix, Supplementary Results). A conjunction analysis revealed that CC-specific activity in the right caudate and anterior dmPFC was concomitantly large in both types of indirect reciprocity (P < 10−8; Fig. 2C; SI Appendix, Table S3); this result was also confirmed by ROI analysis (Fig. 2F). These results were stably observed even when we excluded the subjects with random strategy (SI Appendix, Table S5) and when we used the tendency of reciprocal behavior as an additional covariate (SI Appendix, Table S6).

Fig. 2.

Brain activations related to positive indirect reciprocity. (A–C) CC-specific brain activations. ant, anterior. A and B are activation maps with P < 0.05 corrected by FWE. C shows the result of a conjunction analysis of the two types of indirect reciprocity: red, orange, and yellow areas indicate binary-valued maps derived from multiplication of the two maps shown in A and B with P < 10−3, P < 5 × 10−4, and P < 10−4, respectively. (D–F) Activity of six brain regions in the two types of reciprocal behavior and two types of indirect reciprocity game. Error bars: SEM. ***P < 0.001 in a paired t test. ns, no significant difference. (G–I) Across-subject comparison between the activity of different brain regions and the probability of cooperation after observing cooperation [i.e., P(C|C)]. r represents Pearson’s correlation coefficient between brain activity and P(C|C).

Next, to clarify ROIs that were the most responsible for the corresponding positive reciprocity, we compared the activity of these six ROIs with the probability of cooperation across subjects. Among the four ROIs specific to either type of indirect reciprocity (Fig. 2 A and B), only the activity of the AI and dorsal precuneus was positively correlated with the probability of CC in pay-it-forward and reputation-based reciprocity, respectively (Pearson’s correlation r19 > 0.57, PBonferroni < 0.05; Fig. 2 G and H). Among the two ROIs activated by cooperation under both types of indirect reciprocity (Fig. 2 C and F), only the activity of the caudate was positively correlated with the overall probability of CC (r19 > 0.53; PBonferroni < 0.05; Fig. 2I).

These results show that positive pay-it-forward reciprocity mainly recruits the AI, a region known to be related to affective empathy (28–34) and unreciprocated cooperation (35). In contrast, positive reputation-based reciprocity recruits the dorsal precuneus, a region associated with self-centered cognition (36) and logical inference of others’ intention (37, 38). The caudate, a region linking reward to behavior (39, 40), is involved in cooperation in both types of indirect reciprocity.

Task-Specific Functional Connectivity.

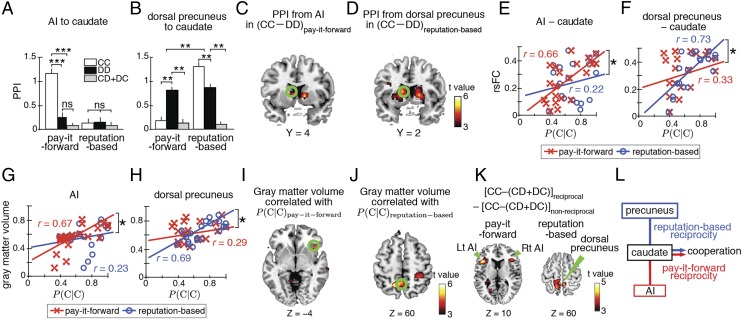

We then examined task-specific functional connectivity by using psycho–physiological interactions (PPIs). The PPI from the AI to the caudate exclusively increased during CC in pay-it-forward reciprocity (t20 > 3.7, PBonferroni < 0.05, paired t test; Fig. 3A). The PPI from the dorsal precuneus to the caudate exclusively increased during CC in reputation-based reciprocity (t20 > 2.9, PBonferroni < 0.05; Fig. 3B). We confirmed the spatial specificity of these results by exploratory whole-brain PPI analyses (PFWE < 0.05; Fig. 3 C and D and SI Appendix, Table S7). Therefore, cooperative behavior in pay-it-forward reciprocity, but not reputation-based reciprocity, selectively recruits an empathy- and compassion-based neural system centered around the AI.

Fig. 3.

Task-specific functional connectivity. (A and B) We compared task-specific functional connectivity by calculating the PPIs. Error bars: SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 in a paired t test. ns, no significant difference. (C and D) Results of explanatory PPI analysis at the whole-brain level with the AI and dorsal precuneus as a seed, respectively. Blue circles indicate the location of the caudate as determined from the results shown in Fig. 2C. (E and F) Comparison between rsFC and probability of cooperation after observing cooperation (i.e., CC) across subjects. The rsFC between the AI and caudate and that between the dorsal precuneus and caudate are presented in E and F, respectively. In E–H, the red and blue lines indicate linear regressions in the case of pay-it-forward and reputation-based reciprocity, respectively. *P < 0.05. (G and H) Regional gray matter volume of the AI (G) and dorsal precuneus (H) compared with the probability of CC across subjects. (I and J) Results of exploratory VBM analysis at the whole-brain level. Circles in I and J indicate the locations of the AI and dorsal precuneus as determined in Fig. 2 A and B, respectively. (K) Images show the difference in the CC–(CD+DC) activity between the reciprocal and nonreciprocal subjects. (L) Schematic of neural mechanisms for indirect reciprocity implied by the present findings.

Resting-State Functional Connectivity.

These results imply that individuals’ behavioral tendency in the indirect reciprocity games may be encoded in some intrinsic neural circuits centered around the AI and dorsal precuneus. To further examine this question, we first calculated the task-irrelevant rsFC among the AI, dorsal precuneus, and caudate. The rsFC between the AI and caudate was positively correlated with the probability of CC in pay-it-forward reciprocity across subjects (r19 = 0.66, P < 0.005; Fig. 3E), but not with that in reputation-based reciprocity (r19 = 0.22, P > 0.34; Fig. 3E). The rsFC between the dorsal precuneus and caudate was positively correlated with the probability of CC in reputation-based reciprocity (r19 = 0.73, P < 0.001; Fig. 3F), but not in pay-it-forward reciprocity (r19 = 0.33, P > 0.13; Fig. 3F). In each rsFC, the r values for the two types of indirect reciprocity were significantly different (z > 1.7, P < 0.05; Fig. 3 E and F).

Regional Gray Matter Volume.

We then estimated anatomically defined gray matter volumes by conducting voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis. The regional gray matter volume of the AI and dorsal precuneus was strongly correlated with the probability of CC in pay-it-forward and reputation-based reciprocity, respectively (r19 > 0.67, P < 0.002; Fig. 3 G and H). The significant correlation was specific to the corresponding type of reciprocity (z > 1.6, P < 0.05). Exploratory whole-brain VBM analysis also confirmed the spatial specificity of these results (PFWE < 0.05; Fig. 3 I and J and SI Appendix, Table S8). These task-irrelevant results regarding the rsFC and regional gray matter further support the notion that positive pay-it-forward reciprocity depends on the AI-centered neural mechanism.

Comparison Between Reciprocal and Nonreciprocal Subjects.

Finally, we compared brain activity between the 21 reciprocal subjects analyzed so far and 12 nonreciprocal subjects. The nonreciprocal subjects were defined as those showing at least five CC and DD responses in both types of indirect reciprocity games, with the reciprocal subjects excluded. The threshold of the five responses was necessary for conducting reliable statistical analysis.

During CC in the pay-it-forward reciprocity game, the bilateral AIs were activated more strongly in the reciprocal than nonreciprocal subjects (PFWE < 0.05; Fig. 3K, Left). During CC in the reputation-based reciprocity game, the dorsal precuneus was activated more strongly in the reciprocal than nonreciprocal subjects (PFWE < 0.05; Fig. 3 K, Right). These activations in the right AI and precuneus were located near those shown in Fig. 2 A and B. In addition, for the nonreciprocal subjects, neither CC–DD activity in the right AI in pay-it-forward reciprocity nor that in the precuneus in reputation-based reciprocity was significant (P > 0.005, uncorrected; SI Appendix, Supplementary Results and Fig. S6). These results support the notion that the right AI and precuneus are the core brain regions for positive reciprocity in pay-it-forward and reputation-based reciprocity, respectively. Furthermore, during DD, the reciprocal subjects more strongly recruited the precuneus than the nonreciprocal subjects, but not the AI in both types of indirect reciprocity (P > 0.005, uncorrected; SI Appendix, Fig. S7). This result also supports the important role of the AI in positive pay-it-forward reciprocity but not in negative pay-it-forward or positive and negative reputation-based reciprocity.

Discussion

The present findings provide functional and anatomical neural correlates of cooperative behavior in two types of indirect reciprocity. Cooperative behavior in the reputation-based indirect reciprocity recruited the brain region for self-centered cognition (i.e., the precuneus) and increased the task-related functional connectivity (i.e., PPI) between the precuneus and a region associated with general reward systems (i.e., the caudate). The gray matter volume of the precuneus and task-irrelevant functional connectivity (i.e., rsFC) between the precuneus and caudate were highly predictive of the subject’s tendency to cooperate in the reputation-based reciprocity game. In contrast, cooperative behavior in the pay-it-forward reciprocity game activated the empathy-associated brain region (i.e., AI) and enhanced PPI between the AI and the caudate. Furthermore, the subject’s tendency of cooperation in the pay-it-forward reciprocity game was positively correlated with the regional gray matter volume of the AI and rsFC between the AI and caudate. Although we need to be cautious about inferring recruited cognitive components on the basis of the activation of specific brain regions, these results imply that positive emotions such as gratitude and affective empathy represented in the AI are evaluated as reward in the caudate such that subjects show positive reciprocity in the pay-it-forward reciprocity game (Fig. 3L). Emotional rewards may be a key factor in reconciling the abundance of pay-it-forward reciprocity in human society and its theoretical instability. Future theoretical models of pay-it-forward reciprocity may benefit from incorporating emotional factors.

Although the region is known to be activated during other cognitive tasks including cognitive control (41) and awareness (42), the AI is one of the main brain regions constituting a core network of empathy (28–33). In particular, the AI is thought to be associated with the affective type of empathy in which others’ experiences are perceived as if they were one’s own experiences. In fMRI experiments, the AI is activated when subjects feel affection and sympathy toward others in contrast to when they are conducting logical inference of others’ intention; the latter corresponds to mentalizing or cognitive empathy (30, 31, 34). The association between the AI and affective empathy is also reported in terms of the regional gray matter volume of healthy subjects (32) and patients with psychiatric disorders (28). These results are consistent with our view that positive reciprocity in pay-it-forward reciprocity may use affective empathy that is represented in the AI.

In contrast, the precuneus is activated when a subject evaluates risk and benefits or infers others’ intentions without sympathizing with them (31, 34, 36–38). Logical inference presumably used in such a situation could be beneficial for maximizing material rewards such as money and reputations. This idea is consistent with the strong association between the precuneus and cooperative behavior in the reputation-based reciprocity game revealed in the present study. In reputation-based reciprocity, the precuneus may be used for calculating the benefit of establishing good reputations minus the cost of helping.

We found that the caudate was functionally connected with both the AI and precuneus. A line of fMRI studies reporting activation of the caudate suggests two major functions of the caudate (39, 40): learning rewards and linking rewards to actual behavior (35). Because we did not detect the effect of learning (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), the activation of the caudate observed in our experiments may be ascribed to the linkage between rewards and subsequent behavior. The caudate might relay the information on emotional or material rewards represented in the AI and precuneus, respectively, to actual behavior (Fig. 3L). The connection from the AI to the caudate may hamper the payoff-maximizing action (i.e., noncooperation after receiving cooperation from someone) by suppressing the precuneus-caudate pathway and allow the decision system to regard positive pay-it-forward reciprocity as rewarding behavior. The present interpretations on the functions of the AI, precuneus, and caudate seem to be persuasive, although these brain regions may be also involved in other cognitive processes.

A different interpretation of the present findings is social conformity (43, 44). The posterior mPFC and insula are known to be recruited when individuals obey opinions of others in the same group (45–47). In the present study, we attempted to minimize the effect of conformity by contrasting CC and DD; both CC and DD are consistent with social conformity. However, CC may recruit conformity-related neural mechanisms more than DD does. If so, the observed activations in the AI could be relevant to social conformity.

A yet different possible interpretation of our results on positive reciprocity in the pay-it-forward game is the so-called social image (48). A behavioral study using the dictator game suggested that typically developed individuals cooperate because they like to be perceived as fair to maintain their private “social image,” although other parties judging the fairness or reputation of the subjects were absent (49), as in our pay-it-forward game. We cannot rule out the possibility that such a social image operated in our experiments. However, social images investigated with optional donation to a charity are known to mainly activate reward-related brain regions, such as the ventral striatum (50), rather than those identified in the present study. Therefore, the social image may have played a relatively minor role in our experiments.

In evolutionary game theory, cooperation via pay-it-forward reciprocity is difficult to explain as a payoff-maximizing behavior (3). It evolves only when theoretical models are complemented by an independent cooperation-enhancing mechanism, such as small population size (14), mobility of players (19), repeated interaction between the same partners (20), spatial or network structure (21, 22), or assortative interaction (21). However, direct reciprocity (51) and reputation-based indirect reciprocity (14–18) evolve much more easily. In principle, evolutionary game theory is silent about the proximate mechanisms used for producing evolutionarily stable behavior. It is an intriguing coincidence that both direct reciprocity and reputation-based indirect reciprocity are governed by the reward system, whereas pay-it-forward indirect reciprocity needs the involvement of empathy-related neural circuitry. A possible evolutionary interpretation is that empathy facilitating acquisition of group-beneficial traits has evolved in the course of gene-culture coevolutionary processes and pay-it-forward reciprocity is ontogenetically acquired on the basis of such a neural mechanism (52). Our neuroscientific evidence may shed light on the ongoing controversy on the origin of human cooperation.

Materials and Methods

Overall Design.

The study consisted of two experiments: a group experiment and an fMRI experiment (Fig. 1 A and B). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects in both of the group (n = 40) and the MRI experiments (n = 50). All experiments complied with the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki. In the MRI experiment, behavioral responses of two subjects were not recorded owing to a technical problem. Therefore, we analyzed behavioral data obtained from the remaining 48 subjects. See SI Appendix for the details about the group and MRI experiments using a 3T magnetic resonance imaging scanner (Discovery MR750w; GE). High-resolution T1-weighted images [repetition time (TR) = 6.8 ms; 1 × 1 × 1 mm] and T2*-weighted functional images (TR = 3 s; echo time = 35 ms; 4 × 4 × 4 mm; 42 slices) were acquired.

Behavioral Analysis.

On the basis of behavior of each subject, we classified the subjects into the reciprocal and nonreciprocal individuals (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods for details). In the group experiment, there were 8 and 12 reciprocating subjects among 40 subjects in the pay-it-forward and reputation-based reciprocity games, respectively. In the fMRI experiment, there were 22 and 37 reciprocating subjects among 48 subjects in the pay-it-forward and reputation-based reciprocity games, respectively. All of the reciprocating subjects in the pay-it-forward reciprocity game were also reciprocating subjects in the reputation-based reciprocity game in the fMRI experiment. Because the MRI data recorded from one of the 22 reciprocating subjects in the pay-it-forward reciprocity game were lost owing to technical problems in transferring the data, we submitted the data recorded from the remaining 21 reciprocating subjects identified in the pay-it-forward reciprocity game to the main part of the imaging analysis. Among the remaining nonreciprocal subjects, the data obtained from 12 subjects who showed at least five CC responses in both types of games were used. We analyzed the number of reciprocal behaviors and reaction time by using a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA [type of action (CC and DD) × type of game (pay-it-forward and reputation-based)].

Imaging Analysis.

We first analyzed fMRI images by using a general linear model in a standard event-related design in a single-subject level. At a group level, we used the random effects model to analyze the fMRI images that were subjected to analysis at the single-subject level (PFWE < 0.05). The post hoc t tests adopted P < 0.05 that was Bonferroni corrected. In a conjunction analysis using a conservative null hypothesis, we adopted three different statistical thresholds (i.e., 10−6, 2.5 × 10−7, and 10−8, uncorrected). Using task-irrelevant resting-state fMRI signals, we examined resting-state functional connectivity. Using high-resolution anatomical images, we performed VBM analysis. See SI Appendix for a full description of the overall methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. T. Kadowaki, K. Kasai, T. Iwatsubo, and Y. Arakawa at the Project to Create Early-Stage and Exploratory Clinical Trial Centers for providing the MRI scanning opportunities and Mika Aoki for helping with the experiment. We acknowledge financial supports provided through Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 23681033 (to N.M.), 23683011 (to M.T.), and 19002010/24220008 (to Y.M.) from MEXT, Japan, and the Nakajima Foundation (to N.M.). This work is also supported by CREST, a grant from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to T.W.), Japan Science and Technology Agency (to Y.M.), and a grant from Takeda Science Foundation (to Y.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. M.A.N. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1318570111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. The nature of human altruism. Nature. 2003;425(6960):785–791. doi: 10.1038/nature02043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1291–1298. doi: 10.1038/nature04131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rand DG, Nowak MA. Human cooperation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(8):413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milinski M, Semmann D, Bakker TC, Krambeck HJ. Cooperation through indirect reciprocity: Image scoring or standing strategy? Proc R Soc Lond B. 2001;268(1484):2495–2501. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolton GE, Katok E, Ockenfels A. Cooperation among strangers with limited information about reputation. J Public Econ. 2005;89(8):1457–1468. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seinen I, Schram A. Social status and group norms: Indirect reciprocity in a repeated helping experiment. Eur Econ Rev. 2006;50(3):581–602. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engelmann D, Fischbacher U. Indirect reciprocity and strategic reputation building in an experimental helping game. Games Econ Behav. 2009;67(2):399–407. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tennie C, Frith U, Frith CD. Reputation management in the age of the world-wide web. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14(11):482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamagishi T, Cook KS. Generalized exchange and social dilemmas. Soc Psychol Quarterly. 1993;56(4):235–248. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dufwenberg M, Gneezy U, Guth W. Direct versus indirect reciprocity: An experiment. Homo Oeconomicus. 2001;18:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartlett MY, DeSteno D. Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(4):319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molm LD, Collett JL, Schaefer DR. Building solidarity through generalized exchange: A theory of Reciprocity1. Am J Sociol. 2007;113(1):205–242. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Cooperative behavior cascades in human social networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(12):5334–5338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913149107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. The evolution of indirect reciprocity. Soc Networks. 1989;11(3):213–236. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature. 1998;393(6685):573–577. doi: 10.1038/31225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leimar O, Hammerstein P. Evolution of cooperation through indirect reciprocity. Proc Biol Sci. 2001;268(1468):745–753. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandt H, Sigmund K. The logic of reprobation: Assessment and action rules for indirect reciprocation. J Theor Biol. 2004;231(4):475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohtsuki H, Iwasa Y. How should we define goodness?—reputation dynamics in indirect reciprocity. J Theor Biol. 2004;231(1):107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton IM, Taborsky M. Contingent movement and cooperation evolve under generalized reciprocity. Proc Biol Sci. 2005;272(1578):2259–2267. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowak MA, Roch S. Upstream reciprocity and the evolution of gratitude. Proc Biol Sci. 2007;274(1610):605–609. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rankin DJ, Taborsky M. Assortment and the evolution of generalized reciprocity. Evolution. 2009;63(7):1913–1922. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwagami A, Masuda N. Upstream reciprocity in heterogeneous networks. J Theor Biol. 2010;265(3):297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delgado MR, Frank RH, Phelps EA. Perceptions of moral character modulate the neural systems of reward during the trust game. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1611–1618. doi: 10.1038/nn1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King-Casas B, et al. Getting to know you: Reputation and trust in a two-person economic exchange. Science. 2005;308(5718):78–83. doi: 10.1126/science.1108062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phan KL, Sripada CS, Angstadt M, McCabe K. Reputation for reciprocity engages the brain reward center. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(29):13099–13104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008137107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rilling J, et al. A neural basis for social cooperation. Neuron. 2002;35(2):395–405. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCabe K, Houser D, Ryan L, Smith V, Trouard T. A functional imaging study of cooperation in two-person reciprocal exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(20):11832–11835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211415698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sterzer P, Stadler C, Poustka F, Kleinschmidt A. A structural neural deficit in adolescents with conduct disorder and its association with lack of empathy. NeuroImage. 2007;37(1):335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singer T, et al. Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science. 2004;303(5661):1157–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.1093535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iacoboni M. Imitation, empathy, and mirror neurons. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:653–670. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamm C, Decety J, Singer T. Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. NeuroImage. 2011;54(3):2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banissy MJ, Kanai R, Walsh V, Rees G. Inter-individual differences in empathy are reflected in human brain structure. NeuroImage. 2012;62(3):2034–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernhardt BC, Singer T. The neural basis of empathy. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zaki J, Ochsner KN (2012) The neuroscience of empathy: Progress, pitfalls and promise. Nat Neurosci 15(5):675–680, and erratum (2013) 16:1907. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Rilling JK, et al. The neural correlates of the affective response to unreciprocated cooperation. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(5):1256–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavanna AE, Trimble MR. The precuneus: A review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 3):564–583. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mar RA. The neural bases of social cognition and story comprehension. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:103–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Overwalle F, Baetens K. Understanding others’ actions and goals by mirror and mentalizing systems: A meta-analysis. Neuroimage. 2009;48(3):564–584. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knutson B, Cooper JC. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of reward prediction. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18(4):411–417. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000173463.24758.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Doherty JP. Reward representations and reward-related learning in the human brain: Insights from neuroimaging. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14(6):769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cole MW, Schneider W. The cognitive control network: Integrated cortical regions with dissociable functions. NeuroImage. 2007;37(1):343–360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Craig ADB. How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(1):59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asch SE. Opinions and social pressure. Sci Am. 1955;193:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Izuma K. The neural basis of social influence and attitude change. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23(3):456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berns GS, et al. Neurobiological correlates of social conformity and independence during mental rotation. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(3):245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klucharev V, Hytönen K, Rijpkema M, Smidts A, Fernández G. Reinforcement learning signal predicts social conformity. Neuron. 2009;61(1):140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klucharev V, Munneke MAM, Smidts A, Fernández G. Downregulation of the posterior medial frontal cortex prevents social conformity. J Neurosci. 2011;31(33):11934–11940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1869-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andreoni J, Bernheim BD. Social image and the 50-50 norm: A theoretical and experimental analysis of audience effects. Econometrica. 2009;77(5):1607–1636. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Izuma K, Matsumoto K, Camerer CF, Adolphs R. Insensitivity to social reputation in autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(42):17302–17307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107038108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Izuma K, Saito DN, Sadato N. Processing of the incentive for social approval in the ventral striatum during charitable donation. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010;22(4):621–631. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Axelrod R (1984) The Evolution of Cooperation (Basic Books, New York)

- 52. Richerson PJ, Boyd R (2005) Not by Genes Alone: How Culture Transformed Human Evolution (Univ of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.