Significance

The establishment and maintenance of epithelial polarity relies on the tight regulation of vesicular trafficking, which ensures that apical and basolateral membrane proteins reach their designated plasma membrane domains. Here, we report the direct visualization of biosynthetic trans-endosomal trafficking of apically targeted rhodopsin in polarized epithelial cells. Our work provides novel insights into the crosstalk between biosynthetic and endocytic pathways. We demonstrate that the small GTPase Rab11a regulates sorting at apical recycling endosomes (AREs) and is also implicated in carrier vesicle docking at the apical plasma membrane. We further unveil a surprising role for dynamin-2 in the release of apical carriers from AREs. Our data indicate that trans-endosomal trafficking is indispensable for accurate and high-fidelity apical delivery.

Abstract

Emerging data suggest that in polarized epithelial cells newly synthesized apical and basolateral plasma membrane proteins traffic through different endosomal compartments en route to the respective cell surface. However, direct evidence for trans-endosomal pathways of plasma membrane proteins is still missing and the mechanisms involved are poorly understood. Here, we imaged the entire biosynthetic route of rhodopsin-GFP, an apical marker in epithelial cells, synchronized through recombinant conditional aggregation domains, in live Madin-Darby canine kidney cells using spinning disk confocal microscopy. Our experiments directly demonstrate that rhodopsin-GFP traffics through apical recycling endosomes (AREs) that bear the small GTPase Rab11a before arriving at the apical membrane. Expression of dominant-negative Rab11a drastically reduced apical delivery of rhodopsin-GFP and caused its missorting to the basolateral membrane. Surprisingly, functional inhibition of dynamin-2 trapped rhodopsin-GFP at AREs and caused aberrant accumulation of coated vesicles on AREs, suggesting a previously unrecognized role for dynamin-2 in the scission of apical carrier vesicles from AREs. A second set of experiments, using a unique method to carry out total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) from the apical side, allowed us to visualize the fusion of rhodopsin-GFP carrier vesicles, which occurred randomly all over the apical plasma membrane. Furthermore, two-color TIRFM showed that Rab11a-mCherry was present in rhodopsin-GFP carrier vesicles and was rapidly released upon fusion onset. Our results provide direct evidence for a role of AREs as a post-Golgi sorting hub in the biosynthetic route of polarized epithelia, with Rab11a regulating cargo sorting at AREs and carrier vesicle docking at the apical membrane.

Polarized epithelial cells maintain separate apical and basolateral plasma membrane (PM) domains to carry out essential vectorial absorptive and secretory functions. Tightly regulated vesicular trafficking is required to sort and target distinct sets of proteins to their respective membranes (1). Studies performed with the epithelial model cell line Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) indicate that newly synthesized membrane proteins take an indirect route to the PM. After leaving the trans-Golgi network (TGN), PM proteins first traverse endosomal compartments before reaching apical or basolateral cell surfaces (2–4). Some basolateral PM proteins traverse common recycling endosomes (CREs) where they are sorted into carrier vesicles directed toward the basolateral PM by clathrin and the clathrin adaptor AP-1B (5, 6). Alternatively, basolateral proteins can be sorted at the TGN by the clathrin adaptor AP-1A (7–9). Along the apical route it has been shown that nonraft-associated apical proteins traverse Rab11-positive apical recycling endosomes (AREs) en route to the apical PM (10). Trans-endosomal trafficking is likely to play important roles in cell physiology; for example, endosomal compartments may function as common regulatory hubs for newly synthesized and recycling PM proteins. In particular, recent data show that the small GTPase Rab11 is an important regulator of biological processes that require apical trafficking, e.g., lumen formation during epithelial tubulogenesis (11), apical secretion of discoidal/fusiform vesicles in bladder umbrella cells (12), and apical microvillus morphogenesis and rhodopsin localization in fly photoreceptors (13). However, despite the physiological importance of trans-endosomal trafficking, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unclear.

Previous studies on trans-endosomal trafficking in polarized epithelial cells have relied on pulse chase/cell fractionation protocols (3, 4) or on monitoring how ablation of an endosomal compartment affects surface arrival of a given cargo protein (4, 6, 10). These approaches, although valuable, provide limited resolution on the types of endosomes involved and on the kinetics of trans-endosomal trafficking. Elucidating the mechanisms of trans-endosomal trafficking in fully polarized epithelial cells will benefit from new methods that allow direct imaging and quantification of the transit through specific endosomal intermediates along the biosynthetic transport routes. Here, we report experiments in which we studied the biosynthetic trans-endosomal trafficking of an apical reporter, rhodopsin-GFP (14, 15), synchronized by reversible aggregation at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) through recombinant tagging with conditional aggregation domains (CADs) (16). Post-Golgi trafficking through endosomal compartments of rhodopsin-GFP, freed from the CADs through a furin-cleavage site, was traced and quantified by spinning disk confocal microscopy and its surface delivery was analyzed using a unique total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) protocol that allows live imaging of the apical PM (17).

These experiments show that rhodopsin-GFP traverses AREs during apical transport and is delivered to the apical PM by carrier vesicles that fuse randomly with the cell surface. Our data also demonstrate that the GTPases Rab11a and dynamin-2 (dyn2) play active regulatory roles in trans-ARE trafficking and apical delivery and suggest that AREs are sorting-competent organelles. To our knowledge, this is a unique direct visualization of trans-endosomal trafficking in polarized epithelial cells by live imaging.

Results and Discussion

Synchronization of Biosynthetic Trafficking Using CAD.

To study the biosynthetic route of rhodopsin in live cells, we generated a rhodopsin reporter, FM4-rhodopsin-GFP, that consists of rhodopsin tagged at the C terminus with GFP and at the N terminus with the human growth hormone signal sequence, four repeats of FM domains, and a furin cleavage site (Fig. 1A). The signal sequence ensures insertion into the ER membrane during synthesis of FM4-rhodopsin-GFP. The FM domains are variants of FK506 binding protein 12 (FKBP12) with the ability to reversibly self-aggregate into homooligomers that dissociate within minutes after addition of the membrane permeable drug AP21998 (16, 18). Through this CAD strategy, FM4-rhodopsin-GFP transiently expressed in subconfluent MDCK cells was largely retained at the ER, identified by calnexin labeling (Fig. 1B, 0 min). A few minutes after dispersal of the aggregates by AP21998, FM4-rhodopsin-GFP reached the TGN, as revealed by colocalization with the TGN marker sialyltransferase-RFP (ST-RFP) (19) (Fig. 1B, 15 min). At the TGN, furin, a protease enriched in this organelle (20), removed the FM domains through a furin cleavage site (Fig. 1 B and C), thereby allowing unencumbered post-Golgi trafficking of rhodopsin-GFP. After 120 min, we observed prominent localization of rhodopsin-GFP at the PM (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

CAD-based synchronization of a rhodopsin reporter along the biosynthetic pathway. (A) Schematic diagram showing the structure of the FM4-rhodopsin-GFP reporter. (B, Left) Schematic drawings illustrating the predicted expression pattern of FM4-rhodopsin-GFP reporter before and after release. (B, Right) Representative microscopy images of subconfluent MDCK cells transiently transfected with FM4-rhodopsin-GFP, released with AP21998 for the indicated time points, fixed, and immunostained (0 min, costaining of the ER marker calnexin; 15 min, coimaging of stably expressed ST-RFP; and 120 min, costaining of nuclei with DAPI). (C) Western blot of cell lysates from MDCK cells transiently transfected with FM4-rhodopsin-GFP and treated with AP21998 for the indicated times. An anti-GFP antibody was used to detect FM4-rhodopsin-GFP and furin-cleaved rhodopsin-GFP. Actin was also probed as an internal loading control. (D) A 3D representation of the distribution of FM4-rhodopsin-GFP in two neighboring polarized MDCK cells 15, 30, 45, and 120 min after addition of AP21998. Note the head “cap” appearance of rhodopsin-GFP on the apical surfaces at 120 min.

AP21998 also efficiently induced the release of FM4-rhodopsin-GFP from the ER in fully polarized MDCK cells grown on Transwell filters. Using time-lapse spinning disk confocal microscopy, we observed rhodopsin-GFP reaching the apical surface with high fidelity (Fig. 1D and Movie S1), through a vectorial route that does not involve transcytosis from the basolateral PM, as previously reported (14, 15).

Rhodopsin Traverses Rab11a-Positive Endosomes en Route to the Apical PM.

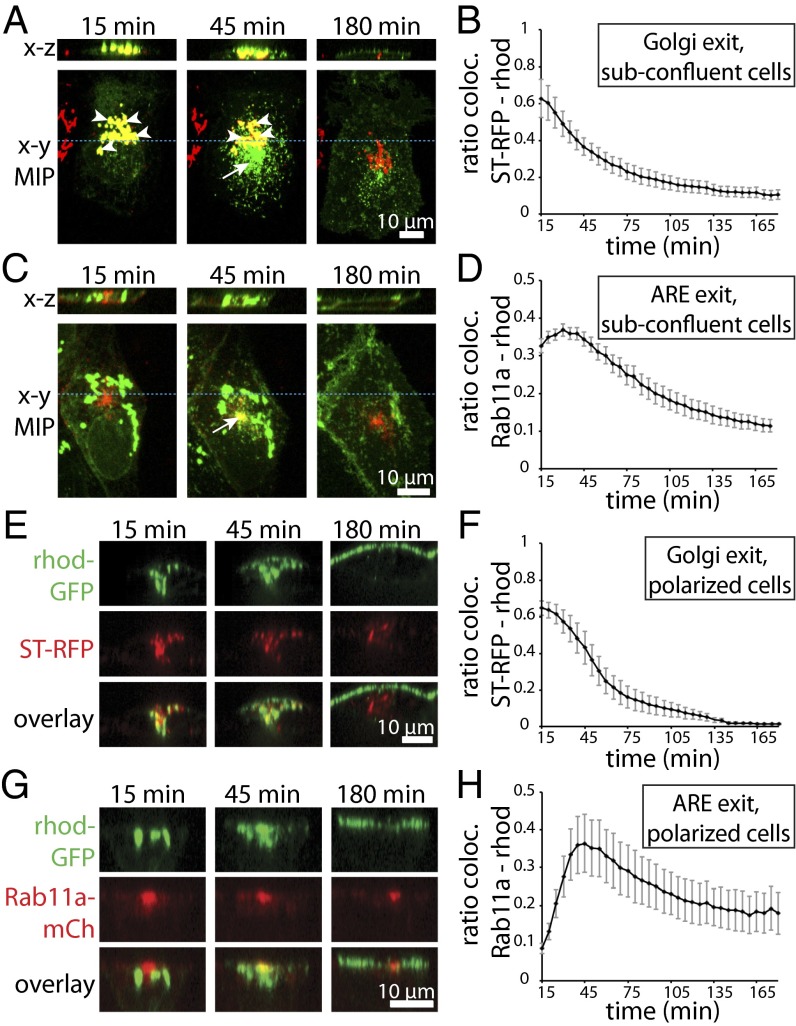

We first characterized by time-lapse imaging the trafficking of transiently transfected FM4-rhodopsin-GFP across the TGN in subconfluent MDCK cells stably expressing the TGN marker ST-RFP (Fig. 2A). Because it takes ∼15 min to set up the measurement at the microscope after addition of AP21998, a large fraction of FM4-rhodopsin-GFP was already present at the TGN when live imaging started (T = 15 min). Quantification of the time-lapse experiments demonstrated a monotonic decline in the colocalization of FM4-rhodopsin-GFP with ST-RFP (Fig. 2B). After leaving the TGN, rhodopsin-GFP transiently accumulated at a ST-RFP-negative perinuclear compartment (Fig. 2A, arrow, 45 min time point) before reaching the PM. To address whether or not this post-Golgi intermediate compartment represents Rab11a-positive recycling endosomes, we established an MDCK cell line stably expressing Rab11a-mCherry and observed the trafficking of FM4-rhodopsin-GFP in these cells plated at subconfluent density (Fig. 2C). Indeed, we observed a temporary but significant colocalization of rhodopsin-GFP with Rab11a-mCherry that peaked ∼30 min after AP21998 addition (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Direct visualization and quantification of the biosynthetic trafficking route of FM4-rhodopsin-GFP. (A–D) FM4-rhodopsin-GFP (green) was transiently transfected to subconfluent MDCK cells stably expressing either ST-RFP (A, red) or Rab11a-mCherry (C, red). After addition of AP21998 (defined as t = 0 min), cells were transferred to the microscope and imaging was initiated. Representative images taken from the time-lapse recordings are shown in A and C. (Lower) Maximum intensity projection (MIP) along z; (Upper) An x–z section. The blue lines indicate the position of the displayed x–z sections. (A, arrowheads) Rhodopsin-GFP colocalizing with ST-RFP. (A, arrow) Rhodopsin-GFP signal at an intermediate compartment outside TGN. (C, arrow) Rhodopsin-GFP colocalizing with Rab11a-mCherry-positive perinuclear endosomes. (B and D) The ratio of rhodopsin-GFP colocalizing with ST-RFP (B) or Rab11a-mCherry (D) in subconfluent cells plotted over time after addition of AP21998. (E–H) FM4-rhodopsin-GFP was transiently transfected to polarized MDCK cells stably expressing ST-RFP (E) or Rab11a-mCherry (G). After addition of AP21998 (t = 0 min), cells were transferred to the microscope and imaging was initiated. Representative sections along the apico–basal axis of a cell are shown. (F and H) The ratio of rhodopsin-GFP colocalizing with ST-RFP (F) or Rab11a-mCherry (H) in polarized cells plotted over time after addition of AP21998. All quantification data shown in B, D, F, and H are the averages obtained from more than six individual cells; error bars represent SEM.

In polarized MDCK cells, Rab11a localizes to AREs, which, consistent with previous findings (21), appeared as a subapical spot constituted by a cluster of vesicles around the centrosome (Fig. 2G). Live imaging experiments in fully polarized MDCK cells showed that after release from the ST-RFP–labeled TGN, rhodopsin-GFP transiently colocalized with Rab11a-labeled AREs before reaching the apical PM (Fig. 2 E–H). The slight difference in the kinetics of ARE-exit between subconfluent and polarized MDCK cells is probably due to cytoskeletal rearrangements and morphological changes upon cell polarization, which alter the transport tracks and relative distances between the involved compartments.

Thus, our live-imaging experiments show that in both subconfluent and polarized MDCK cells, newly synthesized rhodopsin-GFP colocalizes successively with ST-RFP and Rab11a-mCherry before its appearance at the PM. This clearly indicates that after exiting the TGN, rhodopsin-GFP transits through Rab11a-positive endosomes en route to the apical surface.

Functional Rab11 Is Required for Apical Delivery of Rhodopsin from ARE.

In pilot steady-state localization experiments in polarized MDCK cells, we found that coexpression of untagged rhodopsin with GFP-tagged Rab11aS25N, a dominant negative (DN) mutant Rab11a (DN-Rab11a-GFP), but not with wild type (WT)-Rab11a-GFP, resulted in mislocalization of rhodopsin to the basolateral PM and to intracellular compartments (Fig. S1). Subsequent live imaging experiments of FM-rhodopsin-GFP in polarized MDCK cells consistently showed that DN-Rab11a-mCherry induced mislocalization of rhodopsin-GFP to both the basolateral PM (Fig. S2, arrows) and intracellular compartments.

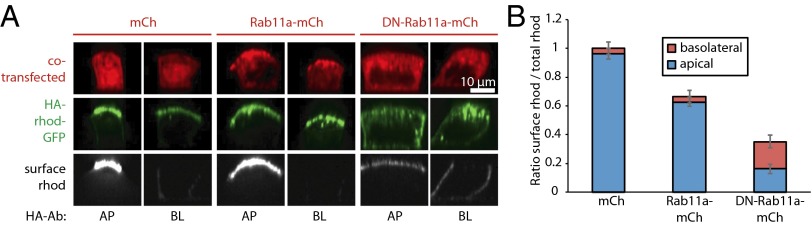

To precisely quantify the surface delivery of rhodopsin-GFP, we generated an FM4-HA-rhodopsin-GFP reporter. The hemagglutinin (HA) tag was inserted between the furin cleavage site and rhodopsin’s N terminus, which is exposed to the extracellular space, thus allowing specific detection and quantification of PM-localized HA-rhodopsin-GFP using an anti-HA antibody. We first validated the assay in subconfluent cells (Fig. S3). We then used the assay to measure the rhodopsin surface delivery in polarized MDCK cells. To this end, we transiently transfected polarized MDCK cells grown on filters with FM4-HA-rhodopsin-GFP together with either Rab11a-mCherry, DN-Rab11a-mCherry, or mCherry as a control. Three hours after release, HA antibodies were added to either the apical or basal side of live cells to access HA-rhodopsin-GFP that was delivered to the respective surface domain. Immunolabeling (Fig. 3A) and subsequent quantitative analyses (Fig. 3B) showed that HA-rhodopsin-GFP was predominantly delivered to the apical surface in control cells coexpressing mCherry. Coexpression of Rab11a-mCherry preserved apical targeting of HA-rhodopsin-GFP (Fig. 3A); albeit we observed a slight decrease in apical surface delivery rate (Fig. 3B), probably due to a weak inhibitory effect caused by the transient overexpression of Rab11a-mCherry. By contrast, coexpression of DN-Rab11a-mCherry significantly reduced apical surface delivery of HA-rhodopsin-GFP (to ∼16% compared with mCherry coexpressing control cells; Fig. 3B), which was accompanied by an increase in intracellular accumulation (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, coexpression of DN-Rab11a-mCherry also caused an approximately fivefold increase in basolateral delivery of HA-rhodopsin-GFP (Fig. 3 A and B).

Fig. 3.

Rab11a-positive AREs play a pivotal role in apical delivery and sorting of rhodopsin-GFP. (A) FM4-HA-rhodopsin-GFP and either mCherry, Rab11a-mCherry, or DN-Rab11a-mCherry were transiently transfected to polarized MDCK cells. After addition of AP21998 for 3 h, cells were incubated for 1 h with Cy5-conjugated anti-HA antibody from the apical (AP) or basolateral (BL) side to label surface HA-rhodopsin-GFP. Representative sections along the apico–basal axis of individual cells are shown. Note that all images have been scaled equally to allow direct comparison. Thus, in some images surface rhodopsin signal is very dim, because surface rhodopsin signal levels vary from 95% to below 5% (Fig. 3B). (B) Quantification of HA-rhodopsin surface arrival in cells cotransfected with either mCherry, Rab11a-mCherry, or DN-Rab11a-mCherry. The histogram shows the mean ratio of surface rhodopsin versus total rhodopsin calculated from 40 individual cells per condition; error bars represent SEM.

To control for the specificity of Rab11a’s involvement in rhodopsin biosynthetic trafficking, we inhibited Rab5, a resident of early endosomes, using a similar approach (22). As expected, overexpression of mCherry-tagged DN mutant Rab5 (Rab5S34N) did not interfere with apical targeting of rhodopsin-GFP in polarized MDCK cells (Fig. S4A). As an additional control, we tested the effect of DN-Rab11a-mCherry on the targeting of neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), a basolateral marker in MDCK cells (23). Overexpression of DN-Rab11a-mCherry did not affect the basolateral targeting of FM4-NCAM-GFP (Fig. S4B), indicating that the overall polarity of cells was not compromised in our experimental setup.

Taken together, the experiments described in this section demonstrate that Rab11a regulates apical protein targeting from AREs to the apical PM and suggest that AREs are sorting-competent organelles.

Dyn2 Is Required for the Exit of Rhodopsin from AREs.

The GTPase dynamin plays an important role in clathrin-dependent and -independent endocytosis from the PM and in various actin-regulated processes (24). The ubiquitous isoform dyn2 has also been shown to mediate the scission of carrier vesicles from the TGN (25, 26); in subconfluent MDCK cells, inhibition of dyn2 blocks the TGN release of vesicles carrying the apical marker p75 (27). Although perturbing dyn2 function has also been shown to inhibit the surface delivery of p75 in polarized MDCK cells (28), the subcellular compartment at which p75 transport is blocked has not been examined. To date, the exact function of dyn2 in surface protein delivery in polarized epithelial cells remains unclear.

Previous reports showed that dynamin/shibire localizes to Rab11-positive endosomes in Drosophila (29). Hence, we investigated whether dyn2 is involved in apical trafficking of rhodopsin in polarized MDCK cells using the FM4-rhodopsin-GFP synchronization approach. We found that coexpression of WT-dyn2-RFP did not affect the apical surface targeting of rhodopsin-GFP (Fig. 4A). By contrast, DN-dyn2-mCherry (dyn2 with K44A mutation) drastically reduced the surface appearance of cotransfected rhodopsin-GFP (Fig. 4 B and C). Note that under the same expression conditions, DN-dyn2 did not detectably disturb overall cell polarity (Fig. S5). To corroborate our findings via the dominant negative approach, we also showed that the cell-permeable dynamin inhibitor dynasore (30) was able to block the apical delivery of rhodopsin-GFP in a dosage-dependent manner (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Dyn2 is required for rhodopsin-GFP exit from AREs. (A) After addition of AP21998 for 3 h, polarized MDCK cells expressing FM4-rhodopsin-GFP and dyn2-RFP were fixed and imaged. Representative sections along the apico–basal axis of three individual cells are shown. (B) Polarized cells expressing FM4-rhodopsin-GFP (green) and DN-dyn2-mCherry (false color blue) were fixed and immunostained for Rab11a (red) and giantin (magenta) 3 h post-AP21998 addition. Representative sections along the apico–basal axis of three individual cells are shown. The white arrows point to rhodopsin-GFP retained at Rab11a-positive AREs. Also see Fig. S6A for the apical x–y sections of a larger area around “cell 1.” (C) After addition of AP21998 for 3 h, polarized MDCK cells expressing FM4-HA-rhodopsin-GFP and either mCherry or DN-dyn2-mCherry were incubated for 1 h with Cy5-conjugated anti-HA antibody from the apical or basolateral side to label surface HA-rhodopsin-GFP. In the experiments using dynasore (ds), the indicated concentration of dynasore was added during AP21998 incubation and anti-HA antibody binding. The histogram shows the mean ratio of surface rhodopsin versus total rhodopsin calculated from 30 individual cells per condition; error bars represent SEM. (D and E) Representative electron micrographs of polarized MDCK cells expressing WT-dyn2 (D) or DN-dyn2 (E) that were labeled with anti-Rab11a antibody followed by 5 nm gold-conjugated secondary antibody (arrowheads). Arrows point to coated structures on subapical tubules that are positive for Rab11a.

Of great interest, in DN-dyn2–expressing cells rhodopsin-GFP was retained predominantly at Rab11a-positive AREs (68 ± 2%, n = 5) (Fig. 4B, arrows), rather than at the giantin-labeled Golgi apparatus (3 ± 1%, n = 5) (Fig. 4B and Fig. S6A). Similar results were obtained using cells coexpressing DN-dyn2-GFP and FM4-rhodopsin-mCherry (i.e., by switching the fluorescent tags of rhodopsin and dyn2) (Fig. S6B). Furthermore, shRNA-mediated knockdown of dyn2 also interfered with PM targeting of rhodopsin (Fig. S6 C and D). We found that a small fraction of either ectopically expressed (Fig. S7A) or endogenous dyn2 (Fig. S7 A and B) was in close vicinity to Rab11a-labeled AREs, consistent with the idea that dyn2 is transiently recruited to AREs to participate in the scission of vesicles.

We subsequently performed ultrastructural analyses on polarized MDCK cells expressing dyn2 variants. Expression of DN-dyn2, but not WT-dyn2, induced aberrant accumulation of coated pits on the PM (Fig. S7 D and F vs. C and E), consistent with a role for dyn2 in PM endocytosis (24, 31). Furthermore, DN-dyn2 expression increased the occurrence of coated structures attached to Rab11a-immunogold–labeled subapical tubules, which likely represent AREs (Fig. 4 E vs. D). By including ruthenium red (a dye for assessing cell surface accessibility) (31) during fixation, we found that in DN-dyn2–expressing cells coated structures frequently appeared on ruthenium red-positive tubules emanating from the PM (Fig. S7F, white arrowhead), whereas ruthenium red-negative ARE-like structures bearing coats were found in the subapical cytosol (Fig. S7F, white arrows). These results support the view that DN-dyn2 inhibits scission of post-ARE carriers. Collectively, these findings provide strong evidence that dyn2 regulates the release of apical vesicular carriers from AREs, instead of the TGN, in polarized epithelial cells.

Rab11a Is Present on Rhodopsin Vesicles Undergoing Apical Membrane Fusion: A Role for Rab11a in Vesicle Docking.

To image the progression of rhodopsin-GFP from Rab11a-positive AREs to the apical PM, we used a recently developed biochip that enables TIRFM at the apical PM of polarized epithelial cells (17). Briefly, after a polarized monolayer of MDCK cells is grown on the biochip, the whole chip is inverted and placed on a glass coverslip on a microscope. The chip allows approaching the cells to the glass surface with submicrometer precision so that the apical PM can be imaged using selective excitation via a shallow (∼200 nm) evanescent wave (32). This technique allows observation of individual apical vesicle fusion events, including the subsequent diffusive spreading of cargo proteins (17). Indeed, starting at ∼1 h after release from the ER, we observed vesicles bearing rhodopsin-GFP fusing with the apical PM. A representative fusion event is shown in Fig. 5A. The mean intensity (IM) of rhodopsin-GFP measured in a 1 µm × 1 µm region centered at the fusion site was determined as a measure for the amount of rhodopsin-GFP delivered by the vesicle during the fusion process (Fig. 5B). IM showed a sharp increase at the onset of fusion, because the vesicle entered regions with higher excitation intensity within the exponentially declining evanescent wave when it was moved closer to the PM during priming (33, 34). The sharp increase in IM was followed by an exponential decay phase, which is due to diffusive spreading of rhodopsin-GFP along the apical PM. Interestingly, in some fusion events rhodopsin-GFP underwent circularly symmetrical spreading (Fig. 5A), whereas in other fusion events, the diffusion was asymmetrical (Fig. S8A), likely representing diffusion into adjacent microvilli. Furthermore, rhodopsin-GFP vesicle fusion events were rather randomly distributed throughout the apical PM (Fig. S8B), indicating that there was no preferred fusion site.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of fusion events of rhodopsin-GFP and Rab11a-mCherry–bearing vesicles at the apical PM. (A) TIRFM time-lapse images of a vesicle-bearing rhodopsin-GFP (Upper) and Rab11a-mCherry (Lower) fusing with the apical PM of a polarized MDCK cell. To enhance the visibility of Rab11a-mCherry signal, the same non–time-depend uneven background has been subtracted from all Rab11a-mCherry time-lapse images. The onset of the fusion event is marked with white arrows. (B) Time course of the mean intensity measured at a 1 µm × 1 µm region centered at the fusion site for the rhodopsin-GFP signal and Rab11a-mCherry signal from the fusion event shown in Fig. 5A.

Importantly, all rhodopsin-GFP vesicle fusion events also showed a weak, but well-defined, signal of Rab11a-mCherry (Fig. 5A), indicating that rhodopsin-GFP-bearing vesicles undergoing fusion also carried Rab11a-mCherry. The time constant of the exponential decay phase for rhodopsin-GFP was significantly larger than the time constant for Rab11a-mCherry (2.26 ± 0.08 s vs. 0.89 ± 0.17 s, respectively, for the fusion event shown in Fig. 5B). This indicates that Rab11a-mCherry left the fusion site much faster than rhodopsin-GFP. In addition, we observed the same behavior of rhodopsin-GFP and Rab11a-mCherry during vesicle fusion with the PM using classic TIRFM at the adherent membrane of subconfluent MDCK cells (Fig. S9A). These experiments showed that all rhodopsin-GFP–bearing vesicles undergoing fusion also carried Rab11a-mCherry (100%, n = 20; Fig. S9A), suggesting that Rab11a plays a role in the docking of rhodopsin vesicles at the apical PM. Consistent with several recent studies that showed that Rab11a and its isoform Rab11b tend to participate in trafficking of different cargoes (11, 35–37), we found that only a minor fraction of fusion events exhibited a detectable Rab11b-mCherry signal (20%, n = 20; Fig. S9B).

Conclusions

Our current knowledge of vectorial protein trafficking in polarized epithelia has been greatly advanced by the investigation of exogenously expressed reporter molecules, which are predominantly delivered to either apical or basolateral domains (4). Although not endogenously expressed, studying rhodopsin’s transport in MDCK cells has led to the discovery of a unique cytoplasmic targeting signal and dynein’s involvement in apical targeting (14, 15). Here, using a combination of CAD-mediated synchronization of transport with high-resolution microscopy methods, we were able to directly visualize and quantify trans-endosomal trafficking of rhodopsin-GFP in polarized epithelial cells. Our results demonstrate that rhodopsin transits obligatorily through AREs, where it is sorted by a Rab11a-mediated mechanism into carrier vesicles, which are released by dyn2. This provides a mechanistic explanation for rhodopsin’s mislocalization in fly photoreceptors in which Rab11 has been silenced by RNAi (13). We also show, using apical TIRFM, that rhodopsin-bearing vesicles fusing with the apical PM also carry Rab11a, which is quickly released after fusion onset, consistent with a role of Rab11a in vesicle docking. In support of this proposal, a role for Rab11a in regulating vesicle fusion at the PM has recently been proposed in the endosomal recycling of langerin in nonpolarized cells (38).

Our results add substantial support to the concept that AREs are a central intermediate compartment along multiple intracellular trafficking routes, including transcytosis in both directions (21, 29), biosynthetic basolateral protein targeting (39), and biosynthetic apical PM targeting (ref. 10 and this paper). Future work will be needed to define and dissect specific roles of various Rab11 effectors (e.g., Rab11FIP1-5, Sec15, and Rabin8 (11, 40, 41) in distinct trafficking pathways regulated by Rab11 and AREs.

In addition, we demonstrate a previously undescribed function of dyn2 in the release of biosynthetic apical cargo from AREs. The defective fission of coated vesicles from AREs caused by DN-dyn2 strongly argues that dyn2 has a physiologically relevant role in ARE trafficking, which is not only restricted to the transport of rhodopsin. Further studies are needed to identify a cognate cargo(es) as well as the composition of coats. Finally, dyn2 is not required for the surface delivery of basolateral markers like VSV-G protein (28). The scission of carrier vesicles coated by clathrin and AP-1, which have been implicated in the basolateral sorting of PM proteins (8, 19), is also dyn2 independent (42). Hence, it will be interesting to test whether or not dyn2 is uniquely required for apical PM protein targeting.

Materials and Methods

Detailed materials and methods are available in SI Materials and Methods. Briefly, for spinning disk confocal microscopy, MDCK II cells were cultured on Transwell filters for 4 d and transfected with the indicated plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Six hours later, the filters were removed and placed with the cells pointing downward on a glass coverslip on an inverted microscope (Zeiss; Axio Observer Z1). Release of FM4-rhodopsin-GFP from the ER was initiated by addition of 5 μM AP21998 (ARIAD).

The procedure for apical TIRFM by means of a biochip has been described previously (17). Briefly, MDCK II cells were grown on a fibronectin-coated cell culture area on top of the biochip for 4 d before transfection with the indicated plasmids. After addition of 5 μM AP21998, the biochip was placed upside down on a BSA-coated glass slide on an inverted microscope (Zeiss; Axiovert 200). The biochip enabled precise positioning of the cells’ apical PM to the evanescent wave, which allowed imaging the fusion of rhodopsin carrier vesicles with the apical PM by apical TIRFM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pietro De Camilli, Michael Butterworth, Jeffrey Pessin, and Tim McGraw for sharing reagents. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants EY08538 and GM34107 and by the Margaret Dyson Foundation (to E.R-B.), and NIH Grants EY11307 and EY016805 and Research To Prevent Blindness (to C.-H.S.). W.R. is supported by the Excellence Initiative of the German Research Foundation (EXC 294), a grant from the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of Baden-Württemberg (Az: 33-7532.20), and a starting grant of the European Research Council (Programme “Ideas,” call identifier: ERC-2011-StG 282105). J.M.C.-G. was supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization fellowship. R.T. was supported in part by grants from the Austrian Science Fund (PhD Program Molecular Bioanalytics), the Government of Upper Austria, the European Fund for Regional Development (Hochsensitive Analysemethoden für die Untersuchung von biologischen Proben), and a Marshall Plan Scholarship to carry out this research project in E.R-B.’s laboratory during his PhD studies.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. K.E.M. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1304168111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rodriguez-Boulan E, Kreitzer G, Müsch A. Organization of vesicular trafficking in epithelia. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(3):233–247. doi: 10.1038/nrm1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cramm-Behrens CI, Dienst M, Jacob R. Apical cargo traverses endosomal compartments on the passage to the cell surface. Traffic. 2008;9(12):2206–2220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez A, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Clathrin and AP1B: Key roles in basolateral trafficking through trans-endosomal routes. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(23):3784–3795. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisz OA, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Apical trafficking in epithelial cells: signals, clusters and motors. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 23):4253–4266. doi: 10.1242/jcs.032615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gan Y, McGraw TE, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The epithelial-specific adaptor AP1B mediates post-endocytic recycling to the basolateral membrane. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(8):605–609. doi: 10.1038/ncb827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ang AL, et al. Recycling endosomes can serve as intermediates during transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane of MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 2004;167(3):531–543. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carvajal-Gonzalez JM, et al. Basolateral sorting of the coxsackie and adenovirus receptor through interaction of a canonical YXXPhi motif with the clathrin adaptors AP-1A and AP-1B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(10):3820–3825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117949109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gravotta D, et al. The clathrin adaptor AP-1A mediates basolateral polarity. Dev Cell. 2012;22(4):811–823. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo Y, Zanetti G, Schekman R. A novel GTP-binding protein-adaptor protein complex responsible for export of Vangl2 from the trans Golgi network. Elife. 2013;2:e00160. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cresawn KO, et al. Differential involvement of endocytic compartments in the biosynthetic traffic of apical proteins. EMBO J. 2007;26(16):3737–3748. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant DM, et al. A molecular network for de novo generation of the apical surface and lumen. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(11):1035–1045. doi: 10.1038/ncb2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khandelwal P, et al. Rab11a-dependent exocytosis of discoidal/fusiform vesicles in bladder umbrella cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(41):15773–15778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805636105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satoh AK, O’Tousa JE, Ozaki K, Ready DF. Rab11 mediates post-Golgi trafficking of rhodopsin to the photosensitive apical membrane of Drosophila photoreceptors. Development. 2005;132(7):1487–1497. doi: 10.1242/dev.01704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuang J-Z, Sung C-H. The cytoplasmic tail of rhodopsin acts as a novel apical sorting signal in polarized MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;142(5):1245–1256. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.5.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh TY, Peretti D, Chuang JZ, Rodriguez-Boulan E, Sung CH. Regulatory dissociation of Tctex-1 light chain from dynein complex is essential for the apical delivery of rhodopsin. Traffic. 2006;7(11):1495–1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivera VM, et al. Regulation of protein secretion through controlled aggregation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 2000;287(5454):826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thuenauer R, et al. A PDMS-based biochip with integrated sub-micrometre position control for TIRF microscopy of the apical cell membrane. Lab Chip. 2011;11(18):3064–3071. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20458k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaiswal JK, Rivera VM, Simon SM. Exocytosis of post-Golgi vesicles is regulated by components of the endocytic machinery. Cell. 2009;137(7):1308–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deborde S, et al. Clathrin is a key regulator of basolateral polarity. Nature. 2008;452(7188):719–723. doi: 10.1038/nature06828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simmen T, Nobile M, Bonifacino JS, Hunziker W. Basolateral sorting of furin in MDCK cells requires a phenylalanine-isoleucine motif together with an acidic amino acid cluster. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(4):3136–3144. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Apodaca G, Katz LA, Mostov KE. Receptor-mediated transcytosis of IgA in MDCK cells is via apical recycling endosomes. J Cell Biol. 1994;125(1):67–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(8):513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Gall AH, Powell SK, Yeaman CA, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The neural cell adhesion molecule expresses a tyrosine-independent basolateral sorting signal. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(7):4559–4567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson SM, De Camilli P. Dynamin, a membrane-remodelling GTPase. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(2):75–88. doi: 10.1038/nrm3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones SM, Howell KE, Henley JR, Cao H, McNiven MA. Role of dynamin in the formation of transport vesicles from the trans-Golgi network. Science. 1998;279(5350):573–577. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu YW, Surka MC, Schroeter T, Lukiyanchuk V, Schmid SL. Isoform and splice-variant specific functions of dynamin-2 revealed by analysis of conditional knock-out cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(12):5347–5359. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreitzer G, Marmorstein A, Okamoto P, Vallee R, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Kinesin and dynamin are required for post-Golgi transport of a plasma-membrane protein. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(2):125–127. doi: 10.1038/35000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonazzi M, et al. Differential roles of BARS and dynamin in the export of VSVG and p75 from the TGN. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:570–580. doi: 10.1038/ncb1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelissier A, Chauvin JP, Lecuit T. Trafficking through Rab11 endosomes is required for cellularization during Drosophila embryogenesis. Curr Biol. 2003;13(21):1848–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macia E, et al. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell. 2006;10(6):839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marks B, et al. GTPase activity of dynamin and resulting conformation change are essential for endocytosis. Nature. 2001;410(6825):231–235. doi: 10.1038/35065645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaiswal JK, Simon SM. Imaging single events at the cell membrane. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(2):92–98. doi: 10.1038/nchembio855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmoranzer J, Goulian M, Axelrod D, Simon SM. Imaging constitutive exocytosis with total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. J Cell Biol. 2000;149(1):23–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toomre D, Steyer JA, Keller P, Almers W, Simons K. Fusion of constitutive membrane traffic with the cell surface observed by evanescent wave microscopy. J Cell Biol. 2000;149(1):33–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silvis MR, et al. Rab11b regulates the apical recycling of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in polarized intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(8):2337–2350. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butterworth MB. Regulation of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) by membrane trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802(12):1166–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lapierre LA, et al. Rab11b resides in a vesicular compartment distinct from Rab11a in parietal cells and other epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2003;290(2):322–331. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gidon A, et al. A Rab11A/myosin Vb/Rab11-FIP2 complex frames two late recycling steps of langerin from the ERC to the plasma membrane. Traffic. 2012;13(6):815–833. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lock JG, Stow JL. Rab11 in recycling endosomes regulates the sorting and basolateral transport of E-cadherin. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(4):1744–1755. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang XM, Ellis S, Sriratana A, Mitchell CA, Rowe T. Sec15 is an effector for the Rab11 GTPase in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(41):43027–43034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hales CM, et al. Identification and characterization of a family of Rab11-interacting proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(42):39067–39075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kural C, et al. Dynamics of intracellular clathrin/AP1- and clathrin/AP3-containing carriers. Cell Rep. 2012;2(5):1111–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.