Significance

Dephosphorylation of the tumor-suppressor retinoblastoma protein (Rb) leads to its activation. Our structure of the protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) nuclear targeting subunit (PNUTS):PP1 holoenzyme reveals how this reaction is regulated: PNUTS and Rb compete for an identical binding site on PP1. Because PP1 binds PNUTS 400-fold more strongly than Rb, when PNUTS is present, Rb is not dephosphorylated. However, when PNUTS levels are reduced, PP1 binds and dephosphorylates Rb, leading to its activation. This structure also led to the identification of additional common PP1 binding motifs, allowing us to predict how a quarter of the known PP1 regulators bind to PP1. This result is a key advance for understanding the regulation of PP1, which controls >50% of all dephosphorylation reactions.

Keywords: nuclear phosphatases, enzyme regulation, enzyme specificity, X-ray crystal structure, nuclear magnetic resonance

Abstract

The serine/threonine protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) dephosphorylates hundreds of key biological targets by associating with nearly 200 regulatory proteins to form highly specific holoenzymes. However, how these proteins direct PP1 specificity and the ability to predict how these PP1 interacting proteins bind PP1 from sequence alone is still missing. PP1 nuclear targeting subunit (PNUTS) is a PP1 targeting protein that, with PP1, plays a central role in the nucleus, where it regulates chromatin decondensation, RNA processing, and the phosphorylation state of fundamental cell cycle proteins, including the retinoblastoma protein (Rb), p53, and MDM2. The molecular function of PNUTS in these processes is completely unknown. Here, we show that PNUTS, which is intrinsically disordered in its free form, interacts strongly with PP1 in a highly extended manner. Unexpectedly, PNUTS blocks one of PP1’s substrate binding grooves while leaving the active site accessible. This interaction site, which we have named the arginine site, allowed us to define unique PP1 binding motifs, which advances our ability to predict how more than a quarter of the known PP1 regulators bind PP1. Additionally, the structure shows how PNUTS inhibits the PP1-mediated dephosphorylation of critical substrates, especially Rb, by blocking their binding sites on PP1, insights that are providing strategies for selectively enhancing Rb activity.

Protein phosphatase 1 (PP1; ∼38.5 kDa), a single-domain protein, is the most widely expressed and abundant serine/threonine phosphatase (1). By dephosphorylating a variety of protein substrates, PP1 regulates diverse biological processes, including protein synthesis, muscle contraction, carbohydrate metabolism, neuronal signaling and, of specific interest for this work, cell-cycle progression. Although the intrinsic substrate specificity of PP1 is very low, by interacting with regulatory proteins (∼200 biochemically confirmed PP1 interactors), PP1 achieves high specificity (2–5). The majority of PP1 regulators and some substrates bind PP1 via a primary PP1-binding motif, the RVxF motif, which binds to a hydrophobic groove on PP1 ∼20 Å distal from its catalytic center (6). Outside of the RVxF motif, PP1 regulatory proteins mostly lack any apparent sequence similarity. Thus, additional interaction sites, such as the SILK (7), the MyPhoNE (8), and the recently identified ΦΦ motif (9) can only be identified by structural analysis, a major challenge for a comprehensive understanding of PP1 regulation. Only when the primary sequences of PP1 regulators are correlated with specific PP1 binding modes and activities will the PP1 interactome, and the biological processes it regulates, become a viable drug target for the multitude of PP1-associated diseases, such as multiple cancers.

One of the key PP1 regulatory targeting proteins in the nucleus, in addition to nuclear inhibitor of PP1 (NIPP1) and Repo-man, is the PP1 nuclear targeting subunit (10) [PNUTS; also known as p99 (11)/FB19 (12)/CAT53 (13); 872 aa, 92.8 kDa; SI Appendix, Fig. S1]. PNUTS is ubiquitously expressed, with high protein levels found in the brain (10, 11), and colocalizes with chromatin during telophase (10). PNUTS itself is a multidomain protein defined by a central PP1-binding domain, where residues 398TVTW401 constitute the canonical PP1 RVxF interaction motif (14). It also has an N-terminal TFS2N domain that interacts with the DNA binding protein Tox4/LCP1, a C-terminal RGG domain that mediates RNA binding and, in its extreme C terminus, a putative Zn2+ finger domain (10).

The PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme plays a central role in multiple nuclear processes, including chromatin decondensation (15), the DNA damage response (16), and cardiomyocyte apoptosis (17). Importantly, PNUTS also directly regulates the activities of two key tumor suppressors: the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein, which controls cell proliferation, and p53, a master regulator of apoptosis in response to cellular stress (18, 19). Specifically, PNUTS inhibits PP1 activity toward Rb, thereby inhibiting the PP1-mediated Rb dephosphorylation that is required for mitotic exit. PNUTS also inhibits the PP1-mediated dephosphorylation of Ser15 on p53 and Ser395 on MDM2, which results in an increase in p53 stability and transcriptional activity and an enhancement of MDM2 degradation, respectively (19). PNUTS has also been shown to associate with RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) at active sites of transcription and enhance the dephosphorylation of the RNAPII C-terminal domain (CTD) residue Ser5 (20, 21). Remarkably, despite its role in these processes, the molecular function of PNUTS is still largely uncharacterized. In addition, with the exception of RNAPII CTD, there are no confirmed endogenous substrates of the PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme, and although PNUTS clearly enhances the phosphorylation of Rb, p53, and MDM2, it is not known whether this enhancement is because PNUTS is a direct inhibitor of PP1 activity (i.e., a protein that binds and blocks the PP1 active site) or because PNUTS binding disrupts the interaction of these substrates with PP1.

Here, we used NMR spectroscopy, X-ray crystallography, and biochemistry to elucidate, at a molecular level, how PNUTS binds PP1 and directs its specificity. The crystal structure of the PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme (here, holoenzyme refers to the complex between PP1 and the PP1-binding domain of PNUTS) shows that PNUTS, which is an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) in its free state, uses both the RVxF motif and the recently identified ΦΦ motif binding pockets to bind PP1. Unexpectedly, PNUTS, like spinophilin (22), also binds the PP1 C-terminal groove, resulting in the definition of an additional common PP1 regulator binding pocket. A structure-based alignment of PP1 holoenzymes led to the description of two unique extended PP1 binding motifs in PP1 regulators, which were then identified in more than 20% of known PP1 regulators. Together, this work advances our ability to predict how other PP1 regulators bind PP1 and provides critical insights into how PNUTS inhibits the PP1-mediated dephosphorylation of substrates, especially p53, MDM2, and Rb.

Results

PNUTS Residues 394–433 Constitute the PNUTS PP1 Binding Domain.

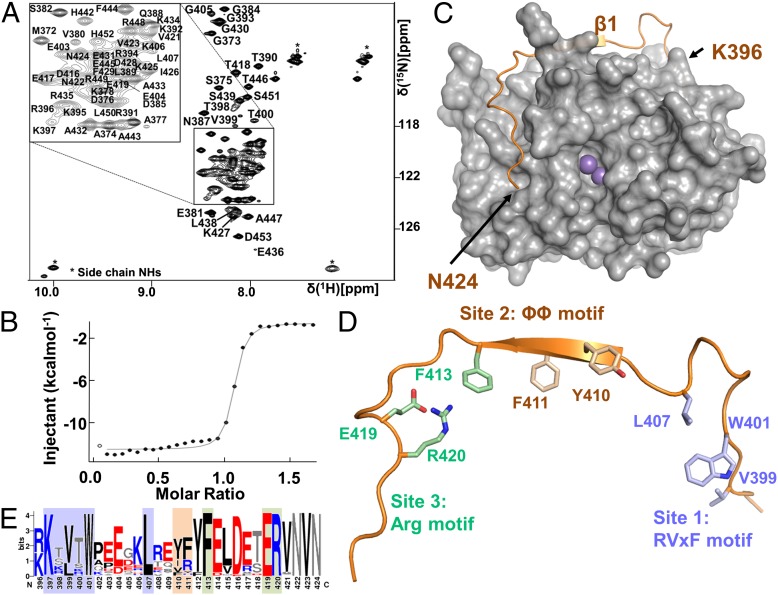

PP1 pull-down and phosphorylase a inhibition assays showed that PP1 binds PNUTS between residues 309 and 453 (11, 14). To precisely define the residues that directly interact with PP1, we used a combination of NMR spectroscopy and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). A 2D [1H,15N] heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum of PNUTS309–433 showed that PNUTS, like most PP1 regulatory proteins (3, 22–25), is an IDP based on the significantly limited chemical-shift dispersion in the 1HN dimension, an observation consistent with PNUTS’s high temperature stability (80 °C). Interestingly, the spectrum contained many more peaks than expected because of significant proline cis/trans isomerization (18 proline residues are present in PNUTS309–433). Thus, a detailed NMR analysis was problematic and only a ∼50% sequence-specific backbone assignment was achieved. Nevertheless, by performing an NMR study similar to that recently described for the NIPP1:PP1 holoenzyme (9) and consistent with previous studies (14), we were able to show that the PNUTS:PP1 binding domain is within residues 376–433 (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3).

To more precisely determine which residues contact PP1, and to test the potential role of PNUTS residues 434–453 in direct PP1 binding, additional PNUTS constructs were generated. ITC measurements showed that PNUTS376–453 binds tightly to PP1 (PP1α7–330) in a 1-to-1 ratio with a Kd of 8.7 ± 0.8 nM (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Surprisingly for an IDP, PNUTS376–453 was not ideally suited for NMR analysis, despite extensive optimization of conditions, because a significant number of peaks were missing in the 2D [1H,15N] HSQC spectrum, likely due to solvent or conformational exchange. Nevertheless, we achieved a ∼82% complete sequence-specific backbone assignment of PNUTS376–453 (Fig. 1A), which allowed us to determine that only residues C-terminal to 394 bind PP1. ITC measurements with two shorter PNUTS constructs showed that PNUTS394–453 and PNUTS394–433 interact with PP1 (PP1α7–330) in a 1-to-1 ratio with similar Kd values (9.8 ± 3.5 nM for PNUTS394–453; 9.3 ± 1.9 nM for PNUTS394–433; Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4), demonstrating that PNUTS residues 394–433 are necessary and sufficient for PP1 binding; NMR studies of the PNUTS376–453:PP1α7–330 complex also show that the PNUTS residues become structured when bound to PP1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Finally, ITC measurements between PNUTS394–433 and PP1β6–327 (10.7 ± 2.6 nM) or PP1γ7–323 (8.8 ± 0.3 nM; PP1γ1) show that PNUTS binds to all three ubiquitously expressed isoforms of PP1 with equal affinities, demonstrating that in vitro, there is likely no differential regulation of PP1 isoforms by PNUTS (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Together, these results show that PNUTS interacts with PP1α, PP1β, and PP1γ very strongly, with Kd values similar to that observed between PP1α and spinophilin (Kd, 8.7 nM) (22) and 10-fold lower (stronger binding) than that observed between PP1α and NIPP1 (Kd, 104 nM) (9).

Fig. 1.

Identification of the minimal PNUTS PP1 binding domain. (A) Two-dimensional [1H, 15N] HSQC spectrum of PNUTS376–453. (B) Isothermal titration calorimetry of PNUTS394–433 and PP1α7–330, confirming that the intrinsically unstructured PNUTS PP1 binding domain is functional and interacts strongly with PP1. (C) PNUTS (orange cartoon) and PP1α (7-300; gray surface) complex. Two Mn2+ ions (magenta spheres) are bound at the PP1 active site; no electron density was observed for PNUTS residues 425–433. (D) The structure of the PNUTS PP1 binding domain with the three primary interaction sites indicated. Residues that make key interactions with PP1 are shown as sticks. (E) Sequence conservation of the PNUTS PP1 binding domain. Position weight matrix for aligned sequences identified using JackHMMER. Blue, positively charged residues; red, negatively charged residues; black, hydrophobic residues; gray, rest. Shaded regions indicate residues that bind in the RVxF (light blue), ΦΦ (beige), and Arg pockets (green).

Crystal Structure of the PNUTS:PP1 Holoenzyme.

To determine how PNUTS binds PP1 at atomic resolution, we determined the 3D structure of the PNUTS394–433:PP1α7–300 holoenzyme (hereafter referred to as PNUTS:PP1; PNUTS394–433 binds PP1α7–330 and PP1α7–300 with similar affinities demonstrating that the C-terminal 30 residues of PP1 do not contribute to binding; SI Appendix, Fig. S4) by molecular replacement using PP1 (PDB ID code 3E7A) as a search model. Crystals were obtained in two space groups, P3221 (1 molecule per asymmetric unit) and P41212 (2 molecules per asymmetric unit). Because the complexes are essentially identical, the PNUTS:PP1 complex from the P3221 crystals is described here (SI Appendix, Table S1).

The structure of the PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme shows that PNUTS residues 396-424 become ordered when bound to PP1 (Fig. 1C). They bind in a largely extended manner at three distinct sites at the top and side of PP1: the RVxF motif (site 1), the ΦΦ motif (site 2), and the newly defined Arg motif (site 3; Fig. 1 D and E). As previously observed, the overall structure of PP1 is largely similar to other reported PP1 structures (5). The interaction between PP1 and PNUTS is extensive, with the complex burying ≥3,300 Å2 of solvent accessible surface area. Two Mn2+ ions are bound at the PP1 active site, which is more than 10 Å away from any residue of PNUTS. Thus, the PP1 catalytic site is accessible in the PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme and fully capable of dephosphorylating model substrates, such as p-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

PNUTS Residue Leu407 Extends the RVxF Binding Pocket.

PNUTS residues 397KTVTW401 constitute the canonical RVxF motif (site 1), which binds PP1 in the RVxF binding pocket. The interactions are similar to those observed in other PP1 holoenzyme complexes, with Val399PNUTS and Trp401PNUTS binding into a deep hydrophobic pocket comprised of PP1 residues Ile169, Leu243, Phe257, Arg261, Val264, Leu266, Met283, Leu289, Cys291, and Phe293 (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). As observed for other PP1 regulators, the “V” and “F” residues of the RVxF motif (Val399PNUTS and Trp401PNUTS) are critical for binding, because mutating these residues to alanine abolishes the ability of PNUTS to bind PP1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

The structure reveals that Leu407PNUTS also contributes to the RVxF binding pocket by forming the “lid” over the bound “F” (Trp401PNUTS) residue. This lid is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions with Tyr255PP1, Phe257PP1, Phe293PP1, and Pro402PNUTS and electrostatic/hydrogen bonding interactions between Arg261PP1 and Glu404PNUTS as well as Tyr255PP1 and Arg408PNUTS. Consistent with this hypothesis, Leu407PNUTS is the residue that becomes most buried in the PNUTS:PP1 complex, even more than the canonical “F” residue of the RVxF motif (Trp401PNUTS). The importance of this residue is further demonstrated by sequence conservation of the PNUTS PP1 binding domain, which shows that Leu407PNUTS, like Trp401PNUTS, is nearly perfectly conserved from humans to the simplest multicellular organisms, i.e., Trichoplax adhearens (Fig. 1E). Finally, comparison with the structures of other PP1 holoenzymes shows that this pocket is regularly occupied by a hydrophobic residue from the PP1 regulatory protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 C and D). Specifically, myosin phosphatase-targeting subunit 1 (MYPT1) residue Ala42 (8), inhibitor-2 (I-2) residue Ile53 (7) and spinophilin residue Leu437 (26) occupy the same PP1 pocket. However, although these residues are structurally conserved, they are not conserved either in sequence or location/distance from the RVxF motif (SI Appendix, Fig. S7E). In PNUTS, MYPT1, and I-2, this residue is C-terminal to the “F” residue of the RVxF motif, but the numbers of intervening amino acids differs for each regulatory protein (5 in PNUTS, 3 in MYPT1, and 4 in I-2). In spinophilin, this residue is 12 amino acids N-terminal to the ‘F’ residue. Thus, PP1 regulatory proteins use distinct structural mechanisms to occupy this site, which we have named ΦR to indicate its role in the RVxF binding pocket. Finally, some PP1 regulatory proteins that use the RVxF site do not interact at the ΦR pocket, as it is not occupied in the NIPP1:PP1 holoenzyme (9).

The ΦΦ Motif Docking Groove Is Malleable.

Comparison of the NIPP1:PP1 and spinophilin:PP1 holoenzyme structures revealed the presence of a recently described, conserved PP1 interaction motif, the ΦΦ motif (5, 9, 22). This motif is characterized by two sequential hydrophobic residues that bind a hydrophobic pocket in PP1, now known as the ΦΦ motif binding pocket (defined by PP1 residues Arg74, Leu75, Tyr78, Met282, Ile295, Leu296, and Lys297). This site is unique because Tyr78PP1 has been shown to alter its rotomer conformation in order to bind distinct regulatory proteins (9).

The structure of the PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme shows that PNUTS also contains a ΦΦ motif, defined by Tyr410PNUTS and Phe411PNUTS (SI Appendix, Fig. S9; mutating these residues to alanine reduces the ability of PNUTS to bind PP1; SI Appendix, Fig. S8). PNUTS residues 409EYFY412 form a short β-strand that hydrogen bonds with PP1 β-strand β14 to extend one of PP1’s two central β-sheets. Both Tyr410PNUTS and Phe411PNUTS are buried when bound to PP1, with Phe411PNUTS becoming almost totally buried (Phe411PNUTS, 89% loss of solvent accessible surface area, SASA; Tyr410PNUTS, 42% loss of SASA). Comparison of the PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme structures from the two different crystal forms showed that two different orientations of Tyr78PP1 are accommodated by the same holoenzyme (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Namely, the ΦΦ motif docking interactions in the P3221 PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme are similar to those observed in the NIPP1:PP1 holoenzyme (SI Appendix, Fig. S9C), whereas those in the P4221 PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme are similar to the spinophilin:PP1 holoenzyme (SI Appendix, Fig. S9D). These distinct interactions at the ΦB binding pocket are accommodated by a rotation of the Tyr78PP1 sidechain around χ1. Tyr78PP1 has been identified to be one of the most conformationally variable residues in PP1 (5), which likely facilitates its ability to accommodate a diversity of hydrophobic sequences at this pocket (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Figs. S9 E–G and S10).

A Conserved Arg Motif in PP1 Regulators.

The third interaction site (site 3) of PNUTS with PP1 is defined by Phe413PNUTS through Asn424PNUTS and is centered on residue Arg420PNUTS, which binds the PP1 C-terminal groove (Fig. 2A). This interaction also results in the largest changes in the conformation PP1 when the PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme is compared with the high resolution structure of PP1 (1.45 Å; SI Appendix, Fig. S11A). PNUTS binding results in a ∼3.5-Å shift of the PP1 C-terminal strand away from helix αB and the C-terminal groove and a second ∼3.5-Å shift of PP1 loop 21GSRPG25 away from helix αB but in the opposite direction compared with strand β14; the latter movement accommodates a salt bridge formed between Glu419PNUTS and Arg74PP1. Although the position of β14 varies depending on the PP1 regulatory protein bound, this is the first time, to our knowledge, that PP1 loop 21GSRPG25 has been observed to change conformation in response to PP1 regulatory protein or inhibitor binding (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 B and C).

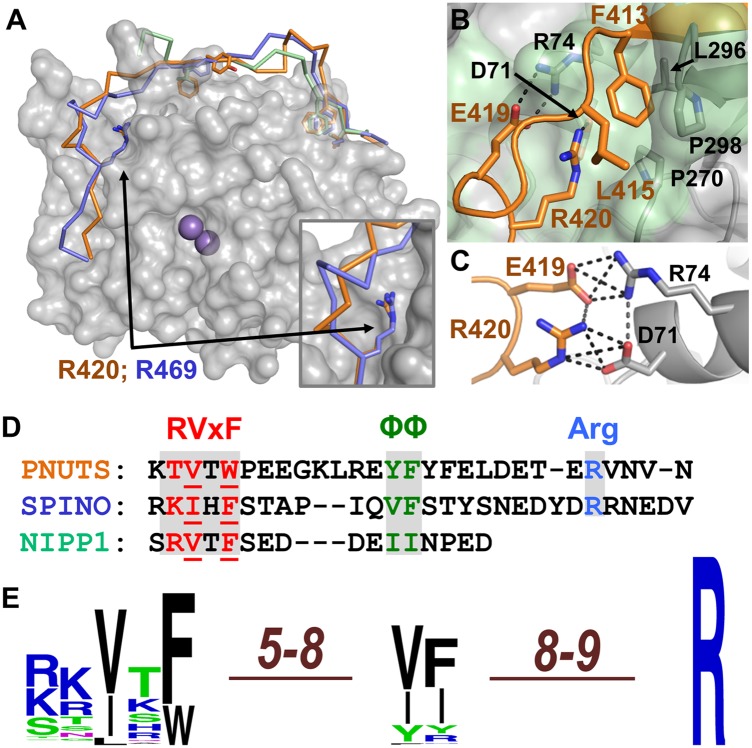

Fig. 2.

Sequence variability in the RVxF, ΦΦ, and Arg motifs. (A) Superposition of the RVxF-ΦΦ-Arg interactions from PNUTS (orange), spinophilin (lavender), and NIPP1 (green) with PP1; PP1 regulatory motif residues, sticks. (Inset) Arg motif binding pockets of PNUTS and spinophilin. (B) Hydrophobic and charged interactions between PNUTS (orange) and PP1 (gray; residues that make up the Arg motif binding pocket are shaded light green). Interacting residues are shown as sticks and labeled. (C) Stacked bidentate salt bridge between Glu419PNUTS and Arg74PP1 and Arg420PNUTS and Asp71PP1. (D) Structure-based sequence alignment of the PNUTS, NIPP1, and spinophilin PP1 interaction domains. (E) Logo illustrating the sequence variability of the RVxF, ΦΦ, and Arg motifs in PNUTS (85 sequences), spinophilin/neurabin (125 sequences), and NIPP1 (107 sequences) orthologs.

The interactions at this site are stabilized by hydrophobic and especially electrostatic contacts. Residues Pro270PP1, Leu296PP1, Pro298PP1, and Leu415PNUTS form a hydrophobic pocket for Phe413PNUTS (Fig. 2B). This site is further stabilized by cation–π interactions between Phe413PNUTS and both Arg74PP1 and Arg420PNUTS. The rest of the interactions are electrostatic. The most significant are those made by Glu419PNUTS and Arg420PNUTS (Fig. 2C), both of which are perfectly conserved among PNUTS sequences (Fig. 1E). Specifically, Glu419PNUTS forms a bidentate salt bridge with Arg74PP1, whereas Arg420PNUTS forms a bidentate salt bridge with Asp71PP1. In free PP1, Arg74PP1 lies across the C-terminal groove and forms an intramolecular salt bridge with Asp71PP1 (5). In contrast, in the presence of PNUTS, the side chain of Arg74PP1 rotates out of the C-terminal groove to interact with Glu419PNUTS. This rotation allows PNUTS to bind in the groove, with Arg420PNUTS “replacing” Arg74PP1 by forming a salt bridge with Asp71PP1. Although Glu419PNUTS and Arg74PP1 are partially exposed to solvent, Asp71PP1 and Arg420PNUTS are both nearly completely buried and, thus, this electrostatic interaction is essential to satisfy the buried charge of both side chains.

Before this work, spinophilin was the only regulator shown to bind PP1 in its C-terminal groove. Comparison of the PNUTS:PP1 and spinophilin:PP1 holoenzyme structures reveals that each of these regulators engages PP1 very differently at this site, with essentially no structural overlap between them (Fig. 2A). The only striking exception is Arg420PNUTS and Arg469SPINO, which overlap perfectly in both complexes (Fig. 2A, Inset). As a consequence, Arg469SPINO, like Arg420PNUTS, forms an identical bidentate salt bridge with Asp71PP1. In addition, like Arg420PNUTS, Arg469SPINO is also perfectly conserved among spinophilin isoforms (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). The discovery that this pocket in PP1 is engaged by two distinct regulators, spinophilin and PNUTS, revealed that this pocket is a conserved docking site for PP1 regulators (common PP1 docking sites are defined as those sites on PP1 that are engaged by at least two distinct PP1 regulators). Because of the striking structural conservation of Arg420PNUTS and Arg469SPINO, and because these residues bind to PP1 via an identical mechanism, we have named this PP1 protein interaction motif the Arg motif.

The Amino Acid Sequence of the ΦΦ Motif, but Not the Arg Motif, Is Diverse.

To date, the structures of six distinct PP1 holoenzymes have been determined [MYPT1:PP1 (8), I-2:PP1 (7), Rb:PP1 (27), spinophilin:PP1/Neurabin:PP1 (22), NIPP1:PP1 (9), and PNUTS:PP1]. Although each of these regulatory proteins includes the canonical RVxF motif, four (MYPT1:PP1, I-2:PP1, spinophilin:PP1/Neurabin:PP1, and PNUTS:PP1) have an extended RVxF motif, three (spinophilin:PP1/Neurabin:PP1, NIPP1:PP1, and PNUTS:PP1) contain the ΦΦ motif, and only two (spinophilin:PP1/Neurabin:PP1 and PNUTS:PP1) contain the Arg motif. However, comparison of these sequences shows that despite the conserved structural interactions, the sequences of the PP1 binding domains of these three regulatory proteins are highly distinct, as are the number of residues between the motifs, making the identification of common binding motifs by sequence alone challenging or even impossible—the single biggest difficulty for understanding PP1 regulation.

Here, we have overcome this problem, as despite these differences, a structure-based sequence alignment (Fig. 2D) allowed us to define two unique, extended PP1 binding motifs: (i) the RVxF-ΦΦ motif RVxF-X5–8-ΦAΦB and (ii) the RVxF-ΦΦ-R motif RVxF-X5–8-ΦAΦB-X8–9-R, where X is any amino acid and Φ represents a hydrophobic amino acid (Fig. 2E). To quantify the sequence variability in this motif, we compared the sequences of PNUTS, NIPP1, and spinophilin/neurabin orthologs present in other organisms using JackHMMER (28). As expected from the structural signatures, the Arg is perfectly conserved (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). In contrast, the ΦΦ sequence is considerably more variable. This variability arises largely from amino acid differences in PNUTS sequences, in which 14 different ΦAΦB combinations are observed among the PNUTS orthologs, whereas only 2 and 5 combinations are observed for NIPP1 and spinophilin/neurabin, respectively (SI Appendix, Table S2). Of the 19 different ΦΦ motifs identified in the NIPP1, spinophilin, and PNUTS sequences, only one, VY, was found in more than one family of PP1 regulators (SI Appendix, Table S2). Thus, although the ΦΦ motif in PNUTS is considerably more diverse than those in NIPP1 and spinophilin, the sequences are distinct from other families of regulators. Finally, although it is clear that at least three, and likely many more, PP1 interacting proteins (see below) bind PP1 via these extended motifs, it is certainly possible that other PP1 regulators engage these binding pockets in a different order.

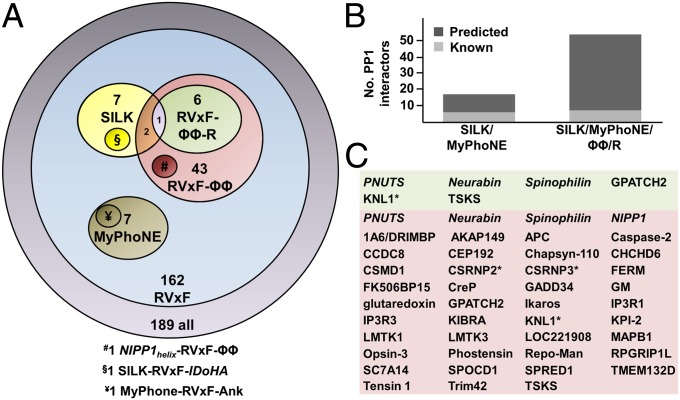

Only a Handful of PP1 Regulators Bind the Arg Motif Binding Pocket.

We then analyzed the confirmed 189 PP1 interacting proteins (4) to identify which PP1 regulators contain one of these two extended motifs. For this analysis, the amino acids at the ΦA and ΦB positions were restricted to those observed in PNUTS, NIPP1, and spinophilin/neurabin sequences (SI Appendix, Table S2), whereas the number of residues between the RVxF and ΦΦ motifs and the ΦΦ and Arg motifs were restricted to those observed experimentally, i.e., 5–8 and 8–9 residues, respectively (this represents the most conservative approach for defining these gaps/sequences and will likely underestimate the number of regulators that bind these sites in a consecutive fashion). This definition identified 52 and 11 PP1 interacting proteins that contain putative RVxF-ΦΦ motifs and RVxF-ΦΦ-R motifs (SI Appendix, Tables S3 and S4), respectively. Because the Arg motif arginine is perfectly conserved while the ΦΦ motif is comparatively degenerate, we further refined the likelihood that the identified proteins contain functional ΦΦ- and Arg motifs by determining: (i) which sequences are predicted to be intrinsically disordered in the absence of PP1 (the PP1 binding domains of spinophilin, neurabin, NIPP1, and PNUTS are both predicted and have also been shown experimentally to be intrinsically disordered in the absence of PP1) and (ii) which sequences have Arg motif arginines that are conserved (the Arg motif binding pocket is deep and charged and is predicted to accommodate only an arginine or, potentially, a lysine). This analysis predicts that 39 of the 52 and 3 of the 11 proteins contain functional RVxF-ΦΦ and/or RVxF-ΦΦ-R motifs, respectively. Taken together, a total of 43 PP1 interacting proteins contain a functional RVxF-ΦΦ motif (39 predicted; 4 whose holoenzyme structures are known) and 6 contain a functional RVxF-ΦΦ-R motif (3 predicted; 3 whose holoenzyme structures are known) (Fig. 3A). This analysis translates into a >20% increase (39 of the 189 confirmed interactors) in the number of PP1 interacting proteins whose mode of interaction with PP1 can now be predicted from sequence alone (Fig. 3B). Although a small subset of these proteins may interact differently with PP1 (i.e., false positives), we predict that most, if not all, will bind PP1 in a manner similar to PNUTS, spinophilin, or NIPP1 (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Tables S3 and S4). Finally, these predictions do not exclude the possibility that other PP1 interaction proteins engage these sites in a different order. Namely, although 43 PP1 interactors were either predicted or experimentally confirmed to contain an RVxF-ΦΦ or RVxF-ΦΦ-R motif, this analysis still leaves well over 100 PP1 interacting proteins to engage PP1 via different combinations of both known and as yet to be discovered binding sites.

Fig. 3.

Key elements underlying the PP1 regulatory code. (A) PP1 regulators with known/predicted PP1 interaction motifs. Of the 189 known PP1 regulators (lavender), 162 have confirmed RVxF interaction motifs (blue). Of these, 43 are predicted/known to contain a functional RVxF-ΦΦ motif, (red; 4 are confirmed: PNUTS, spinophilin, neurabin, NIPP1), with 6 predicted/known to contain a functional RVxF-ΦΦ-R motif (green, 3 confirmed: PNUTS, spinophilin, neurabin). Two other sequence motifs identified in PP1 regulators are the MyPhoNE (R-x-[Q/E]-Q-[ILV]-[RK]-x-W) and the SILK motif ([G/S]-ILK). One PP1 regulator, KNL1, is predicted to contain both a SILK and an RVxF-ΦΦ-R motif (purple), whereas two others, CSRNP2 and CSRNP3, are predicted to contain both a SILK and an RVxF-ΦΦ motif (orange). Additional PP1 interaction elements present in PP1 regulators that are not defined by a sequence motif are the NIPP1helix, the I-2helix, and the MYPT1ankyrin domain. (B) PP1 interaction proteins whose PP1 holoenzyme structures are either known (light gray) or can be predicted based on the presence of either the SILK and MyPhoNE motifs (Left) or the SILK, MyPhoNE, RVxF-ΦΦ, and RVxF-ΦΦ-R motifs (Right). (C) PP1 interactor proteins either known (italics) or predicted to contain a functional RVxF-ΦΦ or RVxF-ΦΦ-R motif; proteins that also contain SILK motifs are indicated by an asterisk.

Discussion

PNUTS was originally identified as a nuclear targeting subunit that functions as a PP1 inhibitor when using the generic PP1 substrate phosphorylase a (a specific substrate of the GM:PP1 holoenzyme) (10). Here, we show that PP1 is active, as the PP1 active site is fully accessible when bound to PNUTS and the PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme is fully capable of hydrolyzing a small molecule mimic of phosphorylated residues, pNPP. So how does PNUTS inhibit phosphorylase a dephosphorylation? Previous studies showed that access to Asp71PP1 is required by phosphorylase a for effective dephosphorylation (22, 29). Thus, PNUTS, like spinophilin, inhibits PP1 activity through a model of “steric inhibition”; that is, PNUTS sterically blocks phosphorylase a from engaging PP1 in the C-terminal groove, preventing its dephosphorylation by PP1. Consistent with this mechanism, previous studies showed that PNUTS fragment 392–415, which does not contain the Arg motif residue, Arg420PNUTS, does not inhibit phosphorylase a dephosphorylation (14). Thus, PNUTS actively directs PP1 substrate specificity by blocking a subset of substrates—i.e., those requiring access to the PP1 C-terminal groove, including phosphorylase a—from binding PP1. This mechanism of altered substrate dephosphorylation by steric occlusion of substrate binding sites is becoming a hallmark regulatory mechanism of the entire PSP family (22, 30), as it was recently shown that a protein inhibitor, A238L, and also the immunosuppressants FK506 and cyclosporin A, inhibit calcineurin function by using a similar mechanism (30).

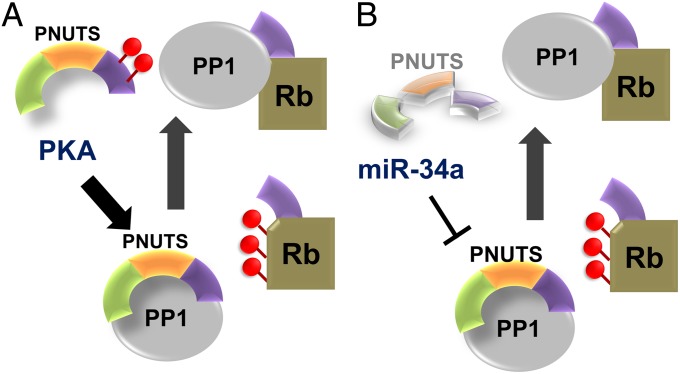

PNUTS is also important because it antagonizes Rb dephosphorylation, making the PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme a cancer drug target. Using a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments, Rb was shown to have an RVxF motif that is strictly required for its dephosphorylation by PP1 (27). Thus, Rb, which binds PP1 weakly (Kd, 3,900 nM), competes with RVxF-containing PP1 regulators for PP1 binding. Because, PNUTS binds PP1 ∼400-fold more strongly (Kd, 9.3 nM) in the presence of PNUTS, Rb is excluded from the RVxF site and cannot be effectively dephosphorylated (Fig. 4). So how is Rb dephosphorylated? PNUTS has been shown to be phosphorylated by PKA at two threonine residues close to the RVxF motif, which substantially reduces PNUTS:PP1 complex formation (14) (Fig. 4A). In addition, PNUTS was also recently shown to be a target of microRNA miR-34a (17). Namely, up-regulation of miR-34a leads to a potent reduction in PNUTS expression, which, like PKA phosphorylation, reduces the amount of PNUTS:PP1 holoenzyme in the nucleus (Fig. 4B). Both regulatory mechanisms increase the amount of Rb binding-competent PP1 available to dephosphorylate and activate Rb. Based on these observations, we predict that PNUTS inhibits the dephosphorylation of Ser15 on p53 and Ser395 on MDM2 by using a similar mechanism (19). Namely, that PNUTS binds PP1 at an interaction surface required by either the substrates (p53 and/or MDM2) or the PP1 regulatory proteins that target them to PP1 for dephosphorylation (i.e., iASPP, which was recently shown to form a ternary complex between p53 and PP1 (31); it is unknown whether iASPP and PNUTS, both of which contain an RVxF motif, can bind PP1 simultaneously to allow for the formation of a tetrameric complex with p53). Thus, PNUTS appears to function as both a targeting protein that enhances the dephosphorylation of a set of as yet largely unknown PP1 substrates (the only potential substrate identified for the PP1:PNUTS holoenzyme is the C-terminal domain of RNAPII; refs. 20 and 21) but also, and perhaps more significantly, a protein that antagonizes the PP1-mediated dephosphorylation of another separate set of PP1 substrates, i.e., that of Rb, p53, and MDM2.

Fig. 4.

Regulation of Rb activity by PNUTS. (A) PKA phosphorylation of two residues close to the PNUTS RVxF motif reduces the affinity of PNUTS for PP1, freeing PP1 to bind and dephosphorylate Rb. (B) MicroRNA miR-34a suppresses the expression of PNUTS, increasing the PP1 available to bind and dephosphorylate Rb.

PNUTS:PP1 and NIPP1:PP1 constitute a significant fraction of the total PP1 in the nucleus (32). Because both holoenzyme structures are known, these complexes provide an opportunity to understand how distinct holoenzymes in the same cellular location differentially direct PP1 specificity. Our data shows that although both targeting proteins bind the RVxF and ΦΦ motif binding pockets, they also make distinct interactions with PP1: i.e., PNUTS binds the C-terminal groove via its Arg motif, whereas NIPP1 binds the bottom of PP1 below its hydrophobic groove via the NIPP1helix (9). As a consequence, they differentially direct PP1 substrate specificity (9, 33). Although NIPP1, like PNUTS, contains an RVxF motif, the affinity of NIPP1 for PP1 is 10-fold lower than that of PNUTS, explaining why PNUTS appears to be a more potent inhibitor of Rb dephosphorylation (18, 34, 35).

Finally, this study also led to the definition of two extended RVxF motifs, the RVxF-ΦΦ and the RVxF-ΦΦ-R motifs. This analysis allowed us to identify, based on primary sequence, which biochemically confirmed PP1 regulators are likely to contain these functional motifs and, in turn, how they bind and direct the specificity of PP1. To date, no substrates have been identified that use the ΦΦ motif binding pocket to engage PP1, making (thus far) the ΦΦ a purely structural motif. In contrast, both the RVxF and Arg motif binding pockets are used by substrates, such as Rb (RVxF) and phosphorylase a (Arg). Thus, these motifs act as both structural and functional motifs, enhancing PP1 targeting protein binding while also blocking the ability of a subset of substrates to bind PP1. Together, our data not only provide the molecular basis by which PNUTS directs PP1 substrate specificity in the nucleus but also allows us to predict how a significant subset of PP1 targeting proteins bind and regulate PP1 activity.

Materials and Methods

Detailed methods are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. The experimental procedures for the expression and purification of all proteins and PP1 holoenzymes, NMR measurements, and ITC are described. The methods for pull-down assays, crystallization and structure determination for free-PP1 and the PNUTS:PP1 complexes, and bioinformatics analysis are also described.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. B. Dancheck and Ms. J. Meissner for assistance and Dr. M. Allaire and Dr. A. Soares for beamline support. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)-National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Grant R01GM098482 (to R.P.). M.S.C. was partially supported by National Medical Research Council of Singapore Individual Research Grant NMRC/GMS/1252/2010 awarded to Dr. S. Shenolikar (Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore). Data for this study were measured at beamline X25 of the National Synchrotron Light Source. Financial support comes principally from the Offices of Biological and Environmental Research and of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy, and from National Center for Research Resources Grant P41RR012408 and NIGMS Grant P41GM103473 of the NIH. This research is based in part on data obtained at the Brown University Structural Biology Core Facility, which is supported by the Division of Biology and Medicine, Brown University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.M.V. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: The NMR chemical shifts have been deposited in the BioMagResBank, www.bmrb.wisc.edu (accession no. 19451). The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 4MOV, 4MOY, and 4MP0).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1317395111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Peti W, Nairn AC, Page R. Folding of intrinsically disordered protein phosphatase 1 regulatory proteins. Curr Phys Chem. 2012;2(1):107–114. doi: 10.2174/1877946811202010107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bollen M, Peti W, Ragusa MJ, Beullens M. The extended PP1 toolkit: Designed to create specificity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(8):450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choy MS, Page R, Peti W. Regulation of protein phosphatase 1 by intrinsically disordered proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40(5):969–974. doi: 10.1042/BST20120094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heroes E, et al. The PP1 binding code: A molecular-lego strategy that governs specificity. FEBS J. 2013;280(2):584–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peti W, Nairn AC, Page R. Structural basis for protein phosphatase 1 regulation and specificity. FEBS J. 2013;280(2):596–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egloff M-P, et al. Structural basis for the recognition of regulatory subunits by the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 1. EMBO J. 1997;16(8):1876–1887. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurley TD, et al. Structural basis for regulation of protein phosphatase 1 by inhibitor-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(39):28874–28883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terrak M, Kerff F, Langsetmo K, Tao T, Dominguez R. Structural basis of protein phosphatase 1 regulation. Nature. 2004;429(6993):780–784. doi: 10.1038/nature02582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connell N, et al. The molecular basis for substrate specificity of the nuclear NIPP1:PP1 holoenzyme. Structure. 2012;20(10):1746–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen PB, Kwon YG, Nairn AC, Greengard P. Isolation and characterization of PNUTS, a putative protein phosphatase 1 nuclear targeting subunit. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(7):4089–4095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kreivi JP, et al. Purification and characterisation of p99, a nuclear modulator of protein phosphatase 1 activity. FEBS Lett. 1997;420(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01485-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Totaro A, et al. Cloning of a new gene (FB19) within HLA class I region. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250(3):555–557. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raha-Chowdhury R, Andrews SR, Gruen JR. CAT 53: A protein phosphatase 1 nuclear targeting subunit encoded in the MHC Class I region strongly expressed in regions of the brain involved in memory, learning, and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;138(1):70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YM, et al. PNUTS, a protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) nuclear targeting subunit. Characterization of its PP1- and RNA-binding domains and regulation by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(16):13819–13828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landsverk HB, Kirkhus M, Bollen M, Küntziger T, Collas P. PNUTS enhances in vitro chromosome decondensation in a PP1-dependent manner. Biochem J. 2005;390(Pt 3):709–717. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landsverk HB, et al. The protein phosphatase 1 regulator PNUTS is a new component of the DNA damage response. EMBO Rep. 2010;11(11):868–875. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boon RA, et al. MicroRNA-34a regulates cardiac ageing and function. Nature. 2013;495(7439):107–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Leon G, Sherry TC, Krucher NA. Reduced expression of PNUTS leads to activation of Rb-phosphatase and caspase-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7(6):833–841. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.6.5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SJ, et al. Protein phosphatase 1 nuclear targeting subunit is a hypoxia inducible gene: Its role in post-translational modification of p53 and MDM2. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14(6):1106–1116. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciurciu A, et al. PNUTS/PP1 regulates RNAPII-mediated gene expression and is necessary for developmental growth. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(10):e1003885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jerebtsova M, et al. Mass spectrometry and biochemical analysis of RNA polymerase II: Targeting by protein phosphatase-1. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;347(1-2):79–87. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0614-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ragusa MJ, et al. Spinophilin directs protein phosphatase 1 specificity by blocking substrate binding sites. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(4):459–464. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dancheck B, Nairn AC, Peti W. Detailed structural characterization of unbound protein phosphatase 1 inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2008;47(47):12346–12356. doi: 10.1021/bi801308y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsh JA, et al. Structural diversity in free and bound states of intrinsically disordered protein phosphatase 1 regulators. Structure. 2010;18(9):1094–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinheiro AS, Marsh JA, Forman-Kay JD, Peti W. Structural signature of the MYPT1-PP1 interaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(1):73–80. doi: 10.1021/ja107810r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ragusa MJ, Allaire M, Nairn AC, Page R, Peti W. Flexibility in the PP1:spinophilin holoenzyme. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(1):36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirschi A, et al. An overlapping kinase and phosphatase docking site regulates activity of the retinoblastoma protein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(9):1051–1057. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR. HMMER web server: Interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Web Server issue):W29–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Zhang Z, Brew K, Lee EY. Mutational analysis of the catalytic subunit of muscle protein phosphatase-1. Biochemistry. 1996;35(20):6276–6282. doi: 10.1021/bi952954l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grigoriu S, et al. The molecular mechanism of substrate engagement and immunosuppressant inhibition of calcineurin. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(2):e1001492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skene-Arnold TD, et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction of protein phosphatase-1c with ASPP proteins. Biochem J. 2013;449(3):649–659. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jagiello I, Beullens M, Stalmans W, Bollen M. Subunit structure and regulation of protein phosphatase-1 in rat liver nuclei. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(29):17257–17263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minnebo N, et al. NIPP1 maintains EZH2 phosphorylation and promoter occupancy at proliferation-related target genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(2):842–854. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graña X. Downregulation of the phosphatase nuclear targeting subunit (PNUTS) triggers pRB dephosphorylation and apoptosis in pRB positive tumor cell lines. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7(6):842–844. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.6.6298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Udho E, Tedesco VC, Zygmunt A, Krucher NA. PNUTS (phosphatase nuclear targeting subunit) inhibits retinoblastoma-directed PP1 activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297(3):463–467. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.