Significance

Although mixed social environments can provoke conflict, where this diversity promotes positive intergroup contact, prejudice is reduced. Seven multilevel studies demonstrate that the benefits of intergroup contact are broader than previously thought. Contact not only changes attitudes for individuals experiencing direct positive intergroup contact, their attitudes are also influenced by the behavior (and norms) of fellow ingroup members in their social context. Even individuals experiencing no direct, face-to-face intergroup contact can benefit from living in mixed settings where fellow ingroup members do engage in such contact. Two longitudinal studies rule out selection bias as an explanation for these findings on the contextual level. Prejudice is a function not only of whom you interact with, but also of where you live.

Keywords: diversity, trust, social norms, multilevel analysis

Abstract

We assessed evidence for a contextual effect of positive intergroup contact, whereby the effect of intergroup contact between social contexts (the between-level effect) on outgroup prejudice is greater than the effect of individual-level contact within contexts (the within-level effect). Across seven large-scale surveys (five cross-sectional and two longitudinal), using multilevel analyses, we found a reliable contextual effect. This effect was found in multiple countries, operationalizing context at multiple levels (regions, districts, and neighborhoods), and with and without controlling for a range of demographic and context variables. In four studies (three cross-sectional and one longitudinal) we showed that the association between context-level contact and prejudice was largely mediated by more tolerant norms. In social contexts where positive contact with outgroups was more commonplace, norms supported such positive interactions between members of different groups. Thus, positive contact reduces prejudice on a macrolevel, whereby people are influenced by the behavior of others in their social context, not merely on a microscale, via individuals’ direct experience of positive contact with outgroup members. These findings reinforce the view that contact has a significant role to play in prejudice reduction, and has great policy potential as a means to improve intergroup relations, because it can simultaneously impact large numbers of people.

The world is becoming increasingly diverse, fueling debate about relations between, especially, ethnic and religious groups (1, 2). Earlier attempts to explain majority group members’ prejudice toward minority outgroups proposed that social environments characterized by greater proportions of (minority) outgroup members inevitably invoke perceptions of competitive threat to the (majority) ingroup’s position, provoking intergroup tension (3), and there is evidence that as minority group proportion increases, so does prejudice and threat (4–6). However, such analyses fail to include the role of intergroup contact (7). Positive intergroup contact provides a way to overcome intergroup tensions and conflict that are often associated with segregation (8), and extensive evidence shows that positive face-to-face contact, especially between cross-group friends (9), reduces outgroup prejudice among minority and especially majority group members (10). Many of these studies have used prejudice as the dependent variable, but outcome measures have also included threat, trust, and outgroup bias; we use the term “prejudice” loosely to include all these measures assessing the climate of intergroup relations. The impact of contact is, however, not limited to the effect of such direct contact. Extended contact, knowing that another ingroup member has positive outgroup contact, can also reduce outgroup prejudice (11). Almost all prior research on intergroup contact effects is, however, limited by its focus on the impact of individual, microlevel contact on prejudice. Could prejudice be a function of not only whom you know, but also where you live? If so, then this finding would elevate contact theory to a theoretical approach with macrolevel implications, and consequent policy implications for improving intergroup relations.

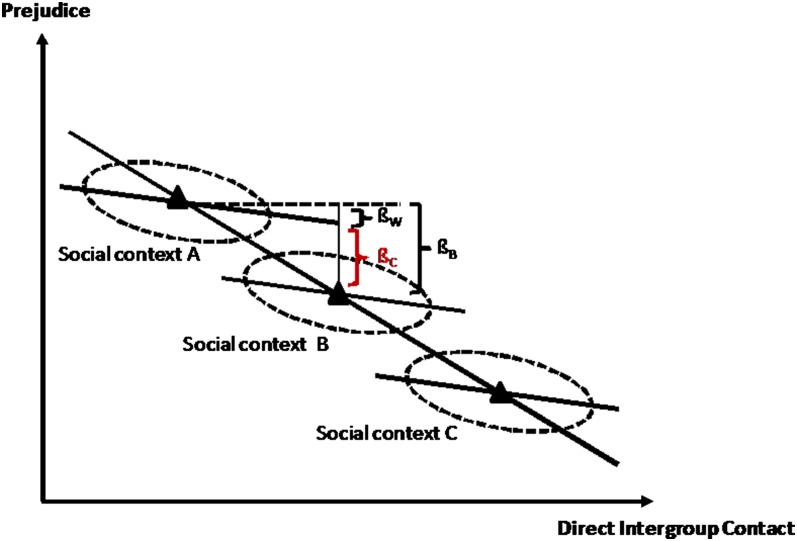

Though some studies have shown that for social contexts, like regions or districts, a higher context level of intergroup contact is associated with less prejudice (12), these studies did not test the contextual effect of contact (3), the difference between the effect of intergroup contact between social contexts (the between-level effect), and the effect of individual-level contact within contexts (the within-level effect) (13) on prejudice. Evidence for this contextual effect of positive contact would indicate that living in a place in which other ingroup members interact positively with members of the outgroup should reduce prejudice, beyond one’s own contact experiences and irrespective of whether one knows the ingroup members experiencing intergroup contact. Thus, a person living in a context with a higher mean level of positive intergroup contact is likely to be less prejudiced than a person with the same level of direct positive contact, but living in a context with a lower mean level of intergroup contact (Fig. 1). Evidence, especially longitudinal data, for this contextual effect of contact would demonstrate that intergroup contact at the social context level has greatest consequences for individuals’ attitudes (and behaviors), and that the processes involved cannot be reduced to characteristics of individuals or specific situations in which intergroup contact occurs (14), or selection bias. This evidence would make a theoretical contribution in better understanding the consequences of diversity, and a practical contribution in underlining the policy potential of contact as a social intervention to improve intergroup relations on a wider level (15, 16).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the proposed contextual effect of intergroup contact. ▲, mean level of intergroup contact within social context (group mean of intergroup contact); βW, mean effect of intergroup contact within social contexts (within-level effect of intergroup contact); βB, effect of intergroup contact between social contexts (between-level effect of intergroup contact); βC, contextual effect of intergroup contact (difference between the between-level and within-level effect of intergroup contact).

We propose that perceived ingroup norms in social contexts where positive contact with outgroups is more commonplace are more tolerant, supporting positive interactions with outgroup members (17). These norms, based on perceptions of what ingroup members think, prescribe appropriate attitudes, values, and behaviors toward outgroup members, and prejudice is dependent on norms that support or oppose these prejudices (18). Moreover, norms influence people’s attitudes toward, and willingness to interact with, outgroup members (8, 19). In four of our seven studies, we tested whether living in a social context in which individuals have, on average, more positive contact is associated with more tolerant social norms within these contexts. If so, this should lead to more tolerant outgroup attitudes, over and above the effect of individual contact experiences. To approximate norms at the neighborhood level, we measured diversity beliefs, which reflect the extent to which individuals value and endorse diversity (20–22). This construct was expressly developed to capture the belief that high diversity is instrumental to accomplishing the ingroup’s goals (20); it is a construct that is theoretically and statistically related to, but distinct from, outgroup prejudice (when both were measured at the individual level; see SI Text, footnote) (23). When estimated at the social context level, for example, the neighborhood level (i.e., as a random effect, involving the average or aggregate level of diversity beliefs in the neighborhood), our measures of diversity beliefs reflect positive social norms in the neighborhood.

Studies 1a to 1e

We first sought evidence for the contextual effect of contact in five large cross-sectional survey data sets from a range of intergroup contexts, varying in the narrowness of the social context indicator (SI Text). The data for study 1a were taken from the European Social Survey (24), with context measured at the regional level. Study 1b used a 2002 probability survey of the German adult population, with context measured at the district level. Study 1c relied on data from a 2005 national survey of White Americans with context measured at the census tract level. Study 1d used survey data from White British respondents in a 2009–2010 national survey in England, with context measured at the neighborhood level.* Study 1e tested the contextual effect among minority respondents (in the sense of historically disadvantaged groups) in a 2011 city survey in Cape Town, South Africa, with context measured at the neighborhood level. All five data sets measured contact (cross-group friendships) and outgroup prejudice. Studies 1a, 1d, and 1e included indicators for social norms (for item wording, see SI Text). All studies included a range of pertinent individual (education) controls, and three studies (1b–1d) also included context-level (e.g., regional GDP) controls (for details, see SI Text). We used all available controls, but only had contextual-level measures of deprivation in specific studies (SI Text).

To assess the contextual effect of intergroup contact, we used multilevel modeling with the multilevel latent covariate approach (25) (for details, see SI Text). Respondents (within-level) were nested within contexts (between-level; e.g., neighborhoods). A contextual effect is indicated when the between-level effect of intergroup contact (βB in Fig. 1) is significantly larger than the within-level effect (βW in Fig. 1). We assessed the magnitude of the contextual effect by calculating an effect size measure (ES2; see SI Text) (26).

Results are summarized in Table 1. In all analyses, both at the individual level as well as at the social context level, intergroup contact was significantly negatively related to prejudice. As predicted, in all analyses the between-level effect of intergroup contact on prejudice was significantly larger than the within-level effect, yielding a relatively small effect size of the contextual effect of contact (ES2 ranged from 0.21 to 0.35). In study 1e, which used respondents from two groups (Black and so-called “Colored” in Cape Town, South Africa), we found a significant contextual effect, providing preliminary evidence for a contextual effect among disadvantaged (or minority) groups as well.

Table 1.

Unstandardized estimates (SE in brackets) for the contextual effect (studies 1a–1e) and the contextual effect controlling for norms (studies 1a, 1d, and 1e)

| Study 1a† | Study 1b | Study 1c | Study 1d | Study 1e‡ | ||||||

| β (SE) | P | β (SE) | P | β (SE) | P | β (SE) | P | β (SE) | P | |

| Within-level effect | −0.189 (0.009) | <0.001 | −0.351 (0.023) | <0.001 | −0.082 (0.039) | 0.035 | −0.555 (0.101) | <0.001 | −0.21 (0.05) | <0.001 |

| Between-level effect | −0.738 (0.099) | <0.001 | −0.663 (0.062) | <0.001 | −0.416 (0.162) | 0.010 | −1.465 (0.342) | <0.001 | −0.47 (0.12) | <0.001 |

| Contextual effect | −0.549 (0.101) | <0.001 | −0.311 (0.073) | <0.001 | −0.334 (0.177) | 0.059 | −0.910 (0.377) | 0.016 | −0.25 (0.14) | <0.001 |

| Effect size of contextual effect | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.21 | |||||

| Contextual effect without controls | −0.495 (0.102) | <0.001 | −0.282 (0.069) | <0.001 | −0.270 (0.166) | 0.104 | −0.929 (0.379) | 0.014 | −0.226 (0.131) | 0.085 |

| Contextual effect controlling for norms | −0.135 (0.084) | 0.106 | 0.33 (0.37) | 0.37 | 0.42 (0.27) | 0.542 | ||||

| Indirect effect of context§ | −0.418 (0.097) | <0.001 | −1.39 (0.44) | 0.002 | −0.71 (0.23) | 0.010 | ||||

All estimates are controlled for between-country differences in variables.

The contextual effect for all groups is reported; due to sample sizes, further differentiation by ethnic group was not possible.

The indirect effect reflects the effect of contact on prejudice via norms (assessed as diversity beliefs) on the social context level, and indicates whether the contextual effect is significantly reduced after controlling for norms on the social context level.

Next, we tested whether the contextual effect could be explained by differences in social norms between the different social contexts in studies 1a, 1d, and 1e. We reestimated the contextual effect after including norms as an additional predictor of prejudice on the between-level (including norms as a predictor on the within-level, too), thus controlling for between-context differences in ingroup norms. To test whether there was a significant reduction in the contextual effect when controlling for social norms, we tested the indirect effect of intergroup contact on prejudice via social norms on the between-level effect using multilevel mediational analysis (27). A significant indirect effect provides evidence for a reduction in the contextual effect of intergroup contact when controlling for social norms.

When norms were controlled, the difference between the within-level and the between-level effect of intergroup contact was substantially reduced in all cases (see significant indirect effects in Table 1). The contextual effect was rendered nonsignificant in all tests when between-context differences in norms were statistically controlled. Thus, living in a place where fellow ingroup members interact positively with outgroup members has a benign impact on prejudice, beyond one’s own contact experiences, via social norms that value diversity (11).

Studies 2a and 2b

A possible interpretation of the study 1 results is that people who are low in prejudice are more likely to select places to live that are more diverse. Although this interpretation contradicts evidence that prejudice rises with minority group proportions (3–6), it remains possible that more tolerant people select places with higher context-level contact. We sought to rule out this self-selection account by testing the contextual effect in two studies using longitudinal data (studies 2a and 2b), with controls, enabling us to compare the relation of intergroup contact with prejudice over time on the individual and social context levels (Fig. 1). Moreover, detecting a contextual effect of contact using longitudinal data would constitute a stronger case for the effect, compared with cross-sectional data, because we can demonstrate that contact at time 1 is associated with reduced prejudice at time 2, thus overcoming the so-called “causal sequence problem.” In study 2a, only indicators for intergroup contact and prejudice were available, whereas study 2b also measured social norms (for item wording, see SI Text). Data for study 2a were drawn from respondents with no migration background, who participated in two waves (time 1, 2002; time 2, 2006) of a multiwave panel study representative of the German adult population. For study 2b, respondents, randomly sampled from 16 different cities in Germany, were surveyed in 2010 and 2011.

We estimated the contextual effect of intergroup contact over time using a multilevel cross-lagged panel model. We compared the cross-lagged effect of intergroup contact at time 1 on prejudice at time 2 at the social context level (between-level) with the same cross-lagged effect on the individual level (within-level), controlling for the autoregressive effects (associations between the same measures over time; for complete results of autoregressive and cross-lagged effects, see Table 2). For study 2a, the cross-lagged effect of intergroup contact was negative and significant at the between level (β = −0.298, SE = 0.078, P < 0.001), and negative and marginally significant at the within level (β = −0.055, SE = 0.029, P = 0.059). Thus, at both levels, more intergroup contact was associated with less prejudice over time. There was a small contextual effect of intergroup contact over time (ES2 = 0.29): the between-level cross-lagged effect of intergroup contact was significantly larger than the within-level cross-lagged effect (β = −0.243, SE = 0.085, P = 0.004; without controls: β = −0.223, SE = 0.085, P = 0.009). The between-level cross-lagged effect of prejudice on contact was nonsignificant (β = −0.101, SE = 0.206, P = 0.624), ruling out selection bias.

Table 2.

Unstandardized estimates (SE in brackets) for the autoregressive and cross-lagged effects in studies 2a and 2b

| Model | Study 2a | Study 2b | ||

| β (SE) | P | β (SE) | P | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| Level 1 | ||||

| contacttime1 → contacttime2 | 0.583 (0.031) | <0.001 | 0.624 (0.039) | <0.001 |

| prejudicetime1 → prejudicetime2 | 0.611 (0.024) | <0.001 | 0.677 (0.027) | <0.001 |

| contacttime1 → prejudicetime2 | −0.055 (0.029) | 0.059 | −0.002 (0.004) | 0.547 |

| prejudicetime1 → contacttime2 | −0.052 (0.026) | 0.044 | −0.560 (0.187) | 0.003 |

| Level 2 | ||||

| contacttime1 → contacttime2 | 0.910 (0.101) | <0.001 | 0.984 (0.169) | <0.001 |

| prejudicetime1 → prejudicetime2 | 0.439 (0.173) | 0.011 | 0.755 (0.209) | <0.001 |

| contacttime1 → prejudicetime2 | −0.298 (0.078) | <0.001 | −0.039 (0.015) | 0.009 |

| prejudicetime1 → contacttime2 | −0.101 (0.206) | 0.624 | 2.848 (2.107) | 0.177 |

| Contextual effect | −0.243 (0.085) | 0.004 | −0.037 (0.016) | 0.024 |

| Effect size of contextual effect | 0.29 | 0.17 | ||

| Model 2 | ||||

| Level 2 | ||||

| contacttime1 → contacttime2 | 0.989 (0.160) | <0.001 | ||

| prejudicetime1 → prejudicetime2 | 0.467 (0.221) | 0.034 | ||

| contacttime1 → prejudicetime2 | −0.043 (0.015) | 0.006 | ||

| prejudicetime1 → contacttime2 | 4.028 (2.492) | 0.106 | ||

| normstime1 → normstime2 | 0.391 (0.146) | 0.007 | ||

| contacttime1 → normstime 2 | 0.084 (0.030) | 0.005 | ||

| normstime1 → prejudicetime2 | −0.146 (0.057) | 0.011 | ||

| Contextual effect controlling for norms | 0.036 (0.017) | 0.033 | ||

| Indirect effect of context | 0.012 (0.007) | 0.086 | ||

Note. Model 1 considers only the relationships between contact and prejudice; model 2 adds norms as a mediator. For model 2, level 1 results are shown in Table S1.

For study 2b, the cross-lagged effect of intergroup contact was negative and significant at the between level (β = −0.039, SE = 0.015, P = 0.009), and negative, but nonsignificant at the within level (β = −0.002, SE = 0.004, P = 0.547). Only at the between level was more intergroup contact associated with less prejudice over time. The between-level cross-lagged effect of intergroup contact was significantly larger than the within-level cross-lagged effect (β = −0.037, SE = 0.016, P = 0.024; without controls: β = −0.037, SE = 0.016, P = 0.020), demonstrating longitudinally a small contextual effect (ES2 = 0.17) of intergroup contact. Again, the between-level cross-lagged effect of prejudice on contact was nonsignificant (β = 2.848, SE = 2.107, P = 0.177). In study 2b we also tested the mediational effect of social norms longitudinally, which was negative and approached significance (β = −0.012, SE = 0.007, P = 0.086); the contextual effect remained significant (β = −0.036, SE = 0.017, P = 0.033). Although the power in study 2b was low at the social context level (n = 50), the results support the assumption that the contextual effect of intergroup contact can be partly explained by changes in social norms over time. In study 2b, on the within level, the significant longitudinal effect of time 1 prejudice on time 2 contact, together with the absence of a longitudinal effect from contact to prejudice, supports a pattern of self-selection (prejudice leads to contact). We have no ready explanation for this unpredicted result, but selection effects have been found in prior research (28). However, this result does not undermine our longitudinal demonstration of the contextual effect, an effect that cannot be explained with selection bias.

These findings show that the contextual effect cannot be totally explained with self-selection (because in the two longitudinal studies we control for selection). Selection would lead to a causal order from prejudice to norms to contact. We show, longitudinally, the opposite direction at the context level. Although prejudiced people might avoid individual contact, they still profit from the “contextual effect of contact,” i.e., people in general have more intergroup contact in their environment.

One possible alternative explanation of the contextual effect is that individuals high in prejudice avoid social contexts in which people have frequent intergroup contact. Thus, in social contexts with a high mean level of prejudice, the contextual effect should be smaller or even absent. In studies 2a and 2b, we were able to test whether the contextual effect was dependent on the mean prejudice level within the social contexts. We included the interaction between contact and prejudice at time 1, both measured on the between level. In study 2a, the interaction was negative and significant (β = −0.201, SE = 0.084, P = 0.017), whereas in study 2b, the interaction was negative but not significant (β = −0.008, SE = 0.020, P = 0.677). Results for study 2b showed that the contextual effect was not influenced by the mean level of prejudice within a social context. In study 2a, the contextual effect was even stronger in social contexts with a high mean level of prejudice. Together, these results do not support self-selection as a possible alternative explanation of our data on the contextual effect.

Discussion

To conclude, our data show consistently across seven studies that individuals’ outgroup attitudes are more positive when living in social contexts in which people have, on average, more positive intergroup contact. Moreover, we found a consistent contextual effect of contact on prejudice in each study: indeed, the effect of intergroup contact between social contexts is greater than the effect of individual-level contact within contexts. In four studies we provided evidence that this contextual effect is accompanied by more tolerant social norms that possibly explain the larger effect of intergroup contact on the social-context level of analysis. Thus, positive intergroup contact is associated with reduced prejudice on a macro- and not merely microlevel, whereby people are influenced by the behavior of others in their wider social context.

Three key considerations speak to the robustness of our findings. First, results were replicated over seven studies, using a range of measures (of contact, norms, and prejudice), contexts (regions, districts, and neighborhoods), respondents (from both majority and minority groups), and countries. Second, we obtained evidence for the contextual effect both with no statistical controls and with several controls at the individual and context level. Third, we demonstrated the contextual effect in two longitudinal studies. This finding confirms that, over time, the context-level effect of contact is greater than its individual-level effect, and that contact impacts prejudice. In sum, we are confident that our findings are high in generalizability, reliable, and demonstrate an effect from positive contact to reduced prejudice.

We do, however, acknowledge some limitations of our program of research and hence areas for future research. First, the measures of some key constructs in some studies were suboptimal (measured with a single indicator, or as difference scores) because we sought to demonstrate the contextual effect using both archival and our own data from a wide range of contexts; notwithstanding, the effect size of the contextual effect is robust across studies (Tables 1 and 2), so we may well have underestimated the size of the contextual effect. Second, thus far the longitudinal evidence is based exclusively on German data, and these results should be replicated in other contexts. Third, in two of the studies (studies 1a and 1e), context-level controls were not available, although given that we detected contextual effects in four other studies that included such controls, it is unlikely that results reported are solely attributable to some other variable. Finally, in study 1e, we reported a significant contextual effect for lower status groups in Cape Town, South Africa, but due to sample size we were unable to disaggregate results for Coloreds (the numerical majority in this city) and Blacks (both a numerical and social minority), in a society where Whites continue to benefit from the historical advantages of their majority group status. Future research should test the contextual effect on minority groups who have lower status and are in a numerical minority.

These findings have two notable implications. First, macrolevel diversity should not be equated with actual intergroup contact. It is not sufficient to report the proportion of outgroup members in an area; one must report the extent to which members of different groups engage in positive contact. Second, contact has even more beneficial effects than was previously thought (10, 15). Contact does not merely change attitudes on a microscale, in the case of those people who experience direct positive contact with members of the outgroup, nor do interventions on that microlevel offer the only means of reducing prejudice. Rather, contact also affects prejudice on a macrolevel, whereby people are influenced by the behavior of others in their social context. Prior research that has prioritized the interpersonal nature of contact has ignored its potential widespread impact. Even individuals who have no direct intergroup contact experience can benefit from living in mixed settings, provided that fellow ingroup members do engage in positive intergroup contact: Prejudice is a function not only of whom you know, but also of where you live.

These findings demonstrate the policy potential of contact at the context level, because it can be implemented via macrolevel contexts such as mixed schools, neighborhoods, and workplaces. Our research demonstrates the value of living in mixed settings where positive intergroup interaction occurs, over and above positive effects of each individual’s own positive contact experiences. This potential positive impact of diversity, via intergroup contact, is, however, constrained by segregation (29), which precludes contact. The full potential of positive intergroup contact can only be realized with a reduction in segregation that results in increased opportunities for contact, and of course when members of different groups take up those opportunities and engage in more frequent, positive, face-to-face contact.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Research Fellowship CH 743, 2-1 (to O.C.) and a Leverhulme Trust Programme Grant (to M.H.). Data collection was supported by Volkswagen Stiftung and Freudenberg Stiftung (studies 1b and 2a; awarded to Wilhelm Heitmeyer, University of Bielefeld); the Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy (the U.S. Citizenship, Involvement, Democracy Survey used in study 1c, which was commissioned by Georgetown University’s Center for Democracy and Civil Society); the Leverhulme Trust (study 1d); and the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity (studies 1d, 1e, 2b).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*Study 1d included a large sample of various minority groups in the United Kingdom (n = 798; e.g., Blacks, Asians). The ICC for the prejudice measure was small (0.02), resulting in a nonconvergence of our analysis, so we could not test the contextual effect for minority group members.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1320901111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hooghe M, Reeskens T, Stolle D, Trappers A. Ethnic diversity and generalized trust in Europe: A cross-national multilevel study. Comp Polit Stud. 2009;42(2):198–223. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Putnam RD. E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century. The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scand Polit Stud. 2007;30(2):137–174. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blalock HM (1984) Annual Review of Sociology, eds Turner RH, Short, Jr JF (Annual Reviews, Inc., Palo Alto, CA), Vol 10, pp 353–372.

- 4.Quillian L. Prejudice as a response to perceived group threat: Population composition and anti-immigrant and racial prejudice in Europe. Am Sociol Rev. 1995;60(4):586–611. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quillian L. Group threat and regional change in attitudes toward African Americans. Am J Sociol. 1996;102(3):816–860. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor MC. How white attitudes vary with the racial composition of local populations: Numbers count. Am Sociol Rev. 1998;63(4):512–535. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmid K, Al Ramiah A, Hewstone M. Neighborhood ethnic diversity and trust: The role of intergroup contact and perceived threat. Psychol Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0956797613508956. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allport GW. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies K, Tropp LR, Aron A, Pettigrew TF, Wright SC. Cross-group friendships and intergroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(4):332–351. doi: 10.1177/1088868311411103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90(5):751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright SC, Aron A, McLaughlin-Volpe T, Ropp SA. The extended contact effect: Knowledge of cross-group friendships and prejudice. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(1):73–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner U, Christ O, Pettigrew TF, Stellmacher J, Wolf C. Prejudice and minority proportion: Contact instead of threat effects. Soc Psychol Q. 2006;69(4):380–390. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models. 2nd Ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oishi S, Graham J. Social ecology: Lost and found in psychological science. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2010;5(4):356–377. doi: 10.1177/1745691610374588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hewstone M. Living apart, living together? The role of intergroup contact in social integration. Proc Br Acad. 2009;162:243–300. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. (2011) When Groups Meet: The Dynamics of Intergroup Contact (Psychology Press, Philadelphia)

- 17.De Tezanos-Pinto P, Bratt C, Brown R. What will the others think? In-group norms as a mediator of the effects of intergroup contact. Br J Soc Psychol. 2010;49(3):507–523. doi: 10.1348/014466609X471020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crandall CS, Eshleman A, O’Brien L. Social norms and the expression and suppression of prejudice: The struggle for internalization. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(3):359–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pettigrew TF. Intergroup contact theory. Annu Rev Psychol. 1998;49:65–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tropp LR, Bianchi RA. Valuing diversity and interest in intergroup contact. J Soc Issues. 2006;62(3):533–551. [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Knippenberg D, Haslam SA, Platow MJ. Unity through diversity: Value-in-diversity beliefs, work group diversity, and group identification. Group Dyn. 2007;11(3):207–222. [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Dick R, van Knippenberg D, Hägele S, Guillaume YRF, Brodbeck FC. Group diversity and group identification: The moderating role of diversity beliefs. Hum Relat. 2008;61(10):1463–1492. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adesokan AA, Ullrich J, van Dick R, Tropp LR. Diversity beliefs as moderator of the contact-prejudice relationship. Soc Psychol. 2011;42(4):271–278. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Norwegian Social Science Data Services (2002) European Social Survey Round 1 Data. Data file edition 6.2. Available at www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/download.html?r=1.

- 25.Lüdtke O, Marsh HW, Robitzsch A, Trautwein U. A 2 × 2 taxonomy of multilevel latent contextual models: Accuracy-bias trade-offs in full and partial error correction models. Psychol Methods. 2011;16(4):444–467. doi: 10.1037/a0024376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marsh HM, et al. Doubly-latent models of school contextual effects: Integrating multilevel and structural equation approaches to control measurement and sampling error. Multivariate Behav Res. 2009;44(6):764–802. doi: 10.1080/00273170903333665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, Zhang Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychol Methods. 2010;15(3):209–233. doi: 10.1037/a0020141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Binder J, et al. Does contact reduce prejudice or does prejudice reduce contact? A longitudinal test of the contact hypothesis among majority and minority groups in three European countries. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96(4):843–856. doi: 10.1037/a0013470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uslaner EM. Segregation and Mistrust: Diversity, Isolation, and Social Cohesion. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.