Abstract

Background/Aims

Many patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) often complain of fatigue. To date, only a few studies in Western countries have focused on fatigue related to IBD, and fatigue has never been specifically studied in Asian IBD patients. The aim of the present study was to investigate the fatigue level and fatigue-related factors among Korean IBD patients.

Methods

Patients in remission or with mild to moderate IBD were included. Fatigue was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue and the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Corresponding healthy controls (HCs) also completed both fatigue questionnaires.

Results

Sixty patients with Crohn disease and 68 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) were eligible for analysis. The comparison group consisted of 92 HCs. Compared with the HCs, both IBD groups were associated with greater levels of fatigue (p<0.001). Factors influencing the fatigue score in UC patients included anemia and a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Conclusions

Greater levels of fatigue were detected in Korean IBD patients compared with HCs. Anemia and ESR were determinants of fatigue in UC patients. Physicians need to be aware of fatigue as one of the important symptoms of IBD to better understand the impact of fatigue on health-related quality of life.

Keywords: Fatigue; Inflammatory bowel diseases; Crohn disease; Colitis, ulcerative

INTRODUCTION

Fatigue in chronic disease is defined as persistent, overwhelming sense of tiredness, weakness or exhaustion resulting in a decreased capacity for physical and/or mental work.1 Fatigue is not simply a part of a psychological comorbidity or illness behavior, but should be considered as a unique entity.2,3 Fatigue is one of the most important symptoms of many chronic diseases (i.e., primary biliary cirrhosis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus, sclerosing cholangitis, psoriatic arthritis, and multiple sclerosis).4-7

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which is a combined disease of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn disease (CD), is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. IBD shows a high incidence in young adults, and results in a life-long influence on these patients.8 Although the main clinical manifestations of IBD are known as abdominal pain and diarrhea caused by intestinal inflammation, many complain of systemic symptoms such as fatigue which can have a negative effect on the patient's physical well-being, functional status, and quality of life.9 Mitchell et al.10 demonstrated that fatigue as along with primary bowel symptoms were common in IBD patients. Also, it was reported in Norway recently that chronic fatigue is more frequent in patients with IBD than in healthy controls (HC) and is related to decreased quality of life.11,12 IBD associated fatigue is not only be severe but can also be the most debilitating part of the disease in some patients.

Various scales have been investigated and validated in order to determine patient perception and the severity of fatigue.13,14 Recently, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) has been validated for the IBD population in the United States.15 Also, the Korean version of the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) has been validated for the general population as well as for patients with cancer in Korea.16,17

Over the last decade, treatment options for patients with IBD have improved dramatically, with a huge improvement in the management of intestinal symptoms. However, subjective complaints by patients such as fatigue have been neglected and so its management has not been established. To date, only a few Western studies have focused on fatigue related to IBD. Although the incidence of IBD in Asia has increased rapidly in recent years, the prevalence of fatigue in Asian IBD patients has never been specifically studied. Thus, the primary aim of this study was to estimate the level of fatigue in Korean patients with IBD compared to those in HCs and second, to investigate the determinants of fatigue level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Subjects

This study was conducted in the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea from June 2012 to October 2012. Patients over 18 years of age and diagnosed with UC or CD based on standard endoscopic, radiographic, and histological criteria were included in this study. Activity of UC and CD was assessed by the Mayo score and Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI), respectively. CD patients with CDAI <150, 150 to 220, 220 to 450, >450 and UC patients with the Mayo score 0 to 2, 3 to 5, 6 to 10, 11 to 12 were considered to have remission, mild, moderate, and severe disease activities, respectively.18,19 Patients who were in remission or with mild to moderate disease activity were eligible for inclusion in this study. Patients with cognitive impairment, who did not consent to informed consent, or those who were considered by the investigator as not complying with the study procedure were excluded from the study. The data for HCs were collected from office workers without disease during the study period.

2. Clinical and sociodemographic data

Information on sociodemographic variables including age, gender, smoking habits, and body mass index were collected during history taking. Smoking history was categorized into two groups, current smoker and ex-smoker/never smoker. The data for clinical status, symptoms, and current medication use were obtained from disease activity indeces (Mayo score, CDAI) and medical records.

Information regarding fatigue was collected with the FACIT-F and BFI. The questionnaires were self-administered by the patients. Patients filled out the questionnaires in peace and quiet at the hospital outpatient clinic.

Disease phenotype was classified according to the Montreal Classification for CD patients. UC patients were classified into three subgroups: proctitis, left-sided colitis, and extensive colitis. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) level, hemoglobin (Hb) level, and reticulocyte distribution width (RDW) were assessed at the time when the fatigue level was estimated. Anemia was defined as Hb <12.0 g/dL for nonpregnant women and Hb <13.0 g/dL for men (World Health Organization definition).

3. Assessment of fatigue

FACIT instrument is a comprehensive compilation of questions that measure health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illnesses. FACIT-F is a subscale of the general questionnaire, the FACIT-G. It comprises 13 questions, the responses to which are each recorded on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores range from 0 to 52, with lower scores representing greater fatigue.15

The BFI consists of nine items on a single page. Fatigue and its interference with daily living are measured using numeric scales from 0 to 10. Three items ask subjects to describe their fatigue "now," at its usual level ("usual" fatigue), and at its worst level ("worst" fatigue) during the previous 24 hours. The descriptions range from "no fatigue" to "fatigue as bad as you can imagine." Six items ask how much fatigue has interfered with aspects of their life during the previous 24 hours, with scales ranging from 0 (did not interfere) to 10 (completely interfere). These aspects include general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work (both work outside of the home and daily chores), relationships with other people, and enjoyment of life. The global BFI score is calculated as the mean of the nine items.17 Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the BFI have been established previously.16

4. Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests, t-tests for parametric variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric variables were used to evaluate the differences in clinical characteristics and fatigue levels between the diagnostic groups. To extract sociodemographic and clinical factors related to fatigue scores, we used binary variables and otherwise bivariate correlation analysis. Linear regression analysis was performed using the enter method to evaluate the effects of demographic and clinical data (independent variables) extracted from the bivariate correlation analysis on the FACIT-F and global BFI (dependent variables). Data were analyzed separately in unadjusted and adjusted linear regression models. All tests were 2-sided and with a 5% significance level. All statics were performed using the Predictive Analytics Software, PASW version 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

5. Ethics

The study was performed according to the principles of Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital approved this study, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

RESULTS

1. Demographic and disease characteristics

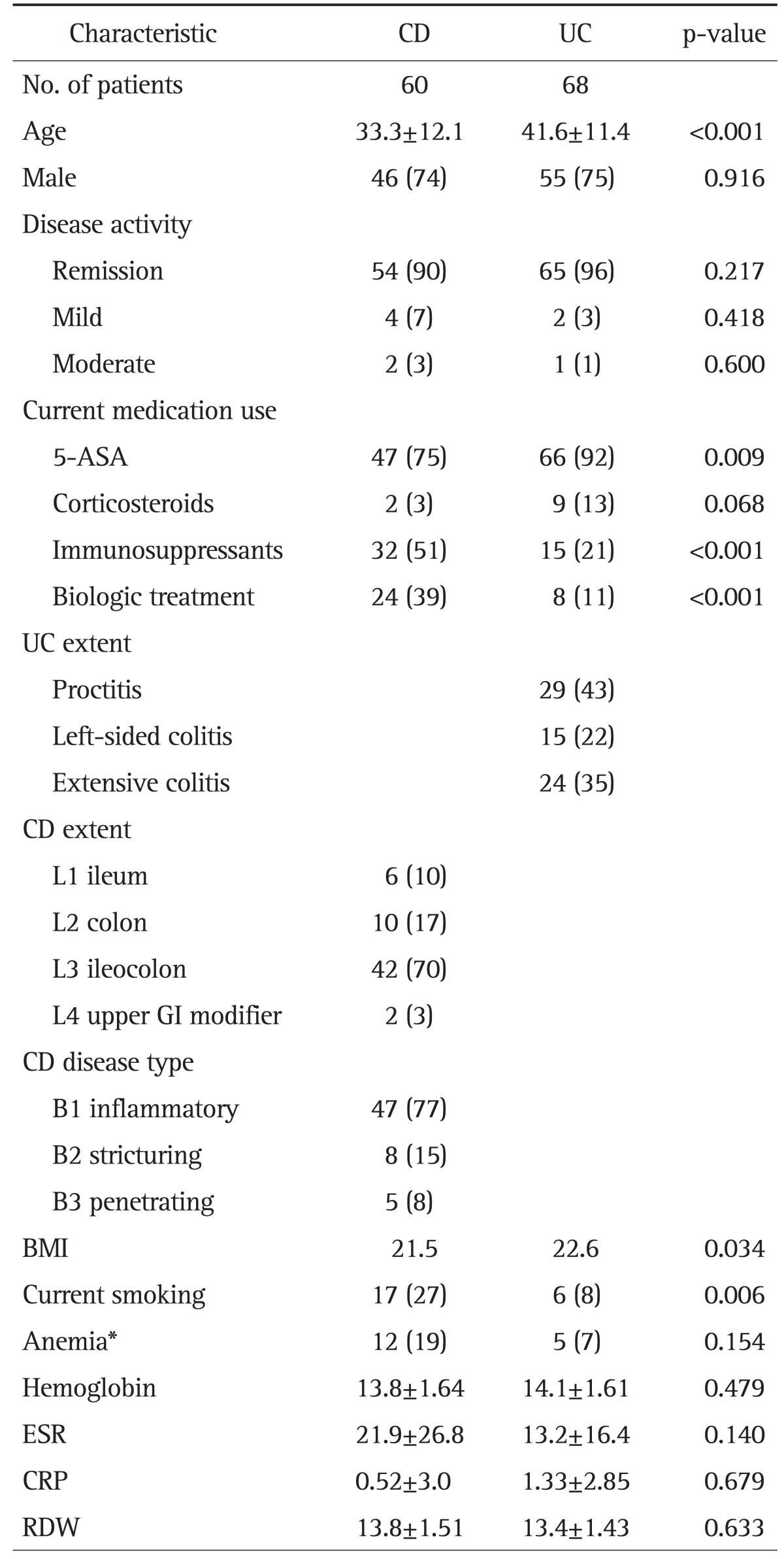

The demographic and disease characteristics of IBD patients are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between patients with IBD and HCs with regard to sex (male: CD 74% and UC 75% vs HCs 61%, p=0.080 and p=0.060, respectively) and mean age (CD 33.3 years and UC 41.6 years vs HC 37.7 years, p=0.060 and p=0.067, respectively). The mean CDAI of CD patients was 62.9±56.9. Most patients were in remission (90% in CD and 96% in UC).

Table 1.

Demographic and Disease Characteristics

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

CD, Crohn disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalisylic acid; GI, gastrointestinal; BMI, body mass index; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; RDW, reticulocyte distribution width.

*Hemoglobin <12.0 g/dL for nonpregnant women and hemoglobin <13.0 g/dL for men.

While the use of immunosuppressants and biologic agents was more frequent among CD patients, the use of 5-aminosalicylic acid was more frequent in UC patients. Anemia was found in 19% of CD and 7% of UC patients. There were no significant differences between CD and UC regarding the values of Hb, CRP, ESR, and RDW.

2. Fatigue in IBDs vs HCs

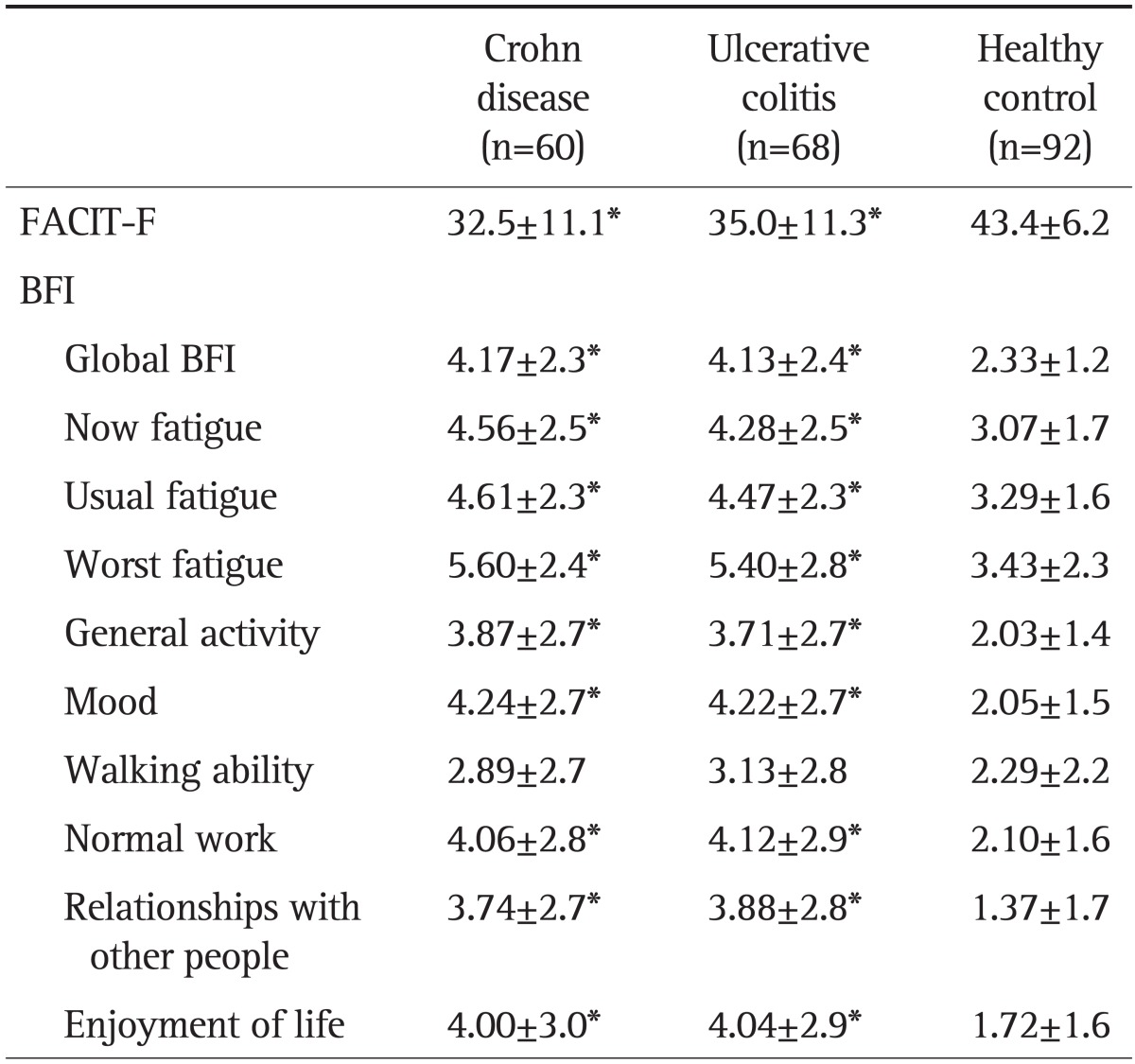

The mean scores of the FACIT-F and BFI are presented in Table 2. When comparing UC patients and CD patients, there were no differences in FACIT and BFI between the IBDs. However, in FACIT-F and all subdimensions of BFI except walking ability, both UC and CD patients showed significantly increased fatigue symptoms compared to HCs (all p<0.001). In the IBD patients with remission group, FACIT-F and all subdimensions of BFI except walking ability were also significantly higher compared with the HC group (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue and Brief Fatigue Inventory Scores between Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn Disease Patients and Healthy Controls

Data are presented as mean±SD. Significant differences were calculated by separately comparing the healthy controls with each diagnostic group.

FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory.

*p<0.001.

3. Factors influencing the fatigue score in IBD patients

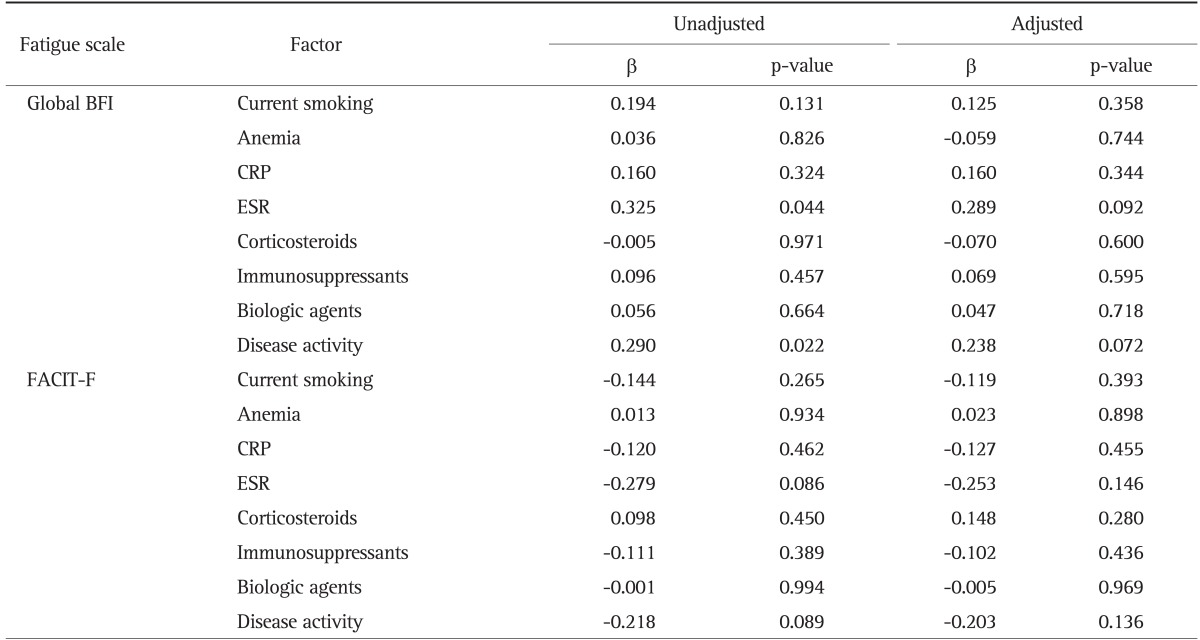

Factors predicting the fatigue scores in CD and UC patients are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. In patients with CD, ESR (p=0.044) and disease activity (p=0.022) were significantly correlated with Global BFI in the unadjusted regression analysis. However, after adjustment for age and sex, none of the collected factors had statistically significant impact on FACIT-F and global BFI.

Table 3.

Determinants of Fatigue Associated with Each Fatigue Scale for Crohn Disease

BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue.

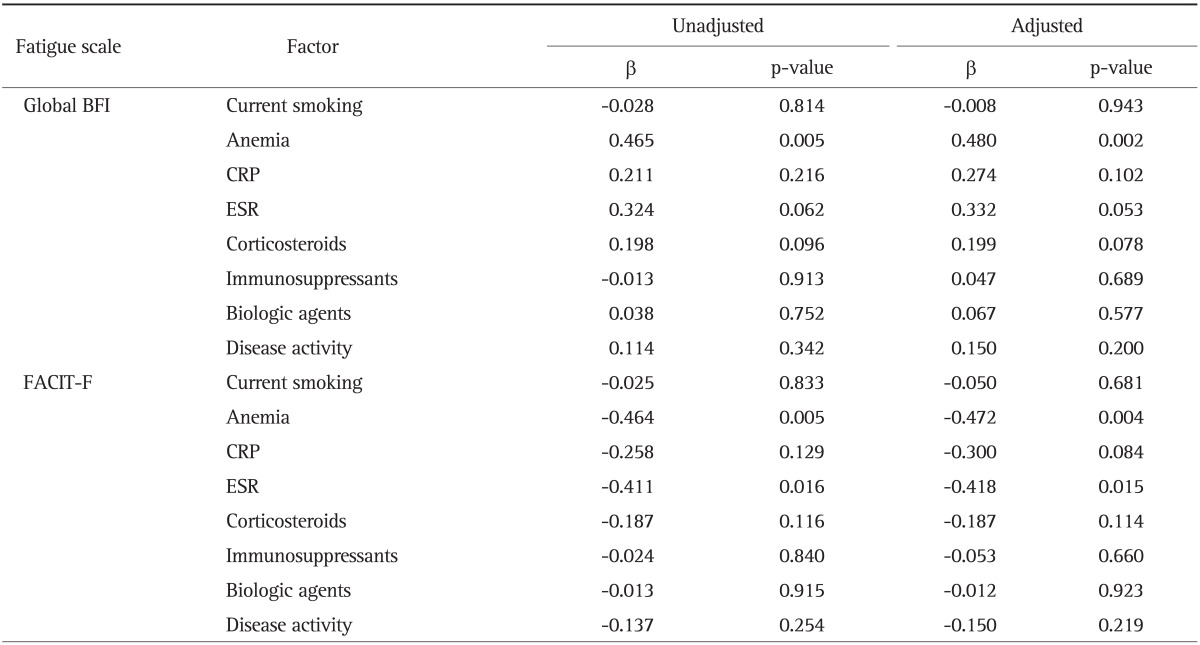

Table 4.

Determinants of Fatigue Associated with Each Fatigue Scale for Ulcerative Colitis

BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue.

In patients with UC, anemia was a significant determinant of both global BFI (p=0.002) and FACIT-F (p=0.004) after adjustment for age and sex. Among the laboratory data, only ESR was significantly correlated with FACIT-F (p=0.015).

DISCUSSION

As described in a 2010 systematic review by van Langenberg and Gibson,9 only a few studies have investigated fatigue as a primary end point in patients with IBD. However, all of these studies were conducted exclusively in Western countries. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the severity of fatigue and predictors for fatigue levels in Asian IBD patients.

We found that fatigue level is higher in patients with IBD than that in HC. There are several similar reports of other chronic conditions underlining this relation, such as primary biliary cirrhosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, sclerosing cholangitis, psoriatic arthritis, and multiple sclerosis.4-7 Recently, Jelsness-Jorgensen et al.11 reported similar results showing that systemic symptoms such as fatigue were more prevalent in patients with IBD than in HCs. They also demonstrated that chronic fatigue was associated with impaired health-related quality of life in IBD.12 Moreover, Minderhoud et al.20 revealed that fatigue was a highly prevalent symptom among IBD patients judged to be in remission or in those with mild and moderate disease at the time of investigation. We were able to confirm that Korean IBD patients are suffering from fatigue, in a similar manner to Western IBD patients.

In this study, the majority of UC patients were in remission. Our results showed that UC patients in remission had significantly higher fatigue levels than HCs. This finding is consistent with a previous study. Minderhoud et al.20 reported that IBD patients with quiescent disease had significantly higher levels of fatigue than the general population. It is possible that, even in the absence of ongoing inflammation, persistent fatigue may remain in a subgroup of IBD patients. It is also possible that chronic disease itself causes great stress to IBD patients and as a result, may affect their fatigue level.

In the unadjusted linear regression model, disease activity and ESR in patients with CD were correlated with fatigue level. This finding corresponds with a previous study which showed elevated fatigue was associated with active disease.21 However, in the adjusted model, there was a limit in identifying the relationship between disease activity, ESR and fatigue level. This may have been caused by the small sample size. Also, it could be another possibility that in CD, fatigue may be attributable to factors other than clinical activity.

In the present study, anemia was a determinant of both Global BFI and FACIT-F in patients with UC. This is in accordance with previous studies that demonstrated that a negative association between anemia and fatigue.22 Gasche23 revealed that chronic fatigue is a common symptom in anemic IBD patients. Furthermore, quality of life in anemic CD patients was improved after increasing Hb concentration by administration of intravenous iron and erythropoietin. Another study showed that the beneficial impact on quality of life derived from anemia correction in IBD patients is similar to the control of diarrhea.24 Successful treatment of anemia may decrease lethargy and increase a sense of well-being, as a result, affecting the fatigue level. In the aspect of fatigue, we need to meticulously correct anemia in IBD patients.

We found that ESR was correlated with FACIT-F in patients with UC. Tinsley et al.15 also showed that in UC, FACIT-F scores were correlated with ESR. These results may suggest that in UC, FACIT-F is sensitive to reflection of disease activity. Further studies are required to confirm the reliability of fatigue score as a complementary index of disease activity.

Our study has several limitations. First, the size of the study sample was too small. Further large-scale, multicenter studies are warranted for definitive identification of predictors for fatigue. Second, the FACIT-F questionnaire has not been validated for the Korean population, and BFI has not been validated for IBD patients. Third, subjects in the HC group were relatively younger than those in the UC group; this difference may have affected the evaluation of fatigue level. Fourth, psychologic aspects such as depression or anxiety which can affect the fatigue level were not considered.25

In conclusion, Korean IBD patients showed higher fatigue levels than HC. Anemia and ESR were determinants of fatigue level in UC patients. Further longitudinal studies need to address whether fatigue affects the outcome of actual patients, and whether fatigue level can be improved by controlling the determinants of fatigue.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Dittner AJ, Wessely SC, Brown RG. The assessment of fatigue: a practical guide for clinicians and researchers. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:157–170. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craig A, Tran Y, Wijesuriya N, Boord P. A controlled investigation into the psychological determinants of fatigue. Biol Psychol. 2006;72:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Linden G, Chalder T, Hickie I, Koschera A, Sham P, Wessely S. Fatigue and psychiatric disorder: different or the same? Psychol Med. 1999;29:863–868. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjornsson E, Simren M, Olsson R, Chapman RW. Fatigue in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:961–968. doi: 10.1080/00365520410003434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cella D, Yount S, Sorensen M, Chartash E, Sengupta N, Grober J. Validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy fatigue scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:811–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Omdal R, Waterloo K, Koldingsnes W, Husby G, Mellgren SI. Fatigue in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: the psychosocial aspects. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanca CM, Bach N, Krause C, et al. Evaluation of fatigue in U.S. patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1104–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vatn MH. Natural history and complications of IBD. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:481–487. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Langenberg DR, Gibson PR. Systematic review: fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:131–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell A, Guyatt G, Singer J, et al. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;10:306–310. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198806000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Torp R, Moum BA. Chronic fatigue is more prevalent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease than in healthy controls. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1564–1572. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Torp R, Moum BA. Chronic fatigue is associated with impaired health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:106–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisk JD, Ritvo PG, Ross L, Haase DA, Marrie TJ, Schlech WF. Measuring the functional impact of fatigue: initial validation of the fatigue impact scale. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18(Suppl 1):S79–S83. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.supplement_1.s79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC. The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315–325. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tinsley A, Macklin EA, Korzenik JR, Sands BE. Validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-F) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1328–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yun YH, Lee MK, Chun HN, et al. Fatigue in the general Korean population: application and normative data of the brief fatigue inventory. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yun YH, Wang XS, Lee JS, et al. Validation study of the korean version of the brief fatigue inventory. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stange EF, Travis SP, Vermeire S, et al. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: definitions and diagnosis. Gut. 2006;55(Suppl 1):i1–i15. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.081950a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minderhoud IM, Oldenburg B, van Dam PS, van Berge Henegouwen GP. High prevalence of fatigue in quiescent inflammatory bowel disease is not related to adrenocortical insufficiency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1088–1093. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graff LA, Vincent N, Walker JR, et al. A population-based study of fatigue and sleep difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1882–1889. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasche C, Lomer MC, Cavill I, Weiss G. Iron, anaemia, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2004;53:1190–1197. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasche C. Anemia in IBD: the overlooked villain. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:142–150. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200005000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomollón F, Gisbert JP. Anemia and inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4659–4665. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swain MG. Fatigue in chronic disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;99:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]