Abstract

Objective

Describe the development and psychometric validation of a brief scale (the Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI)) to evaluate insomnia disorder in everyday clinical practice.

Design

The SCI was evaluated across five study samples. Content validity, internal consistency and concurrent validity were investigated.

Participants

30 941 individuals (71% female) completed the SCI along with other descriptive demographic and clinical information.

Setting

Data acquired on dedicated websites.

Results

The eight-item SCI (concerns about getting to sleep, remaining asleep, sleep quality, daytime personal functioning, daytime performance, duration of sleep problem, nights per week having a sleep problem and extent troubled by poor sleep) had robust internal consistency (α≥0.86) and showed convergent validity with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Insomnia Severity Index. A two-item short-form (SCI-02: nights per week having a sleep problem, extent troubled by poor sleep), derived using linear regression modelling, correlated strongly with the SCI total score (r=0.90).

Conclusions

The SCI has potential as a clinical screening tool for appraising insomnia symptoms against Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria.

Keywords: Sleep Medicine, Psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Existing instruments used to evaluate insomnia lack specificity or do not permit assessment against the latest diagnostic criteria.

This study describes the development and validation of a new instrument (the Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI)) for use in everyday clinical practice.

The SCI is valid, reliable and sensitive to change in insomnia severity. Its brevity and appealing visual format permit rapid assessment and interpretation of poor sleep against contemporary clinical diagnostic criteria.

While we have used large surveys and treatment evaluation to assess SCI properties, more work is required to assess predictive validity with reference to independent clinical evaluation of insomnia disorder.

Introduction

Although insomnia is the most common of all mental health problems,1 it is seldom adequately assessed and treatment services are often poor.2 3 This perhaps reflects the perspective that insomnia is usually a symptom,4 coupled with minimal medical education on sleep and its disorders.5 However, there are three reasons why this perspective must now change. First, insomnia is not merely a symptom. It has for some time been proposed as a genuine diagnosis (see Harvey review),6 and recently the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) Work Group recognised that the previous dichotomy of primary versus secondary insomnia is not evidence based.7 8 Accordingly, DSM-5 now recommends that ‘insomnia disorder’ should be coded “whenever diagnostic criteria are met whether or not there is a co-existing physical, mental or sleep disorder”.9 Second, insomnia is not necessarily transient or benign. Once established, it is remarkably persistent,10 11 constituting a risk factor for the development of physical and mental health problems, notably depression,12–14 as well as adverse effects on quality of life.15 16 Chronic insomnia is also associated with high societal cost17 and is, for example, a robust predictor of work disability.18 Third, insomnia is treatable. There is a very substantial level 1 evidence-base, evaluating pharmacological and cognitive–behavioural therapies (CBTs),19 20 although the latter are very seldom available.3 21

Insomnia is ubiquitous,22 so it is important that clinicians, general practitioners in particular, have a reliable, valid and brief screening tool. A wide range of such instruments is a standard part of patient-centred care,23 for example, for depression,24 anxiety25 and alcohol problems.26 In the insomnia field, two scales in particular are widely used: the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)27 and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).28 The PSQI is an established research tool, which has a cut-off score indicative of sleep disturbance. However, it lacks specificity for insomnia. The ISI is very sound psychometrically, and is more specific and based on DSM-IV criteria for insomnia. It is used in the main to select people for clinical trials and as an outcome measure.

In this paper, we present a further measure (the Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI)) that may have some useful features. The SCI is informed by the development phase for DSM-5 insomnia disorder,7 8 coupled with published research diagnostic criteria29 and recommended quantitative parameters for sleep disturbance.30 In keeping with DSM-5, the SCI also evaluates associated daytime factors, which are important drivers of clinical symptoms22 and should be incorporated in insomnia measurement.15 16 31 In terms of utility, the SCI is brief but versatile. It yields (1) a dimensional perspective on sleep quality: on an intuitive, global scale where higher scores represent better sleep; (2) a visual profile of night-time and daytime symptoms that the clinician can use in consultations and (3) indicative cut-off points for clinically-significant insomnia. This paper summarises the development and evaluation of the SCI across several studies, and in doing so addresses two major questions. First, does the SCI have adequate psychometric properties? Second, is it possible to derive an even briefer, short form, SCI that has similar psychometric characteristics?

Methods

Sample characteristics

Data are reported from five validation studies (total n=30 941; 71% female) in which SCI items were administered. The Great British Sleep Survey (GBSS) was an open access, web-based survey completed by adults (18+years) with a UK postcode yielding data on 12 628 participants (72% female; mean age=38.7 years (SD=14.5)) between February 2010 and August 2011.32 The GBSS+ was a revision of the GBSS, extended to any valid zip code worldwide, from May 2011 to March 2012 (n=11 017; 68% female; 42.3 years (16.5)). The TV sample was obtained in response to a network programme (the Food Hospital, Channel 4) on the sleep benefits of tart cherry juice (n=6876; 76% female, 36.4 years (13.3)). Glasgow Science Centre data (n=256; 56% female, 40.3 years (14.9)) were collected in 2009–2010 during a study which assessed the relationship between salivary α-amylase, sleep pressure and diurnal preference.33 Finally, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) sample comprised 164 participants (72% female, 48.9 years (13.7)) recruited into a placebo-controlled evaluation of CBT for insomnia.34 Ethical agreement concerning the latter two studies is provided in the source manuscripts. For the open access web surveys, participation was covered by the site terms.

Across our combined largest samples (GBSS, GBSS+, TV), women were slightly younger than men (38.5 (14.9) vs 40.1 (14.7) years; t(27 638)=7.94, p<0.0001) and the great majority was in average or better physical health (86%) and mental health (82%; 5-point scale: 0 ‘very good’, 1 ‘good’, 2 ‘average’, 3 ‘poor’ and 4 ‘very poor’). Respondents who made some use of prescription sleeping pills (9.1%) were 7 years older than those who did not (46.2 (15.1) vs 39.1 (15.1) year, t(20 813)=19.6, p<.0001) and had a substantially poorer SCI score (8.56 (4.93) vs 15.6 (7.80), t(20 813)=38.8, p<0.0001). Of the total sample, 18.1% took over-the-counter sleep aids (OTCs), and more than one-third of those taking sleeping pills also used OTCs.

Design and measurement

This is a psychometric scale development study. Standard approaches to the appraisal of validity, reliability and sensitivity were applied, making appropriate selection among the available datasets. These methods and datasets will be introduced in an integrated way in subsequent sections, so that the research process can be more clearly expressed and understood.

Results

Development of the SCI

Content validity

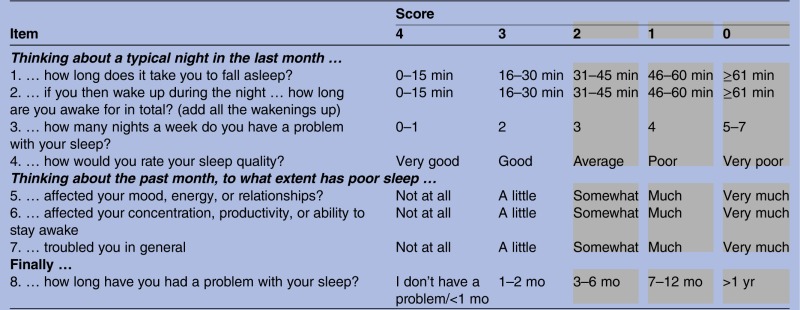

An eight-item scale was developed (see appendix) based on DSM-5 workgroup draft criteria that were available at the time (in 2010).7 8 At that stage, a consultation process was underway and draft information was posted on the American Psychiatric Association website. Consequently, the SCI items generated comprised two quantitative items on sleep continuity (item 1, getting to sleep; item 2, remaining asleep), two qualitative items on sleep satisfaction/dissatisfaction (item 4, sleep quality; item 7, troubled or not), two quantitative items on severity (item 3, nights per week; item 8, duration of problem) and two qualitative items on attributed daytime consequences of poor sleep (item 5, effects on mood, energy or relationships (personal functioning); item 6, effects on concentration, productivity or ability to stay awake (daytime performance)).

Validated quantitative criteria for sleep disruption (eg, 31–45 min to fall asleep) served as responses for sleep continuity items 1 and 2.8 29 30 Items 5 and 6 on daytime effects were derived by principal components analysis (PCA; Varimax rotation) of six individual proposed DSM-5 impact areas, using combined datasets (GBSS, GBSS+, TV, RCT: valid n=29 650). PCA yielded satisfactory Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO=0.874) and Bartlett (p<0.0001) statistics. Iteration converged after three rotations. A two component model (derived from inspection of the scree plot and a criterion for associated variance ≥10%) explained 75.8% of total variance, with item loadings ≥0.60. Component 1 (eigenvalue=3.83; 63.8% of variance) comprised ‘mood’ (loading=0.812), ‘energy’ (0.651) and ‘relationships’ (0.859), and was subsequently named ‘personal functioning’. Component 2 (eigenvalue=0.72; 12.0% of variance) comprised ‘concentration’ (0.719) and ‘get through work’ (0.724), and ‘stay awake’ (0.875) may be regarded as ‘daytime performance’. PCA offered a relatively pure solution, although ‘energy’ also loaded significantly on component 2 (0.519).

We then investigated the inter-relationships of our eight SCI items using the same methodology, but applying this time a minimum item loading of 0.40, to permit incorporation of all eight items. PCA with Varimax Rotation (KMO=0.888; Bartlett, p<0.0001) yielded a two component solution (66.4% explained variance). Component 1 (eigenvalue=4.256, 53.2% variance), named ‘sleep pattern’, comprised items 1, 2, 3, 4 and 8 with factor loading ranging from 0.453 to 0.776. Component 2 (eigenvalue=1.06, 13.2% variance), named ‘sleep-related impact’, comprised item 5 (factor loading 0.886) and item 6 (0.911). Consistent with clinical presentation, concerns about sleep (item 7) loaded significantly and similarly on ‘sleep pattern’ (0.616) and ‘sleep-related impact’ components (0.576).

Response format

Each item was scored on a 5-point scale (0–4), with lower scores, in the 0–2 range, reflecting putative threshold criteria for insomnia disorder (shaded area: see appendix). The clinician can then see at a glance the profile of possible concerns. The possible total score ranges from 0 to 32, with higher values indicative of better sleep. However, scores can be readily transformed into a more intuitive 0–10 SCI range, either by dividing the total by 3.2, or by using an online version with automated scoring, which is available free of charge (http://www.sleepio.com/clinic/).

Concurrent validity and association with related domains

Data from the Science Centre sample demonstrated that the SCI correlates inversely with the PSQI (r=−0.734) and the ISI (r=−0.793), suggesting measurement properties consistent with these related measures. There was also a small but significant association of sleep condition with self-rated physical health (r=0.222), and an association also with mental health (r=0.335). Using more specific measures, in the Science Centre sample, correlation of the SCI with symptoms of depression (r=−0.426) and anxiety (r=−0.400) on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale35 was modest, and greater than we observed in our RCT sample (on the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale36: depression (r=−0.267), anxiety (r=−0.236) and stress (r=−0.263)).

We have not at this stage tested the discriminant validity of the SCI against clinical diagnosis of insomnia disorder. As a first step, however, using our Science Centre sample, we tested the concurrent validity of SCI cut-offs (score ≤16), reflecting the minimum criteria for putative insomnia disorder (see appendix), against published, validated ISI cut-off scores. We first categorised our sample according to ISI ranges (ISI score=0–14, reflecting ‘no insomnia disorder’ (n=228) vs ‘probable insomnia disorder’ ISI score=15–28, n=27)) and conducted an independent t test on SCI total score. The mean SCI values for the ‘probable insomnia disorder’ category were 10.7 (SD=5.3) vs 22.9 (SD=6.2) for ‘no insomnia disorder’ (t=9.86, p<0.0001). Applying an SCI cut-off ≤16, 89% of the sample was correctly identified as having ‘probable insomnia disorder’ (ISI scores of ≥15), while an SCI score of >16 correctly identified 82% of those with ‘no insomnia disorder’. These findings provide further evidence of concurrent validity for the SCI and help to confirm that a score of ≤16 on the SCI seems reasonable to detect possible insomnia disorder.

Internal consistency

Cronbach's α for the GBSS sample was strong at 0.857 (range of α-if-item-deleted 0.822–0.860). Replication of these internal consistency data was obtained from the GBSS+ sample (α=0.865). The mean corrected item-total correlation was moderate (r=0.620), indicating a substantial unique variance per item (shared variance=38%).

Sensitivity to change

We have previously reported that the SCI is sensitive as a measure of treatment outcome.34

Short-form version of the SCI

Although the SCI is brief, in clinical practice ultra short-form scales are often helpful (eg, generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) 2-items).37 Accordingly, we conducted a stepwise linear regression analysis to determine which subset of items (independent variables) explained the greatest proportion of variance in the dependent variable, SCI total score. A two-item (SCI-02), comprising item 3 ‘how many nights’ (standardised β=0.515) and item 7 ‘troubled you in general’ (β=0.491), together predicted 82% of variance (adjusted R2=0.820) in the full scale SCI (R2 change=0.672 + 0.148; F(227 637)=62 770, p<0.0001). As a check on the independence of residuals, we computed the Durbin-Watson statistic, which was found to be 1.80, suggesting no serial correlation. The SCI-02 also correlated strongly with the SCI score total (r=0.904).

Discussion

A prerequisite to improved insomnia care is the availability and regular use of reliable and valid insomnia assessment. Only then can a clinical problem be recognised as distinct from normal variation, and a persistent problem be differentiated from a transient one. We have reported here the development and preliminary validation of the SCI, a DSM-5 compliant, brief screening measure that may be fit for such purposes. Results indicate that the SCI is internally consistent, sensitive to change and correlates strongly with established screening instruments, known to be sensitive to clinical insomnia (PSQI and ISI). PCA revealed a two-component solution (66% of the variance), reflecting the underlying complaint of insomnia; that is, concerns about sleep pattern and concerns about the impact of poor sleep, both of which need to be addressed in clinical practice. The derived two-item short-form version, focusing on the severity of the presenting complaint coupled with frequency of the sleep problem, correlated strongly with total SCI score and we would suggest that these might be the lead questions for a clinician to use in the context of their consulting room practice.

Of course, further work is required, particularly real-world studies of how the SCI might be used in population screening and in the evaluation of outcome following an episode of care. While comparisons with ISI cut-offs provide evidence of concurrent validity and indicate that an SCI score ≤16 may help detect probable insomnia disorder, studies of predictive validity with reference to independent clinical evaluation of insomnia disorder (the gold standard) are essential before firm conclusions can be made.

It should be noted that over half of the respondents to our online surveys screened positive for possible insomnia disorder. These, of course, are not prevalence data as we did not adopt a formal population sampling approach. Nevertheless, the inevitable bias of these open access surveys towards those with sleep concerns does permit us (1) to profile many respondents against criteria; (2) to conduct powerful analyses of the properties of the SCI and (3) to make comparisons with sizeable cohorts of good sleepers. Importantly, for our Science Centre sample, approximately 10% scored in the probable insomnia disorder range (ISI score ≥15), consistent with prevalence data,2 providing further support for our ISI–SCI concurrent validity analysis.

Furthermore, a limitation of the SCI is that it does not contain specific questions relating to early morning awakenings (EMA; premature awakening with inability to return to sleep)—a symptom which has recently been incorporated into DSM-5 criteria. While established insomnia questionnaires, including the ISI28 and Athens Insomnia Scale,37 probe perceived severity of EMA, quantitative values for EMA, to our knowledge, are yet to be defined. To some extent, SCI item 2 on wakefulness during the night may capture this symptom, complaint, but we recommend that the clinician follows up a ‘positive’ answer to locate the nature and temporal position of wakefulness during the sleep period. Moreover, other core DSM-5 criteria do not feature as SCI items (eg, the sleep difficulty occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep; the insomnia is not better explained by and does not occur exclusively during the course of another sleep-wake disorder; and the insomnia is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance). However, these items are not easy to probe unambiguously with a self-completed psychometric instrument and would require careful scrutiny by a treating clinician. It is, of course, possible that sleep disorders other than insomnia (eg, circadian rhythm sleep disorders, sleep-breathing disorders) may also lead to low scores on the SCI. Thus, the SCI should be viewed as an insomnia screening tool, consistent with features of DSM-5, but requiring careful follow-up in clinical practice to fully define the nature of sleep disturbance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The copyright associated with the SCI is reserved by Sleepio Limited, and is licensed free for non-commercial use on condition under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 international license.

Appendix

Appendix: The sleep condition indicator

|

Scoring instructions:

Add the item scores to obtain the SCI total (minimum 0, maximum 32).

A higher score means better sleep.

Scores can be converted to 0–10 format (minimum 0, maximum 10) by dividing total by 3.2.

Item scores in grey area represent threshold criteria for Insomnia Disorder.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were engaged in the following study tasks: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: CAE is the Clinical and Scientific Director of Sleepio Ltd., and PH is co-founder, shareholder and board member of Sleepio Ltd. SDK has acted as a consultant for Sleepio Ltd.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was acquired for the experimental studies by the host institution and for the open access web surveys, participation and consent was covered by the site terms.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O'Brien M, et al. Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households, 2000. London: The Office for National Statistics, HMSO, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morin CM, Benca R. Chronic insomnia. Lancet 2012;379:1129–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falloon K, Arroll B, Elley CR, et al. The assessment and management of insomnia in primary care. BMJ 2011;342:d2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichstein K. Secondary insomnia: a myth dismissed. Sleep Med Rev 2006;10:3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stores G, Crawford C. Medical student education in sleep and its disorders. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1998;32:149–53 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey AG. Insomnia: symptom or diagnosis? Clin Psychol Rev 2001;21:1037–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds CF, Redline S. The DSM-V sleep-wake disorders nosology: an update and an invitation to the sleep community. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;15:9–10 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. 2010. M00 Insomnia Disorder. DSM-5 Development Web site. http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=65#/Updated 2 June.

- 9.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edn Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morin CM, Belanger L, LeBlanc M, et al. The natural history of insomnia: a population-based 3-year longitudinal study. Arch intern Med 2009;169:447–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green M, Benzeval M, Espie CA, et al. The longitudinal course of insomnia symptoms: inequalities by gender and occupational class among two different age cohorts followed for 20 years in the West of Scotland. Sleep 2012;35:385–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep 2009;32:491–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Pejovic S, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1980–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord 2011;135:10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kyle SD, Morgan K, Espie C. Insomnia and health-related quality of life. Sleep Med Rev 2010;14:69–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leger D, Bayon V. Societal costs of insomnia. Sleep Med Rev 2010;14:379–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sivertsen B, Overland S, Neckelman D, et al. The long-term effect of insomnia on work disability: the HUNT-2 historical cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:1018–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, et al. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: update of the recent evidence (1998–2004). Sleep 2006;29:1398–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riemann D, Perlis ML. The treatments of chronic insomnia: a review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioral therapies. Sleep Med Rev 2009;13:205–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Espie CA. ‘Stepped care’: a health technology solution for delivering cognitive behavioral therapy as a first line insomnia treatment. Sleep 2009;32:1549–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley JP, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med 2006;7:123–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NICE Clinical Guideline 123. 2011. Common mental health disorders: identification and pathways to care. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13476/54520/54520.pdf.

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16:606–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonnell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1789–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morin CM. Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, et al. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep. 2004;27:1567–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Taylor DJ, et al. Quantitative criteria for insomnia. Behav Res Ther 2003;41:427–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moul DE, Hall M, Pilkonis PA, et al. Self-report measures of insomnia in adults: rationales, choices, and needs. Sleep Med Rev 2004;8:177–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espie CA, Kyle SD, Hames P, et al. The daytime impact of DSM-5 insomnia disorder: comparative analysis of insomnia subtypes from the Great British Sleep Survey (n=11, 129). J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:e1478–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardani M, Miller CB, Biello S, et al. The association of sleepiness and diurnal preference with salivary amylase activity. Abstracts of 4th International Congress of WASM & 5th Conference of CSS/Sleep Med 2011;12(Suppl.1):S1–130 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Espie CA, Kyle SD, Williams C, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep 2012;35:769–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2005;44:227–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:317–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paprrigopoulos TJ. Athens insomnia scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res 2000;48:555–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.