Abstract

Preeclampsia (PE), characterized by proteinuric hypertension and occurring in 2–3 % of all pregnancies, is one of the leading causes of maternal, fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The etiology of PE still remains unclear and current treatments for this devastating disorder are still limited to symptomatic therapies. Placental oxidative stress may be a key intermediate step in the pathogenesis of PE; it has been related to excessive secretion of multiple antiangiogenic factors, mainly soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and soluble endoglin (sEng). The nuclear factor-erythroid 2-like 2 (Nrf2) pathway is one of the most important systems that enhance cellular protection against oxidative stress. Nrf2 serves as a master transcriptional regulator of the basal and inducible expression of a multitude of genes encoding detoxification enzymes and antioxidative proteins. Evidence for a link between Nrf2 and restoring the balance between pro- and antiangiogenic factors mainly through its downstream target protein heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) has lately been discussed. HO-1 metabolizes heme to biliverdin, iron and carbon monoxide (CO). CO enhances vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) synthesis in vascular smooth muscle and promotes its relaxation and hence vasodilatation. In addition, HO-1 has been shown in vitro to inhibit the production of sFlt-1. A recent animal study demonstrated that the induction of HO-1 in a mouse model of PE attenuates the induced hypertension in pregnant mice. This provides compelling evidence for the protective role of Nrf2/HO-1 in pregnancy and identifies this pathway as a target to treat women with PE. We summarize the recent findings on the involvement of Nrf2 in the pathogenesis of PE, and provide an overview of the possible beneficial effects of Nrf2 inducers in PE.

Key words: preeclampsia, Nrf2, heme oxygenase-1

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

Präeklampsie (PE) ist charakterisiert durch Gestationshypertonie und Proteinurie; mit einer Prävalenz von 2 bis 3 % zählt sie zu den häufigsten Schwangerschaftserkrankungen. Präeklampsie gehört zu den führenden Ursachen für fetale, neonatale und mütterliche Morbidität und Mortalität. Die Ätiologie dieses Syndroms ist noch unbekannt, und die Behandlung richtet sich daher nach den Symptomen. Studien haben gezeigt, dass oxidativer Stress in der Plazenta eine wichtige Rolle bei der Pathogenese der Präeklampsie spielen könnte. Plazentaler oxidativer Stress könnte zu einer erhöhten Freisetzung von antiangiogenetischen Faktoren wie fms-like Tyrosine Kinase-1 (sFlt-1) und Soluble Endoglin (sEng) führen. Der Nuclear-Factor-Erythroid-like-2-(Nrf2-)Signalweg ist ein wichtiges System, das die Zellen vor oxidativen Stress schützt. Die Expression vieler antioxidativer Enzyme wird von Nrf2 verstärkt. Es wurde ferner berichtet, dass das Nrf2-System eine Rolle bei der Regulierung der Balance von pro- und antiangiogenen Faktoren spielt, indem es das Zielprotein Hämoxygenase-1 (HO-1) hochreguliert. HO-1 katalysiert die Oxidation von Häm zu Biliverdin, Eisen und Kohlenmonoxide (CO). CO stimuliert die Proteinsynthese des vaskulären endothelialen Wachstumsfaktors VEGF in vaskulären glatten Muskelzellen, und kann auch die Relaxation der glatten Muskulatur (Gefäßerweiterung) induzieren. Zudem kann HO-1 in vitro die Freisetzung von sFlt-1 hemmen. Darüber hinaus wurde kürzlich in Studien gezeigt, dass die Aktivierung von HO-1 in verschiedenen Tiermodellen für Präeklampsie zu einer Blutdrucksenkung führt. Diese Studien zeigen, dass der Nrf2/HO-1 Signalweg eine präventive Rolle bei Präeklampsie spielen könnte. Ziel dieser Übersichtsarbeit ist es, die neuesten wissenschaftlichen Studien zur Beteiligung von Nrf2 an der Pathogenese von Präeklampsie zusammenzufassen. Zudem möchten wir einen Überblick über das therapeutische Potenzial von Nrf2-Aktivatoren bei der Präeklampsie geben.

Schlüsselwörter: Präeklampsie, Nrf2, Hämoxygenase-1

Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy complicate 5–10 % of pregnancies and can lead to serious maternal illness or death. Preeclampsia (PE), the most serious of these disorders, is the second leading cause of maternal death worldwide, and results in 63 000–72 000 maternal deaths each year. Over 99 % of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries 1. Although PE complicates 2–3 % of pregnancies in UK, PE is still the second leading cause of maternal death with an incidence of about 0.83 deaths per 100 000 maternities in UK for 2006–2008 2.

According to the criteria of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), PE is characterized clinically by a new onset of hypertension (≥ 140/90 mmHg) and proteinuria (≥ 300 mg/day) after 20 gestational weeks 3. Advanced-stage clinical symptoms include seizures, renal failure, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and/or hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome.

PE has an impact on the health of both the mother and the fetus, and has also a long-term impact on health. Systemic reviews and meta-analysis showed that women with PE are twice as likely to develop cardiovascular disease later in life 4, 5. Although the estimated 10-year cardiovascular disease risk is low (less than 5 %) after delivery, cardiovascular disease risk is expected to increase rapidly with increasing age 6.

PE has been termed the “disease of theories”, reflecting the confusion about the etiology and pathophysiology of PE 7. Nevertheless, it appears likely that the placenta releases substances that cause endothelial dysfunction in the maternal blood vessels of susceptible women. It involves generalized damage to the maternal endothelium in the kidneys, liver, and blood vessels, leading to blood pressure elevation, the most conspicuous sign of the disease 8.

Placental oxidative stress is considered to promote the release of the aforementioned factors that may be involved in endothelial cell dysfunction. The principal pathology appears to be insufficient uteroplacental blood supply 9, which mainly results from reduced trophoblast invasion.

The shallow trophoblast invasion in PE results in defective spiral artery remodeling followed by high-resistance vessels and reduced placental perfusion 10. The consequence is retention of vasoreactivity in the myometrial segments of these arteries, leading to intermittent perfusion of the intervillous space and hence to fluctuating oxygen concentrations that results in oxidative stress within the placenta 11.

To counteract oxidative stress, the placenta produces several antioxidants including heme oxygenases (HO-1, HO-2), copper zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) 12.

Exposure to reactive oxygen species switches on a battery of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes. This coordinated response is regulated via the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) contained within the promoter regions of the so-called “safeguard” genes 13, 14. Activation of the nuclear factor-erythroid 2-like 2 (Nrf2) as a consequence of oxidative stress or vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) initiates and enhances the transcription of these “safeguarding” genes, thus protecting the cells against oxidative stress as well as a wide range of other toxins 15.

Wruck et al. (2009) presented the first experimental data showing that Nrf2 is exclusively active within the cytotrophoblast of the preeclamptic placenta, strongly suggesting that these cells suffer from oxidative stress caused by excess production of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) 16. Moreover, induction of Nrf2 increases the protein levels of VEGF via its target protein HO-1 and its metabolite carbon monoxide (CO) 17.

Because of Nrf2’s ability to induce protein synthesis of VEGF, the impairment of Nrf2 signaling in the extravillous trophoblast (EVT) of preeclamptic women has been recently suggested as limiting the ability for invasion of these cells 18.

The present review aims to highlight recent research progress in the field of the transcription factor Nrf2 with regard to its role in the development of PE and its potential use as a therapeutic target.

Oxidative Stress in PE

In normal pregnancies, the production of ROS and lipid peroxidation increases toward the end of pregnancy 19, whereas antioxidant capacity increases in order to maintain oxidative balance throughout pregnancy 19. In addition, a normal pregnancy enhances the general inflammatory response, especially toward the end of the third trimester 20. This includes the activation of monocytes, granulocytes and lymphocytes during the third trimester, all of which produce ROS 21.

Oxidative stress has been implicated in promoting PE. The placental stresses of PE mostly develop in early onset disease and stimulate the release of circulating factors that cause the maternal syndromes 20. It has been shown that the main manifestations of this syndrome – represented by hypertension and proteinuria – are secondary to diffuse endothelial dysfunction 22. Oxidative stress occurs when the production of reactive oxygen species overwhelms the intrinsic antioxidant defenses. It may induce a wide range of cellular responses, depending on the severity of the episode and the compartment in which ROS are generated 20. Indisputable evidence of placental oxidative stress in PE, including increased concentrations of protein carbonyls, lipid peroxides, nitrotyrosine residues, and DNA oxidation 21, confirm this theory.

What causes this oxidative stress? It is thought to be vascular, because early onset PE is associated with a weak invasion of the EVT and consequently deficient remodeling of the spiral arteries 23, 24. In normal pregnancies, the remodeling of the uterine and placental vessels generates free radicals, which are normally controlled by appropriate antioxidant levels. In PE, it has been observed that ROS are increased, and the levels of several detoxifying enzymes are reduced 25. Stepan et al. (2004) proved a correlation between impaired uteroplacental perfusion and decreased plasma antioxidant capacity. They showed that second-trimester pregnancies with pathological uterine perfusion are characterized by decreased total antioxidant capacity in the maternal circulation 26. Their results added strength to the two-stage hypothesis whereby decreased plasma antioxidant capacity as a result of reduced placental perfusion only reflects stage one and additional factors such as maternal genetic susceptibility or dyslipidemia are required to promote the later disease 27.

In addition, because of the high contractility of the spiral artery of the myometrial segment, it is hypothesized that the ensuing high-pressure flow causes hydrostatic damage to placental villi and perfusion due to intermittent pulses of fully oxygenated arterial blood; the latter is presumed to lead to the fluctuations in oxygen delivery that predispose to oxidative stress 20. According to Redman (2011), the placental problem, at least in the early stages, is due neither to hypoxia nor to reduced flow but rather to oxidative stress and physical disruption of placental villous architecture 20. This hypothesis is supported by in vitro experiments; Hung et al. (2001) indicated that hypoxia/reoxygenation is a potent inducer of oxidative stress in term placental explants, much more than hypoxia alone 28.

Nrf2/ARE System

Nrf2 is a member of the capʼnʼcollar transcription factor family with a conserved basic region-leucine zipper domain that binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), a regulatory element in promoter regions of several genes encoding phase II detoxification enzymes (e.g. glutathione S transferases) and antioxidant proteins (e.g. NADPH quinone oxidoreductase – NQO1 and HO) 15.

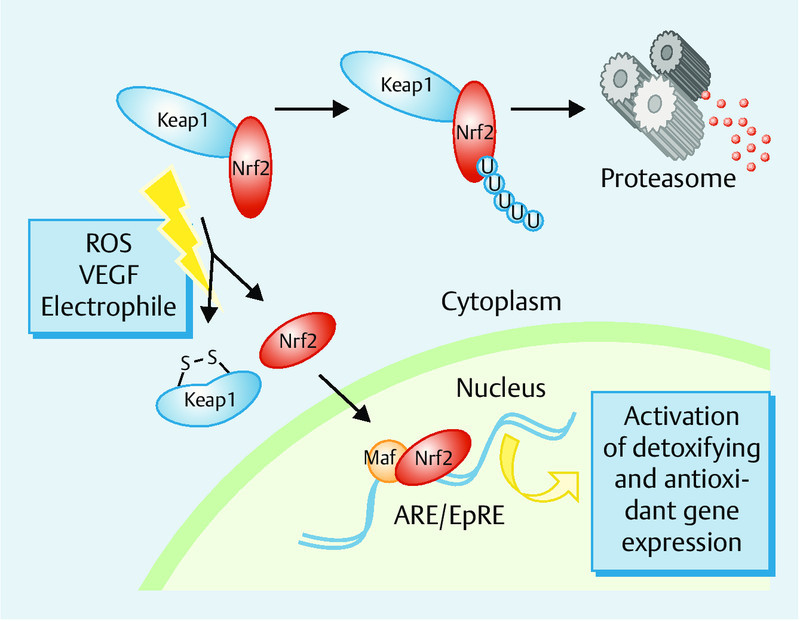

Under normal conditions, Nrf2 is bound to Keap1, resulting in lowered levels in the cells because of rapid proteasomal degradation. Keap1 acts as a negative regulator of Nrf2 and as a sensor of oxidative and/or electrophilic stress. Once reactive thiols of Keap1 are modified by electrophiles or ROS, ubiquitination of Nrf2 is readily inhibited, thereby rescuing newly synthesized Nrf2 from proteasomal degradation and allowing for its accumulation in the nucleus 29 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic presentation of Nrf2-ARE system. The activity of Nrf2 is tightly regulated by the negative regulator Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap-1). Keap-1 is a cytoskeletal protein, binds to Nrf2 and induces its degradation. Upon exposure of the cells to oxidative stress or VEGF, Nrf2 dissociates from Keap1, translocates to the nucleus and ultimately activates the antioxidant response element (ARE)-dependent gene expression.

Nrf2 mediates a broad-based set of adaptive responses to intrinsic and extrinsic cellular stresses 29. Several studies have reported that this factor exerts cellular protection against a wide variety of toxic insults (carcinogens, electrophiles, ROS, inflammation, calcium disturbance, ultraviolet light, and cigarette smoke) 30. Our study group recently showed that VEGF has the ability to activate the Nrf2 system without intracellular ROS production 17. Results from animal models highlighted the impact of this factor in several pathological conditions: hemolytic anemia, smoke-induced emphysema, and neurodegenerative disorders (traumatic brain injury, ALS, and Alzheimerʼs) 30, 31. More recently, the involvement of this factor in the pathogenesis of PE has been discussed 16, 17, 18, 32, 33.

The antioxidative effects of Nrf2 in different biological and pathological conditions are well accepted. However, Nrf2 is still under intensive research because of the growing evidence that the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway also cross-talks with other molecular pathways and transcription factors 29.

Nrf2 in Preeclampsia

Wruck et al. (2009) 16 provided the first experimental data that Nrf2 is active exclusively within cytotrophoblasts of preeclamptic placentas, strongly suggesting that these cells suffer from oxidative stress caused by excessive production of ROS.

Cell models have also served as a useful tool to study Nrf2 properties against cytotoxicity. Nrf2 has been studied in cell models related to pregnancy and placental development, such as human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) 34 and BeWo cells (a model for syncytiotrophoblast formation 17. The activation of HO-1 by Nrf2 protected cells against oxidative damage. Interestingly, the Nrf2 inducer used in this study has been shown to exert a positive effect on the activation of VEGF, and the disruption of Nrf2 signaling impairs the angiogenic capacity of trophoblasts 17 and endothelial cells 34.

Loset et al. (2012) analyzed the single genes, canonical pathways and gene-gene networks that are likely to play an important role in the pathogenesis of PE. They reported that the Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress response was overrepresented in the decidua of patients with PE 35, consistent with the results from the first study of Wruck et al. (2009) on preeclamptic placental villi. On the other hand, a recent study demonstrated that placentas from preeclamptic patients showed a reduced Nrf2 activation associated with decreased HO-1 mRNA 32. These authors provided further evidence for the disruption of Nrf2 signaling, which failed to increase the antioxidative genes in the placenta. As a consequence, both mother and fetus may be affected by oxidative stress.

Genetic profiling of highly migratory EVT and villous cytotrophoblast revealed that lower HO-1 expression is associated with lower cell motility and trophoblast invasion 36. The invaded trophoblast of early onset IUGR and preeclampsia has been described as having impaired Nrf2 signaling compared to the control, as seen in immunohistochemistry 18. Collectively, so far there have been too few studies that have clarified the role of Nrf2 in pregnancy-related disorders. But although the findings have been mixed and the efficacy noted can be difficult to corroborate, the current few studies that have been able to draw any structured conclusions agree that the Nrf2 signaling is disturbed in placentas from patients with PE, indicating without a doubt the role of Nrf2 in the pathogenesis of PE.

Potential Therapeutic Effects of Nrf2 Inducers in PE

Heme oxygenase-1

HO-1 is an antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the oxidative degradation of heme into equimolar amounts of biliverdin, carbon monoxide (CO), and free iron (Fe+2) 37, 38. Biliverdin is then converted by biliverdin reductase into bilirubin. These two metabolites of heme breakdown, CO and bilirubin, have important functions that give HO-1 its vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, antioxidant, and cytoprotective properties 39. The promoter of the HO-1 gene contains consensus binding sites for multiple transcription factors including Nrf2, AP-1, AP-2, NFκB, HNF-1 and others, and one of the most crucial ones appears to be Nrf2 15.

It was shown that HO-1 induction or CO administration in HUVECs inhibits their release of sFlt-1 and sEng 40. Both of these antiangiogenic factors contribute to endothelial dysfunction in PE 8, 41, 42, 43, 44, suggesting that HO-1 exerts a proangiogenic phenotype. HO-1 is also able to offer protection against sFlt-1 while bypassing this effect 39, 40. In a sFlt-1-hypertensive rat model the activation of HO-1 reduced blood pressure 45. Moreover, the inhibition of HO-1 increased blood pressure in pregnant rats 45.

HO-1 induces VEGF in endothelial cells, keratinocytes, macrophages and tumor cells, and the delayed process of wound healing in HO-1 knockout mice confirmed the proangiogenic effects of HO-1 46. Studies of HO-1 knockout mice showed also that a partial deficiency in HO-1 is associated with morphological changes in the placenta and elevations in maternal diastolic blood pressure and plasma sFlt-1 levels 47. The expression of HO-1 can be induced by many compounds, some of which have therapeutic properties such as statins 48, probucol and probucol analogues 49, natural Nrf2 activators (kavalactones methysticin 50, sulforaphane 51, andrographolide 52), and others.

These findings may justify the hypothesis that pharmacological interventions to increase the activity of HO-1 in the placenta are useful options to treat PE by restoring disturbed maternal cardiovascular functions.

Unfortunately, statins have been identified as teratogenic and the risks associated with probucol are not well studied. Natural Nrf2 inducers may therefore be a promising future option to treat mothers with PE.

Hypotensive Effects of Nrf2 Activation

Two randomized placebo-controlled trials enrolling nulliparous women investigated the effects of antioxidant vitamin supplementation on the development of PE. Supplementation with vitamin C and E was found to have no significant effect on the risk of developing PE, while more low birthweight babies were born to women who took the high-dose antioxidants 53, 54. Elsen et al. (2012) reported a significant difference in the levels of the antioxidative vitamins E and A between patients with severe PE and those with a mild form of the disease 55, suggesting that dietary supplementation of the antioxidants may not be as helpful as the endogenous induction of these enzymes and that this effect can be achieved through the activation of Nrf2.

Several Nrf2 downstream target genes, including NADPH oxidase, superoxide dismutase, thioredoxin and HO-1, have been shown to protect against hypertension associated with different disorders 45, 56. In an animal model of deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt-induced hypertension, activation of Nrf2 via epicatechin prevented both an increase in systolic blood pressure and proteinuria induced by DOCA-salt treatment 57. Interestingly, a randomized clinical trial of the effect of bardoxolone methyl, an agent that protects cells from radiation-induced damage through Nrf2-dependent pathways 58, in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus showed that treatment with this agent improved renal function with blood pressure remaining constant in these patients 59. Furthermore, in a recent study by Vanhees et al. (2013) the authors showed that in utero exposure to flavonoids, Nrf2 inducers, not only attenuated DNA damage induced by oxidative stress in the liver of mice embryos but also had long-lasting effects and triggered the antioxidant system in adult mice 60. These are still new perspectives for the rational design and development of a novel class of Nrf2 activators to treat pregnancy-related disorders, and this will need much more investigation.

Conclusion

The role of Nrf2 in pregnancy complications is a new finding in research. It has become obvious that Nrf2 plays a key role in many pathways such as trophoblast invasion, preserving endothelial function and restoring the balance between pro- and antiangiogenic factors. Clinical trials with antioxidant interventions in preeclampsia have not proved successful. Based on the current literature, enhancement of the endogenous protection system against oxidative stress by Nrf2 activation seems to be a promising alternative. Thus, supplementation with Nrf2 inducers in a therapeutic design could be an innovative target which deserves further intensive research in well-conducted studies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

References

- 1.Steegers E A, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot J J. et al. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2010;376:631–644. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G. et al. Saving Mothersʼ Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG. 2011;118 01:1–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACOG . ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown M C, Best K E, Pearce M S. et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schausberger C E, Jacobs V R, Bogner G. et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy – a life-long risk? Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2013;73:47–52. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1328172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Rijn B B, Nijdam M E, Bruinse H W. et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:1040–1048. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31828ea3b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlembach D. Pre-eclampsia–still a disease of theories. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2003;49:69–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tallarek A-C, Huppertz B, Stepan H. Preeclampsia – aetiology, current diagnostics and clinical management, new therapy options and future perspectives. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2012;72:1107–1116. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1328080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redman C W, Sargent I L. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science. 2005;308:1592–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.1111726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufmann P, Black S, Huppertz B. Endovascular trophoblast invasion: implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray A J. Oxygen delivery and fetal-placental growth: beyond a question of supply and demand? Placenta. 2012;33 02:e16–e22. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanderlelie J, Venardos K, Clifton V L. et al. Increased biological oxidation and reduced anti-oxidant enzyme activity in pre-eclamptic placentae. Placenta. 2005;26:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaspar J W, Niture S K, Jaiswal A K. Nrf2:INrf2 (Keap1) signaling in oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1304–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wruck C J, Streetz K, Pavic G. et al. Nrf2 induces interleukin-6 (IL-6) expression via an antioxidant response element within the IL-6 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:4493–4499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kensler T W, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:89–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wruck C J, Huppertz B, Bose P. et al. Role of a fetal defence mechanism against oxidative stress in the aetiology of preeclampsia. Histopathology. 2009;55:102–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kweider N, Fragoulis A, Rosen C. et al. Interplay between vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 (Nrf2): implications for preeclampsia. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42863–42872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.286880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kweider N, Huppertz B, Wruck C J. et al. A role for Nrf2 in redox signalling of the invasive extravillous trophoblast in severe early onset IUGR associated with preeclampsia. PloS One. 2012;7:e47055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belo L, Caslake M, Santos-Silva A. et al. LDL size, total antioxidant status and oxidised LDL in normal human pregnancy: a longitudinal study. Atherosclerosis. 2004;177:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redman C W. Preeclampsia: a multi-stress disorder. Rev Med Interne. 2011;32 01:S41–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2011.03.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burton G J, Jauniaux E. Oxidative stress. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts J M, Taylor R N, Musci T J. et al. Preeclampsia: an endothelial cell disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:1200–1204. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huppertz B Abe E Murthi P et al. Placental angiogenesis, maternal and fetal vessels – a workshop report Placenta 200728(Suppl. A)S94–S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadyrov M, Kingdom J C, Huppertz B. Divergent trophoblast invasion and apoptosis in placental bed spiral arteries from pregnancies complicated by maternal anemia and early-onset preeclampsia/intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miranda Guisado M L, Vallejo-Vaz A J, Garcia Junco P S. et al. Abnormal levels of antioxidant defenses in a large sample of patients with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:274–278. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stepan H, Heihoff-Klose A, Faber R. Reduced antioxidant capacity in second-trimester pregnancies with pathological uterine perfusion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:579–583. doi: 10.1002/uog.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts J M, Hubel C A. Is oxidative stress the link in the two-stage model of pre-eclampsia? Lancet. 1999;354:788–789. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hung T H, Skepper J N, Burton G J. In vitro ischemia-reperfusion injury in term human placenta as a model for oxidative stress in pathological pregnancies. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1031–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61778-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taguchi K, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Molecular mechanisms of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway in stress response and cancer evolution. Genes Cells. 2011;16:123–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J M, Li J, Johnson D A. et al. Nrf2, a multi-organ protector? FASEB J. 2005;19:1061–1066. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2591hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandenburg L O, Kipp M, Lucius R. et al. Sulforaphane suppresses LPS-induced inflammation in primary rat microglia. Inflamm Res. 2010;59:443–450. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chigusa Y, Tatsumi K, Kondoh E. et al. Decreased lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX-1) and low Nrf2 activation in placenta are involved in preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1862–E1870. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mann G E, Niehueser-Saran J, Watson A. et al. Nrf2/ARE regulated antioxidant gene expression in endothelial and smooth muscle cells in oxidative stress: implications for atherosclerosis and preeclampsia. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2007;59:117–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valcarcel-Ares M N, Gautam T, Warrington J P. et al. Disruption of Nrf2 signaling impairs angiogenic capacity of endothelial cells: implications for microvascular aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:821–829. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loset M, Mundal S B, Johnson M P. et al. A transcriptional profile of the decidua in preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:8.4E82–8.4E28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bilban M, Haslinger P, Prast J. et al. Identification of novel trophoblast invasion-related genes: heme oxygenase-1 controls motility via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1000–1013. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbagallo I, Galvano F, Frigiola A. et al. Potential therapeutic effects of natural heme oxygenase-1 inducers in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:507–521. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tenhunen R, Marver H S, Schmid R. The enzymatic conversion of heme to bilirubin by microsomal heme oxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1968;61:748–755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levytska K, Kingdom J, Baczyk D. et al. Heme oxygenase-1 in placental development and pathology. Placenta. 2013;34:291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cudmore M, Ahmad S, Al-Ani B. et al. Negative regulation of soluble Flt-1 and soluble endoglin release by heme oxygenase-1. Circulation. 2007;115:1789–1797. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.660134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verlohren S, Herraiz I, Lapaire O. et al. The sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in different types of hypertensive pregnancy disorders and its prognostic potential in preeclamptic patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:5.8E52–5.8E59. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stepan H, Ebert T, Schrey S. et al. Serum levels of angiopoietin-related growth factor are increased in preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:314–318. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stepan H. Angiogenic factors and pre-eclampsia: an early marker is needed. Clin Sci. 2009;116:231–232. doi: 10.1042/CS20080598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fasshauer M, Waldeyer T, Seeger J. et al. Circulating high-molecular-weight adiponectin is upregulated in preeclampsia and is related to insulin sensitivity and renal function. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:197–201. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.George E M, Hosick P A, Stec D E. et al. Heme oxygenase inhibition increases blood pressure in pregnant rats. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:924–930. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpt045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grochot-Przeczek A, Dulak J, Jozkowicz A. Heme oxygenase-1 in neovascularisation: a diabetic perspective. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104:424–431. doi: 10.1160/TH09-12-0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao H, Wong R J, Kalish F S. et al. Effect of heme oxygenase-1 deficiency on placental development. Placenta. 2009;30:861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grosser N, Hemmerle A, Berndt G. et al. The antioxidant defense protein heme oxygenase 1 is a novel target for statins in endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:2064–2071. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deng Y M, Wu B J, Witting P K. et al. Probucol protects against smooth muscle cell proliferation by upregulating heme oxygenase-1. Circulation. 2004;110:1855–1860. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142610.10530.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wruck C J, Gotz M E, Herdegen T. et al. Kavalactones protect neural cells against amyloid beta peptide-induced neurotoxicity via extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2-dependent nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1785–1795. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu L, Juurlink B H. The impaired glutathione system and its up-regulation by sulforaphane in vascular smooth muscle cells from spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1819–1825. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200110000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guan S P, Tee W, Ng D S. et al. Andrographolide protects against cigarette smoke-induced oxidative lung injury via augmentation of Nrf2 activity. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:1707–1718. doi: 10.1111/bph.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poston L, Briley A L, Seed P T. et al. Vitamin C and vitamin E in pregnant women at risk for pre-eclampsia (VIP trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1145–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68433-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rumbold A R, Crowther C A, Haslam R R. et al. Vitamins C and E and the risks of preeclampsia and perinatal complications. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1796–1806. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elsen C, Rivas-Echeverría C, Sahland K. et al. Vitamins E, A and B2 as possible risk factors for preeclampsia – under consideration of the PROPER study (“Prevention of preeclampsia by high-dose riboflavin supplementation”) Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2012;72:846–852. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voelkel N F, Bogaard H J, Al Husseini A. et al. Antioxidants for the treatment of patients with severe angioproliferative pulmonary hypertension? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:1810–1817. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gomez-Guzman M, Jimenez R, Sanchez M. et al. Epicatechin lowers blood pressure, restores endothelial function, and decreases oxidative stress and endothelin-1 and NADPH oxidase activity in DOCA-salt hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim S B, Eskiocak U, Ly P. Bardoxolone-methyl (CDDO-Me): an antioxidant, antiinflammatory modulator is a novel radiation countermeasure and mitigator. In: Proceedings of the 22nd Annual NASA Space Radiation Investigatorsʼ Workshop 2011; Sep 2011

- 59.Rojas-Rivera J, Ortiz A, Egido J. Antioxidants in kidney diseases: the impact of bardoxolone methyl. Int J Nephrol. 2012;2012:321714. doi: 10.1155/2012/321714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vanhees K, van Schooten F J, van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani S B. et al. Intrauterine exposure to flavonoids modifies antioxidant status at adulthood and decreases oxidative stress-induced DNA damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;57:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]