I have read with interest the recent paper by Liu and Zhang 1 on the putative association of the PRSS1 gene with pancreatitis. In their article, the authors claim a highly significant association based on a meta-analysis of seven previous case-control studies. Their methodological approach, however, warrants a cautionary comment.

To assess the impact of PRSS1 mutations, the authors have conceptualized the entire gene as a risk-modifier. Thus instead of counting carriers of a single variant, all carriers of at least one variant were supposedly grouped together. Clearly, a metaanalysis in this fashion is quite uninformative. A gene is made up of numerous DNA base pairs of which some may augment the risk for disease, while others may act in the opposite direction and yet others act neutrally with regard to a given phenotype. Similar risk-enhancing effects of genetic variants within the same gene imply that linkage disequilibrium between these markers is very high. This does not apply to PRSS1 mutations and therefore no rationale exists for indiscriminate pooling of mutations or polymorphisms (i.e. N29I, N29T, L104P, R116C, A121T, R122H, R122C, T137M, C139S, D162D, G208A) across the gene.

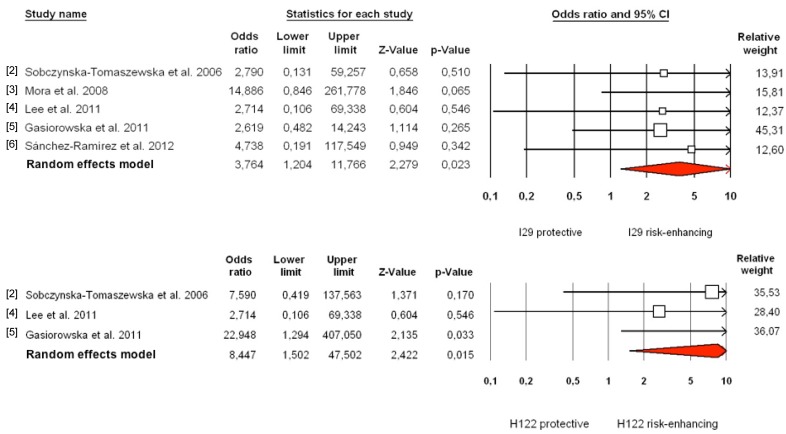

When data are re-analyzed for the two most commonly examined mutations (N29I and R122H) assuming a dominant mode of inheritance for the minor allele under a random effects model, and applying a Bonferroni correction, the overall net effect remains significant for R122H (pcorrected = .03) but is only borderline significant for N29I (pcorrected = .05, Fig. 1). When the same analysis is restricted to European populations, significance is lost for N29I (pcorrected > .09). Moreover, the true effect of PRSS1 variants is likely obscured by pooling of all age-groups, pooling of acute and chronic phenotypes, pooling of early and late onset phenotypes, plus pooling of primary and secondary forms of pancreatitis. Future analyses will need to reassess in more detail the association with PRSS1 for subjects with respect to high and low genetic load.

Fig 1.

Forest plots for metaanalyses of all studies addressing PRSS1 carrier status for N29I (top) and R122H (bottom).

References

- 1.Liu J, Zhang HX. A comprehensive study indicates PRSS1 gene is significantly associated with pancreatitis. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:981–7. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobczyńska-Tomaszewska A, Bak D, Oralewska B. et al. Analysis of CFTR, SPINK1, PRSS1 and AAT mutations in children with acute or chronic pancreatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:299–306. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000232570.48773.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mora J, Comas L, Ripoll E. et al. Genetic mutations in a Spanish population with chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2009;9:644–51. doi: 10.1159/000181177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YJ, Kim KM, Choi JH, Lee BH, Kim GH, Yoo HW. High incidence of PRSS1 and SPINK1 mutations in Korean children with acute recurrent and chronic pancreatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:478–81. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31820e2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasiorowska A, Talar-Wojnarowska R, Czupryniak L. et al. The prevalence of cationic trypsinogen (PRSS1) and serine protease inhibitor, Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) gene mutations in Polish patients with alcoholic and idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:894–901. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1349-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]