Abstract

Background

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) in youth is characterized by excessive worry across domains for ≥ six months, an inability to stop worrying, and at least one physiological symptom. The present study examined the multiple domains that optimally distinguish (1) GAD youth from non anxiety disordered youth and (2) GAD youth from other anxiety-disordered youth.

Methods

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses examined a sample of youth (N = 180) aged 7–13 (M = 10.10; 52% male) to determine optimal cut scores to distinguish GAD youth from (1) non anxiety-disordered youth and (2) other anxiety-disordered youth. The diagnostic efficiency of worries and physiological symptoms was also examined.

Results

By parent report, three worries and four physiological symptoms had favorable cut scores, and several specific worries possessed high diagnostic efficiency. Children endorsed fewer GAD symptoms.

Conclusions

Recommendations are made regarding the criteria for GAD in youth and interview sequencing of symptom queries.

Keywords: generalized anxiety disorder, GAD, anxiety disorders, children, classification, diagnostic criteria, DSM-V

Introduction

Overall prevalence of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) in children and adolescents in the community has been estimated at 2.4% to 10.8%.[1–3] In clinic-referred youth, the prevalence ranges from 2.8% to 15%.[4,5] GAD has been associated with poor academic achievement, social problems, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation.[6] If untreated, GAD in childhood (previously Overanxious Disorder; OAD) may be a precursor to comorbid anxiety and mood disorders.[7–9] Childhood anxiety disorders (e.g., GAD, Social Phobia [SP], and Separation Anxiety Disorder [SAD]) are highly comorbid with one another[10–13] and these high rates of comorbidity have led some to suggest these disorders may share an underlying anxiety construct.[1,14] While these high levels of comorbidity may reflect a meaningful association between underlying disorders, it may also reflect a problem with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) classification system.

Given the prevalence and impairment associated with GAD in youth, accurate diagnosis is critical, although multiple revisions and the changing focus of childhood GAD/OAD criteria across DSM iterations has hampered research. The diagnosis of GAD in youth is recent: OAD was eliminated in the fourth edition of the DSM (DSM-IV)[15] and the criteria for GAD in adults were extended downward. This decision was based on only sparse evidence though research does suggest that diagnostic differences between GAD and OAD in youth are nonsignificant.[16]

Across several DSM editions, GAD has evolved from a nonspecific residual anxiety category to a primary anxiety disorder characterized by excessive and uncontrollable worry and associated somatic complaints.[17] Investigators have begun examining the diagnostic utility of GAD symptoms in youth. Tracey and colleagues[18] examined the endorsement and predictive power of each of the physiological symptoms that comprise a GAD diagnosis in GAD youth, other anxiety-disordered youth, and non anxiety-disordered youth. They found that parent-reported irritability and youth-reported restlessness/being keyed up were predictive of youth receiving a GAD diagnosis. Muscle tension was infrequently endorsed. Although this study provides initial information, the specificity of these symptoms for diagnosis of GAD was not investigated.

Pina and colleagues[19] investigated the diagnostic value of the symptoms comprising the uncontrollable excessive worry criteria and physiological symptom criteria in youth with either diagnoses of GAD or OAD in their diagnostic profile (but not as a primary diagnosis). Pina and colleagues[19] reported that both child and parent endorsement of uncontrollable excessive worry in the area of “health of self” was highly specific or descriptive of GAD. Similarly, parent-reported uncontrollable excessive worry in the area of “health of others” had the highest diagnostic value. Regarding physiological symptoms, highest diagnostic value was associated with child-reported irritability and trouble sleeping; adolescent-reported trouble sitting still/relaxing and trouble concentrating; parent-reported trouble concentrating in children; and parent-reported trouble sitting still/relaxing and trouble sleeping in adolescents.

If the findings of Tracey et al.[18] and Pina et al.[19] are replicated this would provide support for a preferred sequence for inquiring about GAD symptoms.[20] Replication may suggest interviewers start by asking about symptoms with the highest predictive value, followed by symptoms with average prediction, and then symptoms with low predictive value. Additionally, both Tracey et al.[18] and Pina et al.[19] compared GAD youth with youth with other anxiety disorders and only Tracey and colleagues included a small sample of 18 non anxiety-disordered youth. Replication with large comparison groups of youth with other anxiety disorders as well as non-anxiety disordered youth may also offer suggestions for improving diagnostic accuracy by distinguishing specific diagnostic features of GAD from underlying features across the anxiety disorders.

To meet DSM-IV criteria for a diagnosis of GAD, youth must worry about an unspecified number of events or activities and experience at least one physiological symptom. Research has not yet examined the actual number of domains of worry and physiological symptoms which optimally distinguishes: (1) GAD youth from non anxiety-disordered youth, and (2) GAD youth from other anxiety-disordered youth (i.e., SAD and/or SP). The present study investigated the diagnostic utility of GAD symptoms using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Number of parent and youth reported worries and physiological symptoms were investigated to determine if optimal cut scores exist that distinguish (1) GAD youth from non anxiety-disordered youth and (2) GAD youth from other anxiety-disordered youth. At each potential cut score, we examined estimates of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive power, and negative predictive power. Additionally, conditional probability statistics and odds ratios (ORs) determined the diagnostic efficiency of specific worries and physiological symptoms.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 180) included treatment-seeking youth and non-referred community participants. Children (aged 7–13, M = 10.10; 53.9% male) were recruited as part of an Institutional Review Board approved randomized clinical trial (RCT; see the primary report[21] for more details) evaluating cognitive-behavioral treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Ethnicity was self-identified as: 87.6% Caucasian, 7.3% African American, 2.8%, Hispanic, and 2.2% other/mixed race.

Of the treatment seeking youth (n = 137), 84 met diagnostic criteria for GAD as the principal diagnosis and 53 met criteria for SAD or SP but not GAD. Of youth diagnosed with GAD, 37 (44%) met criteria for GAD according to both parent and child reports, 45 (54%) met by parent report only, and 2 (.02%) met by child report only. Nonreferred, non anxiety-disordered (NAD) community participants were a comparison group (n = 43). Analyses were conducted on data provided before treatment initiation.

Measures

Diagnoses were determined using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (ADIS-C/P),[22] a semi-structured interview administered separately to parents and children. Diagnosticians provided a Clinical Severity Rating (CSR) on a 9-point scale (0–8); ≥ 4 required for a diagnosis. The ADIS-C/P has favorable psychometric properties.[23–25] Diagnostic training followed recommended guidelines. Experienced diagnosticians were trainers: they observed practice administrations among trainees and with actual clients, provided feedback and supervision on the practice interviews, and conducted reliability assessments. Trainees were required to reach interrater reliability of 0.85 (Cohen’s Kappa) or above. Ongoing diagnostic reliability checks were conducted by the head diagnostic interviewer by examining randomly selected diagnostic interviews. A random reliability check during the study indicated that all diagnosticians maintained their initial reliability (i.e., kappa ≥ .85).

Procedure

Informed consent was obtained for participants after the nature of the procedures was explained. Diagnosticians interviewed children and parents separately and interviews were scored according to DSM-IV criteria using the ADIS-C/P.[22] The child and parents were interviewed by different diagnosticians, and diagnosticians determined diagnoses and CSR ratings independently (i.e., without knowledge of the other informant’s report). Based on their diagnostic profiles, treatment-seeking children were assigned to the GAD group or the SP/SAD group. Community volunteers without an anxiety disorder comprised the NAD group.

GAD was assigned if either the child or parent(s) endorse sufficient criteria including one or more areas of worry, at least one physiological symptom, and associated distress and/or interference for 6 months or more (in accordance with ADIS-C/P scoring procedures). The diagnostician discusses each of 9 domains of worry with the informant, and the informant assigns a global interference rating (GIR; ranging from 0 to 8) to indicate the extent of the worry. These worry domains include: school, performance, social/interpersonal, little things, perfectionism, health of the child, health of a significant other, family, and world affairs. Additionally, difficulty to control the worry (yes/no) is queried. The informant also responds yes/no for six physiological symptoms that frequently accompany worry. Endorsement of a worry was operationalized as the assignment of a GIR of ≥ 4. Endorsement of a physiological symptom was operationalized as the response of “yes” to experiencing the symptom while worrying.

Data Analyses

At each potential cut score (i.e., number of worry domains endorsed with a GIR rating of ≥ 4; presence or absence of physiological symptoms), sensitivity was operationalized as percentage of youth meeting diagnostic criteria for GAD who were correctly identified as having GAD. Specificity at each potential cut score was defined as the percentage of youth not meeting diagnostic criteria for GAD who were correctly classified as not having GAD. Matthey and Petrovski[26] suggest that a worthwhile diagnostic cut point is one for which sensitivity ≥ .70 and specificity ≥ .80.

ROC analyses examined the diagnostic utility of the quantity of worries and physiological symptoms to distinguish GAD youth from NAD youth and SAD/SP youth. Sensitivities and specificities at each cut score were plotted, yielding a curve. The area under the curve (AUC) ranges from 1.0 (perfect partition of test scores of the two groups) to 0.5 (no distributional differences between the two groups of test scores evident). The AUC provides a quantitative estimate of diagnostic utility (accuracy) of the number of worries.[27] Positive predictive power (PPP) was determined by calculating percentage of youth classified at each cut score as having GAD when they did in fact have GAD. Four estimates of PPP were computed for each cut score: one PPP estimate for each of the four potential combinations of comparison group (i.e., NAD or SAD/SP) and informant data (i.e., parent or child report). Negative predictive power (NPP) was determined by calculating percentage of youth classified at each cut score as non-GAD when they did in fact not meet criteria for GAD. Four estimates of NPP were computed for each cut score: one NPP estimate for each of the four potential combinations of comparison group and informant data. PPP and NPP statistics were corrected for chance agreement (i.e., cPPP and cNPP)[28] for all analyses.

Results

Groups (i.e., GAD, NAD, SAD/SP) did not differ significantly with regard to race, gender, or child age (all ps > .05). Groups differed in the number of worry domains endorsed by parent report, F (2, 168) = 96.82, p < .0001, though they did not differ in the number of worry domains endorsed by child report, F (2, 164) = 2.68, p = .072. Tukey’s honestly significant difference tests indicated that GAD youth endorsed a greater number of worry domains than did NAD and SAD/SP youth, according to parent report (all ps < .01, after Bonferroni corrections). According to parent report, the mean number of endorsed worry domains for the GAD, SAD/SP, and NAD groups was 4.27 (SD = 2.10), 1.15 (SD = 1.46), and .27 (SD = .55) respectively. According to child report, the mean number of endorsed worry domains for the GAD, SAD/SP, and NAD groups was 2.31 (SD = 2.49), 1.14 (SD = 2.14), and 1.34 (SD = 1.96) respectively. SAD/SP youth did not differ from NAD youth in number of parent- or child-reported worries.

Regarding physiological symptoms, groups differed in the number of symptoms endorsed by parent report, F (2, 115) = 27.31, p < .0001. Groups did not differ in the number of physiological symptoms endorsed by child report, F (2, 92) = 1.22, p = .301. Tukey’s honestly significant difference tests indicated that GAD youth endorsed a greater number of physiological symptoms than NAD and SAD/SP youth, according to parent report (all ps < .01, after Bonferroni corrections). According to parent report, the mean number of endorsed physiological symptoms for the GAD, SAD/SP, and NAD groups were 4.23 (SD = 1.18), 3.24 (SD = 1.36), and 1.46 (SD = 1.29) respectively. According to child report, the mean number of physiological symptoms endorsed for GAD, SAD/SP, and NAD groups were 3.57 (SD = 1.55), 3.00 (SD = 2.05), and 2.84 (SD = 1.61) respectively. SAD/SP youth also differed significantly from NAD youth in number of parent-endorsed physiological symptoms. Tukey’s honestly significant difference tests indicated that SAD/SP youth endorsed a greater number of physiological symptoms than did NAD youth, according to parent report (p < .01, after Bonferroni correction). SAD/SP youth did not differ from NAD youth in number of child-endorsed physiological symptoms.

Diagnostic Utility of Youth Worry

ROC analyses examined the diagnostic utility of the quantity of worries to distinguish GAD youth from NAD youth and SAD/SP youth using the procedures outlined above.

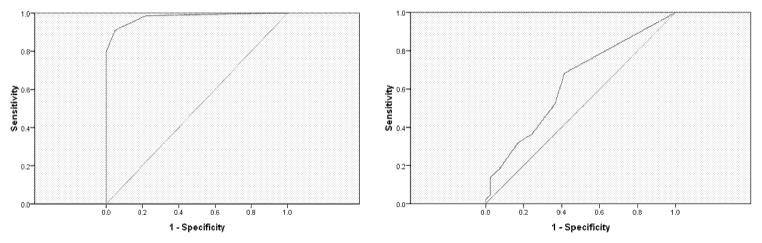

Figure 1 presents the ROC curves generated by plotting sensitivities by 1-specificities at each potential cut point (i.e., number of worries), when comparing GAD and NAD youth for parent and child report data, respectively. When compared with NAD youth, number of worries demonstrated excellent overall utility in distinguishing true positives from true negatives for parent report (AUC = .98) and poor utility for child report (AUC = .63).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plot of sensitivities and 1-specificities for each cut score based on total number of parent-reported (top) and child-reported (bottom) worries, as compared with non anxiety-disordered (NAD) youth. The diagonal line intersecting at (0,0) represents the null hypothesis (i.e., number of reported worries does not distinguish the groups). AUC = area under the curve.

Parent AUC = .98; Child AUC = .63

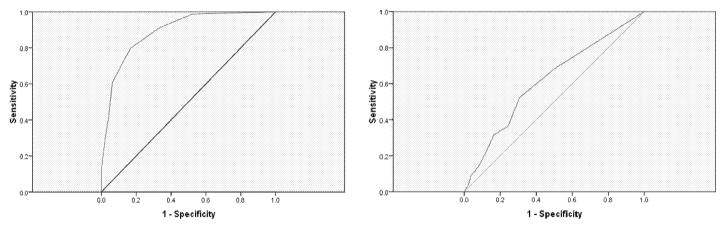

Figure 2 presents the ROC curves when comparing GAD and SAD/SP youth for parent and child report data, respectively. When compared with SAD/SP youth, number of worries demonstrated good overall utility for parent report (AUC = .89) and poor overall utility for child report (AUC = .62).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plot of sensitivities and 1-specificities for each cut score based on total number of parent-reported (top) and child-reported (bottom) worries, as compared with youth with other anxiety disorders (SAD/SP). The diagonal line intersecting at (0,0) represents the null hypothesis (i.e., number of reported worries does not distinguish the groups). AUC = area under the curve.

Parent AUC = .89; Child AUC = .62

For parent report, an optimal cut score of 3 worries was identified as meeting the .70/.80 sensitivity/specificity criterion across both sets of parent analyses. In both sets of child analyses, no optimal cut score could be identified. See Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Diagnostic utility of the number of parent- and child-reported worry domains (NAD as comparison group).

| No. of reported worry domains | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPP | cPPP | NPP | cNPP | Base rate | κ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-reported worries | ||||||||

| 9 | .05 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .35 | .02 | .03 | .04 |

| 8 | .08 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .36 | .03 | .05 | .05 |

| 7 | .13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .37 | .05 | .08 | .09 |

| 6 | .29 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .42 | .12 | .19 | .22 |

| 5 | .42 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .47 | .20 | .28 | .33 |

| 4 | .61 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .57 | .35 | .40 | .51 |

| 3 | .80 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .72 | .57 | .53 | .73 |

| 2 | .91 | .78 | .97 | .92 | .85 | .77 | .62 | .84 |

| 1 | .99 | .95 | .90 | .70 | .97 | .95 | .73 | .81 |

|

| ||||||||

| Child-reported worries | ||||||||

| 9 | .02 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .49 | .01 | .01 | .02 |

| 8 | .05 | .98 | .67 | .31 | .49 | .01 | .04 | .02 |

| 7 | .09 | .98 | .80 | .59 | .50 | .03 | .06 | .06 |

| 6 | .14 | .98 | .86 | .70 | .51 | .06 | .08 | .11 |

| 5 | .18 | .93 | .73 | .43 | .51 | .06 | .13 | .11 |

| 4 | .32 | .83 | .67 | .31 | .53 | .09 | .25 | .15 |

| 3 | .36 | .76 | .62 | .20 | .53 | .08 | .31 | .12 |

| 2 | .52 | .63 | .61 | .18 | .55 | .14 | .45 | .16 |

| 1 | .68 | .59 | .64 | .25 | .63 | .29 | .55 | .27 |

Note. NAD = non anxiety-disordered youth; PPP = positive predictive power; NPP = negative predictive power; c = corrected; base rate = percentage scoring at or above cut score; κ = agreement between classification and Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents after correcting for chance.

Table 2.

Diagnostic utility of the number of parent- and child-reported worry domains (SAD/SP as comparison group).

| No. of reported worry domains | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPP | cPPP | NPP | cNPP | Base rate | κ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-reported worries | ||||||||

| 9 | .05 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .39 | .02 | .03 | .04 |

| 8 | .08 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .40 | .03 | .05 | .06 |

| 7 | .13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .41 | .05 | .08 | .10 |

| 6 | .29 | .98 | .96 | .89 | .46 | .13 | .19 | .22 |

| 5 | .42 | .96 | .94 | .85 | .50 | .20 | .28 | .32 |

| 4 | .61 | .94 | .94 | .84 | .59 | .34 | .40 | .49 |

| 3 | .80 | .83 | .89 | .70 | .71 | .54 | .56 | .61 |

| 2 | .91 | .67 | .82 | .52 | .82 | .71 | .69 | .60 |

| 1 | .99 | .48 | .76 | .36 | .96 | .93 | .81 | .51 |

|

| ||||||||

| Child-reported worries | ||||||||

| 9 | .02 | .99 | .50 | .22 | .64 | .01 | .02 | .01 |

| 8 | .05 | .98 | .50 | .22 | .64 | .01 | .03 | .03 |

| 7 | .09 | .96 | .57 | .33 | .65 | .04 | .06 | .06 |

| 6 | .14 | .92 | .50 | .22 | .65 | .04 | .10 | .07 |

| 5 | .18 | .90 | .50 | .22 | .66 | .06 | .13 | .09 |

| 4 | .32 | .83 | .52 | .25 | .68 | .12 | .22 | .17 |

| 3 | .36 | .76 | .46 | .15 | .68 | .12 | .29 | .13 |

| 2 | .52 | .69 | .49 | .20 | .72 | .22 | .39 | .21 |

| 1 | .68 | .50 | .43 | .12 | .74 | .27 | .57 | .16 |

Note. SAD/SP = youth with other anxiety disorders; PPP = positive predictive power; NPP = negative predictive power; c = corrected; base rate = percentage scoring at or above cut score; κ = agreement between classification and Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents after correcting for chance.

Diagnostic Utility of Physiological Symptoms

ROC analyses were also conducted to examine the diagnostic utility of the quantity of physiological symptoms to distinguish GAD youth from NAD youth and SAD/SP youth.

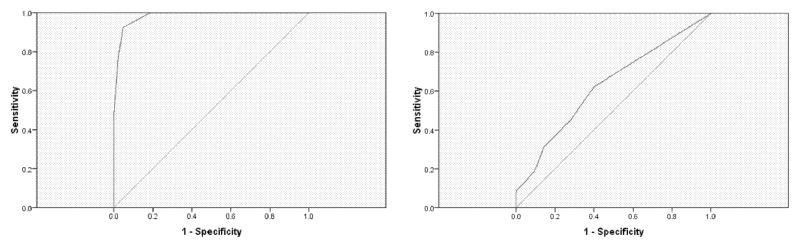

Figure 3 presents the ROC curves generated at each potential cut point when comparing GAD and NAD youth for parent and child report data, respectively. When compared with NAD youth, number of physiological symptoms demonstrated excellent overall utility in distinguishing true positives from true negatives for parent report (AUC = .98) and poor utility for child report (AUC = .63).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plot of sensitivities and 1-specificities for each cut score based on total number of parent-reported (top) and child-reported (bottom) physiological symptoms, as compared with non anxiety-disordered (NAD) youth. The diagonal line intersecting at (0,0) represents the null hypothesis (i.e., number of reported symptoms does not distinguish the groups). AUC = area under the curve.

Parent AUC = .98; Child AUC = .63

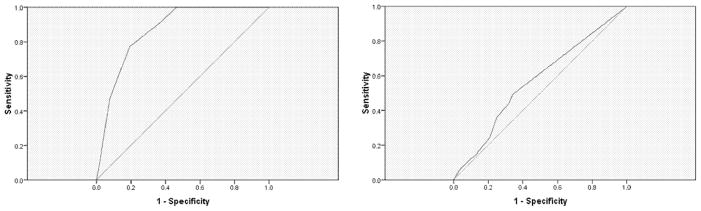

Figure 4 presents the ROC curves when comparing GAD and SAD/SP youth for parent and child report data, respectively. When compared with SAD/SP youth, number of physiological symptoms demonstrated good overall utility for parent report (AUC = .87) and poor utility for child report (AUC = .57).

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plot of sensitivities and 1-specificities for each cut score based on total number of parent-reported (top) and child-reported (bottom) physiological symptoms, as compared with youth with other anxiety disorders (SAD/SP). The diagonal line intersecting at (0,0) represents the null hypothesis (i.e., number of reported symptoms does not distinguish the groups). AUC = area under the curve.

Parent AUC = .87; Child AUC = .57

For parent report of GAD physiological symptoms, an optimal cut score of 4 physiological symptoms was identified when comparing GAD youth with SAD/SP youth. Several cut scores achieved the desired sensitivity/specificity criteria when comparing GAD youth with NAD youth. When compared with NAD youth, cut scores of 2 to 4 met the .70/.80 sensitivity/specificity criterion, with a cut score of 4 demonstrating the greatest concordance based on quantity of physiological symptoms and GAD diagnosis (see Table 3). In both sets of child analyses, no optimal cut score could be identified. See Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Diagnostic utility of the number of parent- and child-reported physiological symptoms (NAD as comparison group).

| No. of reported physiological symptoms | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPP | cPPP | NPP | cNPP | Base rate | κ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-reported symptoms | ||||||||

| 6 | .10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .42 | .04 | .06 | .07 |

| 5 | .47 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .51 | .24 | .30 | .38 |

| 4 | .77 | .98 | .98 | .95 | .70 | .54 | .51 | .68 |

| 3 | .94 | .95 | .97 | .92 | .87 | .80 | .61 | .86 |

| 2 | .96 | .88 | .94 | .82 | .93 | .89 | .66 | .86 |

| 1 | 1 | .81 | .91 | .74 | 1 | 1 | .71 | .85 |

|

| ||||||||

| Child-reported symptoms | ||||||||

| 6 | .08 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .49 | .04 | .04 | .08 |

| 5 | .19 | .90 | .69 | .34 | .49 | .05 | .14 | .09 |

| 4 | .31 | .86 | .71 | .39 | .52 | .10 | .23 | .16 |

| 3 | .46 | .71 | .65 | .24 | .54 | .13 | .38 | .17 |

| 2 | .56 | .64 | .64 | .23 | .56 | .18 | .47 | .21 |

| 1 | .63 | .60 | .64 | .22 | .58 | .22 | .52 | .22 |

Note. NAD = non anxiety-disordered youth; PPP = positive predictive power; NPP = negative predictive power; c = corrected; base rate = percentage scoring at or above cut score; κ = agreement between classification and Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents after correcting for chance.

Table 4.

Diagnostic utility of the number of parent- and child-reported physiological symptoms (SAD/SP as comparison group).

| No. of reported physiological symptoms | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPP | cPPP | NPP | cNPP | Base rate | κ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-reported symptoms | ||||||||

| 6 | .10 | .98 | .89 | .72 | .42 | .03 | .07 | .07 |

| 5 | .47 | .92 | .90 | .75 | .53 | .23 | .31 | .35 |

| 4 | .77 | .81 | .86 | .65 | .70 | .50 | .54 | .57 |

| 3 | .92 | .62 | .78 | .46 | .84 | .74 | .71 | .57 |

| 2 | .96 | .58 | .78 | .43 | .91 | .85 | .75 | .58 |

| 1 | 1 | .54 | .77 | .41 | 1 | 1 | .78 | .59 |

|

| ||||||||

| Child-reported symptoms | ||||||||

| 6 | .07 | .96 | .50 | .20 | .63 | .02 | .05 | .03 |

| 5 | .15 | .87 | .41 | .05 | .63 | .01 | .14 | .02 |

| 4 | .25 | .79 | .42 | .06 | .63 | .03 | .22 | .04 |

| 3 | .36 | .75 | .47 | .14 | .66 | .10 | .29 | .12 |

| 2 | .44 | .68 | .46 | .13 | .67 | .12 | .37 | .12 |

| 1 | .49 | .66 | .47 | .14 | .68 | .16 | .40 | .15 |

Note. SAD/SP = youth with other anxiety disorders; PPP = positive predictive power; NPP = negative predictive power; c = corrected; base rate = percentage scoring at or above cut score; κ = agreement between classification and Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents after correcting for chance.

Diagnostic Efficiency of Worries

Nine separate worries were examined for their ability to distinguish GAD youth from both NAD and SAD/SP youth. Conditional probability statistics were computed, consistent with existing literature.[28,29] Odds ratios (OR) reflect the likelihood of diagnosis given the presence of a symptom and cPPP indicates the proportion of youth endorsing a given worry who actually meet diagnostic criteria for GAD. OR and cPPP are most informative for determining an item’s diagnostic efficiency.[30] Sensitivity, specificity, and cNPP estimates were also computed. See Table 5.

Table 5.

Corrected positive predictive power and odds ratio indices.

| Comparison of GAD and NAD youth | Comparison of GAD and SAD/SP youth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent report | Child report | Parent report | Child report | |||||

| Worry | cPPP | ORa | cPPP | OR | cPPP | OR | cPPP | OR |

| School worry (e.g., starting school, grades, homework) | .90 | 47.2* | .17 | 1.84 | .68 | 12.39 | .75 | 9.09* |

| Performance worry (e.g., being good enough in sports, art) | .77 | 13.03* | .27 | 2.25 | .55 | 5.62 | .06 | 1.15 |

| Social or Interpersonal worry (e.g., impressions, appearance) | .92 | 35.45* | .15 | 1.62 | .34 | 2.59 | .17 | 1.49 |

| Little things (e.g., things that happened in the past) | 1 | - | .42 | 3.56 | .78 | 10.24* | .51 | 3.51 |

| Perfectionism worry (e.g., being on time, keeping schedules) | .92 | 34.62* | .08 | 1.28 | .66 | 6.47 | .22 | 1.62 |

| Health (child) worry | 1 | - | .13 | 1.60 | .70 | 6.79* | .22 | 1.75 |

| Health (significant other) worry | .82 | 11.92* | .16 | 1.79 | .84 | 14.61* | .09 | 1.29 |

| Family worry (e.g., divorce, finances) | .92 | 34.62* | .09 | 1.37 | .60 | 5.43 | .14 | 1.41 |

| World affairs (e.g., war, crime) | 1 | - | .18 | 1.88 | .82 | 15.19* | .32 | 2.28 |

| M | .92 | 29.48 | .28 | 2.62 | .66 | 8.82 | .18 | 1.91 |

| SD | .08 | 14.01 | .22 | 2.62 | .15 | 4.46 | .10 | .68 |

Note. GAD = youth meeting criteria for generalized anxiety disorder; NAD = non anxiety-disordered youth; SAD/SP = youth with other anxiety disorders; cPPP = corrected positive predictive power; OR = odds ratio.

Dashes in this column indicate OR is incomputable when specificity = 1.

OR is significant at p < .05 and cPPP > .70.

In the comparison of GAD and NAD youth, parent-reported worries demonstrated generally high OR values (mean OR = 29.48) and good cPPP estimates (mean cPPP = .92) and the following worries possessed high diagnostic efficiency: school, performance, social/interpersonal, perfectionism, health of a significant other, and family. In the comparison of GAD and SAD/SP youth, parent-reported worries achieved a mean OR value of 8.82 and a mean cPPP estimate of .66 and the following worries possessed high diagnostic efficiency: little things, health (of both the child and of a significant other), and world affairs. The only worry possessing high diagnostic efficiency in both comparisons was health of a significant other (see Table 5).

In the comparison of GAD and NAD youth, child-reported worries demonstrated markedly lower OR values (mean OR = 2.62) and cPPP estimates (mean cPPP = .28) and no worries possessed high diagnostic efficiency. In the comparison of GAD and SAD/SP youth, child-reported worries again generally achieved low OR values (mean OR = 1.91) and cPPP estimates (mean cPPP = .18) and one worry possessed high diagnostic efficiency: school worry (see Table 5).

Diagnostic Efficiency of Physiological Symptoms

Six separate physiological symptoms were examined for their ability to distinguish GAD youth from NAD and SAD/SP youth.

In the comparison of GAD and NAD youth, parent-reported physiological symptoms demonstrated generally high OR values (mean OR = 73.92) and good cPPP estimates (mean cPPP = .89) and all six physiological symptoms possessed high diagnostic efficiency: unable to sit still/relax, tires easily, difficulty paying attention/concentrating, easily upset/irritable, muscle aches, and difficulty sleeping. In the comparison of GAD and SAD/SP youth, parent-reported physiological symptoms achieved a mean OR of 12.27 and a mean cPPP estimate of .52 and no physiological symptoms possessed high diagnostic efficiency. See Table 6.

Table 6.

Corrected positive predictive power and odds ratio indices.

| Comparison of GAD and NAD youth | Comparison of GAD and SAD/SP youth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent report | Child report | Parent report | Child report | |||||

| Physiological Symptom | cPPP | OR | cPPP | OR | cPPP | OR | cPPP | OR |

| Unable to sit still/relax | .83 | 30.71* | .23 | 1.96 | .53 | 8.76 | .17 | 1.90 |

| Tires easily | .89 | 19.50* | .43 | 3.33 | .52 | 3.56 | .25 | 2.27 |

| Difficulty paying attention/concentrating | .92 | 99.57* | .15 | 1.50 | .44 | 8.44 | .05 | 1.20 |

| Easily upset/irritable | .80 | 164.44* | .39 | 2.90 | .42 | 33.62 | .15 | 1.64 |

| Muscle aches | .94 | 56.40* | .11 | 1.28 | .63 | 7.39 | .00 | 1.01 |

| Difficulty sleeping | .91 | 72.89* | .28 | 2.21 | .59 | 11.85 | .10 | 1.43 |

| M | .89 | 73.92 | .26 | 2.20 | .52 | 12.27 | .12 | 1.57 |

| SD | .06 | 52.89 | .13 | .80 | .08 | 10.80 | .09 | .46 |

Note. GAD = youth meeting criteria for generalized anxiety disorder; NAD = non anxiety-disordered youth; SAD/SP = youth with other anxiety disorders; cPPP = corrected positive predictive power; OR = odds ratio.

OR is significant at p < .05 and cPPP > .70.

In the comparison of GAD and NAD youth, child-reported physiological symptoms demonstrated markedly lower OR values (mean OR = 2.20) and cPPP estimates (mean cPPP = .26) and no physiological symptoms possessed high diagnostic efficiency. In the comparison of GAD and SAD/SP youth, child-reported physiological symptoms again generally achieved low OR values (mean OR = 1.57) and cPPP estimates (mean cPPP = .12) and again no physiological symptoms possessed high diagnostic efficiency. See Table 6.

Discussion

The present analyses examined the diagnostic efficiency of worries when comparing GAD youth to NAD and SAD/SP youth. By parent report, three worry areas represent the most favorable cut score to distinguish GAD youth from NAD and SAD/SP youth. Additionally, most of the worry areas queried in the ADIS-C/P possessed high diagnostic efficiency (i.e., school, performance, social/interpersonal, perfectionism, health of a significant other, family) when distinguishing GAD from NAD youth. When distinguishing GAD from SAD/SP youth, the following worry areas possessed high diagnostic efficiency: little things, health of the child, health of a significant other, world affairs. Health of a significant other distinguished across groups. According to child report, no favorable cut score distinguished GAD youth across comparisons. Only one child-reported worry area (school) possessed high diagnostic efficiency.

The present analyses also examined the overall diagnostic efficiency of physiological symptoms. By parent report, four physiological symptoms represent the most favorable cut score to distinguish GAD from NAD youth. Additionally, all physiological symptoms areas queried possessed high diagnostic efficiency (i.e., unable to sit still/relax, tires easily, difficulty paying attention/concentrating, easily upset/irritable, muscle aches, and difficulty sleeping) when distinguishing GAD from NAD youth. When distinguishing GAD from SAD/SP youth, no physiological symptoms possessed high diagnostic efficiency. This finding may have resulted because children with anxiety disorders, in general, experience physiological symptoms, suggesting that physiological symptoms may not allow diagnosticians to distinguish between anxiety disorders. According to child report, no cut score on physiological symptoms favorably distinguished GAD youth and no child-reported physiological symptoms possessed high diagnostic efficiency. These findings contrast to Tracey and colleagues[18] who found that parent-reported irritability and youth-reported restlessness/being keyed up were predictive of GAD, whereas muscle tension was infrequently endorsed. Tracey and colleagues[18] compared 31 GAD youth to 13 youth with other anxiety disorders and 18 NAD youth. SAD and SP were infrequent diagnoses among the other anxiety comparison group which may explain the discrepant findings.

Many have noted the high comorbidity across the anxiety disorders[10–13] and it has been suggested that GAD, SAD, and SP share an underlying anxiety construct.[1,14] The present findings suggest GAD can be distinguished from SAD and SP. Comparisons of GAD and SAD/SP youth present the most conservative test of diagnostic utility, thus the cut score of three worry areas support a stringent manner by which to identify GAD youth.

The present study provides support for a preferred sequence for inquiring about GAD symptoms.[20] Interviewers may start by asking about the presence/absence of symptoms with the highest predictive value, followed by those symptoms with average prediction, and then symptoms with low predictive value. For parents, this would mean focusing on health of the child, health of significant others, and world affairs, while for children, focusing on school worry.

To meet DSM-IV criteria for GAD in youth it is necessary to experience excessive and uncontrollable worry across an unspecified number of areas for 6 months or longer and to experience one physiological symptom.[15] The lack of specificity regarding worry areas is problematic, and a better understanding of the number of worry areas most associated with a GAD diagnosis as well as the most diagnostically efficient worries is important. For example, a youth reporting school worry may qualify for GAD even though it is only one area because school worry is diagnostically efficient and covers much of the child’s life. However, if a child reports worry about world affairs alone, further inquiry may be warranted.

Revisions proposed for GAD by the DSM-V Work Groups[31] include requiring (1) excessive anxiety and worry in two or more domains for three months or more and (2) associated symptoms of restlessness/feeling keyed up/on edge, and/or muscle tension. The present data indicate, for children, more strict guidelines for GAD regarding the number of domains of worry (i.e., worry areas). Additionally, the proposed physiological symptom requirements for DSM-V are rather specific. Our results suggest physiological symptoms are rather non-specific for youth GAD. No specific physiological symptoms possessed sufficiently high diagnostic efficiency for discriminating GAD from other anxiety disorders, though physiological symptoms were commonly endorsed. Many anxious youth experience physiological symptoms (e.g., stomachache when separating from a caregiver in SAD). The data suggest four or more physiological symptoms (in contrast to one) optimally differentiate youth with GAD from youth with other anxiety disorders. Also, it may be that the physiological symptoms are nonspecific and suggest only the presence of any anxiety disorder.

Consistent with the literature, parent and child reports were discrepant.[32,33] Few children met diagnostic criteria solely based on their own report (though 44% met criteria for GAD by both parent and child report), children endorsed the presence of fewer worries and physiological symptoms than parents, and children’s self-report were less predictive than parent reports. This highlights the importance of obtaining multiple informant reports. The discrepant findings across informants are consistent with previous findings for SP[29] and GAD physiological symptoms[34] and may be due to child underreporting.[35] Comer and Kendall[35] demonstrated that parent–child reporting discrepancies for socially undesirable symptoms often occur due to the child not endorsing parent-reported symptoms, highlighting the need to obtain information from both parent and child when considering childhood anxiety diagnoses, particularly in the absence of a diagnostic gold standard. Parent report may be particularly important when diagnosing GAD in youth aged 7–13, given that GAD in younger children is frequently characterized by reassurance seeking behavior, verbalization of worries, and outward physiological symptoms (e.g., irritability). If the present results are replicated, it may suggest diagnosticians and clinicians place more weight on parent report of GAD symptoms in young children (though this may not be the case for adolescent reports).

The present study is not without limitations. First, the utility of symptoms reported on the ADIS-C/P were examined to diagnoses also obtained from the ADIS-C/P. Future studies would benefit from including an independent diagnostic instrument. Second, it is possible, though unlikely, that diagnosticians more readily diagnosed GAD in youth reporting more distressing symptoms (e.g., frequent difficulty sleeping) compared with youth endorsing lower levels of these symptoms. This possibility would benefit from further consideration. Finally, it should be noted that the anxiety-disordered youth in the present study were treatment-seeking; thus these findings may have limited generalizability to other populations.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute of Mental Health; Contract grant numbers: MH59087; MH80788, MH083333.

Footnotes

The authors disclose the following financial relationships within the past 3 years.

References

- 1.Bell-Dolan D, Brazeal TJ. Separation anxiety disorder, overanxious disorder, and school refusal. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am America. 1993;2:563–80. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowen RC, Offord DR, Boyle MH. The prevalence of overanxious disorder and separation anxiety disorder: Results from the Ontario Child Health Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:753–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199009000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costello EJ, Stouthamer-Loeber M, DeRosier M. Continuity and change in psychopathology from childhood to adolescence. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the society for research in child and adolescent psychopathology; Santa Fe, NM. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Last CG, Strauss CC, Francis G. Comorbidity among childhood anxiety disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175:726–30. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverman WK, Nelles WB. The anxiety disorders interview schedule for children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:772–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albano AM, Hack S. Children and adolescents. In: Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Mennin DS, editors. Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice. New York, NY: Guilford; 2004. pp. 383–408. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cantwell DP, Baker L. Stability and natural history of DSM-III childhood diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;29:691–700. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198909000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Last CG, Hersen M, Kazdin AE, et al. Comparison of DSM-III separation anxiety and overanxious disorders: Demographic characteristics and patterns of comorbidity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;26:527–31. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198707000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Last CG, Perrin S, Hersen M, Kazdin AE. DSM-III-R anxiety disorders in children: Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:1070–6. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beidel DC, Turner SM, Morris TL. Physiological, cognitive, and behavioral aspects of social anxiety. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:643–50. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Frequency and comorbidity of social phobia and social fears in adolescents. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37:831–43. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verduin T, Kendall PC. Differential occurrence of comorbidity within childhood anxiety disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32:290–5. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wittchen H-U, Stein MB, Kessler RC. Social fears and social phobia in a community sample of adolescents and young adults: Prevalence, risk factors, and co-morbidity. Psychol Med. 1999;29:309–23. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pine DS, Grun J. Anxiety disorders. In: Walsh TB, editor. Child psychopharmacology: Review of psychiatry series. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 1998. pp. 115–148. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, D.C: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendall P, Warman M. Anxiety disorders in youth: Diagnostic consistency across DSM-III-R and DSM-IV. J Anxiety Disord. 1996;10:452–63. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Comer J, Kendall PC, Franklin M, et al. Obsessing/worrying about the overlap between obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in youth. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:663–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tracey SA, Chorpita BF, Douban J, Barlow DH. Empirical evaluation of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder criteria in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Psychol. 1997;26:404–14. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2604_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pina AA, Silverman WK, Alfano CA, Saavadra LM. Diagnostic efficiency of symptoms in the diagnosis of DSM-IV: Generalized anxiety disorder in youth. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2002;43:959–67. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverman WK, Ollendick TH. Evidence-based assessment of anxiety and its disorders in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34:380–411. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silverman WK, Albano AM. Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Boulder, CO: Graywind Publications Incorporated; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pina AA. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:937–44. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, et al. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31(335):342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapee R, Barrett P, Dadds M, Evans L. Reliability of the DSM-III-R childhood anxiety disorders using structured interview: Interrater and parent-child agreement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:984–92. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthey S, Petrovski P. The Children’s Depression Inventory: Error in cutoff scores for screening purposes. Psychol Assess. 2002;14:146–9. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zweig MH, Campbell G. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) plots: A fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine. Clin Chem. 1993;39:561–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frick P, Lahey B, Applegate B, et al. DSM-IV field trials for the disruptive behavior disorders: Symptom utility estimates. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:529–39. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199405000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puliafico AC, Comer JS, Kendall PC. Social phobia in youth: The diagnostic utility of feared social situations. Psychol Assess. 2007;19:152–8. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lonigan CJ, Anthony JL, Shannon MP. Diagnostic efficacy of posttraumatic symptoms in children exposed to disaster. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998;27:255–67. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2703_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Psychiatric Association. [Accessed 2010 February 10.];Proposed draft revisions to DSM disorders and criteria. 2010 http://www.dsm5.org/Pages/Default.aspx.

- 32.Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlates for situational specificity. Psychol Bull. 1987;101:213–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grills AE, Ollendick TH. Multiple informant agreement and the anxiety disorders interview schedule for parents and children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:30–40. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kendall P, Pimentel S. On the physiological symptom constellation in youth with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:211–21. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Comer JS, Kendall PC. A symptom-level examination of parent-child agreement in the diagnosis of anxious youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:878–86. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000125092.35109.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]