Abstract

Context

Atypical apocrine adenosis is a rare breast lesion in which the cellular population demonstrates cytologic alterations that may be confused with malignancy. The clinical significance and management of atypical apocrine adenosis are unclear because of the lack of long-term follow-up studies.

Objective

To determine the breast cancer risk in a retrospective series of patients with atypical apocrine adenosis diagnosed in otherwise benign, breast excisional biopsies.

Design

We identified 37 atypical apocrine adenosis cases in the Mayo Benign Breast Disease Cohort (9340 women) between 1967 and 1991 with a blinded pathology rereview. Breast cancer diagnoses subsequent to initial atypical apocrine adenosis biopsy were identified (average follow-up, 14 years).

Results

The mean age at diagnosis of atypical apocrine adenosis in the group was 59 years. Breast carcinoma subsequently developed in 3 women (8%) with atypical apocrine adenosis, diagnosed after follow-up intervals of 4, 12, and 18 years. The tumor from 1 of the 3 cases (33%) was ductal carcinoma in situ, contralateral to the original biopsy, and the other 2 cases (66%) were invasive carcinoma. Ages at the time of diagnosis of atypical apocrine adenosis were 55, 47, and 63 years for those that developed in situ or invasive carcinoma.

Conclusions

(1) Atypical apocrine adenosis was a rare lesion during the accrual era of our cohort (<1% of cases); (2) women found to have atypical apocrine adenosis were, on average, older than were other patients with benign breast disease, however, there does not seem to be an association with age and risk for developing carcinoma in patients diagnosed with atypical apocrine adenosis, as previously suggested; and (3) atypical apocrine adenosis does not appear to be an aggressive lesion and should not be regarded as a direct histologic precursor to breast carcinoma.

The presence of benign breast disease (BBD) is widely accepted as a risk factor for subsequent development of breast cancer. A wide range of microscopic lesions may occur in biopsies from women with BBD; these have differing correlations with subsequent breast cancer risk, depending on the amount and type of epithelial hyperplasia. For purposes of risk stratification, these microscopic findings are classified as nonproliferative, proliferative without atypia, or proliferative with atypia. Many specific proliferative or atypical lesions (eg, atypical ductal or lobular hyperplasia) have been shown to correlate increased risk relative to age-matched control populations. However, the pathologic spectrum of benign breast disease is protean and, therefore, many distinctive lesions are less well understood because of the rarity of the diagnosis and the lack of follow-up data.

An example of the complex histopathology of BBD is the spectrum of lesions with apocrine differentiation, ranging from the common finding of apocrine metaplasia in simple cysts to frankly invasive carcinoma with apocrine morphology.1,2 Within this spectrum, apocrine atypia is defined cytologically as a 3-fold nuclear enlargement with prominent pleomorphic nucleoli.3 It is well recognized that the cytologic alterations can be misdiagnosed as apocrine ductal carcinoma in situ (apocrine DCIS) if pathologists do not apply diagnostic criteria for atypical apocrine adenosis (AAA). Atypical apocrine lesions that have been described in the literature include AAA, atypical apocrine metaplasia, and atypical apocrine hyperplasia.3,4 These lesions are uncommon and, therefore, the literature includes only a few, small case series, all with limited follow-up. Hence, it is not known whether AAA conveys significantly increased risk for subsequent breast cancer.

The objective of this study was to determine the breast cancer risk in a retrospective series of patients diagnosed with atypical apocrine adenosis in otherwise benign breast excisional biopsies. Specifically, we sought to answer the question whether atypical apocrine adenosis should be considered a marker of increased risk and/or direct precursor lesion to subsequent breast carcinoma based on long-term clinical follow-up.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The derivation, pathologic analysis, and characteristics of our study population have been reported previously.5 Briefly, the Mayo Benign Breast Disease Cohort (Rochester, Minnesota) included all women 18 to 85 years of age who had undergone surgical excision or excisional biopsy of a benign breast lesion during the 25-year period between 1967 and 1991. The study cohort included 9340 women, after exclusion of those women with a diagnosis of invasive or in situ breast cancer before, or within, 6 months following the benign biopsy, mastectomy, or breast reduction at or before biopsy, refusal to consent use of their medical records for research, or unavailable biopsy specimens for review. Breast cancer diagnoses subsequent to the initial benign biopsy were identified through questionnaires and multiple queries of computerized records. The average follow-up of patients in the overall cohort was 14 years.

We searched our cohort database to identify all recorded cases of AAA. Histologic rereview of original slides was performed for confirmation of diagnosis. Our database was also searched for the presence of subsequent breast cancer in each patient with confirmed AAA, which was further characterized by the interval following biopsy and laterality (with respect to benign biopsy). Finally, all other histologic findings in the original biopsy were reviewed and compared.

RESULTS

Figures 1 through 3 illustrate the pathology of AAA. The lesions were highly cellular and typically tumefactive, rather than focal, forming confluent masses of 3 to 6 mm (as measured on the slides). Sclerosing adenosis and calcification accompanied nearly every case. Cytologic atypia was patchy and focal, creating a heterogeneous mixture of enlarged and normal nuclei. Mitoses and individual cell necrosis were absent, as were distended acinar structures. Four cases had concurrent atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), and one had atypical lobular hyperplasia. Other findings at biopsy are detailed with comparison to those cases that later developed in situ or invasive carcinoma and the rest of the AAA cases in the Table.

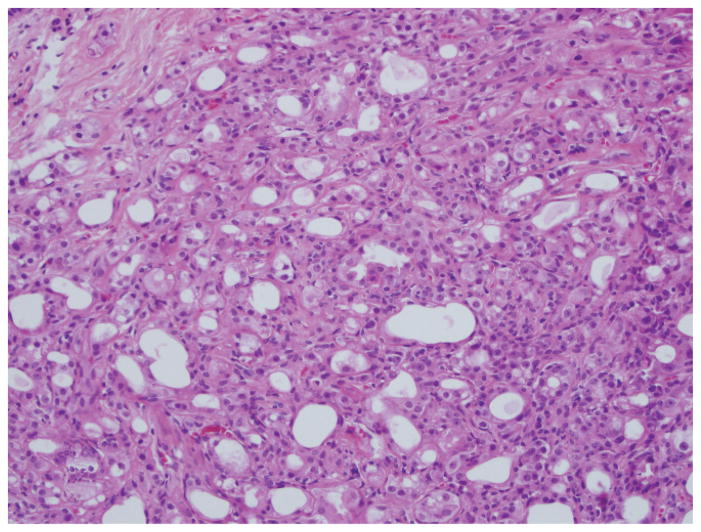

Figure 1.

Atypical apocrine adenosis demonstrating a highly cellular and tumefactive growth pattern, forming a confluent cellular mass (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×200).

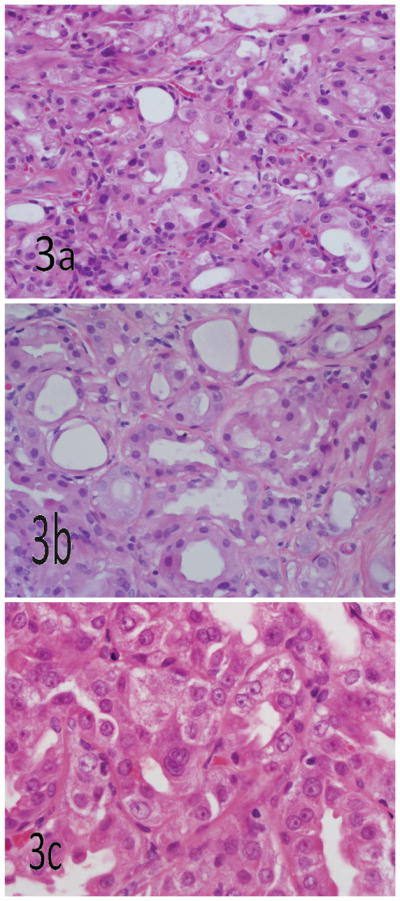

Figure 3.

Cytologic atypia is patchy and focal in atypical apocrine adenosis, creating a heterogeneous mixture of enlarged and normal nuclei. Mitoses, significant nuclear membrane irregularities, and individual cell necrosis are absent in atypical apocrine adenosis (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnifications ×400 [a and b] and ×600 [c]).

Table 1.

Table Comparison of Clinical Data and Additional Histologic Findings at the Time of Benign Biopsy in Patients With Atypical Apocrine Adenosis, With and Without Later Breast Cancer

| Subsequent Cancer Status | Cases, No. | Age at Biopsy, y | Follow-up, y | Mild DH | MDH | FDH | ADH | ALH | Calcs | SA | FA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No cancer | 34 | 59.7 | 14 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 27 | 32 | 3 |

| Cancer | 3 | 55.0 | 11.3a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

Abbreviations: ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia; ALH, atypical lobular hyperplasia; Calcs, calcifications; DH, ductal hyperplasia; FA, fibroadenoma; FDH, florid ductal hyperplasia; MDH, moderate ductal hyperplasia; SA, sclerosing adenosis.

Mean follow-up to diagnosis of carcinoma.

Of the 9340 women included in the cohort, 37 cases (0.4% of total) of AAA were identified. The mean age at diagnosis of AAA for all patients in the group was 59.3 years versus 51.4 years for the cohort overall. Three women (8%) with AAA subsequently developed in situ or invasive breast carcinoma versus 7.8% for the cohort overall. The ages at the time of diagnosis of AAA for those who developed in situ or invasive carcinoma were 55, 47, and 63 years, with follow-up intervals of 4, 12, and 18 years, respectively, to the diagnosis of carcinoma.

Two of the 3 women (66%) developed invasive carcinoma ipsilateral to the original biopsy of AAA after 4 and 18 years of follow-up. The single case of contralateral DCIS was diagnosed after a 12-year interval in the contralateral breast. The patient who developed ipsilateral invasive ductal carcinoma after only 4 years of follow-up also had ADH and calcifications in addition to the AAA in the original biopsy. The third cancer case was an ipsilateral invasive mammary carcinoma with mixed ductal and lobular features, 18 years after the original biopsy. After excluding the single case with ADH in addition to AAA in the original excisional biopsy, 5.4% of women (2 of 37) subsequently developed in situ or invasive carcinoma. There was no AAA in the background breast parenchyma of the subsequent cancers, and there was no evidence of apocrine differentiation of the tumors.

COMMENT

The results of our study confirm that AAA is a rare lesion, at least before the era of needle core biopsy from which our BBD cohort was derived, because it represented less than 0.4% of all benign breast diagnoses. To put that in perspective, ADH and atypical lobular hyperplasia (combined) were seen in biopsies from approximately 10 times as many of the cohort subjects.5 Although we have no direct evidence that AAA is associated with highly suspicious abnormalities on imaging, we suspect from anecdotal observation that AAA has become more commonly encountered in recent years, because of increased use of needle core biopsy techniques. Hence, pathologists may increasingly encounter AAA in clinical material. The low prevalence of AAA in our cohort limits interpretation of the outcome data and risk of subsequent carcinoma. Despite a limited number of patients, however, our study has the advantage of lengthy follow-up. Our study showed the rate of breast cancer diagnosis in follow-up of AAA cases (8.1%) was not appreciably different from that of the cohort overall (7.8%). Given that 1 of the 3 patients with AAA who later developed carcinoma also had ADH in the original biopsy, the rate of breast cancer may be slightly less when identified as an independent finding. Further, the interval to cancer diagnosis (mean, 11.3 years) does not imply that the patients had unstable precursor lesions. Based on these findings, we would conclude that there is no current evidence to consider AAA as a high-risk or precursor lesion, which is how ADH and atypical lobular hyperplasia should be considered.

There are only 2 published studies in the literature that have reported outcome following the diagnosis of AAA in a benign biopsy, neither of which is derived from a patient cohort. Seidman et al6 reviewed 37 cases of AAA with a mean follow-up of 8.7 years. They reported that 4 women subsequently developed invasive ductal carcinoma, of which, 3 were ipsilateral and 1 was contralateral. This study also reported an increased relative risk in women older than 60 years, compared with those diagnosed at a younger age. Carter and Rosen7 reviewed 51 cases of atypical apocrine metaplasia in sclerosing lesions and reported that none of the 47 women with intact breasts (4 women had misdiagnosis and subsequent mastectomy) developed breast carcinoma within the average follow-up period of 35 months (12–76 months). They also reported the average age at diagnosis in their study was 58 years and recommended that continued clinical observation is advisable as long-term clinical implications are yet to be determined. They made no suggestion regarding the type of observation and acknowledged that the roughly 3-year average follow-up was a limiting factor in drawing any definitive conclusions about the risk for developing carcinoma. Similar to our study, these studies also identified an association of older age with AAA, suggesting that development of AAA may be age-related.

The uncommon nature of AAA introduces the possibility of misdiagnosis, particularly because the diagnostic criteria to distinguish AAA from apocrine DCIS are subtle and not clinically validated. This problem is compounded by apocrine atypia not being a single entity but rather a part of a wide spectrum of breast lesions with apocrine features, ranging from common, benign, proliferative changes to in situ to invasive carcinomas with apocrine differentiation. Although nuclear enlargement and hyper-chromasia are accepted findings in apocrine atypia, the presence of nuclear membrane irregularity, appreciable mitotic activity, or individual cell necrosis are worrisome findings that suggest the possibility of apocrine DCIS.8 Atypical apocrine adenosis may involve sclerosing lesions, but by definition, it lacks distended epithelium-lined spaces or complex architectural features of DCIS. None of our cases demonstrated large duct involvement (ie, by apocrine atypia). Finally, in addition to the sometimes subtle microscopic features that distinguish apocrine atypia from low-grade apocrine DCIS, pathologists should bear in mind that apocrine atypia may be observed in the background of patients with apocrine DCIS.9

The effect of changes in breast cancer screening protocols, including mammographic techniques as well as the criteria for sending women for biopsies based on the mammographic findings, have evolved significantly during the past 20 years. It is still unclear whether AAA lesions associated with calcifications are more worrisome on mammography than usual “benign calcifications” because we do not have detailed imaging data for these patients. Furthermore, all of the specimens we studied were surgical excisional biopsies rather than core needle samples. Hence, the need for surgical excision of AAA identified at core biopsy in today’s clinical practice is unknown. When AAA is encountered in a core biopsy, we would recommend consideration of surgical excision, mostly because of the difficulty of categorically excluding DCIS in the setting of limited material, as suggested by other authors.2 Despite these limitations, based on the extended follow-up data available, our findings suggest that AAA is not an aggressive lesion or an unstable, direct, histologic precursor to breast carcinoma. Patients with AAA do not appear to have an increased risk of breast cancer compared with women with other BBDs.

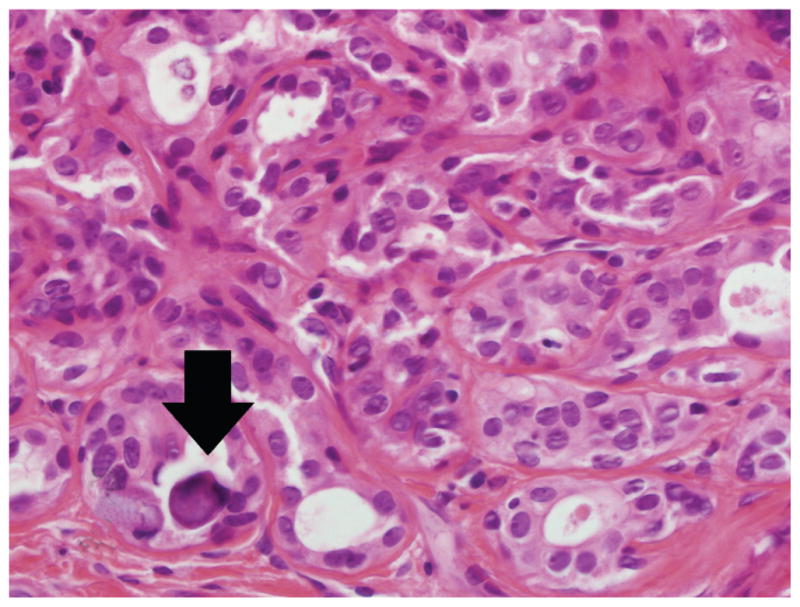

Figure 2.

Calcification (arrow) accompanies nearly every lesion of atypical apocrine adenosis (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×600).

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

Presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology; February 28, 2011; San Antonio, Texas.

References

- 1.Durham JR, Fechner RE. The histologic spectrum of apocrine lesions of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113(5):S3–S18. doi: 10.1309/7A2P-YMWJ-B1PD-UDN9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells CA, El-Ayat GA. Non-operative breast pathology: apocrine lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(12):1313–1320. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.040626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Malley FP, Bane AL. The spectrum of apocrine lesions of the breast. Adv Anat Pathol. 2004;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purcell CA, Norris HJ. Intraductal proliferations of the breast: a review of histologic criteria for atypical intraductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ, including apocrine and papillary lesions. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1998;2(2):135–145. doi: 10.1016/s1092-9134(98)80051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(3):229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seidman JD, Ashton M, Lefkowitz M. Atypical apocrine adenosis of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 37 patients with 8.7-year follow-up. Cancer. 1996;77(12):2529–2537. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960615)77:12<2529::AID-CNCR16>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter DJ, Rosen PP. Atypical apocrine metaplasia in sclerosing lesions of the breast: a study of 51 patients. Mod Pathol. 1991;4(1):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leal C, Henrique R, Monteiro P, et al. Apocrine ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: histologic classification and expression of biologic markers. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:487–493. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.24327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visscher DW. Apocrine ductal carcinoma in situ involving a sclerosing lesion with adenosis: report of a case. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(11):1817–1821. doi: 10.5858/133.11.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]