Abstract

AIM

This study investigated how parents living with HIV communicated about HIV prevention with their 10–18 year old children.

METHODS

Interviews with 76 mothers and fathers were analyzed for (1) their experiences discussing HIV prevention with adolescents, and (2) advice on how to best broach HIV-related topics.

RESULTS

Interactive conversations, where both parents and adolescents participated, were regarded as effective. Parents emphasized that adolescents should have a “voice” (be able to voice their concerns) and a “choice” (have a variety of effective prevention strategies to choose from) during HIV-related talks.

DISCUSSION

A five step process for interactive communication emerged as a result of these discussions.

IMPLICATIONS

Health care professionals can facilitate adolescent sexual health by encouraging parents to actively involve their children in discussions about HIV prevention.

CONCLUSION

Future HIV prevention programs could benefit by providing parents with appropriate tools to foster interactive discussions about sexual health with adolescents.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS prevention education, qualitative research, HIV/AIDS knowledge, sexual risk-taking, parent-adolescent communication

Introduction

Almost 40% of new HIV infections in the United States occur in adolescents and young adults, with the large majority a result of sexual transmission (Prejean et al., 2011; CDC, 2012). Misconceptions about how to effectively prevent sexually transmitted infections are widespread, whereas consistent condom use and concern about contracting HIV is low (CDC, 2008; DiClemente, Crosby, & Wingood, 2002; KFF, 2009; Manlove, Ikramullah, & Terry-Humen, 2008). This combination of characteristics (e.g., inconsistent condom use, lack of effective prevention knowledge, and low perceived risk, among other factors) can greatly exacerbate the risk of adolescent HIV infection.

Youth who already have a parent living with HIV/AIDS are no exception to behavioral HIV risk. Chabon, Futterman, & Hoffman (2001) found that adolescents who had a mother living with HIV were more likely to have sex at younger age, report risky sexual behavior (including exchanging sex for money, drugs, or living accommodations), have multiple (10 or more) sex partners, and report a history of sexual abuse. Subsequent reports have yielded mixed results on what effect (if any) parental HIV status has on youth risk behavior, with some reporting lower rates of sexual intercourse among these youth (Murphy, Herbeck, Marelich, & Schuster, 2010) and others reporting higher rates, riskier sexual behavior, and an earlier sexual debut (Cederbaum, 2009; Lee, Lester, & Rotheram-Borus, 2002; May, Lester, IIardi, & Rotheram-Borus, 2006). These differences could reflect a variety of factors, including variations in parental health, substance abuse, and/or the degree to which parents and youth were receiving supportive psychosocial services (Leonard, Gwadz, Cleland, Vekaria, & Ferns, 2008; Mellins et al., 2007). Regardless, many adolescents in families affected by HIV are impacted by psychosocial, environmental, and behavioral factors that could increase their chances of acquiring HIV infection (Murphy, 2008; Lichtenstein, Sturdevant, & Mujumdar, 2010). Thus, there is an imminent need for programs that educate parents and youth about HIV and equip them with effective strategies to prevent further transmission of HIV (Mellins et al., 2007).

One promising psychosocial HIV prevention approach has been to increase parent-child discussions about sexual health and safety (CDC, 2008; Miller et al., 2011). Research demonstrates that youth rely heavily upon their parents’ influences when making sexual decisions, and that the majority wish they could have open discussions with their parents about sexual topics (Albert, 2004). Frequent parent-adolescent conversations about sexual topics have been linked to a variety of protective behaviors among youth, including safer sexual practices and a decreased risk of HIV transmission (Lehr, DiIorio, Dudly, & Lipana, 2000; Leland & Barth; 1993; Pick & Palos, 1995; Sneed, 2008). Studies from the larger parent-adolescent communication (on families where a parent is not known to have HIV) document that effective conversations about sexual health (a) occur early in adolescence (before the onset of sexual activity) (Dittus, Miller, Kotchick, & Forehand, 2004), (b) take place frequently (Dittus, Jaccard, & Gordon, 1999), (c) are comprehensive (employing a variety of topics) (Dutra, Miller, & Forehand, 1999), (d) have good quality (conversations are informative and relatively comfortable) (Dittus et al., 2004), and (e) occur within supportive parent-child relationships (adolescents are generally satisfied with the maternal-child relationship) (Dittus & Jaccard, 2000). In addition, conversations are more likely to be effective if they are interactive as opposed to dominated by the parent (DiIorio, McCarty, & Pluhar, 2008), and if the parent is open, competent, and comfortable during sexual communication discussions (Whitaker, Miller, May, & Levin, 1999). Finally, cultural differences exist in family communication about HIV prevention, with some reports suggesting that African Americans and/or Latino families talk less frequently and report lower levels of knowledge than Caucasian families; similarly families of lower socioeconomic status have been found to talk less frequently and report lower levels of knowledge than families of higher socioeconomic status (Tinsley, Lees, & Sumartojo, 2004).

Given that communication behaviors are generally regarded as modifiable, studies that describe and identify effective communication practices are needed to design parent-adolescent communication interventions (Riesch, Anderson, & Kreuger, 2006). Indeed, Lefkowitz, Sigman, and Au (2000) found that mothers who underwent a communication skills training program were able to conduct more interactive conversations about sexuality and AIDS with their adolescents, compared to mothers who did not participate in the experimental training program. The mothers in the experimental group had a greater level of AIDS knowledge, asked an increased number of open-ended questions during conversation, and decreased the amount of time they spoke (to allow the adolescent greater participation in the conversation).

Unfortunately, there is little practical guidance available in the academic literature for parents living with HIV on how to initiate interactive discussions about sexual health with adolescents, either from experts or from parents themselves. Parents may benefit from advice on how to involve adolescents in conversations about sexual health and safety, including the timing, strategies used, content, and conversational style for such discussions (DiIorio et al., 2008; DiIorio, Pluhar, & Belcher, 2003). Families affected by HIV face additional considerations and challenges when broaching preventive discussions, including issues of stigma, household safety, and how to discuss prevention in families where children are both HIV+ and HIV− (Bogart et al., 2008; Authors, 2012; Corona et al., 2009). The purpose of this article is to inform both parents with HIV and the health care professionals who support them of the strategies other parents have found to be effective in their communicative interactions with adolescents.

Method

Sample

Participants consisted of 76 parents or guardians living with HIV or AIDS in Illinois and Indiana, who were interviewed as part of a larger study on communication about HIV and HIV prevention (see Authors, 2012 for detailed study methodology). Participants were included in the study if they met the following criteria (assessed by self-report): (a) a diagnosis of HIV or AIDS, (b) the parent or guardian of at least one child ages 10–18 who is not infected with HIV, and (c) living with or having frequent (at least monthly) contact with their adolescent for the past year. One parent per family was interviewed and received $30 for their participation in the study. All necessary institutional review board (IRB) approvals were obtained prior to recruitment. Parents were recruited for the study via fliers place in HIV/AIDS service organizations (e.g., public health departments, university hospitals, and non-profit organizations) in 2009–2010. Fliers listed a toll-free number where parents could call in and arrange a time to be interviewed.

Procedures

During the interview session, each parent filled out a family tree (15 minutes), underwent an in-depth interview about their experiences discussing HIV and HIV prevention with adolescents (1 hour), and completed a questionnaire with demographic and health-related information (15 minutes). The interview script was constructed after a thorough review of the relevant psychological, medical, health behavior, health communication, and family studies literature. Questions were worded (where relevant) to be consistent with previous qualitative measures of parent-adolescent HIV risk communication (DiIorio et al., 2003) and with previous scholarship assessing the subjective effectiveness of particular communication strategies (Goldsmith, Bute, Lindholm, 2011; Kosenko, 2010). For example, parents were asked if they thought some ways of talking about HIV prevention worked “better” than others, to provide examples of ways that had worked well and not as well within their family, and to provide other parents with advice on how to broach HIV-related topics. The interview script was reviewed by both HIV content experts and experts in instrument development and pilot tested by a group of parents with HIV. Interviews were constructed to last approximately one hour to allow for sufficient depth of participant responses. Participants had the choice of being interviewed in their homes, at their local HIV/AIDS service organization, or in a private room in a public meeting location of their choice (e.g., a private room in a public library); the majority chose to be interviewed in their homes. All interviews were conducted by the first author, a graduate student with previous qualitative research and in-depth interview experience.

Data Analysis

Participant interviews were recorded (voice only), transcribed, cleaned to remove identifying information, and loaded into a software system for organizing qualitative data (Nvivo version 8.0, QSR International, Cambridge, MA). Each participant was assigned a pseudonym to protect confidentiality. Interviews lasted an average of 54 minutes (range 20–140 minutes), for a total of 69 hours of voice recordings and 1,497 pages of single-spaced text.

Interview data were coded over a period of several months, using a grounded theory approach to systematically analyze recurring themes (Charmaz, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Four coders met and coded approximately 30% of the transcripts, looking specifically for themes related to effective and interactive parent-child communication, as well as advice parents had on how to converse effectively with adolescents. All coders were either graduate students with previous grounded theory coding experience or faculty members with a wide range of experiences coding qualitative interviews. A codebook (based on MacQueen, McLellan, Kay, & Milstein, 1998) was created for each theme. Once final codes had been agreed upon, the first author analyzed the remainder of the transcripts and the second author provided inter-rater reliability checks on a random 10% of the example quotes in each code. The coders initially agreed upon 95% of examples in each code, and discussed any remaining discrepancies until 100% agreement was reached.

Theoretical memos were kept throughout the entire interview and data analysis process, in order to systematically reflect on the strategies parents deemed effective and how they compared to one another (Charmaz, 2006). Examples from participant transcripts were compared both within and across interviews. Discussions between coders and other “peer debriefing sessions” were employed as methods to enhance the credibility of study findings (Thomas & Magilvy, 2011).

Sample Demographics

Parents

The majority participants (92%) were biological parents, whereas the remaining 8% were primary caregivers and/or legal guardians, including five grandparents and one aunt. Approximately 63% were mothers; 37% were fathers. The average age of participants was 47 years. Two-thirds of parents had disclosed their HIV status to their children; 8% also had a child who was HIV+.

Children

Collectively, the parents in this sample cared for 286 children with an average of four children per family. The smallest family had one child and the largest had nine children. Parents reported a total of 136 adolescents between the ages of 10 and 18. The average age of adolescents was 15 years. The majority of parents (76%) reported daily contact with at least one adolescent in the age range of the study. Other parents reported average contact ranging from multiple times per week to multiple times per month, representing a range of complex family structures and living situations. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of parents and their children.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of parents and adolescents.

| Characteristic | No. of Participants | % of N |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Parent Gender | ||

| Female | 48 | 63.2 |

| Male | 28 | 36.8 |

| Parent Age (years) | ||

| 27–39 | 14 | 18.7 |

| 40–49 | 32 | 42.7 |

| 50–65 | 29 | 38.7 |

| Parent Race/Ethnicity | ||

| African American or Black | 55 | 72.4 |

| Caucasian or White | 9 | 11.8 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 | 11.8 |

| Asian | 1 | 1.3 |

| Other | 2 | 2.6 |

| Parent Education Level | ||

| Less than high school | 22 | 28.9 |

| High school or GED | 46 | 60.5 |

| 4 year college degree | 7 | 9.2 |

| Advanced degree | 1 | 1.3 |

| Parent Relationship Status | ||

| Single | 31 | 40.8 |

| Dating | 9 | 11.8 |

| Long-term relationship | 18 | 23.7 |

| Married | 16 | 21.1 |

| Other | 2 | 2.6 |

| Adolescent gender | ||

| Female | 76 | 55.9 |

| Male | 60 | 44.1 |

| Adolescent age (years) | ||

| 10–12 | 33 | 24.3 |

| 13–15 | 41 | 30.1 |

| 16–18 | 62 | 45.6 |

Results

Parents in our sample reported talking about a variety of topics with adolescents during HIV prevention talks, including the various ways HIV was transmitted, how to stay safe from HIV infection at home, methods of birth control and how to use them, and family values surrounding sexual activity and drug and alcohol use. Some parents also advised that it was helpful to begin such conversations when they were in good health, when they and their children were on relatively “normal” terms (as opposed to times of high family stress and/or strained parent-child relationships), and when they knew they had the resources and support necessary to engage in such conversations (e.g., friends, family members, or health care providers who were willing to encourage and/or support them).

Approximately half of the parents we spoke with emphasized the effectiveness of having interactive conversations with adolescents about HIV prevention, or gave examples of “ways that worked well” that happened to include both the parent and child conversing (without necessarily verbalizing that these conversations were interactive). For purposes of this manuscript, interactive conversations were defined as conversations where, at a minimum, the parent and child took turns speaking during the conversation (Lefkowitz, Sigman, & Au, 2000), and/or instances where parents and children discussed HIV prevention while engaged in an activity together. Parents who were not coded as using interactive strategies, in contrast, were those who mentioned parent-directed conversations or no conversation at all (e.g., telling adolescents how HIV was transmitted without involving them in the conversation, informing youth of what sexual behavior was “acceptable” without eliciting a response, or handing a book or pamphlet to their adolescent for them to read on their own).1

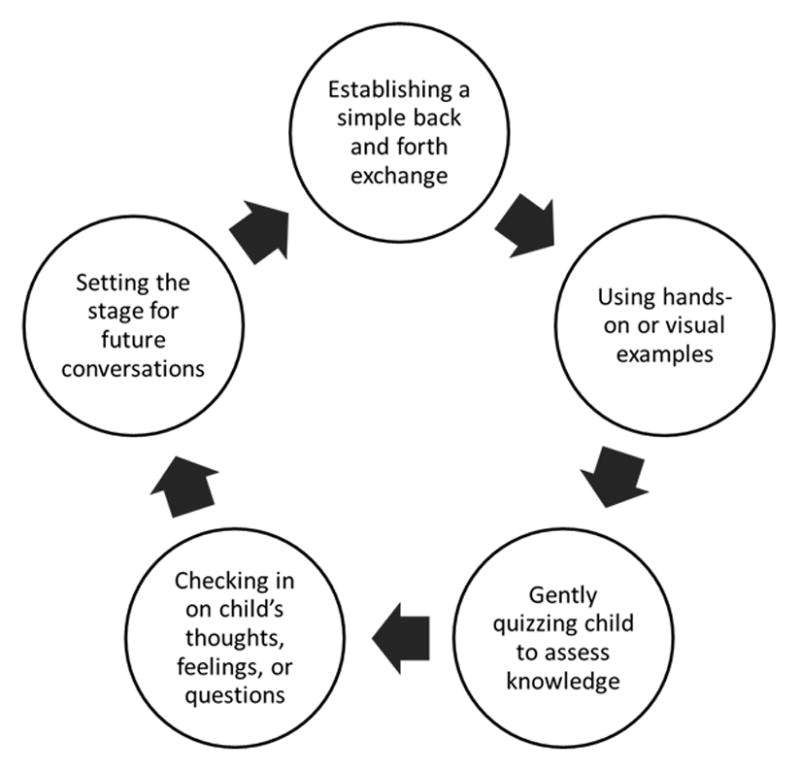

Overall, parents who used interactive strategies explained that it was important for adolescents to have a “voice” (e.g., be able to voice their concerns) and a “choice” (e.g., have a variety of effective prevention strategies to choose from) when it came to matters of sexual health and safety. Rather than have a one-time, parent-directed talk about puberty, sex, and contraception, parents sought to have interactive conversations over time, allowing adolescents a range of opportunities to learn about HIV-related topics. Parents who spoke of actively involving adolescents in prevention dialogues did so in a variety of ways. Although they emphasized the importance of “knowing one’s child” and “doing what works best for your family,” most parents went through similar steps to include their adolescent(s) in preventive talks. A five step process emerged after analyzing parents’ conversations on these topics (see Figure 1). Each of these components is described in greater detail in the following section, with exemplar quotes from parents. A summary of practical guidance for parents stemming from these findings is presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

A five step process for interactive parent-adolescent communication about HIV prevention.

Table 2.

Summary of study findings reported in a practical format for parents.

| Topic | Practical guidance for parents |

|---|---|

|

| |

| General information |

|

| What you and your child might talk about |

|

| When to talk |

|

Ways to include children in talks

|

|

Note. A link to a complete brochure with practical guidance for parents is available at: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/46417.

Step #1: Establishing a simple back-and-forth exchange

Sometimes involving adolescents in dialogue was as simple as taking turns speaking during conversations. For example, when asked what conversations about HIV prevention she thought had “gone well” with her 16 year old granddaughter, Debbie responded with the following anecdote:

She used to say, “I go with him” [as in going out or dating]. [I was like] “Go with him where?” I’ll be messing with her. [Laughs] “Where you going with him? Where ya’ll going?” [She’d be like] “Grandma, you know! We go together,” I’d say, “Where you all go? Where ya’ll be going?” She say, “Grandma, you know!” I say, “No I don’t, where ya’ll going? Whatcha’ all be doing when you go?”

By gently making fun of and pretending not to understand her granddaughter’s terminology for dating, Debbie was able to engage her in the conversation and eventually move the dialogue to more direct talk about how to date safely. Not all examples of back and forth exchanges employed humor or joking, but all parents who used this technique noted that it allowed (and even encouraged) adolescents to participate in preventive conversations.

Another example of a mother referring to establishing a simple back-and-forth conversation included:

[A good way would be if] my daughter were to come to me and tell me, you know, “I’m thinking about having sex with so-and-so.” Alright, just sit down and talk about it. You know, “What steps are you willing to take to protect yourself? What steps is he willing to take to protect himself? Have you asked him about his sexual history? Is he active? Has he been tested for anything?”

This mother emphasized that, even relatively personal topics (if approached logically and with concern) provided relatively straightforward opportunities to discuss HIV prevention with adolescents.

Step #2: Using hands-on or visual examples

Another interactive strategy parents deemed effective (and relied heavily upon) was using hands-on or visual examples. This included situations where parents used pictures, pamphlets, presentations, field trips, games, or condom demonstrations to help explain preventive topics. As Robert, father of two sons ages 17 and 18, explained:

What I did was look on the internet [and said], “Oh look, herpes, okay, look, a picture!” and syphilis, gonorrhea. I told them, “Come here, you gotta see this!” I was actually sitting in the bedroom with the laptop [and said] “Come here, look! See what I’m gonna use at work.” They’re going, “Oh gross! What is that!?” I said, “That is herpes.”…They were going like, “Oh Dad that is so sick, what is that for, what’d you look that up for?” “I’m just showing you what it looks like,” I said, “So you’ll know.” I said “Put a hat [condom] on it, unless you want this. [Laughs] Look, you want to see the other one I got? Do you know how to prevent it? Put a hat on it.”

Similarly, Nancy had created games and flash cards to teach her 10 year old daughter about how HIV was transmitted:

I just use different techniques….Sometimes I use card games. Like, I might get flash cards and I like have her sit down at the table, and we have popcorn and I just go over, you know, I’ll put like “Dirty needles” [on one card], and on another card “STD”, and [then] “Prevention”. Like [different] questions. We talk about it -- I put prevention up and she says “What’s prevention?” I say, “To prevent things from happening, like a situation”, and she’ll say “Ok, I understand now” and then you get her more involved. She likes those games.

Kallyn, on the other hand, liked to follow up prevention conversations with field trips or activities where she could visually point out potential consequences of being involved with gangs, drugs, and sexual promiscuity. Based upon her experiences as mother of a 12 year old daughter and guardian of her 13 and 14 year old nephews and 18 year old niece, she advised:

Show them what can happen. Don’t just talk and talk and talk. Show them reality because that’s what they need to see. Find shelters where they can go and see kids their ages going through what they’re going through. Take them places like adoption agencies so that they see what that is like. Take them to DCFS to see it. Ask questions. Take them to the jails and stuff so they can see. You know, you can tell them all day long, but they have to see it too. They have to see it and experience it.

Kallyn had been able to use these various experiences as segues into HIV-related safety information. Other parents showed adolescents how to put condoms on and then had the adolescent demonstrate that he or she knew how to do so. Altogether, the parents who gave examples of using hands-or visual examples appeared to be highly knowledgeable, comfortable, and skilled in discussing HIV prevention. They were able to take the factual and/or experiential knowledge they wanted to teach and creatively engage adolescents in prevention-related material.

Step #3: Quizzing child to elicit prior knowledge or demonstrate mastery

Along the lines of playing games to teach HIV prevention, some parents commented on the usefulness of calmly quizzing adolescents to encourage interaction. Parents generally quizzed their children for three separate purposes: (1) to elicit an adolescent’s knowledge of HIV or related material prior to engaging in conversation, (2) to demonstrate mastery of a topic discussed previously, or (3) to practice different sexual or drug-related scenarios with the adolescent (e.g., condom negotiation skills, being assertive about finding out the sexual history of romantic partners).

When it came to eliciting prior knowledge from adolescents, parents would typically ask questions like “What have you heard about HIV or AIDS?,” or “Do you know anyone who is HIV positive?” For example, Eyana (mother of five, including a 6 year old son living with HIV) began discussing HIV and HIV prevention with her 17 year old daughter two years ago. As she relayed:

I was trying to basically give her a wakeup call. You know, “You’re out here sleeping around and doing stuff.” And I just went into the conversation asking her “Do you know what a person with HIV looks like?” [She said], “Yeah, they’re skinny and they’re sick and they look all crazy.” I said, “Well does your brother look like that?” [She said] “No.” I said, “Do I look like that?” She said, “No.” And I was like “Well, we are both HIV positive.”

As Eyana conveys, parents sometimes used their own HIV status to teach lessons about sexual health and safety (e.g., that you can’t tell a romantic partner has HIV just by looking at them). In other instances, parents would purposely withhold preventive information from adolescents to first allow them to think through the answers on their own (e.g., when asked how HIV was transmitted, the parent would have the adolescent think through what they already knew about HIV transmission before answering the question). By using this strategy, parents were able to see how much their children remembered from previous conversations and encourage them to share information with one other. This strategy also helped parents to gauge how well their children had mastered one topic before moving on to others.

Other examples of quizzing adolescents included going over examples of risky scenarios. Parents encouraged critical thinking about scenarios to (a) increase adolescent awareness of how risky situations might arise, and (b) get adolescents thinking about how to plan for and successfully navigate these difficult situations. Parents often initiated these conversations with questions like “What would you do if….”? As one mother noted:

[I say]…What are you going to do if you’re in the heat of the moment? You like this guy, he likes you. Yeah, you’re alone and you’re together and you guys decide this is what you’re going to do, and ‘oh’ nobody has a condom. What are you going to do? Think about it. You know, nobody knows, it’s just you and him in the heat of the moment. What are you going to do? Are you going to wait and go to the store and get a condom? Are you just going to say no? Are you going to continue to have sex?

After parents had detailed a given scenario and elicited the adolescent’s opinion on how to handle the situation, parents were able to offer suggestions that might be helpful when navigating similar situations. This gave adolescents both a “voice” (e.g., let them explain what they thought was the best course of action) and a “choice” (e.g. armed them with more than one effective strategy) with regards to sexual health and safety. Parents who gave examples of this strategy used quizzing as a gentle learning tool rather than a way to criticize adolescents’ for faulty answers.

Step #4: Checking in on child’s thoughts, feelings, or questions

Parents also expressed the importance of checking in with adolescents during conversations or HIV-related events to see if they understood the information being discussed, how they felt about the topic, and/or if they had any questions that the parent could answer. As Brie noted, it was important for her 16 year old daughter to be able to express her thoughts and feelings about what was going on with her body, particularly during puberty and adolescence.

I have her voice her opinion and keep talking because some things have got to stick. You don’t just have one-sided conversations about their body. They have to have some kind of input, you know? And I didn’t get that chance (with my mom), so I want her to have that opportunity to discuss how she feels about what’s going on with her body.

A couple of parents even asked their children what sex was like for them and if they were enjoying it. This usually led to conversations about the different reasons that people have sex and how important it is to not feel pressured to engage in sexual activity or to have sex for someone else. Overall, these parents were trying to express to their children that they (the parent) understood that adolescents faced difficult situations, that they cared about them enough to listen to their thoughts and feelings, and that it was productive to reflect on sexual experiences both prior to and after they occurred.

Step #5: Setting the stage for future conversations

Finally, parents who emphasized the effectiveness of interactive conversations often spoke of setting the stage for future prevention conversations. Bertrisa, mother of eight, noted the importance of encouraging her 13 year old son to come back and talk to her after giving him brochures and pamphlets on prevention and encouraging him to attend an educational class on HIV. As she explained:

[A good way is to say] “Here is some literature I picked up. I want you to read about it and let me know what you think about it. If you want me to go to the class with you, I’ll go with you. If you feel more comfortable going with one of your friends, [that’s okay]. But go and come back and talk to me and tell me what you think about it.”

This mother was allowing her son to process information she had given him without pressuring him to have an immediate face-to-face conversation (and giving him a choice on who he wanted to attend the educational class with). She was recognizing that there were multiple effective modalities for her son to learn, but also communicating to him that she welcomed and expected conversations between the two of them in the future. Other parents set the stage for future conversations by acknowledging what they would talk about “next time,” or by letting their children know that it was okay to think about the information they learned and come back to them later with additional questions.

Overall, parents who used interactive strategies appeared to have a great deal of practice when it came to discussing sex and HIV. These parents were often health educators, case managers, social workers, or may have been involved in research, volunteer activities, or therapy where they received training relevant to communicating about HIV-related topics. The interactive strategies parents spoke of were not meant to be used in isolation, but rather in conjunction with one another (i.e., as a series of conversational steps or components). Thus, a parent could start a simple back-and-forth exchange about sexual safety, provide a condom demonstration, quiz a child to see what they learned, check in to see if their child had questions, and set the stage for future conversations all within a given conversation or series of conversations. The exact order of the steps was viewed as less important than trying to integrate the various components into a natural and comfortable conversation tailored to one’s child.

Discussion

This report summarized five key components of interactive discussions between parents and adolescents about sexual health and HIV prevention. The advice tendered by these parents must be qualified by the reality that they were volunteers from one part of the country with its own norms and customs. Thus, the guidance offered might not be germane to other cultural settings or family structures. Additionally, all interview data is derived from parental self-report, with no independent verification from their children and no direct observation of what parents were actually doing when conversing about prevention and safer sex. Finally, given the qualitative focus of our manuscript, we cannot speak to how parent-child discussions varied by parent demographics, parental HIV disclosure status, or by child HIV status. These variables would provide interesting avenues for future study.

Nonetheless, this sample of parents is among the largest group of parents living with HIV to offer their personal experiences and guidance on how they have attempted interactive conversations with their children about a set of personally sensitive topics (Corona et al., 2009; Murphy, Roberts, & Herbeck, 2011). For some parents, the fact that any conversation about sexual health and HIV prevention occurred at all would come as a revelation. The silence surrounding sexuality that can pervade families affected by HIV/AIDS is alluded to in a study by O’Sullivan et al. (2005), who found that less than half of parents with HIV had discussed preventive topics with their 10 to 14 year old children. In addition, Marhefka et al. (2009) found that parents living with HIV and their uninfected youth were just as poor in their predictions about when youth would sexually debut as parents and youth who were HIV-. The authors speculate that, since many parents wait until adolescents appear “ready” to have sex to discuss preventive information, even parents with HIV could easily miss relaying information about sexual safety at a time of critical need. Our data suggest practical ways for parents with HIV to make these early conversations interactive. If parents and adolescents can establish ways to interactively talk about sexual health and prevention, each party will be better aware of what the other’s thoughts and values are on issues of personal protection and safety.

For parents who have attempted to initiate dialogue, the idea of doing so more than one time might also be a surprise. Anecdotally, there are a myriad of stories from adults of how their parents had “the talk,” never to bring up the subject again or to encourage recurring conversations (Authors, 2012). Parents in this study emphasized that ending preventive conversations with the understanding that the current conversation was the first of many helped adolescents to get used to the idea of future conversations. Additionally, parents viewed their children as active (and sometimes equal) conversational partners. The mindset with which parents in this sample broached preventive conversations might help other parents with HIV set the conversational tone and content of HIV-related talks.

Continuing with the notion that learning about HIV takes time, parents found that several recursive techniques were effective when discussing preventive topics. Thus, parents gently quizzed their children to see if they understood what was being talked about, as well as signaled that more dialogue would be occurring in the future. The empirical effectiveness of this approach to communication remains unknown and could be tested in future studies. However, evidence from the broader parent-adolescent sexual communication literature indicates that, compared with a traditional lecture-based approach to learning about HIV prevention, adolescents who underwent interactive training with their parents (e.g., role-playing, practicing discussions with one another) had increased knowledge about how to protect against HIV and were more likely to report that their parents had definite rules dating, contraception, and sex (Lederman, Chan, & Roberts-Gray, 2008). Thus, advice on how to conduct interactive discussions could help parents work with their children towards safe, informed, and healthier sexual relationships.

In terms of implications for support programs for parents with HIV, the advice from these parents suggests that social workers and case managers should encourage parents to be gentle, yet straightforward with their children surrounding issues of personal protection against HIV infection, and to use practical, developmentally appropriate methods to initiate and sustain dialogue. Many of the parents in our sample learned a great deal about HIV from their case managers, HIV support groups, and the medical professionals involved in their care, and had taken the time to transfer this knowledge to their children. Knowing that these parents have conversed with their adolescents about sex and HIV and have found the strategies reported here to be effective in their personal encounters could inspire other parents living with HIV/AIDS to do the same.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the parents who participated in this study, the HIV-related organizations that helped with recruitment, and the following individuals who provided assistance: Dr. Dale Brashers, Dr. Sari Aronson, Cindy Goetting, and the students in CHLH 393 and SPCM 462 who helped transcribe interviews. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

FUNDING: The research in this article was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant F30 MH086364), the Sherri Aversa Memorial Foundation Dissertation Completion Award, and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Graduate College, College of Medicine, and Department of Communication.

Footnotes

For more information on the other types of strategies parents in this sample used to discuss HIV prevention, please reference Edwards, 2012.

Contributor Information

Laura L. Edwards, Department of Kinesiology and Community Health, College of Medicine, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign

Janet S. Reis, College of Health Sciences, Boise State University

References

- Albert B. With One Voice 2004: America’s Adults & Teens Sound Off About Teen Pregnancy. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2004. Retrieved July 30, 2012 from www.teenpregnancy.org/resources/data/pdf/WOV2004.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Cowgill BO, Kennedy D, Ryan G, Murphy DA, Elijah J, Schuster MA. HIV-related stigma among people with HIV and their families: A qualitative analysis. AIDS & Behavior. 2008;12:244–254. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9231-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederbaum JA. Doctoral dissertation. 2009. The influence of maternal HIV serostatus on mother-daughter sexual risk communication and adolescent engagement in HIV risk behaviors. Retrieved from Digital Dissertations. (AAT 3381506) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parents Matter! Existing research about parental influences on teen sexual risk behaviors. 2008 Retrieved December 27th, 2008, from http://www.cdcnpin.org/ParentsMatter/research.asp.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Slide Set: HIV Surveillance in Adolescents and Young Adults (through 2010) 2012 Retrieved July 26,2012 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/adolescents/slides/Adolescents.pdf.

- Chabon B, Futterman D, Hoffman ND. HIV infection in parents of youth with behavioral acquired HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;9:649–650. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Corona R, Cowgill BO, Bogart LM, Parra MT, Ryan G, Elliott MN, Schuster MA. A qualitative analysis of discussions about HIV in families of parents with HIV. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(6):677–680. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Wingood GM. HIV prevention for adolescents: Identified gaps and emerging approaches. Prospects. 2002;32(2):135–153. [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, McCarty F, Pluhar E. Talking about HIV and AIDS: A focus of parent-child discussions. In: Edgar T, Noar SM, Freimuth VS, editors. Communication Perspectives on HIV/AIDS for the 21st Century. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. pp. 169–192. [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Pluhar E, Belcher L. Parent-child communication about sexuality: A review of the literature from 1980–2002. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents & Children. 2003;5(3/4):7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dittus PJ, Jaccard J. Adolescents’ perceptions of maternal disapproval of sex: Relationship to sexual outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26(4):268–278. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittus PJ, Jaccard J, Gordon VV. Direct and non-direct communication of maternal beliefs to adolescents: Adolescent motivation for premarital sexual activity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1999;29:1927–1963. [Google Scholar]

- Dittus P, Miller KS, Kotchick BA, Forehand R. Why Parents Matter! The conceptual basis for a community-based HIV prevention program for the parents of African American youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2004;13(1):5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dutra R, Miller KS, Forehand R. The process and content of sexual communication with adolescents in two-parent families: Associations with sexual risk-taking behavior. AIDS & Behavior. 1999;3:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LL. Doctoral dissertation. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; 2012. HIV prevention communication in families affected by HIV/AIDS. Retrieved from https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/34222. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith DJ, Bute JJ, Lindholm KA. Patient and partner strategies for talking about lifestyle change following a cardiac event. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2011;40(1):65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2009 Survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS: Summary of Findings on the Domestic Epidemic. 2009 Retrieved July 28, 2012 from http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/7889.cfm.

- Kosenko KA. Meanings and dilemmas of sexual safety and communication for transgender individuals. Health Communication. 2010;25(2):131–141. doi: 10.1080/10410230903544928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederman RP, Chan W, Roberts-Gray C. Parent-adolescent relationship education (PARE): Program delivery to reduce risks for adolescent pregnancy and STDs. Behavioral Medicine. 2008;33:137–143. doi: 10.3200/BMED.33.4.137-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MB, Lester P, Rotheram-Borus MJ. The relationship between adjustment of mothers with HIV and their adolescent daughters. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2002;7(1):71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz ES, Sigman M, Au TK. Helping mothers discuss sexuality and AIDS with adolescents. Child Development. 2000;71(5):1383–1394. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr ST, DiIorio C, Dudley WN, Lipana JA. The relationship between parent-adolescent communication and safer sex behavior in college students. Journal of Family Nursing. 2000;6(2):180–197. [Google Scholar]

- Leland NL, Barth RP. Characteristics of adolescents who have attempted to avoid HIV and who have communicated with their parents about sex. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1993;8:58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard NR, Gwadz MV, Cleland CM, Vekaria PC, Ferns B. Maternal substance use and HIV status: adolescent risk and resilience. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31(3):389–405. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein B, Sturdevant MS, Mujumdar AA. Psychosocial stressors of families affected by HIV/AIDS: Implications for social work practice. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. 2010;9(2):130–152. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods. 1998;10(2):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Manlove J, Ikramulla E, Terry-Humen E. Condom use and consistency among male adolescents in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43(4):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhefka SL, Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Ehrhardt AA. Perceptions of adolescents’ sexual behavior among mothers living with and without HIV: Does dyadic sex communication matter? Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38(5):788–801. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9284-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May S, Lester P, Ilardi BA, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Childbearing among daughters of parents with HIV. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2006;30(1):72–84. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2006.30.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Dolezal C, Brackis-Cott E, Nicholson O, Warne P, Meyer-Bahlburg HF. Predicting the onset of sexual and drug risk behaviors in HIV-negative youths with HIV-positive mothers: the role of contextual, self-regulation, and social-interaction factors. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2007;36(3):265–278. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Fasula AM, Dittus P, Wiegand RE, Wyckoff SC, McNair L. Barriers and facilitators to maternal communication with preadolescents about age-relevant sexual topics. AIDS & Behavior. 2009;13(2):365–374. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA. HIV-positive mothers’ disclosure of their serostatus to their young children: A review. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2008;13(1):105–122. doi: 10.1177/1359104507087464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Herbeck DM, Marelich WD, Schuster MA. Predictors of sexual behavior among early and middle adolescents affected by maternal HIV. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2010;22(3):195–204. doi: 10.1080/19317611003800614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Roberts KJ, Herbeck DM. HIV-Positive mothers’ communication about safer sex and STD prevention with their children. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33(2):136–157. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11412158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Dolezal C, Brackis-Cott E, Traeger L, Mellins CA. Communication about HIV and risk behaviors among mothers living with HIV and their early adolescent children. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25(2):148–167. [Google Scholar]

- Pick S, Palos PA. Impact of the family on the sex lives of adolescents. Adolescence. 1995;30(119):667–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. Estimated HIV Incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesch SK, Anderson LS, Krueger HA. Parent-child communication processes: Preventing children’s health risk behavior. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses. 2006;11(1):41–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2006.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneed CD. Parent-adolescent communication about sex: The impact of content and comfort on adolescent sexual behavior. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children & Youth. 2008;9(1):70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E, Magilvy JK. Qualitative rigor or research validity in qualitative research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2011;16:151–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2011.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley BJ, Lees NB, Sumartojo E. Child and adolescent HIV risk: Familial and cultural perspectives. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(1):208–224. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Miller KS, May DC, Levin ML. Teenage partners’ communication about sexual risk and condom use: Importance of parent-teenager communication. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31:117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]