Abstract

Although extant research demonstrates that body valuation by strangers has negative implications for women, Studies 1 and 2 demonstrate that body valuation by a committed male partner is positively associated with women’s relationship satisfaction when that partner also values them for their non-physical qualities, but negatively associated with women’s relationship satisfaction when that partner is not committed or does not value them for their non-physical qualities. Study 3 demonstrates that body valuation by a committed female partner is negatively associated with men’s relationship satisfaction when that partner does not also value them for their non-physical qualities but unassociated with men’s satisfaction otherwise. These findings join others demonstrating that fully understanding the implications of interpersonal processes requires considering the interpersonal context. (120 words)

Keywords: intimate relationships, marriage, commitment, women, objectification

Men frequently value women for the appearance of their bodies. For example, men frequently stare at women’s bodies (Kozee, Tylka, Augustus-Horvath, & Denchik, 2007; Quinn, 2002), make comments and gestures to women about their bodies (Kozee et al., 2007; Swim, Hyers, Cohen, & Ferguson, 2001), and even reduce women to being nothing more than their body (Gervais, Vescio, & Allen, 2011). What are the implications of such body valuation for women?

Previous research suggests that the consequences for women of being valued for their bodies are mostly negative. Specifically, research in support of objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) demonstrates that women who are valued for their bodies and body parts tend to view themselves as sexual objects rather than complete human beings (Bartky, 1990; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) and thus experience decreased well-being (Aubrey, 2006; Fredrickson, Roberts, Noll, Quinn, & Twenge, 1998; Liss, Erchull, & Ramsey, 2011; Szymanski & Henning, 2007; Tiggemann, 2001). For example, women who either anticipate being looked at by a man (Calogero, 2004) or report being the target of men’s cat-calls and whistles (Fairchild & Rudman, 2008) report increased levels of anxiety. In fact, merely reminding women that men value them for their bodies (e.g., exposing women to images of sexualized women, asking women to try on a swimsuit) decreases self-esteem and increases disordered eating (Aubrey, 2006; Fredrickson et al., 1998; Tiggemann, 2001).

Partner’s Body Valuation and Women’s Satisfaction with Their Intimate Relationships

Nevertheless, virtually all that work has examined the implications of women’s experiences of being valued for their bodies in the context of broad, societal messages or in interactions with male strangers (for an exception, see Zurbriggen, Ramsey, & Jaworski, 2011). Yet, women are not only valued for their bodies in such non-intimate contexts—they are also valued for their bodies in their intimate relationships (Chen & Brown, 2005; Fletcher, Simpson, Thomas, & Giles, 1999; Kurzban & Weeden, 2005; Legenbauer et al., 2009; Zurbriggen et al., 2011). Are women’s experiences of being valued for their body by an intimate partner also mostly negative? Or, given that such physical attraction is a defining feature of intimate relationships, does body valuation have more beneficial implications for women in the context of their intimate relationships?

At least one line of research suggests women should be more satisfied with their relationships to the extent that they are valued for their bodies by their intimate partner. A robust literature demonstrates that people are happier in their intimate relationships when they meet their partners’ ideals and standards (Campbell, Simpson, Kashy, & Fletcher, 2001; Langis, Sabourin, Lussier, & Mathieu, 1994; Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 1996; Rusbult, Kumashiro, Kubacka, & Finkel, 2009). And it is particularly important to men that their female partner has an attractive body (Chen & Brown, 2005; Fletcher et al., 1999; Harris, Harris, & Bochner, 1982; Kurzban & Weeden, 2005; Legenbauer et al., 2009). For example, men’s preference for a partner with an attractive body is so strong that men report preferring a woman with either a history of psychological disturbance or a history of a sexually transmitted disease to an obese woman (Chen & Brown, 2005). Given that people tend to be more satisfied when they meet such partner preferences, women may be more satisfied with their relationships to the extent that their male partner values them for their body.

Empirical research is consistent with this idea. Body thinness accounts for nearly 75% of the variance in women’s body attractiveness (Tovée, Maisey, Emery, & Cornelissen, 1999), and consistent with the idea that women should be more satisfied in their relationships to the extent that they meet their male partners’ standard that they have attractive bodies, several studies indicate that relatively thin women report higher relationship satisfaction than do relatively larger women (Boyes & Latner, 2009; Meltzer & McNulty, 2010; Sheets & Ajmere, 2005). Nevertheless, none of those studies demonstrated that the association between women’s thinness and their relationship satisfaction emerged because male partners valued those women for their bodies. To demonstrate such an association, research would need to directly measure the extent to which women believe their male partner values them for their body and demonstrate an association between that variable and those women’s relationship satisfaction.

The Moderating Role of Partners’ Non-Physical Valuation

But if women should be more satisfied with their relationships when their partners value them for their bodies because such valuation indicates they are meeting an important relationship standard, why don’t women who are valued by strangers experience similar benefits? After all, just as male partners hold women to the standard of having an attractive body, society holds women to the norm of having an attractive body (Cusumano & Thompson, 1997). And just as people are more satisfied when they meet a partner’s standards, people are more satisfied when they meet societal norms (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Cialdini & Trost, 1998; Levine, 1980). Accordingly, women who are valued for their bodies by strangers should also experience higher levels of satisfaction. But, as described earlier, a robust body of research indicates that women who are valued for their bodies by strangers experience more negative outcomes.

An important difference between women’s experience of body valuation by male strangers and their experience of body valuation by a male partner may explain the discrepancy between this body of research and the predicted findings—women who are valued for their bodies by strangers tend to be valued only for their bodies; strangers do not typically have access to information about a woman’s non-physical qualities and thus female targets of body valuation by a male stranger must assume they are not also valued for their non-physical qualities. Accordingly, it makes sense that women who are valued for their bodies by male strangers feel like mere sexual objects and thus experience undesirable emotions. An intimate partner, in contrast, has in-depth knowledge of a woman’s non-physical qualities. And a robust body of research indicates that, in addition to desiring women with nice bodies, men desire women who are, among other things, loyal, kind, successful, fun, trustworthy, sensitive, supportive, and humorous (Baucom, Epstein, Rankin, & Burnett, 1996; Fletcher & Simpson, 2000; Fletcher et al., 1999; Hassebrauck, 1997). Thus, to the extent that male partners value women for their bodies and for these non-physical qualities, women should feel the most satisfied—because they are meeting their partners’ physical and non-physical standards. In contrast, just like women who are valued for their bodies by strangers, women who are valued for their bodies but not valued for their non-physical qualities by an intimate partner may feel like mere sexual objects and thus be dissatisfied with their relationship. In other words, whereas body valuation may be positively associated with relationship satisfaction among women who are also valued for their non-physical qualities, body valuation may be negatively associated with relationship satisfaction among women who are not also valued for their non-physical qualities.

The Moderating Role of Perceived Commitment

Of course, there is more to a long-term, intimate relationship than being valued for one’s physical and non-physical qualities—long-term relationships are also defined by commitment. Accordingly, just like women who are valued for their bodies by strangers and partners who do not value them for their non-physical qualities, women who are valued for their bodies by uncommitted partners may feel like mere sexual objects and thus be less satisfied with their relationships. Accordingly, although body valuation by a committed male partner who also values non-physical qualities should be positively associated with women’s relationship satisfaction, body valuation by an uncommitted male partner may be negatively associated with satisfaction regardless of whether that partner also values the woman for her non-physical qualities.

Although we are aware of no studies that have tested this possibility directly, commitment to the relationship has been shown to moderate the link between other factors and women’s relationship outcomes (Amodio & Showers, 2005; Frye, McNulty, & Karney, 2008; Miller & Maner, 2010). For example, whereas perceived partner similarity is positively associated with relationship satisfaction among women in more committed relationships, perceived partner similarity is negatively associated with relationship satisfaction among women in less committed relationships (Amodio & Showers, 2005). Commitment may similarly determine the extent to which body and non-physical valuation by an intimate partner interact to predict women’s relationship satisfaction.

We are aware of only one study that has examined the effects of partner body valuation in intimate relationships. Zurbriggen and colleagues (2011) demonstrated that women’s reports of increased perceived partner objectification were negatively associated with relationship satisfaction. Nevertheless, non-physical valuation and commitment were not assessed in that study. Given the theoretical analyses described above, the main effect of body valuation may mask important associations, such as the positive association between body valuation and relationship satisfaction among women who are (a) also valued for their non-physical qualities and (b) perceive their relationship to be characterized by commitment.

Overview of the Current Studies

We conducted three studies to examine the role of a partner’s body valuation in intimate relationships. In the first study, women in dating relationships reported the extent to which they believed their male partner valued them for their body and non-physical qualities, the extent to which they believed that partner was committed, and their relationship satisfaction. In the second study, recently-married husbands reported the extent to which they valued their wives for their bodies and non-physical qualities and their wives reported the extent to which they perceived their marriages were characterized by commitment and their relationship satisfaction. Finally, in the third study, we examined the effects of men’s perceptions of body valuation from a female partner. Specifically, men in dating relationships reported the extent to which they believed that their female partner valued them for their body and non-physical qualities, the extent to which they believed that partner was committed, and their relationship satisfaction.

In Studies 1 and 2, we predicted that body valuation by a male partner would be positively associated with relationship satisfaction among women whose partner also valued them for their non-physical qualities and was committed, but negatively associated with satisfaction among women whose partner did not also value them for their non-physical qualities or was not committed. In Study 3, we made no strong predictions regarding how body valuation by a female partner would predict men’s relationship satisfaction.

Study 1

Heterosexual women in a dating relationship that had been ongoing for at least 1 month completed measures online in which they reported the extent to which they believed that their partner valued them for their body and non-physical qualities, the extent to which they believed that their partner was committed to a long-term relationship, and their relationship satisfaction. Analyses examined whether women’s perceptions of their partners’ (a) tendencies to value those women for their non-physical qualities and (b) commitment moderated the effects of those partners’ tendencies to value those women for their bodies on women’s relationship satisfaction.

Method

Participants

Participants were 108 heterosexual women who were currently involved in a dating relationship that had been ongoing for at least 1 month (M = 16.1 months, SD = 15.6). Participants reported a mean age of 18.67 (SD = 1.17); most were first year undergraduates (65.7%), and most (84.3%) identified as Caucasian (11.1% identified as African American, 0.9% identified as Native American, 0.9% identified as Asian American, 0.9% identified as Hispanic or Latina, and 1.9% identified as an ‘other’ race). All participants received partial fulfillment of a course requirement in exchange for their participation.

Procedure and measures

After signing up for the study through the University’s online research system, participants read and signed a consent form approved by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB). Then, all participants completed a measure of (a) the extent to which they perceived that their relationship partner valued them for their body and their non-physical qualities, (b) the extent to which they perceived that their partner was committed to a long-term relationship with them, and (c) relationship satisfaction.

Body valuation

In the absence of any existing measures of the extent to which relationship partners value one another for their bodies, we developed a 1-item measure that was high in face validity. Specifically, we asked participants to answer the following question: “How much do you think your boyfriend values you for your body?,” where 0 = not at all and 100 = completely. A pilot study of 55 undergraduate women validated this one-item measure by demonstrating that participants interpreted this item as asking the extent to which their partner values them for their body because it is attractive to look at and/or available for sex, rather than because it is available for comfort/cuddling/warmth or capable of engaging in non-sexual activities.

Non-physical valuation

We also developed a measure to assess the extent to which women perceive that their partners value them for various non-physical qualities shown to be important to men (e.g., Fletcher et al., 1999). Specifically, participants indicated the extent to which they believed their partners valued them for their intelligence, fun, creativity, ambition, kindness, generosity, patience, career success, trustworthiness, ability to solve problems, humor, loyalty, and supportiveness, where 0 = not at all and 100 = completely. Responses were averaged to form an index of the extent to which men valued women for their non-physical qualities. Internal consistency was high (Chronbach’s α = .94).

Commitment to a long-term relationship

We also developed a 1-item measure to assess the extent to which women perceived that their partners were committed to a long-term relationship. Specifically, we asked participants to answer the following question: “What kind of relationship do you think this is for your partner?” where 0 = completely short-term relationship and 100 = completely long-term relationship.

Relationship satisfaction

We assessed global relationship satisfaction using a version of the Semantic Differential (SMD; Osgood, Suci, & Tannenbaum, 1957). On this version of the SMD, participants evaluated their relationship according to 15 sets of opposing adjectives (e.g., good-bad, satisfying-unsatisfying) on a 7-point scale. Thus, scores ranged from 15 to 105, with higher scores indicating greater relationship satisfaction. Internal consistency was high (Chronbach’s α = .91).

Covariates

Given that prior research demonstrated thinner women sometimes report higher levels of relationship satisfaction (Boyes & Latner, 2009; Meltzer & McNulty, 2010; Sheets & Ajmere, 2005), and given that women’s body size may be associated with men’s body valuation, we assessed women’s body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), based on their self-reported height and weight. Supporting the validity of this measure, a meta-analysis demonstrates that self-reported height and weight provide an accurate indicator of actual BMI (Bowman & DeLucia, 1992). Additionally, we controlled for participants’ age and relationship length, after it had been log transformed.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. A few of these are worth highlighting. First, participants reported relatively high levels of relationship satisfaction and high confidence that their partners were committed to a long-term relationship, on average. Nevertheless, there was substantial variability in both reports. Second, participants’ mean BMI was in the normal weight range as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2009). Third, women perceived body and non-physical valuation from their partners, on average. Nevertheless, there was substantial variability in those reports as well. Notably, women perceived less body valuation than non-physical valuation from their partners (t(107) = −2.26, p < .01, Cohen’s d = 0.44). Fourth, not surprisingly, perceived partner commitment was positively associated with relationship satisfaction. Fifth, the extent to which women perceived that their partners valued them for their bodies was significantly positively associated with the extent to which women perceived that their partners valued them for their non-physical qualities. Finally, whereas the extent to which women perceived that their partners valued them for their non-physical qualities was significantly associated with perceived relationship commitment and relationship satisfaction, the extent to which women perceived that their partner valued them for their bodies was not associated with either variable, on average.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study 1.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Body Valuation | -- | ||||

| (2) Non-Physical Valuation | .36*** | -- | |||

| (3) Commitment | .06 | .22* | -- | ||

| (4) Relationship Satisfaction | .06 | .33*** | .38*** | -- | |

| (5) BMI | −.10 | −.16 | −.02 | −.12 | -- |

|

| |||||

| M | 74.40 | 79.86 | 84.60 | 93.16 | 23.20 |

| SD | 25.34 | 18.05 | 20.37 | 15.81 | 4.70 |

Note. N = 108.

p < .05.

p < .001.

To test our prediction that the association between perceived body valuation and relationship satisfaction depends on perceived (a) non-physical valuation and (b) partner commitment, we regressed women’s relationship satisfaction onto the standardized score of perceived body valuation, the standardized score of perceived non-physical valuation, the standardized score of perceived partner commitment, and all possible interactions. Results are reported in Table 2. As can be seen there, perceived non-physical valuation and perceived partner commitment were positively associated with relationship satisfaction, and the Body Valuation × Partner Commitment interaction was positively associated with relationship satisfaction. Nevertheless, as predicted, those main effects and that 2-way interaction were qualified by the significant positive Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation × Partner Commitment interaction. Notably, this effect remained significant controlling for participants’ BMI, age, and the log of relationship length (B = 2.11, SE = 1.05, t(90) = 2.02, p = .047).

Table 2. Study 1—Associations between Women’s Perceived Partner Body Valuation, Perceived Non- Physical Valuation, Perceived Commitment, Their Interactions, and Women’s Relationship Satisfaction.

| Relationship Satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE |

Effect Size

r |

|

| Intercept | 92.32 | 1.42 | -- |

| Body Valuation (B) | −0.46 | 1.51 | .03 |

| Non-Physical Valuation (NP) | 4.34 | 1.72 | .24* |

| Partner Commitment (C) | 5.02 | 1.55 | .31** |

| B × NP | 0.54 | 0.88 | .06 |

| B × C | 3.35 | 1.40 | .23* |

| NP × C | 0.40 | 1.39 | .03 |

| B × NP × C | 2.12 | 0.85 | .24* |

Note. dfs = 100. Effect size .

p < .05.

p < .01.

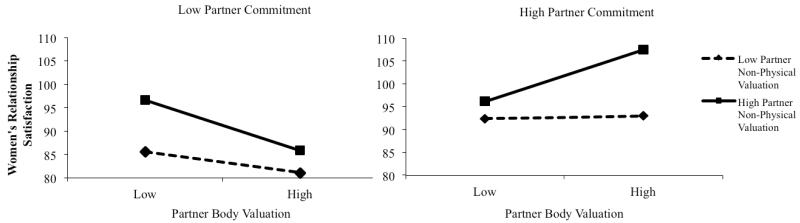

To view the nature of that 3-way interaction, we decomposed it by plotting the predicted means for individuals 1 SD above and below the mean on each variable involved in the interaction. That plot is depicted in Figure 1. As can be seen, and as predicted, the direction in which perceived body valuation was associated with relationship satisfaction depended on whether women also perceived that their partner (a) valued them for their non-physical qualities and (b) was committed.

Figure 1.

Study 1—Interactive Effects of Perceived Partner Valuation for Body, Perceived Partner Valuation for Non-Physical Qualities, and Perceived Partner Commitment on Women’s Relationship Satisfaction

To determine the simple effects of body valuation, we first tested the statistical significance of each simple Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation interaction among women high versus low on perceived commitment. Among women who perceived that their partner was 1 SD less committed than the mean, the Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation interaction was not significant (B = −1.59, SE = 1.27, t(100) = −1.25, ns). Instead, as predicted, body valuation by an uncommitted partner was marginally negatively associated with relationship satisfaction regardless of the extent to which that partner valued them for their non-physical qualities (B = −3.81, SE = 1.96, t(100) = −1.94, p = .055). Among women who perceived that their partners were 1 SD more committed than the mean, in contrast, the Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation interaction was significant (B = 2.66, SE = 1.18, t(100) = 2.26, p = .026). Breaking down that interaction revealed that whereas body valuation by a committed partner was not significantly associated with relationship satisfaction among women who perceived their partner valued them for their non-physical qualities 1 SD less than the mean (B = 0.23, SE = 2.20, t(100) = 0.10, ns), consistent with predictions, body valuation by a committed partner was significantly positively associated with relationship satisfaction among women who perceived their partner valued them for their non-physical qualities 1 SD more than the mean (B = 5.54, SE = 2.70, t(100) = 2.05, p = .043).

Discussion

Study 1 provided preliminary evidence that the association between the extent to which an intimate partner values a woman for her body and that woman’s relationship satisfaction depends on the extent to which that partner (a) also values that woman for her non-physical qualities and (b) is committed to a long-term relationship. As predicted, the extent to which women perceived that their partner valued them for their body was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction among women who perceived that their partner was relatively less committed, regardless of the extent to which that partner valued them for their non-physical qualities. However, also consistent with predictions, the association between body valuation by a committed partner and women’s relationship satisfaction depended on the extent to which they perceived that their partner also valued them for their non-physical qualities. Whereas perceived partner body valuation was not associated with relationship satisfaction among women who perceived that their committed partner did not value them for their non-physical qualities, perceived partner valuation was positively associated with relationship satisfaction among women who perceived that their committed partner did value them for their non-physical qualities. Notably, these effects held controlling for women’s BMI, age, and relationship length.

Nevertheless, Study 1 was limited in two important ways. First, our sample was comprised of college-aged women in dating relationships, women with partners likely to be less committed than people in more established long-term relationships like marriage. Thus, it remains unclear whether the effects generalize to such relationships. Second, in Study 1 we assessed the extent to which women perceived that their partners valued them for their body and non-physical qualities rather than their partners’ actual levels of such valuation. Thus, it remains possible that some quality common to women who perceive different levels of body valuation, non-physical valuation, and commitment accounts for the results that emerged in Study 1.

Study 2

Study 2 addressed both of these limitations. First, helping to ensure that the effects in Study 1 were not unique to samples of relatively less committed couples, Study 2 used a sample of married couples. Second, Study 2 more directly assessed the role of partner body and non-physical valuation for women’s relationship satisfaction by measuring husbands’ reports of the extent to which they valued their wives for their body and non-physical qualities.

Method

Participants

Participants were 69 recently-married couples who had completed the relevant measures in the fifth wave of data collection in a broader multiwave, longitudinal study of 135 newlywed couples (for details regarding the larger dataset, see Baker & McNulty, 2010, 2011; Baker, McNulty, Overall, Lambert, & Fincham, in press; McNulty, 2010; McNulty & Russell, 2010; Meltzer & McNulty, 2010). We used data from this wave because it was the first to include all relevant measures. The couples not included in the current analyses had either (a) divorced (n = 12, 9%), (b) dropped from the study (n = 10, 7%), (c) been widowed (n = 1, 1%), or (d) did not complete all measures during the fifth phase of data collection (n = 43, 31%). Participants were recruited through advertisements placed in community newspapers and bridal shops and through invitations sent to eligible couples who had applied for marriage licenses in counties near the study location. Couples who responded were screened in a telephone interview to ensure they met the following criteria: (a) they had been married for less than 6 months, (b) neither partner had been previously married, (c) they were at least 18 years of age, (d) they spoke English and had completed at least 10 years of education (to ensure questionnaire comprehension), and (e) did not yet have children (as part of the broader aims of the study).

At their baseline assessment (approximately two years earlier), the husbands were 25.83 years old (SD = 4.21) and had completed 16.29 years of education (SD = 2.40), on average. Seventy percent were employed full time and 28% were full-time students. The wives were 23.87 years old (SD = 3.39) and had completed 18.87 years of education (SD = 2.15), on average. Fifty-two percent were employed full time and 30% were full-time students. Sixty-one (88%) husbands and 64 (93%) wives identified as Caucasian. These couples did not differ from the participants who did not complete the relevant measures at this phase of the study on any of these variables, with the exception that these husbands were more educated at baseline (t(133) = 2.52, p = .013, Cohen’s d = 0.44) and these wives earned less money at baseline (χ2(10) = 19.00, p = .040).

Procedure and measures

At the fifth wave of data collection, couples were contacted by phone or email and mailed 2 packets of questionnaires (one for each spouse). Husbands’ packets contained measures of partner body valuation and non-physical valuation. Wives’ packets contained measures of perceived commitment and relationship satisfaction. Both packets included a postage-paid return envelope and an instruction letter reminding couples to complete the questionnaires separately from one another. Couples were paid $50 for completing these questionnaires.

Body valuation

Whereas women in Study 1 reported their perceptions of their partners’ tendencies to value them for their bodies, the husbands in the current study reported on their own tendencies to value their wives for their bodies by answering the following question: “How much do you value your wife for her body?,” where 0 = not at all and 100 = completely.

Non-physical valuation

Whereas women in Study 1 reported their perceptions of their partners’ tendencies to value them for their non-physical qualities, the husbands in the current study reported on their own tendencies to value their wives for the same 13 non-physical qualities assessed in Study 1, where 0 = not at all and 100 = completely. Internal consistency was adequate (Chronbach’s α = .83).

Commitment

Wives reported their perceptions of the extent to which their relationship was characterized by commitment by answering the following question: “Over the next six months, to what extent do you expect your relationship to be characterized by commitment?,” where 1 = not at all and 7 = completely1.

Relationship satisfaction

We assessed wives’ global relationship satisfaction using the Quality Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, 1983). Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with 6 general statements regarding the quality of their marriage. Whereas participants responded to 5 items according to a 7-point scale, they responded to 1 item according to a 10-point scale. Thus, scores ranged from 6 to 45, where higher scores reflect more positive satisfaction with the relationship. Internal consistency was high (Chronbach’s α = .95).

Covariates

We assessed wives’ BMI, derived from self-reported height and weight. Additionally, we controlled for wives’ age.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 3. A few of these are worth highlighting. First, wives reported relatively high relationship commitment and satisfaction, and husbands valued their wives for their bodies and non-physical qualities, on average. Nevertheless, there was substantial variability in those reports. Notably, unlike what was found in Study 1, the extent to which husbands valued their wives for their bodies did not differ from the extent to which they valued their wives for their non-physical attributes (t(69) = −1.05, ns, Cohen’s d = 0.25). Second, wives’ mean BMI was in the normal weight range (see CDC, 2009). Third, consistent with what was found in Study 1, wives’ perceptions of commitment were positively associated with their marital satisfaction, the extent to which husbands valued their wives for their bodies was positively associated with the extent to which they valued their wives for their non-physical qualities, and the extent to which husbands valued their wives for their bodies was not associated with wives’ satisfaction, on average. Finally, unlike what was found in Study 1, wives’ BMI was negatively associated with husbands’ tendencies to value those wives for their bodies.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study 2.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Husbands’ Body Valuation | -- | ||||

| (2) Husbands’ Non-Physical Valuation | .59*** | -- | |||

| (3) Wives’ Perceived Commitment | .11 | .18 | -- | ||

| (4) Wives’ Relationship Satisfaction | −.01 | .07 | .63*** | -- | |

| (5) Wives’ BMI | −.34** | −.20 | −.46*** | −.16 | -- |

|

| |||||

| M | 82.43 | 84.36 | 6.76 | 39.64 | 24.78 |

| SD | 19.18 | 10.60 | 0.65 | 6.13 | 6.10 |

Note. N = 69.

p < .01.

p < .001.

To test our prediction that the association between husbands’ body valuation and wives’ marital satisfaction would be moderated by (a) husbands’ non-physical valuation and (b) wives’ perceived commitment, we regressed wives’ marital satisfaction onto the standardized score of husbands’ body valuation, the standardized score of husbands’ non-physical valuation, the standardized score of wives’ perceived commitment, and all possible interactions. Results are reported in Table 4. As can be seen, wives’ perceived commitment was positively associated with wives’ marital satisfaction and the Body Valuation × Commitment interaction was positively associated with wives’ marital satisfaction. Nevertheless, consistent with predictions and the findings of Study 1, that main effect and 2-way interaction were qualified by a significant positive Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation × Commitment interaction. Notably, this effect remained significant controlling for wives’ BMI and age (B = 2.30, SE = 0.70, t(59) = 3.28, p = .002).

Table 4. Study 2—Associations between Husbands’ Body Valuation, Husbands’ Non-Physical Valuation, Wives’ Perceived Commitment, Their Interactions, and Wives’ Marital Satisfaction.

| Marital Satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE |

Effect Size

r |

|

| Intercept | 39.65 | 0.57 | -- |

| Husbands’ Body Valuation (B) | −1.15 | 0.75 | .19 |

| Husbands’ Non-Physical Valuation (NP) | −0.03 | 0.62 | .01 |

| Wives’ Perceived Commitment (C) | 4.84 | 0.68 | .67*** |

| B × NP | −0.57 | 0.46 | .16 |

| B × C | 4.64 | 0.86 | .56*** |

| NP × C | −0.55 | 0.80 | .09 |

| B × NP × C | 2.15 | 0.68 | .37** |

Note. dfs = 62. Effect size .

p < .01.

p < .001.

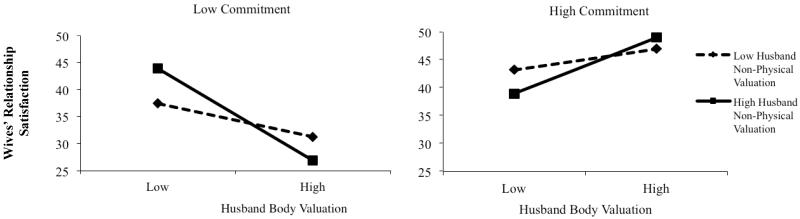

To view the nature of that 3-way interaction, we decomposed it by plotting the predicted means for individuals 1 SD above and below the mean on each variable involved in the interaction. That plot is depicted in Figure 2. A quick comparison between this plot and the plot depicted in Figure 1 may leave the viewer with the impression that the observed patterns are different. However, that noticeable difference is because of an unpredicted and irrelevant difference between the effects that emerged in Study 1 and Study 2—whereas women’s perceptions of their partner’s valuation of their non-physical qualities was positively associated with their relationship satisfaction in Study 1, husbands’ valuation of their wives’ non-physical qualities was unrelated to wives’ marital satisfaction in Study 2. In fact, that difference aside, the hypothesis-relevant effects depicted in Figure 2 are remarkably similar to those depicted in Figure 1. Specifically, consistent with predictions and the findings of Study 1, the direction in which husbands valued their wives for their bodies was associated with wives’ relationship satisfaction depended on (a) the extent to which husbands valued their wives for their non-physical qualities and (b) the extent to which women perceived that their marriages were characterized by commitment.

Figure 2.

Study 2—Interactive Effects of Husbands’ Valuation for Body, Husbands’ Valuation for Non-Physical Qualities, and Wives’ Perceived Commitment on Wives’ Martial Satisfaction

To estimate the statistical significance of these simple effects of body valuation, we first tested the statistical significance of each simple Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation interaction among women high versus low on perceived commitment. This time, a significant negative Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation interaction emerged among women who perceived that their partner was 1 SD less committed than the mean (B = −2.72, SE = 0.88, t(62) = −3.10, p = .003). Somewhat surprisingly, this negative interaction emerged because body valuation was more negatively associated with satisfaction among women who perceived that their relatively uncommitted husbands valued them for their non-physical qualities than it was among women who perceived that their relatively uncommitted husbands did not value them for their non-physical qualities. Nevertheless, as predicted, simple slopes analyses revealed that relatively uncommitted husbands’ body valuation was significantly negatively associated with wives’ relationship satisfaction regardless of whether they valued their wives for their non-physical qualities (for high non-physical valuation, B = −8.50, SE = 1.95, t(62) = −4.36, p < .001; for low non-physical-valuation, B = −3.07, SE = 0.88, t(62) = −3.51, p = .001). In contrast, but consistent with predictions and the findings of Study 1, a significant positive Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation interaction emerged among women who perceived that their partners were 1 SD more committed than the mean (B = 1.58, SE = 0.76, t(62) = 2.07, p = .043). Simple slopes analyses revealed that husbands’ body valuation was positively associated with marital satisfaction among wives with relatively committed husbands who valued them for their non-physical qualities 1 SD less than the mean (B = 1.90, SE = 0.92, t(62) = 2.06, p = .043), and positively associated with relationship satisfaction among wives with relatively committed husbands who valued them for their non-physical qualities 1 SD more than the mean (B = 5.06, SE = 1.58, t(62) = 3.20, p = .002).

Notably, the simple association between husbands’ body valuation and wives’ marital satisfaction among women with committed husbands who reported low levels of non-physical valuation may have been significant here, but not in Study 1, because even the husbands who reported valuing their wives for their non-physical qualities 1 SD below the mean in the current study reported relatively high valuation of their wives’ non-physical qualities. Specifically, whereas the value of low non-physical valuation at which this simple effect was tested in Study 2 was 73.76, the value of low non-physical valuation at which this simple effect was tested in Study 1 was 61.81. Indeed, when we tested the simple association between committed husbands’ body valuation and wives’ satisfaction at the 61.81 value of non-physical valuation used in Study 1, it was not close to significant (B = 0.13, SE = 1.41, t(62) = 0.09, ns).

Discussion

Consistent with predictions and the findings of Study 1, Study 2 demonstrated that the association between the extent to which a husband values his wife for her body and that wife’s relationship satisfaction depends on the extent to which (a) that husband also values that wife for her non-physical qualities and (b) that wife perceives their marriage to be characterized by commitment. As predicted, wives with less committed husbands who valued them for their bodies were less satisfied with their marriages regardless of the extent to which those husbands also valued those wives for their non-physical qualities. Also consistent with predictions, wives with more committed husbands who valued them for their bodies were more satisfied with their marriages to the extent that their husbands also valued them for their non-physical qualities. Notably, these effects held controlling for wives’ BMI and age.

Study 3

Although Studies 1 and 2 provide important information regarding the implications of male valuation of a female partner’s body for that partner’s satisfaction with the relationship, they raise curiosity regarding the effects of female valuation of a male partner’s body. Several possibilities make sense theoretically. Although women may be more likely to be valued for their appearance by society than are men (Bartky, 1990; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), some evidence suggests that physical appearance is equally important to men and women (Eastwick & Finkel, 2008; Fletcher et al., 1999). For instance, men and women do not differ in their tendency to list “attractiveness” and/or “nice body” as an important characteristic of an intimate partner (Fletcher et al., 1999). Accordingly, like women, men may enjoy higher levels of relationship satisfaction to the extent that a committed female partner values them for their body and their non-physical qualities. However, other evidence that has more specifically addressed body attractiveness suggests it may be less important to women than it is to men (Meltzer, McNulty, Novak, Butler, & Karney, 2011; Regan, Levin, Sprecher, Christopher, & Cate, 2000) and thus men may be held to less strict standards of body attractiveness in long-term relationships than are women. Accordingly, men may be more concerned with the extent to which they are valued for their non-physical qualities and thus less affected by the extent to which they are valued for their bodies by a committed partner. Finally, given that men demonstrate a greater interest in short-term relationships than do women (Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Thornhill & Gangestad, 2008; but see Pedersen, Miller, Putcha-Bhagavatula, & Yang, 2002), the implications of the extent to which men are valued for their bodies may not depend on commitment.

Study 3 examined the implications of body valuation for men’s relationship satisfaction. Specifically, heterosexual men in a dating relationship that had been ongoing for at least 1 month completed an online study in which they reported the extent to which they believed that their partner valued them for their body and for their non-physical qualities, the extent to which they believed that their partner was committed, and their relationship satisfaction. Analyses examined whether men’s perceptions of their partner’s (a) tendencies to value them for their non-physical qualities and (b) commitment moderated the effects of their partners’ tendencies to value them men for their bodies on their relationship satisfaction.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 40 heterosexual men who were currently involved in a dating relationship that had been ongoing for at least 1 month (M = 13.8 months, SD = 16.0). Participants reported a mean age of 19.38 (SD = 1.61), most were first year undergraduates (62.5%), and most (75.0%) identified as Caucasian (10.0% identified as African American, 12.5% identified as Asian American, and 2.5% identified as Hispanic or Latino). All participants received partial fulfillment of a course requirement in exchange for their participation.

Procedure and measures

After signing up for the study through the University’s online research system, participants read and signed a consent form approved by the local IRB. Then, paralleling the methods of Study 1, all participants completed a measure of (a) the extent to which they perceived that their female relationship partner valued them for their body and their non-physical qualities, (b) the extent to which they perceived that their partner was committed to a long-term relationship with them, and (c) relationship satisfaction.

Body valuation

To assess the extent to which participants perceived that their partners valued them for their body, like in Study 1, participants answered the following question: “How much do you think your relationship partner values you for your body?,” where 0 = not at all and 100 = completely. To determine how men interpreted this item, we also asked them the same four questions we asked women in the pilot study described in Study 1. Whereas the pilot study described in Study 1 demonstrated that women interpreted the body valuation item as asking the extent to which their partner believes their body is attractive to look at and available for sex, men in this study appeared to interpret the body valuation item as asking the extent to which their partner values their body because it is attractive to look at.

Non-physical valuation

To assess the extent to which participants perceived that their partners valued them for their non-physical qualities, participants completed the 13-item measure used in Study 1. Internal consistency was high (Chronbach’s α = .91).

Commitment to a long-term relationship

To assess the extent to which participants perceived that their partners were committed, participants answered the following question used in Study 1: “What kind of relationship do you think this is for your partner?” where 0 = completely short-term relationship and 100 = completely long-term relationship.

Relationship satisfaction

As in Study 1, we assessed global relationship satisfaction using SMD. Internal consistency was high (Chronbach’s α = .91).

Covariates

We collected information on height and weight after participants had completed the study. We were only able to reach 27 participants who reported their height and weight. Thus, results controlling BMI are restricted to this subsample. As in Study 1, we also controlled for participants’ age and relationship length, after it had been log transformed.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 5. A few of these are worth highlighting. First, like in Studies 1 and 2, participants reported relatively high levels of relationship satisfaction and high confidence that their partners were committed to a long-term relationship, on average. Nevertheless, there was substantial variability in both reports. Second, participants’ mean BMI was in the normal weight range (see CDC; 2009). Third, men perceived that their partners valued them for their bodies and their non-physical attributes, on average. Nevertheless, there was substantial variability in those reports as well. Notably, consistent with what was found in Study 1, men perceived less body valuation than non-physical valuation from their partners (t(39) = −4.33, p < .001, Cohen’s d =1.39). Fourth, not surprisingly and consistent with what was found in Studies 1 and 2, perceived partner commitment was positively associated with relationship satisfaction and perceived body valuation was significantly positively associated with perceived non-physical valuation. Finally, also consistent with what was found in Study 1, whereas perceived non-physical valuation was positively associated with perceived relationship commitment and relationship satisfaction, perceived body valuation was not associated with either variable, on average.

Table 5. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study 3.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Body Valuation | -- | ||||

| (2) Non-Physical Valuation | .64*** | -- | |||

| (3) Commitment | .20 | .34* | -- | ||

| (4) Relationship Satisfaction | .13 | .51** | .46** | -- | |

| (5) BMI | −.12 | .10 | −.34† | −.13 | -- |

|

| |||||

| M | 68.40 | 81.30 | 78.68 | 86.51 | 23.88 |

| SD | 24.39 | 15.40 | 24.28 | 12.13 | 5.18 |

Note. N = 40 for all variables except BMI; N = 27 for BMI variable.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

To examine the interactive effects of (a) perceived body valuation, (b) non-physical valuation, and (c) partner commitment on men’s relationship satisfaction, we regressed men’s relationship satisfaction onto the standardized score of perceived body valuation, the standardized score of perceived non-physical valuation, the standardized score of perceived partner commitment, and all possible interactions. Results are reported in Table 6. As can be seen there, consistent with what was found in Study 1, perceived partner commitment and perceived non-physical valuation were positively associated with relationship satisfaction. Additionally, the Body Valuation × Partner Commitment interaction was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction and the Non-Physical Valuation × Partner Commitment interaction was positively associated with relationship satisfaction. Nevertheless, those main effects and 2-way interactions were qualified by a significant positive Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation × Partner Commitment interaction. Notably, this effect remained significant controlling participants’ BMI, age, and the log of relationship length in the smaller sample of 27 men (B = 19.43, SE = 6.88, t(16) = 2.83, p = .012).

Table 6. Study 3—Associations between Men’s Perceived Partner Body Valuation, Perceived Non-Physical Valuation, Perceived Commitment, Their Interactions, and Men’s Relationship Satisfaction.

| Relationship Satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE |

Effect Size

r |

|

| Intercept | 84.54 | 1.47 | -- |

| Body Valuation (B) | −2.82 | 1.74 | .28 |

| Non-Physical Valuation (NP) | 7.33 | 2.80 | .42* |

| Partner Commitment (C) | 3.89 | 1.52 | .41* |

| B × NP | 3.46 | 2.23 | .26 |

| B × C | −5.47 | 2.27 | .39* |

| NP × C | 8.99 | 3.45 | .42* |

| B × NP × C | 3.27 | 1.37 | .39* |

Note. dfs = 32. Effect size .

p < .05.

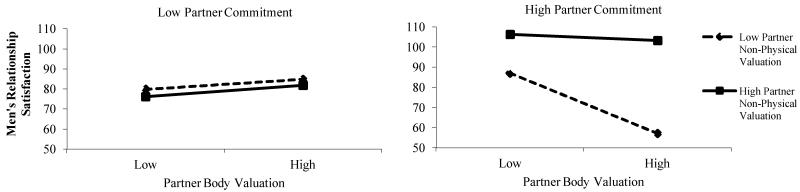

To view the nature of that 3-way interaction, we decomposed it by plotting the predicted means for individuals 1 SD above and below the mean on each variable involved in the interaction. That plot is depicted in Figure 3. As can be seen there, the direction in which perceived body valuation was associated with relationship satisfaction depended on whether or not men also perceived that their partner (a) valued them for their non-physical qualities and (b) was committed to a long-term relationship.

Figure 3.

Study 3—Interactive Effects of Perceived Partner Valuation for Body, Perceived Partner Valuation for Non-Physical Qualities, and Perceived Partner Commitment on Men’s Relationship Satisfaction

To determine the simple effects of body valuation, we first tested the statistical significance of each simple Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation interaction. Similar to what was found among women in Study 1, among men who perceived that their partner was 1 SD less committed than the mean, the Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation interaction was not significant (B = 0.19, SE = 2.21, t(32) = 0.09, ns). However, unlike the finding of Studies 1 and 2 that women were less satisfied to the extent that less committed men valued them for their body, neither body valuation nor non-physical valuation by a partner was associated with relationship satisfaction among men who perceived their partner was relatively less committed (B = 2.65, SE = 3.11, t(32) = 0.85, ns and B = −1.67, SE = 5.29, t(32) = −0.32, ns, respectively). Consistent with what was found in Study 1, however, among men who perceived that their partners were 1 SD more committed than the mean, the Body Valuation × Non-Physical Valuation interaction was significant (B = 6.73, SE = 2.97, t(32) = 2.27, p = .030). Nevertheless, the pattern of that interaction was different than the pattern that emerged in Studies 1 and 2.Whereas body valuation by a committed partner was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction among men who perceived their partner valued them for their non-physical qualities 1 SD less than the mean (B = −15.02, SE = 4.22, t(32) = −3.56, p = .001), body valuation by a committed partner was not associated with relationship satisfaction among men who perceived their partner valued them for their non-physical qualities 1 SD more than the mean (B = −1.55, SE = 3.63, t(32) = −0.43, ns).

General Discussion

Women are frequently valued for their bodies by their intimate partners (Chen & Brown, 2005; Fletcher et al., 1999; Kurzban & Weeden, 2005; Legenbauer et al., 2009). Nevertheless, although a robust literature has examined the implications of body valuation by strangers, we are aware of only one study that has examined the effects of body valuation by an intimate partner. Specifically, Zurbriggen and colleagues (2011) demonstrated that increased perceived partner objectification by a male partner was negatively associated with women’s relationship satisfaction. However, non-physical valuation and commitment were not assessed in that study. Because women who are valued for their bodies by an intimate partner who is committed and values them for their non-physical qualities may feel that they are meeting all their partner’s standards, we predicted that body valuation by such a partner would be positively associated with women’s relationship satisfaction.

Two independent studies supported this prediction by revealing a three-way interaction between body valuation, non-physical valuation, and perceived partner commitment on women’s relationship satisfaction. Specifically, whereas the extent to which a committed intimate partner valued a woman for her body was positively associated with that woman’s relationship satisfaction when that partner also valued her for her non-physical qualities, body valuation was (a) unrelated to satisfaction when the partner was committed but demonstrated relatively low levels of non-physical valuation and (b) negatively associated with satisfaction when the partner was relatively uncommitted, regardless of how much he also valued the woman for her non-physical qualities. Notably, this pattern appears to be quite robust, as it emerged (a) across two independent studies, (b) in a sample of dating participants and a sample of married couples, (c) using women’s perceptions of partner valuation and self-reported partner valuation, (d) using two different measures of satisfaction and two different measures of perceived commitment, and (e) held controlling for women’s actual body size, age, and relationship length.

Given the significant results that emerged among women, and given that men are also valued for their appearance by female partners (Baucom et al., 1996; Eastwick & Finkel, 2008; Fletcher & Simpson, 2000; Fletcher et al., 1999; Hassebrauck, 1997), we also examined the implications of body valuation for men’s relationship satisfaction. Although men’s perceptions of body valuation by a female partner also interacted with their perceptions of non-physical valuation and commitment, the pattern was somewhat different. Specifically, whereas perceived body valuation by a committed partner was not associated with relationship satisfaction among men who were also valued for their non-physical qualities, perceived body valuation by a committed partner was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction among men who were less valued for their non-physical qualities. Moreover, men appeared to perceive body valuation as the extent to which their partners value their body for how attractive it is to look at, rather than how useful their body is specifically for sex or its non-sexual functions.

Theoretical Implications

These three studies have several important theoretical implications. First, these findings join others demonstrating the important role of the interpersonal context in determining the implications of interpersonal processes for well-being (e.g. McNulty & Fincham, 2012; Reis, 2008; Reis, Collins, & Berscheid, 2000). In contrast to the robust literature on objectification that indicates women experience undesirable outcomes when they are valued for their bodies in the context of society and by strangers (Calogero, 2004; Fairchild & Rudman, 2008; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997, Szymanski & Henning, 2007), these findings indicate that qualities of the interpersonal context determines whether women are harmed or actually benefit from being valued for their bodies. Indeed, whereas research on objectification tends to examine the implications of body valuation by strangers and thus confounds valuing people for their bodies with valuing people only for their bodies, the current research demonstrates that considering the extent to which body valuation is accompanied by non-physical valuation and occurs in the context of committed, intimate relationships is important; whereas women who were valued for their bodies by uncommitted partners were less satisfied with their relationships regardless of whether those partners valued them for their non-physical qualities, women who were valued for their bodies by a committed partner were more satisfied with their relationships as long as that partner also valued them for their non-physical qualities.

Likewise, although prior work demonstrates that men are unaffected by body valuation (Lindberg, Hyde, & McKinley, 2006), such null effects also appear to depend on the interpersonal context. Whereas men who were valued for their bodies by uncommitted partners or by committed partners who also valued them for their non-physical qualities were no more or less satisfied when their partner valued them for their body, men who were valued by committed partners who did not value them for their non-physical qualities were less satisfied when their partner valued them for their body. Of course, this negative effect was not predicted and thus any explanation of it is post-hoc. However, it may be that men who are being valued for their bodies in a commitment relationship but not for their other, non-physical qualities are particularly vulnerable to feeling like sexual objects because men are expected to be more agentic than are women (Bem, 1974). Future research may benefit from addressing the mechanism of any differences in the implications of body valuation for men and women.

Second, the current findings also add to a growing body of research suggesting that women’s body size, body-related thoughts, attractiveness, and sexuality have important implications for women’s relationship outcomes (Fisher & McNulty, 2008; Little, McNulty, & Russell, 2010; McNulty, Neff, & Karney, 2008; Meltzer & McNulty, 2010; Meltzer et al., 2011; Russell & McNulty, 2011). For example, women’s body size, relative to their spouses’, has implications for both spouses’ relationship satisfaction; husbands are more satisfied at the time of marriage and remained more satisfied over time to the extent that their wives have lower BMIs than their own, and wives demonstrate less decline in satisfaction over time to the extent that they have lower BMIs than their husbands (Meltzer et al., 2011). Likewise, controlling for the actual size of women’s bodies, women’s attitudes regarding their bodies positively predicts their levels of intimacy and both spouses’ relationship satisfaction (Meltzer & McNulty, 2010).

Strengths and Limitations

Several strengths of the current research enhance our confidence in the results reported here. First, although a single-item measure was used to assess body valuation, we pilot tested this item to clarify which aspects of body valuation were responsible for the effects that emerged. Second, helping to ensure that the results reported here were not idiosyncratic to different measurement techniques or samples, the effects for women’s satisfaction replicated across two independent studies using samples of two different populations (dating versus married couples), using both men’s and women’s reports of the extent to which men value women for their body, and using two different measures of relationship satisfaction and perceived commitment. Third, the effects held controlling for participants’ BMI, thus decreasing the likelihood that the results were spurious because of associations with body size. Finally, all studies used participants who responded based on their actual intimate relationships, rather than hypothetical, laboratory-based, or prior relationships. Thus, the outcome measure, relationship satisfaction, was both real and consequential.

Nevertheless, several factors limit interpretations of the current findings until they can be replicated and extended. First, the current studies utilized cross-sectional, correlational data making it difficult to draw causal conclusions. For example, rather than the key interaction causing satisfaction, because of processes of sentiment override (Weiss, 1980), satisfaction may have caused the key interaction—i.e., more satisfied people may see their partners as more committed and more likely to value them for their bodies and non-physical qualities. Future research may benefit by examining the interpersonal effects of body and non-physical valuation using either longitudinal or experimental data. Second, although the one-item commitment measures used here were high in face validity, and although Studies 1 and 2 demonstrated the same effect using different one-item commitment measures, the single-item measures of commitment leave it unclear what aspects of commitment were responsible for the effects that emerged. For example, partners can be committed to their relationships because of dedication to the relationship or the inability to leave it (e.g., Stanley & Markman, 1992). It is unclear whether perceptions of both types of commitment would similarly affect the targets of body valuation. Future research may benefit by addressing this issue. Third, although the current studies involved heterosexual women and men in dating relationships and relatively new marriages, generalizations to other populations should be made with caution. For example, it is unclear whether similar effects would occur among homosexual couples—it is possible that the effects reported in Studies 1 and 2 are driven not by the participant’s sex but by body valuation from a man. In other words, it is plausible that gay men may demonstrate a pattern of effects that is more consistent with those in Studies 1 and 2 than those in Study 3. Accordingly, future research may benefit from addressing the effects of partner body valuation in other populations of couples. Fourth, both studies were comprised of mostly White women and men living in the United States. Thus, generalizations to other races and cultures should be made with caution. For example, because Black women face different body-related standards in their romantic relationships (Harris, Walters, & Waschull, 1991), the effects of body valuation on Black women’s relationship satisfaction may differ from those reported here. Future research may benefit by addressing these issues in more diverse samples of participants. Fifth, there may be other moderators of these effects not examined in the current studies. For example, because it would have been evolutionarily adaptive for women to select partners who (a) valued them for their bodies, (b) valued them for their non-physical qualities, and (c) were committed to a long-term relationship, it may be that the key effect demonstrated in Studies 1 and 2 are particularly strong among highly fertile women. Future research may benefit by addressing this and other potential moderators of the effect reported here. Finally, although we referenced work on objectification theory, these studies did not examine the implications of true objectification. Objectification involves reducing an individual to their body and body parts (Bartky, 1990; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Our research examined the implications of body valuation by an intimate partner. Although there may be similarities between the two constructs, there are important differences. Most notably, men who valued women for their bodies were not necessarily reducing women to their bodies and body parts. Indeed, even the men in Study 2 who reported low levels of non-physical valuation relative to the sample nevertheless still valued those women for such qualities. In sum, true objectification may be particularly unlikely in committed relationships. Nevertheless, if and when it does occur, the implications may be universally negative. Future research may benefit by assessing and examining the implications of any objectification that occurs in intimate relationships.

Acknowledgments

Preparation for this article was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Development Grant RHD058314A.

Footnotes

The equivalent measure of husbands’ reports of commitment did not interact with body and non-physical valuation (B = −0.43, SE = 0.74, t(62) = −0.57, ns). However, this non-significant interaction makes sense given that wives’ perceptions of commitment did not reflect husbands’ commitment (the correlation between husbands and wives’ commitment was r = .09, ns).

Contributor Information

Andrea L. Meltzer, Department of Psychology, Southern Methodist University

James K. McNulty, Department of Psychology, Florida State University

References

- Amodio DM, Showers CJ. ‘Similarity breeds liking’ revisited: The moderating role of commitment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:817–836. [Google Scholar]

- Aubrey JS. Effects of sexually objectifying media on self-objectification and body surveillance in undergraduates: Results of a 2-year panel study. Journal of Communication. 2006;56:366–386. [Google Scholar]

- Baker L, McNulty JK. Shyness and marriage: Does shyness shape even established relationships? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:665–676. doi: 10.1177/0146167210367489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L, McNulty JK. Self-compassion and relationship maintenance: The moderating roles of conscientiousness and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:853–873. doi: 10.1037/a0021884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LR, McNulty JK, Overall NC, Lambert NM, Fincham FD. How do relationship maintenance behaviors affect individual well-being? A contextual perspective. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2013;4:282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Bartky SL. Femininity and domination: Studies in the phenomenology of oppression. New York: Routledge: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Epstein N, Rankin LA, Burnett CK. Assessing relationship standards: The Inventory of Specific Relationship Standards. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:72–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman R, DeLucia J. Accuracy of self-reported weight: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy. 1992;23:637–655. [Google Scholar]

- Boyes AD, Latner JD. Weight stigma in existing romantic relationships. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2009;35:282–293. doi: 10.1080/00926230902851280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM, Schmitt DP. Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review. 1993;100:204–232. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calogero RM. A test of objectification theory: The effect of the male gaze on appearance concerns in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Simpson JA, Kashy DA, Fletcher GJO. Ideal standards, the self, and flexibility of ideals in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention About BMI for Adults. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Chen EY, Brown M. Obesity stigma in sexual relationships. Obesity Research. 2005;13:1393–1397. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:591–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Trost MR. Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. 4th edition Vol. 2. McGraw-Hill; Boston: 1998. pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano DL, Thompson JK. Body image and body shape ideals in magazines: Exposure, awareness, and internalization. Sex Roles. 1997;37:701–721. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwick PW, Finkel EJ. Sex differences in mate preferences revisited: Do people know what they initially desire in a romantic partner? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:245–264. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild K, Rudman LA. Everyday stranger harassment and women’s objectification. Social Justice Research. 2008;21:338–357. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher TD, McNulty JK. Neuroticism and marital satisfaction: The mediating role played by the sexual relationship. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:112–122. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA. Ideal standards in close relationships: Their structure and functions. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9:102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA, Thomas G, Giles L. Ideals in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:72–89. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Roberts T–A. Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21:173–206. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Roberts T–A, Noll SM, Quinn DM, Twenge JM. That swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:269–284. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye NE, McNulty JK, Karney BR. How do constraints on leaving a marriage affect behavior within the marriage? Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:153–161. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais SJ, Vescio TK, Allen J. When are people interchangeable sexual objects? The effect of gender and body type on sexual fungibility. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MB, Harris RJ, Bochner S. Fat, four eyed, and female: Stereotypes of obesity, glasses, and gender. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1982;12:503–516. [Google Scholar]

- Harris MB, Walters LC, Waschull S. Gender and ethnic differences in obesity-related behaviors and attitudes in a college sample. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1991;22:1545–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Hassebrauck M. Cognitions of relationship quality: A prototype analysis of their structure and consequences. Personal Relationships. 1997;4:163–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kozee HB, Tylka TL, Augustus-Horvath CL, Denchik A. Development and psychometric evaluation of the interpersonal sexual objectification scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:176–189. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzban R, Weeden J. Do advertised preferences predict the behavior of speed daters? Personal Relationships. 2005;14:623–632. [Google Scholar]

- Langis J, Sabourin S, Lussier Y, Mathieu M. Masculinity, femininity, and marital satisfaction: An examination of theoretical models. Journal of Personality. 1994;62:393–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legenbauer T, Vocks S, Schäfer C, Schütt-Strömel S, Hiller W, Wagner C, Vögele C. Preference for attractiveness and thinness in a partner: Influence of internalization of the thin ideal and shape/weight dissatisfaction in heterosexual women, heterosexual men, lesbians, and gay men. Body Image. 2009;6:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JM. Reaction to opinion deviance in small groups. In: Paulus P, editor. Psychology of Group Influence. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1980. pp. 375–427. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg SM, Hyde JS, McKinley NM. A measure of objectified body consciousness for preadolescent and adolescent youth. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2006;30:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Liss M, Erchull MJ, Ramsey LR. Empowering or oppressing? Development and exploration of the Enjoyment of Sexualization Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37:55–68. doi: 10.1177/0146167210386119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little KC, McNulty JK, Russell VM. Sex buffers intimates against the negative implications of attachment insecurity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:484–498. doi: 10.1177/0146167209352494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. Forgiveness increases the likelihood of subsequent partner transgressions in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:787–790. doi: 10.1037/a0021678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Fincham FD. Beyond positive psychology? Toward a contextual view of psychological processes and well-being. American Psychologist. 2012;67:101–110. doi: 10.1037/a0024572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Neff LA, Karney BR. Beyond initial attraction: Physical attractiveness in newlywed marriages. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:135–143. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Russell VM. When “negative” behaviors are positive: A contextual analysis of the long-term effects of problem-solving behaviors on changes in relationship satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:587–604. doi: 10.1037/a0017479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer AL, McNulty JK. Body image and marital satisfaction: Evidence for the mediating role of sexual frequency and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:156–164. doi: 10.1037/a0019063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer AL, McNulty JK, Novak SA, Butler EA, Karney BR. Marriages are more satisfying when wives are thinner than their husbands. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2011;2:416–424. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SL, Maner JK. Evolution and relationship maintenance: Fertility cues lead committed men to devalue relationship alternatives. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46:1081–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin DW. The self-fulfilling nature of positive illusions in romantic relationships: Love is not blind, but prescient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:1155–1180. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood CE, Suci GJ, Tannenbaum PH. The measurement of meaning. University of Illinois Press; Urbana, IL: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen WC, Miller LC, Putcha-Bhagavatula AD, Yang Y. Evolved sex differences in the number of partners desired? The long and the short of it. Psychological Science. 2002;13:157–161. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn BA. Sexual harassment and masculinity: The power and meaning of “girl watching”. Gender and Society. 2002;16:386–402. [Google Scholar]

- Regan PC, Levin L, Sprecher S, Christopher FS, Cate R. Partner preferences: What characteristics do men and women desire in their short-term sexual and long-term romantic partners? Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 2000;12:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT. Reinvigorating the concept of situation in social psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2008;12:311–329. doi: 10.1177/1088868308321721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Collins WA, Berscheid E. The relationship context of human behavior and development. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:844–872. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Kumashiro M, Kubacka KE, Finkel EJ. “The part of me that you bring out:” Ideal similarity and the Michaelangelo phenomenon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:61–82. doi: 10.1037/a0014016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell VM, McNulty JK. Frequent sex protects intimates from the negative implications of their neuroticism. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2011;2:220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Sheets V, Ajmere K. Are romantic partners a source of college students’ weight concern? Eating Behaviors. 2005;6:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1992;54:595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Swim JK, Hyers LL, Cohen LL, Ferguson MJ. Everyday sexism: Evidence for its incidence, nature, and psychological impact from three daily diary studies. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Henning SL. The role of self-objectification in women’s depression: A test of objectification theory. Sex Roles. 2007;56:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill R, Gangestad SW. The evolutionary biology of human female sexuality. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M. Person × situation interactions in body dissatisfaction. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;29:65–70. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200101)29:1<65::aid-eat10>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovée MJ, Maisey DS, Emery JL, Cornelissen PL. Visual cues to female physical attractiveness. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 1999;266:211–218. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RL. Strategic behavioral marital therapy: Toward a model for assessment and intervention. In: Vincent JP, editor. Advances in family intervention, assessment, and theory. Vol. I. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1980. pp. 229–271. [Google Scholar]

- Zurbriggen EL, Ramsey LR, Jaworski BK. Self- and partner-objectification in romantic relationships: Associations with media consumption and relationship satisfaction. Sex Roles. 2011;64:449–462. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-9933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]