Abstract

Sex hormones strongly influence body fat distribution and adipocyte differentiation. Estrogens and testosterone differentially affect adipocyte physiology, but the importance of estrogens in the development of metabolic diseases during menopause is disputed. Estrogens and estrogen receptors regulate various aspects of glucose and lipid metabolism. Disturbances of this metabolic signal lead to the development of metabolic syndrome and a higher cardiovascular risk in women. The absence of estrogens is a clue factor in the onset of cardiovascular disease during the menopausal period, which is characterized by lipid profile variations and predominant abdominal fat accumulation. However, influence of the absence of these hormones and its relationship to higher obesity in women during menopause are not clear. This systematic review discusses of the role of estrogens and estrogen receptors in adipocyte differentiation, and its control by the central nervous systemn and the possible role of estrogen-like compounds and endocrine disruptors chemicals are discussed. Finally, the interaction between the decrease in estrogen secretion and the prevalence of obesity in menopausal women is examined. We will consider if the absence of estrogens have a significant effect of obesity in menopausal women.

1. Introduction

Obesity and obesity-related disorders such as diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM type 2), cardiovascular disease, and hypertension are worldwide epidemics with a greater percentage of increase in developing countries [1–3]. Many genetic and epigenetic factors determine the pathophysiology of body fat accumulation [4, 5]. The majority of these factors can be classified into different categories [6–9] such as (1) factors responsible for the hormonal regulation of appetite and satiety; (2) factors that regulate body glucose levels [10–12]; (3) regulators of basal metabolic rate [13, 14]; (4) factors that control the quantity, disposition, and distribution of fat cells [15, 16]; (5) modulators for the differentiation of progenitor cells [17, 18]; and (6) those factors that determine adipocyte cell lineage [19, 20]. Adipocytes may also regulate the production of cytokines that control the satiety and hunger centers in the central nervous system and modulate energy expenditure in other tissues [21–23].

The increases in overweight and obesity in menopausal women are important public health concerns [24, 25]. The prevalence of obesity, which is closely associated with cardiovascular risk, increases significantly in American women after they reach age 40; the prevalence reaches 65% between 40 and 59 years and 73.8% in women over age 60 [26]. Unfortunately, there are a limited number of drugs for treatment of obesity, because the majority of new products have been recalled due to side effects [27–29].

The reasons for increasing obesity in menopausal women are not clear. Some researcher arguments that the absence of estrogens may be an important obesity-triggering factor [30]. Estrogens deficiency enhances metabolic dysfunction predisposing to DM type 2, the metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases [31, 32]. As a result of increases of life expectancy in developed countries, many women will spend the second half of their lives in a state of estrogen deficiency. Thus, the contribution of estrogen deficiency in the pathobiology of multiple chronic diseases in women is emerging as a conceivable therapeutic challenge of the 21st century. However, environmental epigenetic factors may also contribute to obesity and a cultural bias that also hinders women's efforts to combat obesity [33, 34]. Perhaps it is a combination of the aforementioned factors, but the triggers for obesity require further investigation. To address this growing problem, improved understanding of how estrogens contribute to energy balance, lipid, and glucose homeostasis promises to open a novel therapeutic applications for an increasing large segment of the female population. The potential therapeutic relevance of estrogen physiology, estrogen receptors, and the estrogen pathway will be discussed in this manuscript.

2. Methods

The study design was a review of existing published original papers and reviews. We conducted this review of SSBs and health outcomes in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Statement (PRISMA) [35]. PubMed publications until Nov 30, 2013, were taken into account.

3. Estrogens and Estrogen Receptors in Fat Metabolism

The hormones help integrate metabolic interaction among major organs that are essential for metabolically intensive activities like reproduction and metabolic function. Sex steroids are required to regulate adipocyte metabolism and also influence the sex-specific remodeling of particular adipose depots [36, 37]. In humans, the factors that control fat distribution are partially determined by sex hormones concentrations [38]. Men, on average, have less total body fat but more central/intra-abdominal adipose tissue, whereas women tend to have more total fat that favors gluteal/femoral and subcutaneous depots [39]. Weight and fat abdominal distribution differ among women of reproductive age and menopausal women [40, 41]. The decrease in estrogen levels in menopausal women is associated with the loss of subcutaneous fat and an increase in abdominal fat [42]. The importance of estrogens in subcutaneous fat accumulation is evident; in fact estrogen hormonal therapy in men also increases the amount of subcutaneous fat [43, 44].

In humans, 17-β-estradiol (E2) is the most potent estrogen followed by estrone (E1) and estriol (E3) [45]. The expression of genes that encode the enzymes in estrogen synthetic pathway such as aromatase and reductive 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (17β-HSD) is critical for E2 formation [46]. Protein products of several genes with overlapping functions may confer reductive 17β-HSD activities in peripheral tissues [47].

Estrogens function is mediated by nuclear receptors that are transcription factors that belong to the superfamily of nuclear receptors. Two types of estrogen receptors (ERs) have been identified, the alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ) receptors [48, 49]. The classical genomic action mechanism of ER action typically occurs within hours, leading to activation or repression of target genes. In this classical signaling pathway, ligand activated ER dissociates from its chaperone heat-shock protein and binds as a dimer directly to an estrogen response element (ERE) in the promoter of target genes [50–52], although it was considered that the action of E2 was subject to an action in gene expression regulation. Recently, there is increasing evidence of nonnuclear cytosolic or plasma membrane-associate receptors that mediate nongenomic and rapid effects of several steroid hormones [53–55]. In this manner, the traditional estrogen nuclear receptors have been found to function outside of the nucleus to direct nongenomic effects [56].

Several mechanisms of membrane-signaling activation can explain rapid responses to E2. These rapid actions include activation of kinase, phosphatase, and phospholipase that can mediate calcium-dependent signaling and can mediate downstream nongenomic physiological responses, such as effects on cell cycle, cell survival, and energy metabolism [57, 58].

Human subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues express both ERα and ERβ [59, 60], whereas only ERα mRNA has been identified in Brown adipose tissue [61, 62]. ERα plays a major role in the activity of adipocytes and sexual dimorphism of fat distribution. Female and male mice that lack ERα have central obesity, have severe insulin resistance, and are diabetic [63–65]. Although not all studies are in agreement, polymorphism of ERα in humans have been associated with risk factors for cardiovascular diseases [66].

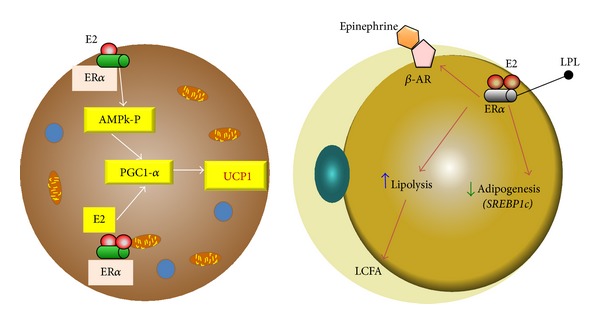

Lipolysis in humans is controlled primarily by the action of β-adrenergic receptors (lipolytic) and α2A-adrenergic receptors (antilipolytic) [67]. Estrogen seems to promote and maintain the typical female type of fat distribution that is characterized by accumulation of adipose tissue, especially in the subcutaneous fat depot, with only modest accumulation of intra-abdominal adipose tissue [68]. Estradiol directly increases the number of antilipolytic α2A-adrenergic receptors in subcutaneous adipocytes [69]. Visceral adipocytes exhibit a high α2A/β ratio, and these cells are stimulated by epinephrine; in contrast, no effect of estrogen on α2A-adrenergic receptor mRNA expression was observed in adipocytes from the intra-abdominal fat depot [70]. However, it is important to highlight that the effects of estrogens differs on the route of administration and the lipolytic influence of estrogens on fat accumulation affects specific regions of the body [71–73]. E2 may also increase beta adrenoreceptor expression through ERα [74]. These results provide a mechanism insight for the effect of E2 on the maintenance of fat distribution with an increased use of lipids as energy source, which partially promotes fat reduction in abdominal fat. This effect occurs via the facilitation of fat oxidation in the muscle by the inhibition of lipogenesis in the liver and muscle through the regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and an increase in LPL expression [75–77]. E2 also increases muscle oxidative capacity by means of the regulation of acyl-CoA oxidase and uncoupling proteins (UCP2-UCP3), which enhances fatty acid uptake without lipid accumulation [78, 79]. Therefore, E2 improves fat oxidation through the phosphorylation of AMP-kinase (AMPK) in muscle and myotubes in culture [80, 81] and malonyl-CoA inactivation by increasing the affinity of carnitine palmitoyltransferase [82] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Estrogen in the fat cell. (a) In brown adipocyte cell the ER alpha receptor can increase the expression of UCP1 by increasing PGC1alpha coactivator through AMPk and by a direct effect on the receptor coactivator. (b) In white adipocyte ER alpha receptor activation by estrogen reduces lipoprotein lipase and increases beta-adrenergic receptor activity. UCP1: uncoupling protein 1; PGC1alpha: peroxisome proliferative activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha; ER: estrogen receptor; AMPk: AMP-activated protein kinase. LPL: lipoprotein lipase; β-AR: adrenergic receptor beta.

4. Estrogens Control of Central Nucleus of Appetite and Satiety

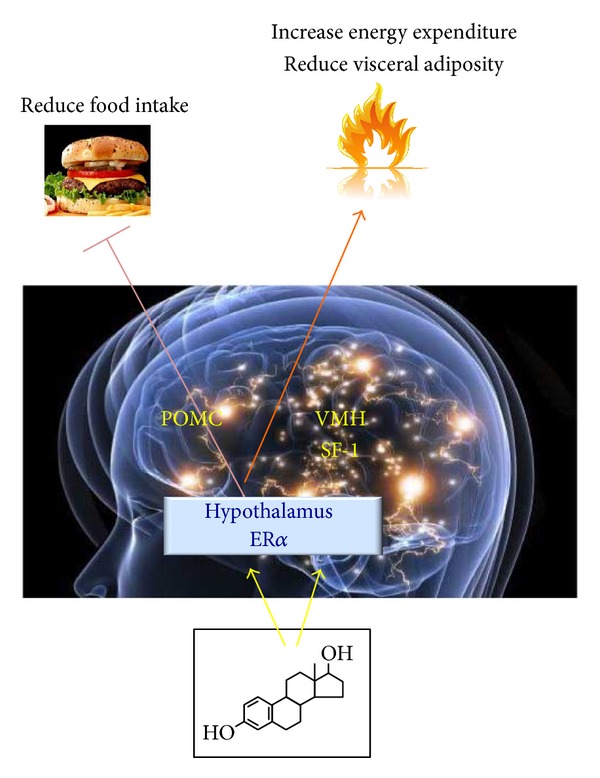

The hypothalamus is an important center in the brain for the coordination of food consumption, body weight homeostasis, and energy expenditure [83–85]. Some areas of the hypothalamus, including the ventromedial (VMN), arcuate (ARC), and paraventricular (PVN) nuclei, regulate physiological events that control weight [86]. The process by which estrogens regulate the activity of the hypothalamic nuclei is complex [87, 88]. Estrogens directly and indirectly modulate the activity of molecules involved in orexigenic action, which induces an increase in food intake [89, 90]. However, estrogen receptors regulate the neuronal activity of energy homeostasis and reproductive behaviors in a different mode. While ERα is abundantly expressed in the rodent brain in VMN and ARC, PVN, and the medial preoptic area, ERβ is found in the same hypothalamic nuclei, but ERβ expression is significantly lower relative to ERα [88, 91]. POMC neurons within the ARC modulate food intake, energy expenditure, and reproduction. ARC POMC ERα mRNA levels fluctuate over the course of the estrous cycle, with the most dramatic increase on the day of proestrus, when E2 concentration is highest [92]. Estrogens directly act on POMC neurons and regulate their cellular activity. Recent findings provide additional support for the importance of ERα POMC neurons and the suppression of food intake. Indeed, deletion of ER in POMC neurons in mice leads to hyperphagia without directly influencing energy expenditure or adipose tissue distribution [88]. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) is a potent orexigenic that increases food intake during fasting conditions and following food consumption by acting primarily on the ARC and PVN in the hypothalamus [93]. NPY exhibits decrease orexigenic activity after exposure to estrogens. This inhibitory action is due to the estrogen modulation of NPY mRNA expression and receptor activity [93, 94]. Ghrelin peptide is produced by parietal cells in the stomach, and it regulates feeding behaviors by sensing carbohydrate and lipid levels via stimulation of the growth hormone receptor. Ghrelin production is not limited to the stomach; different parts of the brain and some areas of the hypothalamus, such as the ARC and PVN nuclei, also produce ghrelin. Ghrelin antagonizes leptin action through the activation of hypothalamic neuropeptide Y/Y1 receptor pathway, augmented NPY gene expression, and increases food intake [95–97]. Estrogen hormone replacement therapy induces a decrease or no change in ghrelin activity [98]. Melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) promotes food consumption by acting directly on the lateral nucleus of the hypothalamus. Nerves that stimulate the MCH activity arise from the ARC nucleus and contain POMC, NPY, and Agouti-related protein (AgRP) [99–101]. The orexigenic effect of MCH is reduced in ovariectomized rats treated with estradiol [102, 103], which is likely a direct effect of the reduced affinity of the MCH receptor or the reduced expression of MCH mRNA [104, 105] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Estrogen hypothalamic control of obesity. ER alpha in the brain regulates body weight in both males and females ▸ ER alpha in female SF1 neurons regulates energy expenditure and fat distribution ▸ ER alpha in female POMC neurons regulates food intake. POMC: proopiomelanocortin; SF1: steroidogenic factor-1.

5. Estrogen and Energy Regulation

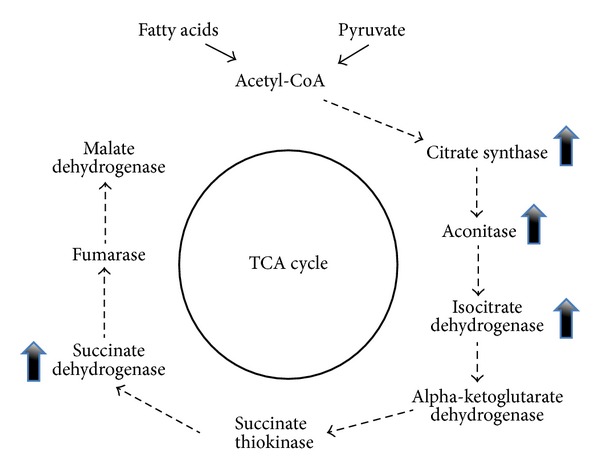

E2 administered to ovariectomized (OVX) mice fed with a high-fat diet preserved improve glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in WT but not in ERα −/− mice, suggesting that targeting of the ERα could represent a strategy to reduce the impact of high-fat diet induced in type 2 DM [106–108]. Insulin resistance is a central disorder in the pathogenesis of type 2 DM and also a feature observed in metabolic syndrome. Excess accumulation of adipose tissue in the central region of the body (intra-abdominal, “android,” or male-pattern obesity) correlates with increased risk of and mortality from metabolic disorders including type 2 DM [109]. As women enter menopause, there is a decline in circulating estrogen. This is accompanied by alterations in energy homeostasis that result in increases in intra-abdominal body fat. OVX rats, which are induced to exhibit obesity, regain normal weight after estrogen replacement [36, 110]. Although OVX induces a transient increase in food intake [111], hyperphagia does not fully account for changes in metabolism and development obesity after OVX [112]. Estrogens regulate glucose/energy metabolism via the direct and indirect control of the expression of enzymes that are involved in this process, such as hexokinase (HK), phosphoglucoisomerase (PGI), phosphofructokinase (PFK), aldolase (AD), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPD), phosphoglycerate kinase (PK) 6-phosphofructo 2-kinase, fructose 2,6-bisphosphatase, and glucose transporters Glut 3 and Glut 4 [79, 113–115]. Estrogens also increase the activity of several enzymes in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, including citrate synthase, mitochondrial aconitase 2, isocitrate dehydrogenase, and succinate dehydrogenase [82, 116, 117] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Estradiol availability affects the regulation of enzymes involved in tricarboxylic acid cycle activity. E2 enhances the glycolytic/pyruvate/acetyl-CoA pathway to generate electrons required for oxidative phosphorylation and ATP generation to sustain utilization of glucose as the primary fuel source.

Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) is a key-regulating enzyme for energy metabolism that breaks down plasma triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol. Estradiol modulates the activity of LPL wherein the promoter region contains estrogen response elements that interact with the estrogen receptor and inhibit mRNA expression in 3T3 cells and patients who are undergoing therapy with estradiol patches [118, 119]. The role of estrogens in mitochondria, which generate more than 90% of cellular ATP, must also be recognized. The mitochondria play an important role in the regulation of cell survival and apoptosis, and the respiratory chain is the primary structural and functional component that is influenced by estrogen activity [61]. The protective effect of estrogen on oxidative stress is mediated by translocation for specific enzymes from cytosol that prevent mitochondrial ADN of oxidative attack by free radicals [120].

Brown adipose (BAT) tissue is metabolically more active than white adipose tissue and its distribution changes with age. This adipose tissue is located in the neck, thorax, and major vessels in human neonates, but it is largely replaced by white adipose tissue in adults, which reaches the subcutaneous layers between muscles and the dermis, heart, kidney, and internal organs [17, 121, 122]. Brown adipose was considered absent in adult humans, but recently studies have shown that Brown adipose tissue may be stimulated in adults and might have a relevant role in the treatment of obesity [123]. Estrogens promote fat deposition after sexual maturation and alter the lipid profile. However, fat also increases in menopausal women, which suggests that estrogens play an important role in adipocyte differentiation. Experimental studies have shown that estrogens can intensify the thermogenic property of brown adipocytes, by an increase of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) mRNA expression [62, 124]. ERα is expressed in BAT tissue and mainly localized in mitochondria, which indicated that BAT mitochondria could be targeted by estrogens and pointed out the possible role of ERα in mitochondriogenesis [125]. Tissue estrogen sulfotransferase (EST) is a critical mediator of estrogen action. EST inhibits estrogen activity by conjugating a sulfonate group to estrogens, thereby preventing biding to estrogen receptors [126]. EST is expressed in adipose tissue and reduces adipocyte size, although an overexpression of EST in sc and visceral adipose tissue may induce insulin resistance. The role of EST in development of type 2 DM and metabolic syndrome is controversial [127, 128].

6. Estrogen and Adipokine Secretion

Estrogens may exert effects on several adipokines that are produced by adipocytes. Estrogen levels in premenopausal women are closely associated with leptin levels [129, 130]. Leptin may modulate energy balance in the hypothalamus by exerting an anorectic effect, and also it exhibits a lipolytic effect. Estrogen increases leptin sensitivity by controlling the expression of leptin-specific receptors [130–132].

Adiponectin is inversely associated with estrogen levels. This adipokine is involved in various inflammatory processes, endothelial function modulation, and protection against insulin resistance syndrome. Adiponectin plasma level is indirectly and negatively correlated with E2 plasma levels. Oophorectomy of adult mice increases adiponectin, which is reversed by E2 replacement [133–135].

Resistin is a hormone that is produced by adipocytes and contributes to obesity. The subcutaneous injection of estradiol benzoate reduces resistin levels in adipocytes [136].

Evidence from aromatase ArKo deficient models contributes to these observations. These mice develop a truncal obesity phenotype with increased gonadal and visceral adiposity and three times higher levels of circulating leptin without a marked increase in body weight [137]. Fat cell can produce proinflammatory adipocytokines that induce many of the complications of obesity like CD68, TNFα, or IL6. Administration of estrogens to ovariectomized female mice reduces significantly the mRNA of IL6, TNFα, and CD68. Furthermore, estrogen prevented female mice from developing liver steatosis and from becoming insulin resistant [72, 138].

7. Estrogen-Like Compounds and Endocrine Disruptors

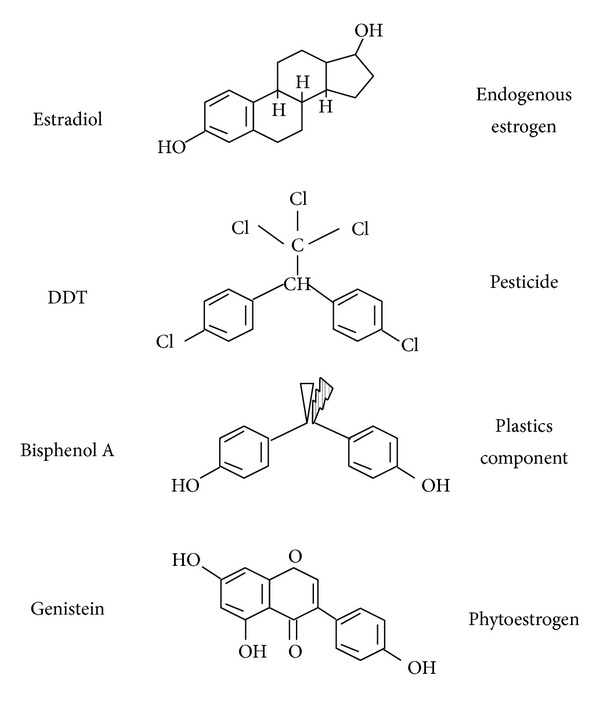

Some chemicals and plants derived compounds that may regulate the activity of estrogen receptors are potential obesogens [139]. The effect of tibolona, a synthetic substance with estrogenic activity, on body weight in postmenopausal women has been evaluated [140, 141]. One-year tibolona treatment decreases fat mass. However, tibolona combined with 17-β-estradiol and norethindrone acetate for 2 years does not significantly decrease fat mass [142]. The combination of hormone replacement therapy and tibolona in menopausal women increases body mass index (BMI), fat-free mass (FFM), free estrogen index (FEI), and free testosterone index (FTI), but the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) decreases after treatment with tibolona [142]. Genistein is phytoestrogen that has similarity in structure with the human female hormone 17-β-estradiol, which can bind to both alpha and beta estrogen receptors and mimic the action of estrogens on target organs. Genistein is present in soy, and it is popularly used in postmenopausal women. Genistein tends to induce obesity at low doses, but higher doses increase fatty acid oxidation and reduce fat accumulation in the liver [117, 143]. However, Genistein reverses the truncal fat accumulation in postmenopausal women and ovariectomized rodent models [144, 145].

Obesity is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors [146]. Some xenobiotics in the environment impair the normal control of various nuclear receptors or induce an adipogenic effect. The role of these endocrine disruptors in sexual behavior, menopause, and some gonadal diseases has been examined due to their modulation of estrogen receptor activity. Numerous chemicals and plants derived compounds, such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and heavy metals, exhibit estrogenic activity [147–150]. Many endocrine disruptors may affect the transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors by changing the action of competitively binding with ligand biding domain, which may modify coactivator activity and dissociate corepressors that reduce deacetylases action. Some endocrine disruptors may also modify DNA methylation in the regulatory region of specific genes. Furthermore, some of them may activate the phosphorylation of proteins [151, 152].

Endocrine disrupters may also be involved in different estrogenic intervention processes, such as the glycolytic pathway and during the regulation of glucose transporters with compounds like BPA, 4-nonylphenol (NP), 4-octylphenol (OP), and 4-propylphenol [116, 153, 154]. Endocrine disruption using these substances also interferes with tricarboxylic acid metabolism by decreasing key enzymes in mitochondrial activity, which could be partially related to obesity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Components with estrogens effects. Estrogen and some endocrine disruptors that have an estrogenic effect. DDT is a chemical fertilizer. Bisphenol A is an organic compound used to make polycarbonate polymers and epoxy resins; Genistein is an isoflavone found in a number of plants including soy. DDT: dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane.

In addition to these findings, many other estrogen-mediated pathways may be modulated by endocrine disruptors. Further studies are required to clarify the involvement of these chemicals.

8. Estrogen Therapy and Obesity

A growing body of evidence now demonstrates that estrogenic signaling can have an important role in obesity development in menopausal women. Menopausal women are three times more likely to develop obesity and metabolic syndrome abnormalities than premenopausal women [155]. Furthermore, estrogen/progestin based hormone replacement therapy in menopausal women has been shown to lower visceral adipose tissue, fasting serum glucose, and insulin levels [70, 156]. Estrogens also reduce the cardiovascular risk factors that increase during menopause. Therefore, estrogen therapy may exert a positive impact by reducing total cholesterol and relative LDL levels [157].

The estrogen type and route of administration appears to affect clinical outcomes. The changes in body fat distribution during menopause have led some researchers to suggest that hormone replacement therapy beneficially affects obesity in this group. To evaluate the metabolic effects of hormone replacement therapy using transdermal patches of 17-β-estradiol with medroxyprogesterone acetate in obese and nonobese menopausal women demonstrated greater fat loss [158]. Recent study participants in the most current WHI report were assigned to single estrogen therapy (0.625 mg/day conjugated equine estrogens) and combined estrogen/progestin therapy (0.625 mg conjugated equine estrogens plus 2.5 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate). An assessment of body composition using dual energy X-ray (DXA) absorptiometry at the six-year follow-up demonstrated a decrease in the loss of body fat mass with hormonal therapy in the first three years but not after six years [159–161]. However, the physiological form of estrogen is E2, and it is available in some oral preparations as well as all patches, creams, and gels for transdermal or percutaneous absorption. In contrast to orally administered HRT, transdermal delivery avoid first pass liver metabolism, thereby resulting in more stable serum levels without supraphysiological liver exposure [162].

A meta-analysis of over 100 randomized trials in menopausal women has analyzed the effect of HRT on components of metabolic syndrome. The authors conclude that, in women without diabetes, both oral and transdermal estrogen, with or without progestin, increase lean body mass, reduce abdominal fat, improve insulin resistance, decrease LDL/high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, and decrease blood pressure [163].

9. Conclusion

Hormone therapy during menopause will always be a mixed picture of benefits and risks. The data suggest that, for menopausal women of age 50 to 59 y or younger than age 60 y, the benefits of menopause hormone therapy outweigh the risks in many instances and particularly for relief of symptoms due to estrogen deficiency. Judgments about treatment require assessment of the needs in an individual patient and her potential for risk, such as breast cancer, coronary heart disease, fracture, stroke, obesity, and deep venous thrombosis. In order to reduce the obesity pandemic we consider that using menopause hormonal therapy with the lowest effective dose and for the shortest duration may be a possible coadjutant therapy. Future research should focus on identifying critical brain sites where ERs regulate body weight homeostasis and delineate the intracellular signal pathways that are required for the actions of estrogens. Moreover, understanding the genetics and epigenetics role of molecules that may play a role in estrogen activity in adipose tissue may reveal new pharmacological target for the beneficial action of estrogens. However, stringent studies in different locations around the world are essential to determine the real beneficial effect of estrogens for obesity treatment during menopause.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.van Hook J, Altman CE, Balistreri KS. Global patterns in overweight among children and mothers in less developed countries. Public Health Nutrition. 2013;16(4):573–581. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012001164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendez MA, Monteiro CA, Popkin BM. Overweight exceeds underweight among women in most developing countries. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;81(3):714–721. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.3.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olszowy KM, Dufour DL, Bender RL, Bekelman TA, Reina JC. Socioeconomic status, stature, and obesity in women: 20-year trends in urban Colombia. American Journal of Human Biology. 2012;24:602–610. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seki Y, Williams L, Vuguin PM, Charron MJ. Minireview: epigenetic programming of diabetes and obesity: animal models. Endocrinology. 2012;153(3):1031–1038. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heitmann BL, Westerterp KR, Loos RJ, et al. Obesity: lessons from evolution and the environment. Obesity Reviews. 2012;13:910–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagan S, Niswender KD. Neuroendocrine regulation of food intake. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2012;58(1):149–153. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myslobodsky M. Molecular network of obesity: what does it promise for pharmacotherapy? Obesity Reviews. 2008;9(3):236–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson KA, Martin NM, Bloom SR. Hypothalamic regulation of food intake and clinical therapeutic applications. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia e Metabologia. 2009;53(2):120–128. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302009000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Jaswal JS. Targeting intermediary metabolism in the hypothalamus as a mechanism to regulate appetite. Pharmacological Reviews. 2010;62(2):237–264. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musri MM, Parrizas M. Epigenetic regulation of adipogenesis. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 2012;15:342–349. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283546fba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. DNA methylation and hepatic insulin resistance and steatosis. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 2012;15:350–356. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283546f9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nie Y, Ma RC, Chan JC, Xu H, Xu G. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide impairs insulin signaling via inducing adipocyte inflammation in glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide receptor-overexpressing adipocytes. FASEB Journal. 2012;26:2383–2393. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-196782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt SL, Harmon KA, Sharp TA, Kealey EH, Bessesen DH. The effects of overfeeding on spontaneous physical activity in obesity prone and obesity resistant humans. Obesity. 2012;20:2183–2193. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magkos F, Fabbrini E, Conte C, Patterson BW, Klein S. Relationship between adipose tissue lipolytic activity and skeletal muscle insulin resistance in nondiabetic women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97:E1219–E1223. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjorntorp P. The associations between obesity, adipose tissue distribution and disease. Acta Medica Scandinavica. 1988;223(723):121–134. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1987.tb05935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox CS, White CC, Lohman K, et al. Genome-wide association of pericardial fat identifies a unique locus for ectopic fat. PLOS Genetics. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002705.e1002705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lizcano F, Vargas D. EID1-induces brown-like adipocyte traits in white 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2010;398(2):160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morganstein DL, Wu P, Mane MR, Fisk NM, White R, Parker MG. Human fetal mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into brown and white adipocytes: a role for ERRα in human UCP1 expression. Cell Research. 2010;20(4):434–444. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cypess AM, Kahn CR. Brown fat as a therapy for obesity and diabetes. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2010;17(2):143–149. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328337a81f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng Y-H, Kokkotou E, Schulz TJ, et al. New role of bone morphogenetic protein 7 in brown adipogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature. 2008;454(7207):1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/nature07221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cristancho AG, Lazar MA. Forming functional fat: a growing understanding of adipocyte differentiation. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2011;12(11):722–734. doi: 10.1038/nrm3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maenhaut N, van de Voorde J. Regulation of vascular tone by adipocytes. BMC Medicine. 2011;9, article 25 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harwood HJ., Jr. The adipocyte as an endocrine organ in the regulation of metabolic homeostasis. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:57–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Awa WL, Fach E, Krakow D, et al. Type 2 diabetes from pediatric to geriatric age: analysis of gender and obesity among 120 183 patients from the German/Austrian DPV database. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2012;167:245–254. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wietlisbach V, Marques-Vidal P, Kuulasmaa K, Karvanen J, Paccaud F. The relation of body mass index and abdominal adiposity with dyslipidemia in 27 general populations of the WHO MONICA Project. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2013;2(5):432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y. Overweight and obesity in China. British Medical Journal. 2006;333(7564):362–363. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7564.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C. Rising burden of obesity in Asia. Journal of Obesity. 2010;2010:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2010/868573.868573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, et al. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;95(2):297–308. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.024927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clegg DJ. Minireview: the year in review of estrogen regulation of metabolism. Molecular Endocrinology. 2012;26:1957–1960. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carr MC. The emergence of the metabolic syndrome with menopause. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88(6):2404–2411. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mauvais-Jarvis F. Estrogen and androgen receptors: regulators of fuel homeostasis and emerging targets for diabetes and obesity. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;22(1):24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casey PH, Bradley RH, Whiteside-Mansell L, Barrett K, Gossett JM, Simpson PM. Evolution of obesity in a low birth weight cohort. Journal of Perinatology. 2012;32(2):91–96. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis SR, Castelo-Branco C, Chedraui P, et al. Understanding weight gain at menopause. Climacteric. 2012;15:419–429. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2012.707385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heine PA, Taylor JA, Iwamoto GA, Lubahn DB, Cooke PS. Increased adipose tissue in male and female estrogen receptor-α knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(23):12729–12734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murata Y, Robertson KM, Jones MEE, Simpson ER. Effect of estrogen deficiency in the male: the ArKO mouse model. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2002;193(1-2):7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grodstein F, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ. A prospective, observational study of postmenopausal hormone therapy and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;133(12):933–941. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-12-200012190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouchard C, Despres J-P, Mauriege P. Genetic and nongenetic determinants of regional fat distribution. Endocrine Reviews. 1993;14(1):72–93. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-1-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garaulet M, Pérez-Llamas F, Baraza JC, et al. Body fat distribution in pre- and post-menopausal women: metabolic and anthropometric variables. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 2002;6(2):123–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garaulet M, Pérez-Llamas F, Zamora S, Javier Tébar F. Comparative study of the type of obesity in pre- and postmenopausal women: relationship with fat cell data, fatty acid composition and endocrine, metabolic, nutritional and psychological variables. Medicina Clinica. 2002;118(8):281–286. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(02)72361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toth MJ, Poehlman ET, Matthews DE, Tchernof A, MacCoss MJ. Effects of estradiol and progesterone on body composition, protein synthesis, and lipoprotein lipase in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;280(3):E496–E501. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.3.E496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elbers JMH, De Jong S, Teerlink T, Asscheman H, Seidell JC, Gooren LJG. Changes in fat cell size and in vitro lipolytic activity of abdominal and gluteal adipocytes after a one-year cross-sex hormone administration in transsexuals. Metabolism. 1999;48(11):1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elbers JMH, Asscheman H, Seidell JC, Gooren LJG. Effects of sex steroid hormones on regional fat depots as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging in transsexuals. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276(2):E317–E325. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.2.E317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nelson LR, Bulun SE. Estrogen production and action. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2001;45(3):S116–S124. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.117432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen Z, Saloniemi T, Rönnblad A, Järvensivu P, Pakarinen P, Poutanen M. Sex steroid-dependent and -independent action of hydroxysteroid (17β) dehydrogenase 2: evidence from transgenic female mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150(11):4941–4949. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weihua Z, Andersson S, Cheng G, Simpson ER, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Update on estrogen signaling. FEBS Letters. 2003;546(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00436-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banerjee S, Chambliss KL, Mineo C, Shaul PW. Recent insights into non-nuclear actions of estrogen receptor alpha. Steroids. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simons SS, Jr., Edwards DP, Kumar R. Dynamic structures of nuclear hormone receptors: new promises and challenges. Molecular Endocrinology. 2013;28(2):173–182. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barros RPA, Gustafsson J-Å. Estrogen receptors and the metabolic network. Cell Metabolism. 2011;14(3):289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faulds MH, Zhao C, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson J-Å. The diversity of sex steroid action: regulation of metabolism by estrogen signaling. Journal of Endocrinology. 2012;212(1):3–12. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Safe S, Kim K. Non-classical genomic estrogen receptor (ER)/specificity protein and ER/activating protein-1 signaling pathways. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2008;41(5-6):263–275. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Almeida M, Han L, O’Brien CA, Kousteni S, Manolagas SC. Classical genotropic versus kinase-initiated regulation of gene transcription by the estrogen receptor α . Endocrinology. 2006;147(4):1986–1996. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kousteni S, Bellido T, Plotkin LI, et al. Nongenotropic, sex-nonspecific signaling through the estrogen or androgen receptors: dissociation from transcriptional activity. Cell. 2001;104(5):719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levin ER. Cellular functions of the plasma membrane estrogen receptor. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;10(9):374–376. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evinger AJ, III, Levin ER. Requirements for estrogen receptor α membrane localization and function. Steroids. 2005;70(5–7):361–363. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oosthuyse T, Bosch AN. Oestrogen’s regulation of fat metabolism during exercise and gender specific effects. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2012;12:363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mauvais-Jarvis F, Clegg DJ, Hevener AL. The role of estrogens in control of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Endocrine Reviews. 2013;34:309–338. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller WL, Auchus RJ. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocrine Reviews. 2011;32(1):81–151. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weigt C, Hertrampf T, Zoth N, Fritzemeier KH, Diel P. Impact of estradiol, ER subtype specific agonists and genistein on energy homeostasis in a rat model of nutrition induced obesity. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2012;351(2):227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodríguez-Cuenca S, Monjo M, Gianotti M, Proenza AM, Roca P. Expression of mitochondrial biogenesis-signaling factors in brown adipocytes is influenced specifically by 17β-estradiol, testosterone, and progesterone. American Journal of Physiology. 2007;292(1):E340–E346. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00175.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodriguez-Cuenca S, Monjo M, Frontera M, Gianotti M, Proenza AM, Roca P. Sex steroid receptor expression profile in brown adipose tissue. Effects of hormonal status. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2007;20(6):877–886. doi: 10.1159/000110448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park CJ, Zhao Z, Glidewell-Kenney C, et al. Genetic rescue of nonclassical ERα signaling normalizes energy balance in obese Erα-null mutant mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(2):604–612. doi: 10.1172/JCI41702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar R, McEwan IJ. Allosteric modulators of steroid hormone receptors: structural dynamics and gene regulation. Endocrine Reviews. 2012;33:271–299. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu X, Peng L, Lv M, ding K. Recent advance in the design of small molecular modulators of estrogen-related receptors. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2012;18:3421–3431. doi: 10.2174/138161212801227113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Casazza K, Page GP, Fernandez JR. The association between the rs2234693 and rs9340799 estrogen receptor α gene polymorphisms and risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a review. Biological Research for Nursing. 2010;12(1):84–97. doi: 10.1177/1099800410371118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pastorelli R, Carpi D, Airoldi L, et al. Proteome analysis for the identification of in vivo estrogen-regulated proteins in bone. Proteomics. 2005;5(18):4936–4945. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lovejoy JC. The menopause and obesity. Primary Care. 2003;30(2):317–325. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(03)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pedersen SB, Kristensen K, Hermann PA, Katzenellenbogen JA, Richelsen B. Estrogen controls lipolysis by up-regulating α2A-adrenergic receptors directly in human adipose tissue through the estrogen receptor α. Implications for the female fat distribution. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;89(4):1869–1878. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gormsen LC, Host C, Hjerrild BE, et al. Estradiol acutely inhibits whole body lipid oxidation and attenuates lipolysis in subcutaneous adipose tissue: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in postmenopausal women. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2012;167:543–551. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zang H, Rydén M, Wåhlen K, Dahlman-Wright K, Arner P, Hirschberg AL. Effects of testosterone and estrogen treatment on lipolysis signaling pathways in subcutaneous adipose tissue of postmenopausal women. Fertility and Sterility. 2007;88(1):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yonezawa R, Wada T, Matsumoto N, et al. Central versus peripheral impact of estradiol on the impaired glucose metabolism in ovariectomized mice on a high-fat diet. American Journal of Physiology. 2012;303:E445–E456. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00638.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gavin KM, Cooper EE, Raymer DK, Hickner RC. Estradiol effects on subcutaneous adipose tissue lipolysis in premenopausal women are adipose tissue depot specific and treatment dependent. American Journal of Physiology. 2013;304:E1167–E1174. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00023.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Monjo M, Pujol E, Roca P. α2- to β3-adrenoceptor switch in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and adipocytes: modulation by testosterone, 17β-estradiol, and progesterone. American Journal of Physiology. 2005;289(1):E145–E150. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00563.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tessier S, Riesco É, Lacaille M, et al. Impact of walking on adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase activity and expression in pre- and postmenopausal women. Obesity Facts. 2010;3(3):191–199. doi: 10.1159/000314611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jeong S, Yoon M. 17β-Estradiol inhibition of PPARγ-induced adipogenesis and adipocyte-specific gene expression. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2011;32(2):230–238. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abeles EDG, Cordeiro LMDS, Martins ADS, et al. Estrogen therapy attenuates adiposity markers in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Metabolism. 2012;61:1100–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beckett T, Tchernof A, Toth MJ. Effect of ovariectomy and estradiol replacement on skeletal muscle enzyme activity in female rats. Metabolism. 2002;51(11):1397–1401. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.35592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stirone C, Boroujerdi A, Duckles SP, Krause DN. Estrogen receptor activation of phosphoinositide-3 kinase, Akt, and nitric oxide signaling in cerebral blood vessels: rapid and long-term effects. Molecular Pharmacology. 2005;67(1):105–113. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bossy-Wetzel E, Green DR. Apoptosis: checkpoint at the mitochondrial frontier. Mutation Research. 1999;434(3):243–251. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(99)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rogers NH, Witczak CA, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ, Greenberg AS. Estradiol stimulates Akt, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and TBC1D1/4, but not glucose uptake in rat soleus. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;382(4):646–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alaynick WA. Nuclear receptors, mitochondria and lipid metabolism. Mitochondrion. 2008;8(4):329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kalra SP, Dube MG, Pu S, Xu B, Horvath TL, Kalra PS. Interacting appetite-regulating pathways in the hypothalamic regulation of body weight. Endocrine Reviews. 1999;20(1):68–100. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.1.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kostanyan A, Nazaryan K. Rat brain glycolysis regulation by estradiol-17β . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1992;1133(3):301–306. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90051-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim KW, Sohn J-W, Kohno D, Xu Y, Williams K, Elmquist JK. SF-1 in the ventral medial hypothalamic nucleus: a key regulator of homeostasis. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2011;336(1-2):219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S. Genetics of obesity in humans. Endocrine Reviews. 2006;27(7):710–718. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Butera PC. Estradiol and the control of food intake. Physiology and Behavior. 2010;99(2):175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xu Y, Nedungadi TP, Zhu L, et al. Distinct hypothalamic neurons mediate estrogenic effects on energy homeostasis and reproduction. Cell Metabolism. 2011;14(4):453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Obici S. Minireview: molecular targets for obesity therapy in the brain. Endocrinology. 2009;150(6):2512–2517. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hart-Unger S, Korach KS. Estrogens and obesity: is it all in our heads? Cell Metabolism. 2011;14(4):435–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roepke TA. Oestrogen modulates hypothalamic control of energy homeostasis through multiple mechanisms. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2009;21(2):141–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Šlamberová R, Hnatczuk OC, Vathy I. Expression of proopiomelanocortin and proenkephalin mRNA in sexually dimorphic brain regions are altered in adult male and female rats treated prenatally with morphine. Journal of Peptide Research. 2004;63(5):399–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2004.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hill JW, Urban JH, Xu M, Levine JE. Estrogen induces neuropeptide Y (NPY) Y1 receptor gene expression and responsiveness to NPY in gonadotrope-enriched pituitary cell cultures. Endocrinology. 2004;145(5):2283–2290. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.de Souza FSJ, Nasif S, López-Leal R, Levi DH, Low MJ, Rubinsten M. The estrogen receptor α colocalizes with proopiomelanocortin in hypothalamic neurons and binds to a conserved motif present in the neuron-specific enhancer nPE2. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;660(1):181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.10.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402(6762):656–660. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kojima M, Kangawa K. Ghrelin: structure and function. Physiological Reviews. 2005;85(2):495–522. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, et al. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 2001;409(6817):194–198. doi: 10.1038/35051587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dafopoulos K, Chalvatzas N, Kosmas G, Kallitsaris A, Pournaras S, Messinis IE. The effect of estrogens on plasma ghrelin concentrations in women. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2010;33(2):109–112. doi: 10.1007/BF03346563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pillot B, Duraffourd C, Bégeot M, et al. Role of hypothalamic melanocortin system in adaptation of food intake to food protein increase in mice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019107.e19107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Krashes MJ, Koda S, Ye C, et al. Rapid, reversible activation of AgRP neurons drives feeding behavior in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(4):1424–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI46229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Biebermann H, Kühnen P, Kleinau G, Krude H. The neuroendocrine circuitry controlled by POMC, MSH, and AGRP. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 2012;209:47–75. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-24716-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Messina MM, Boersma G, Overton JM, Eckel LA. Estradiol decreases the orexigenic effect of melanin-concentrating hormone in ovariectomized rats. Physiology and Behavior. 2006;88(4-5):523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Santollo J, Eckel LA. The orexigenic effect of melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) is influenced by sex and stage of the estrous cycle. Physiology and Behavior. 2008;93(4-5):842–850. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Horvath TL. Synaptic plasticity in energy balance regulation. Obesity. 2006;14, supplement 5:228S–233S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nahon J-L. The melanocortins and melanin-concentrating hormone in the central regulation of feeding behavior and energy homeostasis. Comptes Rendus Biologies. 2006;329(8):623–638. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Riant E, Waget A, Cogo H, Arnal J-F, Burcelin R, Gourdy P. Estrogens protect against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150(5):2109–2117. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Barros RPA, Gabbi C, Morani A, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Participation of ERα and ERβ in glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue. American Journal of Physiology. 2009;297(1):E124–E133. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00189.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Naaz A, Zakroczymski M, Heine P, et al. Effect of ovariectomy on adipose tissue of mice in the absence of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα): a potential role for estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2002;34(11-12):758–763. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-38259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wajchenberg BL. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocrine Reviews. 2000;21(6):697–738. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.6.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Antonson P, Omoto Y, Humire P, Gustafsson JA. Generation of ERalpha-floxed and knockout mice using the Cre/LoxP system. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2012;424:710–716. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Geary N, Asarian L, Korach KS, Pfaff DW, Ogawa S. Deficits in E2-dependent control of feeding, weight gain, and cholecystokinin satiation in ER-α null mice. Endocrinology. 2001;142(11):4751–4757. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gao Q, Mezei G, Nie Y, et al. Anorectic estrogen mimics leptin’s effect on the rewiring of melanocortin cells and Stat3 signaling in obese animals. Nature Medicine. 2007;13(1):89–94. doi: 10.1038/nm1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yan L, Ge H, Li H, et al. Gender-specific proteomic alterations in glycolytic and mitochondrial pathways in aging monkey hearts. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2004;37(5):921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cheng CM, Cohen M, Wang JIE, Bondy CA. Estrogen augments glucose transporter and IGF1 expression in primate cerebral cortex. FASEB Journal. 2001;15(6):907–915. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0398com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Stirone C, Duckles SP, Krause DN, Procaccio V. Estrogen increases mitochondrial efficiency and reduces oxidative stress in cerebral blood vessels. Molecular Pharmacology. 2005;68(4):959–965. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.014662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Razmara A, Sunday L, Stirone C, et al. Mitochondrial effects of estrogen are mediated by estrogen receptor α in brain endothelial cells. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2008;325(3):782–790. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.134072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Singh Yadav RN. Isocitrate dehydrogenase activity and its regulation by estradiol in tissues of rats of various ages. Cell Biochemistry and Function. 1988;6(3):197–202. doi: 10.1002/cbf.290060308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Amengual-Cladera E, Lladó I, Gianotti M, Proenza AM. Retroperitoneal white adipose tissue mitochondrial function and adiponectin expression in response to ovariectomy and 17β-estradiol replacement. Steroids. 2012;77(6):659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Homma H, Kurachi H, Nishio Y, et al. Estrogen suppresses transcription of lipoprotein lipase gene. Existence of a unique estrogen response element on the lipoprotein lipase promoter. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(15):11404–11411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Leclere R, Torregrosa-Munumer R, Kireev R, et al. Effect of estrogens on base excision repair in brain and liver mitochondria of aged female rats. Biogerontology. 2013;14:383–394. doi: 10.1007/s10522-013-9431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tam CS, Lecoultre V, Ravussin E, et al. Brown adipose tissue: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Circulation. 2012;125:2782–2791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.042929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Nikolic DM, Li Y, Liu S, Wang S. Overexpression of constitutively active PKG-I protects female, but not male mice from diet-induced obesity. Obesity. 2011;19(4):784–791. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Matsushita M, Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Kameya T, Sugie H, Saito M. Impact of brown adipose tissue on body fatness and glucose metabolism in healthy humans. International Journal of Obesity. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pedersen SB, Bruun JM, Kristensen K, Richelsen B. Regulation of UCP1, UCP2, and UCP3 mRNA expression in brown adipose tissue, white adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle in rats by estrogen. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001;288(1):191–197. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Velickovic K, Cvoro A, Srdic B, et al. Expression and subcellular localization of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in human fetal brown adipose tissue. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Strott CA. Steroid sulfotransferases. Endocrine Reviews. 1996;17(6):670–697. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-6-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wada T, Ihunnah CA, Gao J, et al. Estrogen sulfotransferase inhibits adipocyte differentiation. Molecular Endocrinology. 2011;25(9):1612–1623. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mauvais-Jarvis F. Estrogen sulfotransferase: intracrinology meets metabolic diseases. Diabetes. 2012;61:1353–1354. doi: 10.2337/db12-0357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tritos NA, Segal-Lieberman G, Vezeridis PS, Maratos-Flier E. Estradiol-induced anorexia is independent of leptin and melanin-concentrating hormone. Obesity Research. 2004;12(4):716–724. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ladyman SR, Grattan DR. Suppression of leptin receptor mRNA and leptin responsiveness in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus during pregnancy in the rat. Endocrinology. 2005;146(9):3868–3874. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Clegg DJ, Brown LM, Woods SC, Benoit SC. Gonadal hormones determine sensitivity to central leptin and insulin. Diabetes. 2006;55:978–987. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lobo RA. Metabolic syndrome after menopause and the role of hormones. Maturitas. 2008;60(1):10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Combs TP, Pajvani UB, Berg AH, et al. A transgenic mouse with a deletion in the collagenous domain of adiponectin displays elevated circulating adiponectin and improved insulin sensitivity. Endocrinology. 2004;145(1):367–383. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Combs TP, Berg AH, Rajala MW, et al. Sexual differentiation, pregnancy, calorie restriction, and aging affect the adipocyte-specific secretory protein adiponectin. Diabetes. 2003;52(2):268–276. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Rose DP, Komninou D, Stephenson GD. Obesity, adipocytokines, and insulin resistance in breast cancer. Obesity Reviews. 2004;5(3):153–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, et al. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001;409(6818):307–312. doi: 10.1038/35053000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Simpson ER, Misso M, Hewitt KN, et al. Estrogen—the good, the bad, and the unexpected. Endocrine Reviews. 2005;26(3):322–330. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Stubbins RE, Najjar K, Holcomb VB, Hong J, Núñez NP. Oestrogen alters adipocyte biology and protects female mice from adipocyte inflammation and insulin resistance. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2012;14(1):58–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Grün F, Blumberg B. Minireview: the case for obesogens. Molecular Endocrinology. 2009;23(8):1127–1134. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Cagnacci A, Renzi A, Cannoletta M, Pirillo D, Arangino S, Volpe A. Tibolone and estradiol plus norethisterone acetate similarly influence endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in healthy postmenopausal women. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;86(2):480–483. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Meeuwsen IB, Samson MM, Duursma SA, Verhaar HJ. The effect of tibolone on fat mass, fat-free mass, and total body water in postmenopausal women. Endocrinology. 2001;142(11):4813–4817. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Boyanov MA, Shinkov AD. Effects of tibolone on body composition in postmenopausal women: a 1-year follow up study. Maturitas. 2005;51(4):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Lee YM, Choi JS, Kim MH, Jung MH, Lee YS, Song J. Effects of dietary genistein on hepatic lipid metabolism and mitochondrial function in mice fed high-fat diets. Nutrition. 2006;22(9):956–964. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wu J, Oka J, Tabata I, et al. Effects of isoflavone and exercise on BMD and fat mass in postmenopausal Japanese women: a 1-year randomized placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2006;21(5):780–789. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kim H-K, Nelson-Dooley C, Della-Fera MA, et al. Genistein decreases food intake, body weight, and fat pad weight and causes adipose tissue apoptosis in ovariectomized female mice. Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136(2):409–414. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Damcott CM, Sack P, Shuldiner AR. The genetics of obesity. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2003;32(4):761–786. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(03)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Teeguarden JG, Calafat AM, Ye X, et al. Twenty-four hour human urine and serum profiles of bisphenol A during high-dietary exposure. Toxicological Sciences. 2011;123(1):48–57. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Heindel JJ. Role of exposure to environmental chemicals in the developmental basis of disease and dysfunction. Reproductive Toxicology. 2007;23(3):257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Bogacka I, Roane DS, Xi X, et al. Expression levels of genes likely involved in glucose-sensing in the obese Zucker rat brain. Nutritional Neuroscience. 2004;7(2):67–74. doi: 10.1080/10284150410001710401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Rasier G, Parent A-S, Gérard A, Lebrethon M-C, Bourguignon J-P. Early maturation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion and sexual precocity after exposure of infant female rats to estradiol or dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. Biology of Reproduction. 2007;77(4):734–742. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.059303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon J-P, Giudice LC, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocrine Reviews. 2009;30(4):293–342. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Rokutanda N, Iwasaki T, Odawara H, et al. Augmentation of estrogen receptor-mediated transcription by steroid and xenobiotic receptor. Endocrine. 2008;33(3):305–316. doi: 10.1007/s12020-008-9091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Sakurai K, Kawazuma M, Adachi T, et al. Bisphenol A affects glucose transport in mouse 3T3-F442A adipocytes. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;141(2):209–214. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Reiss NA. Ontogeny and estrogen responsiveness of creatine kinase and glycolytic enzymes in brain and uterus of rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1987;84(2):197–202. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Eshtiaghi R, Esteghamati A, Nakhjavani M. Menopause is an independent predictor of metabolic syndrome in Iranian women. Maturitas. 2010;65(3):262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Munoz J, Derstine A, Gower BA. Fat distribution and insulin sensitivity in postmenopausal women: influence of hormone replacement. Obesity Research. 2002;10(6):424–431. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Pickar JH, Thorneycroft I, Whitehead M. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on the endometrium and lipid parameters: a review of randomized clinical trials, 1985 to 1995. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;178(5):1087–1099. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Chmouliovsky L, Habicht F, James RW, Lehmann T, Campana A, Golay A. Beneficial effect of hormone replacement therapy on weight loss in obese menopausal women. Maturitas. 1999;32(3):147–153. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Kenny AM, Kleppinger A, Wang Y, Prestwood KM. Effects of ultra-low-dose estrogen therapy on muscle and physical function in older women. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(11):1973–1977. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Thorneycroft IH, Lindsay R, Pickar JH. Body composition during treatment with conjugated estrogens with and without medroxyprogesterone acetate: analysis of the women’s Health, Osteoporosis, Progestin, Estrogen (HOPE) trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197(2):137.e1–137.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Tankó LB, Movsesyan L, Svendsen OL, Christiansen C. The effect of hormone replacement therapy on appendicular lean tissue mass in early postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2002;9(2):117–121. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Chu MC, Cosper P, Nakhuda GS, Lobo RA. A comparison of oral and transdermal short-term estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women with metabolic syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;86(6):1669–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Salpeter SR, Walsh JME, Ormiston TM, Greyber E, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE. Meta-analysis: effect of hormone-replacement therapy on components of the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2006;8(5):538–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2005.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]