Abstract

Oxidative stress caused by reactive species, including reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species, and unbound, adventitious metal ions (e.g., iron [Fe] and copper [Cu]), is an underlying cause of various neurodegenerative diseases. These reactive species are an inevitable by-product of cellular respiration or other metabolic processes that may cause the oxidation of lipids, nucleic acids, and proteins. Oxidative stress has recently been implicated in depression and anxiety-related disorders. Furthermore, the manifestation of anxiety in numerous psychiatric disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, panic disorder, phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder, highlights the importance of studying the underlying biology of these disorders to gain a better understanding of the disease and to identify common biomarkers for these disorders. Most recently, the expression of glutathione reductase 1 and glyoxalase 1, which are genes involved in antioxidative metabolism, were reported to be correlated with anxiety-related phenotypes. This review focuses on direct and indirect evidence of the potential involvement of oxidative stress in the genesis of anxiety and discusses different opinions that exist in this field. Antioxidant therapeutic strategies are also discussed, highlighting the importance of oxidative stress in the etiology, incidence, progression, and prevention of psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: Antioxidant therapy, anxiety disorders, oxidative stress, toxicity.

1. Oxidative Stress and Reactive Species

1.1. Reactive Oxygen Species

The human brain consumes approximately 20% of basal oxygen during metabolic processes, making the central nervous system very sensitive to oxidative stress [1]. Oxygen metabolism results in the production of oxygen ions and various free radicals. Free radicals are molecules that contain one or more unpaired electrons and are extremely reactive, with life spans of less than 10-11 s. The radicals derived from oxygen represent the most important class of such species generated in living systems and may damage normal cellular compartments, resulting in compromised function. Apart from detrimental effects, ROS have also been shown to be beneficial and play an important role in cell signaling, the induction of mitogenic responses, immune defense mechanisms, cellular senescence, apoptosis, and the breakdown of toxic compounds [2].

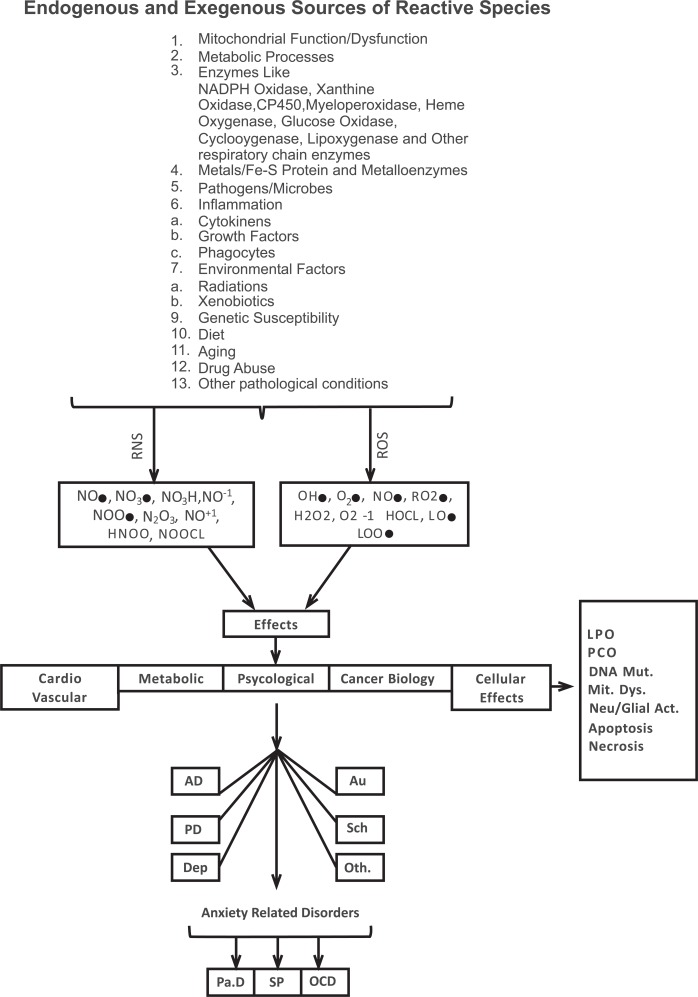

Reactive oxygen species can be produced from both endogenous and exogenous sources (Scheme 1). Endogenous sources include mitochondria, cytochrome P450 metabolism, peroxisomes, and inflammatory cell activation. The literature has shown that isolated mitochondria can generate approximately 2-3 nmol of superoxide per minute per milligram of protein [1]. Other cellular sources of superoxide radical generation include xanthine oxidase (XO), which catalyzes the reaction of hypoxanthine to xanthine and xanthine to uric acid, consequently generating superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide [3]. Neutrophils, eosinophils, and macrophages are other potential sources of cellular reactive species production. The role of cytochrome P450, microsomes, and peroxisomes is also well-documented [4]. Notably, superoxide anions can further interact with other molecules to generate secondary ROS either directly or through enzyme- or metal-catalyzed reactions. Similarly, the auto-oxidation of small molecules, including hemoglobin and myoglobin, mitochondrial components, and oxidative enzymes (e.g., xanthine oxidase (XO), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate [NADP-H+] oxidase], and cyclooxy-genases), and the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids are also reported to produce ROS [5]. Hydroxyl radicals are highly reactive, with a half-life of less than 10-11 s in aqueous solution [6]. They are generated by a variety of mechanisms that involve ionizing radiation that causes the decomposition of H2O2, resulting in the formation of hydrogen atoms (H+) and OH•, further causing significant damage to biomolecules [6].

Scheme. (1).

Free radical production and toxic effects. AD, anxiety disorders; Au, autism; Dep, depression; DNA Mut, DNA mutation; LPO, lipid peroxidation; Mit Dys, mitochondrial dysfunction; Neu/Glia Act, neuronal or glial activation; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; Oth, other disorders; Pa.D, Parkinson’s disease; PCO, protein carbonylation; PD, panic disorder; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Sch, schizophrenia; SP, social phobia.

1.2. Reactive Nitrogen Species

Reactive nitrogen species (RNS) are also generated under normal physiological and pathological conditions (Scheme 1). Nitric oxide (NO•) is abundant, relative to moderately reactive radicals involved in neurotransmission, blood pressure regulation, cellular defense mechanisms, smooth muscle relaxation, and immune regulation processes [7, 8]. The nitric oxide radical (NO) is generated by specific enzymes, such as neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), inducible NOS (iNOS), and endothelial NOS (eNOS) [9]. Nitric oxide is both water- and lipid-soluble and readily diffuses through the cytoplasm and plasma membranes. It can participate in different biochemical processes to damage protein structure and function [10]. Under pathological conditions, such as inflammation, immune cells produce O2− and NO, which react to produce peroxynitrite anions (ONOO−1).

| (1) |

The peroxynitrite anion (ONOO−1) is a potent oxidizing agent that can cause DNA fragmentation and lipid peroxidation and further produce nitrosonium cations (NO+1) and nitroxyl anions (NO−1) [5]. Similarly, NO readily binds certain transition metal ions and may alter normal physiological functions.

| (2) |

1.3. Free Radicals and Metals

The generation of various free radicals is closely linked to the participation of redox-active metals [11, 12], such as iron, copper, manganese, and mercury. Iron regulation has been suggested to ensure that no free intracellular iron exists. Under various conditions, however, such as excess superoxide or reduction in cellular pH, can release “free iron” from iron-containing molecules [12]. The literature has shown that the transferrin protein carries two iron ions, although it is normally only approximately one-third saturated with iron [13]. Transferrin loses its bound iron at acidic pH. The initial 10% of iron in saturated human transferrin is lost at pH 5.4, and the final 10% is lost at pH 4.3 [14]. If transferrin is bound to its receptor, then essentially all of the iron is released at pH 5.6-6.0 [15]. The released Fe [II] can participate in a chain reaction that may include the following Fe2+-mediated basal or autoxidation reactions:

| (3) |

The O2•−1 that is generated can in turn react under acidic conditions to generate hydrogen peroxide and oxygen.

| (4) |

H2O2 and superoxide produced in the above reactions may react through metal catalysis (i.e., a Haber-Weiss reaction) to produce the extremely reactive hydroxyl radical, which may then extract hydrogen atoms from polyunsaturated fatty acids.

| (5) |

| (6) |

Ferrous ion (Fe II ) is the form of iron that is capable of initiating redox reactions with oxygen species. Indeed, the oxidation of Fe [II] to Fe [III] can stimulate ROS production. The possibility that Fe [III] is reduced to Fe [II] through an interaction with O2•−1 during the early phase of lipid peroxidation under acidic conditions, perhaps via an intermediate, perferryl iron [10], cannot be excluded.

| (7) |

| (8) |

In short, the majority of hydroxyl radicals generated in vivo are derived from the metal-catalyzed breakdown of hydrogen peroxide. We can summarize a sample Fenton reaction as the following:

| (9) |

These different and diverse reactions may lead to altered physiological functions and specifically oxidative stress.

2. Oxidative Stress and Psychological Disorders

The nervous system has tremendous reservoirs of polyunsaturated and saturated fatty acids that are extremely susceptible to the escalating effects of oxidative stress. The loss of membrane integrity, protein damage, neuronal dysfunction, lipid and protein oxidation, and DNA damage are some key examples of the consequences of oxidative stress. Antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, reduce molecules or non-enzymatic antioxidants, including vitamin C, vitamin E, carotenoids, thiol antioxidants (e.g., glutathione, thioredoxin, and lipoic acid), natural flavonoids, melatonin (i.e., a hormonal product of the pineal gland), and other compounds [16, 17], constituting a defense mechanism that prevents the escalating effects of ROS. However, when ROS concentrations exceed the antioxidative capacity of an organism, the cells enter a state of oxidative stress, in which excess ROS induces oxidative damage in cellular components.

An excellent review by Andersen in 2004 [18] covered the important topic of whether oxidative stress is a primary cause or mere downstream consequence of the neuro-degenerative process. Whether molecular oxidative damage is involved in emotional neuronal circuitry is still debatable. However, the literature indicates that oxidative stress is or can be associated with different psychological disorders. The depletion of antioxidant enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione reductase (GSR1), non-enzymatic components (e.g., free glutathione), various vitamins (e.g., vitamins A, C, and E), lipid and protein oxidation, DNA damage, and other redox alterations (e.g., selenium depletion and ceruluplasmin alterations) have been reported in various psychological disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, major depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, Parkinson’s disease, autism, and Alzheimer’s disease [19-22]. This review focuses on the possible association between oxidative stress and anxiety.

2.1. Evidence of the Link Between Anxiety and Oxidative Stress

The literature shows a link between anxiety and oxidative stress. Berry et al. [23] showed that pain sensitivity and emotional behavior in wildtype mice increased with age, likely because of the accumulation of oxidative damage. They demonstrated that deletion of the p66Shc gene resulted in lower levels of oxidative stress, reduced pain sensitivity, and reduced anxiety-like behavior in mice. Importantly, the p66Shc gene is responsible for the regulation of reactive species metabolism. Desrumaux et al. [24] showed that vitamin E deficiency resulted in increased levels of central oxidative stress markers that in turn resulted in anxiogenic behavior without abnormalities in locomotor activity in mice. Recent studies have shown the direct involvement of oxidative stress in anxiety-like behavior in rodents [25-29].

Consistent with these findings, Salim et al. [27, 28] suggested the direct involvement of oxidative stress in anxiety-like behavior. Masood et al. [30] found that oxidative stress was induced in the hypothalamus and amygdala by L-buthionine-[S,R]-sulfoximine (BSO), an agent that produces oxidative stress by inhibiting glutathione (GSH) synthesis. These studies concluded that subchronic BSO treatment induced anxiety-like behavior in rats, which was prevented by supplementation with the antioxidant tempol. A linear relationship has also been established between peripheral blood oxidative stress markers and anxiety-like behavior in mice [25]. Rammah et al. [25, 31] used the elevated plus maze, a paradigm that tests anxiety-like behavior in rodents, and found that anxiety-like behavior was positively linked to oxidative status in neuronal and glial cells in the cerebellum and hippocampus, neurons in the cerebral cortex, and peripheral leucocytes (i.e., monocytes, granulocytes, and lymphocytes). Kuloglu et al. [32, 33] highlighted the role of oxidative stress in patients with anxiety disorders. Decreased antioxidant enzyme (i.e., SOD, GPx) levels and consequently higher lipid peroxidation were observed in subjects with obsessive-compulsive disorder and panic disorder. Similarly, Yasunari et al. [34] found a significant association between ROS and anxiety in hypertensive patients. Recent data have also demonstrated a positive correlation between oxidative stress markers and human aging [35] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evidence of Involvement of Oxidative Stress in Anxiety-related Disorders

| S # | Paradigm | Species | Behavioral Profile | Biochemical Profile | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | OF EPM Soc Int |

Mice | Anxiety | p66Shc gene deletion | Berry et al., 2006 |

| 2. | OF | Mice | Anxiety | Plasma phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) effect on vitamin E transport | Desrumeux et al., 2005 |

| 3. | Light/dark test | Mice | Anxiety | Intracellular ROS in peripheral granulocytes | Bouayed et al., 2007 |

| 4. | Light/dark test OF |

Rats | Anxiety | Intragastric vitamin A treatment | Oliveira et al., 2006 |

| 5. | Light/dark test OF |

Rats | Anxiety | L-buthionine-(S,R)-sulfoximine (BSO) | Salim et al., 2010a |

| 6. | Light/dark test OF |

Rats | Anxiety | Urinary 8-isoprostane; malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in the hippocampus and amygdala | Salim et al., 2010b |

| 7. | Light/dark test OF |

Rats | Anxiety | Protein residues of tyrosine and tryptophan in the frontal cortex |

Souza et al., 2007 |

| 8. | EPM OF Hole board test |

Mice | Anxiety | Massod et al., 2008 | |

| 9. | Light/dark test | Mice | Anxiety | ROS in peripheral blood lymphocytes, granulocytes, and monocytes |

Rammal et al., 2008 |

| 10. | DSM-IV criteria | Humans | Obsessive-compulsive disorder | Venous blood levels of GSH-Px, CAT, and MDA antioxidant enzymes | Kuloglu et al., 2002a |

| 11. | DSM-IV criteria | Humans | Panic disorder | Levels of GSH-Px, SOD, CAT, and MDA antioxidant enzymes | Kuloglu et al., 2002b |

| 12. | DSM-IV criteria | Humans | Anxiety | plasma catecholamines and ROS | Yasunari et al., 2006 |

| 13. | EPM | Rats | Anxiety | ROS and MDA in cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum in High and Low Freezing animals | Hassan et al., 2013 |

| 14. | Depression and alcohol use disorders | Animal models (review) |

Depression and alcohol use disorders | ROS levels | Hovatta et al., 2010 |

| 15. | Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and prion disease | Humans (review) | Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and prion disease | ROS and protein aggregation levels | Gaeta and Hider, 2005 |

| 16. | Major depression and bipolar disorder | Humans | Major depression and bipolar disorder | Glo1 mRNA in peripheral white blood cells | Fujimoto et al., 2008 |

| 17. | Depression | Humans | Depression | Copper levels | Salustri et al., 2010 |

| 18. | Alzheimer’s disease | Humans | Alzheimer’s disease | Oxidized purine and pyrimidine basis in nuclear DNA damage | Gabbita et al., 1998 |

| 19. | Aging | Humans and mice (review) | Age-related impairments in learning and memory | ROS effects in LTP of hippocampal cells (review) | Serrano and Klann, 2004 |

| 20. | Mild cognitive impairment | Humans | Mild cognitive impairment | 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal levels in the hippocampus and inferior parietal lobules | Butterfield et al., 2006 |

| 21. | Schizophrenia | Humans | Schizophrenia | Plasma levels of pentosidine and serum vitamin B6 | Arai et al., 2010 |

BSO, L-buthionine-(S,R)-sulfoximine; CAT, catalase; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; EPM, elevated plus maze; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; LTP, long-term potentiation; MDA, malondialdehyde; OF, open field; PLTP, plasma phospholipid transfer protein; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Soc Int, social interaction; SOD, superoxide dismutase

Other studies have reported the involvement of oxidative stress in bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, hypertension, and depression [19, 36-37]. Notably, although human data are more directly applicable and easily interpretable than animal data, the number of patients studied, the lack of standard controls, dietary habits, physical activity, and the possible involvement of other clinical complications may alter the overall redox status of human subjects and must be considered before any definitive conclusions can be drawn.

In 2008, we began a selective breeding program to produce two rat lines, the Carioca high-freezing (CHF) and Carioca low-freezing (CLF) lines, bred for high and low levels of defensive freezing in response to contextual cues previously associated with footshock [38]. The objective was to produce a simple and robust animal model that can be used to explore the underlying mechanisms of anxiety-related disorders. We have shown that contextual fear conditioning is a simple and accurate form of aversive learning [39] that can be used to study the mechanisms involved in pathological anxiety [40]. We obtained persuasive evidence of a clear behavioral (i.e., freezing pattern) divergence between CHF and CLF animals after only three generations [38]. We subsequently characterized these lines by examining different oxidative stress parameters. Reactive oxygen species, thiobarbituric acid reactive substance formation, GPx levels, and CAT activity were measured in different brain structures in the 12th and 16th generations. Consistent with our behavioral data obtained from the 3rd, 7th, and 9th generations, CHF animals showed high levels of oxidative stress, reflected by increased ROS and lipid peroxidation and consequently decreased antioxidant enzymatic levels. Interestingly, we found that the hippocampus was the prime target of the escalating effects of ROS [41].

Our results are in strong agreement with Bonatto et al., Gabbita et al., and Serrano and Klann [42-44], who showed that the hippocampus is affected by the deleterious effects of oxidative stress. These studies are also consistent with a recent report by Allam et al. [45]. Butterfield et al. [46] showed that individuals with mild cognitive impairment exhibited increased lipid peroxidation in the hippocampus and inferior parietal lobule. The hippocampus is an important brain structure involved in contextual fear conditioning. Hippocampal lesions have been shown to disrupt freezing behavior in rats [47, 48]. Increased ROS levels and decreased antioxidant enzyme activity in the hippocampus may be expected to increase neuronal susceptibility and likely disrupt the neural circuitry involved in fear or emotional learning.

Interestingly, we also showed that gross morphological organization of the dentate gyrus, CA1, and CA3 subfields of the hippocampus in CHF rats was not different from control animals [49]. We may conclude that the observed behavioral differences, reflected by differences in freezing response and behavior in the elevated plus maze, between the high and low freezing groups cannot be explained by hippocampal injury. However, one must consider the sensitivity of the optical microscope to detect minute changes in hippocampal neuronal circuitry. Nonetheless, the involvement of hippocampal oxidative stress in CHF animals that may occur at the molecular level may play a causal role in anxiety-related disorders.

2.2. Genetic Evidence of the Association Between Oxidative Stress and Anxiety: Role of Methylglyoxal and Glyoxalase I in Anxiety

The mouse GLO1 gene encodes the 21 kDa, 184-amino-acid enzyme glyoxalase I (GLO1). It is found as a dimer in the cytosol of cells. Its physiological function is to detoxify dicarbonyl metabolites, mostly methylglyoxal (MG), glyoxal and other low-molecular-weight acyclic α-oxoaldehydes. Genetic studies established the possible role of GLO1 in various neuropsychological disorders. Depression [50], schizophrenia [51, 52], panic disorder [53], autism [54, 55], and restless legs syndrome (RLS) [56-59] have been linked to GLO1 expression. This review focuses on the role of GLO1 and MG in anxiety-related disorders (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genetic Evidence of Association of GLO-1 and Anxiety-related Disorders

| Species | Behavioral Assessment | Genes | Reference | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humans | DSM-IV criteria for panic disorder | GLO1 | Politi et al., 2006 | Ala111Glu polymorphism of GLO1 gene |

| Mice | OF Light/dark test |

GLO1 and GSR1 | Hovatta et al., 2005 | — |

| Mice | OF | GLO1 | Benton et al., 2011 | — |

| Mice | EPM | GLO1* | Ditzen et al., 2006 | HAB and LAB mice Red blood cells and amygdaloid expression measures |

| Mice | OF Open-arm exposure test Light/dark test USV test |

GLO1* | Kromer et al., 2005 | HAB and LAB mice |

| Rats and Mice | AVP and GLO1* | Landgraf et al., 2007 | HAB and LAB mice | |

| Mice | OF | GLO1 | Williams et al., 2007 | Inbred, CD1 and wildtype mice were analyzed; whole brain and amygdaloid complex were analyzed |

| Humans | GLO1 | Ranganathan et al., 1999 | — | |

| Rats | OF Light/dark test |

GLO1 and GSR1 | Vollert et al., 2011 | Hippocampus, cortex, and amygdala gene expression analyzed Anxiety-like behavior provoked by sleep deprivation |

AVP, arginine vasopressin; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; EPM, elevated plus maze; HAB, High Anxiety Behavior; LAB, Low Anxiety Behavior; OF, open field; USV, ultrasonic vocalization.

Hovatta et al. [60] identified a close relationship between antioxidative defense mechanisms and anxiety-related phenotypes using genetically inbred [6] “anxious” strains of mice. These investigators found that the expression of the GSR1 gene, which encodes GSR1, and GLO1 is involved in antioxidative metabolism and highly correlated with anxiety-related phenotypes. The expression of these enzymes was higher in the most anxious mice and lower in the less anxious strains. They further confirmed that the overexpression of GLO1 and GSR1 induced by lentiviral vectors in the cingulate cortex increased, whereas the inhibition of GLO1 expression induced by siRNA decreased the level of anxiety-like behavior in mice. Subsequently, Loos et al. [61] conducted a series of studies in which, regardless of genetic correlations, 12 different inbred mouse strains were tested in different behavioral protocols that consisted of home cage behavior, novel cage behavior, the light/dark box, and elevated plus maze. Gene expression data revealed the prominent presence of several important genes, including GLO1 [61]. While more recently, Benton et al. [62] recently measured genetic markers and a diverse range of neurochemical markers (i.e., a total of 36) against the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine across 30 mouse inbred strains. Consistent with the study by Hovatta et al., the authors found that increased GLO1 protein expression corresponded to higher anxiety-like behavior [62].

Interestingly, Hovatta et al., induced the overexpression of the transgenes [glyoxalase 1 and glutathione reductase 1] with a lentiviral vector and not through the direct production of toxic oxygen metabolites, which questions the mechanistic aspects of the work [60]. Similarly, several reports [50, 63-66] contradict the findings of Hovatta et al. [60]. Using outbred Swiss CD1 mice that exhibit high anxiety-related behavior (HAB) or low anxiety-related behavior (LAB), Kromer et al. [64] showed that GLO1 is expressed to a higher extent in LAB mice than in HAB mice in several brain areas, including the hypothalamus, amygdala, and motor cortex. After subjecting the mice to extensive behavioral testing, including the elevated plus maze, dark/light box, open-arm-exposure test, ultrasonic vocalization test, tail suspension test, and forced swim test, and genetic and proteomic analyses, the authors proposed that GLO1 might be a biological marker for trait anxiety. Importantly, the reduced expression of GLO1 was observed not only in brain areas but also in peripheral red blood cells, suggesting that GLO1 expression levels in the brain are highly correlated with those in peripheral blood cells.

Williams et al. [67] suggested that the differences in GLO1 expression in selected lines of mice between some studies [50, 63-66] and Hovatta et al. [60] is most likely attributable to a combination of genetic drift and inbreeding. Genetic variability is likely partially responsible for interspecies and interindividual differences. Thornalley [66] suggested an indirect link between GLO1 expression and oxidative stress. The depletion of GSH in oxidative stress is well known to decrease the in situ activity of GLO1 and increase dicarbonyl glycation. However, this occurs regardless of whether GSH is decreased through an oxidative or non-oxidative mechanism [68]. This author further explained this point by assuming that the formation of MG and MG-H1 are both non-oxidative reactions (i.e., they can proceed in the absence of molecular oxygen). The overexpression of GLO1 decreases dicarbonyl-dependent advanced glycation endproduct (AGE) formation [69], whereas GLO1 inhibition increases AGE formation [70]http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471491406000621 - bib9.

Thornalley [66] suggested that the contradicting studies by Hovatta et al. [60] and Kromer et al. [44] may have had the same neuronal damage induced by MG. However, Hovatta worked with rat strains, and the other studies were conducted with bidirectional lines. Both have different genetic and neuronal vulnerability to different stressful situations and may present differential expression. Nevertheless, one should not neglect the different selection pressures with regard to neuronal damage, differences in the animal models used [71], and the use of HAB mice (i.e., a bidirectional line). Similarly, one strain from Hovatta’s work, FVB/NJ, suffered complex retinal degeneration and visual impairment. Kromer et al. worked with a selective breeding program. Thornalley proposed that high MG exposure/concentration in the anxious strain may have caused higher GLO1 expression. Kromer might have selected a HAB trait that may have initially low GLO1 expression and activity compared with a random population and sustained increases in MG concentrations induced by exposure to normal fluctuations in MG formation. Clinical trials have also demonstrated the reduced expression of GLO1 mRNA in major depression and bipolar disorder during a depressive state [50]. Insulin-responsive element, metal-responsive element, and glucocorticoid-responsive element constitute the promoter region of human GLO1 [72]. Glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) have been shown to be associated with mood disorders, and reduced GR expression has been observed in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala in mood disorder patients [73-75]. However, the precise mechanism of the association between GRs and MG concentration, which may contribute to anxiety, is lacking in the literature.

The findings reported by Eser et al. [76] do not support a relationship between GLO1 expression and anxiety-related behavior. The authors did not find a correlation between GLO1 mRNA expression levels and the severity of cholecystokinin-4 (CCK-4)-induced panic. GLO1 expression levels also did not correlate with state or trait anxiety. Cholecystokinin-4-induced panic attacks are an established and reliable model of human anxiety in healthy volunteers [75, 78-79]. The limitation of this work, however, is that behavioral and cardiovascular panic symptoms elicited by CCK-4 might be different from other anxiety-related phenotypes and cannot be extrapolated to anxious or non-anxious strains or bidirectional lines. Using another approach, Vollert et al. [80] induced oxidative stress by sleep deprivation. The authors observed higher GLO1 and GSR1-1 protein expression levels after acute (24 h) sleep deprivation in the hippocampus, cortex, and amygdala. This effect was most likely an initial antioxidant response to combat the immediate increase in oxidative stress. Importantly, the earlier studies by Salim et al. [27, 28] indicate that the acute induction of oxidative stress by BSO did not cause anxiety-like behavior in rats, whereas the subchronic induction of oxidative stress by BSO or X+XO caused anxiety-like behavior in rats. Later reports from this group suggested that high anxiety corresponds to low GSR1 and GLO1 expression, whereas no anxiety-like behavior is correlated with high levels of GLO1 and GSR1 expression. This certainly suggests some sort of association between GLO1 and GSR1 and anxiety-like behavior in rodents [27, 28].

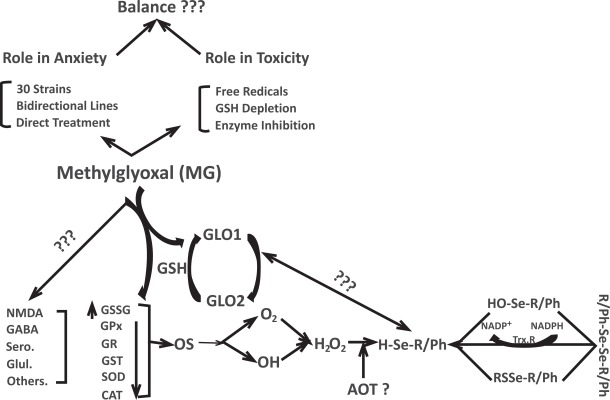

3. Anxiolytic vs toxic effects of methylglyoxal

Hambsch et al. [81] recently reported striking findings in which they showed that MG levels in the brain are negatively correlated with anxiety. Intracerebroventricular injections of MG were given to HAB mice in the 30th generation, inbred normal anxiety-related behavior (NAB) mice in the 4th generation, and CD1 control mice. The administration of MG in inbred HAB mice induced marked anxiolytic-like effects that reached the magnitude of “normal” CD1 controls. These findings suggest that MG concentrations more efficiently modulate anxiety-related behavior than GLO1 expression. These are very interesting observations, and the author attempted to reconcile the discrepancies between different studies concerning GLO1 expression and anxiety-related behavior. Higher GLO1 expression, driven either by virus [60] or multiple copy-number variations [67], might reduce MG concentrations, thus leading to anxiety-like behavior. Increased MG concentrations followed by lower GLO1 expression may generate low anxiety-like behavior. A recent report by Distler showed that treatment with low doses of MG reduced anxiety-like behavior, suggesting an interaction between MG and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors. Their findings indicate that GLO1 increases anxiety by reducing MG concentrations, thereby decreasing GABAA receptor activation. The salient feature of this work is that the authors provided baseline data in which the pharmacological inhibition of GLO1 reduced anxiety, suggesting that GLO1 may be a possible target for the treatment of anxiety-related disorders [82].

Considering the “anxiolytic” role of MG in anxiety or related disorders is interesting, but MG is also well-known to cause various toxic effects. The literature provides some excellent reviews [83] on this topic, which is not the focus of the present review. For simplicity, we can divide the toxic effects of MG into three main classes.

First, extensive data support the hypothesis that MG causes the production of free radicals. The exposure of rat hepatocytes, macrophage-derived cell line U937, rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), mesothelial cells, red blood cells, Jurkat cells, and aortic smooth muscle cells to MG produces escalating levels of free radicals [84-91]. Methylglyoxal-induced ROS production in other cell lines in vitro and the protective effect of the antioxidant NAC further confirm the assumption that oxidative stress may contribute to MG-induced toxicity [92, 93]. Methylglyoxal has been shown to be cytotoxic, possibly involving caspase-independent channeling or the activation of mitochondria in response to oxidative cell injury [94].

Second, considerable data indicate that MG can deplete cellular GSH content. The in vitro treatment of human platelets, rat colonocytes, murine hepatocytes, rat lense, human umbilical veins, endothelial cells, rat VSMCs, spontaneously hypertensive rats, and Wistar-Kyoto rats with 0.5-20 mM MG, with varying incubation times (30 min to 24 h), caused 7-85% GSH depletion compared with controls [95-101]. In vivo treatment with MG from 0.6 mM or 1% MG to 400 mg/kg depleted GSH by 8.0-67% in mouse liver, spleen blood, and embryos with different exposure times [102-106].

Third, MG toxicity may be induced by the inhibition of antioxidant enzymes [107]. Both in vitro and in vivo data have shown that MG exposure inhibits several antioxidant enzymes, such as GSR1, glutathione peroxidase, catalase, SOD, and DT-diaphorase from human, rat, mouse, and bovine tissues, including aortic VSMCs, ADF glioblastoma cells, SH-SY 5Y neuroblastoma cells, and liver, with varying degrees of inhibition that ranged from 10% to nearly 90% with different concentrations of MG (i.e., 200 µM to 100 mM) and incubation times (i.e., 0.5-24 h) [107-112].

One must also consider the possible involvement of different stress-response factors (e.g., c-Jun N-terminal kinase [JNK], nuclear factor-κB [NF-κB], and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors [PPARs]), the expression of which is known to be regulated by cellular redox changes [113-117]. In vitro MG treatment did not activate the NF-κB pathway in SH-SY 5Y cells [118], but contradictory results have also been reported [119]. In contrast, both phosphorylated JNK and PPARα were significantly increased by MG treatment. However, these channels are not activated in other kinds of cells (e.g., ADF cells). The involvement of PPARs in MG-induced cellular stress has also been reported, but its possible role in the signal transduction pathways triggered by MG in models of anxiety are unknown. Interestingly, the cell-line response to activation of various biochemical channels is different. For example, the excessive production of ROS in ADF and SH-SY 5Y cells did not trigger the same biochemical response. The role of MG-induced activation of different stress response factors in animal models of anxiety in either strains or bidirectional lines is unknown and needs to be further explored with regard to the roles of the specific channels involved so that stress-induced exacerbation or initiation can be further decoded (Scheme 2).

Scheme. (2).

Various aspects of MG interactions. AOT, antioxidant therapy; CAT, catalase; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; Glut, glutamate; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GSR, glutathione reductase. GR = glucocorticoid receptor; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; GST, glutathione S-transferase; MG, methylglyoxal; NADP-H, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NADP+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reduced; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; OS, oxidative stress; Sero, serotonin; SOD, superoxide dismutase; Trx-R, thioredoxin reductase.

Another important factor that may play a crucial role in determining the susceptibility of MG-related responses is the GSH-dependent enzymatic system. Treatment with MG has been shown to significantly reduce the concentrations of the GSH-synthesizing enzymes GS and GCS, consequently reducing intracellular GSH content (Scheme 2) [118]. Surprisingly, MG treatment did not alter specific GPx activity, suggesting that this enzyme might not be a molecular target of MG-induced toxicity. The GLO1 enzyme is inhibited by MG, whereas the effect on GLO2 is not significantly different from controls in SH-SY 5Y cells. In ADF cells, MG treatment increased both GLO1 and GLO2 activity. These different results from two different cell lines complicate the mechanisms associated with the GSH-dependent system, worsened by the scarcity of data derived from animal models of anxiety that correlate MG with GSH-dependent enzymatic systems in rat or mice strains or bidirectional lines. Genetic variations in bidirectional lines and strains should be properly addressed because the basal level of antioxidants and detoxifying enzymes and their adaptive response to MG or any ROS might be quite different and differentially contribute to the consequences of oxidative bursts and the genesis of anxiety.

4. Future Directions

4.1. Interaction Between Methylglyoxal and other Neurotransmitter Systems

The involvement of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the mediation of anxiety-related disorders is currently a hot topic in the literature. NMDA receptor antagonists exert anxiolytic effects [120-127]. Thus, considerable evidence indicates that NMDA receptor antagonists that act at numerous sites on the receptor can reduce anxiety. However, the precise locus and neuro-biological mechanism are still being explored. Using genetically modified mice, in which particular receptor subunits are specifically deleted from spatially restricted hippocampal subfields, some authors [128] found the involvement the NR1 and NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor. The present challenge is to identify the MG-induced NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic and cellular mechanisms that could underlie anxiety. This will help us explore the anxiolytic effects of this compound and its possible role in the genesis of anxiety. Dysregulation of the GABA system has been suggested to play an important role in the pathophysiology of panic disorder [129, 130], but the casual role of MG that acts through GABAergic or serotonergic systems in anxious strains or lines has not been demonstrated in the literature, further complicating the relevance and understanding of the association between GLO1 and GSR1 and anxiety. Downregulation of the GABA system in mice has been shown to produce extreme anxiety [131-136]. Similarly, various studies have shown the involvement of serotonin in the development and regulation of anxiety [137, 138]. The modulation of neurotransmitters, such as corticotropin-releasing factor and neurokinin, has also shown an association with anxiety-like behavior [139]. However, few data explain the interaction between MG and these receptor systems in actual anxiety-related models.

4.2. Selective GLO1 Inhibition and Related Aspects

GLO1 is not an obvious participant in signal transduction associated with anxiety-related behavior, which has been demonstrated with ethanol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and neurosteroids [140]. Gingrich recently drew attention for his comment on the possible difference between emotional stress and oxidative stress. He attempted to explain the possible difference between emotional stress and oxidative stress and their involvement in anxiety-related disorders [140]. Although some reports have related GLO1 to the genesis of anxiety, GLO1 and GSR1 are not widely acknowledged for their involvement in anxiety because they are not targets of classic anxiolytic medications. GLO1 inhibition may be considered a novel therapeutic tool for the treatment of anxiety. However, Kim et al. [141] recently suggested that increased GLO1 levels can protect against free radical-induced toxic effects and inhibit the accumulation of oxidative stress and AGR formation in high glucose-fed animal models. The interface between cytotoxic and anxiolytic effects must be established before any future therapeutic interventions are developed. Important to know is whether MG can deplete cellular GSH content, inhibit antioxidant enzymes, or generate free radicals in models of anxiety. This may involve a clearer understanding of the basal expression levels of GLO-I and GLO2, physiological or pathological concentrations of MG, and the cellular adaptive response to ROS.

Similarly, the role of GLO1, related genes, and MG in a diverse range of rat strains and bidirectional lines needs be decoded because these models are bred with different neuronal circuitries. Understanding the precise interaction between GLO1 and MG and different neurotransmitter modulators, anxiolytics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers either in vitro or more preferably in vivo may also be interesting. One must have accurate and sensitive methods to estimate the effects of MG in vivo. A recent review by Nemet et al. covered all of the available literature in this regard [142]. Analyzing other pathological disorders that can lead to increased MG concentrations or other clinical complications that rely on the casual role of MG, such as in diabetes mellitus [143, 144] and Alzheimer’s disease, is also important. Pathological situations that involve protein glycation, the formation of protein deposits (e.g., β-amyloid), and increased protein catabolism are some biochemical examples that can be related to MG. The prevalence of anxiety in conjunction with other clinical complications and specifically the casual role of MG in a broad spectrum of psychological disorders are very important aspects that need to be explored. Palmar et al. recently demonstrated the role of MG in epilepsy and seizures [145]. Another aspect that deserves attention is the precise biochemical mechanism of MG-induced toxicity, ranging from its source of synthesis to the possible cascade that leads to diverse toxic effects. For example, free radicals have been shown to be a key mechanism of MG-induced toxicity. To our knowledge, however, no comprehensive or conclusive proof has been provided that can attribute the evolving toxicity to MG itself. Similarly, exploring other therapeutic interventions may be interesting, such as the following:

1. Inhibition of surplus MG production. For example, AA and Metformin have been shown to prevent the increase in MG in diabetic patients. However, to our knowledge, no studies have directly addressed the inhibition of MG in models of anxiety. Selective GLO1 inhibition may also help in this regard.

2. Increased antioxidant capacity of cells. Antioxidant therapy could be an alternative option to combat anxiety disorders. A diverse range of natural and synthetic antioxidants and neutraceuticals approaches have been described in detail [146, 147], which may help in the design of therapeutics.

With the emerging role of MG and GLO1 in the regulation of anxiety, both top-down and bottom-up strategies need to be developed. The selective inhibition of GLO1 may have beneficial effects by increasing MG concentrations, which can have anxiolytic effects, but an unnecessary increase in MG concentration may trigger toxic effects. Interestingly, the MG detoxification process involves a GLO1 and GLO2 catalytic cycle. The conversion of GLO2 to GLO1 depends on GSH. Methylglyoxal can deplete cellular GSH content and consequently hinder the conversion of GLO2 to GLO1, thus possibly inhibiting GLO1. However, one potential risk is an increase in oxidative burden in the cellular environment; therefore, the potential use of antioxidant therapy cannot be neglected. Interestingly, Masood et al. [30] showed that the anxiolytic diazepam did not ameliorate anxiety induced by BSO treatment. This further complements the fact that oxidative stress could be a factor in anxiety. In fact, treatment with tempol, an antioxidant, reversed the anxious phenotype [27, 28].

4.3. Possible Antioxidant Therapy

The possibility of antioxidant therapy is gaining attention in the literature, and various dietary and synthetic antioxidants have been reported [146-148]. The present review does not focus on antioxidant therapy in paradigms of anxiety, but the literature provides various studies in which natural diet supplements or components protect against anxiety-related disorders. Such antioxidants not only increase the cellular response to oxidative stress but also play an important role in signal transduction [149]. Dietary antioxidants have been reported to possess antidepressant and anxiolytic properties and exert cognitive-enhancing effects. Various natural antioxidants, such as vitamin C, rutin, caffeic acid, and rosmarinic acid, have demonstrated antidepressant activity at relatively low doses (0.1-2 mg/kg) [150].

Polyphenols (e.g., apigenin, rosmarinic acid, chlorogenic acid, and [-]epigallocatechinn gallate), flavonoids (e.g., quercetin [151]), specific foods (e.g., fresh apple [152]), and diets rich in sucrose and honey [153] have been shown to improve antioxidant status and have anxiolytic effects. Similarly, classic antidepressants, such as citalopram, have been shown to exert antioxidant activity in patients with social phobia [150]. Exogenous antioxidants obtained from natural sources may provide an interesting alternative for the treatment of anxiety-related disorders. Vitamin C, lipoic acid, vitamin E, (-carotene, and flavonoids have been shown to exert a direct action against several potent free radicals, such as hydroxyl, lipid peroxide, and super oxide radicals, and other proxidant molecules, such as hydrogen peroxide, thus inhibiting them before they can initiate a chain of oxidative reactions [154]. Various fruits, vegetables, spices, grains, and other natural food products contain important active constituents, such as quercetin, naringin, rutin, cryophyllene, eugenol, hesperetin, casein, vitamin D, oleic acid, (-linolenic acid, curcumin, gingerols, vitamins E, and other minerals. These chemical constituents protect the body against the deleterious effects of reactive species [154]. Mechanistically, antioxidants protect the organism through various diverse pathways that include but are not limited to ROS scavenging, the prevention of excitotoxicity, the dysregulation of metal homeostasis, and the reduction of secondary metabolic burden [155-158]. Closer inspection of Scheme 1 suggests two strategies that can be used to overcome the escalating effects of reactive species. The preferable option might be the upstream approach, in which one can prevent the production of free radicals or inhibit the participation of metals in catalyzing adverse reactions. This is more clinically appropriate than downstream strategies that involve inhibiting free radicals or protecting against these toxic species through the use of antioxidants.

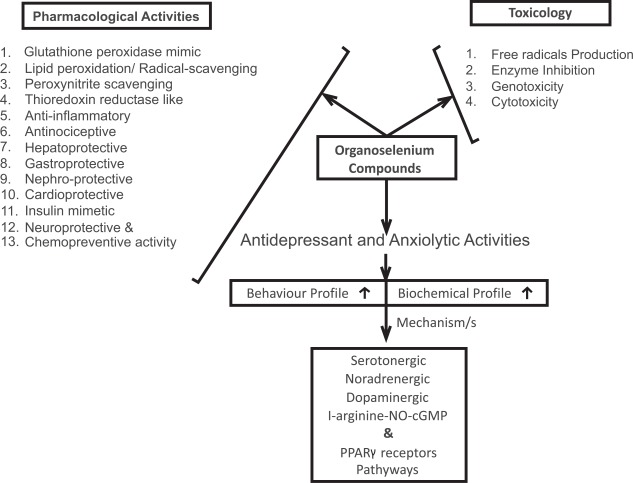

Data on synthetic antioxidants are very diverse, and a range of different classes of compounds have been reported in the literature [148]. However, the interest in selenium chemistry has tremendously increased because of its importance in organic synthesis and biological effects. Various selenium compounds have been shown to have interesting biological effects in different animal and experimental pathological models. Several reviews from our laboratory have focused on this topic [159-161]. Briefly, organoselenium compounds have been shown to possess glutathione peroxidase-mimetic activity [162-166], lipid peroxidation/radical-scavenging/peroxynitrite-scavenging activity [167-171], thioredoxin reductase-like activity [172-176], antiinflammatory and antinociceptive activity [177-181], antinociceptive activity [182-186], hepatoprotective activity [187-191], gastroprotective activity [192-196], nephroprotective activity [197-201], cardioprotective activity [202-206], insulin-mimetic activity [207-211], and neuro-protective activity [212-218] (Scheme 3).

Scheme. (3).

Toxicology and pharmacology of organoselenium compounds. PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ.

In the context of anxiety-related disorders, selenium deficiency has been related to depression, mood disorders, and anxiety [219-221]. Higher selenium intake was shown to improve depressive and anxious symptoms [222, 223]. Organoselenium compounds have been tested in various anxiety-related paradigms. Depending on the chemical structure, route of administration, and dose, various compounds have shown promising antidepressant and anxiolytic activity. Mechanistically, these compounds afford protection through interactions with serotonergic (5-HT1A, 5-HT2A/C, and 5-HT3), noradrenergic (α1 and α2), and dopaminergic (D1, D2, and D3) systems. The role of GABAA receptors, the possible inhibition of the L-arginine-NO-cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathway, and the modulation of PPARγ receptors has been previously reported [224-228] (Table 3). One aspect that deserves attention is the possible toxicity (Scheme 3) of these agents. Although organoselenium compounds offer protection against a wide range of pathological disorders, the toxicity of these compounds cannot be ignored. Free radical generation, the inhibition of thiol-containing enzymes, cytotoxicity, and mutagenicity are some of the key side effects of these compounds [159-161, 229, 230], which should be clearly monitored before any therapeutic intervention is considered.

Table 3.

Anxiolytic Effects of Different Organoselenium Compounds

| Compound | Dose | Route | Species | Behavioral Test | Biochemical Parameters | Involved Mechanism/System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebselen and/or p-Chlorophenylalanine Nan-190 Ketanserin Prazosin Yohimbine Sch23390 Sulpiride |

0-30 mg/kg | Intraperitoneal | Mice | FST TST OF |

ND | Noradrenergic and dopaminergic systems | Posser et al., 2009 |

| Diphenyl diselenide and/or p-chlorophenylalanine methyl ester WAY100635 Ketanserin Ondansetron Haloperidol SCH233390 Sulpiride Prazosin Yohimbine Propranolol |

0.1-30 mg/kg | Oral | Rats | FST OF |

Monoamine oxidase assay | Central monoaminergic system | Savegnago et al., 2007b |

| Diphenyl diselenide and/or Malathion |

50 mg/kg | Oral | Rats | FST OF |

Na+K+ ATPase, acetylcholinesterase, and monoamine oxidase activity TBARS, NPSH, CAT, GPx, GR, and GST activity |

Na+K+ ATPase activity | Acker et al., 2009b |

| Diphenyl diselenide and/or L-arginine methylene blue sildenafil NG-nitro-L-arginine 1H-[1,2,4] oxadiazolo [4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one Fluoxetine Imipramine |

0.1-100 mg/kg | Intracerebroventricular | Mice | FST TST EPM Light/dark box Rotarod |

ND | L-arginine-nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathway | Savegnago et al., 2008b |

| Bis selenide and/or p-chlorophenylalanine methyl ester Ketanserin Ondansetron Prazosin Yohimbine Propranolol SCH23390 Sulpiride, WAY100635 |

0.5-5 mg/kg | Oral | Mice | FST TST |

MAO-A, MAO-B, and Na+ K+ ATPase activity | 5-HT2A/2C and 5-HT3 receptors | Jesse et al., 2010a |

| Bis selenide and/or L-arginine S-nitroso-N-acetyl-penicillamine Sildenafil |

0.5-5 mg/kg | Intracerebroventricular | Mice | FST TST OF |

Nitrate/nitrite content | L-arginine–nitric oxide–cyclic guanosine monophosphate | Jesse et al., 2010b |

| Bis selenide and/or CCl Fluoxetine Amitriptyline Bupropion |

1-5 mg/kg | Oral | Mice | FST OF |

ND | Neuropathic pain model | Jesse et al., 2010c |

| Diphenyl diselenide and/or Bicuculline Ritanserin Ketanserin WAY100635 |

5, 25, and 50 µmol/kg | Intraperitoneal | Rats | OF EPM Footshock avoidance task |

ND | GABAA and 5-HT receptors | Ghisleni et al., 2008a |

| Diphenyl diselenide |

1, 10, and 50 mg/kg | Oral | Male chicks | Vocalizations, jumps, active wakefulness, time standing / sitting motionless with eyes open or closed |

ND | Possibly GABA system | Prigol et al., 2011 |

| Diphenyl diselenide | 25 mg/kg | Maternal subcutaneous injection | 28-day-old pups | EPM OF Rotarod |

Selenium brain status |

Selenium-induced changes | Favero et al., 2006 |

| Diphenyl diselenide and/or Paroxetine Pargyline WAY100635 Ritanserin Ondansetron |

Mice | OF TST FST |

MAO-A and MAO-B activity | 5-HT2A/2C and 5-HT3 receptors | da Rocha et al., 2012 |

||

|

p-chloro-diphenyl diselenide and/or WAY100635 Ritanserin Ondansetron |

10 and 25 mg/kg | Oral | Rats | Ambulation, memory, and depression FST OF |

Na+K+ ATPase activity and ROS levels | 5-HT1A and 5-HT3 receptors | Bortolatto et al., 2012 |

|

m-trifluoromethyl-diphenyl diselenide and/or WAY100635 Ritanserin Ondansetron Naloxone |

50 and 100 mg/kg | Oral | Mice | FST OF |

ND | Serotonergic and opioid systems | BrÜning et al., 2011 |

| Diphenyl diselenide and/or Etraethylammonium Glibenclamide Charybdotoxin Apamin Cromakalim Minoxidil GW 9662 |

1-5 mg/kg | Intracerebroventricular |

Mice | OFT TST |

K+ channels and PPARγ receptors | K+ channels and PPARg receptors | Wilhelm et al., 2010 |

AChE, acetylcholinesterase; CAT, catalase; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; EPM, elevated plus maze; FST, forced swim test; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GR, glucocorticoid receptor GSR; glutathione reductase; GST, glutathione S-transferase; MAO, monoamine oxidase; NPSH, non-protein thiol content; OF, open field; TBARS, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; TST, tail suspension test.

5. Conclusion

Whether oxidative stress is the cause or consequence of anxiety is still an open discussion, but the oxidative stress hypothesis of anxiety has been widely proposed. Genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, and related tools will provide diagnostic insights to help guide research to develop novel pharmacological interventions. Specifically, genetic models and animal models of anxiety using bidirectional lines provide baseline data to understand the potential molecular mechanisms associated with or directly involved in anxiety-related disorders. However, investigations of the neurobiology of anxiety at the molecular level, from neurotransmitter systems to activation of intracellular pathways that trigger anxious behavior, in these animal models are still very limited. Although suggesting antioxidant therapy for anxiety disorders in humans may be premature, reports in the literature suggest a preventive role of antioxidants in this regard. The combined use of antioxidants and classic anxiolytics may be promising. However, more intensive research using animal models of anxiety to investigate toxicological effects, dose formulations, treatment regimens, and synergistic effects between anxiolytics and antioxidants should be conducted before therapeutic applications can be considered an appropriate intervention in human anxiety disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTs

Declared none.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author(s) confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- XO

= Xanthine oxidase

- nadp-h+

= Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase

- nNOS

= Neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- iNOS

= Inducible NOS

- eNOS

= Endothelial NOS

- oNOO−1

= Peroxynitrite Anion

- NO+1

= Nitrosonium Cations

- NO−1

= Nitroxyl Anions

- SOD

= Superoxide Dismutase

- GSR1

= Glutathione Reductase

- BSO

= L-Buthionine- s,r -Sulfoximine

- CHF

= Carioca high-freezing

- CLF

= Carioca low-freezing CA1, and CA3

- GLO1

= Glyoxalase i

- MG

= Methylglyoxal

- HAB

= High anxiety-related behavior

- LAB

= Low anxiety-related behavior

- GRS

= Glucocorticoid Receptors

- CCK-4

= Cholecystokinin-4

- NAB

= Normal anxiety-related behavior

- GABA

= γ-aminobutyric Acid

- GSH

= Glutathione

- JNK

= Jun n-Terminal Kinase

- Nf-κb

= Nuclear factor-κb

- pPARS

= Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors

- GS

= Glutathione Synthase

- AGE

= Advanced Glycation End Product

- GPx

= Glutathione Peroxidase

- TBARS

= Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances

- VSMC

= Vascular Smooth Cells

REFERENCES

- 1.Inoue M, Sato EF, Nishikawa M, Park AM, Kira Y, Imada I, Utsumi K. Mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species and its role in aerobic life. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:2495–2505. doi: 10.2174/0929867033456477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergendi L, Benes L, Duracková Z, Ferencik M. Chemistry physiology and pathology of free radicals. Life Sci. 1999;65:1865–1874. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valko M, Izakovic M, Mazur M, Rhodes CJ, Telser J. Role of oxygen radicals in DNA damage and cancer incidence. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004;266:37–56. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000049134.69131.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta M, Dobashi K, Greene EL, Orak JK, Singh I. Studies on hepatic injury and antioxidant enzyme activities in rat subcellular organelles following in vivo ischemia and reperfusion. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1997;176:337–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamler JS, Simon DI, Osborne JA, Mullins ME, Jaraki O, Michel T, Singel DJ, Loscalzo J. S-nitrosylation of proteins with nitric oxide: synthesis and characterization of biologically active compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:444–448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pastor N, Weinstein H, Jamison E, Brenowitz M. Detailed interpretation of OH radical footprints in a TBP-DNA complex reveals the role of dynamics in the mechanism of sequence-specific binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;304:55–68. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archer S. Measurement of nitric oxide in biological models. FASEB J. 1993;7:349–360. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.2.8440411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem. J. 2001;357:593–615. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghafourifar P, Cadenas E. Mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;26:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ridnour LA, Thomas DD, Mancardi D, Miranda KM, Paolocci N, Feelisch M, Fukuto J, Wink DA. The chemistry of nitrosative stress induced by nitric oxide and reactive nitrogen oxide species: putting perspective on stressful biological situations. Biol. Chem. 2004;385:10. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valko M, Morris H, Cronin MTD. Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005;12:1161–1208. doi: 10.2174/0929867053764635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farina M, Avila DS, da Rocha JB, Aschner M. Metals, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: a focus on iron, manganese and mercury. Neurochem. Int. . 2013;62:575–594. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welch S. A comparison of the structure and properties of serum transferrin from 17 animal species. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 1990;97:417–427. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(90)90138-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sipe DM, Murphy RF. Binding to cellular receptors results in increased iron release from transferrin at mildly acidic pH. J. Biol.hem. . 1991;266:8002–8007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pederson TC, Buege JA, Aust SD. Microsomal electron transport: the role of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-cytochrome c reductase in liver microsomal lipid peroxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248:7134–7141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matés JM, Pérez-Gómez C, Núñez de Castro IN. Antioxidant enzymes and human diseases. Clin. Biochem. 1999;32:595–603. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(99)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCall MR, Frei B. Can antioxidant vitamins materially reduce oxidative damage in humans?. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;26:1034–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen JK. Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: cause or consequence?. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:S18–S25. doi: 10.1038/nrn1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean OM, van den Buuse M, Bush AI, Copolov DL, Ng F, Dodd S, Berk M. A role for glutathione in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia?.Animal models and relevance to clinical practice. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009;16:2965–2976. doi: 10.2174/092986709788803060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu CF, Yu LF, Lin CH, Lin SC. Effect of auricular pellet acupressure on antioxidative systems in high-risk diabetes mellitus. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2008;14:303–307. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hovatta I, Juhila J, Donner J. Oxidative stress in anxiety and comorbid disorders. Neurosci. Res. 2010;68:261–275. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaeta A, Hider RC. The crucial role of metal ions in neuro- degeneration: the basis for a promising therapeutic strategy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005;146:1041–1059. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry A, Capone F, Giorgio M, Pelicci PG, de Kloet ER, Alleva E, Minghetti L, Cirulli F. Deletion of the life span determinant p66Shc prevents age-dependent increases in emotionality and pain sensitivity in mice. Exp. Gerontol. 2007;42:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desrumaux C, Risold PY, Schroeder H, Deckert V, Masson D, Athias A, Laplanche H, Le Guern N, Blache D, Jiang XC, Tall AR, Desor D, Lagrost L. Phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) deficiency reduces brain vitamin E content and increases anxiety in mice. FASEB J. 2005;19:296–297. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2400fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouayed J, Rammal H, Younos C, Soulimani R. Positive correlation between peripheral blood granulocyte oxidative status and level of anxiety In mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007;564:146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Oliveira MR, Silvestrin RB, Mello e Souza T, Moreira JC. Oxidative stress in the hippocampus, anxiety-like behavior and decreased locomotory and exploratory activity of adult rats: effects of sub acute vitamin A supplementation at therapeutic doses. Neurotoxicology. 2007;6:1191–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salim S, Sarraj N, Taneja M, Saha K, Tejada-Simon MV, Chugh G. Moderate treadmill exercise prevents oxidative stress-induced anxiety-like behavior in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2010;208:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salim S, Asghar M, Chugh G, Taneja M, Xia Z, Saha K. Oxidative stress: a potential recipe for anxiety, hypertension and insulin resistance. Brain Res. 2010;1359:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Souza CG, Moreira JD, Siqueira IR, Pereira AG, Rieger DK, Souza DO, Souza TM, Portela LV, Perry ML. Highly palatable diet consumption increases protein oxidation in rat frontal cortex and anxiety-like behavior. Life Sci. 2007;81:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masood A, Nadeem A, Mustafa SJ, O’Donnell JM. Reversal of oxidative stress-induced anxiety by inhibition of phosphodiesterase-2 in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;326:369–379. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rammal H, Bouayed J, Younos C, Soulimani R. The impact of high anxiety levels on the oxidative status of mouse peripheral blood lymphocytes, granulocytes and monocytes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;589:173–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuloglu M, Atmaca M, Tezcan E, Gecici O, Tunckol H, Ustundag B. Antioxidant enzyme activities and malondialdehyde levels in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuro- psychobiology. 2002;46:27–32. doi: 10.1159/000063573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuloglu M, Atmaca M, Tezcan E, Gecici O, Ustundag B, Bulut S. Antioxidant enzyme and malondialdehyde levels in patients with panic disorder. Neuropsychobiology. 2002;46:186–189. doi: 10.1159/000067810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yasunari K, Matsui T, Maeda K, Nakamura M, Watanabe T, Kiriike N. Anxiety-induced plasma norepinephrine augmentation increases reactive oxygen species formation by monocytes in essential hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2006;19:573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pandey KB, Rizvi SI. Markers of oxidative stress in erythrocytes and plasma during aging in humans. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2010;3:2–12. doi: 10.4161/oxim.3.1.10476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ko SH, Cao W, Liu Z. Hypertension management and micro- vascular insulin resistance in diabetes. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2010;12:243–251. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salustri C, Squitti R, Zappasodi F, Ventriglia M, Bevacqua MG, Fontana M, Tecchio F. Oxidative stress and brain glutamate-mediated excitability in depressed patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2010;127:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castro-Gomes V, Landeira-Fernandez J. Amygdaloid lesions produced similar contextual fear conditioning disruption in the Carioca high- and low-conditioned freezing rats. Brain Res. 2008;1233:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Landeira-Fernandez J. Context and Pavlovian conditioning. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1996;29:149–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavlov I, editor. London: Oxford University Press; 1927. Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hassan W, Gomes VC, Pinton S, Rocha JBT, Landeira-Fernandez J. Association between oxidative stress and contextual fear conditioning in Carioca high- and low-conditioned freezing rats. Brain Res. 2013;in press doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonatto F, Polydoro M, Andrades ME, Frota MLC, Jr., Dal-Pizzol F, Rotta LN, Souza DO, Perry ML, Moreira JC. Effect of protein malnutrition on redox state of the hippocampus of rat. Brain Res. 2005;1042:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gabbita SP, Lovell MA, Markesbery WR. Increased nuclear DNA oxidation in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 1998;71:2034–2040. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71052034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serrano F, Klann E. Reactive oxygen species and synaptic plasticity in the aging hippocampus. Ageing Res. Rev. 2004;3:431–443. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allam F, Dao AT, Chugh G, Bohat R, Jafri F, Patki G, Mowrey C, Asghar M, Alkadhi KA, Salim S. Grape powder supplementation prevents oxidative stress-induced anxiety-like behavior, memory impairment, and high blood pressure in rats. J. Nutr. . 2013;in press doi: 10.3945/jn.113.174649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Butterfield DA, Reed T, Perluigi M, De Marco C, Coccia R, Cini C, Sultana R. Elevated protein-bound levels of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, in brain from persons with mild cognitive impairment. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;397:170–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rogers JL, Hunsaker MR, Kesner RP. Effects of ventral and dorsal CA1 subregional lesions on trace fear conditioning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2006;86:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoon T, Otto T. ifferential contributions of dorsal vs.ventral hippocampus to auditory trace fear conditioning. . Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2007;87:464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dias GP, Bevilaqua MC, Silveira AC, Landeira-Fernandez J, Gardino PF. Behavioral profile and dorsal hippocampal cells in Carioca high-conditioned freezing rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2009;205:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujimoto M, Uchida S, Watanuki T, Wakabayashi Y, Otsuki K, Matsubara T, Suetsugi M, Funato H, Watanabe Y. Reduced expression of glyoxalase-1 mRNA in mood disorder patients. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;438:196–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arai M, Yuzawa H, Nohara I, Ohnishi T, Obata N, Iwayama Y, Haga S, Toyota T, Ujike H, Arai M, Ichikawa T, Nishida A, Tanaka Y, Furukawa A, Aikawa Y, Kuroda O, Niizato K, Izawa R, Nakamura K, Mori N, Matsuzawa D, Hashimoto K, Iyo M, Sora I, Matsushita M, Okazaki Y, Yoshikawa T, Miyata T, Itokawa M. Enhanced carbonyl stress in a subpopulation of schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67:589–597. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toyosima M, Maekawa M, Toyota T, Iwayama Y, Arai M, Ichikawa T, Miyashita M, Arinami T, Itokawa M, Yoshikawa T. Schizophrenia with the 22q11.2 deletion and additional genetic defects: case history. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2010;199:245–246. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Politi P, Minoretti P, Falcone C, Martinelli V, Emanuele E. Association analysis of the functional Ala111Glu polymorphism of the glyoxalase I gene in panic disorder. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;396:163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Junaid MA, Kowal D, Barua M, Pullarkat PS, Sklower Brooks S, Pullarkat RK. Proteomic studies identified a single nucleotide polymorphism in glyoxalase I as autism susceptibility factor. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2004;131:11–17. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barua M, Jenkins EC, Chen W, Kuizon S, Pullarkat RK, Junaid MA. Glyoxalase I polymorphism rs2736654 causing the Ala111Glu substitution modulates enzyme activity: implications for autism. Autism Res. 2011;4:262–270. doi: 10.1002/aur.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stefansson H, Rye DB, Hicks A, Petursson H, Ingason A, Thorgeirsson TE, Palsson S, Sigmundsson T, Sigurdsson AP, Eiriksdottir I, Soebech E, Bliwise D, Beck JM, Rosen A, Waddy S, Trotti LM, Iranzo A, Thambisetty M, Hardarson GA, Kristjansson K, Gudmundsson LJ, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Gulcher JR, Gudbjartsson D, Stefansson K. A genetic risk factor for periodic limb movements in sleep. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:639–647. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winkelmann J, Schormair B, Lichtner P, Ripke S, Xiong L, Jalilzadeh S, Fulda S, Pütz B, Eckstein G, Hauk S, Trenkwalder C, Zimprich A, Stiasny-Kolster K, Oertel W, Bachmann CG, Paulus W, Peglau I, Eisensehr I, Montplaisir J, Turecki G, Rouleau G, Gieger C, Illig T, Wichmann HE, Holsboer F, Müller-Myhsok B, Meitinger T. Genome-wide association study of restless legs syndrome identifies common variants in three genomic regions. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1000–1006. doi: 10.1038/ng2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winkelmann J, Czamara D, Schormair B, Knauf F, Schulte EC, Trenkwalder C, Dauvilliers Y, Polo O, Högl B, Berger K, Fuhs A, Gross N, Stiasny-Kolster K, Oertel W, Bachmann CG, Paulus W, Xiong L, Montplaisir J, Rouleau GA, Fietze I, Vávrová J, Kemlink D, Sonka K, Nevsimalova S, Lin SC, Wszolek Z, Vilariño-Güell C, Farrer MJ, Gschliesser V, Frauscher B, Falkenstetter T, Poewe W, Allen RP, Earley CJ, Ondo WG, Le WD, Spieler D, Kaffe M, Zimprich A, Kettunen J, Perola M, Silander K, Cournu-Rebeix I, Francavilla M, Fontenille C, Fontaine B, Vodicka P, Prokisch H, Lichtner P, Peppard P, Faraco J, Mignot E, Gieger C, Illig T, Wichmann HE, Müller-Myhsok B, Meitinger T. Genome-wide association study identifies novel restless legs syndrome susceptibility loci on 2p14 and 16q12. PLoS Genet. 2007;7:e1002171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kemlink D, Polo O, Frauscher B, Gschliesser V, Hogl B, Poewe W, Vodicka P, Vavrova J, Sonka K, Nevsimalova S, Schormair B, Lichtner P, Silander K, Peltonen L, Gieger C, Wichmann HE, Zimprich A, Roeske D, Müller-Myhsok B, Meitinger T, Winkelmann J. Replication of restless legs syndrome loci in three European populations. J. Med. Genet. 2009;46:315–318. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.062992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hovatta I, Tennant RS, Helton R, Marr RA, Singer O, Redwine JM, Ellison JA, Schadt EE, Verma IM, Lockhart DJ, Barlow C. Glyoxalase 1 and glutathione reductase 1 regulate anxiety in mice. Nature. 2005;438:662–666. doi: 10.1038/nature04250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Loos M, Van der Sluis S, Bochdanovits Z, van Zutphen IJ, Pattij T, Stiedl O. Activity and impulsive action are controlled by different genetic and environmental factors. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:817–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benton CS, Miller BH, Skwerer S, Suzuki O, Schultz LE, Cameron MD, Marron JS, Pletcher MT, Wiltshire T. Evaluating genetic markers and neurobiochemical analytes for fluoxetine response using a panel of mouse inbred strains. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2012;221:297–315. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2574-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ditzen C, Jastorff AM, Ke?ler MS, Bunck M, Teplytska L, Erhardt A, Krömer SA, Varadarajulu J, Targosz BS, Sayan-Ayata EF, Holsboer F, Landgraf R, Turck CW. Protein biomarkers in a mouse model of extremes in trait anxiety. Mol. Cell. Proteomic. 2006;5:1914–1920. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600088-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krömer SA, Ke?ler MS, Milfay D, Birg IN, Bunck M, Czibere L, Panhuysen M, Pütz B, Deussing JM, Holsboer F, Landgraf R, Turck CW. Identification of glyoxalase-I as a protein marker in a mouse model of extremes in trait anxiety. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:4375–4384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0115-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Landgraf R, Kessler MS, Bunck M, Murgatroyd C, Spengler D, Zimbelmann M, Nussbaumer M, Czibere L, Turck CW, Singewald N, Rujescu D, Frank E. Candidate genes of anxiety-related behavior in HAB/LAB rats and mice: focus on vasopressin and glyoxalase-I. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2007;31:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thornalley PJ. Unease on the role of glyoxalase 1 in high-anxiety-related behaviour. Trends. Mol. Med. 2006;12:195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams R, 4th; Lim JE, Harr B, Wing C, Walters R, Distler MG, Teschke M, Wu C, Wiltshire T, Su AI, Sokoloff G, Tarantino LM, Borevitz JO, Palmer AA. A common and unstable copy number variant is associated with differences in GLO1 expression and anxiety-like behavior. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abordo EA, Minhas HS, Thornalley PJ. Accumulation of ?-oxoaldehydes during oxidative stress: a role in cytotoxicity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;58:641–648. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shinohara M, Thornalley PJ, Giardino I, Beisswenger P, Thorpe SR, Onorato J, Brownlee M. Overexpression of glyoxalase I in bovine endothelial cells inhibits intracellular advanced glycation endproduct formation and prevents hyperglycaemia-induced increases in macromolecular endocytosis. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1142–1147. doi: 10.1172/JCI119885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thornalley PJ. Antitumour activity of S-p-bromoben- zylglutathione cyclopentyl diester in vitro and in vivo: inhibition of glyoxalase I and induction of apoptosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1996;51:1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cryan JF, Holmes A. The ascent of mouse: advances in modelling human depression and anxiety. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:775–790. doi: 10.1038/nrd1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ranganathan S, Ciaccio PJ, Walsh ES, Tew KD. Genomic sequence of human glyoxalase-I: analysis of promoter activity and its regulation. Gene. 1999;240:149–155. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Knable MB, Barci BM, Webster MJ, Meador-Woodruff J, Torrey EF. Molecular abnormalities of the hippocampus in severe psychiatric illness: postmortem findings from the Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. Mol. Psychiatry. 2004;9:609–620. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perlman WR, Webster MJ, Kleinman JE, Weickert CS. Reduced glucocorticoid and estrogen receptor alpha messenger ribonucleic acid levels in the amygdala of patients with major mental illness. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004;56:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Webster MJ, Knable MB, O’Grady J, Orthmann J, Weickert CS. Regional specificity of brain glucocorticoid receptor mRNA alterations in subjects with schizophrenia and mood disorders. Mol. Psychiatry. 2002;7:985–994. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eser D, Uhr M, Leicht G, Asmus M, Länger A, Schüle C, Baghai TC, Mulert C, Rupprecht R. Glyoxalase-I mRNA expression and CCK-4 induced panic attacks. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011;45:60–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bradwejn J, Koszycki D. Cholecystokinin and panic disorder: past and future clinical research strategies. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. Suppl. 2001;234:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eser D, Schule C, Baghai T, Floesser A, Krebs-Brown A, Enunwa M, de la Motte S, Engel R, Kucher K, Rupprecht R. Evaluation of the CCK-4 model as a challenge paradigm in a population of healthy volunteers within a proof-of-concept study. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2007;192:479–487. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0738-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rupprecht R, Rammes G, Eser D, Baghai TC, Schüle C, Nothdurfter C, Troxler T, Gentsch C, Kalkman HO, Chaperon F, Uzunov V, McAllister KH, Bertaina-Anglade V, La Rochelle CD, Tuerck D, Floesser A, Kiese B, Schumacher M, Landgraf R, Holsboer F, Kucher K. Translocator protein (18 kD) as target for anxiolytics without benzodiazepine-like side effects. Science. 2009;325:1072. doi: 10.1126/science.1175055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vollert C, Zagaar M, Hovatta I, Taneja M, Vu A, Dao A, Levine A, Alkadhi K, Salim S. Exercise prevents sleep deprivation-associated anxiety-like behavior in rats: potential role of oxidative stress mechanisms. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;224:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hambsch B, Chen BG, Brenndörfer J, Meyer M, Avrabos C, Maccarrone G, Liu RH, Eder M, Turck CW, Landgraf R. Methylglyoxal-mediated anxiolysis involves increased protein modification and elevated expression of glyoxalase 1 in the brain. J. Neurochem. . 2010;113:1240–1251. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Distler MG, Plant LD, Sokoloff G, Hawk AJ, Aneas I, Wuenschell GE, Termini J, Meredith SC, Nobrega MA, Palmer AA. Glyoxalase 1 increases anxiety by reducing GABAA receptor agonist methylglyoxal. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:2306–2315. doi: 10.1172/JCI61319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kalapos MP. Methylglyoxal in living organisms: chemistry, biochemistry, toxicology and biological implications. Toxicol. Lett. 1999;110:145–175. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kalapos MP, Littauer A, de Groot H. Has reactive oxygen a role in methylglyoxal toxicity?.A study on cultured rat hepatocytes. . Arch. Toxicol. 1993;67:369–372. doi: 10.1007/BF01973710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]